The Brazilian COP30 presidency has published a “Baku to Belém roadmap” on how climate finance could be scaled up to “at least $1.3tn” a year by 2035.

The idea for the roadmap was a late addition to the outcome of COP29 last year, following disappointment over the formal $300bn-per-year climate-finance goal agreed in Baku.

The new document, published ahead of the UN climate talks in Belém, Brazil, says it is not designed to create new financing schemes or mechanisms.

Instead, the roadmap says it provides a “coherent reference framework on existing initiatives, concepts and leverage points to facilitate all actors coming together to scale up climate finance in the short to medium term”.

It details suggested actions across grants, concessional finance, private finance, climate portfolios, capital flows and more, designed to drive up climate finance over the next decade.

Despite geopolitical uncertainty, there is hope that this roadmap can lay out a pathway to the “trillions” in climate finance that developing countries say they need to meet their climate targets.

Countries have divergent views on how to get there, but some notable trends have emerged from the roadmap, which was spearheaded by the Azerbaijani and Brazilian COP presidencies.

Below, Carbon Brief details what the Baku to Belém roadmap is, why it was launched and what the key points within it are.

- Why was the ‘Baku to Belém roadmap’ launched?

- What is the goal of the roadmap?

- What are different countries’ views on climate finance?

- What are the solutions that the roadmap has identified?

- What happens next?

Why was the ‘Baku to Belém roadmap’ launched?

A mounting body of evidence shows that developing countries will need trillions of dollars in the coming years if they are to achieve their climate goals.

While much of this finance will likely be sourced domestically within those countries, a large slice is expected to come from international actors.

This climate finance is part of the “grand bargain” at the heart of the Paris Agreement, whereby developing countries agree to set more ambitious climate plans if they receive financial support from developed countries.

Ahead of COP29, developing countries hoped that the post-2025 climate finance target – known as the new collective quantified goal (NCQG) – would reflect their full “needs and priorities”, as set out in the Paris Agreement.

They also pushed for developed-country parties such as the EU, the US and Japan to contribute a large portion of this finance, preferably on favourable terms such as grants.

They were left largely disappointed, with a final target that fell well short of what many developing countries had been proposing.

The central target agreed at COP29 was “at least” $300bn a year by 2035, with an expectation that developed countries would “take the lead” in providing these funds from “a wide variety of sources”, including private finance.

This goal – which was effectively the successor to the previous $100bn-per-year target – was far short of what developing countries had wanted. However, another key part of the text agreed in Baku alludes to their ambitions, with a loose request that “all actors” scale up finance to at least $1.3tn per year by 2035:

“[The COP] calls on all actors to work together to enable the scaling up of financing to developing country parties for climate action from all public and private sources to at least $1.3tn per year by 2035.”

In contrast to the $300bn target, this $1.3tn figure, which first appeared in a proposal by the African Group in 2021, reflects developing-country demands and needs. It also aligns with influential analysis of developing-country needs by the Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance (IHLEG).

Yet, this part of the text lacked binding language and detail on who precisely would be responsible for providing these funds. It has therefore been described by civil-society groups as more of an aspirational “call to action” than a target.

(“Calls on” is the weakest form of words in which UN legal texts can make a request.)

However, the COP29 text contained another relevant decision, added as negotiations drew to a close. It mentioned a “Baku to Belém roadmap to $1.3tn” – a report that could flesh out ways to scale up finance further and help developing countries achieve their climate targets.

The Azerbaijani COP29 presidency and the incoming Brazilian presidency were tasked with assembling this roadmap ahead of COP30 in 2025.

In the months that followed, the presidencies engaged with governments, civil-society groups, businesses and other relevant actors. They gathered information to build a “library of knowledge and best practices”, which could boost climate finance for developing countries.

What is the goal of the roadmap?

The roadmap comes at a difficult time for climate finance, with a particularly “bleak” outlook for public funding from developed countries. Major donors – particularly the US – have made large cuts to their aid budgets, threatening climate spending overseas.

At the same time, private investment has also faltered, with successive economic shocks raising the cost of capital for clean-energy projects in developing countries.

For years, finance experts and development leaders have talked of a “billions to trillions” agenda, suggesting that public money could help to “mobilise” trillions of dollars of private investments that could be used to build low-carbon infrastructure in the global south.

Yet, the “billions to trillions” concept has also faced growing scrutiny, with even the World Bank chief economist Indermit Gill branding it “a fantasy”. Critics have highlighted wider issues constraining developing countries, such as high levels of debt.

The NCQG text from COP29 set out the roadmap’s overarching goal of scaling up annual climate finance to $1.3tn, through means including “grants, concessional and non-debt-creating instruments, and measures to create fiscal space”.

On the current trajectory, financial sources potentially covered by the target could hit around $427bn for developing countries a year by 2035, less than a third of the goal, according to analysis by the thinktank NRDC.

Achieving $1.3tn of finance relies on what one report calls “yet-to-be-defined mechanisms”, which go beyond the ones covered by the $300bn target.

Countries and other relevant parties were asked by the presidencies for their views on “short-term” – actions by 2028 and “medium-to-long term” actions beyond 2028 that could ramp up finance further. They were asked about new sources of finance and thoughts on scaling up adaptation finance, in particular.

There have already been numerous ideas and programmes put forward for scaling up international climate finance. These include G20-led reforms of the multilateral development banks (MDBs), this year’s International Conference on Financing for Development, as well as UN sovereign debt restructuring efforts.

Accordingly, the Baku to Belém roadmap was also given a remit to “tak[e] into account relevant multilateral initiatives as appropriate”. Parties were also asked for suggestions of organisations and initiatives that should be involved.

Rebecca Thissen from Climate Action Network (CAN) International tells Carbon Brief:

“The roadmap could support the UNFCCC to be sending strong signals to the international community…But also using the convening power that the UNFCCC could have, so bringing those different actors to the table in a more structured and predictable way.”

What are different countries’ views on climate finance?

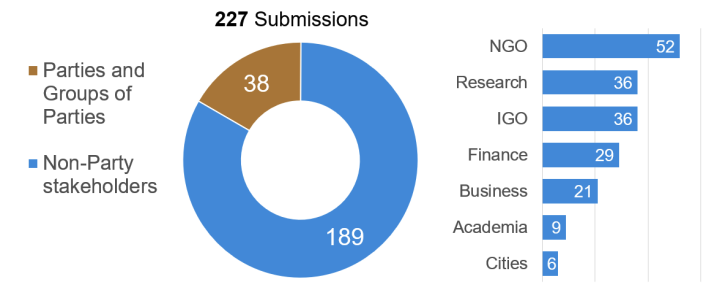

There were over 227 submissions into the Baku to Belém roadmap, including 38 from countries and party groupings. The remainder came mainly from NGOs, businesses, financial experts and researchers, as shown in the figure below.

The submissions partly reflect what the thinktank C2ES describes as the “pockmarked baggage of the climate finance negotiations”, with many parties demonstrating the same entrenched, often opposing views on climate finance that they have held for decades.

Carbon Brief has captured the submissions by countries and party groupings in the interactive table below, comparing their views on key issues.

There is broad agreement among countries that the roadmap should not reopen the NCQG discussions or involve a new, negotiated outcome at COP30.

However, some parties still call for more accountability in achieving the existing goals.

Latin American countries within the AILAC grouping call for the roadmap to “define concrete milestones for scaling up climate finance”. Egypt goes further, proposing that developed countries alone commit “at least $150bn annually in public concessional finance by 2028”, mainly as grants.

A key divergence in submissions is on which governments and institutions, precisely, should be responsible for scaling finance up to $1.3tn.

Several developing-country groups stress the importance of centring developed countries as the primary contributors, referencing Article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement.

The Like-Minded Developing Countries (LMDCs) group, which includes India, China and Saudi Arabia, states that “the roadmap must place Article 9.1 as its central pillar”. The G77 and China – a group representing all developing countries – stresses the “additional role developed countries will play in the context of Article 9.1, which is additional to the $300bn”.

Meanwhile, many developed countries focus on what Canada refers to as “a necessary broadening of climate finance” within the roadmap. In practice, this often amounts to a greater push for private finance, as well as “innovative” new sources such as global levies.

While developing countries do not often outright oppose such sources, some of them propose tighter limits. For example, China says “purely commercial investment flows should not be included” in the $1.3tn, which should only count funds “mobilised through public interventions”.

A related dispute centres on the roadmap’s scope, with the EU suggesting it should “extend beyond the UNFCCC framework”.

Parties such as India reject the idea of involving other multilateral fora, such as the G20. This would involve moving beyond the UN climate process, where developed countries have traditionally been the ones responsible for channelling climate finance.

The submissions also show notable differences among developing-country groupings. On the topic of defining what should be counted as “climate finance”, the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) opposes the inclusion of funding for fossil-fuel projects, while the Arab Group says it does not support “any exclusionary criteria”.

There is coalescence between parties around other issues, albeit with various subtle differences.

Areas of broad agreement include the importance of more funding for climate adaptation, dealing with “barriers” to funding in developing countries and improving the transparency of climate-finance provision.

The roadmap details some of the potential sources of finance identified within the submissions.

This includes direct budget contributions, which the submissions suggest could generate an additional $197bn in financing; improved rechanneling and new issuances of special drawing rights ($100-500bn per year); carbon pricing ($20-4,900bn, dependent on rate and geographies); and fees on aviation or maritime transport($4-223bn).

Additionally, a range of taxes were identified as candidates for raising new climate finance. These include taxes on specific goods such as luxury fashion, technology and military goods ($34-112bn), financial transactions taxes ($105-327bn), minimum corporate taxes ($165-540bn) and wealth taxes ($200-1,364bn).

In a statement, Rebecca Newsom, global political expert at Greenpeace International, said:

“It’s notable that the roadmap recognises new taxes and levies as key to unlocking public climate finance. Given reported profits from just five international oil and gas giants over the last decade reached almost $800bn, taxing fossil fuel corporations is clearly a huge opportunity to overcome national fiscal constraints.

“The roadmap’s recognition that the UN tax convention provides an opportunity to raise new sources of concessional climate finance is also highly welcome, and is an opportunity governments must now seize.”

What are the solutions that the roadmap has identified?

The roadmap sets out “five action fronts” for reaching $1.3tn by 2035.

These are designed to “help deliver on the at-least-$1.3tn aspiration by strengthening supply, making demand more strategic, and accelerating access and transparency”.

The report titles these five action fronts as “replenishing, rebalancing, rechanneling, revamping and reshaping”.

Within each of these, the roadmap lays out key points to help “transform scientific warning into a global blueprint for cooperation and tangible results”.

The first, “replenishing”, refers to grants, concessional finance and low-cost capital, including multilateral climate funds and MDBs.

It notes that there is a “growing role” for MDBs in advancing climate action, as well as a need for developed countries to achieve “manyfold increases in the delivery of grants and concessional climate finance, including through bilateral and multilateral channels”.

Access to grants and concessional finance is a key enabling factor for an “efficient” flow of public funding, the roadmap notes.

The roadmap calls for coordination in the international finance system, bilateral finance that is concessional and low-cost, multilateral climate funds, innovative sources of concessional finance with simplified access pathways and more.

This coordination could be key, with Sarah Colenbrander, director of ODI’s climate and sustainability programme, telling Carbon Brief:

“The bigger risk is probably that some countries will allocate their climate finance differently, so that they can report more money going out the door without a commensurate increase in fiscal effort. For example, they might shift from grants to concessional loans, and from concessional loans to market-rate loans. If the money will be repaid, there is less lift for taxpayers at home.

“Alternatively, countries might focus on using public finance to mobilise private finance that can also count towards the $300bn goal. Private finance has a very important role to play in both mitigation and adaptation, but it is very unlikely to meet the needs of the most vulnerable communities, given their high adaptation investment needs and very limited ability to pay.”

In particular, the roadmap suggests MDBs “intensify their engagement on climate finance through a strategic approach that recognises and amplifies their catalytic role in providing and mobilising capital”.

Second, “rebalancing” refers to fiscal space and debt sustainability. The roadmap calls on creditor countries, the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and MDBs to work together to “alleviate onerous debt burdens faced by developing countries”.

The roadmap notes that external debt servicing costs of developing countries have more than doubled since 2014, to $1.7tn per year in 2023.

Developing countries’ net interest payments on public debt reached $921bn in 2024, a 10% increase compared to 2023, it adds.

The roadmap notes the need to “remove barriers and address disenablers faced by developing countries in financing climate action”. It adds that developing countries face at least two- to four-times the borrowing costs of developed countries.

It points to a number of “promising” solutions already being implemented, such as climate-resilient debt clauses and “debt-for-climate swaps” and debt restructuring.

In particular, MDBs, the IMF, UN agencies and regional UN economic commissions could work together to create a “one-stop shop” for assistance in these areas, the roadmap says.

Third, “rechannelling” refers to “transformative” private finance and affordable cost of capital.

It notes that mobilisation of private finance has been “stubborn to scale”: The level of private finance leveraged by official development interventions has grown by 7% per year from 2016 to 2019 and then 16% per year from 2020 to 2023, to reach $46bn.

The roadmap says that “blended finance” can play a role in scaling up climate finance and that private finance for the implementation of “nationally determined contributions” to cutting global emissions (NDCs) and national adaptation plans (NAPs) has “significant potential for growth”.

“Innovative instruments” are listed as a key approach to improving private finance, including “catalytic equity”, guarantees, foreign exchange risk management, securitisation platforms and more.

To support this, the roadmap calls for target-setting and data transparency, along with increasing, coordinating and harmonising guarantee offerings and channelling concessional finance into long-term foreign exchange hedging facilities, along with other actions.

Relying heavily on private finance could pose a risk, Jan Kowalzig, senior policy adviser for climate at Oxfam Germany, tells Carbon Brief, adding:

“The much larger problem, however, is the plan to massively rely on private finance in the future. While private finance has a key role to play to transform economies, [it] cannot replace much-needed public finance, especially for adaptation and for responding to loss and damage.

“Interventions in these sectors often do not generate return to satisfy investors’ expectations. Forcing projects to become profitable can come at great social cost for frontline communities struggling to survive in the worsening climate crisis.”

The roadmap suggests financial institutions move towards “originate-to-distribute” and “originate-to-share” business models, support the development of climate-aligned domestic financial systems and expand investor bases and diverse sources of capital, amongst other proposals.

Fourth is “revamping”, referring to capacity and coordination for scaled climate portfolios. This “demands institutions to manage risks locally, develop project pipelines, ensure country ownership and track progress and impact”.

It notes that “whole-of-government” approaches to the transition can be strengthened, with NDCs and NAPs integrated throughout national investment strategies. Additionally, it points to country-led coordination or platforms as a route for improving investment.

The roadmap suggests readiness support and project preparation as routes to “revamp” climate finance, alongside support to scale, coordinate and tailor capacity building, the development of country platforms and the provision of “predictable and flexible support for investment frameworks”.

The final “R” is “reshaping”, focused on systems and structures for capital flows. It highlights a number of barriers that still remain for capital flows through developing countries, including outdated clauses in investment treaties.

It recommends prudential regulation, interoperability of taxonomies, climate disclosure frameworks and investment treaties, as key actions to support the reshaping of capital flows.

Additionally, the roadmap suggests that credit rating agencies further refine their methodologies, that jurisdictions adopt voluntary disclosure of climate-related financial risks of financial institutions and that climate stress-test requirements are gradually embedded in supervisory reviews and bank risk management.

Beyond the “five [finance] action fronts”, the roadmap sets out five thematic areas, noting that “where and how finance is directed” matters.

These are: adaptation and loss and damage; clean-energy access and transitions; nature and supporting its guardians; agriculture and food systems; and just transitions.

Within each, it sets out some of the key challenges and suggests routes for financial support.

What happens next?

The Baku to Belem roadmap is not a formal part of COP30 negotiations, but there will be a major launch event at the summit.

Beyond that, the final section of the roadmap sets out that this is the “beginning [of] the journey”. It and details suggested short-term contributions (2026-2028), to serve as “initial, practical steps to inform and guide the early implementation of the roadmap”.

This includes the Azerbaijani and Brazilian presidencies convening an expert group tasked with refining data and developing “concrete financing pathways” to get to $1.3bn in 2035. This will build on the action fronts set out in the roadmap, with the first such report due by October 2026.

Throughout 2026, the presidencies will convene dialogue sessions with parties and stakeholders to discuss how to progress the action fronts over the medium to long term.

The roadmap suggests that to improve predictability, developed countries “could consider” working together on a delivery plan to outline how they expect to achieve the at-least $300bn goal by 2030, as well as other elements of the NCQG.

Additional suggestions in the roadmap are listed in the table below.

(Notably, almost all of these suggestions are made using loose, voluntary language. For example, the roadmap says that developed countries “could” create a delivery plan for their NCQG pathways.)

| Who | What | When |

|---|---|---|

| COP29 and COP30 presidencies | Convene an expert group to develop “concrete financing pathways” | October 2026 |

| COP29 and COP30 presidencies | Convene dialogue sessions with parties and stakeholders | 2026 |

| Developed countries | Creating a delivery plan to set out intended contributions and pathways for NCQG targets | End of 2026 |

| Parties to the Paris Agreement | Request the Standing Committee on Finance to provide an aggregate view on pathways for NCQG | 2027 |

| Governments | Request UN entities to examine and review collaboration options | October 2026 |

| Multilateral climate funds | Report annually on the implementation of their “operational framework” on complementarity and coherence, to enhance cross-fund collaboration. | Annually |

| Multilateral climate funds | Develop monitoring and reporting frameworks and coordination plans, explaining their operations by region, topic and sector | October 2027 |

| Multilateral development banks | Collective report on achieving a new aspirational climate finance target for 2035 | October 2027 |

| Multilateral development banks | Adopt “explicit, ambitious and transparent targets for adaptation and private capital mobilisation” | October 2027 |

| International Monetary Fund | Conduct an assessment of the costs, benefits and feasibility of a new issuance of “special drawing rights” | October 2027 |

| UN regional economic commissions | Develop a study on the potential for expanding debt-for-climate, debt-for-nature and sustainability-linked finance | End of 2027 |

| UNSG-convened working group | Propose a consolidated set of voluntary principles on responsible sovereign borrowing and lending. | October 2026 |

| Crediting rating agencies | Develop a structured dialogue platform with ministries of finance to make progress on refinements to credit rating methodologies. | October 2027 |

| Philanthropies | Expand funding of knowledge hubs | October 2026 |

| UN treaty executive secretariats | Develop a joint report with proposals on economic instruments to support co-benefits and efficiencies | End of 2027 |

| Insurance Development Forum and the V20 | Establish a plan for achieving cheaper and more robust insurance and pre-arranged finance mechanisms for climate disasters | October 2026 |

| Financial Stability Board, the Basel Committee on Banking Supervision and the International Association of Insurance Supervisors | Conduct a joint assessment of whether and how barriers to investment in developing countries could be reduced | October 2027 |

| World’s 100 largest companies | Report annually on how they are contributing towards the implementation of NDCs and NAPs | Annually |

| World’s 100 largest institutional investors | Report annually on how they are contributing towards the implementation of NDCs and NAPs | Annually |

COP29 president Mukhtar Babayev and COP30 president André Aranha Corrêa do Lago conclude in the foreword of the report that while the $1.3bn “journey” is beginning amid “turbulent times”, they are confident that “technological and financial solutions exist”. They add:

“Communities and cities are acting. Families and workers are ready to roll up their sleeves and deliver more action. If resources are strategically redirected and deployed effectively – and if the international financial architecture is reset to fulfil its original purpose of ensuring decent prospects for life – the $1.3tn goal will be an achievable global investment in our present and our future. We are optimistic.”

The post COP30: What does the ‘Baku to Belém roadmap’ mean for climate finance? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

COP30: What does the ‘Baku to Belém roadmap’ mean for climate finance?

Climate Change

Hydrogen emissions are ‘supercharging’ the warming impact of methane

The warming impact of hydrogen has been “overlooked” in projections of climate change, according to authors of the latest “global hydrogen budget”.

The study, published in Nature, is the most comprehensive analysis yet of the global hydrogen cycle, showing how the gas moves between the atmosphere, land and ocean.

Hydrogen has long been recognised as a clean alternative to fossil fuels and an important component of the green energy transition.

However, while hydrogen is not itself a greenhouse gas, rising emissions are “supercharging” the warming effect of methane, the authors say.

Increasing levels of atmospheric hydrogen have led to “indirect” warming of 0.02C over the past decade, the study finds.

The authors say that limiting leaks from future hydrogen fuel projects and rapidly cutting methane emissions will be key to securing benefits from hydrogen as a clean-burning alternative to oil and gas.

The international team of scientists behind the study also produce the annual “global carbon budget”, which saw its 20th edition published last month.

‘Supercharging’ methane

Hydrogen is the lightest and most abundant element in the universe. It is also an explosive gas that contains more energy per unit of weight than fossil fuels.

The gas has long been recognised as a clean alternative to fossil fuels, because it only emits water when burned.

There are many ways to produce hydrogen. It is typically generated in a carbon-intensive process that relies on fossil fuels. However, renewable energy can be used to produce “green hydrogen” with near-zero carbon emissions.

Hydrogen “indirectly” heats the atmosphere through its interactions with other gases. This warming is mainly due to interplay between hydrogen and methane – a potent greenhouse gas that is the second biggest contributor to human-caused global warming after CO2.

This interplay involves molecules in the atmosphere called hydroxyl radicals. These naturally occurring molecules are known as the atmosphere’s “detergents” because they react with certain greenhouse gases, such as methane, converting them into other compounds that do not warm the planet.

Prof Rob Jackson is a scientist at Stanford University and an author on the study. He explains that hydrogen also reacts with hydroxyl radicals, effectively “using up” these detergents and leaving less to react with methane.

This effectively “extends the lifetime” of methane in the atmosphere, Jackson tells Carbon Brief, leading to higher concentrations and greater warming.

There is also a reciprocal effect, where more methane in the atmosphere leads to more hydrogen. This occurs because methane reacts with oxygen in the atmosphere in a process called “oxidation”, which produces hydrogen.

Jackson tells Carbon Brief that interactions between hydrogen and methane have “not really been considered in climate circles”, adding:

“I think people don’t realise that the dominant source of hydrogen in the world today is methane in the atmosphere.”

Overall, the study estimates that increasing levels of hydrogen in the atmosphere led to global warming of 0.02C over 2010-20. This climate impact has been “overlooked”, the researchers say in a press release.

Jackson tells Carbon Brief that although this level of warming “looks fairly small”, it is still “comparable” to the warming caused by emissions of individual countries, such as France.

The hydrogen cycle

The global hydrogen budget brings together a range of observed data and models to quantify sources of hydrogen emissions as well as “sinks”, which absorb the gas from the atmosphere.

The authors find that hydrogen levels in the atmosphere increased from 523 parts per billion (ppb) in 1992 to 543ppb in 2020.

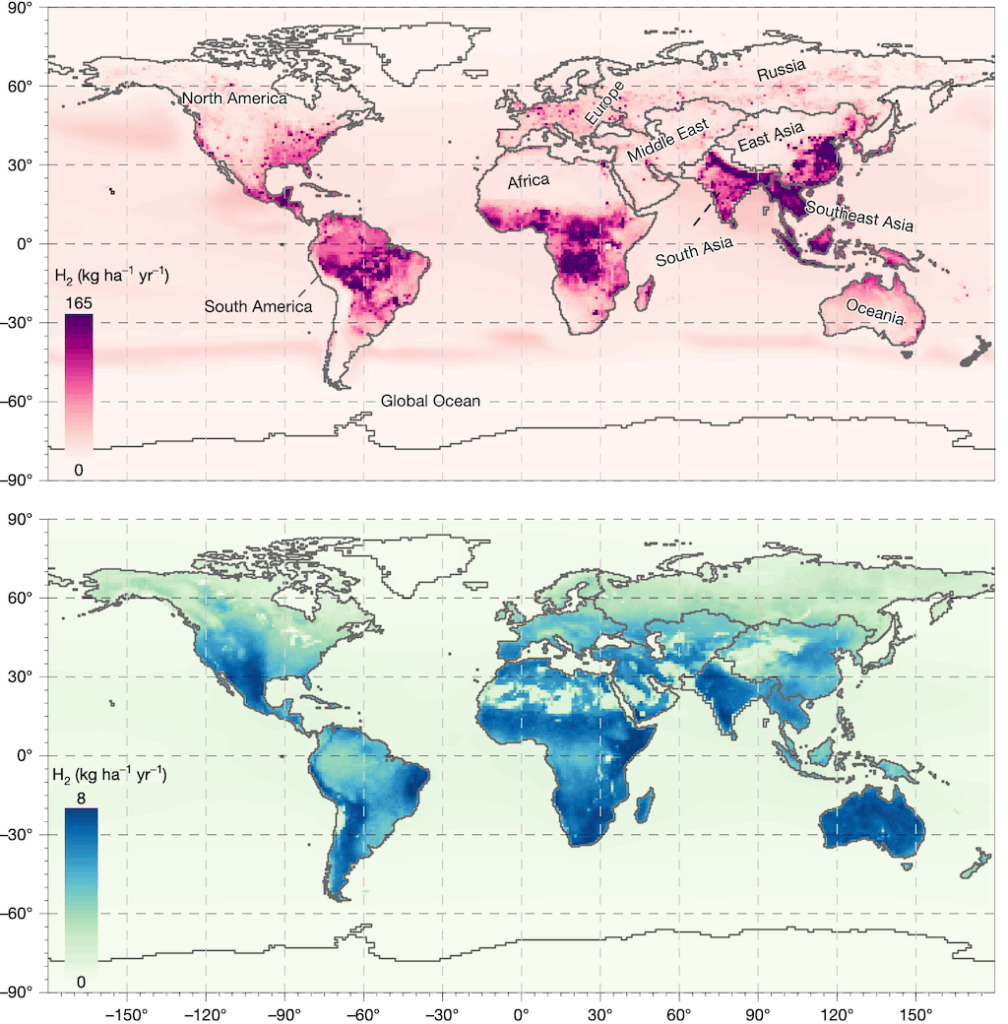

The graphic below shows the main sources (up arrows) and sinks (down arrows) of hydrogen over 2010-20.

As the figure shows, the largest single contributor to rising hydrogen emissions over 2010-20 is from the oxidation of human-produced methane. Methane emissions are on the rise due to human activity, such as from the fossil fuel industry, livestock and waste.

According to the study, 56% of atmospheric hydrogen over 2010-20 was caused by the oxidation of methane and non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs) reacting with oxygen to produce hydrogen.

(NMVOCs are chemicals that are released naturally from vegetation and more rapidly during wildfires. Human-produced emissions of NMVOCs – for example, from oil refineries or car tailpipes – are also on the rise, according to the study.)

The study also points to leakage from industrial hydrogen production as another driver of rising atmospheric hydrogen levels.

Jackson tells Carbon Brief that hydrogen leakage is on the rise “not because manufacturing is getting dirtier, but because we’re making more hydrogen from coal and natural gas”.

Hydrogen can also be produced as an unintentional byproduct from the combustion of fossil fuels. The study finds that these emissions of hydrogen are decreasing.

At the same time, natural sources of hydrogen emissions have not shown any increasing or decreasing trend over time, the authors say.

One of the largest natural sources of hydrogen is through “nitrogen fixing” – a chemical process in which nitrogen is converted into ammonia, which releases hydrogen as a byproduct. This process locks down nitrogen into the soil and ocean, where it is used by plants and algae to grow.

Meanwhile, hydrogen sinks have “increased in response to rising atmospheric hydrogen” over the past three decades, the study says.

Nearly three-quarters of the global hydrogen sink comes from hydrogen getting trapped in soil – for example, by microbes taking in hydrogen to use for energy, or hydrogen seeping into the soil through diffusion.

Dr Zutao Ouyang is an assistant professor at the University of Harvard and lead author on the study. He tells Carbon Brief that soil uptake is “the main mechanism removing hydrogen from the atmosphere”, but adds that it also has “the greatest uncertainty” because there is “not much long-term data” on this component of the hydrogen budget.

Mapped

Drawing on data including observational measurements and emissions inventories, the authors map the sources and sinks of hydrogen and their relative strength.

The maps below show the sources (top) and sinks (bottom) over 1990-2020, where darker colours indicate a stronger source or sink.

The largest “hotspots” for hydrogen emissions are in “south-east and east Asia”, according to the research. More widely, it says that “tropical regions” contribute about 60% of total hydrogen emissions.

The authors explain that these “hotspots” occur because the oxidation of methane and NMVOCs – processes that happen in the atmosphere and produce hydrogen as a byproduct – happen more quickly at higher temperatures.

They also find that these regions have more vegetation, which leads to higher NMVOC emissions.

For emissions related to human activity, east Asia and North America “contributed the most hydrogen emissions from fossil fuel combustion”, the study says, due to the “intensive fossil fuel use”.

Hydrogen emissions due to nitrogen fixation – when plants draw down nitrogen and release hydrogen as a byproduct – are highest in South America. The report links these emissions to the region’s “extensive cultivation” of crops such as soybeans and peanuts.

Dr Maria Sand is a senior researcher at CICERO and was not involved in the study. She tells Carbon Brief that the paper “provides a valuable and much-needed assessment of the global hydrogen budget”. She adds:

“By better constraining the sources and sinks of hydrogen, this study helps reduce the uncertainty in the climate impact [of hydrogen].”

Dr Nicola Warwick is a researcher at the National Centre for Atmospheric Science and assistant research professor at the University of Cambridge. She tells Carbon Brief that the study “provides an important update to our understanding of the atmospheric hydrogen budget by better constraining the key sources and sinks of hydrogen”.

She adds that better understanding of hydrogen uptake by soil – including how it responds to “climate-driven changes in soil moisture and temperature” – are “essential for reliably assessing the climate impacts of any future changes in hydrogen emissions”.

Study author Jackson tells Carbon Brief that he hopes the study will “prompt people to evaluate some of these emissions and sources and sinks in new ways and new places”.

Hydrogen economy

In the pursuit of net-zero, hydrogen may play an increasingly important role in the global energy system.

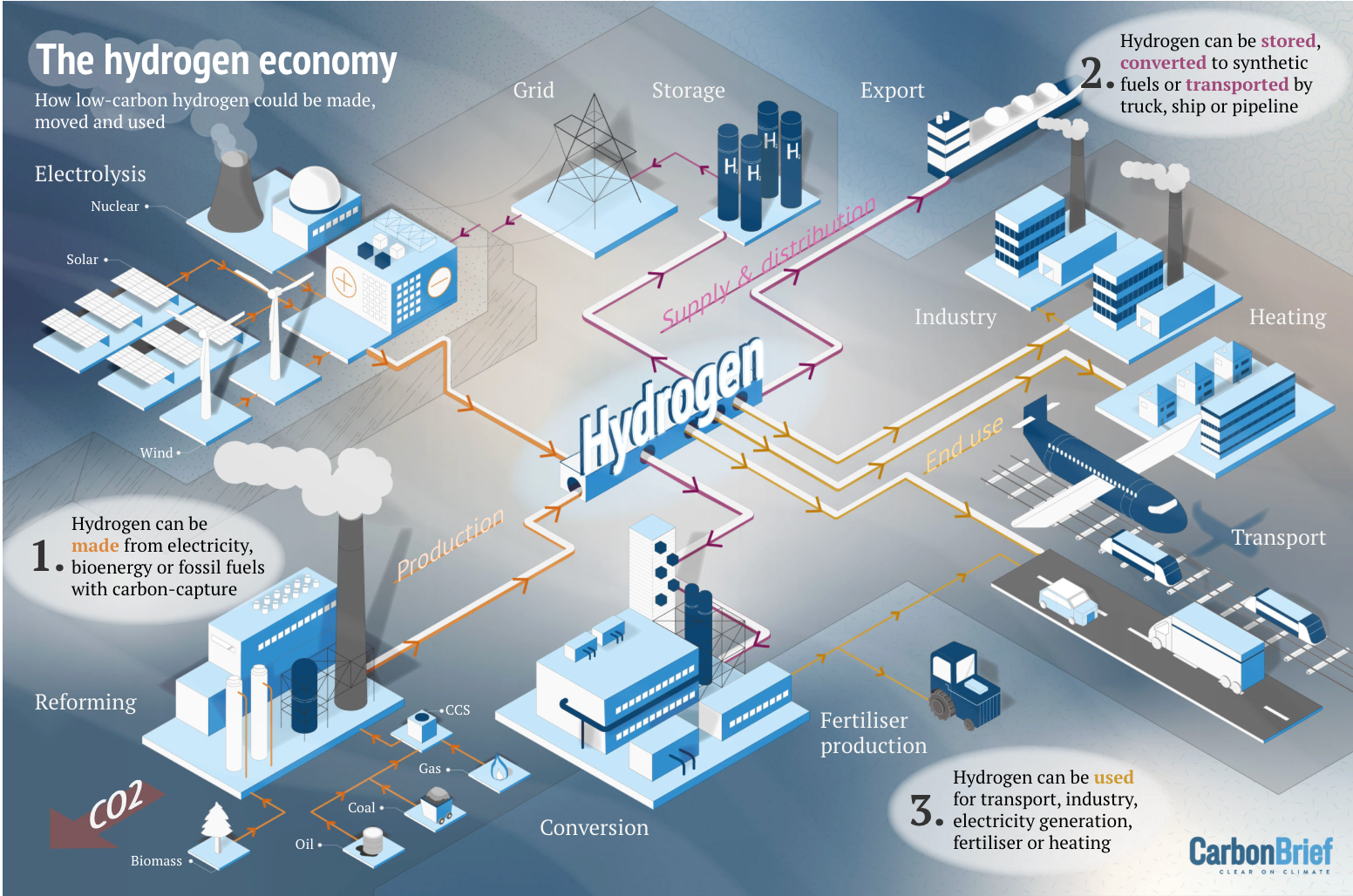

There are many ways to produce hydrogen gas. Most hydrogen is currently generated through a process called steam reforming, which brings together fossil gas and steam to produce hydrogen, with CO2 as a by-product.

According to the study, more than 90% of hydrogen produced today uses this “carbon-intensive” method.

However, electricity can be used to split water into hydrogen and oxygen atoms, in a process called electrolysis. If renewable energy is used, hydrogen can be produced and consumed with near-zero carbon emissions.

Hydrogen can be stored, liquified and transported via pipelines, trucks or ships. It can be used to make fertiliser, fuel vehicles, heat homes, generate electricity or drive heavy industry.

This potential hydrogen “economy” is shown in the graphic below. The illustrations, with numbered captions from one to three, show how hydrogen could be made, moved and used

The graphic below, from Carbon Brief’s explainer, illustrates the elements of a potential hydrogen economy.

Jackson tells Carbon Brief that, in his opinion, hydrogen is a “brilliant” choice to replace fossil fuels on-site, for industries such as steel manufacturing. However, he says he is “concerned” about “a hydrogen economy that distributes hydrogen around the world in millions of users”, because there is potential for lots of the gas to leak.

He adds:

“We know that methane leakage is bad. Hydrogen is a smaller molecule than methane. So wherever you have methane and hydrogen together, if methane leaks, hydrogen is likely to leak even more.”

The authors model hydrogen emissions under a range of future warming scenarios over the coming century.

They find that in “low-warming scenarios with high hydrogen usage”, methane emissions are low, limiting the formation of hydrogen via the oxidation of methane. In this instance, changes in atmospheric hydrogen levels depend strongly on leakage.

Meanwhile, in higher-warming scenarios, the authors find that hydrogen use is “relatively low”, but methane emissions remain “largely unmitigated”. In this instance, they find that the additional hydrogen formed through the oxidation of methane can outweigh hydrogen released through leaks.

Overall, the authors suggest that hydrogen could cause additional warming of 0.01-0.05C by the year 2100. Study author Zutao tells Carbon Brief that this additional warming was not included in the climate projections in the last assessment report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The post Hydrogen emissions are ‘supercharging’ the warming impact of methane appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Hydrogen emissions are ‘supercharging’ the warming impact of methane

Climate Change

IEA: Declining coal demand in China set to outweigh Trump’s pro-coal policies

China’s coal demand is set to drop by 2027, more than cancelling out the effects of the Trump administration’s coal-friendly policies in the US, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Global coal demand is due to grow by 0.5% year-on-year to reach record levels in 2025, according to the latest figures in the IEA’s annual market report.

Yet this will be reversed over the next couple of years, as a faster-than-expected expansion of renewables in key Asian nations and “structural declines” in Europe push coal demand down, the agency says.

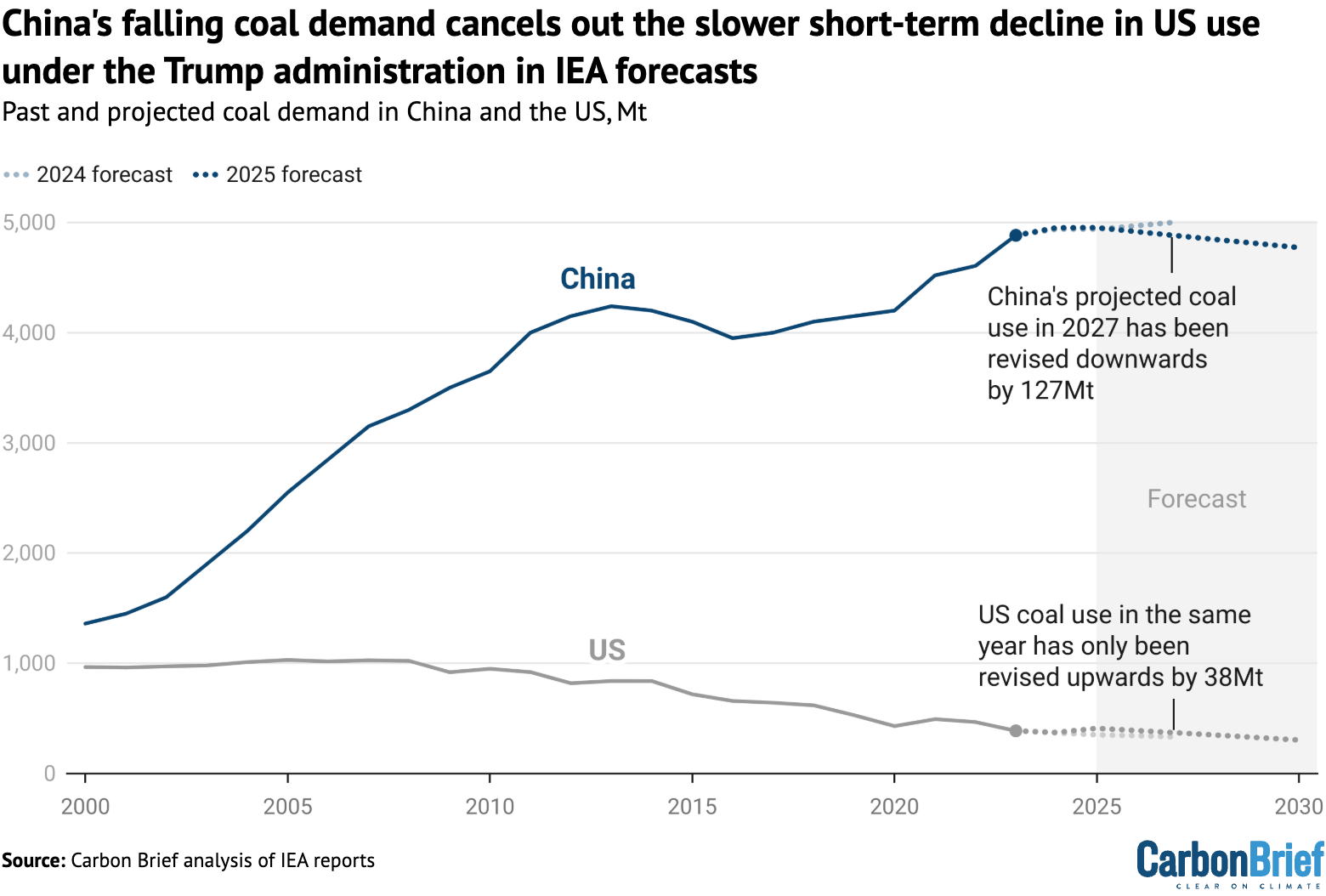

While US coal demand is set to continue falling, the decline will be slower than expected last year, due to new federal government efforts to support the fuel.

However, the IEA’s upward revision of an extra 38m tonnes (Mt) of US coal use in 2027 is dwarfed by an even larger 126Mt downward revision in China’s coal use.

‘Unusual trends’

Coal demand will reach 8,845Mt around the world in 2025. This is slightly (44Mt) higher than the IEA had forecast in its 2024 coal market report.

The agency notes some “unusual regional trends” impacting this growth, including a 37Mt year-on-year increase in US coal demand in 2025 to 516Mt. This is 59Mt (17%) higher than the IEA projected in 2024.

A new suite of measures under the Trump administration have supported the short-term use of coal, including the modernisation of existing coal plants and reopening shuttered ones.

EU coal use declined at a slower pace than expected due to lower wind and hydropower output, according to the IEA. Nevertheless, the bloc “continues its structural decline” in coal demand, driven by renewables expansion, carbon pricing and coal phaseout pledges.

India saw an unexpected dip in coal consumption in 2025, linked to a strong monsoon season that increased hydropower output and curbed electricity demand.

In China, which accounts for more than half of the world’s coal use, coal demand remained roughly unchanged between 2024 and 2025, the IEA says.

Demand drop

In its 2024 market report, the IEA projected a continued increase in global coal demand out to 2027. This was largely driven by China, which was on track to see its demand exceed 5,000Mt each year, up from 4939Mt in 2024.

In its latest forecast, the agency estimates that global coal demand will instead “plateau” in the coming years, “falling slightly by the end of the decade”.

Again, this is largely due to trends in China’s power sector, reflecting the “crowding-out” of coal from the grid by the nation’s “formidable renewables expansion” and “steady growth” of nuclear power.

(By contrast, last year clean-power sources were only expected to meet “most of” China’s rising electricity demand.)

The IEA estimates that China’s coal demand will drop to 4,879Mt by 2027 and continue falling to 4,772Mt by the end of the decade.

The global projection for 2027 is 149Mt (2%) lower than expected last year.

As the chart below shows, while US short-term coal demand is now expected to be higher than the IEA’s previous forecast, the drop in China more than makes up for this.

The projected dip in Chinese coal use is largely attributed to the “rapid expansion” of its renewable-energy capacity, the IEA notes. Renewables are soon set to provide a greater share of China’s electricity than coal, rising to 49% of generation by 2030, according to the report.

The Chinese government has set an ambition of peaking coal use before 2030.

While the IEA’s data suggests this goal will be met, the agency stresses that several factors “could turn the slight drop into a small increase”.

These include higher electricity demand, an increase in coal-to-chemicals projects and fluctuations in renewable-energy output due to weather conditions and other factors.

Meanwhile, India remains a “key driver of global coal demand”, but the new report also downgrades estimates for the nation’s future coal growth. The IEA forecasts that Indian coal demand will be 1,383Mt in 2027 – 39Mt (3%) lower than last year’s forecast.

This comes as a growing share of India’s electricity mix is provided by low-carbon power sources, with coal’s share set to decline from 70% in 2025 to 60% by 2030, according to the IEA.

The post IEA: Declining coal demand in China set to outweigh Trump’s pro-coal policies appeared first on Carbon Brief.

IEA: Declining coal demand in China set to outweigh Trump’s pro-coal policies

Climate Change

Cropped 17 December 2025: ‘Deadly’ Asia floods; Boosting London’s water birds; UN headwinds

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter. Subscribe for free here. This is the last edition of Cropped for 2025. The newsletter will return on 14 January 2026.

Key developments

UN talks face headwinds

GLOBAL OUTLOOK: A major new report calling for joint action on climate change and biodiversity was published this month at the UN Environment Assembly talks in Nairobi, Kenya, the Associated Press reported. The newswire said that more than 300 scientists from 83 countries contributed to the latest UN Environment Programme (UNEP) global environment outlook report.

‘SHARP DIVISIONS’: However, for the first time ever, countries failed to agree on a “summary for policymakers” to be published alongside the outlook, according to Agence France-Presse. It said that “sharp divisions” prevented countries reaching consensus on the high-level political summary, with “major oil producers Saudi Arabia and the US oppos[ing] references to phasing out fossil fuels”. The newswire added that UNEP chief Inger Andersen called the lack of a summary “regrettable”, but said the “integrity of the report” remained.

NEW AGREEMENTS: Separate to the report, negotiators in Nairobi were also tasked with agreeing on 15 resolutions and two decisions on a wide range of environmental topics, from plastics to the impact of artificial intelligence, forcing them to “work throughout the day and into the night” towards the end of the summit, according to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB). In the end, countries adopted 11 resolutions, including on protecting coral reefs from climate change, the global management of wildfires and the preservation of glaciers, a second ENB report said.

TURKISH INFLUENCE: Climate Home News reported that Turkey, the country co-hosting the COP31 climate summit next year alongside Australia, “sought to weaken language on climate change in several draft resolutions” being discussed at the talks. The publication said that the nation, often working alongside Saudi Arabia, “pushed to dilute wording on the climate crisis, the science of melting glaciers and the role of young and Indigenous people”. A separate Climate Home News story said that countries agreed to a first-of-its-kind resolution on addressing the environmental effects of AI, but failed to include a reference to examining its “life cycle” impacts.

‘Deadly’ Asia floods

‘NOT NORMAL’: Climate change made the rainfall behind the “deadly” floods and landslides in parts of south Asia earlier this month more likely to occur and more intense, a World Weather Attribution study covered by the Hindustan Times found. Deforestation and rapid urbanisation also contributed to the extreme flooding that killed more than 1,600 people in several countries, including Sri Lanka, Malaysia and Thailand, the newspaper said. The Guardian noted that while monsoon rains often bring flooding, scientists said this level of intensity was “not normal”.

FOREST LOSS: Mongabay looked at how deforestation contributed to the “catastrophic” impacts from Cyclone Senyar, which caused floods and landslides in Sumatra, Indonesia. The outlet said that “decades of deforestation, mining, plantations and peat drainage left watersheds unable to absorb intense rainfall”. Indonesian environmental group WALHI told the Associated Press that deforestation “stripped away natural defences that once absorbed rainfall and stabilised soil”. Gus Irawan Pasaribu, a local government leader in Tapanuli, told Reuters: “If our forests were well-preserved…it would not have been this terrible.”

NATURE IMPACTS: A separate Mongabay article reported on the “extensive” damage caused by Cyclone Ditwah to Sri Lanka’s “biodiversity-rich” central highlands earlier this month. The outlet said that initial assessments have shown disastrous impacts of flooding and landslides in places such as the Knuckles mountain range, a “Unesco-listed biodiversity hotspot”. Meanwhile, the floods that hit Indonesia were an “extinction-level disturbance” for the Tapanuli orangutan – the world’s rarest great ape, scientists told the Guardian.

Spotlight

Building a bird sanctuary at a London reservoir

In this Spotlight, Carbon Brief visits a radical conservation project aiming to reverse a decline in water birds at a Victorian reservoir in north London.

“I’d recommend bringing wellies! It’s very muddy.”

Those were the instructions of Ben MacMillan, an ecologist at the Canal & River Trust, a charity responsible for looking after the UK’s waterways, including canals, reservoirs and towpaths.

On a damp and grey Tuesday morning, he guided Carbon Brief round the back of a playing fields car park in Hendon, north London, past a metal fence reading “no entry” and across ground covered by several inches of mud to the unlikely site of a radical new conservation effort.

The site is at a degraded wetlands on the northern edge of the Welsh Harp reservoir, a large human-made lake capable of holding 400 Olympic-sized swimming pools of water, first established by the Victorians in the 1830s.

In the 1950s, the reservoir was declared one of the UK’s “sites of special scientific interest”, due to its ability to host an unusually large number of species, including breeding waterbirds, such as silvery-grey common terns and elegant great-crested grebes.

Despite the designation, little was done to protect the site from various threats, including the spread of invasive species, increasing urbanisation and pollution from major roads. The reservoir is bordered on one side by the M1, the main motorway from London to northern England, and by the North Circular, part of central London’s busy ring-road, on another.

In the 1980s, a conservation project led by ecologist Leo Batten transformed the site to create new refuges for breeding birds.

However, for the past 40 years, the reservoir has fallen into “mismanagement”, according to MacMillan – with devastating consequences for its wildlife.

In 2022, just two tern chicks were successfully fledged at the reservoir, compared to 44 in 2000, MacMillan said. Great-crested grebe nests have also dropped from 55 in 1987 to 27 in 2022.

Redesigning the landscape

The dramatic decline has spurred the start of a new £400m restoration project, called “wings on water”, which began in October 2025 and will continue for the next three years.

Headed by MacMillan, the project is making radical changes to the landscape of the site in order to create new habitats and breeding spots for its water birds.

MacMillan has contracted the services of restoration specialists Ebsford Environmental, who have used diggers to create a network of channels across the site.

These channels have uncovered a series of islands that can offer birds a safe place to breed, away from predators such as urban foxes and mink, MacMillan said.

As well as dredging the landscape, MacMillan also plans to introduce new micro-ecosystems, such as wildflower meadows, that will eventually form a “patchwork” capable of supporting a wide range of species.

“It’s all about creating a diversity of habitat,” he said. “It might take five or 10 years to develop, but eventually we’ll end up with an amazing complex mosaic of habitats.”

While MacMillan is “very happy” with the progress being made, the project has some issues to contend with.

One of the recently dug channels is contaminated by toxic silt, poisoned by the runoff of petrol from the nearby major roads. If the petrol seeps out of the silt, it could coat the feathers of birds, negatively affecting their health, MacMillan said.

Ninja turtle legacy

The site is also home to a number of invasive species, each with their own impacts.

One animal causing a particular nuisance are red-eared terrapins, a type of omnivorous shelled reptile, similar in appearance to a turtle, that are native to the US.

“They link back to the 1990s Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtle craze,” MacMillan explained. “People bought loads of them. Then they thought: ‘Oh, these are getting a bit big now’ – and decided to release them in their local park.”

Terrapins have a life span of around 40 years, meaning many released on a whim 30 years ago have now established themselves in waterway habitats across the UK.

While terrapins feed on plants, they have also been seen taking chicks and eggs from nesting birds, MacMillan said:

“In an ideal world, we would move them on. But in practice, it’s very difficult to actually catch them.”

As well as restoring the site for the good of birds, the project also aims to improve access to nature for the local community.

The team plans to install a new boardwalk and viewing platform for the public, which they aim to open next year.

“It should provide a really nice space for people to take a walk in a green space, while being able to spot some breeding birds, in a very urbanised area,” MacMillan said.

News and views

NATURE CASH: The ‘Cali Fund’ – which could generate billions of dollars each year for conservation – recently received its first donation of just $1,000, Carbon Brief reported. On 19 November, nine months after the fund launched, UK start-up TierraViva AI put forward the contribution. The company’s chief executive told Carbon Brief that this was an “ice-breaker” aimed to encourage others to pay in. One expert described the contribution as a good “first step”, but said it is now “time for larger actors to step forward”. Large companies in sectors such as pharmaceutical, cosmetic, biotechnology, agribusiness and technology could contribute to the fund.

FARMING LOSSES: UK crop farmers lost more than £800m in 2025 due to poor harvests and “record heat and drought”, the Guardian reported, based on analysis from the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU). Farmers recorded one of the worst harvests on record this year, with production of wheat, oats, spring and winter barley and oilseed rape dropping 20% below the 10-year average. Three of the five worst harvests have occurred since 2020, the newspaper added, quoting the ECIU’s Tom Lancaster: “The evidence suggests that climate impacts are what’s actually driving issues of profitability.” Meanwhile, BBC News reported that the UK government “roll[ed] back” certain nature protection requirements for housing developers in England.

CLIMATE FINANCE: Biodiversity, conservation and anti-desertification programmes in Africa have struggled to fill a “funding vacuum” since the US froze its development aid earlier this year, according to Mongabay. Experts and observers told the outlet they are “increasingly concerned” about the funding gap that “neither Europe nor billionaire philanthropists seem ready to fill”. Amhed Moustapha Mfokeu, a Cameroonian expert in climate finance, told Mongabay that the closure of the US Agency for International Development (USAID) “created a significant gap in funding for climate-related projects”.

SAVING SOILS: Around 70% of countries do not prioritise soil restoration in their national climate plans, a new report covered by EFEVerde found. The report, from the International Union for the Conservation of Nature’s world commission on environmental law and other groups, said that healthier soils can absorb more carbon and help to limit global warming, the outlet noted. Praveena Sridhar from the Save Soil movement wrote in Earth.org that the recent COP30 climate talks in Brazil “regarded [soils] as a sub-component of the agricultural machine, instead of the foundation to agriculture and many other components of terrestrial life”.

TRADE DEAL: The European parliament voted in favour of including measures to “protect European farmers” in a potential trade deal with South American countries, Bloomberg reported. The outlet said the EU is “rushing” this week to finalise the Mercosur deal, which has been negotiated over the past 25 years and aims to boost trade between the EU and Argentina, Brazil, Uruguay and Paraguay. Reuters reported that France and Italy want to delay the vote, with France trying to “form a blocking minority” against the agreement.

XMAS CHEER: Christmas tree farmers in Canada are adapting to climate change impacts such as warmer weather, CBC News reported. Michael Cormack, who owns a tree farm near Toronto, told the outlet: “This year in July, we were averaging over 29C. So we had trees from two to three years ago that just died…Four years ago, we had a tornado here that wiped out a bunch of our stuff.” The outlet also addressed the age-old question of whether a real or artificial christmas tree is more “eco-friendly”, with one tree researcher saying that a real tree bought from a “local farmer” tends to be a lower-emission choice, or re-using an artificial tree for a long time.

Watch, read, listen

KOLAHOI GLACIER: A retreating glacier in Kashmir is “transforming landscapes and communities”, the Guardian said.

FISHY: DeSmog investigated accusations that the world’s largest salmon producer has wielded a “charm offensive” in the Scottish Highlands to distract from its “noisy” and “polluting” fish farms.

LIVING UNDER THREAT: The Associated Press reported on the “steep risks” environmental activists face in Colombia – the “deadliest country in the world” for environmental defenders.

BAMBOO BARRIER: Rivercane – a species of bamboo – could help protect the southern US from future floods, Grist reported.

New science

- Hard coral cover in Caribbean reefs has reduced by almost half since 1980 | Global Coral Reef Monitoring Network and International Coral Reef Initiative

- Three decades of Amazon forest data shows “higher tree mortality during intense droughts” | Nature

- Vertebrate species could face unsuitable conditions across 10-52% of their range by 2100 due to climate and land-use changes | Global Change Biology

In the diary

- 15-19 December: 70th meeting of the Global Environment Facility council | Virtual

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz. Ayesha Tandon also contributed to this issue. Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 17 December 2025: ‘Deadly’ Asia floods; Boosting London’s water birds; UN headwinds appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Cropped 17 December 2025: ‘Deadly’ Asia floods; Boosting London’s water birds; UN headwinds

-

Climate Change4 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases4 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Why airlines are perfect targets for anti-greenwashing legal action