This week, the international court of justice (ICJ) opened two weeks of hearings on states’ climate-related legal obligations – and the consequences, if “significant harm” is caused.

The case stems from a unanimous UN general assembly (UNGA) request for an “advisory opinion” from the ICJ.

It is taking place against a backdrop of rapidly escalating climate impacts. Emissions continue to rise, rather than falling rapidly, as needed to avoid dangerous levels of global warming.

It is the ICJ’s largest ever case, with more than 100 countries and international organisations making interventions, deploying a wide variety of legal arguments.

Ralph Regenvanu, climate envoy for Vanuatu, which led the campaign for the ICJ hearings, said in his opening address: “[T]his may well be the most consequential case in the history of humanity.”

Below, Carbon Brief interviews leading international law scholar Prof Philippe Sands – who drafted the pleadings for Mauritius, but is speaking here in a personal capacity – to find out more about the legal issues at stake and the wider significance of the ICJ case.

- On the significance of the case: “It’s the first time the ICJ has been called upon to address legal issues relating to climate change.”

- On the key legal arguments: “There’s just a huge number of issues that are coming up.”

- On climate obligations under the UN: “Will the court open the door to the situation that the 1992 [UN climate] convention … [is] not the be all and end all?”

- On where outcomes could come from: “Essentially, it’s the whole of international law!”

- On the responsibility of states: “The question at the beating heart of this case, really, is the consequences of emissions over time.”

- On historical emissions: “The big issue is, are you liable for the continuing consequences of your past emissions?”

- On applying international law: “When drafting the climate treaty regime, [did] states…exclude the application of general international law?”

- On expectations for the case: “What I’m interested in, really, is an advisory opinion that is capable of having hard, practical application.”

- On the state of the science: “A procedure in which the judges hear privately from any person…is unusual. It’s unorthodox.”

- On the significance of the submissions: “The oral phase is very important, because it basically concentrates the issues down to the most significant and narrow set of issues.”

- On the question of the UN or wider law: “It’s a tough situation for the judges.”

Carbon Brief: Would you be able to start by just situating this case in its wider legal context and explaining why it could be so consequential?

Philippe Sands: Well, it’s the first time the international court of justice has been called upon to address legal issues relating to climate change. The ICJ is the principal judicial organ of the United Nations and, although the advisory opinion that it hands down will not be binding on states, it is binding on all UN bodies. The determinations that the court makes will have consequences that go very far and that will have a particular authority, in legal and political terms. Of course, everything turns on what the court actually says.

CB: Would you be able to summarise the key legal arguments that are being fought over in this case?

PS: No! I mean, there’s just a huge number of issues that are coming up. But, essentially, the court has been asked two questions by the UN General Assembly – the first time, I believe, that a request from the General Assembly has been consensual, with no objections. The two questions are, firstly, what are the obligations for states under international law to protect the climate system? And, secondly, what are the legal consequences under these obligations, where, by their acts and emissions, [states] cause significant harm to the climate system? So, there are two distinct questions – and about 100 states and international organisations of various kinds have made submissions on the vast range of issues that are raised by these two questions. The questions are very, very broad and that signals to me that the court’s response may be quite general. But, for me, the crucial issues are, firstly, what the court says about the state of the science: is it established, or is there any room for doubt? Secondly, what are the obligations of states having regard to the clarity of the science? Thirdly, are there legal obligations on states in relation to the climate system that exist and arise outside of the treaty regime – the 1992 [UN Framework] convention [on climate change], the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement and so on and so forth. And, related to that, fourthly – this is the most intense, legally interesting aspect – what are the responsibilities of states for historic emissions under general international law? And, in particular, are the biggest contributors liable under international law to make good any damages that may arise from their historic actions? But, I mean, there’s just such a vast array of questions that are addressed, it’s impossible to summarise briefly.

CB: This is the challenge I found when I was trying to write questions!

PS: To be honest, the questions [put by the UN General Assembly] are rather general, so I have concerns about the burden that has been imposed on the court. My general approach has been that, with advisory opinions, the best questions are those which require a yes or no answer. But the moment you have questions of such generality, you impose on the 15 judges an especially onerous burden, because the questions are open to interpretation.

CB: Some countries are arguing, effectively, that states’ climate obligations start and finish with the UN climate regime, as you’ve already mentioned.

PS: Exactly. Well, that’s a central aspect of what’s coming up. Will the court open the door to the situation that the 1992 [UN climate] convention and the subsequent agreements [Kyoto, Paris] are not the be all and end all, and that the rules of general international law [also] apply? And, if so, what are those rules? And what are the consequences of breaching those rules? Some states say there can’t be any liability under general international law because the whole matter is governed by the treaty regime. Other states say that’s not right, that, although the treaty regime is a distinct “lex specialis” – a specialised area of law – that does not preclude the application of the general principles of international law. So that may be a really interesting issue for the court to determine.

CB: Could you say a bit more about the other areas of international law, where obligations could come from, whether it’s human rights, or customary law, or whatever it might be?

PS: The difficulty, if you look at the first part of the question [put to the court]…the drafters of the question invite the court to have regard to the Charter of the United Nations, the Covenant on Civil and Political Rights, the Covenant on Economic and Social Rights, the Framework Convention on Climate Change, the Paris Agreement, the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea, the duty of due diligence, human rights law, the principle of prevention, and the duty to protect and preserve the marine environment. That is a vast array of international legal obligations and it’s not exhaustive. It says, having particular regard to, so, essentially, it’s the whole of international law! So the court is being asked to address the application of the whole of international law to the issue of climate change and, in particular, issues of legal consequences, and in particular, the issues of state responsibility. So, it’s vast, vast.

CB: Another set of arguments that I’ve seen…is around the idea of the “responsibility of states for internationally wrongful acts”, which might lead to a requirement for cessation of the acts and reparation of the harm done. Can you just say a bit more about what that idea means and where it comes from?

PS: There’s an area of international law called the law of state responsibility. That law of state responsibility says that when you have committed a wrongful act and violated a rule of international law, you are liable for all of the consequences. That rule has not been incorporated, as such, or at all, into the treaty regime [on climate change]. So, essentially, by raising those issues, there are a number of legal issues that arise – but there are two of particular interest. Firstly, in relation to damage that is caused by climate change, are those states most responsible, liable for the consequences of that damage in, let us say, for example, in financial terms? And, secondly – and this relates to something called the principle of “common but differentiated responsibility” – does the fact that certain states have historic emissions going back 200 years mean that their entitlement to the remaining “carbon budget” is reduced. So, the question, I think, at the beating heart of this case, really, is the consequences of emissions over time, looking back and looking forward. That’s one aspect the court may have at the forefront of its mind.

CB: Historical greenhouse gas emissions, but also the rights of future generations, have both come up quite a lot in some of the submissions. Can you just say a bit more about the legal arguments around these?

PS: The big issue is: are you liable for the continuing consequences of your past emissions? And does the nature and extent of your past emissions affect your ability to generate emissions in the future? Those are really the two issues and the treaty regime does not, as such, explicitly address [them]. The practicalities are that islands are disappearing with sea level rise. Are historic polluters of greenhouse gases responsible for the consequences of those disappearances? Or, if states are required to build sea walls to protect themselves, can they bring a case against the biggest polluters for the consequences of sea level rise? That’s the kind of complex issue the court may have in the back of its mind, because that’s essentially what’s being asked.

CB: In terms of how they will decide whether these other potential areas of law could give rise to obligations on states – and, therefore, potentially further consequences – how are they going to decide? To decide whether those [areas of law] do apply, or whether it is only the UN climate regime that gives rise to obligations.

PS: They are going to have to address whether, when drafting the climate treaty regime, states intended to, or did as a necessary consequence, exclude the application of general international law. That is an issue that they will do by looking at the climate regime and determining whether, by adopting it, there was an intention to exclude the application of general international law. So, that is a classical job for lawyers, for judges: to interpret the law, to interpret what the drafters of the treaty regime have done and what they intended, and to then form a view in applying the general rules of international law, whether a space is left which allows those general rules to apply. That’s classically what international judges will do.

CB: You’ve already said a little bit about this, but what would your expectations be for this advisory opinion, which I gather is expected next year?

PS: Normally, it takes six months from after they’ve done the hearings for an advisory opinion to come up. I don’t really have any expectations. There’s been a previous advisory opinion in relation to the Law of the Sea proceedings. The Tribunal for the Law of the Sea came up with an advisory opinion which, in a sense, was rather general. What I’m interested in, really, is an advisory opinion that is capable of having hard, practical application, as happened, for example, in the advisory opinion on the Chagos Archipelago, where the court was asked two questions, essentially, “yes/no” questions, and the court gave a very clear advisory opinion, which has had significant political and legal consequences. The difficulty with asking very general questions is you get very general answers, and very general answers are less easily capable of practical application. So, the best-case scenario for me, is that the court comes up with an advisory opinion of sufficient clarity on the facts, which is basically the state of the science and on the applicable legal principles, which then allows other courts and, in particular, national courts, to take the advisory opinion, in interpreting and applying domestic law, which is, ultimately, going to be where the rubber hits the road. So my expectations turn on the nature and generality of the opinion that the court is able to give. But where the questions posed are so general, I would be concerned that the answers may also be rather general and that limits my expectations.

CB: You mentioned the state of the science as being very important. We know that the court met with a delegation of IPCC [Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change] authors and I gather there’s some sort of question mark about the procedure used to do that?

PS: The normal process is that if scientists are going to provide information to the judges, it would be in the form of submissions made in writing, or in open court, publicly and transparently. A procedure in which the judges hear privately from any person, however authoritative – and the IPCC is authoritative – is unusual. It’s unorthodox. It does raise questions. We don’t know who attended. We don’t know what they said. We don’t know what the exchanges were with the judges. I have to assume that it was done by the judges, at their request, as a way of informing themselves on the state of science, which is understandable. But the more usual way for this to happen would be, as I said, in written submissions made to the court and in open submissions made already in the courtroom. So it is unusual.

CB: You mentioned already, there’s more than 100 submissions from countries and international organisations. And we’ve obviously got these two weeks of hearings, with some of those same entities making oral statements. How significant are those submissions in terms of shaping the advisory opinion of the court?

PS: My experience before the court, having been involved in a number of cases involving advisory opinions and contentious cases, is that the written pleadings are very important in setting out the generality of the arguments and the totality of the arguments. And, essentially, what you see is a narrowing down. There are essentially three rounds. The first round is the first written statement of the participating states and international organisations. Then they have a second written round, which tends to narrow down the issues and be responsive to the first round of others. And then you’ve got the oral arguments, which are limited, of course, to half an hour for each participant. And so it’s a real narrowing down and homing in. Essentially, what the oral arguments are doing is signaling to the judges what the states participating think are the most significant issues. That’s why the oral phase is very important, because it basically concentrates the issues down to the most significant and narrow set of issues. And so it gives the judges a sense of what states think are the most important issues to be addressed. Secondly, it provides states with an opportunity to hear what responses each state has made to the written submissions of other states. So the oral phase is significant.

CB: If you were going to make a bet, which way would you say the court would go on that key question of whether it’s just the [UN] climate regime that gives rise to obligations [on states], or whether there could be obligations from other parts of the law?

PS: I think the court will proceed very carefully. I don’t think it will want to close the door to the application of other rules of international law. Rather, as the International Tribunal for the Law of the Sea did, which opened the door to the application of the Law of the Sea Convention to the issue of climate change – and opened it quite widely. I don’t know precisely where the court will go. But I would be surprised if they said general international law does not govern issues related to climate change.

The interesting area to read, in what they say, will be the relationship between the general rules and the treaty rules. I mean, the broader issue here is that, essentially, the legislative system has broken down. The states have been unable to legislate effectively and efficiently to address the issues related to climate change. And so what has happened is that a group of states have essentially gone to the General Assembly and said: “The legislative system is broken down. Let’s now ask the judges to step in and tell us what the applicable principles and rules are.” The difficulty that that poses for the judges, who will be conscious that the legislative system has not delivered, is that it’s not the function of judges to legislate. The function of judges is limited to interpreting the law and applying it to the facts, to identify the existence of rules and then applying them to the facts. So I would have thought the instinct of the judges will be to do something, but not to want to overstep the proper boundaries on the judicial function. And that’s a difficult challenge for the judges that they find themselves in.

[It is] a very delicate and difficult situation in the face of, on the one hand, the urgent need for action, and, on the other hand, the failure of states, essentially, to deal with the situation and act as the scientists tell us is needed. I don’t know whether you’ve been through all the different pleadings. I drafted the pleadings for Mauritius – I’m speaking here in a personal capacity. Mauritius decided not to participate in the oral hearings, but you can go on to the Mauritius statement and, if you look at the second Mauritius statement filed in August, you’ll find attached to it as an annex, a report by Prof James Hansen, one of the world’s leading scientists. And that really indicates, with crystal clarity, the urgency of the situation. He’s one of the world’s leading scientists on this issue and that’s the kind of submission that could concentrate the minds of the judges and, I think, impel them to want to go as far as they can. But they’ll be acutely conscious of the limits of judicial function. And, of course, you know, some countries like the UK are basically saying, butt out, leave it to the treaty negotiators, leave it to the treaty system. And the US has said essentially the same thing yesterday. So, it’s a tough situation for the judges.

An abridged version of this interview was published in DeBriefed, Carbon Brief’s weekly email newsletter. Sign up for free.

The interview was conducted by Simon Evans via phone on 5 December 2024.

The post Interview: Prof Philippe Sands on UN court’s landmark climate-change hearing appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Interview: Prof Philippe Sands on UN court’s landmark climate-change hearing

Climate Change

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

The country’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas benefited from what critics say is a questionable IRS interpretation of tax credits.

Cheniere Energy, the largest producer and exporter of U.S. liquefied natural gas, received $370 million from the IRS in the first quarter of 2026, a payout that shipping experts, tax specialists and a U.S. senator say the company never should have received.

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

Climate Change

DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Absolute State of the Union

‘DRILL, BABY’: US president Donald Trump “doubled down on his ‘drill, baby, drill’ agenda” in his State of the Union (SOTU) address, said the Los Angeles Times. He “tout[ed] his support of the fossil-fuel industry and renew[ed] his focus on electricity affordability”, reported the Financial Times. Trump also attacked the “green new scam”, noted Carbon Brief’s SOTU tracker.

COAL REPRIEVE: Earlier in the week, the Trump administration had watered down limits on mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants, reported the Financial Times. It remains “unclear” if this will be enough to prevent the decline of coal power, said Bloomberg, in the face of lower-cost gas and renewables. Reuters noted that US coal plants are “ageing”.

OIL STAY: The US Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments brought by the oil industry in a “major lawsuit”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper said the firms are attempting to head off dozens of other lawsuits at state level, relating to their role in global warming.

SHIP-SHILLING: The Trump administration is working to “kill” a global carbon levy on shipping “permanently”, reported Politico, after succeeding in delaying the measure late last year. The Guardian said US “bullying” could be “paying off”, after Panama signalled it was reversing its support for the levy in a proposal submitted to the UN shipping body.

Around the world

- RARE EARTHS: The governments of Brazil and India signed a deal on rare earths, said the Times of India, as well as agreeing to collaborate on renewable energy.

- HEAT ROLLBACK: German homes will be allowed to continue installing gas and oil heating, under watered-down government plans covered by Clean Energy Wire.

- BRAZIL FLOODS: At least 53 people died in floods in the state of Minas Gerais, after some areas saw 170mm of rain in a few hours, reported CNN Brasil.

- ITALY’S ATTACK: Italy is calling for the EU to “suspend” its emissions trading system (ETS) ahead of a review later this year, said Politico.

- COOKSTOVE CREDITS: The first-ever carbon credits under the Paris Agreement have been issued to a cookstove project in Myanmar, said Climate Home News.

- SAUDI SOLAR: Turkey has signed a “major” solar deal that will see Saudi firm ACWA building 2 gigawatts in the country, according to Agence France-Presse.

$467 billion

The profits made by five major oil firms since prices spiked following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine four years ago, according to a report by Global Witness covered by BusinessGreen.

Latest climate research

- Claims about the “fingerprint” of human-caused climate change, made in a recent US Department of Energy report, are “factually incorrect” | AGU Advances

- Large lakes in the Congo Basin are releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere from “immense ancient stores” | Nature Geoscience

- Shared Socioeconomic Pathways – scenarios used regularly in climate modelling – underrepresent “narratives explicitly centring on democratic principles such as participation, accountability and justice” | npj Climate Action

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

The constituency of Richard Tice MP, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of Reform UK, is the second-largest recipient of flood defence spending in England, according to new Carbon Brief analysis. Overall, the funding is disproportionately targeted at coastal and urban areas, many of which have Conservative or Liberal Democrat MPs.

Spotlight

Is there really a UK ‘greenlash’?

This week, after a historic Green Party byelection win, Carbon Brief looks at whether there really is a “greenlash” against climate policy in the UK.

Over the past year, the UK’s political consensus on climate change has been shattered.

Yet despite a sharp turn against climate action among right-wing politicians and right-leaning media outlets, UK public support for climate action remains strong.

Prof Federica Genovese, who studies climate politics at the University of Oxford, told Carbon Brief:

“The current ‘war’ on green policy is mostly driven by media and political elites, not by the public.”

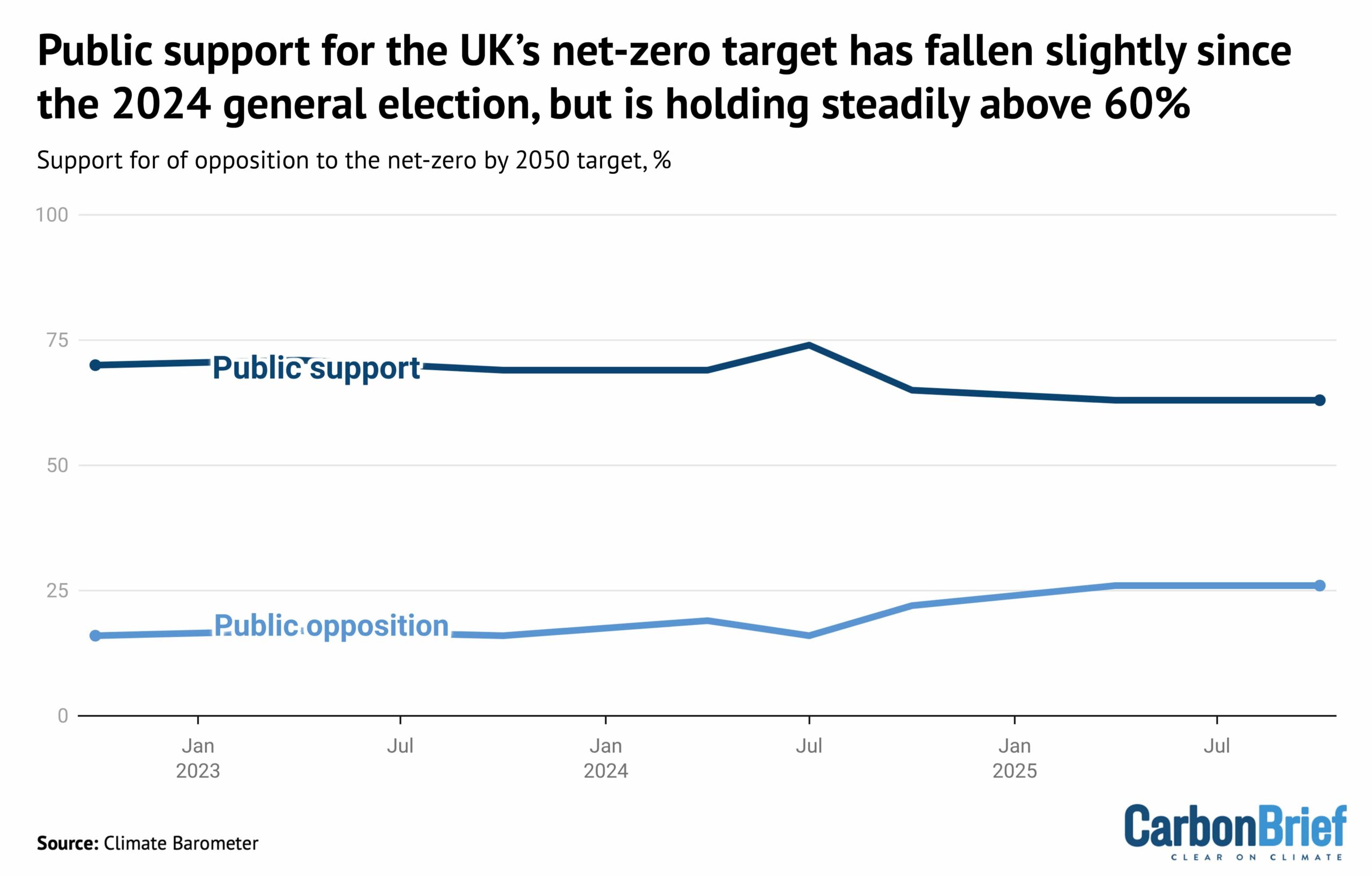

Indeed, there is still a greater than two-to-one majority among the UK public in favour of the country’s legally binding target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, as shown below.

Steve Akehurst, director of public-opinion research initiative Persuasion UK, also noted the growing divide between the public and “elites”. He told Carbon Brief:

“The biggest movement is, without doubt, in media and elite opinion. There is a bit more polarisation and opposition [to climate action] among voters, but it’s typically no more than 20-25% and mostly confined within core Reform voters.”

Conservative gear shift

For decades, the UK had enjoyed strong, cross-party political support for climate action.

Lord Deben, the Conservative peer and former chair of the Climate Change Committee, told Carbon Brief that the UK’s landmark 2008 Climate Change Act had been born of this cross-party consensus, saying “all parties supported it”.

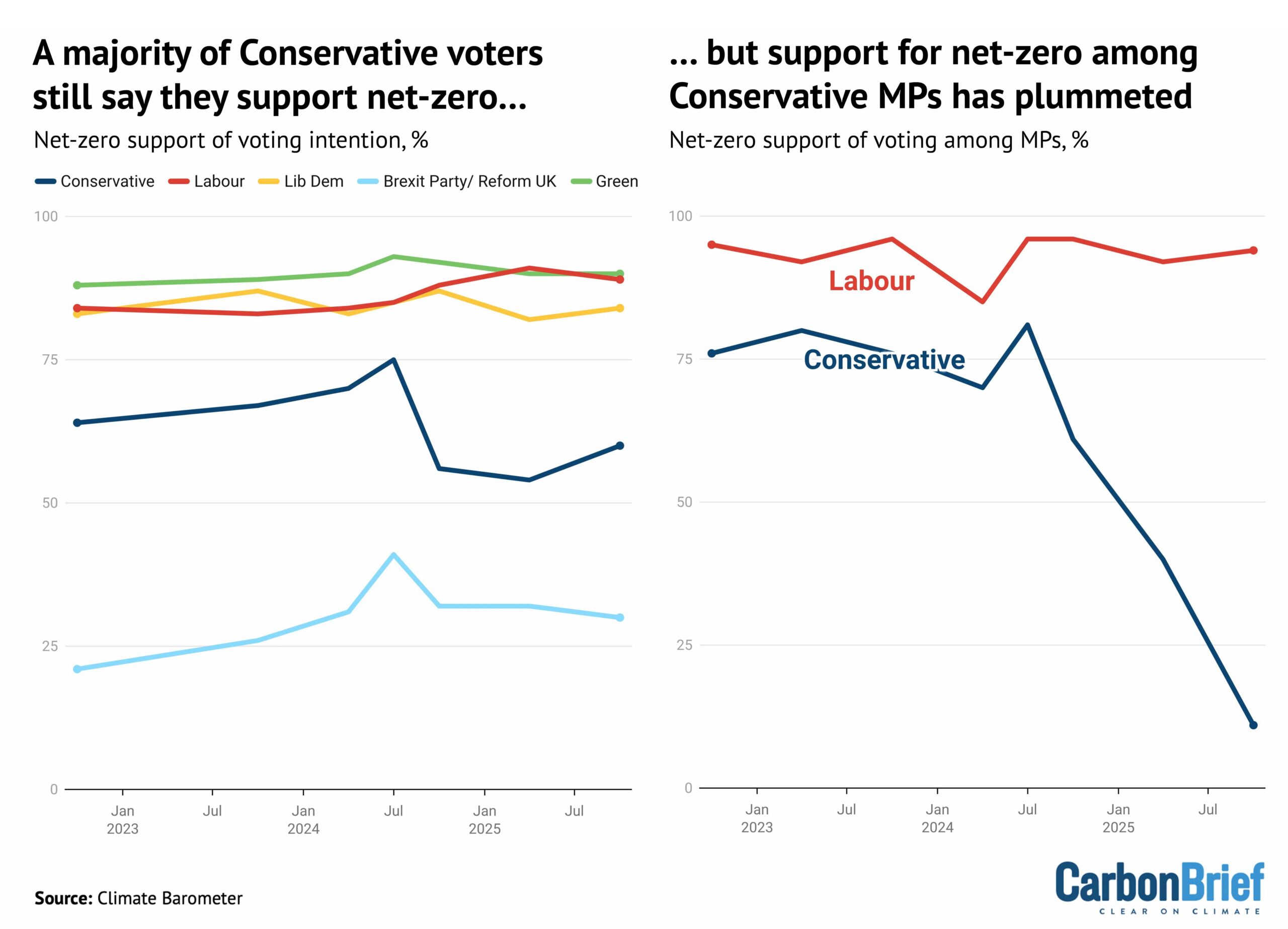

Since their landslide loss at the 2024 election, however, the Conservatives have turned against the UK’s target of net-zero emissions by 2050, which they legislated for in 2019.

Curiously, while opposition to net-zero has surged among Conservative MPs, there is majority support for the target among those that plan to vote for the party, as shown below.

Dr Adam Corner, advisor to the Climate Barometer initiative that tracks public opinion on climate change, told Carbon Brief that those who currently plan to vote Reform are the only segment who “tend to be more opposed to net-zero goals”. He said:

“Despite the rise in hostile media coverage and the collapse of the political consensus, we find that public support for the net-zero by 2050 target is plateauing – not plummeting.”

Reform, which rejects the scientific evidence on global warming and campaigns against net-zero, has been leading the polls for a year. (However, it was comfortably beaten by the Greens in yesterday’s Gorton and Denton byelection.)

Corner acknowledged that “some of the anti-net zero noise…[is] showing up in our data”, adding:

“We see rising concerns about the near-term costs of policies and an uptick in people [falsely] attributing high energy bills to climate initiatives.”

But Akehurst said that, rather than a big fall in public support, there had been a drop in the “salience” of climate action:

“So many other issues [are] competing for their attention.”

UK newspapers published more editorials opposing climate action than supporting it for the first time on record in 2025, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Global ‘greenlash’?

All of this sits against a challenging global backdrop, in which US president Donald Trump has been repeating climate-sceptic talking points and rolling back related policy.

At the same time, prominent figures have been calling for a change in climate strategy, sold variously as a “reset”, a “pivot”, as “realism”, or as “pragmatism”.

Genovese said that “far-right leaders have succeeded in the past 10 years in capturing net-zero as a poster child of things they are ‘fighting against’”.

She added that “much of this is fodder for conservative media and this whole ecosystem is essentially driving what we call the ‘greenlash’”.

Corner said the “disconnect” between elite views and the wider public “can create problems” – for example, “MPs consistently underestimate support for renewables”. He added:

“There is clearly a risk that the public starts to disengage too, if not enough positive voices are countering the negative ones.”

Watch, read, listen

TRUMP’S ‘PETROSTATE’: The US is becoming a “petrostate” that will be “sicker and poorer”, wrote Financial Times associate editor Rana Forohaar.

RHETORIC VS REALITY: Despite a “political mood [that] has darkened”, there is “more green stuff being installed than ever”, said New York Times columnist David Wallace-Wells.

CHINA’S ‘REVOLUTION’: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast reported from China on the “green energy revolution” taking place in the country.

Coming up

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean, Brasília

- 3 March: UK spring statement

- 4-11 March: China’s “two sessions”

- 5 March: Nepal elections

Pick of the jobs

- The Guardian, senior reporter, climate justice | Salary: $123,000-$135,000. Location: New York or Washington DC

- China-Global South Project, non-resident fellow, climate change | Salary: Up to $1,000 a month. Location: Remote

- University of East Anglia, PhD in mobilising community-based climate action through co-designed sports and wellbeing interventions | Salary: Stipend (unknown amount). Location: Norwich, UK

- TABLE and the University of São Paulo, Brazil, postdoctoral researcher in food system narratives | Salary: Unknown. Location: Pirassununga, Brazil

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

Seven Pacific island nations say they will demand heftier levies on global shipping emissions if opponents of a green deal for the industry succeed in reopening negotiations on the stalled accord.

The United States and Saudi Arabia persuaded countries not to grant final approval to the International Maritime Organization’s Net-Zero Framework (NZF) in October and they are now leading a drive for changes to the deal.

In a joint submission seen by Climate Home News, the seven climate-vulnerable Pacific countries said the framework was already a “fragile compromise”, and vowed to push for a universal levy on all ship emissions, as well as higher fees . The deal currently stipulates that fees will be charged when a vessel’s emissions exceed a certain level.

“For many countries, the NZF represents the absolute limit of what they can accept,” said the unpublished submission by Fiji, Kiribati, Vanuatu, Nauru, Palau, Tuvalu and the Solomon Islands.

The countries said a universal levy and higher charges on shipping would raise more funds to enable a “just and equitable transition leaving no country behind”. They added, however, that “despite its many shortcomings”, the framework should be adopted later this year.

US allies want exemption for ‘transition fuels’

The previous attempt to adopt the framework failed after governments narrowly voted to postpone it by a year. Ahead of the vote, the US threatened governments and their officials with sanctions, tariffs and visa restrictions – and President Donald Trump called the framework a “Green New Scam Tax on Shipping”.

Since then, Liberia – an African nation with a major low-tax shipping registry headquartered in the US state of Virginia – has proposed a new measure under which, rather than staying fixed under the NZF, ships’ emissions intensity targets change depending on “demonstrated uptake” of both “low-carbon and zero-carbon fuels”.

The proposal places stringent conditions on what fuels are taken into consideration when setting these targets, stressing that the low- and zero-carbon fuels should be “scalable”, not cost more than 15% more than standard marine fuels and should be available at “sufficient ports worldwide”.

This proposal would not “penalise transitional fuels” like natural gas and biofuels, they said. In the last decade, the US has built a host of large liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals, which the Trump administration is lobbying other countries to purchase from.

The draft motion, seen by Climate Home News, was co-sponsored by US ally Argentina and also by Panama, a shipping hub whose canal the US has threatened to annex. Both countries voted with the US to postpone the last vote on adopting the framework.

The IMO’s Panamanian head Arsenio Dominguez told reporters in January that changes to the framework were now possible.

“It is clear from what happened last year that we need to look into the concerns that have been expressed [and] … make sure that they are somehow addressed within the framework,” he said.

Patchwork of levies

While the European Union pushed firmly for the framework’s adoption, two of its shipping-reliant member states – Greece and Cyprus – abstained in October’s vote.

After a meeting between the Greek shipping minister and Saudi Arabia’s energy minister in January, Greece said a “common position” united Greece, Saudi Arabia and the US on the framework.

If the NZF or a similar instrument is not adopted, the IMO has warned that there will be a patchwork of differing regional levies on pollution – like the EU’s emissions trading system for ships visiting its ports – which will be complicated and expensive to comply with.

This would mean that only countries with their own levies and with lots of ships visiting their ports would raise funds, making it harder for other nations to fund green investments in their ports, seafarers and shipping companies. In contrast, under the NZF, revenues would be disbursed by the IMO to all nations based on set criteria.

Anais Rios, shipping policy officer from green campaign group Seas At Risk, told Climate Home News the proposal by the Pacific nations for a levy on all shipping emissions – not just those above a certain threshold – was “the most credible way to meet the IMO’s climate goals”.

“With geopolitics reframing climate policy, asking the IMO to reopen the discussion on the universal levy is the only way to decarbonise shipping whilst bringing revenue to manage impacts fairly,” Rios said.

“It is […] far stronger than the Net-Zero Framework that is currently on offer.”

The post Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen appeared first on Climate Home News.

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits