Next week’s seventh meeting of the board of the Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD) in Manila presents a critical moment for a course correction.

The fund’s establishment in 2022 was hailed by climate justice advocates. However, three years later, its operations and future are hampered by insufficient attention to human rights and the communities most impacted, as well as a severe lack of resources. Currently, less than 0,1% of the estimated funding needs are in the FRLD’s bank account.

Key items on the Manila meeting’s agenda, including the fund’s start-up phase and its long-awaited resource mobilization strategy, could change this. It’s also the first meeting since the International Court of Justice (ICJ)’s historic advisory opinion on the legal obligations of states in respect of climate change.

This authoritative legal opinion clarifies states’ loss and damage obligations and has significant implications for ensuring that the fund will effectively deliver resources at scale directly to communities on the frontlines of the climate crisis, in line with their right to remedy.

A long-awaited clarification

The advisory opinion comes with unparalleled legitimacy: all countries agreed through a consensus resolution by the UN General Assembly to ask the ICJ for guidance on their international legal obligations in the context of climate change.

Decades of foot-dragging and deliberate blockage under the climate regime have led to rapidly escalating climate harm. It’s therefore no surprise that the most climate-vulnerable countries, like small island developing states and their communities, led the charge on taking climate change up to the world’s highest court.

The importance of this ruling – an authoritative interpretation of binding international law – cannot be understated, particularly for loss and damage.

Legal obligation to remedy climate harm

The court strongly affirmed that climate harm – also known as loss and damage – is a reality that requires dedicated responses and finance as a matter of obligations, including within the climate regime. This is especially true for those most responsible for causing the crisis, in line with long-established principles of equity and Common But Differentiated Responsibilities.

The ICJ also affirmed loud and clear that human rights law is critical to interpreting and addressing loss and damage: not only is the climate crisis harming a wide range of fundamental human rights, but rights-based principles and standards are also fundamental to loss and damage responses.

Additionally, by looking at international law holistically, the court endorsed what grassroots movements have long known: frontline communities and countries have a right to full reparation.

The court confirmed the basic principle of international law that those who breach their legal obligations, including under the climate treaties, have a duty to repair the harm they cause. In explicitly recognizing legal consequences for “peoples and individuals”, the ICJ reaffirmed communities as direct rights-holders for such reparations.

How the fund should respond to ICJ decision

As board members consider the fund’s future, they must ensure that loss and damage responses are fully consistent with international law. This will be essential to overcoming longstanding impasses and to building an institution that is founded on justice.

First and foremost, states have a duty to provide resources at the scale of loss and damage needs, based on their Common But Differentiated Responsibilities. This has important implications for the upcoming resource mobilization strategy for the FRLD, both in terms of the scale that it needs to aim for – as needs are in the hundreds of billions – and how to reach it.

Rich nations accused of delaying loss and damage fund with slow payments

The board must move beyond voluntary contributions and periodic pledging conferences to clarifying differentiated obligations, with concrete pathways to make polluters pay and hold big polluters accountable.

Second, all those harmed by the climate crisis have a right to remedy – not charitable assistance. This has critical implications for decisions on access to the fund.

Bureaucratic rules and the limitations imposed by the World Bank as the FRLD’s trustee cannot stand in the way of all climate-vulnerable developing countries having direct access to the fund. Moreover, as the ICJ affirmed, the legal consequences of states’ wrongful acts extend to peoples and individuals, making direct community access a matter of right rather than discretion.

NGOs urge Brazil to prevent fossil fuel capture of COP30 climate summit

Third, international human rights law must guide loss and damage responses as a legal requirement, not as best practice. The fund’s start-up phase and long-term operations should recognize that losses and damages are, first and foremost, human rights violations and adjust accordingly.

Loss and damage needs assessments must explicitly include human rights criteria and non-economic loss and damage. The fund must urgently develop policies and do-no-harm frameworks that ensure inclusive, participatory, and accountable operations that protect ecosystems and human rights, including Indigenous Peoples’ rights.

‘There is no going back’

The momentum for climate justice needs to continue after the fund’s board meeting. At COP30 in Belém, Brazil, states are expected to finally deliver action consistent with their legal obligations on mitigation, adaptation and loss and damage.

Beyond COP30, the Pacific island nation of Vanuatu has announced its push for a new UN General Assembly resolution to endorse and operationalize the ICJ’s advisory opinion.

All states have agreed that guidance from the ICJ on legal climate obligations was necessary. Now, they must deliver urgent, tangible solutions for the communities most affected by the climate crisis. The legal landscape has shifted – there is no going back to a world where climate accountability can be evaded.

Liane Schalatek is associate director of the Heinrich-Böll-Stiftung in Washington DC. Lien Vandamme is a senior campaigner at the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL). Monica Iyer is an assistant professor at the Georgia State University College of Law. Rajib Ghosal is an international consultant working on climate justice and development. Teo Ormond-Skeaping is a coordinator of advocacy and outreach at the Loss and Damage Collaboration. Isatis M. Cintron is a climate justice postdoctoral researcher and director of the ACE Observatory.

The post The ICJ climate ruling has major implications for the loss and damage fund appeared first on Climate Home News.

The ICJ climate ruling has major implications for the loss and damage fund

Climate Change

Analysis: UK newspaper editorial opposition to climate action overtakes support for first time

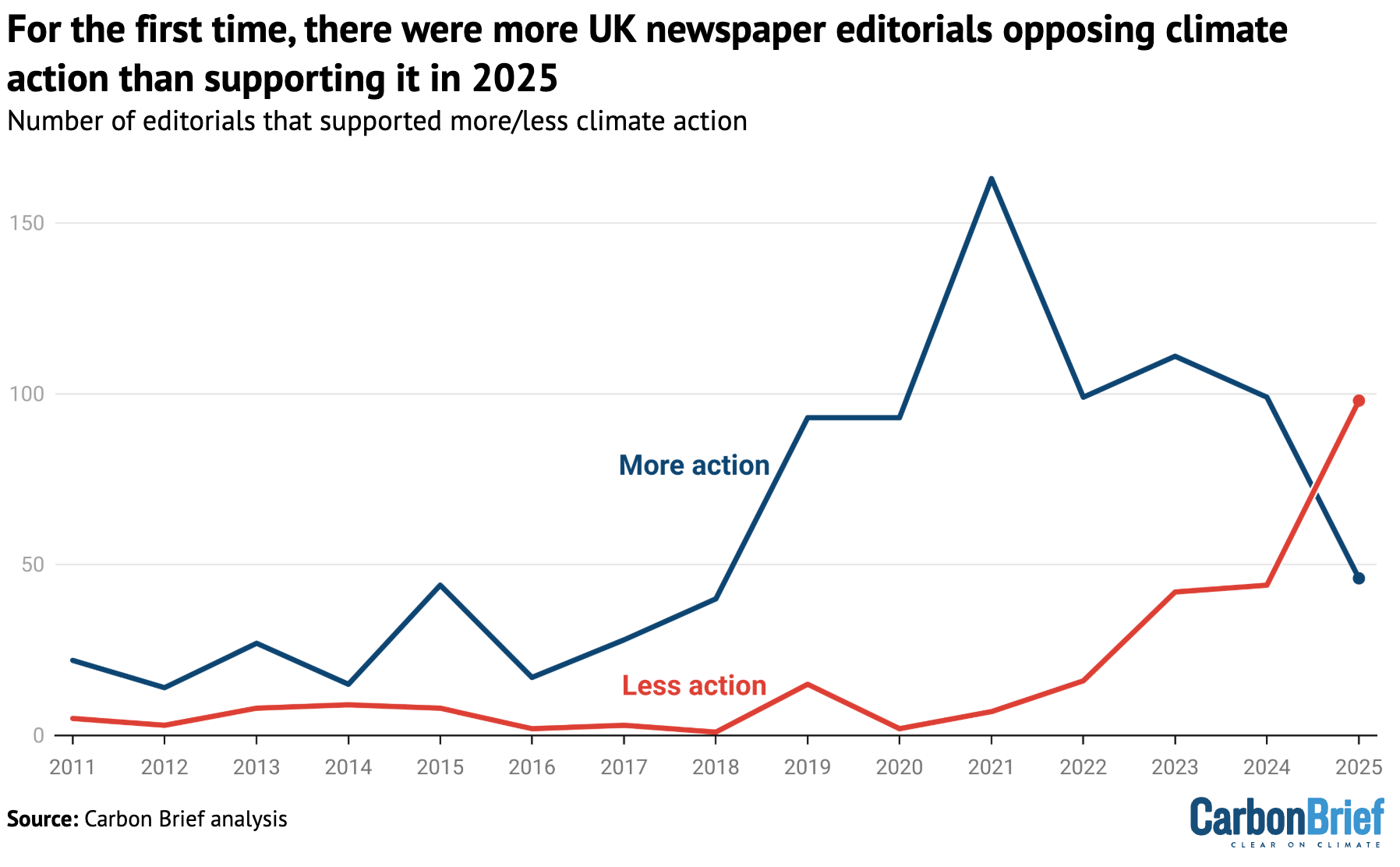

Nearly 100 UK newspaper editorials opposed climate action in 2025, a record figure that reveals the scale of the backlash against net-zero in the right-leaning press.

Carbon Brief has analysed editorials – articles considered the newspaper’s formal “voice” – since 2011 and this is the first year opposition to climate action has exceeded support.

Criticism of net-zero policies, including renewable-energy expansion, came entirely from right-leaning newspapers, particularly the Sun, the Daily Mail and the Daily Telegraph.

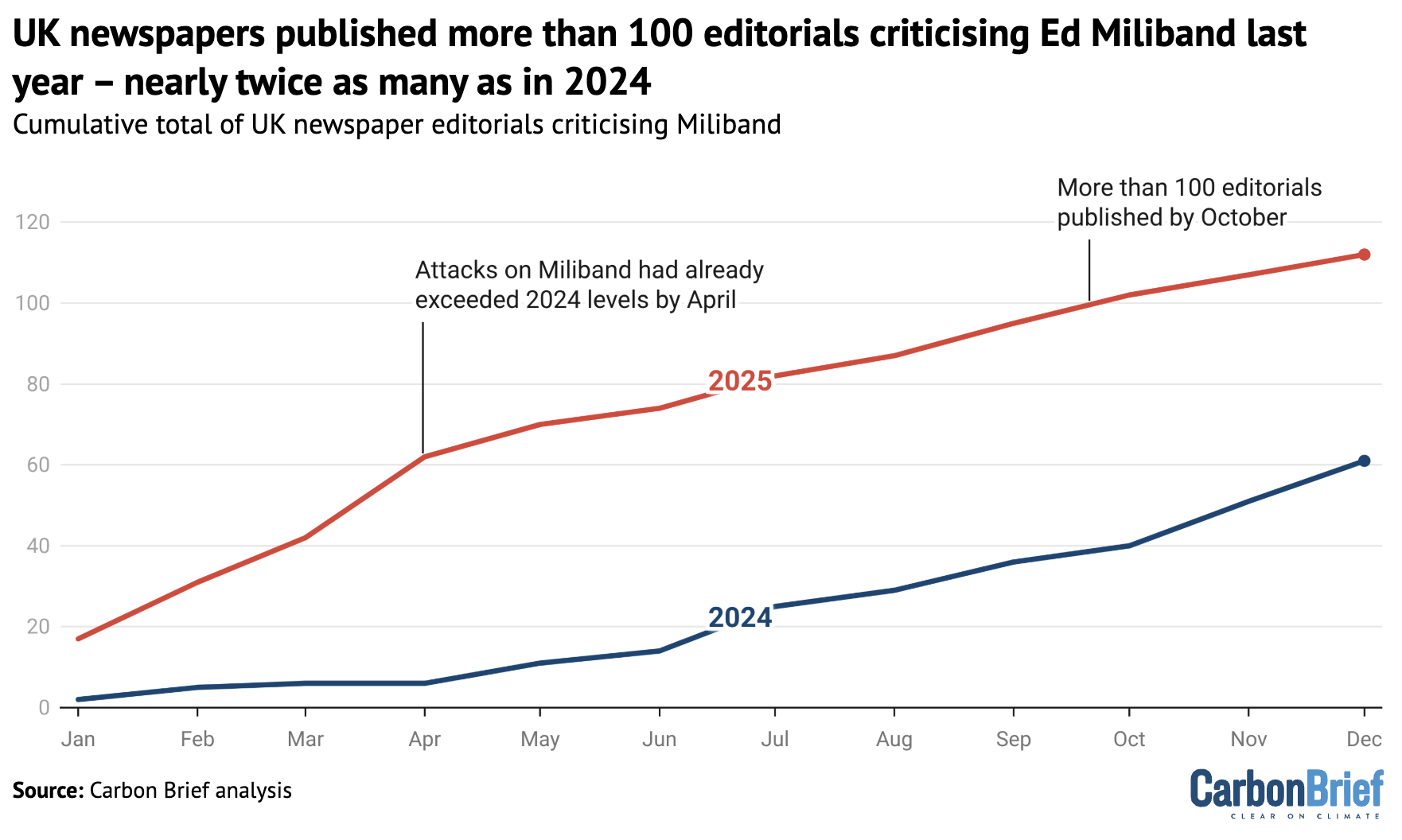

In addition, there were 112 editorials – more than two a week – that included attacks on Ed Miliband, continuing a highly personal campaign by some newspapers against the Labour energy secretary.

These editorials, nearly all of which were in right-leaning titles, typically characterised him as a “zealot”, driving through a “costly” net-zero “agenda”.

Taken together, the newspaper editorials mirror a significant shift on the UK political right in 2025, as the opposition Conservative party mimicked the hard-right populist Reform UK party by definitively rejecting the net-zero target that it had legislated for and the policies that it had previously championed.

Record climate opposition

Nearly 100 UK newspaper editorials voiced opposition to climate action in 2025 – more than double the number of editorials that backed climate action.

As the chart below shows, 2025 marked the fourth record-breaking year in a row for criticism of climate action in newspaper editorials.

This also marks the first time that editorials opposing climate action have overtaken those supporting it, during the 15 years that Carbon Brief has analysed.

This trend demonstrates the rapid shift away from a long-standing political consensus on climate change by those on the UK’s political right.

Over the past year, the Conservative party has rejected both the “net-zero by 2050” target that it legislated for in 2019 and the underpinning Climate Change Act that it had a major role in creating. Meanwhile, the Reform UK party has been rising in the polls, while pledging to “ditch net-zero”.

These views are reinforced and reflected in the pages of the UK’s right-leaning newspapers, which tend to support these parties and influence their politics.

All of the 98 editorials opposing climate action were in right-leaning titles, including the Sun, the Daily Mail, the Daily Telegraph, the Times and the Daily Express.

Conversely, nearly all of the 46 editorials pushing for more climate action were in the left-leaning and centrist publications the Guardian and the Financial Times. These newspapers have far lower circulations than some of the right-leaning titles.

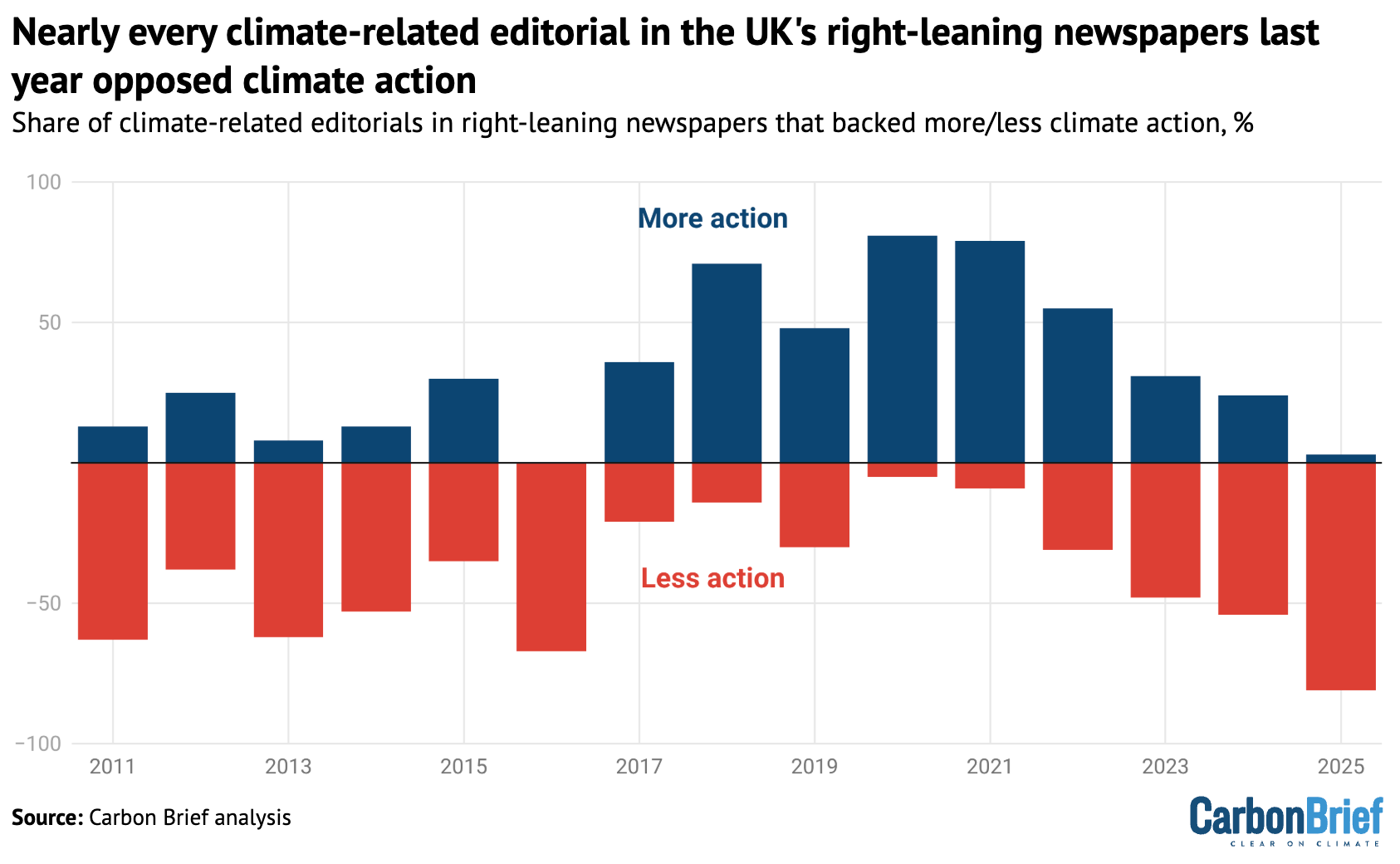

In total, 81% of the climate-related editorials published by right-leaning newspapers in 2025 rejected climate action. As the chart below shows, this is a marked difference from just a few years ago, when the same newspapers showed a surge in enthusiasm for climate action.

That trend had coincided with Conservative governments led by Theresa May and Boris Johnson, which introduced the net-zero goal and were broadly supportive of climate policies.

Notably, none of the editorials opposing climate action in 2025 took a climate-sceptic position by questioning the existence of climate change or the science behind it. Instead, they voiced “response scepticism”, meaning they criticised policies that seek to address climate change.

(The current Conservative leader, Kemi Badenoch, has described herself as “a net-zero sceptic, not a climate change sceptic”. This is illogical as reaching net-zero is, according to scientists, the only way to stop climate change from getting worse.)

In particular, newspapers took aim at “net-zero” as a catch-all term for policies that they deemed harmful. Most editorials that rejected climate action did not even mention the word “climate”, often using “net-zero” instead.

This supports recent analysis by Dr James Painter, a research associate at the University of Oxford, which concluded that UK newspaper coverage has been “decoupling net-zero from climate change”.

This is significant, given strong and broad UK public support for many of the individual climate policies that underpin net-zero. Notably, there is also majority support for the “net-zero by 2050” target itself.

Much of the negative framing by politicians and media outlets paints “net-zero” as something that is too expensive for people in the UK.

In total, 87% of the editorials that opposed climate action cited economic factors as a reason, making this by far the most common justification. Net-zero goals were described as “ruinous” and “costly”, as well as being blamed – falsely – for “driving up energy costs”.

The Sunday Telegraph summarised the view of many politicians and commentators on the right by stating simply that said “net-zero should be scrapped”.

While some criticism of net-zero policies is made in good faith, the notion that climate change can be stopped without reducing emissions to net-zero is incorrect. Alternative policies for tackling climate change are rarely presented by critical editorials.

Moreover, numerous assessments have concluded that the transition to net-zero can be both “affordable” and far cheaper than previously thought.

This transition can also provide significant economic benefits, even before considering the evidence that the cost of unmitigated warming will significantly outweigh the cost of action.

Miliband attacks intensify

Meanwhile, UK newspapers published 112 editorials over the course of 2025 taking personal aim at energy security and net-zero secretary Ed Miliband.

Nearly all of these articles were in right-leaning newspapers, with the Sun alone publishing 51. The Daily Mail, the Daily Telegraph and the Times published most of the remainder.

This trend of relentlessly criticising Miliband personally began last year in the run up to Labour’s election victory. However, it ramped up significantly in 2025, as the chart below shows.

Around 58% of the editorials that opposed climate action used criticism of climate advocates as a justification – and nearly all of these articles mentioned Miliband, specifically.

Editorials denounced Miliband as a “loon” and a “zealot”, suffering from “eco insanity” and “quasi-religious delusions”. Nicknames given to him include “His Greenness”, the “high priest of net-zero” and “air miles Miliband”.

Many of these attacks were highly personal. The Daily Mail, for example, called Miliband “pompous and patronising”, with an “air of moral and intellectual superiority”.

Frequently, newspapers refer to “Ed Miliband’s net-zero agenda”, “Ed Miliband’s swivel-eyed targets” and “Mr Miliband’s green taxes”.

These formulations frame climate policies as harmful measures that are being imposed on people by the energy secretary.

In fact, the Labour government decisively won an election in 2024 with a manifesto that prioritised net-zero policies. Often, the “targets” and “taxes” in question are long-standing policies that were introduced by the previous Conservative government, with cross-party support.

Moreover, the government’s climate policy not only continues to rely on many of the same tools created by previous administrations, it is also very much in line with expert evidence and advice. This is to prioritise the expansion of clean power and to fuel an economy that relies on increasing levels of electrification, including through electric cars and heat pumps.

Despite newspaper editorials regularly calling for Miliband to be “sacked”, prime minister Keir Starmer has voiced his support both for the energy secretary and the government’s prioritisation of net-zero.

In an interview with podcast The Rest is Politics last year, Miliband was asked about the previous Carbon Brief analysis that showed the criticism aimed at him by right-leaning newspapers.

Podcast host Alastair Campbell asked if Miliband thought the attacks were the legacy of his strong stance, while Labour leader, during the Leveson inquiry into the practices of the UK press. Miliband replied:

“Some of these institutions don’t like net-zero and some of them don’t like me – and maybe quite a lot of them don’t like either.”

Renewable backlash

As well as editorial attitudes to climate action in general, Carbon Brief analysed newspapers’ views on three energy technologies – renewables, nuclear power and fracking.

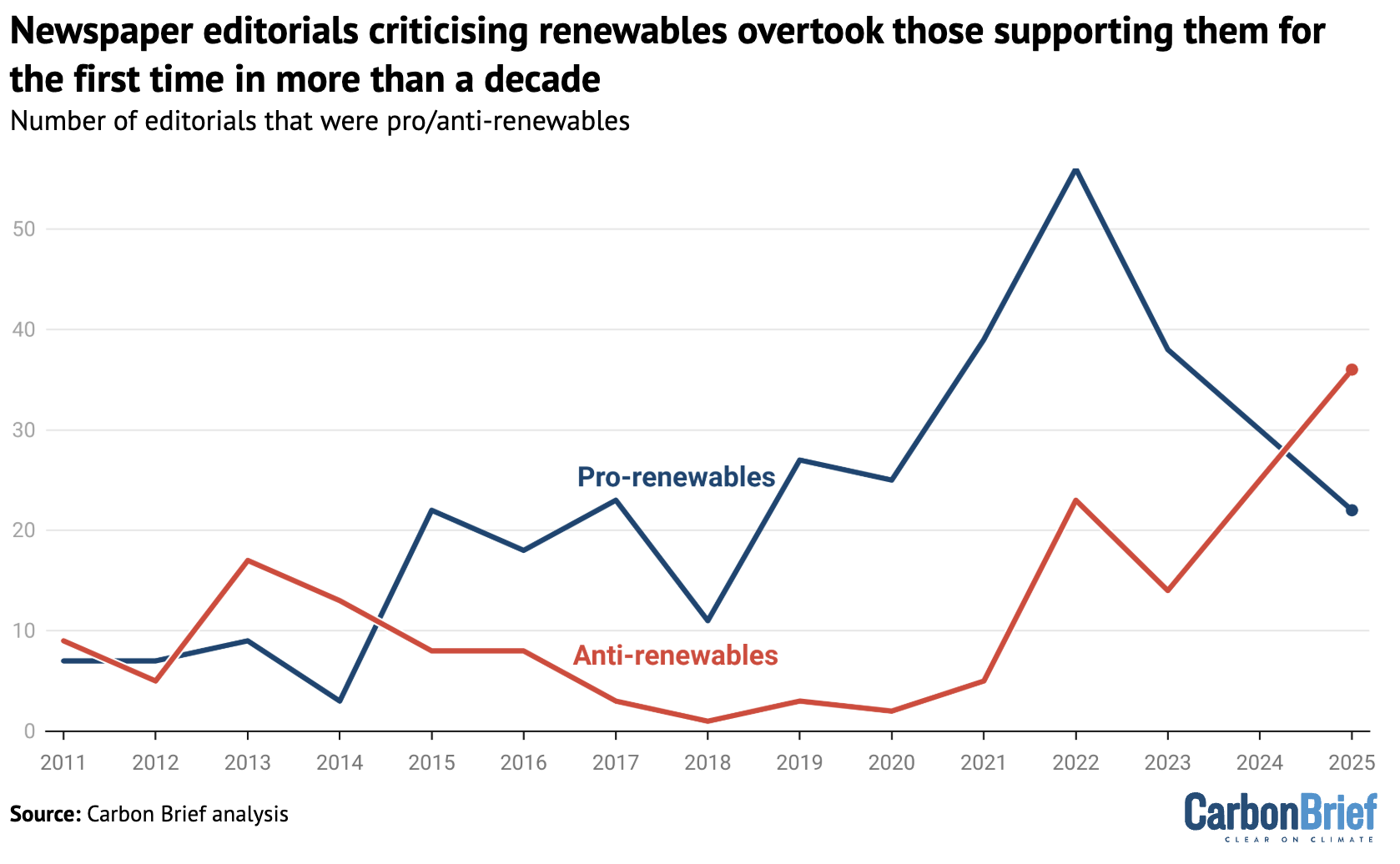

There were 42 newspaper editorials criticising renewable energy in 2025. This meant that, for the first time since 2014, there were more anti-renewables editorials than pro-renewables editorials, as the chart below shows.

As with climate action more broadly, this was a highly partisan issue. The Times was the only right-leaning newspaper that published any editorials supporting renewables.

By far the most common stated reason for opposing renewable energy was that it is “expensive”, with 86% of critical editorials using economic arguments as a justification.

The Sun referred to “chucking billions at unreliable renewables” while the Daily Telegraph warned of an “expensive and intermittent renewables grid”.

At the same time, editorials in supportive publications also used economic arguments in favour of renewables. The Guardian, for example, stressed the importance of building an “affordable clean-energy system” that is “built on renewables”.

There was continued support in right-leaning publications for nuclear power, despite the high costs associated with the technology. In total, there were 20 editorials supporting nuclear power in 2025 – nearly all in right-leaning newspapers – and none that opposed it.

Fracking was barely mentioned by newspapers in 2023 and 2024, after a failed push by the Conservatives under prime minister Liz Truss to overturn a ban on the practice in 2022. This attempt had been accompanied by a surge in supportive right-leaning newspaper editorials.

There was a small uptick of 15 editorials supporting fracking in 2025, as right-leaning newspapers once again argued that it would be economically beneficial.

The Sun urged current Conservative leader Badenoch to make room for this “cheap, safe solution” in her future energy policy. The government plans to ban fracking “permanently”.

North Sea oil and gas remained the main fossil-fuel policy focus, with 30 editorials – all in right-leaning newspapers – that mentioned the topic. Most of the editorials arguing for more extraction from the North Sea also argued for less climate action or opposed renewable energy.

None of these editorials noted that the UK is expected to be significantly less reliant on fossil-fuel imports if it pursues net-zero, than if it rolls back on climate action and attempts to squeeze more out of the remaining deposits in the North Sea.

Methodology

This is a 2025 update of previous analysis conducted for the period 2011-2021 by Carbon Brief in association with Dr Sylvia Hayes, a research fellow at the University of Exeter. Previous updates were published in 2022, 2023 and 2024.

The count of editorials criticising Ed Miliband was not conducted in the original analysis.

The full methodology can be found in the original article, including the coding schema used to assess the language and themes used in editorials concerning climate change and energy technologies.

The analysis is based on Carbon Brief’s editorial database, which is regularly updated with leading articles from the UK’s major newspapers.

The post Analysis: UK newspaper editorial opposition to climate action overtakes support for first time appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: UK newspaper editorial opposition to climate action overtakes support for first time

Climate Change

Power play: Can a defensive Europe stick with decarbonisation in Davos?

Tsvetelina Kuzmanova is EU sustainable finance lead for the University of Cambridge Institute for Sustainability Leadership (CISL), based in Brussels.

Europe is set to arrive in Davos on the defensive after a year of trade uncertainty and tariff threats from the Trump administration, as well as pressure to roll back core elements of the EU’s Green Deal. The war in Ukraine and situation in Greenland also continue to test Europe’s security and strategic cohesion.

While Trump’s administration is “coming in force” to the World Economic Forum in the Swiss ski resort of Davos with the largest-ever US delegation, Europe is not showing up in a strong position or as a shaper of the global agenda. Instead, it has become reactive to other global powers.

Amid the pressure, it is crucial that the EU maintains its ambitions on energy security and decarbonisation, both against headwinds at Davos and by continuing to uphold the energy transition. This is not about climate leadership alone, but a question of power and independence. Maintaining the energy transition is central to reducing geopolitical exposure, limiting external leverage and preserving Europe’s ability to act strategically, including in negotiations on the next EU budget.

Over the past year, debates in Europe have increasingly framed climate ambition as a liability to competitiveness. Green policies have been softened, delayed or revised in the name of industrial survival.

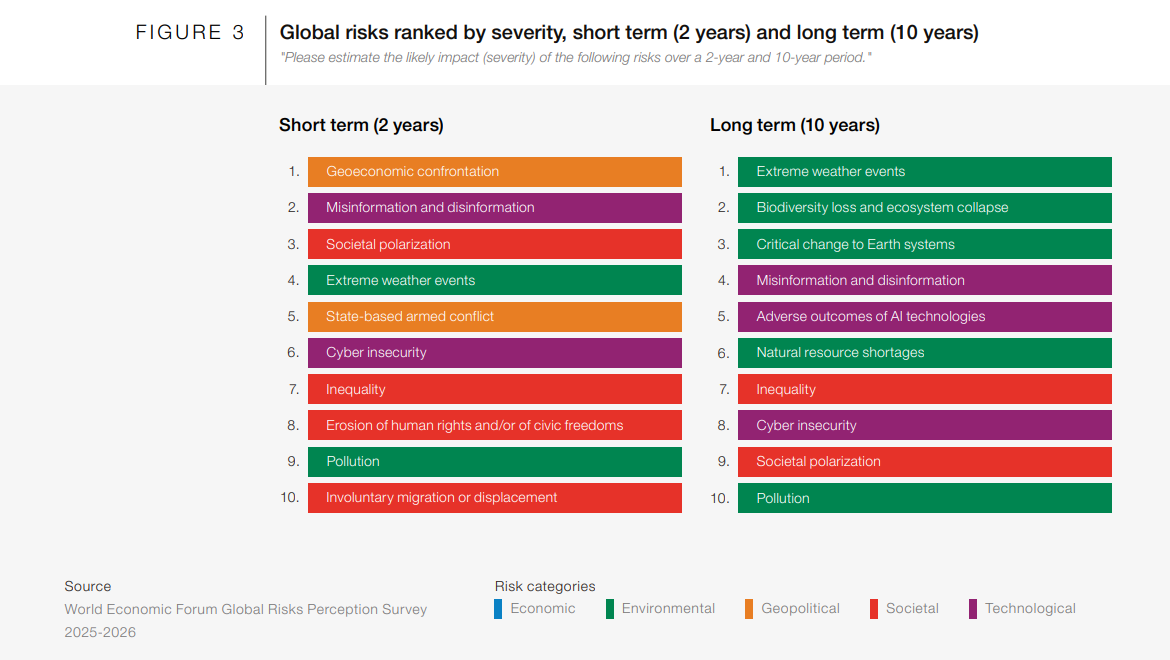

Yet global leaders identify climate-driven disruption as the most likely defining risk of the 2030s. Looking a decade into the future, climate collapse and extreme weather dominate the risk landscape, according to the World Economic Forum’s newly published Global Risks Report 2026 . Economic downturn, by contrast, sits far lower on the list at 24.

Near-term risks for Europe

Even setting aside the risk of climate change, Europe’s vulnerabilities are painfully concrete in the short-term: energy remains a pressure point, trade is increasingly weaponised, supply chains are exposed, and geopolitical leverage continues to be exercised through fossil fuel supplies.

If recent history taught Europe anything, it should have been that such dependency directly threatens economic prosperity, as was seen during the 2022 energy crisis.

Oil and gas remain central to geopolitical arm-twisting, including supply threats, price manipulation or diplomatic pressure – for example, the US and Qatar telling the European Union that its corporate sustainability due diligence directive threatens LNG supplies to the bloc.

Strategic spending or strategic drift

In this context, the EU budget is a geopolitical choice as much as a fiscal exercise. It will run until 2034, meaning it overlaps almost exactly with when long-term risks will become tomorrow’s reality and frame Europe’s place on the global stage for almost a decade.

Choices will have to be made as public money is scarce and there is no chance of further joint European debt. The question is whether Europe uses its limited fiscal firepower to preserve the status quo or to address its vulnerabilities and the long-term economic risks.

This is where electrification, grids, incentivising cleantech and greening Europe’s heavy industry come in. These shouldn’t be viewed just as climate projects, but as instruments of strategic autonomy.

Governments defend clean energy transition as US snubs renewables agency

Other economies are already doing this. China will spend 4 trillion yuan ($574 billion) by 2030 in electricity grid infrastructure, treating transmission and system balancing as core national assets.

Even under the Trump administration, the US has continued to scale up grid investment. Last year, it recorded the highest level of grid spending globally, at around $115 billion, accounting for roughly a quarter of total worldwide investment. A significant share of this has been driven by federal funding for grid modernisation and transmission expansion, explicitly linking energy infrastructure to industrial competitiveness and security.

Meanwhile, Europe estimates that it needs close to €600 billion in grid investment by 2030, yet annual spending remains fragmented across national systems and constrained by permitting and financing bottlenecks. This comparison underscores why the next Multiannual Financial Framework (the EU budget) must prioritise strategic public spending on grids, electrification and related infrastructure.

Bolstering competitiveness with electricity

Despite the narrative being pushed by the US in forums like Davos, industrial electrification, system flexibility and cleantech scale-up are prerequisites for a competitive industry in a decarbonising world.

Electrification is critical to reducing vulnerability to fossil fuel imports and grids are essential to do this at scale. This shift would also reduce Europe’s exposure to the very risks flagged by the World Economic Forum, from climate-driven instability to energy and supply-chain shocks, turning vulnerability into strategic resilience.

This is a textbook case for mission-oriented public investment – not picking individual corporate winners but backing system-level capabilities that markets will not support enough despite their strategic importance.

Q&A: “False” climate solutions help keep fossil fuel firms in business

In today’s global economy, power flows from control over infrastructure, energy systems and industrial capacity. Without the underlying investment, even the most sophisticated regulatory frameworks risk becoming aspirational.

And, if Europe does not decisively shift towards investing in electrification, grids and industrial transformation, it will remain exposed to pressure tactics, with oil and gas supplies shaping Europe’s future and making it reactive rather than proactive at meetings like Davos.

Any talk of resilience, competitiveness and strategic autonomy at Davos will be hollow if Europe is unable to match it with spending decisions that address future risks and drive ahead with decarbonisation.

The post Power play: Can a defensive Europe stick with decarbonisation in Davos? appeared first on Climate Home News.

Power play: Can a defensive Europe stick with decarbonisation in Davos?

Climate Change

An Alabama Mayor Signed an NDA With a Data Center Developer. Read It Here.

The non-disclosure agreement was a major sticking point in a lively town hall that featured city officials, data center representatives and more than a hundred frustrated residents.

COLUMBIANA, Ala.—At first, no one knew about the non-disclosure agreement.

An Alabama Mayor Signed an NDA With a Data Center Developer. Read It Here.

-

Greenhouse Gases5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits