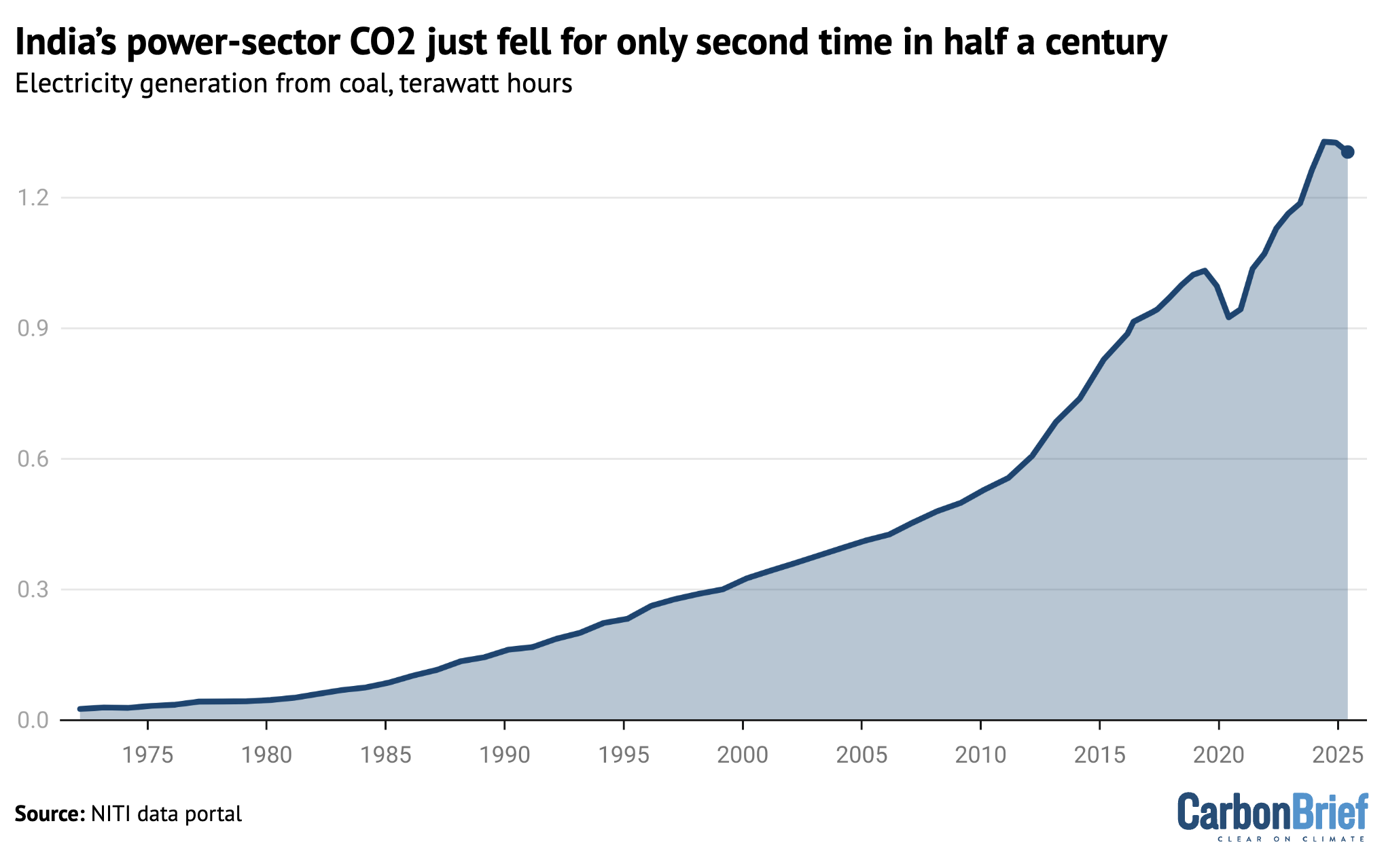

India’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from its power sector fell by 1% year-on-year in the first half of 2025 and by 0.2% over the past 12 months, only the second drop in almost half a century.

As a result, India’s CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and cement grew at their slowest rate in the first half of the year since 2001 – excluding Covid – according to new analysis for Carbon Brief.

The analysis is the first of a regular new series covering India’s CO2 emissions, based on monthly data for fuel use, industrial production and power output, compiled from numerous official sources.

(See the regular series on China’s CO2 emissions, which began in 2019.)

Other key findings on India for the first six months of 2025 include:

- The growth in clean-energy capacity reached a record 25.1 gigawatts (GW), up 69% year-on-year from what had, itself, been a record figure.

- This new clean-energy capacity is expected to generate nearly 50 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity per year, nearly sufficient to meet the average increase in demand overall.

- Slower economic expansion meant there was zero growth in demand for oil products, a marked fall from annual rates of 6% in 2023 and 4% in 2024.

- Government infrastructure spending helped accelerate CO2 emissions growth from steel and cement production, by 7% and 10%, respectively.

The analysis also shows that emissions from India’s power sector could peak before 2030, if clean-energy capacity and electricity demand grow as expected.

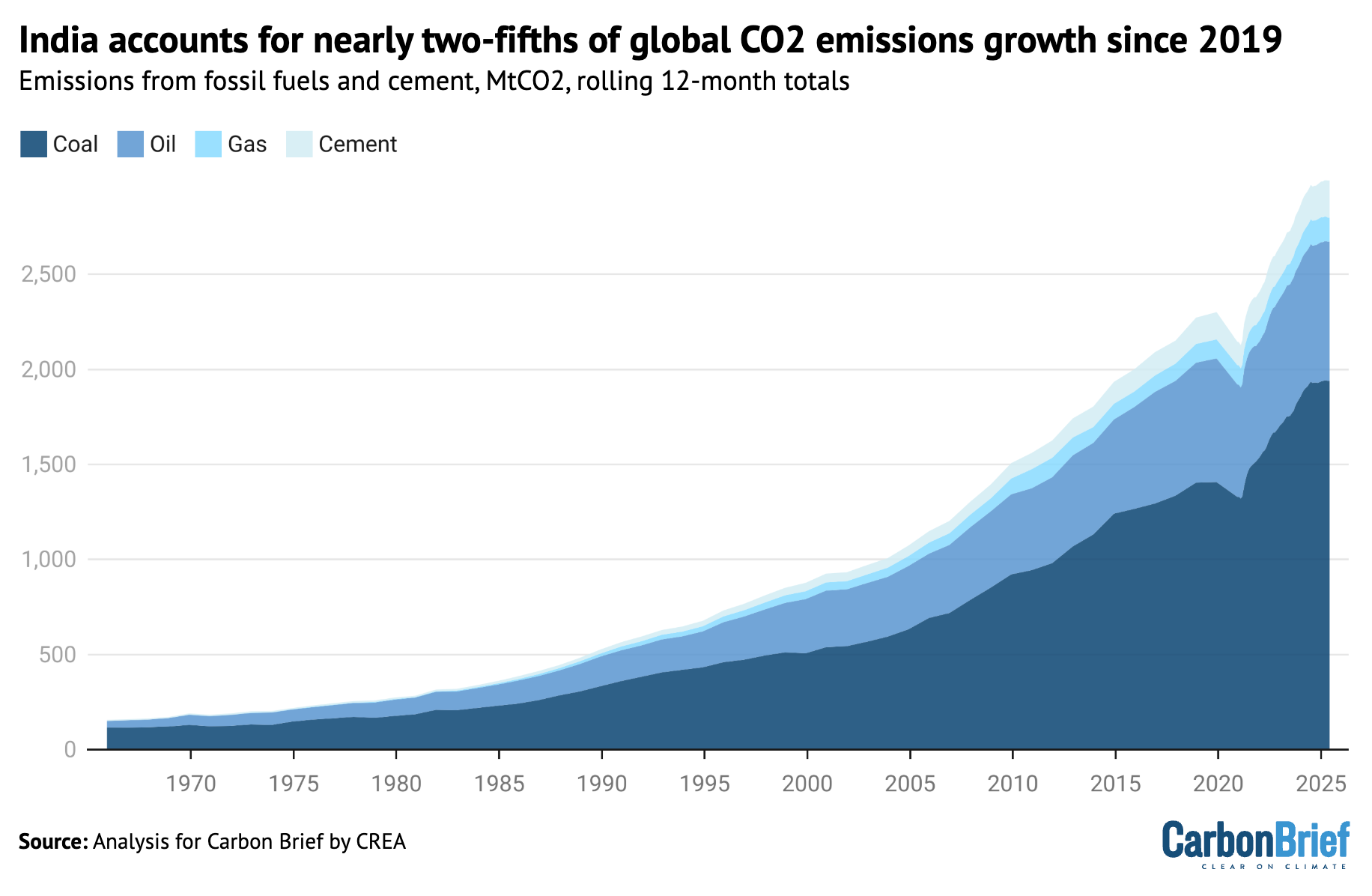

The future of CO2 emissions in India is a key indicator for the world, with the country – the world’s most populous – having contributed nearly two-fifths of the rise in global energy-sector emissions growth since 2019.

India’s surging emissions slow down

In 2024, India was responsible for 8% of global energy-sector CO2 emissions, despite being home to 18% of the world’s population, as its per-capita output is far below the world average.

However, emissions have been growing rapidly, as shown in the figure below.

The country contributed 31% of global energy-sector emissions growth in the decade to 2024, rising to 37% in the past five years, due to a surge in the three-year period from 2021-23.

More than half of India’s CO2 output comes from coal used for electricity and heat generation, making this sector the most important by far for the country’s emissions.

The second-largest sector is fossil fuel use in industry, which accounts for another quarter of the total, while oil use for transport makes up a further eighth of India’s emissions.

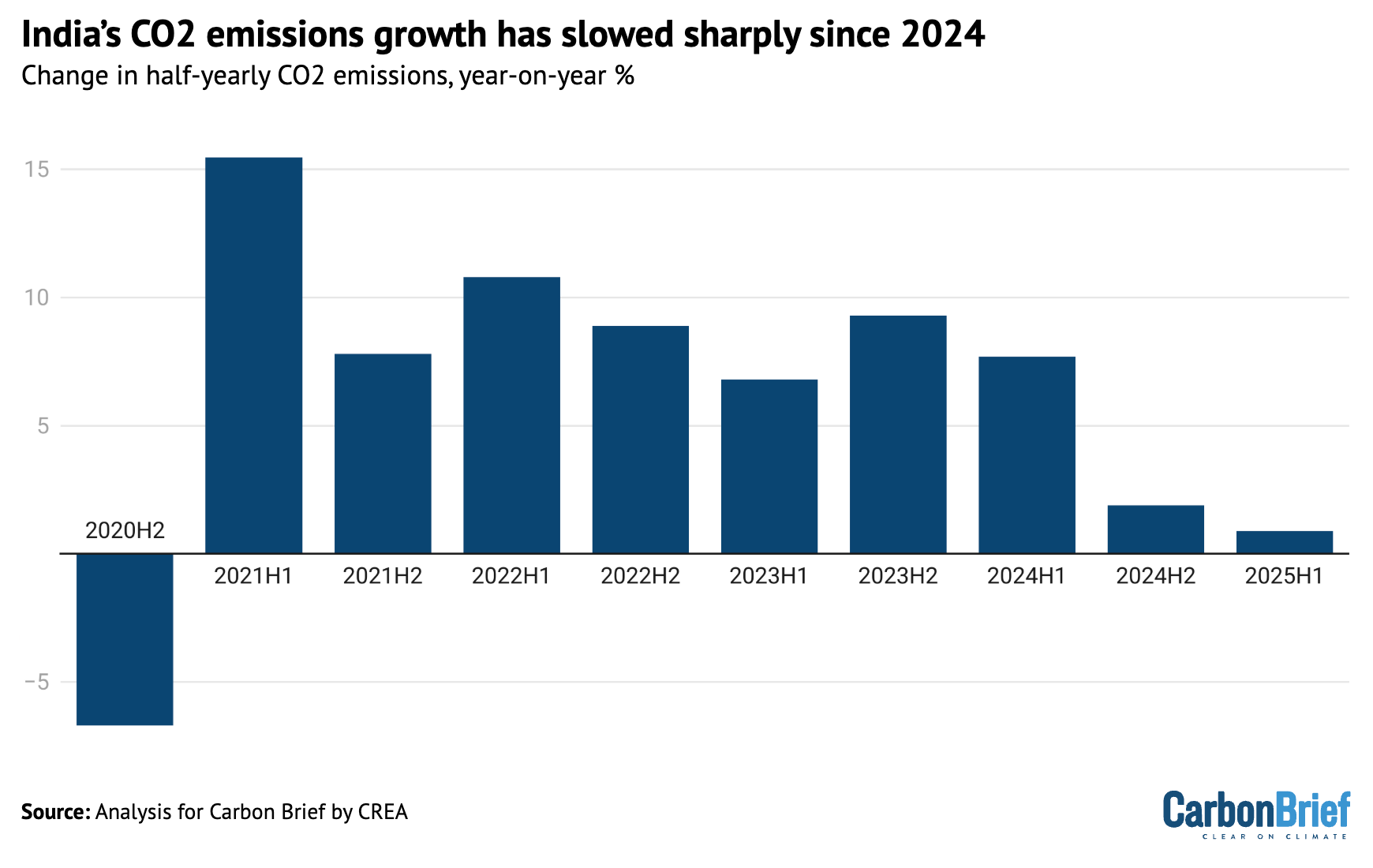

India’s CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and cement grew by 8% per year from 2019 to 2023, quickly rebounding from a 7% drop in 2020 due to Covid.

Before the Covid pandemic, emissions growth had averaged 4% per year from 2010 to 2019, but emissions in 2023 and 2024 rose above the pre-pandemic trendline.

This was despite a slower average GDP growth rate from 2019 to 2024 than in the preceding decade, indicating that the economy became more energy- and carbon-intensive. (For example, growth in steel and cement outpaced the overall rate of economic growth.)

A turnaround came in the second half of 2024, when emissions only increased by 2% year-on-year, slowing down to 1% in the first half of 2025, as seen in the figure below.

The largest contributor to the slowdown was the power sector, which was responsible for 60% of the drop in emissions growth rates, when comparing the first half of 2025 with the years 2021-23.

Oil demand growth slowed sharply as well, contributing 20% of the slowdown. The only sectors to keep growing their emissions in the first half of 2025 were steel and cement production.

Another 20% of the slowdown was due to a reduction in coal and gas use outside the power, steel and cement sectors. This comprises construction, industries such as paper, fertilisers, chemicals, brick kilns and textiles, as well as residential and commercial cooking, heating and hot water.

This is all shown in the figure below, which compares year-on-year changes in emissions during the second half of 2024 and the first half of 2025, with the average for 2021-23.

Power sector emissions fell by 1% in the first half of 2025, after growing 10% per year during 2021-23 and adding more than 50m tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) to India’s total every six months.

Oil product use saw zero growth in the first half of 2025, after rising 6% per year in 2021-23.

In contrast, emissions from coal burning for cement and steel production rose by 10% and 7%, respectively, while coal use outside of these sectors fell 2%.

Gas consumption fell 7% year-on-year, with reductions across the power and industrial sectors as well as other users. This was a sharp reversal of the 5% average annual growth in 2021-23.

Power-sector emissions pause

The most striking shift in India’s sectoral emissions trends has come in the power sector, where coal consumption and CO2 emissions fell 0.2% in the 12 months to June and 1% in the first half of 2025, marking just the second drop in half a century, as shown in the figure below.

The reduction in coal use comes after more than a decade of break-neck growth, starting in the early 2010s and only interrupted by Covid in 2020. It also comes even as the country plans large amounts of new coal-fired generating capacity.

In the first half of 2025, total power generation increased by 9 terawatt hours (TWh) year-on-year, but fossil power generation fell by 29TWh, as output from solar grew 17TWh, from wind 9TWh, from hydropower by 9TWh and from nuclear by 3TWh.

Analysis of government data shows that 65% of the fall in fossil-fuel generation can be attributed to lower electricity demand growth, 20% to faster growth in non-hydro clean power and the remaining 15% to higher output at existing hydropower plants.

Slower growth in electricity usage was largely due to relatively mild temperatures and high rainfall, in contrast to the heatwaves of 2024. A slowdown in industrial sectors in the second quarter of the year also contributed.

In addition, increased rainfall drove the jump in hydropower generation. India received 42% above-normal rainfall from March to May 2025. (In early 2024, India’s hydro output had fallen steeply as a result of “erratic rainfall”.)

Lower temperatures and this abundant rainfall reduced the need for air conditioning, which is responsible for around 10% of the country’s total power demand. In the same period in 2024, demand surged due to record heatwaves and higher temperatures across the country.

The growth in clean-power generation was buoyed by the addition of a record 25.1GW of non-fossil capacity in the first half of 2025. This was a 69% increase compared with the previous period in 2024, which had also set a record.

Solar continues to dominate new installations, with 14.3GW of capacity added in the first half of the year coming from large scale solar projects and 3.2GW from solar rooftops.

Solar is also adding the majority of new clean-power output. Taking into account the average capacity factor of each technology, solar power delivered 62% of the additional annual generation, hydropower 16%, wind 13% and nuclear power 8%.

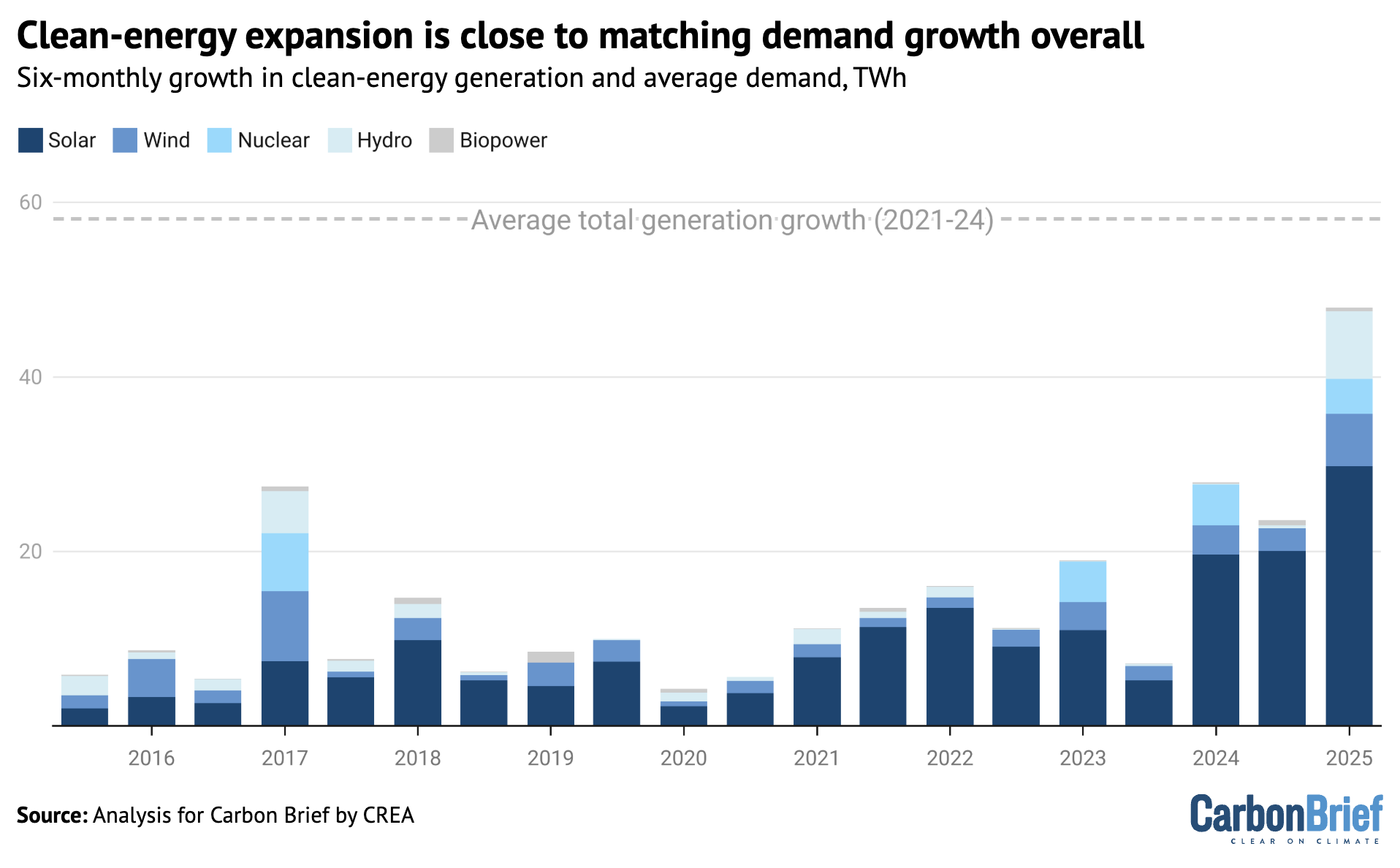

The new clean-energy capacity added in the first half of 2025 will generate record amounts of clean power. As shown in the figure below, the 50TWh per year from this new clean capacity is approaching the average growth of total power generation.

(When clean-energy growth exceeds total demand growth, generation from fossil fuels declines.)

India is expected to add another 16-17GW of solar and wind in the second half of 2025. Beyond this year, strong continued clean-energy growth is expected, towards India’s target for 500GW of non-fossil fuel capacity by 2030 (see below).

Slowing oil demand growth

The first half of 2025 also saw a significant slowdown in India’s oil demand growth. After rising by 6% a year in the three years to 2023, it slowed to 4% in 2024 and zero in the first half of 2025.

The slowdown in oil consumption overall was predominantly due to slower growth in demand for diesel and “other oil products”, which includes bitumen.

In the first quarter of 2025, diesel demand actually fell, due to a decline in industrial activity, limited weather-related mobility and – reportedly – higher uptake of vehicles that run on compressed natural gas (CNG), as well as electricity (EVs).

Diesel demand growth increased in March to May, but again declined in June because of early and unusually severe monsoon rains in India, leading to a slowdown in industrial and mining activities, disrupted supply-chains and transport of raw material, goods and services.

The severe rains also slowed down road construction activity, which in turn curtailed demand for transportation, construction equipment and bitumen.

Weaker diesel demand growth in 2024 had reflected slower growth in economic activity, as growth rates in the industrial and agricultural sectors contracted compared to previous years.

Another important trend is that EVs are also cutting into diesel demand in the commercial vehicles segment, although this is not yet a significant factor in the overall picture.

EV adoption is particularly notable in major metropolitan cities and other rapidly emerging urban centres and in the logistics sector, where they are being preferred for short haul rides over diesel vans or light commercial vehicles.

EVs accounted for only 7.6% of total vehicle sales in the financial year 2024-25, up 22.5% year-on-year, but still far from the target of 30% by 2030.

However, any significant drop in diesel demand will be a function of adoption of EV for long-haul trucks, which account for 32% of the total CO2 emissions from the transport sector. Only 280 electric trucks were sold in 2024, reported NITI Aayog.

Trucks remain the largest diesel consumers. Moreover, truck sales grew 9.2% year-on-year in the second quarter of 2025, driven in part by India’s target of 75% farm mechanisation by 2047. This sales growth may outweigh the reduction in diesel demand due to EVs. Subsidies for electric tractors have seen some pilots, but demand is yet to take off.

Apart from diesel, petrol demand growth continued in the first half of 2025 at the same rate as in earlier years. Modest year-on-year growth of 1.3% in passenger vehicle sales could temper future increases in petrol demand, however. This is a sharp decline from 7.5% and 10% growth rates in sales in the same period in 2024 and 2023.

Furthermore, EVs are proving to be cheaper to run than petrol for two- and three-wheelers, which may reduce the sale of petrol vehicles in cities that show policy support for EV adoption.

Steel and cement emissions continue to grow

As already noted, steel and cement were the only major sectors of India’s economy to see an increase in emissions growth in the first half of 2025.

While they were only responsible for around 12% of India’s total CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and cement in 2024, they have been growing quickly, averaging 6% a year for the past five years.

The growth in emissions accelerated in the first half of 2025, as cement output rose 10% and steel output 7%, far in excess of the growth in economic output overall.

Steel and cement growth accelerated further in July. A key demand driver is government infrastructure spending, which tripled from 2019 to 2024.

In the second quarter of 2025, the government’s capital expenditure increased 52% year-on-year. albeit from a low base during last year’s elections. This signals strong growth in infrastructure.

The government is targeting domestic steel manufacturing capacity of 300m tonnes (Mt) per year by 2030, from 200Mt currently, under the National Steel Policy 2017, supported by financial incentives for firms that meet production targets for high quality steel.

The government also imposed tariffs on steel imports in April and stricter quality standards for imports in June, in order to boost domestic production.

Government policies such as Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojna – a “housing for all” initiative under which 30m houses are to be built by FY30 – is further expected to lift demand for steel and cement.

The automotive sector in India is expected to grow at a fast pace, with sales expected to reach 7.5m units for passenger vehicle and commercial vehicle segments from 5.1m units in 2023, in addition to rapid growth in electric vehicles. This can be expected to be another key driver for growth of the steel sector, as 900 kg of steel is used per vehicle.

Without stringent energy efficiency measures and the adoption of cleaner fuel, the expected growth in steel and cement production could drive significant emissions growth from the sector.

Power-sector emissions could peak before 2030

Looking beyond this year, the analysis shows that CO2 from India’s power sector could peak before 2030, having previously been the main driver of emissions growth.

To date, India’s clean-energy additions have been lagging behind the growth in total electricity demand, meaning fossil-fuel demand and emissions from the sector have continued to rise.

However, this dynamic looks likely to change. In 2021, India set a target of having 500GW of non-fossil power generation capacity in place by 2030. Progress was slow at first, so meeting the target implies a substantial acceleration in clean-energy additions.

The country has been laying the groundwork for such an acceleration.

There was 234GW of renewable capacity in the pipeline as of April 2025, according to the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy. This includes 169GW already awarded contracts, of which 145GW is under construction, and an additional 65GW put out to tender. There is also 5.2GW of new nuclear capacity under construction.

If all of this is commissioned by 2030, then total non-fossil capacity would increase to 482GW, from 243GW at the end of June 2025, leaving a gap of just 18GW to be filled with new projects.

When the non-fossil capacity target was set in 2021, CREA assessed that the target would suffice to peak demand for coal in power generation before 2030. This assessment remains valid and is reinforced by the latest Central Electricity Authority (CEA) projection for the country’s “optimal power mix” in 2030, shown in the figure below.

In the CEA’s projection, the share of non-fossil power generation rises to 44% in the 2029-30 fiscal year, up from 25% in 2024-25. From 2025 to 2030, power demand growth, averaging 6% per year, is entirely covered from clean sources.

To accomplish this, the growth in non-fossil power generation would need to accelerate over time, meaning that towards the end of the decade, the growth in clean power supply would clearly outstrip demand growth overall – and so power generation from fossil fuels would fall.

While coal-power generation is expected to flatline, large amounts of new coal-power capacity is still being planned, because of the expected growth in peak electricity demand.

The post-Covid increase in electricity demand has given rise to a wave of new coal power plant proposals. Recent plans from the government target an increase in coal-power capacity by another 80-100GW by 2030-32, with 35GW already under construction as of July 2025.

The rationale for this is the increase in peak electricity loads, associated in particular with worsening heatwaves and growing use of air conditioning. The increase might yet prove unneeded.

Analysis by CREA shows that solar and wind are making an increasing contribution to meeting peak loads. This contribution will increase with the roll-out of solar power with integrated battery storage, the cost of which fell by 50-60% from 2023 to 2025.

The latest auction held in India saw solar power with battery storage bidding at prices, per unit of electricity generation, that were lower than the cost of new coal power.

This creates the opportunity to accelerate the decarbonisation of India’s power sector, by reducing the need for thermal power capacity.

The clean-energy buildout has made it possible for India to peak its power-sector emissions within the next few years, if contracted projects are built, clean-energy growth is maintained or accelerated beyond 2030 and demand growth remains within the government’s projections.

This would be a major turning point, as the power sector has been responsible for half of India’s recent emissions growth. In order to peak its emissions overall, however, India would still need to take further action to address CO2 from industry and transport.

With the end-of-September 2025 deadline nearing, India has yet to publish its international climate pledge (nationally determined contribution, NDC) for 2035 under the Paris Agreement, meaning its future emissions path, in the decades up to its 2070 net-zero goal, remains particularly uncertain.

The country is expected to easily surpass the headline climate target from its previous NDC, of cutting the emissions intensity of its economy to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030. As such, this goal is “unlikely to drive real world emission reductions”, according to Climate Action Tracker.

In July of this year, it met a 2030 target for 50% of installed power generating capacity to be from non-fossil sources, five years early.

About the data

This analysis is based on official monthly data for fuel consumption, industrial production and power generation from different ministries and government institutes.

Coal consumption in thermal power plants is taken from the monthly reports downloaded from the National Power Portal of the Ministry of Power. The data is compiled for the period January 2019 until June 2025. Power generation and capacity by technology and fuel on a monthly basis are sourced from the NITI data portal.

Coal use at steel and cement plants, as well as process emissions from cement production, are estimated using production indices from the Index of Eight Core Industries released monthly by the Office of Economic Adviser, assuming that changes in emissions follow production volumes.

These production indices were used to scale coal use by the sectors in 2022. To form a basis for using the indices, monthly coal consumption data for 2022 was constructed for the sectors using the annual total coal consumption reported in IEA World Energy Balances and monthly production data in a paper by Robbie Andrew, on monthly CO2 emission accounting for India.

Annual cement process emissions up to 2024 were also taken from Robbie Andrew’s work and scaled using the production indices. This approach better approximated changes in energy use and emissions reported in the IEA World Energy Balances, than did the amounts of coal reported to have been dispatched to the sectors, showing that production volumes are the dominant driver of short-term changes in emissions.

For other sectors, including aluminium, auto, chemical and petrochemical, paper and plywood, pharmaceutical, graphite electrode, sugar, textile, mining, traders and others, coal consumption is estimated based on data on despatch of domestic and imported coal to end users from statistical reports and monthly reports by the Ministry of Coal, as consumption data is not available.

The difference between consumption and dispatch is stock changes, which are estimated by assuming that the changes in coal inventories at end user facilities mirror those at coal mines, with end user inventories excluding power, steel and cement assumed to be 70% of those at coal mines, based on comparisons between our data and the IEA World Energy Balances.

Stock changes at mines are estimated as the difference between production at and despatch from coal mines, as reported by the Ministry of Coal.

In the case of the second quarter of the year 2025, data on domestic coal has been taken from the monthly reports by the Ministry of Coal. The regular data releases on coal imports have not taken place for the second quarter of 2025, for unknown reasons, so data was taken from commercial data providers Coal Hub and mjunction services ltd.

Product-wise petroleum product consumption data, as well as gas use by sector, was downloaded from the Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell of the Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas.

As the fuel dispatch and consumption data is reported as physical volumes, calorific values are taken from IEA’s World Energy Balance and CO2 emission factors from 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories.

Calorific values are assigned separately to different fuel types, including domestic and imported coal, anthracite and coke, as well as petrol, diesel and several other oil products.

The post Analysis: India’s power-sector CO2 falls for only second time in half a century appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: India’s power-sector CO2 falls for only second time in half a century

Greenhouse Gases

Guest post: How the Greenland ice sheet fared in 2025

Greenland is closing in on three decades of continuous annual ice loss, with 1995-96 being the last year in which the giant ice sheet grew in size.

With another melt season over, Greenland lost 105bn tonnes of ice in 2024-25.

The past year has seen some notable events, including ongoing ice melt into the month of September – well beyond the end of August when Greenland’s short summer typically draws to a close.

In a hypothetical world not impacted by human-caused climate change, ice melt in Greenland would rarely occur in September – and, if it did, it would generally be confined to the south.

In this article, we explore how Greenland’s ice sheets fared over the 12 months to August 2025, including the evidence that the territory’s summer melting season is lengthening.

(For our previous analyses of Greenland’s ice cover, see coverage in 2024, 2023, 2022, 2021, 2020, 2019, 2018, 2017, 2016 and 2015.)

Surface mass balance

The seasons in Greenland are overwhelmingly dominated by winter.

The bitterly cold, dark winter lasts up to ten months, depending on where you are. In contrast, the summer period is generally rather short, starting in late May in southern Greenland and in June in the north, before ending in late August.

Greenland’s annual ice cycle is typically measured from 1 September through to the end of August.

This is because the ice sheet largely gains snow on the surface from September, accumulating ice through autumn, winter and into spring.

Then, as temperatures increase, the ice sheet begins to lose more ice through surface melt than it gains from snowfall, generally from mid-June. The melt season usually continues until the middle or end of August.

Over this 12-month period, scientists track the “surface mass balance” (SMB) of the ice sheet. This is the balance between ice gains and losses at the surface.

To calculate ice gain and losses, scientists use data collected by high-resolution regional climate models and Sentinel satellites.

The SMB does not consider all ice losses from Greenland – we will come to that later – but instead provides a gauge of changes at the surface of the ice sheet.

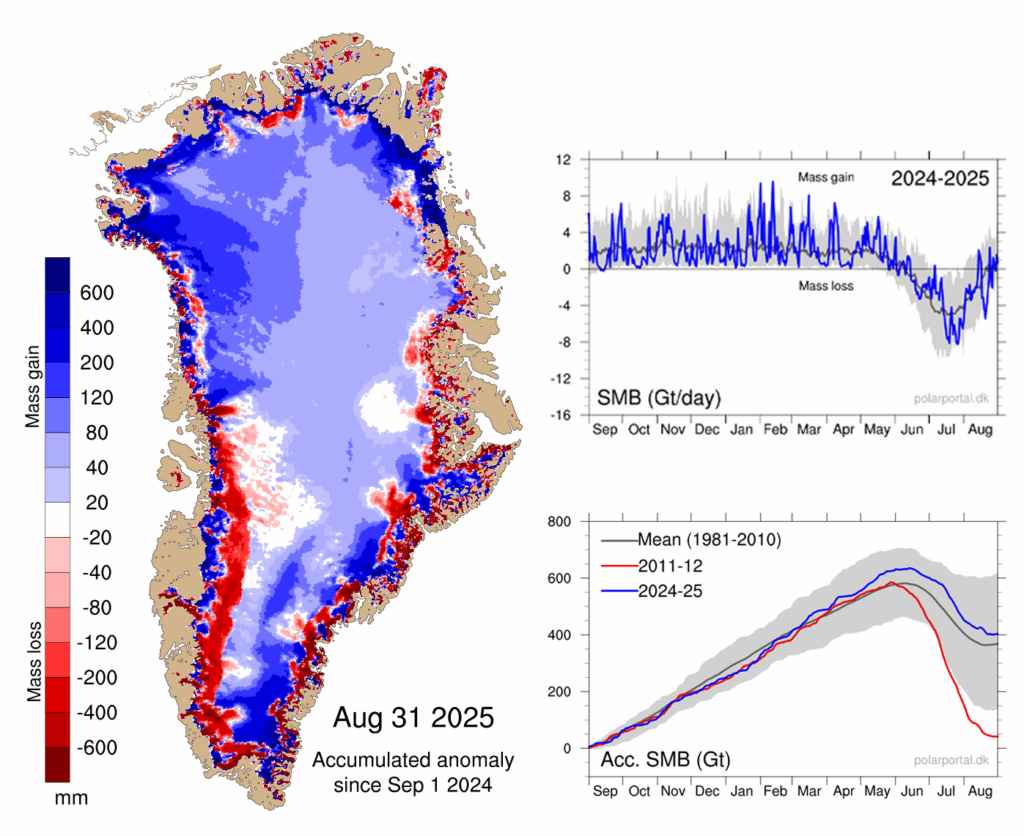

According to our calculations, Greenland ended the year 2024-25 with an overall SMB of about 404bn tonnes. This is the 15th highest SMB in a dataset that goes back 45 years, exceeding the 1981-2010 average by roughly 70bn tonnes.

This year’s SMB is illustrated in the maps and charts below, based on data from the Polar Portal.

The blue line in the upper chart shows the day-to-day SMB. Large snowfall events become visible as “spikes”. The blue line in the lower chart depicts the accumulated SMB since 1 September 2024. In grey, the long-term average and its variability are shown. For comparison, the red line shows the record-low year of 2011-12.

The map shows the geographic spread of SMB gains (blue) and losses (red) for 2024-25, compared to the long-term average.

It illustrates that southern and north-western Greenland had a relatively wet year compared to the long-term average, while there was mass loss along large sections of the coast, in particular in the south-west. The spikes of snow and melt are clearly visible in the graphs on the right.

Lengthening summer

Scientists have traditionally pinned the start of the “mass balance year” in Greenland to 1 September, given that this is when the ice sheet typically starts to gain mass.

However, evidence has started to emerge of a lengthening of the summer season in Greenland – as predicted some time ago by climate models.

The start of the 2024-25 mass balance year in Greenland saw ice melt continuing into September. This included a particularly unusual spike in ice melt in the northern part of the territory in September as well as all down the west coast.

In a world without human-caused climate change, ice melt in September would be very rare – and generally confined to the south.

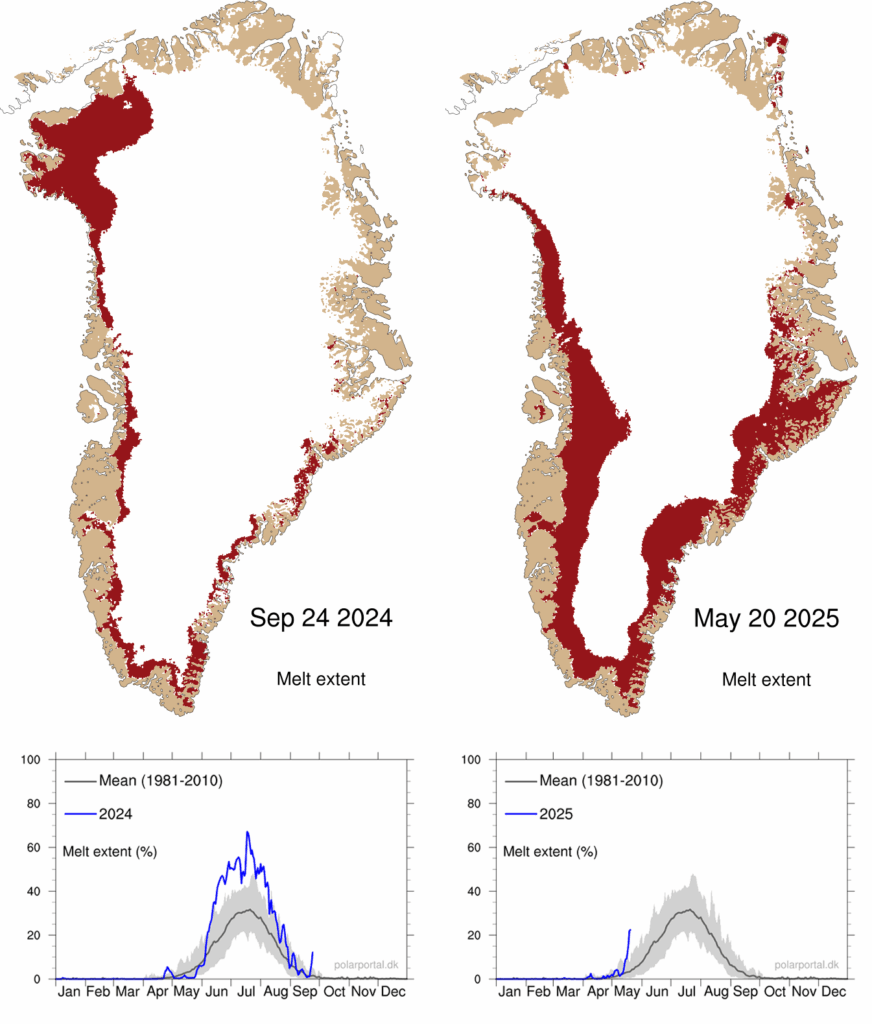

Greenland also saw an early start to the summer melt season in 2025. The onset of the melting season, defined as the first of at least three days in a row with melting over more than 5% of the ice sheet, was on 14 May. This is 12 days earlier than the 1981-2025 average.

The maps below show the extent of melt (red shading) across the ice sheet on 24 September 2024 (left) and 20 May 2025 (right). The blue lines in charts beneath show the percentage melt in 2024 (left) and 2025 (right), up to these dates, compared to the 1981-2010 average (grey).

The melt season began with a significant spike of melting across the southern part of the ice sheet. This happened in combination with sea ice breaking up particularly early in north-west Greenland, allowing the traditional narwhal hunt to start much earlier than usual.

Surface melt

The ablation season, which covers the period in the year when Greenland is losing ice, started a little late. The onset of the season – defined as the first of at least three days in a row with an SMB below -1bn tonnes – began on 15 June, which is two days later than the 1981-2010 average.

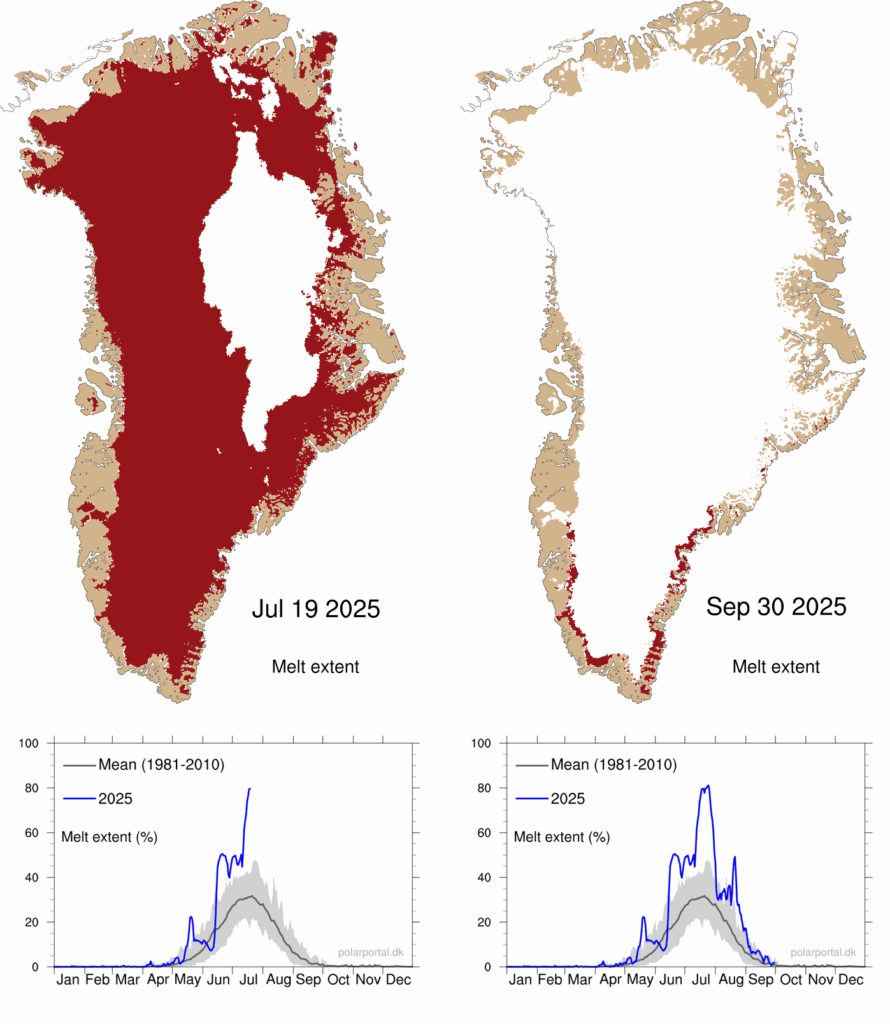

Overall, during the 2025 summer, a remarkably large percentage of the ice sheet was melting at once. This area was larger than the 1981-2010 average for three and a half months (mid-June to end of September).

In mid-July, melting occurred over a record area. For three days in a row, melting was present over more than 80% of the area of the ice sheet – peaking at 81.2%. This is the highest value in our dataset, which started in 1981.

The red shading in the maps below shows the extent of melting across Greenland on 19 July (left) and 30 September (right) 2025. The charts beneath show the daily extent of melting through 2025 (blue line), up to these dates, compared to the 1981-2010 average.

Snowfall

However, the SMB is not just about ice melt.

There was a lack of snowfall in the early winter months (September to January), particularly in south-east Greenland, which is typically the wettest part of the territory. The months that followed then saw abundant snow, which brought snowfall totals up closer to average by the start of summer.

A cold period at the end of May and in June protected the ice sheet from excessive ice loss. Melt then continued rather weakly until mid-July.

This was followed by strong melting rates in the second half of July and again in mid-August.

Overall, with both ice melt and snowfall exceeding their historical averages for the year as a whole, the SMB of the Greenland ice sheet ended above the 1981-2010 average.

These increases in snowfall and melt are in line with what scientists expect in a warming climate. This is because air holds more water vapour as it warms – leading to more snowfall and rain. Warmer temperatures also lead to more ice melt.

Total mass balance

The surface mass balance is just one component of the “total” mass balance (TMB) of the Greenland ice sheet.

The total mass balance of Greenland is the sum of the SMB, the marine mass balance (MMB) and basal mass balance (BMB). In other words, it brings together calculations from the surface, sides and base of the ice sheet.

The MMB measures the impact of the breaking off – or “calving” – of icebergs, as well as the melting of the front of glaciers where they meet the warm sea water. The MMB is always negative and has increased towards more negative values over the last decades.

BMB refers to ice losses from the base of the ice sheet. This makes a small negative contribution to the TMB.

(The only way for the ice sheet to gain mass is through snowfall.)

The continued mass loss observed in Greenland is primarily due to a weakening of the SMB – caused by rising melt combined with insufficient compensation of lost ice through snowfall.

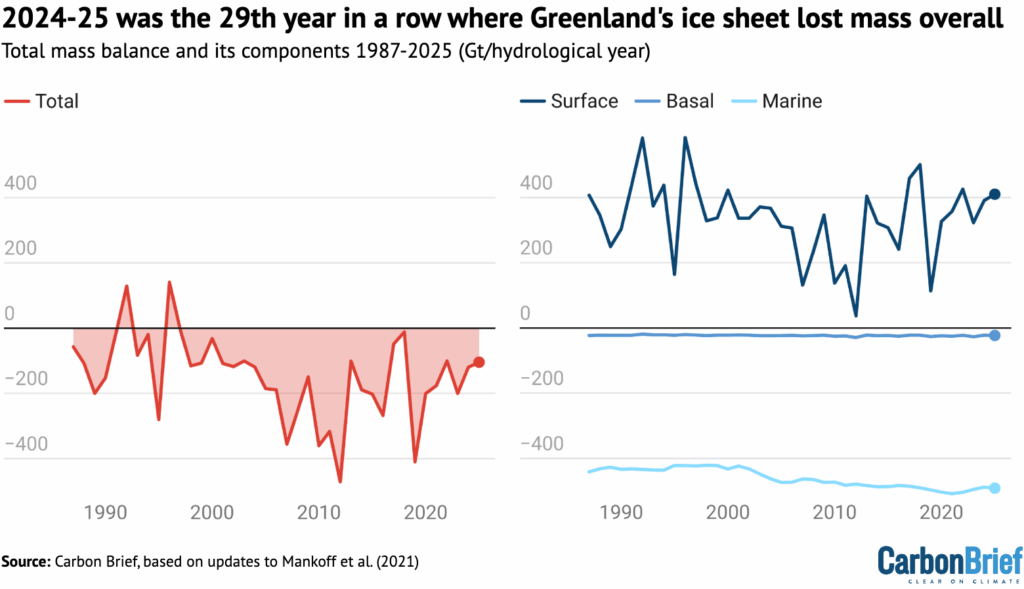

The figure below shows how much ice the Greenland ice sheet has lost (red) going back to 1987, which includes the SMB (dark blue), MMB (mid blue) and BMB (light blue). The analysis, which uses data from three models, is based on 2021 research published in Earth System Science.

Despite a relatively high SMB, high calving rates meant that Greenland lost 105bn tonnes of ice over the 12-month period.

This means that 2024-25 was the 29th year in a row with a Greenland ice sheet overall mass loss. As the chart shows, Greenland last saw an annual net gain of ice in 1996.

Satellite data

The mass balance of the Greenland ice sheet can also be measured by looking at the Earth’s gravitational field, using data captured by the Grace and Grace-FO satellite missions – a joint initiative from NASA and the German Aerospace Center.

The Grace satellites are twin satellites that follow each other closely at a distance of about 220km, which is why they are nicknamed “Tom and Jerry”. The distance between the two depends on gravity – which is, in turn, related to changes in mass on Earth, including ice loss.

Therefore, the distance between the two satellites, which can be measured very precisely, can be used to calculate loss of mass from the Greenland ice sheet.

Overall, the satellite data reveals that Greenland’s ice sheet lost around 55bn tonnes of ice over the 2024-25 season.

There is reasonably good agreement between the Grace satellite data and the model data, which, as noted above, finds that 105bn tonnes of ice was lost in Greenland over the same period.

However, the alignment of the two datasets – which are fully independent of each other – becomes more clear once a longer time period is considered.

In the 22-year period between April 2002 and May 2024, the Grace data shows that Greenland lost 4,911bn tonnes of ice. The modelling approach, on the other hand, calculates that 4,766bn tonnes of ice was lost.

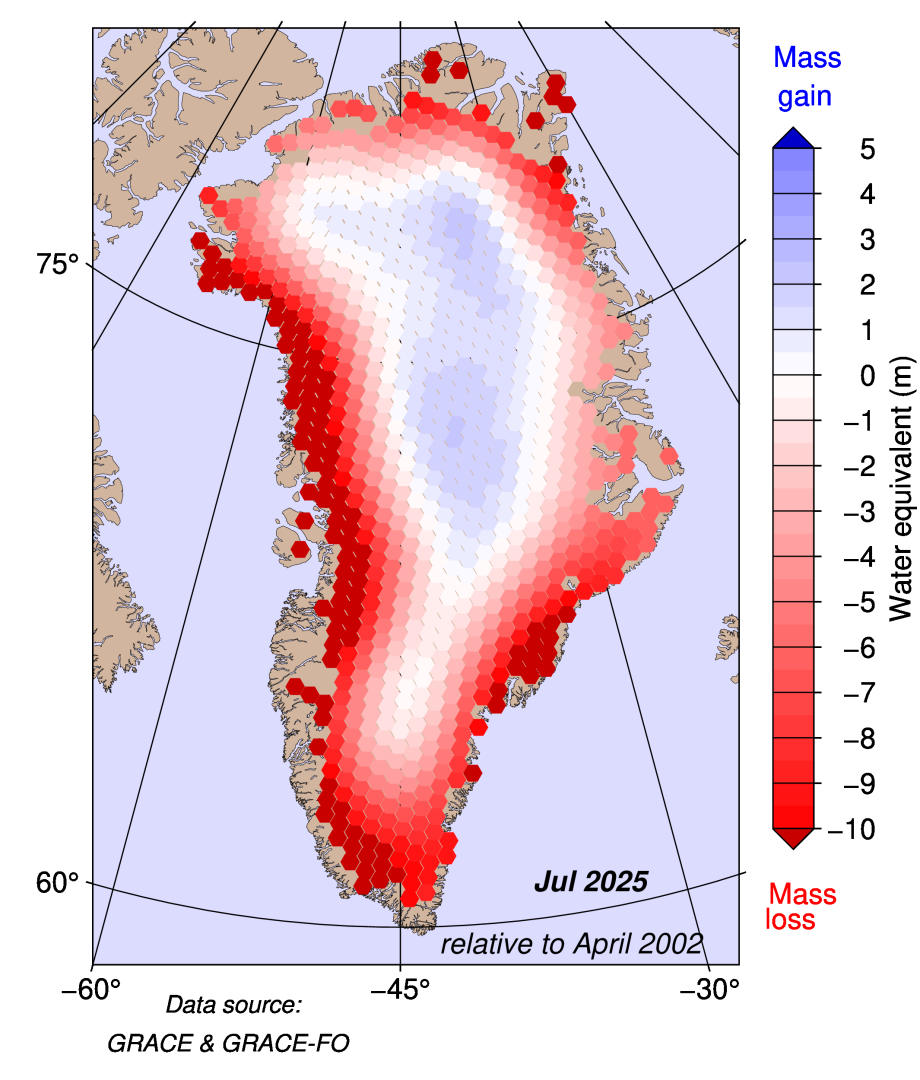

The figure below shows gain and loss in the total mass of ice of the Greenland ice sheet, calculated using Grace satellite measurements. It reveals that, over the past 23 years, there has been mass loss in the order of several metres along the coasts of Greenland, with the most significant losses seen on the western coast. Over the central parts of the ice sheet, there has been a small mass gain.

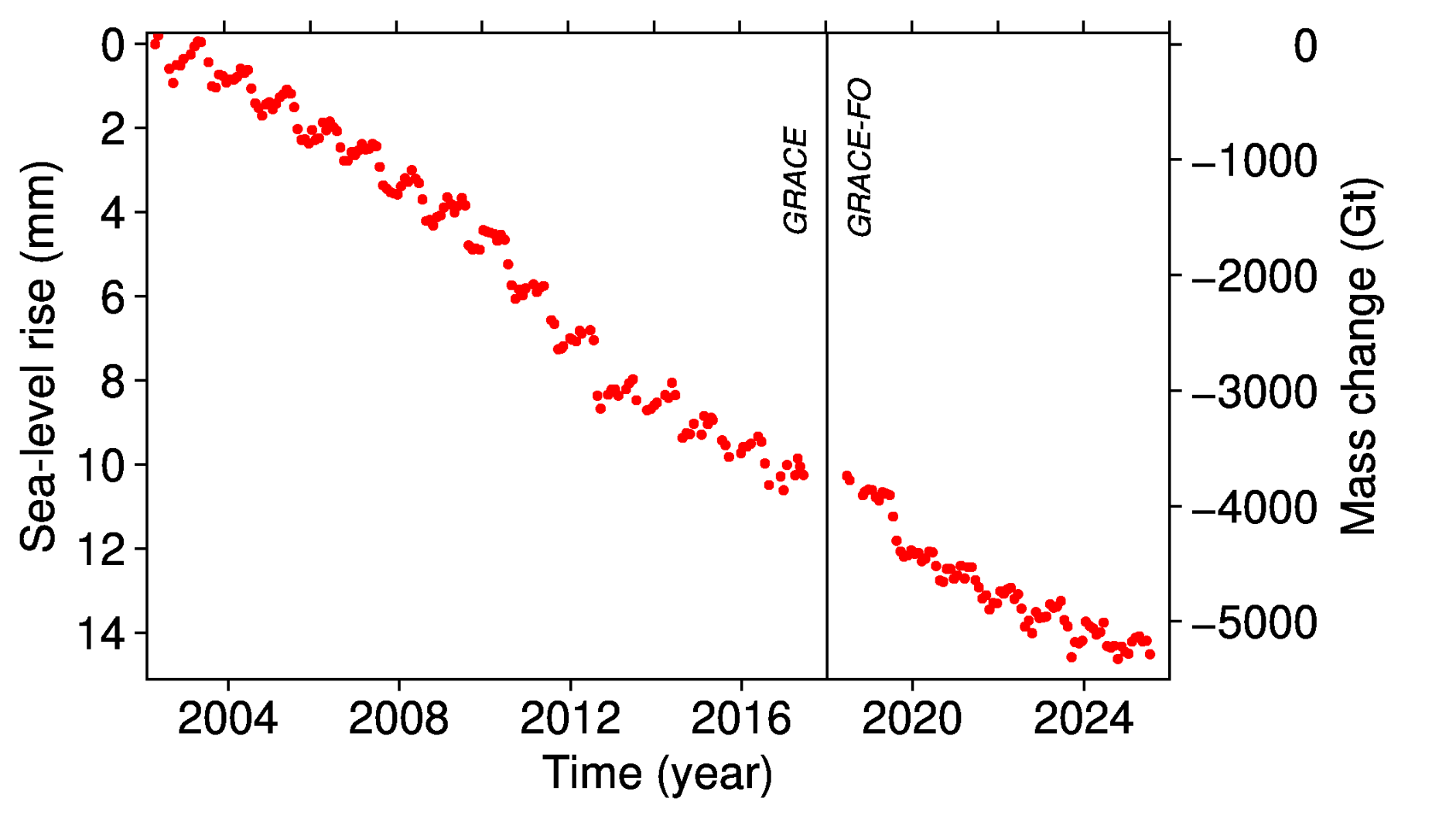

The lower figure shows the contribution of Greenland mass change to sea level rise over the last 23 years, according to the satellite data. It illustrates that more than 5,000bn tonnes of ice have been lost over the time period – contributing to roughly 1.5cm of sea level rise.

Warm over Europe and North America, cool over Greenland

As always, the weather systems across the northern hemisphere play a key role in the melt and snowfall that Greenland sees each year.

As in previous years, multiple heatwaves were observed in southern Europe and North America over the summer of 2025.

And, just like in 2024, there was only modest heat in northern Europe – with the notable exception of Arctic Scandinavia – with a comparably cool and rainy July followed by a warmer and sunnier August.

The high-pressure weather systems that bring heatwaves have a wide-ranging impact on weather extremes across the northern hemisphere.

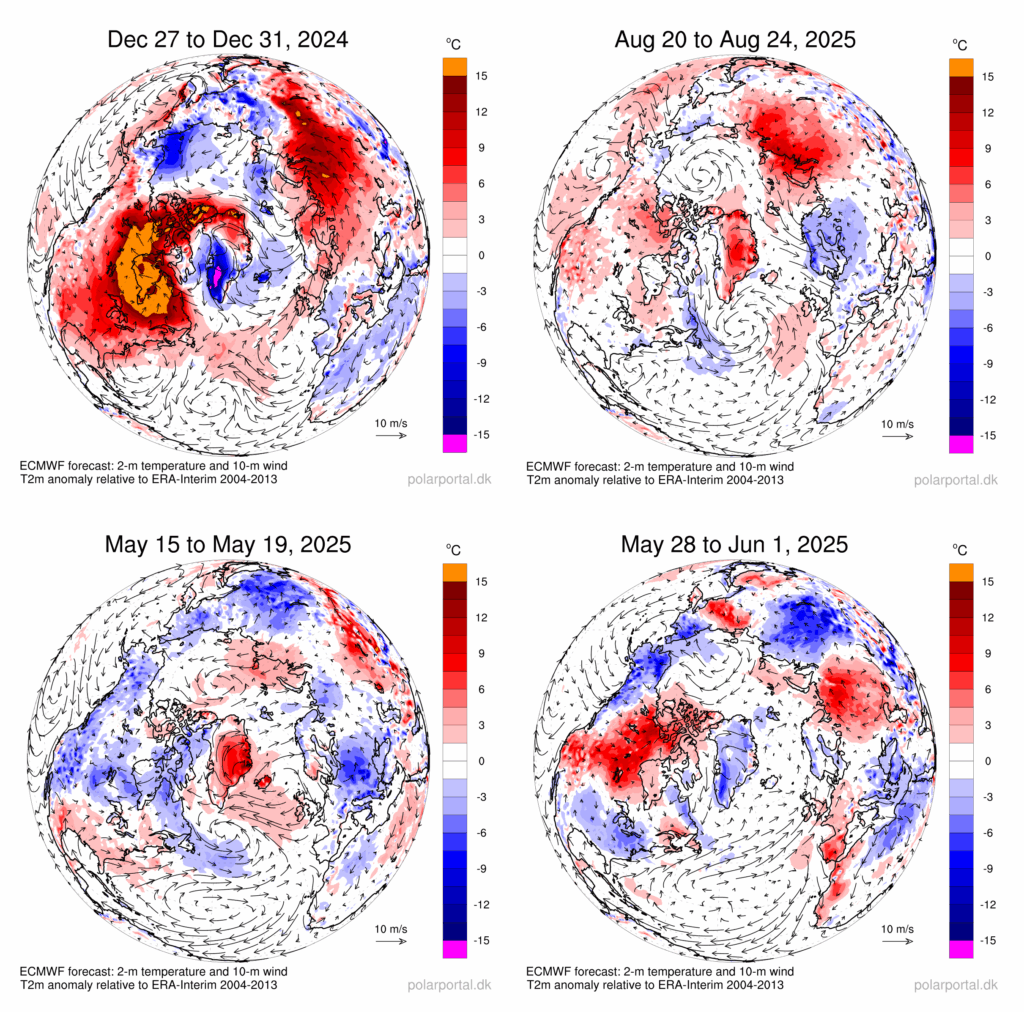

Strong blocking patterns over North America and Europe were repeatedly present in the course of the summer of 2025. In such a blocked flow, the jet stream – fast-moving winds that blow from west to east high in the atmosphere – is shaped like the Greek capital letter Omega (Ω).

The jet stream bulged up to the north over Canada and northern Europe. West and east of these ridges, low pressure troughs were found at both “feet” of the Omega. One of these troughs was located over Greenland (top left panel in next figure).

This resulted in widespread heat near the cores of these high-pressure systems, fuelling fires in several countries, including large wildfires in Canada. Smoke from these wildfires reached Greenland and Europe in late May.

Unlike in previous years, no heavy precipitation events were observed near the “feet” of the Omega.

If the Omega pattern is displaced by half a wavelength, the opposite – warm over Greenland, with cool continents – is also possible.

This circulation pattern occurred in August 2025 and is shown in the top right panel of the figure below. The bottom panel depicts the large temperature variability in May 2025.

The post Guest post: How the Greenland ice sheet fared in 2025 appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Guest post: Why cities need more than just air conditioning for extreme heat

Cities around the world are facing more frequent and intense bouts of extreme heat, leading to an increasing focus on the use of air conditioning to keep urban areas cool.

With the UK having experienced its hottest summer on record in 2025, for example, there was a wave of media attention on air conditioning use.

Yet less than 5% of UK homes have air conditioning and those most vulnerable – older adults, low-income households or people with pre-existing health conditions – often cannot afford to install or operate it.

While air conditioning may be appropriate in certain contexts, such as hospitals, community spaces or care homes, it is not the only solution.

Our research as part of the IMAGINE Adaptation project shows that a universal focus on technical solutions risks deepening inequality and has the potential to overlook social, economic and environmental realities.

Instead, to adapt to record temperatures, our research suggests a keener focus on community and equity is needed.

Contextualising urban heat vulnerability

In the UK, heatwaves are becoming more frequent and severe. Moreover, the evidence points to significant disparities in exposure and vulnerability. By 2080, average summer temperatures could rise by up to 6.7C, according to the Met Office.

During the summer of 2023, around 2,295 heat-related deaths occurred across the UK, with 240 in the South West region. Older adults, particularly those over 65, were the most affected, government figures show.

A recent UN Environment Programme report highlights that there is an “urgent” need for adaptation strategies to deal with rising summer heat.

However, our research shows that framing air conditioning as the default solution risks worsening urban heat by increasing emissions and energy bills, as well as missing the opportunity to design more inclusive, human-centred responses to rising temperatures.

Addressing both gradual and extreme heat involves understanding who is most affected, how people move through cities and the role of social networks.

In recognition of this, cities around the world are already developing potential cooling strategies that combine low-emission interventions with community-based care.

Expanding the concept of ‘cool spaces’

In the UK, Bristol City Council is working on a “cool space” initiative with support from the European Research Council-funded project IMAGINE Adaptation.

The initiative aims to identify a network of public spaces that can offer respite during periods of extreme heat. These spaces can potentially include parks, libraries, community centres or even urban farms.

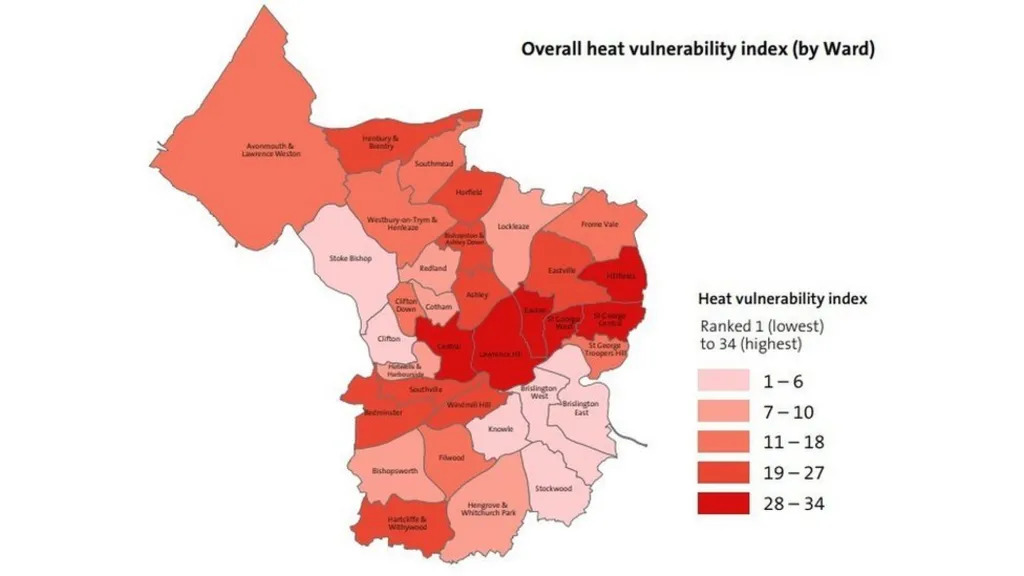

The map below shows how heat vulnerability varies across the city of Bristol, identifying neighbourhoods most at risk from current and future heatwaves.

But what makes a space “cool”? We used surveys, interviews and workshops to collectively come to an understanding of what a cool space means for Bristol communities.

What emerged from our work is that “cool” is about far more than temperature.

Shade, natural ventilation, seating, access to water and toilets all contribute to comfort, but they do not capture the full picture.

Social and cultural factors, such as whether people feel welcome, whether spaces are free to use or whether children can safely reach them, are equally important. For example, we found that while many community spaces are open to the public, people are often unsure whether they can spend time there without having to buy something.

Our research shows that the presence of a café, even unintentionally, can signal that time and space come at a cost. Clear signage, free entry, drinking water and toilets can help people feel that they are welcome to stay.

Additionally, our research highlights that it is important to recognise that public space is not experienced equally by everyone. Some city centre parks, for instance, may be seen as unwelcoming by people who do not drink alcohol or who feel uncomfortable around noise and large groups.

Creating cool spaces that serve the whole community involves understanding these dynamics and exploring more inclusive alternatives.

Connecting adaptation efforts

The importance of understanding the dynamics of adaptation efforts is especially relevant when considering children, as they are often more vulnerable to increasing temperatures.

At Felix Road adventure playground – one of the early pilot sites in Bristol – staff introduced shaded areas, drinking water and ice lollies to support children during hot weather.

However, adaptation does not just happen at individual sites, but between them, as connectivity to the playground by foot or public transport exposes children to the heat and traffic.

This highlights that adaptation to heat is a city-wide concern, as the effectiveness of individual cooling interventions can depend on both the space itself and how it can be accessed and used by vulnerable populations.

Buses and trains can become uncomfortably hot, making travel difficult for those most at risk. Our research suggests that for some, staying home might seem safer, but many lack cooling options.

Early discussions in the cool space trial show this is especially true for older adults, who also seek social contact alongside thermal comfort in community centres. Advice to stay home during heatwaves, without adequate cooling or guidance, therefore risks both physical harm and increased social isolation.

Relational approaches to adaptation

Viewing cooling as a social issue transforms how we approach urban adaptation and, more importantly, climate action.

Air conditioning reduces temperature, but it does not help foster trust or strengthen community ties. Our research shows that a well-designed community space, by contrast, integrates physical comfort with social support.

For example, they offer places where a parent can supervise children safely in water play, where an older adult might be offered a cold drink or a fan, or where people can simply rest without judgment. These small interactions, while often overlooked, can contribute to reducing heat stress, dehydration or social isolation during heatwaves, creating public spaces that are safer and more supportive for heat-vulnerable residents.

Cool spaces can also serve multiple roles. A library may host children’s activities or provide food support, while a community centre might offer advice on home cooling.

These spaces show that strong community relationships are key to real climate action, offering comfort, connection and practical help all in one place.

Our research shows that by embedding care into design, cities can build approaches to adaptation that go beyond temperature control, recognising the diverse needs of their communities.

However, to continue serving this role effectively, community spaces require ongoing support, including adequate funding, staffing and resources. Without such support, their ability to provide safe, welcoming and inclusive cooling environments for the most vulnerable can be limited.

Challenges and trade-offs

Our research finds that imagining “cool” adaptation is not without challenges.

Our reflections from the ongoing work in Bristol highlight the importance of context-sensitive, adaptive strategies that consider how people live and their needs and expectations, without neglecting the urgent demands of climate action and health protection.

What works in one neighbourhood may be unsuitable in another – and success cannot be defined solely by temperature reduction or visitor numbers.

Listening to communities, observing patterns of use and being willing to reconsider early designs through experimentation and learning are arguably essential for interventions that are socially, culturally and environmentally appropriate.

Climate change is already reshaping how cities function and how communities think and behave. Heatwaves are no longer rare events; they are increasingly intense and dangerous.

In this context, air conditioning may have a role in specific settings and for specific reasons, but it is not the sole answer. Our research shows it cannot replace locally grounded, inclusive and relational approaches to adaptation.

Bristol’s “cool spaces” initiative demonstrates that interventions are most likely to be effective when they are accessible, welcoming and build community, providing more than just shade or technical relief.

This requires investment, coordination and time, but also a shift in perspective: cooling is not just a technical challenge, but about how we look after one another and how we collectively imagine our public spaces in a changing climate.

The post Guest post: Why cities need more than just air conditioning for extreme heat appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Guest post: Why cities need more than just air conditioning for extreme heat

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 12 December: EU under ‘pressure’; ‘Unusual warmth’ explained; Rise of climate boardgames

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

EU sets 2040 goal

CUT CRUNCHED: The EU agreed on a legally binding target to reduce greenhouse gas emissions by 90% from 1990 levels by 2040, reported the EU Observer. The publication said that this agreement is “weaker” than the European Commission’s original proposal as it allows for up to five percentage points of a country’s cuts to be achieved by the use of foreign carbon credits. Even in its weakened form, the goal is “more ambitious than most other major economies’ pledges”, according to Reuters.

PETROL CAR U-TURN: Commission president Ursula von der Leyen has agreed to “roll back an imminent ban on the sale of new internal combustion-engined cars and vans after late-night negotiations with the leader of the conservative European People’s Party,” reported Euractiv. Car makers will be able to continue selling models with internal combustion engines as long as they reduce emissions on average by 90% by 2035, down from a previously mandated 100% cut. Bloomberg reported that the EU is “weighing a five-year reprieve” to “allow an extension of the use of the combustion engine until 2040 in plug-in hybrids and electric vehicles that include a fuel-powered range extender”.

CORPORATE PRESSURE: Reuters reported that EU countries and the European parliament struck a deal to “cut corporate sustainability laws, after months of pressure from companies and governments”. It noted that the changes exempt businesses with fewer than 1,000 employees from reporting their environmental and social impact under the corporate sustainability reporting directive. The Guardian wrote that the commission is also considering a rollback of environment rules that could see datacentres, artificial intelligence (AI) gigafactories and affordable housing become exempt from mandatory environmental impact assessments.

Around the world

- EXXON BACKPEDALS: The Financial Times reported on ExxonMobil’s plans to “slash low-carbon spending by a third”, amounting to a reduction of $10bn over the next 5 years.

- VERY HOT: 2025 is “virtually certain” to be the second or third-hottest year on record, according to data from the EU’s Copernicus Climate Change Service, covered by the Guardian. It reported that global temperatures from January-November were, on average, 1.48C hotter than preindustrial levels.

- WEBSITE WIPE: Grist reported that the US Environmental Protection Agency has erased references to the human causes of climate change from its website, focusing instead on “natural processes”, such as variations in the Earth’s orbit. On BlueSky, Carbon Brief contributing editor Dr Zack Labe described the removal as “absolutely awful”.

- UN REPORT: The latest global environment outlook, a largest-of-its-kind UN environment report, “calls for a new approach to jointly tackle the most pressing environmental issues including climate change and biodiversity loss”, according to the Associated Press. However, report co-chair Sir Robert Watson told BBC News that a “small number of countries…hijacked the process”, diluting its potential impact.

$80bn

The amount that Chinese firms have committed to clean technology investments overseas in the past year, according to Reuters.

Latest climate research

- Increases in heavy rainfall and flooding driven by fossil-fuelled climate change worsened recent floods in Asia | World Weather Attribution

- Human-caused climate change played a “substantial role” in driving wildfires and subsequent smoke concentrations in the western US between 1992-2020 | Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- Thousands of land vertebrate species over the coming decades will face extreme heat and “unsuitable habitats” throughout “most, or even all” of their current ranges | Global Change Biology

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

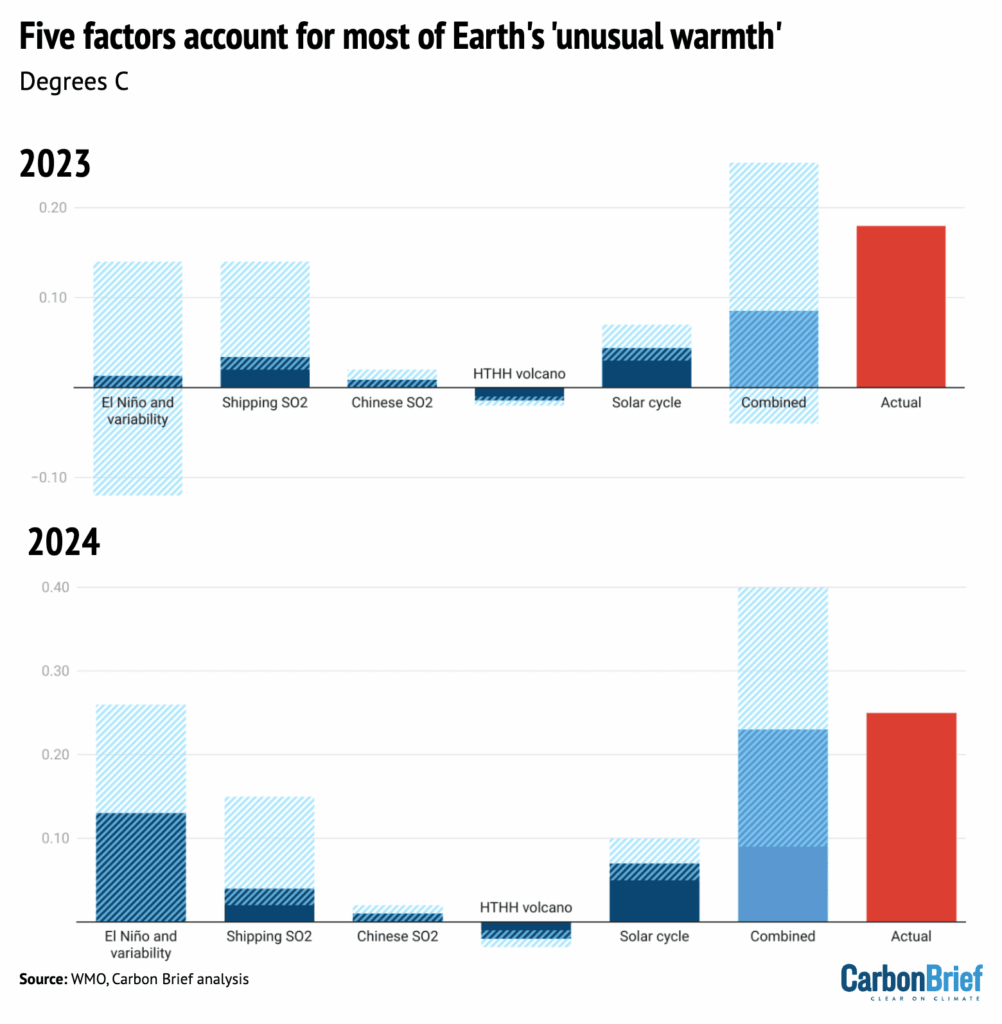

The years 2023 and 2024 were the warmest on record – and 2025 looks set to join them in the top three. The causes of this apparent acceleration in global warming have been subject to a lot of attention in both the media and the scientific community. The charts above, drawn from a new Carbon Brief analysis, show how the natural weather phenomenon El Niño, sulphur dioxide (SO2) emissions from shipping, Chinese SO2, an eruption from the Hunga Tonga-Hunga Ha’apai volcano and solar cycle changes account for most of the “unusual warmth” of recent years. Dark blue bars represent the contribution of individual factors and their uncertainties (hatched areas), the light blue bar shows the combined effects and combination of uncertainties and the red bar shows the actual warming, compared with expectations.

Spotlight

Climate change boardgames

This week, Carbon Brief reports on the rise of climate boardgames.

Boardgames have always made political arguments. Perhaps the most notorious example is the Landlord’s Game published by US game designer and writer Lizzie Magie in 1906, which was designed to persuade people of the need for a land tax.

This game was later “adapted” by US salesman Charles Darrow into the game Monopoly, which articulates a very different set of values.

In this century, game designers have turned to the challenge of climate change.

Best-selling boardgame franchise Catan has spawned a New Energies edition, where players may choose to “invest in clean energy resources or opt for cheaper fossil fuels, potentially causing disastrous effects for the island”.

But perhaps the most notable recent release is 2024’s Daybreak, which won the prestigious Kennerspiel des Jahre award (the boardgaming world’s equivalent of the Oscars).

Rolling the dice

Designed by gamemakers Matteo Menapace and Matt Leacock, Daybreak sees four players take on the role of global powers: China, the US, Europe and “the majority world”, each with their own strengths and weaknesses.

Through playing cards representing policy decisions and technologies, players attempt to reach “drawdown”, a state where they are collectively producing less CO2 than they are removing from the atmosphere.

“Games are good at modelling systems and the climate crisis is a systemic crisis,” Daybreak co-designer Menapace told Carbon Brief.

In his view, boardgames can be a powerful tool for getting people to think about climate change. He said:

“In a video game, the rules are often hidden or opaque and strictly enforced by the machine’s code. In contrast, a boardgame requires players to collectively learn, understand and constantly negotiate the rules. The players are the ‘game engine’. While videogames tend to operate on a subconscious level through immersion, boardgames maintain a conscious distance between players and the material objects they manipulate.

“Whereas videogames often involve atomised or heavily mediated social interactions, boardgames are inherently social experiences. This suggests that playing boardgames may be more conducive to the exploration of conscious, collective, systemic action in response to the climate crisis.”

Daybreak to Dawn

Menapace added that he is currently developing “Dawn”, a successor to Daybreak, building on lessons he learned from developing the first game, telling Carbon Brief:

“I want the next game to be more accessible, especially for schools. We learned that there’s a lot of interest in using Daybreak in an educational context, but it’s often difficult to bring it to a classroom because it takes quite some time to set up and to learn and to play.

“Something that can be set up quickly and that can be played in half the time, 30 to 45 minutes rather than an hour [to] an hour and a half, is what I’m currently aiming for.”

Dawn might also introduce a new twist that explores whether countries are truly willing to cooperate on solving climate change – and whether “rogue” actors are capable of derailing progress, he continued:

“Daybreak makes this big assumption that the world powers are cooperating, or at least they’re not competing, when it comes to climate action. [And] that there are no other forces that get in the way. So, with Dawn, I’m trying to explore that a bit more.

“Once the core game is working, I’d like to build on top of that some tensions, maybe not perfect cooperation, [with] some rogue players.”

Watch, read, listen

WELL WATCHERS: Mother Jones reported on TikTok creators helping to hold oil companies to account for cleaning up abandoned oil wells in Texas.

RUNNING SHORT: Wired chronicled the failure of carbon removal startup Running Tide, which was backed by Microsoft and other tech giants.

PARIS IS 10: To mark the 10th anniversary of the Paris Agreement, climate scientist Prof Piers Forster explained in Climate Home News “why it worked” and “what it needs to do to survive”.

Coming up

- 15-19 December: American Geophysical Union (AGU) annual meeting, New Orleans

- 15-19 December: 70th Meeting of the Global Environment Facility (Gef) Council, online

- 16 December: International Energy Agency: Future of electricity in the Middle East and North Africa webinar, online

Pick of the jobs

- Natural Resources Wales, senior strategic environmental policy specialist | Salary: Unknown. Location: Wales (hybrid)

- The Nature Conservancy, director of conservation – Mata Atlântica | Salary: Unknown. Location: São Paulo, Belo Horizonte, Rio de Janeiro and nearby cities, Brazil

- Barcelona Supercomputing Centre, postdoctoral researcher – downscaling for climate services | Salary: Unknown. Location: Barcelona, Spain

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 12 December: EU under ‘pressure’; ‘Unusual warmth’ explained; Rise of climate boardgames appeared first on Carbon Brief.

DeBriefed 12 December: EU under ‘pressure’; ‘Unusual warmth’ explained; Rise of climate boardgames

-

Climate Change4 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases4 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Why airlines are perfect targets for anti-greenwashing legal action