Rebecca Brown is president and CEO of the Center for International Environmental Law. Lien Vandamme is its senior campaigner on human rights and climate change.

The world doesn’t just need stronger climate targets. It needs a fairer, faster and more accountable multilateral system to deliver climate action.

This November, with the world gathered in Belém, Brazil, for COP30, the negotiations unfold against a backdrop of a deepening climate crisis and rising frustration with the slow pace of progress.

These talks matter because the UN climate process is the world’s best platform for much-needed global action on the climate crisis. But after three decades, the process must evolve to meet the moment – which means changing the rules that too often delay action, dilute ambition and disconnect decisions from science, equity and the law.

Powerful countries use procedural deadlock to block ambition. Polluting countries and corporations exert influence to protect their interests and weaken outcomes. And too often, the people most affected by the climate emergency are sidelined or excluded from the decisions that affect them the most.

Given its global nature, effective multilateralism is the only way out of the climate crisis. At COP30, leaders have a choice to continue with the status quo or revise the rules to deliver climate justice.

Reform of UN climate talks

The case for reform is undeniable.A systemic lack of compliance and accountability demands a serious, good-faith effort to reform the system.

For example, this year was supposed to mark a milestone, as all countries were expected to submit their new plans – known as Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs) – to scale up their ambition, bringing us closer to truly limiting warming to 1.5°C. But around half of the plans have yet to arrive.

UN accepts overshooting 1.5C warming limit – at least temporarily – is “inevitable”

Many of the plans that have been submitted largely missed the mark to keep warming below the legal limit of 1.5C. They avoid the one measure that science demands: an explicit fossil fuel phaseout. And the financing that developing countries need to raise ambition in their climate plans remains scarce.

Reforming the UN climate talks is therefore not procedural housekeeping; it is climate action. Without reform, the best science and strongest legal obligations will continue to collide with an outdated process. With reform, we can accelerate the phase-out of fossil fuels, deliver real finance at scale and protect human rights.

Principles for reform

Efforts are already underway. Calls for reform are coming from inside and outside the process: from civil society and experts to former negotiators and even the UNFCCC executive secretary and the COP30 presidency.

States are also testing the waters, with a recent call from Panama to allow for majority decision-making and Vanuatu naming the need for additional architecture to force states to comply with their obligations. The momentum is real.

But to succeed, this reform must be grounded in a few basic principles.

First, voting needs to be possible when consensus fails. When one or two holdouts block the ambition the world needs, the majority must be allowed to move without them.

Second, fossil fuel interests must not warp climate action priorities. Fossil fuel and other polluting industry lobbyists outnumbered national delegations of almost every country at recent talks. It is time to enforce robust conflict of interest rules to limit the influence of those whose business model depends on delay and denial.

This has been done before. The World Health Organization excluded Big Tobacco from public health conversations. Climate talks should do the same with Big Oil.

Top UN court paves way to lawsuits over inadequate climate finance

Third, there must be meaningful accountability. Shiny declarations from states and private actors made at COPs need criteria, monitoring, and compliance. States must be held accountable for the commitments they make.

While the Paris Agreement’s compliance mechanisms may be toothless by design, the International Court of Justice recently affirmed that states are responsible for meeting their climate obligations and can be held liable if they don’t.

They have a choice to make: set up legitimate accountability mechanisms under the climate regime or face their responsibilities in courts around the world.

Human rights at its core

Finally, reform also needs to guarantee human rights protections and civic space at every COP, and make negotiations participatory, inclusive and transparent. Civil society and the public have the right to know what is being decided in their name, and to challenge decisions when they fall short.

At its core, this reform is about restoring faith in international cooperation to solve global crises. It is about making the process stronger, fairer and more capable of delivering what science and justice require.

Comment: It’s time for majority voting at UN climate summits

In Belém, governments have the opportunity to begin closing the gap between promises and action, not just through stronger targets and better policies, but by changing the rules of the game.

The science is clear. The law is clear. Now, the process must catch up.

If COP30 is to be remembered as a turning point, it won’t be because the system was perfect, but because governments decided to make it better.

The post Not another COP-out: We must rewrite the rules of the UN climate talks appeared first on Climate Home News.

Not another COP-out: We must rewrite the rules of the UN climate talks

Climate Change

Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding

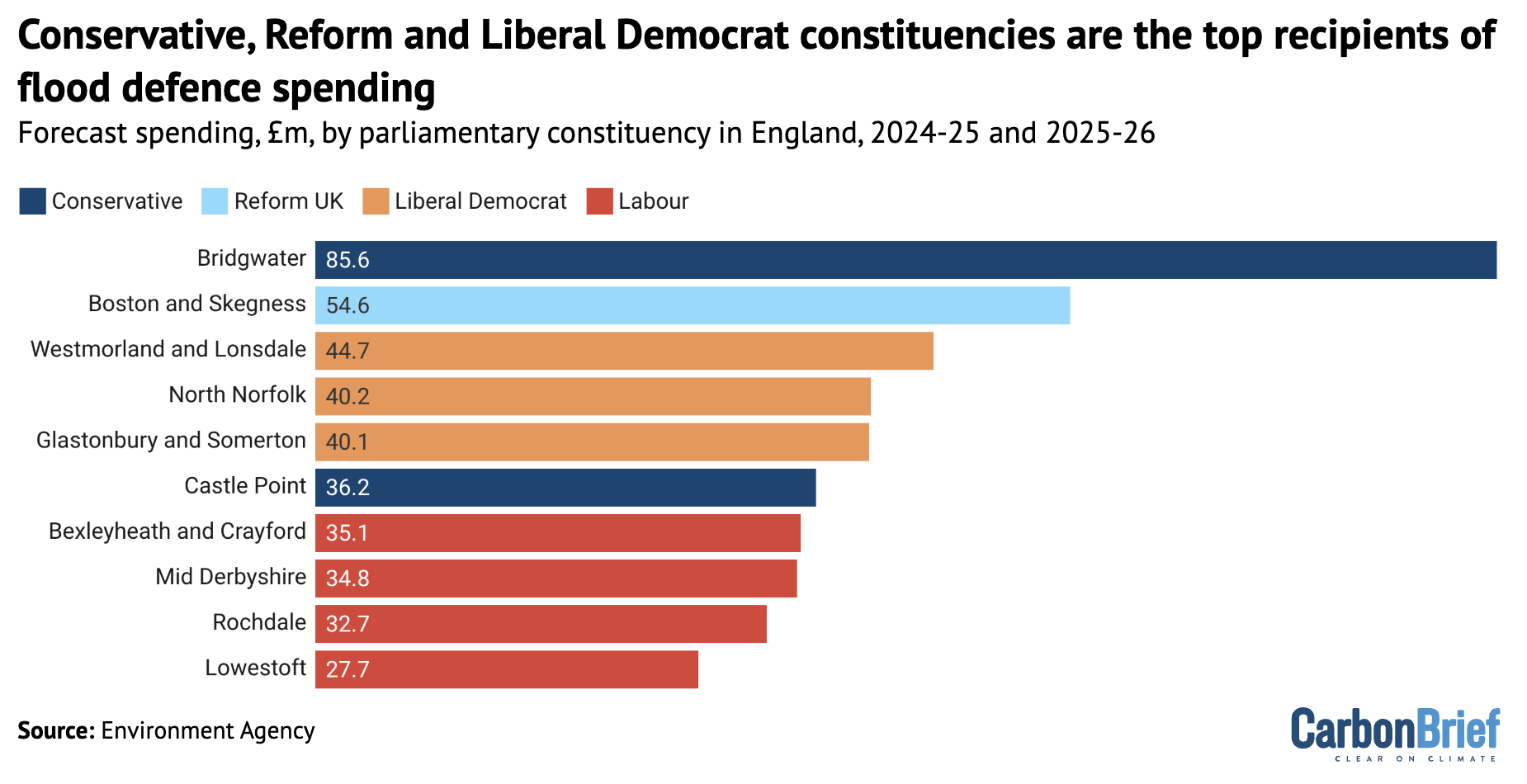

The Lincolnshire constituency held by Richard Tice, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of the hard-right Reform party, has been pledged at least £55m in government funding for flood defences since 2024.

This investment in Boston and Skegness is the second-largest sum for a single constituency from a £1.4bn flood-defence fund for England, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

Flooding is becoming more likely and more extreme in the UK due to climate change.

Yet, for years, governments have failed to spend enough on flood defences to protect people, properties and infrastructure.

The £1.4bn fund is part of the current Labour government’s wider pledge to invest a “record” £7.9bn over a decade on protecting hundreds of thousands of homes and businesses from flooding.

As MP for one of England’s most flood-prone regions, Tice has called for more investment in flood defences, stating that “we cannot afford to ‘surrender the fens’ to the sea”.

He is also one of Reform’s most vocal opponents of climate action and what he calls “net stupid zero”. He denies the scientific consensus on climate change and has claimed, falsely and without evidence, that scientists are “lying”.

Flood defences

Last year, the government said it would invest £2.65bn on flood and coastal erosion risk management (FCERM) schemes in England between April 2024 and March 2026.

This money was intended to protect 66,500 properties from flooding. It is part of a decade-long Labour government plan to spend more than £7.9bn on flood defences.

There has been a consistent shortfall in maintaining England’s flood defences, with the Environment Agency expecting to protect fewer properties by 2027 than it had initially planned.

The Climate Change Committee (CCC) has attributed this to rising costs, backlogs from previous governments and a lack of capacity. It also points to the strain from “more frequent and severe” weather events, such as storms in recent years that have been amplified by climate change.

However, the CCC also said last year that, if the 2024-26 spending programme is delivered, it would be “slightly closer to the track” of the Environment Agency targets out to 2027.

The government has released constituency-level data on which schemes in England it plans to fund, covering £1.4bn of the 2024-26 investment. The other half of the FCERM spending covers additional measures, from repairing existing defences to advising local authorities.

The map below shows the distribution of spending on FCERM schemes in England over the past two years, highlighting the constituency of Richard Tice.

By far the largest sum of money – £85.6m in total – has been committed to a tidal barrier and various other defences in the Somerset constituency of Bridgwater, the seat of Conservative MP Ashley Fox.

Over the first months of 2026, the south-west region has faced significant flooding and Fox has called for more support from the government, citing “climate patterns shifting and rainfall intensifying”.

He has also backed his party’s position that “the 2050 net-zero target is impossible” and called for more fossil-fuel extraction in the North Sea.

Tice’s east-coast constituency of Boston and Skegness, which is highly vulnerable to flooding from both rivers and the sea, is set to receive £55m. Among the supported projects are beach defences from Saltfleet to Gibraltar Point and upgrades to pumping stations.

Overall, Boston and Skegness has the second-largest portion of flood-defence funding, as the chart below shows. Constituencies with Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs occupied the other top positions.

Overall, despite Labour MPs occupying 347 out of England’s 543 constituencies – nearly two-thirds of the total – more than half of the flood-defence funding was distributed to constituencies with non-Labour MPs. This reflects the flood risk in coastal and rural areas that are not traditional Labour strongholds.

Reform funding

While Reform has just eight MPs, representing 1% of the population, its constituencies have been assigned 4% of the flood-defence funding for England.

Nearly all of this money was for Tice’s constituency, although party leader Nigel Farage’s coastal Clacton seat in Kent received £2m.

Reform UK is committed to “scrapping net-zero” and its leadership has expressed firmly climate-sceptic views.

Much has been made of the disconnect between the party’s climate policies and the threat climate change poses to its voters. Various analyses have shown the flood risk in Reform-dominated areas, particularly Lincolnshire.

Tice has rejected climate science, advocated for fossil-fuel production and criticised Environment Agency flood-defence activities. Yet, he has also called for more investment in flood defences, stating that “we cannot afford to ‘surrender the fens’ to the sea”.

This may reflect Tice’s broader approach to climate change. In a 2024 interview with LBC, he said:

“Where you’ve got concerns about sea level defences and sea level rise, guess what? A bit of steel, a bit of cement, some aggregate…and you build some concrete sea level defences. That’s how you deal with rising sea levels.”

While climate adaptation is viewed as vital in a warming world, there are limits on how much societies can adapt and adaptation costs will continue to increase as emissions rise.

The post Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding

Climate Change

US Government Is Accelerating Coral Reef Collapse, Scientists Warn

Proposed Endangered Species Act rollbacks and military expansions are leaving the Pacific’s most diverse coral reefs legally defenseless.

Ritidian Point, at the northern tip of Guam, is home to an ancient limestone forest with panoramic vistas of warm Pacific waters. Stand here in early spring and you might just be lucky enough to witness a breaching humpback whale as they migrate past. But listen and you’ll be struck by the cacophony of the island’s live-fire testing range.

US Government Is Accelerating Coral Reef Collapse, Scientists Warn

Climate Change

Satellites Reveal New Climate Threat to Emperor Penguins

Ice loss in the Antarctic Ocean may be killing the sea birds during their molting season.

Each year for millennia, emperor penguins have molted on coastal sea ice that remained stable until late summer—a haven during a span of several weeks when it’s dangerous for the mostly aquatic birds to enter the ocean to feed because they are regrowing their waterproof feathers.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits