Scientists are the most trusted source of information for climate change in some of the largest global-south countries, ranking above newspapers, friends and social media.

This is according to a survey of 8,400 people across Chile, Colombia, India, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Vietnam, the results of which have been published in Nature Climate Change.

The study finds that trusting and paying attention to climate scientists was associated with increased climate knowledge, roughly twice the effect size associated with a college degree.

One scientist who was not involved in the research says the findings suggest there is an opportunity to “bolster climate knowledge” in the global south by widening access to climate science information.

When asked to rank how important climate change is for their country, participants rated the issue as high, with the average score for each country above 4.4.

However, when asked to rank the importance of climate change compared to other key social issues, respondents – on average – ranked taking action on climate change ninth out of 13, after improving healthcare, decreasing corruption and increasing employment.

Another expert not involved in the study says the results highlight a “crucial tension” between “strong” public concern about climate change and the perception that other social issues should take priority when allocating “scarce” public resources.

Global-south focus

The impacts of climate change are disproportionately felt by the poorest members of society, who often live in the global south.

Nevertheless, Dr Luis Sebastian Contreras Huerta – a researcher in experimental psychology at Chile’s Universidad Adolfo Ibanez – tells Carbon Brief that research on climate attitudes has been “heavily biased” toward the global north.

Voices from the global south are “often invisible in science”, he adds.

Huerta was not involved in the study, but has published research using surveys to assess public beliefs about climate change. He describes the new study – which is evenly distributed across Chile, Colombia, India, Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa and Vietnam – as “a valuable attempt to capture public views across Latin America, Africa and Asia”.

The seven countries featured in the research include six of the 20 largest in the global south and range from “the lower end of low-to-middle-income countries (Nigeria) to the low end of high-income countries (Chile)”, according to the study.

The survey was administered online by polling company YouGov between April and May 2023. Respondents could answer in English or in other “country-specific languages”. For example, respondents in Chile and Colombia had the option to carry out the survey in Spanish, while those in India could answer in Hindi.

Trust and attention

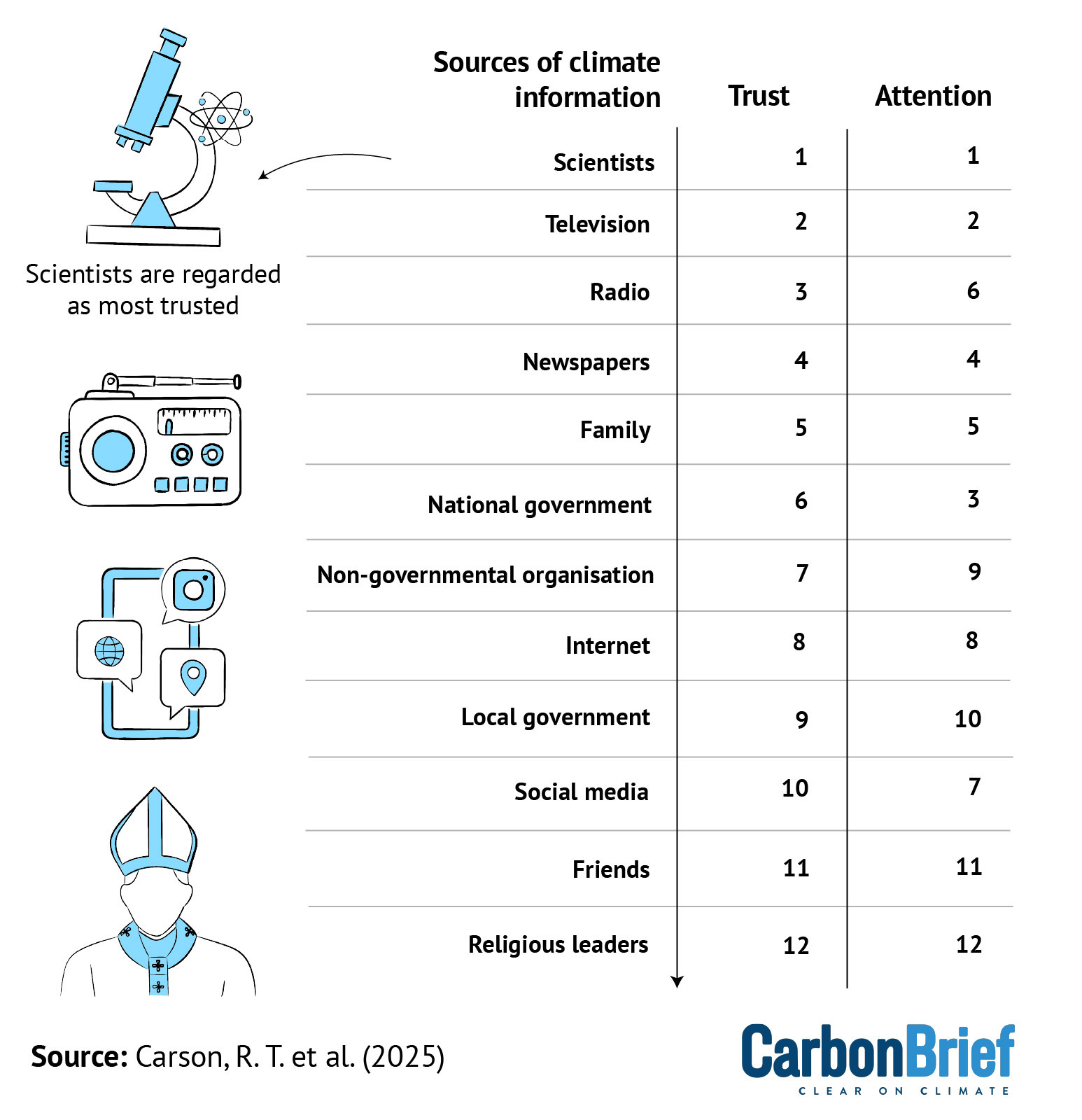

The authors asked survey respondents to rank 12 different sources of information about climate change, based on the attention they pay it and how much they trust it.

The average rankings are shown in the table below, where one indicates the highest level of attention or trust and 12 indicates the lowest.

The table shows that, on average, scientists are ranked the highest for both trust and attention.

The country-specific results show that scientists rank the highest in trust in every country except Vietnam, where they rank second highest after television programmes. Meanwhile, friends and religious leaders rank the lowest for trust.

Huerta says it is “encouraging” that the general public “tend to trust scientists as their main source of information”.

However, he warns Carbon Brief about “social desirability” – a phenomenon in which people respond to surveys in a way that they think will be viewed favourably by others. In this case, it means that “people may report higher trust in scientists and less reliance on social media than they actually practice”, Huerta explains.

Dr Charles Ogunbode is an assistant professor in applied psychology at the University of Nottingham. He is not involved in the paper, but has carried out research on public perceptions of climate change.

He tells Carbon Brief that the relatively low attention and trust shown to family and friends is a “remarkable finding that stands in contrast with conventional knowledge”. He continues:

“Previous psychological research on this topic (generally predominated by western samples) would support an expectation that people would have greater trust in interpersonal social referrents like friends and family…

“I think the findings from the study signal an opportunity to bolster climate knowledge in the global south by widening access to scientific information on climate change.”

Climate knowledge

The survey also assesses the level of climate knowledge of the respondents, by asking them to identify whether a series of statements are true, false, or if they are “not sure”.

More than 80% of respondents correctly identified that the following two statements are correct:

- Climate change is mainly caused by human activities.

- Warming leads to more extreme events, such as droughts, floods and storms.

Conversely, fewer than 20% of people correctly identified the following two statements as false:

- Nuclear power plants emit CO2 during operations.

- Today’s global CO2 concentration has occurred in the past 650,000 years.

Knowledge about climate change was “quite similar” across countries, according to the survey. However, the authors found that women are more likely to respond “not sure” than men.

The study finds that trusting and paying attention to climate scientists was associated with increased climate knowledge, roughly twice the effect size associated with a college degree.

Policy comparison

Early in the survey, respondents were asked to rank how important climate change is for their country on a scale from one to five. On average, all countries ranked climate change above 4.4 on this scale.

However, the survey later asked respondents to rank the 13 government programmes, including climate, healthcare and education, in order of importance.

The authors found that “addressing climate change” ranks at ninth, on average, across the seven countries.

Climate change ranks the highest in Vietnam, where it comes in second behind “decreasing political corruption”.

However, it ranks 10th in Nigeria and South Africa, beating only “improving public transport”, “improving access to credit” and “getting Covid-19 under control”.

Lead author Prof Richard Carson, a professor of economics at the University of California, tells Carbon Brief that asking respondents to rank different issues “provides a much richer picture of the structure of public opinion on climate issues” than asking them to rank issues separately. This, he says, is because it forces respondents to make “direct tradeoffs”.

The survey shows that “people might say that dealing with climate change matters – but this does not mean that they would place it on the leaderboard when it comes to priorities”, he adds.

Huerta – the experimental psychology researcher – tells Carbon Brief that results highlight “a crucial tension”. He explains:

“Athough people show strong concern for climate change, when it comes to allocating scarce public resources, priorities such as health, education, poverty reduction, and security often come first.”

He adds:

“People may genuinely care, but without clear, immediate benefits, climate action is often deprioritised – unlike issues such as air pollution, where the consequences and gains are more tangible.”

The authors also asked survey respondents to rank seven “health-related issues”, with respiratory problems consistently identified as the highest priority.

Huerta says the results show a “disconnection”, adding:

“People rank respiratory illness as a top health concern, but they do not always connect it with climate change more broadly. This highlights a key communication challenge for climate policy.”

Finally, the authors asked respondents to rank their preference for the use of a carbon tax. In keeping with the results above, “spend on education and health” ranks top of the list. This is followed by subsidising solar panels and investing in “clean research and development”.

Dr Stella Nyambura Mbau is a lecturer at Kenya’s Jomo Kenyatta University of Agriculture and Technology and was not involved in the study. She tells Carbon Brief that “the preference for earmarking carbon tax revenue for health, education and renewable energy subsidies aligns with community-based adaptation strategies, such as solar-powered solutions, that address immediate needs while building resilience”.

She suggests that prioritising policies that can tackle climate change alongside other social issues could “bridge the gap between climate action and local priorities”.

Next steps

The authors note that their survey could only be completed by people with access to the internet, meaning that it “systematically underrepresents those with lower income, living in rural areas and who are older”.

Only people over the age of 18 were allowed to complete the survey. Across the countries, the median age of respondents was 31 years old. There was also a slight skew towards men, who made up 55% of the respondents.

As such, some external experts pointed out that results could be skewed.

For example, Prof Tarun Khanna, a professor at Harvard Business School, notes that when ranking uses for carbon taxes, there was low support for policies such as returning money to the poor. He questions whether this could be “because the survey concentrates on a relatively affluent class of people”.

Dr Nick Simpson is chief research officer at the University of Cape Town‘s African Climate and Development Initiative Climate Risk Lab and has led separate research on general public perceptions of climate change in Africa.

He praises the study’s “large, cross-national dataset” and “rigorous statistical techniques”. However, he adds:

“The survey questions focus primarily on mitigation [greenhouse gas emissions prevention and reduction] responsibilities, reflecting a global north bias in climate surveys. [The questions] do not fully capture urgent adaptation concerns or the lived realities of climate vulnerability in low and middle-income countries.”

Future research should incorporate more “adaptation-specific questions” in order to “provide a more holistic understanding of climate action priorities”, he says.

The post Scientists are ‘most trusted’ source of climate information in global-south survey appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Scientists are ‘most trusted’ source of climate information in global-south survey

Climate Change

IPBES: Four key takeaways on how nature loss threatens the global economy

The “undervaluing” of nature by businesses is fuelling its decline and putting the global economy at risk, according to a major new report.

An assessment from the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) outlines more than 100 actions for measuring and reducing impacts on nature across business, government, financial institutions and civil society.

A co-chair of the assessment says that nature loss is one of the most “serious threats” to businesses, but the “twisted reality is that it often seems more profitable to businesses to degrade biodiversity than to protect it”.

The “business and biodiversity” report says that global “finance flows” of more than $7tn (£5.1tn) had “direct negative impacts on nature” in 2023.

The new findings were put together by 79 experts from around the world over the course of three years, in what IPBES described as a “fast-track” assessment.

IPBES is an independent body that gives scientific advice to policymakers about biodiversity and ecosystems.

This is the “first report of its kind” to provide guidance on how businesses can contribute to 2030 nature goals, says IPBES executive secretary Dr Luthando Dziba in a statement.

Below, Carbon Brief explains four key findings from the “summary for policymakers” (SPM), which outlines the main messages of the report.

The full report is due to be released in the coming months after final edits are made.

- Businesses both depend on, and harm, nature

- Current practices ‘do not support’ efforts to halt and reverse biodiversity loss

- Businesses can act now to address their impacts on nature

- Government policies can drive a ‘just and sustainable future’ for nature and people

1. Businesses both depend on, and harm, nature

Businesses of all sizes rely on nature in one way or another, says the report.

The SPM outlines that biodiversity provides many of the goods and services businesses need, such as raw materials from the environment or controlled water flows to reduce flooding during wet seasons and provide water in dry seasons.

Biodiversity also “underpins genetic diversity” that informs the development of products in many industries, including pharmaceuticals and cosmetics.

Individual businesses often do not address their impacts and dependencies on nature, “in part due to their lack of awareness”, the SPM says.

They also often do not have the data or knowledge to “quantify their impacts on dependencies on biodiversity and much of the relevant scientific literature is not written for a business audience”, the report claims. It adds:

“Lack of transparency across value chains, including of the risks and opportunities related to the sustainability of resource extraction, use, reuse and waste management, is a further barrier to action.”

The report says it is well established that businesses depend on biodiversity, but also that the actions of businesses “continue to drive declines in biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people”.

It adds that the size of a business “does not always reflect the magnitude of its impacts”, with companies in sectors such as agriculture, forestry, fishing, electricity, energy and mining having “relatively high” direct impacts on nature.

A “failure” to account for nature as the economy has expanded over the past two centuries has “led to its degradation and unprecedented rates of biodiversity loss”, the SPM says. It adds:

“The decline in biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people has become a critical systemic risk threatening the economy, financial stability and human wellbeing with implications for human rights.”

It is well established that nature loss as a result of “unsustainable use” threatens the “ability of businesses, local economies and whole sectors to function”, the report details.

These risks and others – such as extreme weather events and critical changes to Earth systems – are “among the highest-ranked global risks over the next 10 years”, it adds.

The SPM notes further that it is well established that risks around climate change and biodiversity loss “may interact to amplify social and economic impacts”.

These risks have “disproportionate impacts on developing countries whose economies are more reliant on biodiversity and have more limited technical and financial capacity to absorb shocks”, the report adds.

2. Current practices ‘do not support’ efforts to halt and reverse biodiversity loss

The SPM says that it is well established that current political and economic practices “perpetuate business as usual and do not support the transformative change required to halt and reverse biodiversity loss”.

These practices have “commonly ignored or undervalued biodiversity, creating tension between business actions and the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity”, the report continues.

For example, the report says there is established but incomplete evidence that “time pressures on decision-making and timescales for investment returns and reporting by businesses – with an emphasis on quarterly earnings or annual reporting – are shorter than many ecological cycles”.

This prevents businesses from “adequately” considering nature loss in decision-making, says the SPM.

There is well established evidence that businesses fail to assign adequate value to “biodiversity and many of nature’s contributions to people, such as filtration of pollutants, climate regulation and pollination”, it continues.

As a result, “businesses bear little or no financial cost for negative impacts and may not generate revenue from positive impacts on biodiversity”, leading to “insufficient incentives for businesses to act to conserve, restore or sustainably use biodiversity”.

Prof Stephen Polasky, co-chair of the assessment and a professor of ecological and environmental economics at the University of Minnesota, said in a statement:

“The loss of biodiversity is among the most serious threats to business. Yet the twisted reality is that it often seems more profitable to businesses to degrade biodiversity than to protect it. Business as usual may once have seemed profitable in the short term, but impacts across multiple businesses can have cumulative effects, aggregating to global impacts, which can cross ecological tipping points.”

It is well established that policies from governments can “further accelerate biodiversity decline”, the SPM says.

It notes that, in 2023, global public and private financial spending with direct negative impacts on nature was estimated at $7.3tn.

This figure includes public subsidies that are harmful to nature (around $2.4tn) and private investment in high-impact sectors ($4.9tn), says the report.

Industries harmful to nature include fossil-fuel extraction, mining, deforestation and large-scale meat farming and fishing.

In contrast, just $220bn in public and private finance was directed to activities that contribute to protecting and sustainably using nature in 2023, adds the report.

(In recognition of the need to address public spending on activities that are destructive to nature, countries agreed to reduce biodiversity-harming subsidies by at least $500bn by 2030 as part of a global pact made in 2022.)

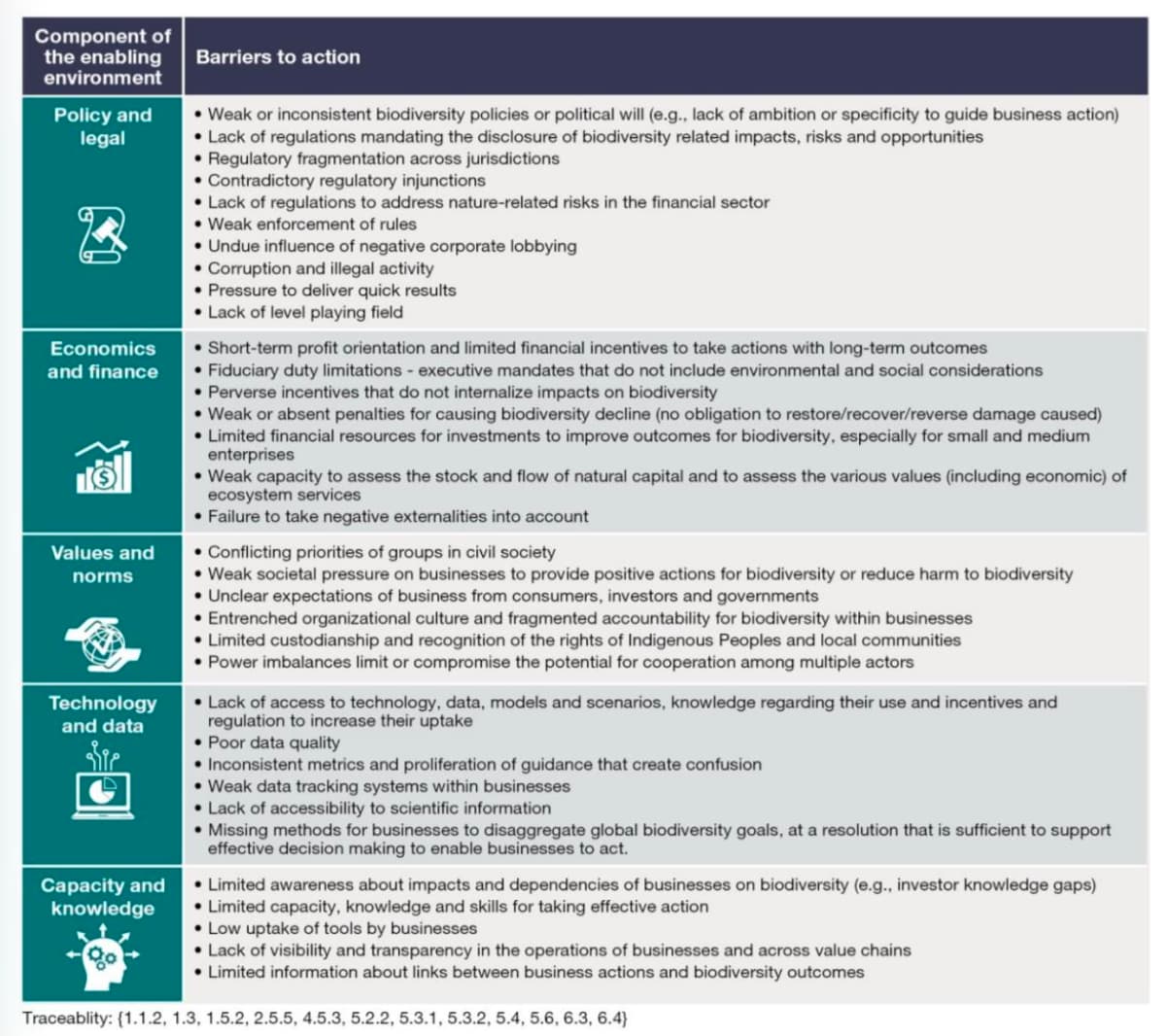

There are additional “barriers to action” facing businesses, ranging from challenging social norms to a lack of capacity, data or technology. These are summarised in the table below.

“These barriers do not affect all actors equally and may disproportionately affect small and medium-sized businesses and financial institutions in developing countries,” adds the report.

3. Businesses can act now to address their impacts on nature

The SPM says it is well established that the “transformative change” required to halt and reverse biodiversity loss requires action from “all businesses”.

However, the report continues that it is also well established that the current level of business action is “insufficient” to deliver this “transformative change”. This is, in part, because the “enabling environment is missing”, it says.

IPBES says all businesses have a responsibility to act, even if this responsibility is not shared “evenly”.

“Priority actions” that businesses should take differ depending on the size of the firm, the sector in which it operates in, as well as the company structure and its “relationship with biodiversity”, the report notes.

The exact actions businesses should pursue also depends on companies’ “degree of control and influence over stakeholders”, it says.

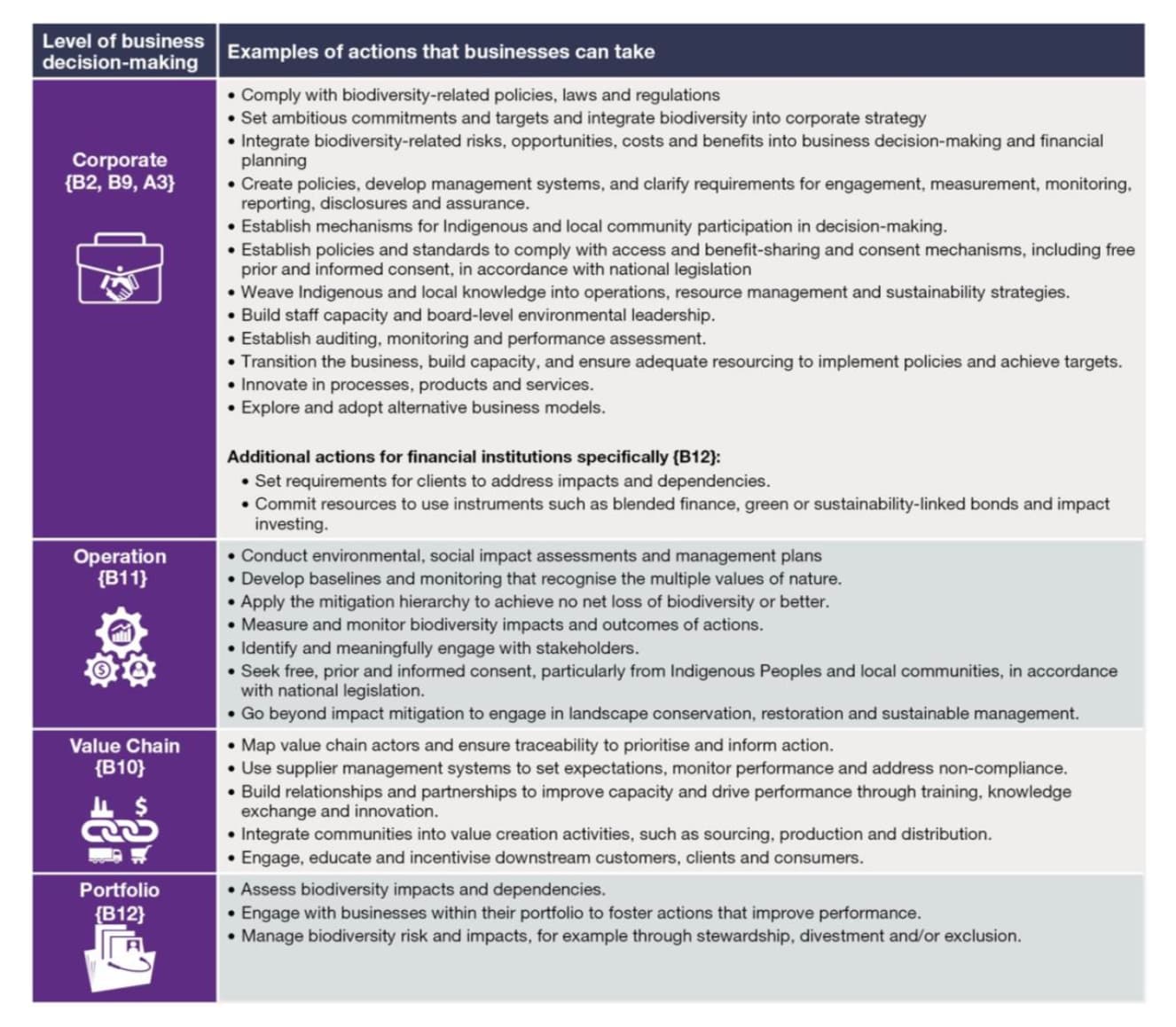

According to the report, firms can act across four “decision-making levels” – corporate, operations, value chain and portfolio – to measure and address impacts on biodiversity.

(“Corporate” refers to decisions focused on overarching strategy, governance and direction of the business; “operations” to day-to-day activities; “value chain” to the system and resources required to move a product or service from supplier to customer; and “portfolio” to investments and business assets).

The SPM sets out a series of examples for how businesses can act across all four levels. These are summarised in the table below.

At a corporate level, the report notes that firms can establish ambitious governance and frameworks that can then have a ripple effect across the other levels, according to the report. This includes the integration of biodiversity commitments and targets into corporate strategy.

The SPM says that corporate biodiversity targets are “most effective” when they are aligned with “national and global biodiversity objectives” and “take into consideration a business’s impacts and dependencies on biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people”.

At an operations level, businesses should focus on ensuring that their operations are located and managed in a way that benefits biodiversity, IPBES says. Environmental and social impact assessments and management plans that are supported by “credible monitoring of both actions and biodiversity outcomes” can underpin this effort, the SPM notes.

It says it is well established that using the “mitigation hierarchy” framework can help businesses deliver “lasting outcomes on the ground”. (The framework guides users towards limiting as far as possible the negative impacts on biodiversity from development projects by first avoiding, then minimising, restoring and offsetting impacts.)

Next, the report notes there are actions businesses can take to drive change within its broader spheres of influence, including suppliers, retailers, consumers and peers within industry. This is important, the SPM notes, as significant impacts and dependencies on biodiversity and nature “accrue” across the lifecycle of products or services, especially those that rely on raw materials.

The report notes there is established but incomplete evidence that efforts to “map” company value chains and improve traceability by linking products and materials to suppliers, locations and impacts can help “identify risks and prioritise actions”.

While noting that “mapping” beyond direct suppliers “often remains challenging” for businesses, the report adds:

“Examples at the corporate and value chain levels exist, such as companies in the chocolate industry that have made advances in recording biodiversity dependencies to improve business decisions through full traceability of materials and improved supplier control mechanisms.”

Elsewhere, the SPM notes that there is also established but incomplete evidence that consumer-focused measures – such as product labelling, education and incentives – can “shape behaviour and improve transparency”. However, it cautions that the effectiveness of these strategies is “constrained by consumer scepticism, certification costs and business models reliant on unsustainable consumption”.

The SPM also highlights that, at a “portfolio” level, financial institutions can shift finance away from harmful activities – for instance, companies whose products drive deforestation – and towards business activities with positive impacts for biodiversity and nature.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Matt Jones, co-chair of the report, explains the rationale behind including options for how businesses can address biodiversity impacts in the document:

“Businesses and governments in different countries are coming at this from a very different perspective. So we can’t present a set of really prescriptive ‘how tos’…but we can present a huge number of options for action that businesses, governments, financial institutions and civil society and other actors can all take.”

Elsewhere, the report says it is well established that “robust, transparent and credible reporting of actions and outcomes” is required to “inspire others”.

4. Government policies can drive a ‘just and sustainable future’ for nature and people

Both governments and financial institutions can set policies and create incentives to protect biodiversity and stem its decline, says the SPM.

According to the report, the types of policies that governments can put in place that have an influence over business include:

- Fiscal policies, such as subsidies and taxes.

- Land use or marine spatial planning and zoning, such as designating new national parks or areas protected for nature.

- Permitting for business activities that affect nature – for example, by requiring environmental impact assessments.

- Public procurement policy (rules for how governments purchase goods and services).

- Controls on advertising and the creation of standards to prevent “greenwashing”.

Governments can also promote action through paying for ecosystem services, creating environmental markets and through “multilateral benefit-sharing mechanisms”, which set out rules for ensuring profits from nature are shared equally, says the SPM.

It says this includes the Cali Fund, a fund that businesses can voluntarily pay into after reaping benefits from genetic resources found in biodiverse countries.

(The fund was agreed in 2024 with expectations that it could generate up to billions of dollars for conservation, but it has so far only attracted $1,000.)

Governments could also promote action by phasing out or reforming subsidies that are harmful for nature, as well as fostering positive incentives, according to the report.

Overall, governments can work with other actors to create an “enabling environment” to “incentivise actions that are beneficial for businesses, biodiversity and society for a just and sustainable future”, says the SPM. It adds:

“Creation of an enabling environment that provides incentives for the conservation and sustainable use of biodiversity and nature’s contributions to people could align what is profitable with what is good for biodiversity and society.

“Creating this enabling environment would result in businesses and financial institutions being positive agents of change in transforming to a just and sustainable economic system, by addressing their impacts on biodiversity loss, climate change and pollution, which are all interconnected.”

The post IPBES: Four key takeaways on how nature loss threatens the global economy appeared first on Carbon Brief.

IPBES: Four key takeaways on how nature loss threatens the global economy

Climate Change

Vanuatu pushes new UN resolution demanding full climate compensation

Countries responsible for climate change could be required to pay “full and prompt reparation” for the damage they have caused, under a new United Nations resolution being pursued by the Pacific island state of Vanuatu, an initial draft shows.

The resolution seeks to turn into action last year’s landmark advisory opinion from the International Court of Justice (ICJ), which found that states have a legal obligation to prevent climate harm and that breaches of this duty could expose them to compensation claims from affected countries.

Under the “zero draft” of the resolution seen by Climate Home News, the UN’s General Assembly, its main policy-making body, would also demand that countries stop any “wrongful acts” contributing to rising emissions, which may include the production and licensing of planet-heating fossil fuels.

Gas flaring soars in Niger Delta post-Shell, afflicting communities

‘Demand’ is the strongest verb calling for an obligation to comply in UN language, but it is rarely used in a resolution.

Countries would also be called upon to respect their legal obligations by enacting national climate plans consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5C and by adopting appropriate policies, including measures to “ensure a rapid, just and quantified phase-out of fossil fuel production and use”, the document shows.

End of March vote targeted

The draft, meant as a starting point for negotiations, was circulated last week by the government of Vanuatu following discussions with a dozen nations, including the Netherlands, Colombia and Kenya.

Countries are expected to take part in informal consultations between February 13-17 aimed at agreeing on wording that would secure broad support among UN member states, according to a statement from Vanuatu, which also led the diplomatic drive for the ICJ’s advisory opinion. A vote on the follow-up resolution could take place by the end of March, it added.

Ralph Regenvanu, Vanuatu’s climate minister, said respecting the court’s decision is “essential for the credibility of the international system and for effective collective action”.

“At a time when respect for international law is under pressure globally, this initiative affirms the central role of the International Court of Justice and the importance of multilateral cooperation,” he added in written comments.

New damage register and reparation mechanism

If adopted in its current form, the draft resolution would also create an “International Register of Damage”, which is described as a comprehensive and transparent record of evidence on loss and damage linked to climate change.

It would also ask the UN secretary-general to put forward proposals for a climate reparation mechanism that could coordinate and facilitate the resolution of compensation claims and promote financial models to help cover climate-related damage.

The fledgling Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD) – set up under the UN climate change regime – is set to hand out money to the first set of initiatives aimed at addressing climate-driven destruction later this year. However, the just-over $590 million currently in the fund’s coffers is dwarfed by the scale of need in developing countries, with loss and damage costs estimated to reach up to $400 billion a year by 2030.

Like other small island nations, Vanuatu is among the world’s most vulnerable countries to the effects of climate change, while having contributed the least to global warming. Last year’s ICJ decision stemmed from a March 2023 resolution led by the Pacific nation asking the world’s top court to define countries’ legal obligations in relation to climate change.

Regenvanu said in September 2025 that it was important to follow up the ICJ ruling with a new UNGA resolution because it could be approved by a majority vote, while progress can be blocked in other fora like the UN climate negotiations that require consensus for decisions.

The post Vanuatu pushes new UN resolution demanding full climate compensation appeared first on Climate Home News.

Vanuatu pushes new UN resolution demanding full climate compensation

Climate Change

China maximises battery recycling to shore up critical mineral supplies

Even the busiest streets of Shanghai have become noticeably quieter as sales of electric vehicles (EVs) skyrocketed in China, with charging points mushrooming in residential compounds, car parks and service stations across the megacity.

Many Chinese drivers have upgraded their conventional vehicles to electric ones – or already replaced old EVs with newer models – incentivised by the government’s generous trade-in policies, or tempted by the latest hi-tech features such as controls powered by artificial intelligence (AI).

“Different from conventional cars, EVs are more like fast-moving consumer goods, like smartphones,” explained Mo Ke, founder and chief analyst of Tianjin-based battery-research firm, RealLi Research. Their digital systems can become outdated quickly, so Chinese people typically change their EVs after five or six years while a conventional car can be driven much longer, he told Climate Home News.

EV sales surpassed 16 million in China last year. Roughly 10% of all vehicles on the road were electric, and half of all new vehicles sold carried a green EV number plate, with an average of 45,000 EVs rolling off the production lines each day.

But while fast-growing EV uptake is good news for Chinese EV and battery manufacturers, it is creating a huge volume of spent batteries.

Tsunami of spent batteries

Last year, China generated nearly 400,000 tonnes of old or damaged power batteries, largely consisting of vehicle batteries, according to government data. That is projected to rise to one million tonnes per year in 2030, officials forecast.

The growing waste problem has spurred the government to launch a series of new policies aimed at regulating the country’s battery recycling industry, which though well-established is marked by a high degree of informality – especially in the lucrative repurposing sector where discarded EV batteries are given a new lease of life in less energy-intensive uses, such as power storage.

China is determined to build a “standardised, safe and efficient” recycling system for batteries, Wang Peng, a director at China’s Ministry of Industry and Information Technology, told a press conference as the government launched a recycling industry push in mid-January.

A policy paper published by the government last month detailed Beijing’s plans to mandate end-of-life recycling for EVs together with their batteries to prevent them from entering the grey, informal market, and establish a digital system to track the lifecycle of every battery manufactured in the country. Under the plans, EV and battery makers will be held responsible for recycling the batteries they produce and sell.

“The volume of the Chinese market is too big, so it has to take actions ahead of other countries,” Mo said, adding that he expected the government to release more details about implementation of the plans in the near future.

Critical minerals choke point

China’s strategy for the battery recycling sector could also prove a boon for the world’s largest battery producer by bolstering its supply of minerals such as lithium, cobalt, nickel and manganese.

Along with the looming large-scale battery retirement, policymakers’ focus on battery recycling also reflects concern about critical minerals supplies, said Li Yifei, assistant professor of environmental studies at New York University Shanghai. “The government also felt the increasing pressure of securing resources,” he told Climate Home News.

“When you set up an efficient battery-recycling system, you essentially secure a new source for critical minerals, and that can help you enhance economic security. That’s why the industry is so important,” Lin Xiao, chief executive of Botree Recycling Technologies, a Chinese company offering battery-recycling solutions, told Climate Home News.

Cobalt and nickel-free electric car batteries boom in “good news” for rainforests

China dominates global refining of several minerals critical for producing EV batteries, but it still relies on imports of the raw materials – a choke point Beijing is acutely aware of, industry experts say.

China imports more than 90% of its cobalt, nickel and manganese, which are important ingredients for EV batteries, Hu Song, a senior researcher with the state-run China Automotive Technology and Research Centre, told China’s CCTV state broadcaster in June 2025. For lithium, the figure was around 60% in 2024, according to a separate report.

“If [those] resources cannot be recycled, then we will keep facing strangleholds in the future,” Hu said.

Big players gain ground

Spent EV batteries can be reused in settings that have lower energy requirements, such as in two-wheelers or energy-storage systems. When they become too depleted for repurposing, they can be scrapped and shredded into “black mass”, a powdery mixture containing valuable metals that can be recovered.

Reflecting the size of China’s EV market, the country already dominates global battery recycling capacity. It is home to 78% of the world’s battery pre-treatment capacity, which is for scrapping and shredding, and 89% of the capacity for refining black mass, according to 2025 forecasts by Benchmark Mineral Intelligence, a UK firm tracking battery supply chains.

A number of large corporate players have emerged in the sector in recent years.

Huayou Cobalt, a major producer of battery minerals, has built a business model for recycling, repurposing and shredding old batteries, as well as refining black mass and making new batteries using recovered materials.

It recently signed a deal with Encory, a joint venture between BMW and Berlin-based environmental service provider Interzero, to develop cutting-edge battery-recycling technologies, with their first joint factory set to open in China this year.

Suzhou-based Botree Recycling Technologies has developed various solutions to turn retired power batteries into new ones. Meanwhile, Brunp Recycling, the recycling arm of Chinese battery giant CATL, has built large factories to recycle lithium iron phosphate (LFP) batteries, a type of lithium battery that does not use nickel or cobalt, as well as nickel manganese cobalt (NMC) batteries, which are more popular outside of China.

But Mo, of RealLi Research, said much remains to be done to regulate and formalise the battery recycling industry.

Underground workshops

Across China, small underground workshops plague the repurposing sector, rebundling depleted batteries for sale without following industry standards or complying with health and safety requirements.

Because these operators have lower operational costs, they are able to offer higher prices to EV owners to buy their old batteries, undercutting formal recycling companies.

“This creates distortions in the market where legitimate players, who invest in proper detection, hazardous waste treatment and compliance, struggle to compete purely on price,” a spokesperson at CATL, the world’s largest battery manufacturer, told Climate Home News.

Despite such challenges, CATL’s Brunp subsidiary produced 17,100 tonnes of lithium in 2024 from the 128,700 tonnes of depleted batteries it recycled that year, according to CATL’s annual report.

Recycling expertise in demand

Since it was founded in 2019, Botree has formed partnerships with several major clients, which together recycle about half of China’s power batteries, the company’s CEO Lin said.

As other countries grapple with rising volumes of spent batteries, Chinese recyclers are also finding new foreign markets for their know-how.

Botree has joined forces with Spanish consulting firm ILUNION and renewable energy company EFT-Systems to build a factory to recycle LFP batteries in Valladolid.

The plant, scheduled to start operation in 2027, will be able to recycle 6,000 tonnes of LFPs annually when it opens, accounting for roughly 15% of demand in the Spanish market.

“(The companies) tell us what batteries they recycle and what battery materials they want to regenerate,” Lin said. “We can design a complete process for them.”

The post China maximises battery recycling to shore up critical mineral supplies appeared first on Climate Home News.

China maximises battery recycling to shore up critical mineral supplies

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Renewable Energy2 years ago

GAF Energy Completes Construction of Second Manufacturing Facility