Nearly a tenth of global climate finance could be under threat as US president Donald Trump’s aid cuts risk wiping out huge swathes of spending overseas, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Last year, the US announced that it had increased its climate aid for developing countries roughly seven-fold over the course of Joe Biden’s presidency, reaching $11bn per year.

This likely amounts to more than 8% of all international climate finance in 2024.

However, any progress in US climate finance has been thrown into disarray by the new administration.

Trump has halted US foreign aid and threatened to cancel virtually all US Agency for International Development (USAid) projects, with climate funds identified as a prime target.

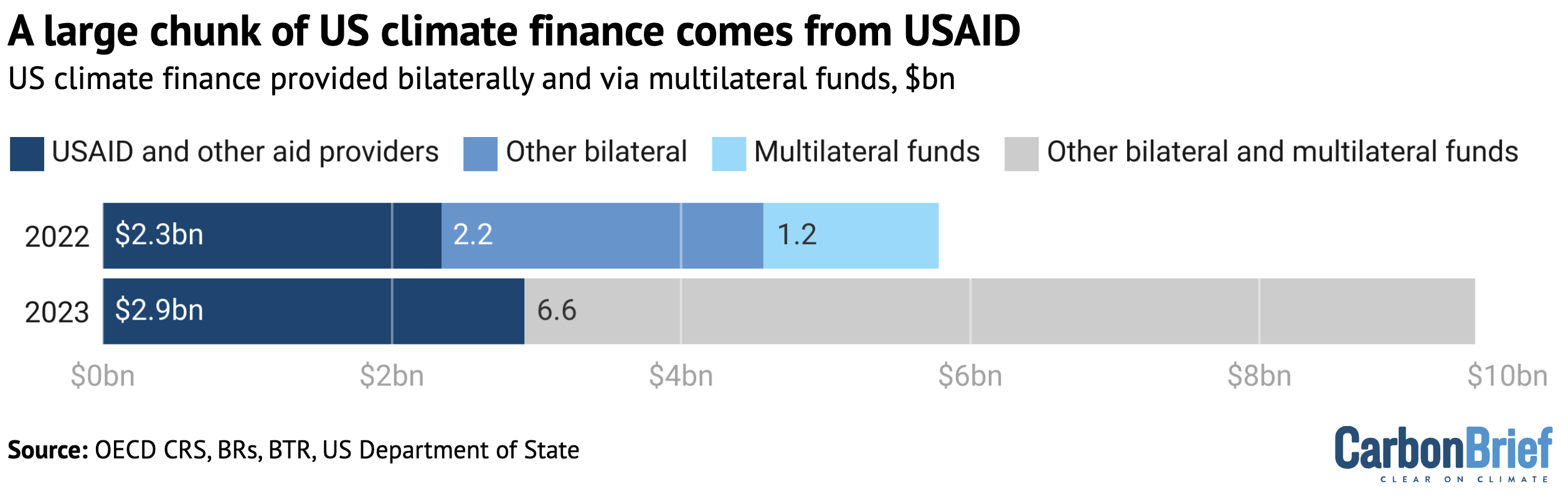

USAid has provided around a third of US climate finance in recent years, reaching nearly $3bn in 2023, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Another $4bn of US funding for the UN Green Climate Fund (GCF) has also been cancelled by the president’s administration.

One expert tells Carbon Brief that more climate funds will likely end up on the “cutting block”.

Another warns of an “enormous gulf” to meeting the new global $300bn climate-finance goal nations agreed last year, if the US stops reporting – let alone providing – any official climate finance.

Carbon Brief’s analysis draws together available data to explain how the Trump administration’s cuts endanger global efforts to help developing countries tackle climate change.

- How much did climate finance increase under Biden?

- What are the climate impacts of cutting USAid?

- Are other sources of climate finance at risk?

- Methodology

How much did climate finance increase under Biden?

The US is by far the world’s largest economy and biggest historical emitter of carbon dioxide (CO2).

This means that, while it is the fourth-biggest national provider of international climate finance, its overall share is low relative to the nation’s wealth and responsibility for climate change. As a result, the US has long been seen as a laggard in this area.

The US provides 0.24% of its gross national income (GNI) as aid for developing countries, which includes some climate funding. This is the same share as the Czech Republic, a nation with a per-capita GNI three times smaller.

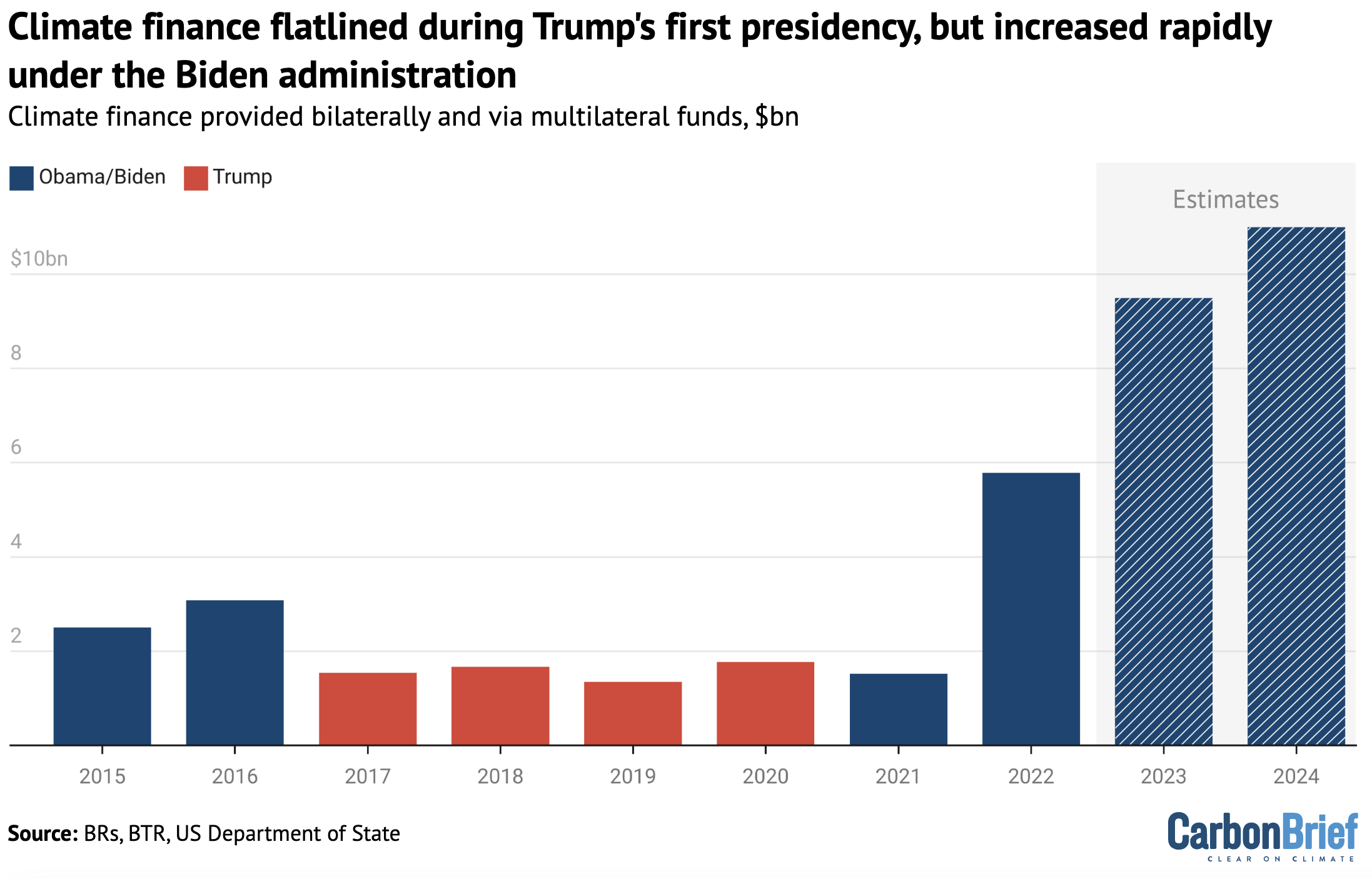

US climate-finance contributions stalled during Trump’s first four-year term as president, when other developed countries were ramping up to meet their target of providing and mobilising $100bn a year for developing countries by 2020.

A shift in focus came when Biden became president in 2021. He established an international climate finance plan to scale up US efforts, in line with US obligations under the Paris Agreement.

Biden also announced that the US would reach $11.4bn in annual climate finance by 2024.

This goal was achieved, according to “preliminary estimates” announced by the US during the COP29 climate summit at the end of 2024. These estimates, which are unlikely to be confirmed by the new administration, are shown in the chart below.

The figures are based predominantly on “bilateral” climate finance reported to the UN. They also include US finance distributed via multilateral climate funds, such as the Global Environment Facility (GEF) and the GCF.

Bilateral climate finance largely comes from aid programmes with climate benefits, such as supporting a geothermal project in the Philippines, investing in “climate-smart” agriculture in Bangladesh, or improving water security in Niger.

The US significantly increased its contribution towards climate finance during the Biden administration. Ramping up relevant US aid projects and multilateral funding helped developed countries to hit the $100bn climate-finance target – albeit two years late in 2022.

The $11bn reported by the US in 2024 would be the equivalent of 21% of all bilateral and multilateral climate fund inputs that year – up from around 4% under the previous Trump presidency. These funds are shown by the blue bars in the figure below.

(Estimates for 2023 and 2024 assume a steady rise in climate finance from sources beyond the US, as official figures beyond then have not been released. See Methodology for more information.)

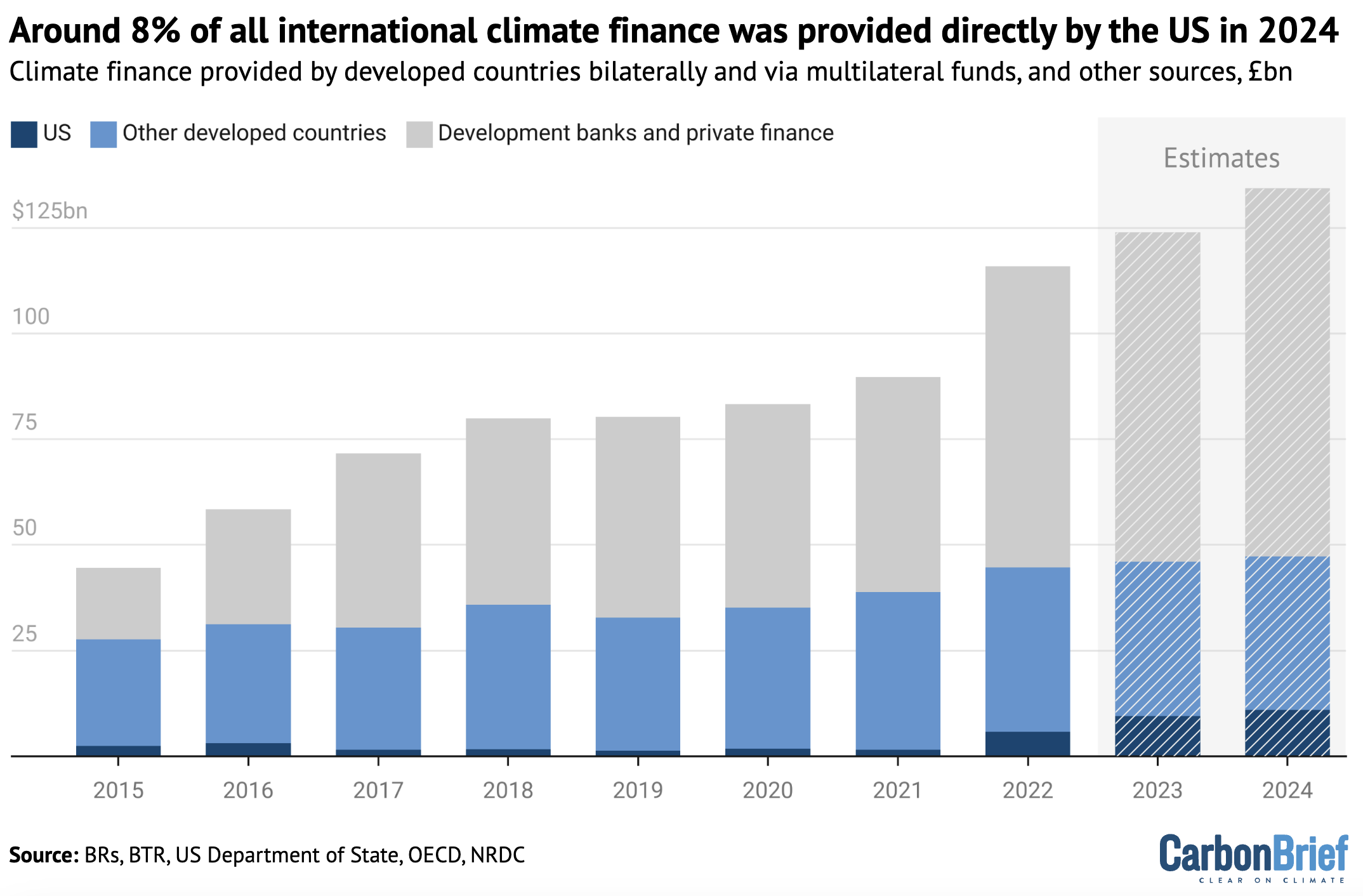

Even when considering other sources of international climate finance – specifically multilateral development banks (MDBs) and “mobilised” private finance shown in grey in the figure below – the US has contributed a sizable share in recent years.

After lingering around 2% during the last Trump administration, the US share of total climate finance roughly quadrupled to more than 8% in 2024, Carbon Brief analysis suggests.

It is also worth noting that the US, as the biggest shareholder at the World Bank and a major shareholder at other MDBs, can be linked to a large portion of their finance. This contribution is not factored into official US reporting, so it has not been included in this analysis.

Even accounting for MDB contributions, US climate finance spending is still far lower than its “fair share”, based on its historical responsibility for climate change and ability to pay. Some analysts have put the US fair share as high as 40-50% of climate finance overall.

What are the climate impacts of cutting USAid?

Upon taking office for the second time in January 2025, Trump immediately took aim at international aid spending and climate action with a flurry of executive orders.

One order announced plans to withdraw the US from the Paris Agreement and criticised such treaties for “steer[ing] American taxpayer dollars to countries that do not require, or merit, financial assistance”. It also “revoked and rescinded” Biden’s international climate finance plan.

In another executive order, Trump announced a “pause” on US foreign aid “for assessment of programmatic efficiencies and consistency with US foreign policy”.

USAid handles 60% of US foreign aid – more than $43bn in 2023 – while the State Department oversees most of the remainder. Trump says he wants to “close [USAid] down” and his advisor Elon Musk has called it a “criminal organisation”.

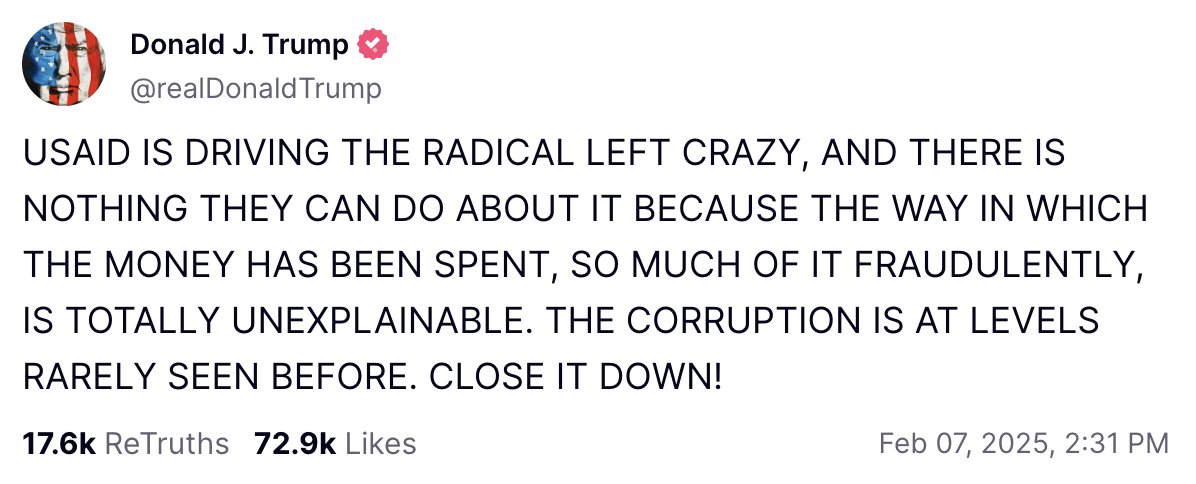

Source: Truth Social.

Trump requires the approval of Congress to repurpose USAid funds or, indeed, abolish the agency. His administration’s actions have, therefore, been described as “illegal” and “unconstitutional” by senior Democrats and aid workers.

Yet, despite lawsuits and court orders instructing the administration to lift the pause, it has since stated its intention to eliminate more than 90% of USAid contracts and, more widely, $60bn of US foreign aid.

This would have major implications for US climate finance.

News outlets have reported on the climate-related programmes at risk, sometimes stating that USAid has funded half a billion dollars of climate programmes annually in recent years.

This figure, while based on USAid’s own reporting of its clean energy, climate adaptation and nature projects, is a significant underestimate of its total climate-finance contributions.

Carbon Brief analysis suggests that USAid contributed $2.8bn of climate finance in 2023, the latest year for which data is available. Other US departments with aid contributions in the OECD database contributed smaller sums, bringing total climate spending up to $2.9bn.

This equates to around a third of US climate finance that year. If a similar share from these departments was counted as climate finance in 2024, it would amount to nearly $4bn, Carbon Brief finds.

(These are estimates based on “climate-related” aid data reported to the OECD. See Methodology for more details.)

Climate-finance experts tell Carbon Brief that these higher figures align with the fact that many aid projects targeting other issues, such as agriculture, have climate components.

Dr Ed Carr, a centre director at Stockholm Environment Institute US who has previously worked at USAid, tells Carbon Brief:

“The way that the Biden administration was doing stuff and the way that [former president Barack] Obama before was doing stuff, [was to] start to weave a degree of climate sensitivity into everything…So, basically, a huge percentage of programmes [are] working on some aspect of climate.”

Unlike many forms of climate finance, USAid projects include lots of grant-based funding, which many developing countries view as preferable to loans and better suited to supporting climate adaptation.

Relevant projects backed by USAid in recent years include support for a food-security programme in Ethiopia, upgrading a dam in Pakistan and protecting water supplies in Peru.

The Trump administration has made it clear that “climate” is one of the issues that it is scrutinising as it assesses aid projects for consistency with what it defines as US interests. A survey sent to grant recipients several weeks after the initial executive order asks:

“Can you confirm this is not a climate or ‘environmental justice’ project or include such elements?”

Are other sources of climate finance at risk?

The remaining billions in climate finance are handled by more than a dozen organisations, distributing grants, loans, development finance and export credits.

Around $1.2bn of US climate finance in 2022 was paid into international funds, including the GEF. This amounts to a fifth of the total US climate finance that year.

The Biden administration did not release a breakdown of how much money went to these funds in 2023 and 2024. However, in 2023 the country paid out $1bn for the GCF alone.

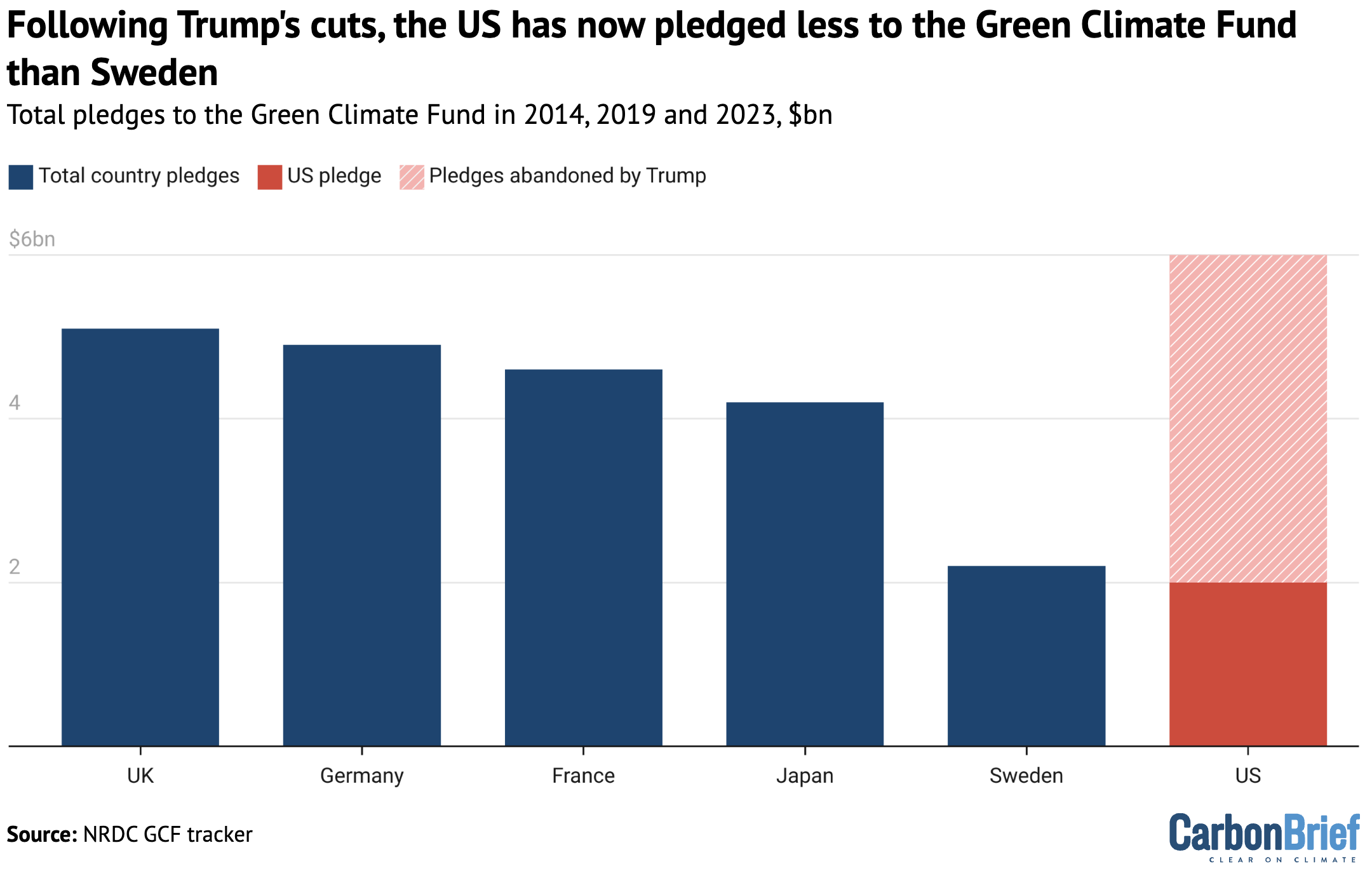

Such funding is also at risk as the new administration pulls away from what the White House calls “international agreements and initiatives that do not reflect our country’s values”. Notably, the US has now cancelled $4bn in funds previously committed to the GCF.

(Biden and Obama pledged $3bn each to the fund. However, neither of them ever delivered more than $1bn of their pledge, leaving $4bn outstanding.)

As the chart below shows, this means the US contribution to the GCF is now lower than that of Sweden – a country with an economy 50 times smaller.

The GCF is not the only specific fund that has been targeted. The US formally ended its involvement in the UN loss and damage fund, which it pledged $17.6m towards in 2023. It has also withdrawn from the Just Energy Transition Partnership initiative, which included at least $56m in grants to help South Africa transition away from coal power.

Another Trump executive order announced a review of “international intergovernmental organisation” membership, including MDBs.

There is an assumption that the US will not give up its considerable power in these banks. However, Trump supporters, including those behind the influential Project 2025, have laid out plans for withdrawing the US from the World Bank.

A large chunk of the remaining US climate finance in recent years has come from the US International Development Finance Corporation (DFC), which committed more than $3.7bn in climate finance in 2024 and a similar amount in 2023. This included loans for a wind power project in Mozambique and a railway to carry critical minerals through Angola.

DFC is a development finance institution that invests in private enterprises and was set up under the first Trump administration. It has so far been insulated from US aid cuts and there has been speculation that it may now play a larger role in US foreign policy.

Leaning more heavily on DFC, as well as the US Export-Import Bank (EXIM), would not be suitable for climate finance, Ritu Bharadwaj, a climate-finance principal researcher at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), tells Carbon Brief:

“If these mechanisms remain intact while grant-based finance is gutted, it signals a shift away from public, needs-based funding toward finance that prioritises US commercial and strategic interests. In other words, what little climate finance remains will likely benefit US corporations first, rather than frontline communities.”

Additionally, even if such organisations are favoured by the new administration, this does not mean their climate projects will be protected. Benjamin Black, Trump’s nominee to lead DFC, wrote a blog post about the corporation in January, stating:

“The Biden administration’s emphasis on virtue-signaling – such as dedicating 40% of [DFC’s] recent commitments to green projects – raises serious concerns.”

Carr tells Carbon Brief that more US climate spending could still end up on the “cutting block”:

“From what we’ve seen so far, it looks to me like they are going to try and root out everything that they see as clearly related to climate.”

He caveats this by noting that some of the money the Biden administration would have counted as climate finance may continue, but not be defined as such.

This highlights the importance of accounting when assessing climate finance. Different governments around the world report different things as climate finance, depending on their priorities and political leanings.

For example, during the last Trump presidency, the US stopped reporting on climate finance to the UN. When calculating progress towards the $100bn goal during this period, the OECD had to estimate US figures based on “provisional data” or averages from previous years.

The Biden administration retrospectively reported the missing data from the Trump years in 2021, resulting in the OECD scaling down a previous estimate.

Clemence Landers, a senior policy fellow at the Center for Global Development (CGD) who previously worked at the US Treasury, tells Carbon Brief that a “very educated guess [is] that there will be no reporting from the US” in the coming years.

The US government website tracking aid has not been updated since December.

If climate finance is not recorded, this could hamper its inclusion in the annual $100bn goal, which lasts until 2025, as well as the $300bn goal that countries agreed on last year at COP29 to replace it, as Landers notes:

“That does leave an enormous gulf in terms of the new global climate-finance target.”

Methodology

Climate-finance reporting practices mean that official data can be difficult to analyse in detail.

In this article, annual US climate-finance figures for the period 2015-2022 are based on those reported by the US government to the UN in biennial reports (BRs) and, for the years 2021 and 2022, its first biennial transparency report (BTR).

These can be considered “official” climate-finance figures. They align with the figures that the US federal government has released and are the ones used to inform the OECD’s assessments of developed countries’ progress towards the $100bn annual target.

The figures only include bilateral climate finance and inputs into multilateral climate funds. MDB shares and private finance mobilised are not covered. Again, this aligns with the “climate-finance” totals quoted in progress reports by the Biden administration.

The climate-finance totals for 2023 and 2024 are based on releases from the US Department of State during the Biden administration. These figures are for the US financial year (FY), which runs from 1 October to 30 September. However, the FY figures are the same as the calendar year numbers reported to the UN for 2021 and 2022, so Carbon Brief assumes the same is true for 2023 and 2024.

Due to the significant time lag in official reporting to the UN, the figures underpinning these totals are not due to be released until 2026. (The previous Trump administration did not report them at all and it is unlikely that the current one will either, now that the US has announced its departure from the Paris Agreement.)

Given this time lag, estimates for total international climate finance in 2023 and 2024 are derived from a joint analysis by the thinktanks Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), ODI, Germanwatch and ECCO. This calculated likely totals in 2030, based on existing pledges and planned reforms. Carbon Brief assumes a steady trajectory to the overall $197bn estimated under the thinktanks’ “business-as-usual” scenario, with bilateral finance, specifically, reaching $50bn by 2025.

Climate-finance figures reported to the UN by the US do not include details of the government departments and agencies responsible, making it difficult to determine the share overseen by USAid. The Biden administration also did not report the breakdown between agencies.

This data is reported to the OECD Creditor Reporting System (CRS), which contains figures up to 2023. However, the information in the CRS is not “official” climate finance, but rather “climate-related development finance”, identified as such using Rio Markers. Most countries apply simple coefficients to convert the figures they report to the CRS into their climate-finance submissions to the UN, but the US calculates its climate-finance submissions separately.

Nevertheless, to obtain approximate figures, Carbon Brief has assumed that 100% of CRS projects marked as “principal” climate projects and 50% of the projects marked as “significant”, are climate finance. This aligns with a methodology used by other organisations, such as Oxfam, as well as other nations, including Germany, Japan and Denmark.

However, it is only a rough estimate. Experts that Carbon Brief consulted stressed the uncertainties of climate finance reporting and said the numbers could be higher or lower.

The post Analysis: Nearly a tenth of global climate finance threatened by Trump aid cuts appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Nearly a tenth of global climate finance threatened by Trump aid cuts

Climate Change

Greenpeace organisations to appeal USD $345 million court judgment in Energy Transfer’s intimidation lawsuit

SYDNEY, Saturday 28 February 2026 — Greenpeace International and Greenpeace organisations in the US announce they will seek a new trial and, if necessary, appeal the decision with the North Dakota Supreme Court following a North Dakota District Court judgment today awarding Energy Transfer (ET) USD $345 million.

ET’s SLAPP suit remains a blatant attempt to silence free speech, erase Indigenous leadership of the Standing Rock movement, and punish solidarity with peaceful resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline. Greenpeace International will also continue to seek damages for ET’s bullying lawsuits under EU anti-SLAPP legislation in the Netherlands.

Mads Christensen, Greenpeace International Executive Director said: “Energy Transfer’s attempts to silence us are failing. Greenpeace International will continue to resist intimidation tactics. We will not be silenced. We will only get louder, joining our voices to those of our allies all around the world against the corporate polluters and billionaire oligarchs who prioritise profits over people and the planet.

“With hard-won freedoms under threat and the climate crisis accelerating, the stakes of this legal fight couldn’t be higher. Through appeals in the US and Greenpeace International’s groundbreaking anti-SLAPP case in the Netherlands, we are exploring every option to hold Energy Transfer accountable for multiple abusive lawsuits and show all power-hungry bullies that their attacks will only result in a stronger people-powered movement.”

The Court’s final judgment today rejects some of the jury verdict delivered in March 2025, but still awards hundreds of millions of dollars to ET without a sound basis in law. The Greenpeace defendants will continue to press their arguments that the US Constitution does not allow liability here, that ET did not present evidence to support its claims, that the Court admitted inflammatory and irrelevant evidence at trial and excluded other evidence supporting the defense, and that the jury pool in Mandan could not be impartial.[1][2]

ET’s back-to-back lawsuits against Greenpeace International and the US organisations Greenpeace USA (Greenpeace Inc.) and Greenpeace Fund are clear-cut examples of SLAPPs — lawsuits attempting to bury nonprofits and activists in legal fees, push them towards bankruptcy and ultimately silence dissent.[3] Greenpeace International, which is based in the Netherlands, is pursuing justice in Europe, with a suit against ET under Dutch law and the European Union’s new anti-SLAPP directive, a landmark test of the new legislation which could help set a powerful precedent against corporate bullying.[4]

Kate Smolski, Program Director at Greenpeace Australia Pacific, said: “This is part of a worrying trend globally: fossil fuel corporations are increasingly using litigation to attack and silence ordinary people and groups using the law to challenge their polluting operations — and we’re not immune to these tactics here in Australia.

“Rulings like this have a chilling effect on democracy and public interest litigation — we must unite against these silencing tactics as bad for Australians and bad for our democracy. Our movement is stronger than any corporate bully, and grows even stronger when under attack.”

Energy Transfer’s SLAPPs are part of a wave of abusive lawsuits filed by Big Oil companies like Shell, Total, and ENI against Greenpeace entities in recent years.[3] A couple of these cases have been successfully stopped in their tracks. This includes Greenpeace France successfully defeating TotalEnergies’ SLAPP on 28 March 2024, and Greenpeace UK and Greenpeace International forcing Shell to back down from its SLAPP on 10 December 2024.

-ENDS-

Images available in Greenpeace Media Library

Notes:

[1] The judgment entered by North Dakota District Court Judge Gion follows a jury verdict finding Greenpeace entities liable for more than US$660 million on March 19, 2025. Judge Gion subsequently threw out several items from the jury’s verdict, reducing the total damages to approximately US$345 million.

[2] Public statements from the independent Trial Monitoring Committee

[3] Energy Transfer’s first lawsuit was filed in federal court in 2017 under the RICO Act – the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, a US federal statute designed to prosecute mob activity. The case was dismissed in 2019, with the judge stating the evidence fell “far short” of what was needed to establish a RICO enterprise. The federal court did not decide on Energy Transfer’s claims based on state law, so Energy Transfer promptly filed a new case in a North Dakota state court with these and other state law claims.

[4] Greenpeace International sent a Notice of Liability to Energy Transfer on 23 July 2024, informing the pipeline giant of Greenpeace International’s intention to bring an anti-SLAPP lawsuit against the company in a Dutch Court. After Energy Transfer declined to accept liability on multiple occasions (September 2024, December 2024), Greenpeace International initiated the first test of the European Union’s anti-SLAPP Directive on 11 February 2025 by filing a lawsuit in Dutch court against Energy Transfer. The case was officially registered in the docket of the Court of Amsterdam on 2 July, 2025. Greenpeace International seeks to recover all damages and costs it has suffered as a result of Energy Transfers’s back-to-back, abusive lawsuits demanding hundreds of millions of dollars from Greenpeace International and the Greenpeace organisations in the US. The next hearing in the Court of Amsterdam is scheduled for 16 April, 2026.

Media contact:

Kate O’Callaghan on 0406 231 892 or kate.ocallaghan@greenpeace.org

Climate Change

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

The Trump administration’s relentless rollback of public health and environmental protections has allowed widespread toxic exposures to flourish, warn experts who helped implement safeguards now under assault.

In a new report that outlines a dozen high-risk pollutants given new life thanks to weakened, delayed or rescinded regulations, the Environmental Protection Network, a nonprofit, nonpartisan group of hundreds of former Environmental Protection Agency staff, warns that the EPA under President Donald Trump has abandoned the agency’s core mission of protecting people and the environment from preventable toxic exposures.

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

Climate Change

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

The country’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas benefited from what critics say is a questionable IRS interpretation of tax credits.

Cheniere Energy, the largest producer and exporter of U.S. liquefied natural gas, received $370 million from the IRS in the first quarter of 2026, a payout that shipping experts, tax specialists and a U.S. senator say the company never should have received.

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits