China’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions stayed at, or just below, last year’s levels in the third quarter of 2024, after a fall in the second quarter.

The new analysis for Carbon Brief, based on official figures and commercial data, leaves open the possibility that China’s emissions could fall this year.

However, recent record-high temperatures caused emissions to go up in September and new government stimulus measures mean there is now greater uncertainty over the country’s emissions trajectory.

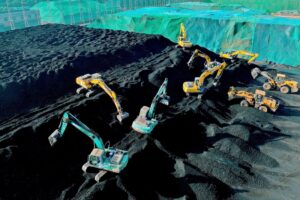

Heatwaves through much of August and September caused a major increase in electricity demand for air conditioning, which, combined with weak hydropower output, meant a 2% increase in coal-fired power generation and a 13% rise for gas-fired power in the third quarter, despite wind and solar growth continuing to break records.

The increase in emissions in the power sector was offset by falling emissions from steel, cement and oil use, plus stagnating gas demand outside the power sector, meaning China’s CO2 output in the third quarter was flat or slightly declined, relative to a year earlier.

Other key findings from the analysis include:

- Solar generation rose 44% in the third quarter of the year and wind by 24%, with both continuing to see record-breaking additions of new capacity.

- Hydro generation was up 11% compared with last year’s drought-affected figures, but remained short of expected output. Nuclear power was up 4%.

- Oil demand fell by around 2%, due to falling construction activity, the rise of electric vehicles (EVs) and natural gas (LNG) trucks, as well as weak consumer spending.

- Emissions from steel fell by 3% and cement by 12% in the third quarter, as both sectors continued to see the effect of falling construction activity.

- The coal-to-chemicals industry received renewed political backing and coal consumption in the sector has risen by nearly a fifth in the year to date.

Emissions would need to fall by at least 2% in the last three months of the year, for China’s annual total to drop from 2023 levels. This outcome is supported by the ongoing slowdown in industrial power demand growth and the end of the air-conditioning season.

However, new economic stimulus plans announced in late September with no apparent emphasis on emissions, add uncertainty to this outlook.

In any case, China will remain off track against its 2025 “carbon intensity” target, which requires emissions cuts of at least 2% in 2024 and 2025, after rapid rises in 2020-23.

Looking further ahead, policymakers recently provided new indications of the country’s plans for peaking and reducing emissions, signalling a gradual and cautious approach which falls short of what would be needed to align with the goals of the Paris Agreement.

But, if the country’s rapid clean energy growth is sustained, it has the potential to deliver emission reductions more swiftly.

Clean-energy expansion met all power-demand growth over summer

Defying predictions of slowing growth, China’s electricity demand increased by 7.2% year-on-year in the third quarter of 2024, up from an already rapid 6.9% in the second quarter.

The make-up of growth changed, however. Some 60% of the increase in demand came from the residential and services sectors, with household demand up by a blistering 15%.

Industrial power-demand growth continued to slow down, increasing by 4.6% in July–September, down from 5.9% in the second quarter.

At the same time, solar power generation increased by 44% year-on-year and wind power generation by 24%. Hydropower grew 11%, despite falling short of average utilisation, and nuclear power generation growth was muted at 4% due to few new reactors being commissioned.

The rapid rise of electricity demand outpaced these increases from low-carbon sources, with the gap between demand and rising clean supply being met by a 2% increase in coal-fired power generation and a 13% rise for gas-fired power, as shown in the figure below.

This caused a 3% increase in CO2 emissions from the sector in the third quarter of the year.

However, looking at the whole summer period, whether taken as May-September or June-August, clean-energy expansion covered all of electricity demand growth.

This year, August and September were hotter than last year, resulting in rapid growth in power demand for air conditioning. Last year, in contrast, June and July were hotter.

Thermal power generation from coal and gas fell overall during the summer period, despite the rapid increase in residential power demand, with a 7% drop in June, 5% drop in July, a 4% increase in August and a 9% increase in September. Growth rates during individual months are heavily affected by which months the worst heatwaves fall on.

In terms of newly built generating capacity, solar continued to break last year’s records, with 163 gigawatts (GW) added in the first nine months of 2024. This is equal to the combined total capacity in Germany, Spain, Italy and France, the four EU countries with the most solar capacity. China’s solar capacity additions in the third quarter were up 22% year-on-year, as shown in the figure below.

The growth in China’s solar power output this year alone is likely to equal the total power generation of Australia or Vietnam in 2023, based on growth rates during the first nine months of the year.

Wind power additions accelerated as well, with 38GW added in the year to September, up 10% year-on-year and exceeding the total wind power capacity in the UK of 30GW.

China’s State Council approved 11 new nuclear reactors for construction in one go in August. The total power generating capacity of the approved projects is about 13GW. With 10 reactors approved in both 2022 and 2023 – and now 11 in 2024 – the next batch of nuclear power capacity is getting off the ground and adding to China’s clean-energy growth.

Hydropower capacity only increased 2% year-on-year, implying that most of the 11% third-quarter increase in generation was due to a recovery in capacity utilisation.

In response to severe droughts, utilisation had fallen to its lowest level in more than a decade in 2022, and recovered only partially in 2023, so this year’s recovery was expected and is closer to expected average hydropower generation.

China’s approvals of new coal power plant projects plummeted by 80% in the first half of 2024. Just 9GW of new capacity was approved, down from 52GW in the first half of last year. However, according to the Polaris Network, an energy sector news and data provider, eight large coal power projects were approved in the third quarter, likely representing an uptick in the rate of approvals compared with the first half of the year.

Construction and oil demand slowdown continued to pull down total emissions

While power sector emissions saw a small amount of growth in the third quarter of 2024, the ongoing contraction in construction volumes pulled down total emissions.

As a result, CO2 emissions stayed flat in the third quarter of 2024, at or just below the levels seen in the same period a year earlier, as shown in the figure below.

Digging deeper into the construction-led decline in emissions outside the power sector, steel output fell 9% and cement 12%, as real estate investment contracted 10% in the third quarter, maintaining the same rate as in the first half-year.

This translated into an 11% (24m tonnes of CO2, MtCO2) reduction in CO2 emissions from cement compared with the same period in 2023, shown in the figure below.

Steel emissions only fell by 3% (13MtCO2), despite the 9% fall in steel production. The reason is that the brunt of the drop in demand was borne by electric arc steelmakers rather than the coal-based steel plants with a much higher emission intensity.

The sector lacks the incentive to prioritise electric arc furnaces, which use recycled scrap and have much lower emissions. In theory, this could be encouraged by the inclusion of steel in China’s emissions trading system.

However, if the sector is treated in the same way as power, with separate benchmarks for coal-based and electric steelmaking, it will not create incentives to switch to electricity.

As one step towards structural change in the sector, the industry ministry issued a policy suspending all permitting of new steelmaking capacity, turning a de-facto stop to new permits – observed since the beginning of the year – into a formal moratorium. Until last year, the sector had been investing heavily in new coal-based steel capacity.

The other major area where emissions fell is oil consumption, which saw a 2% (13MtCO2) reduction in oil-related CO2 emissions in the third quarter of the year, also shown in the figure above. This is based on numbers from the National Bureau of Statistics.

The reduction in oil demand and related CO2 emissions may have been even steeper. The supply of oil products, measured as refinery throughput net of imports and exports, fell much more sharply. Based on this measure, CO2 from burning oil fell 10% (63MtCO2) in the third quarter, meaning that China’s CO2 emissions overall would have fallen by 2%.

The much more modest drop reported by the statistics agency could reflect the tendency of China’s statistical reporting to smooth downturns and upticks.

Another possible explanation is that refineries had previously been producing more than was being consumed, and have now had to cut output to reduce inventories.

Regardless of the magnitude of the drop, it is possible to identify the drivers of falling oil consumption. The fall in construction volumes is a major factor, as a significant share of diesel is used at construction sites and for transporting building materials.

The increase in the share of EVs is eating into petrol demand. Demand was also driven down by household spending, which remained weak until picking up in October in response to expectations of government stimulus.

The increasing share of trucks running on LNG also contributed to the fall in diesel demand. LNG truck sales accounted for about 20% of total truck sales in the nine months to March 2024, but weak overall gas demand growth indicates that this had a limited impact.

Gas consumption growth slowed down to 3% in the third quarter, from 10% in the first half of the year. Growth took place entirely in the power sector, with demand from other sectors stagnating, likely due to weak industrial demand.

After an increase in emissions in January-February, falling emissions in March-August and an increase in September, emissions would need to fall by at least 2% in the last three months of the year, for China’s annual total to drop from 2023 levels.

There is a good chance this will happen, due to an ongoing slowdown in industrial power demand growth and the end of the air conditioning season. But, even then, China would remain off track against its 2025 carbon intensity target, which requires emissions to fall by at least 2% in both 2024 and 2025, after rapid increases from 2020 to 2023.

The fundamental reason why emissions have not fallen faster – and may not have fallen at all in the third quarter – is that energy consumption growth this year continues to be much faster than historical trends.

Total energy consumption – including, but not limited to electricity consumption – grew 5.0% in the third quarter, faster than GDP, which gained 4.6%.

Until the Covid-19 pandemic, China’s energy demand growth had been much slower than GDP growth, implying falling energy intensity of the economy.

The post-Covid economic policy focused on manufacturing appears to have reversed this trend.

Coal-to-chemicals industry received new political backing

One additional wildcard in the outlook for China’s CO2 emissions is the coal-to-chemicals industry. The sector turns domestic coal into replacements for imported oil and gas, albeit with a far higher carbon footprint.

A recent policy from the National Development and Reform Commission, China’s powerful planning agency, called for ”accelerating” the development of the coal-to-chemical industry, including “speeding up the construction of strategic bases for coal-to-oil and coal-to-gas production”.

The past weeks after the issuance of the new policy have seen construction starts of a major coal-to-oil project in Shanxi, a coal-to-chemicals park in Sha’anxi and approval of a similar project in Xinjiang.

The coal-to-chemicals industry is expected to use more than 7% of all coal consumed in China in 2024, according to China Futures Research, a consultancy.

Coal consumption by the chemicals industry increased 18% in the first eight months of 2024, after a 9% increase in 2023, based on data from Wind Financial Terminal. This increase in coal consumption for coal-to-chemicals contributed two thirds of the 0.9% increase in total fossil CO2 emissions during the January to August period.

Coal consumption growth in the sector slowed down to 5% in July-August, however, and output of chemical products continued to slow in September. This smaller contribution to growth in CO2 emissions is shown in the graph above (“chemical industry”).

The recent rise in oil and gas prices, together with efforts to increase China’s domestic coal production and drive down domestic coal prices, have provided a major boost to the coal chemicals sector, which has a high sensitivity to both oil and coal prices.

Coal-to-chemicals is the sector where China’s policy priorities of energy security and emission reductions are most directly at odds.

Economic stimulus adds uncertainty to emissions outlook

After economic data indicated continuing slowdown and shortfall against GDP growth targets over the summer, expectations of a stimulus package built up.

The government responded in late September with a set of announcements, pledging various stimulus measures. The measures were focused on financial markets, but also included a commitment to “stabilise” the housing market.

The size of the stimulus package is not very large by China’s standards, and further details have disappointed those who hoped for a more radical policy turnaround. Yet, the package is clearly thought-through and coordinated, offering insights into how China’s top policymakers are planning to address the economic headwinds.

Direct income transfers of government money to households, which have been a hot topic for the past couple of years, are now going to be tried out.

Efforts to boost household spending, instead of the energy-intensive manufacturing and construction that has been the focus of previous rounds of government stimulus, would enable China to grow in a much less energy- and carbon-intensive way.

However, the sums allocated to income transfers are very small in relation to the size of the whole package. Much more money will be spent on subsidies to car and white-goods purchases. This will free up household cash for other types of spending, but it also directs household spending in the most energy-intensive direction.

Most of the stimulus is directed through the traditional routes of local government borrowing and bank lending, which tend to go into industrial and infrastructure projects.

There is no explicit climate-related emphasis to this stimulus. Quite a bit of it is likely to flow to clean energy-related investments, simply because those have been so dominant in China’s investment flows recently, but there is no further push in that direction.

Policymakers do not see an ‘early’ peak

While the rapid clean-energy growth points to the possibility of China’s emissions peaking imminently, policymakers are still setting an expectation that emissions will increase until the end of the decade and plateau or fall very gradually thereafter.

In August, China’s National Energy Administration played down the possibility of the country’s emissions having already peaked, in response to a question from a reporter referencing analyses suggesting this was possible.

The NEA department head who responded to the question emphasised that the timeline for peaking the country’s emissions – “before 2030” – has already been set by the top leadership, implying that the NEA has no mandate to change it.

The Central Committee of the Communist Party – one of the country’s highest leadership groups – reaffirmed that the aim is to “establish a falling trend” in emissions by 2035.

An earlier State Council plan said that China would focus on controlling total CO2 emissions, rather than emissions intensity, after the emission peak has been reached, and indicated that this would not happen in the 2026-30 period.

A very gradual approach to peaking emissions and reducing them after the peak, leaving more substantial emission reductions to later decades, is permissible under China’s current commitments under the Paris Agreement.

However, such a pathway would see the country use up 90% of the global emission budget for 1.5C. In scenarios that limit warming to 1.5C, China’s emissions are cut to at least 30% below 2023 levels by 2035. And recent International Energy Agency (IEA) analysis found that emerging markets such as China would need to cut emissions to 35-65% below 2022 levels by 2035, to align with the global pledges made at COP28 or national net-zero targets.

In contrast with the cautious approach telegraphed by Chinese policymakers, maintaining the rate of clean energy additions and electrification achieved in recent years could deliver a 30% reduction in CO2 emissions from fossil fuels by 2035, relative to 2023 levels.

Similarly, the IEA’s latest World Energy Outlook found clean-energy growth would help cut China’s CO2 emissions to 24% below 2023 levels by 2035, based on current policy settings. This reduction would increase to 45% by 2035 if China met its announced ambitions and targets, the IEA said.

China’s upcoming nationally determined contribution (NDC), due to be submitted to the UN under the Paris Agreement by February 2025, is expected to provide more clarity on which emissions pathway the policymakers are pursuing.

About the data

Data for the analysis was compiled from the National Bureau of Statistics of China, National Energy Administration of China, China Electricity Council and China Customs official data releases, and from WIND Information, an industry data provider.

Wind and solar output, and thermal power breakdown by fuel, was calculated by multiplying power generating capacity at the end of each month by monthly utilisation, using data reported by China Electricity Council through Wind Financial Terminal.

Total generation from thermal power and generation from hydropower and nuclear power was taken from National Bureau of Statistics monthly releases.

Monthly utilisation data was not available for biomass, so the annual average of 52% for 2023 was applied. Power sector coal consumption was estimated based on power generation from coal and the average heat rate of coal-fired power plants during each month, to avoid the issue with official coal consumption numbers affecting recent data.

When data was available from multiple sources, different sources were cross-referenced and official sources used when possible, adjusting total consumption to match the consumption growth and changes in the energy mix reported by the National Bureau of Statistics for the first quarter, the first half and the first three quarters of the year. The effect of the adjustments is less than 1% for total emissions, with unadjusted numbers showing a 1% reduction in emissions in the third quarter.

CO2 emissions estimates are based on National Bureau of Statistics default calorific values of fuels and emissions factors from China’s latest national greenhouse gas emissions inventory, for the year 2018. Cement CO2 emissions factor is based on annual estimates up to 2023.

For oil consumption, apparent consumption is calculated from refinery throughput, with net exports of oil products subtracted.

The post Analysis: No growth for China’s emissions in Q3 2024 despite coal-power rebound appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: No growth for China’s emissions in Q3 2024 despite coal-power rebound

Climate Change

Experts: The key ‘unknowns’ of overshooting the 1.5C global-warming limit

Last week, around 180 scientists, researchers and legal experts gathered in Laxenburg, Austria to attend the first-ever international conference focused on the controversial topic of climate “overshoot”.

This hypothesised scenario would see global temperatures initially “overshoot” the Paris Agreement’s aspirational limit of 1.5C, before they are brought back down through techniques that would remove carbon dioxide from the atmosphere.

(For more on the key talking points, new research and discussions that emerged from the three-day conference, see Carbon Brief’s full write-up of the event.)

On the sidelines of the conference, Carbon Brief asked a range of delegates what they consider to be the key “unknowns” around overshoot.

Below are their responses, first as sample quotes, then, in full:

- Dr James Fletcher: “Yes, there will be overshoot, but at what point will that overshoot peak? Are we peaking at 1.6C, 1.7C, 2.1C?”

- Prof Shobha Maharaj: “There are lots of places in the world where adaptation plans have been made to a 1.5C ceiling. The fact is that these plans are going to need to be modified or probably redeveloped.”

- Sir Prof Jim Skea: “There are huge knowledge gaps around overshoot and carbon dioxide removal.”

- Prof Kristie Ebi: “If there is going to be a peak – and, of course, we don’t know what that peak is – then how do you start planning?”

- Prof Lavanya Rajamani: “To me, a key governance unknown is the extent to which our current legal and regulatory architecture…will actually be responsive to the needs of an overshoot world.”

- Prof Nebojsa Nakicenovic: “One of my major concerns has been for a long time…is whether, even after reaching net-zero, negative emissions can actually produce a temperature decline.”

- Prof Debra Roberts: “For me, the big unknown is how all of these areas of increased impact and risk actually intersect with one another and what that means in the real world.”

- Prof Oliver Geden: “[A key unknown] is whether countries are really willing to commit to net-negative trajectories.”

- Dr Carl-Friedrich Schleussner: “This is a bigger concern that I have – that we are pushing the habitability in our societies on this planet above that limit and towards maybe existential limits.”

- Dr Anna Pirani: “I think that tracking global mean surface temperature on an overshoot pathway will be an important unknown.”

- Prof Richard Betts: “One of the key unknowns is are we going to continue to get the land carbon sink that the models produce.”

- Prof Hannah Daly: “The biggest unknown is whether countries can translate these global [overshoot] pathways into sustained domestic action…that is politically and socially feasible.”

- Dr Andrew King: “[W]e still have a lot of uncertainty around other elements in the climate system that relate more to what people actually live through.”

Former minister for public service, sustainable development, energy, science and technology for Saint Lucia and negotiator at COP21 in Paris.

The key unknown is where we’re going to land. At what point will we peak [temperatures] before we start going down, and how long will we stay in that overshoot period? That is a scary thing. Yes, there will be overshoot, but at what point will that overshoot peak? Are we peaking at 1.6C, 1.7C, 2.1C? All of these are scary scenarios for small island developing states – anything above 1.5C is scary. Every fraction of a degree matters to us. Where we peak is very important and how long we stay in this overshoot period is equally important. That’s when you start getting into very serious, irreversible impacts and tipping points.

Adjunct professor at the University of Fiji and a coordinating lead author for Working Group II of the IPCC’s seventh assessment

First of all, there is an assumption that we’re going to go back down from overshoot. Back down is not a given. And secondly, we are still in the phase where we are talking about uncertainty. Climate scientists don’t like uncertainty. We are not acknowledging that uncertainty is the new normal… But because we’re so bogged down in terms of uncertainties, we are not moving towards [the issue of] what we do about it. We know it’s coming. We know the temperatures are going to be high. But there is little talk about the action.

The focus seems to be more on how we can understand this or how we can model this, but not what we do on the ground. Especially when it comes to adaptation planning – [and around] how does this modify whatever the plans are? There are lots of places in the world where adaptation plans have been made to a 1.5C ceiling. The fact is that these plans are going to need to be modified or probably redeveloped. And no one is talking about this, especially in the areas that are least resourced in the world – which sets up a big, big problem.

Chair of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and emeritus professor at Imperial College London’s Centre for Environmental Policy

There are huge knowledge gaps around overshoot and carbon dioxide removal. As it’s very clear from the themes of this conference, we don’t altogether understand how the Earth would react in taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. We don’t understand the nature of the irreversibilities and we don’t understand the effectiveness of CDR techniques, which might themselves be influenced by the level of global warming, plus all the equity and sustainability issues surrounding using CDR techniques.

Professor of global health at the University of Washington‘s Center for Health and the Global Environment

There are all kinds of questions about adaptation and how to approach effective adaptation. At the moment, adaptation is primarily assuming a continual increase in global mean surface temperature. If there is going to be a peak – and of course, we don’t know what that peak is – then how do you start planning? Do you change your planning? There are places, for instance when thinking about hard infrastructure, [where overshoot] may result in a change in your plan – because as you come down the backside, maybe the need would be less. For example, when building a bridge taller. And when implementing early warning systems, how do you take into account that there will be a peak and ultimately a decline? There is almost no work in that. I would say that’s one of the critical unknowns.

Professor of international environmental law at the University of Oxford

I think there are several scientific unknowns, but I would like to focus on the governance unknowns with respect to overshoot. To me, a key governance unknown is the extent to which our current legal and regulatory architecture – across levels of governance, so domestic, regional and international – will actually be responsive to the needs of an overshoot world and the consequences of actually not having regulatory and governance architectures in place to address overshoot.

Distinguished emeritus research scholar at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis and executive director of The World In 2050.

One of my major concerns has been for a long time – as it was clear that we are heading for an overshoot, as we are not reducing the emissions in time – is whether, even after reaching net-zero, negative emissions can actually produce a temperature decline…In other words, there might be asymmetry on the way down [in the global-temperature response to carbon removal] – it might not be symmetrical to the way up [as temperature rise in response to carbon emissions]. And this is really my major concern, that we are planning measures that are so uncertain that we don’t know whether they will reach the goal.

The last point I want to make is that I think that the scientific community should, under all conditions, make sure that the highest priority is on mitigation.

Honorary professor at the University of KwaZulu-Natal, coordinating lead author on the IPCC’s forthcoming special report on climate change and cities, board chair of the Red Cross Red Crescent Climate Centre and co-chair of Working Group II for the IPCC’s sixth assessment

Well, I think coming from the policy and practitioner community, what I’m hearing a lot about are the potential impacts that come from the exceedance component of overshoot. What I’m not hearing a lot about is the responses to overshoot and their impacts – and how those impacts might interact with the impacts from temperature exceedance. So there’s quite a complex risk landscape emerging. It’s three dimensional in many ways, but we’re only talking about one dimension and, for policymakers, we need to understand that three dimensional element in order to understand what options remain on the table. For me, the big unknown is how all of these areas of increased impact and risk actually intersect with one another and what that means in the real world.

Senior fellow and head of the climate policy and politics research cluster at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs and vice-chair of IPCC Working Group III

[A key unknown] is whether countries are really willing to commit to net-negative trajectories. We are assuming, in science, global pathways going net negative, with hardly any country saying they want to go there. So maybe it is just an academic thought experiment. So we don’t know yet if [overshoot] is even relevant. It is relevant in the sense that if we do, [the] 1.5C [target] stays on the table. But I think the next phase needs to be that countries – or the UNFCCC as a whole – needs to decide what they want to do.

Research group leader and senior research scholar at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis

I’m convinced that there’s an upper limit of overshoot that we can afford – and it might be not far outside the Paris range [1.5C-2C] – before human societies will be overwhelmed with the task of bringing temperatures back down again. This [societal limit] is lower than the geophysical limits or the CDR limit.

The impacts of climate change and the challenges that will come with it will undermine society’s abilities to cooperatively engage in what is required to achieve long-term temperature reversal. This is a bigger concern that I have – that we are pushing the habitability in our societies on this planet above that limit and towards maybe existential limits. We may not be able to walk back from it, even if we wanted to. That is a big unknown to me.

I’m convinced that there is an upper limit to how much overshoot we can afford, and it might be just about 2C or a bit above – it might not be much more than that. But we do not have good evidence for this. But I think these scenarios of going to 3C and then assuming we can go back down – I have doubts that future societies grappling with the impacts of climate change will be in the position to embark on such an endeavour.

Senior research associate at the Euro-Mediterranean Center on Climate Change (CMCC) and former head of the Technical Support Unit for Working Group I of the IPCC

I think that tracking global mean surface temperature on an overshoot pathway will be an important unknown – how to take account of natural variability in that context, to inform where we are on an overshoot pathway and how well we’re doing on it. I think, methodologically, that would prove to be a challenge. The fact that it occurs over many, many years – many decades – and, yet, we sort of think about it as a nice curve. We see these graphs that say “by the 2050s, we will be here and we’ll start declining and so on”. I think that what that actually translates to in the evolution of global surface temperatures is going to be very difficult to measure and track. Even how we report on that, internationally, in the UNFCCC [UN Framework Convention on Climate Change] context and what the WMO [World Meteorological Organization] does in terms of reporting an overshoot trajectory, that would be quite a challenge.

Head of climate impacts research in the Met Office Hadley Centre and professor at the University of Exeter

One of the key unknowns is are we going to continue to get the land carbon sink that the models produce. We have got model simulations of returning from an overshoot.

If you are lowering temperatures, you have got to reduce emissions. The amount you reduce emissions depends on how much carbon is taken up naturally by the system – by forests, oceans and so on. The models will do this; they give you an answer. But we don’t know whether they are doing the right thing. They have never been tested in this kind of situation.

In my field of expertise, one of the key [unknowns] is how these carbon sinks are going to behave in the future. That is why we are trying to get real-world data into the models – including through the Amazon FACE project – so we can really try and narrow the uncertainties in future carbon sinks. If the carbon sinks are weaker than the models think, it is going to be even harder to reduce emissions and we will need to remove even more by carbon capture and removal.

Professor of sustainable energy at University College Cork

We know ever more about the profound – and often irreversible – damages that will be felt as we overshoot 1.5C. Yet we seem no closer to understanding what will unlock the urgent decarbonisation that remains our only way to avoid the worst impacts of climate change.

Global models can show, on paper, what returning temperatures to safer levels after overshoot might look like. The biggest unknown is whether countries can translate these global pathways into sustained domestic action – over decades and without precedent in history – that is politically and socially feasible.

Associate professor in climate science at the University of Melbourne

I think, firstly, can we actually achieve net-negative emissions to bring temperatures down past a peak? It’s a completely different world and, unfortunately, it’s likely to be challenging and we’re setting ourselves up to need to do it more. So I think that’s a huge unknown.

But then, beyond that, I think also, whilst we’ve built some understanding of how global temperature would respond to net-zero or net-negative emissions, we still have a lot of uncertainty around other elements in the climate system that relate more to what people actually live through. In our warming world, we’ve seen that global warming relates to local warming being experienced by everyone at different amounts. But, in an overshoot climate, we would see quite diverse changes for different people, different areas of the world, experiencing very different changes in our local climates. And also definitely worsening of some climate hazards and possibly reversibility in others, so a very different risk landscape as well, emerging post net-zero – and I think we still don’t know very much about that as well.

The post Experts: The key ‘unknowns’ of overshooting the 1.5C global-warming limit appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Experts: The key ‘unknowns’ of overshooting the 1.5C global-warming limit

Climate Change

Cropped 8 October 2025: US government shutdown; EU loses green space; Migratory species extinction threat

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Forest fund delays and cuts

TFFF BEHIND SCHEDULE: Brazil’s flagship forest fund, the Tropical Forest Forever Facility (TFFF), is “running behind schedule as officials deliberate on how to structure the complex financial vehicle” in time for COP30, Bloomberg reported. The “ambitious” fund aims to raise $125bn to help countries protect rainforests “using investment returns from high-yielding fixed-income assets”, it explained. However, the outlet reported that investor events have either not been held or cancelled, while officials are still mulling “possible structures” for the fund.

CUTS DEEP: Environmentalists fear that “sweeping spending cuts for forest protection” by Argentina’s “pro-business libertarian” president, Javier Milei, could endanger the country’s forests, Climate Home News reported. The impacts of these cuts are “already becoming evident”, contributing to deforestation – particularly in the northern Gran Chaco region, environmentalists told the outlet. According to Argentine government data, the country lost about 254,000 hectares of forest nationwide in 2024. Milei – who has said he wants to withdraw Argentina from the Paris Agreement – faces a “crucial midterm election” in October that could make environmental deregulation even easier, the outlet wrote.

BANKING ON THE AMAZON: A new report found that 298 banks around the world “channelled $138.5bn” to companies developing new fossil-fuel projects in Latin America and the Caribbean, Mongabay reported. The experts behind the study told the outlet: “Some major banks have adopted policies to protect the Amazon, but these have had little impact, as they do not apply to corporate-level financing for oil and gas companies operating in the Amazon.” Mongabay approached every bank, but only JPMorgan Chase responded, declining to comment.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “Cropped” email newsletter. A fortnightly digest of food, land and nature news and views. Sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

‘Green to grey’

‘600 FOOTBALL PITCHES’: Europe is losing “green space…at the rate of 600 football pitches a day”, according to a new, cross-border investigation by the “Green to Grey Project”, the Guardian reported. The outlet – part of the Arena for Journalism in Europe collaboration of journalists and scientists behind the project – added that Turkey accounted for more than a fifth of the total loss in Europe. While nature “accounts for the majority of the losses”, the research showed that the EU is also rapidly building on agricultural land, “with grave consequences for the continent’s food security and health”, it continued.

‘TWICE AS HIGH’: Conducted by 40 journalists and scientists from 11 countries, the investigation found that the “natural area” lost to construction in the EU was “twice as high as official estimates”, Le Monde reported. Despite Brussels setting a 2011 target to “reduce the EU’s yearly land take” to 800km2 – “more than 100,000 football fields” – the EU is “artificialising more than 1,000km2 of land per year”, it added.

KEY DRIVERS: While the “main drivers of land loss across Europe” are housing and road-building, Arena for Journalism in Europe found many instances of construction “that serve only a minority or that are not built based on public need”, such as luxury tourism sites. Between 2018 to 2023, “an area the size of Cyprus” in nature and cropland was lost to construction, they added. Researchers who “scrutinised millions of pixels in search of lost natural areas” found that Finland’s tourism boom is “encroaching on the last remaining sanctuaries” in Lapland, another Le Monde story reported.

News and views

‘INTRACTABLE’ OFFSETS: A new review paper found that the failure of carbon offsets to cut emissions is “not due to a few bad apples”, but “down to deep-seated systemic problems that incremental change will not solve”, the Guardian wrote. Study co-author Dr Stephen Lezak told the outlet: “We have assessed 25 years of evidence and almost everything up until this point has failed.” The worst of these “intractable problems” were with “issuing additional credits” for “non-additional”, “impermanent” and double-counted projects, the Guardian noted.

INSTITUTIONALISING AGROECOLOGY: The Cuban government issued a national decree providing a “more explicit legal framework” for the implementation of agroecological principles across the country, according to a release from the Caribbean Agroecology Institute. The decree also announced a new national fund for promoting agroecology. Yamilé Lamothe Crespo, the country’s deputy director of science, innovation and agriculture, “emphasised that agroecology is a model capable of responding to the global climate crisis”, teleSUR reported.

ZERO PROGRESS TO ZERO HUNGER: The world has “made no improvement” towards achieving the “zero hunger” Sustainable Development Goal since it was set in 2015, according to a new report from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. The report said that “ongoing geopolitical tensions and weather-related disruptions” have contributed to “continued instability in global food markets”. Separately, a new report from the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit thinktank estimated that a “year’s worth of bread” has been lost in the UK since 2020 due to extreme weather impacting wheat harvests, the Guardian reported.

MEATLESS MEDIA: More than 96% of analysed climate news stories across 11 (primarily US-based) outlets “made no mention of meat or livestock production as a cause of climate change”, according to analysis by Sentient Media. Sentient, a not-for-profit news organisation in the US, looked at 940 stories to assess the reported causes of greenhouse gas emissions. Around half of the stories included mention of fossil fuels, it said. Covering the report, the Guardian wrote: “The data reveals a media environment that obscures a key driver of the climate crisis.”

FRAUGHT PATH: One-fifth of migratory species “face extinction from climate change”, according to a new report by the UN’s migratory species convention, covered by Carbon Copy. The “warning” comes as climate change and extreme weather are “altering their ranges [and] shrinking habitats”, the Mail & Guardian wrote. Oceanographic Magazine noted that the North Atlantic right whale is “forced to make migratory detours into dangerous pockets of the ocean” due to warming seas. Down to Earth reported that the range of Asian elephants is “shifting east” in “response to anthropogenic land-use and climate change”.

GOODBYE, GOODALL: Dr Jane Goodall, the groundbreaking English primatologist, died at the age of 91 last week. BBC News noted that Goodall “revolutionised our understanding” of chimpanzees, our “closest primate cousins. The outlet added that she “never wavered in her mission to help the animals to which she dedicated her life”. CNBC News reported that Goodall followed a vegan diet due to factory farming and the “damage done to the environment by meat production”. She also “encouraged” others to follow her example, the outlet said.

Spotlight

What the US government shutdown means for food, forests and climate

This week, Carbon Brief explains the US government shutdown – now in its second week – and its implications for food, forests, public lands and climate change.

The US federal government shut down at 12:01 eastern daylight time on 1 October, as Congress failed to agree on a bill to keep funding the government and its services.

This is the 11th time that the government has shut down in such a fashion; previous shutdowns have lasted anywhere from a few hours to longer than a month.

As a result of the shutdown, 750,000 federal employees have been furloughed, or placed on unpaid leave. Others, whose work has been deemed “essential”, are working without pay.

(A law passed during a shutdown in US president Donald Trump’s first term guarantees back pay and benefit accrual for furloughed employees. However, the White House has argued that the law does not necessarily guarantee these benefits.)

Some agencies have seen close to 90% of their employees furloughed.

With a reopening date uncertain, Carbon Brief explored what the shutdown means for food, forests and climate.

Food and farming

According to the agency’s “lapse of funding” plan, the US Department of Agriculture (USDA) planned to furlough about half of its employees for the duration of the shutdown.

Among the activities put on hold during the funding lapse are the disbursement of disaster-assistance payments for farmers impacted by extreme weather events. The Farm Service Agency, which oversees these payments, will also not process any new loans during the shutdown, such as those that provide assistance to farmers during the harvest.

The Natural Resources Conservation Service, an arm of the USDA with a mission to help private landowners “restore, enhance and protect forestland resources”, has seen more than 95% of its staff furloughed, effectively halting all conservation efforts within the agency.

Certain animal-health programmes – such as the one addressing the highly pathogenic avian influenza outbreak – will continue, but others will shutter for the duration of the funding lapse. Long-term research on animal and plant diseases will also cease.

Forests and fires

The US Forest Service falls under the purview of the USDA. Employees responsible for “responding [to] and preparing for wildland fires” will continue to work during the shutdown; however, “hazardous fuels treatments” – such as prescribed burns or pruning to reduce fuel loads – will be reduced under the agency’s plan. Furthermore, state grants for fire preparedness and forest management “may be delayed”.

Work on forest restoration projects may potentially continue “on a case-by-case basis”, the plan said.

The Bureau of Land Management (BLM), a subdivision of the Department of the Interior, will furlough around 43% of its employees, according to its contingency plan. Staff dedicated to fire management will continue to work while “carryover balances” are available, but the number of staff working will be reduced once these funds are exhausted.

Climate change and research

Across the federal government, most research activities are being put on hold, including conference travel and the issuing of new grants.

Grant recipients may continue carrying out research “to the extent that doing so will not require federal staff” and while funds are available, according to the National Science Foundation’s operational plan. This does not include researchers at federal agencies, such as the Environmental Protection Agency, US Geological Survey and the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

The funding-lapse plan set out by the Department of Commerce said that NOAA will continue its prediction and forecasting activities, as well as maintain “critical and mission-related” programmes related to research satellites. However, “most research activities” will cease.

Similarly, NASA’s shutdown plan indicates continuing support for satellite operations, but a pause on research activities – except for those “aligned with presidential priorities”.

Watch, read, listen

MORAINE DILEMMA: A new PBS documentary walked through ancient Inca paths in the Andes to understand how modern communities are confronting the loss of Peru’s glaciers.

SUBSIDISING ‘EXPLOITATION’: A DeSmog investigation revealed how farmers convicted of “exploiting migrant workers” continue to claim “millions in taxpayer-funded subsidies”.

GROUND TRUTHING: A podcast from the Hindu looked back at 20 years of India’s Forest Rights Act, meant to “address historic injustices” towards the country’s Indigenous communities.

DEEP DIVE MANUAL: Mongabay journalists shared how they investigated Brazil’s shark-meat purchases that were subsequently served in schools, prisons and hospitals.

New science

- The frequency of “economically disastrous” wildfires increased sharply after 2015, with the highest disaster risk in “affluent, populated areas” in the Mediterranean and temperate regions | Science

- A “strictly protected” forest in Tuscany had maximum summertime temperatures that were, on average, nearly 2C cooler than those of nearby productive forests over 2013-23 | Agricultural and Forest Meteorology

- Between 2010 and 2020, the water consumed by global crop-growing increased by 9%, putting “additional pressure on limited water resources” | Nature Food

In the diary

- 9-15 October: 2025 World Conservation Congress of the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) | Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates

- 10-17 October: World Food Forum 2025 | Rome

- 16 October: World Food Day | Global

- 25 October: Ivory Coast presidential election

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz. Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 8 October 2025: US government shutdown; EU loses green space; Migratory species extinction threat appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Overshoot: Exploring the implications of meeting 1.5C climate goal ‘from above’

The first-ever international conference on the contentious topic of “overshoot” was held last week in a palace in the small town of Laxenburg in Austria.

The three-day conference brought together nearly 200 researchers and legal experts to discuss future temperature pathways where the Paris Agreement’s “aspirational” target to limit global warming to 1.5C is met “from above, rather than below”.

Overshoot pathways are those which exceed the 1.5C limit – before being brought back down again through techniques that remove carbon from the atmosphere.

The conference explored both the feasibility of overshoot pathways and the legal frameworks that could help deliver them.

Researchers also discussed the potential consequences of a potential rise – and then fall – of global temperatures on climate action, society and the Earth’s climate systems.

Speaking during a plenary session, Prof Joeri Rogelj, a professor of climate science and policy at Imperial College London, said that “moving into a world where we exceed 1.5C and have to manage overshoot” was an exercise in “managing failure”.

He said that it was “essential” that this failure was acknowledged, explaining that this would help set out the need to “minimise and manage” the situation and clarify the implications for “near-term action” and “long-term [temperature] reversal”.

Below, Carbon Brief draws together some of the key talking points, new research and discussions that emerged from the event.

- Defining overshoot

- Mitigation ambition and 1.5C viability

- Carbon removal

- Impacts of overshoot

- Adaptation

- Legal implications and loss and damage

- Communication challenges and next steps

Defining overshoot

The study of temperature overshoot has grown in recent years as the prospects of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5C have dwindled.

Conference organiser Dr Carl-Friedrich Schleussner – a senior research scholar at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) – explained the event was designed to bring together different research communities working on a “new field of science”.

He told Carbon Brief:

“If we look at [overshoot] in isolation, we may miss important parts of the bigger picture. That’s why we also set out the conference with very broad themes and a very interdisciplinary approach.”

The conference was split between eight conference streams: mitigation ambition; carbon dioxide removal (CDR); Earth system responses; climate impacts; tipping points; adaptation; loss and damage; and legal implications.

There was also a focus on how to communicate the concept of overshoot.

In simple English, “overshoot” means to go past or beyond a limit. But, in climate science, the term implies both a failure to meet a target – as well as subsequent action to correct that failure.

Today, the term is most often deployed to describe future temperature trajectories that exceed the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C limit – and then come back down.

(In the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC’s) fifth assessment cycle, completed in 2014, the term was used to describe a potential rise and then fall of CO2 concentrations above levels recommended to meet long-term climate goals. A recent “conceptual” review of overshoot noted this was because, at the time, CO2 concentrations were the key metric used to contextualise emissions reductions).

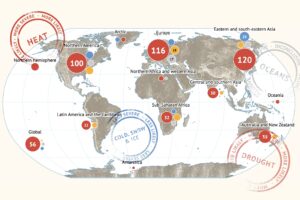

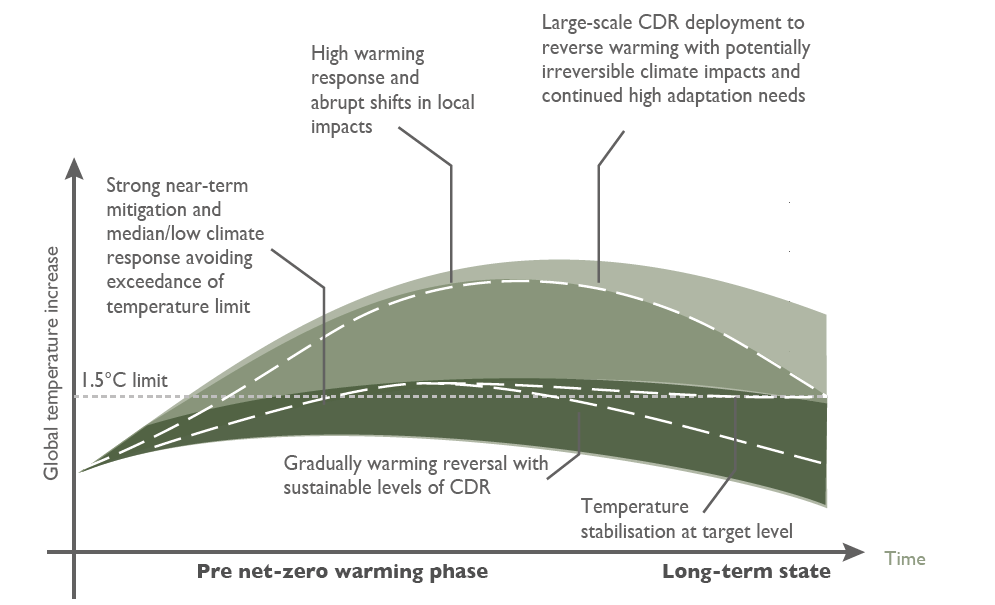

The plot below provides an illustration of three overshoot pathways. The most pronounced pathway sees global temperatures rise significantly above the 1.5C limit – before eventually falling back down again as carbon dioxide is pulled from the atmosphere at scale.

In the second and third pathways, global temperature rise breaches the limit by a smaller margin, before either falling enough just to stabilise around 1.5C, or dropping more dramatically due to larger-scale carbon removals.

In an opening address to delegates, Prof Jim Skea, who is the current chair of the IPCC, acknowledged the scientific interpretation of overshoot was not intuitive to non-experts.

“The IPCC has mainly used two words in relation to overshoot – “exceeding” and “limiting”. To a lay person, these can sound like opposites. Yet we know that a single emissions pathway can both exceed 1.5C in the near term and limit warming to 1.5C in the long term.”

Noting that different research communities were using the term differently, Skea urged researchers to be precise with terminology and stick to the IPCC’s definition of overshoot:

“We should give some thought to communication and keep this as simple as possible. When I look at texts, I hear more poetic words like “surpassing” and “breaching”. I would urge you to keep the range of terms as small as possible and make sure that we’re absolutely using them consistently.”

In the glossary for its latest assessment cycle, AR6, the IPCC defines “overshoot” pathways as follows:

IIASA’s Schleussner stressed that not all pathways that go beyond 1.5C qualify as overshoot pathways:

“The most important understanding is that overshoot is not any pathway that exceeds 1.5C. An overshoot pathway is specific to this being a period of exceedance. It is going to come back down below 1.5C.”

Mitigation ambition and 1.5C viability

Perhaps the most prominent topic during the conference was the implications of overshoot for global ambition to cut carbon emissions and the viability of the 1.5C limit.

Opening the conference, IIASA director general Prof Hans Joachim Schellnhuber shared his personal view that “1.5C is dead, 2C is in agony and 3C is looming”.

In a pre-recorded keynote speech, Ralph Regenvanu, Vanuatu’s minister for climate change, called for a rejection of the “normalisation of overshoot” and argued that “we must treat 1.5C as the absolute limit that it is” and avoid backsliding. He added:

“Minimising peak warming must be our lodestar, because every tenth of a degree matters.”

Prof Skea opened his keynote with some theology:

“I’m going to start with the prayer of St Augustine as he struggled with his youthful longings: ‘Lord grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.’ And it does seem that this is the way that the world as a whole is thinking about 1.5C: ‘Lord, limit warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, but not yet.’”

Referencing the “lodestar” mentioned by Regenvanu, Skea warned that it is light years away and, “unless we act with a sense of urgency, [1.5C is] likely to remain just as remote”.

Speaking to Carbon Brief on the sidelines of the conference, Skea added:

“We are almost certain to exceed 1.5C and the viability of 1.5C is now much more referring to the long-term potential to limit it through overshoot.”

Schleussner told Carbon Brief that the framing of 1.5C in the conference is “one that further solidifies 1.5C as the long-term limit and, therefore, provides a backstop against the idea of reducing or backsliding on targets”.

If warming is going to surpass 1.5C, the next question is when temperatures are going to be brought back down again, Schleussner added, noting that there has been no “direct” guidance on this from climate policy:

“The [Paris Agreement’s] obligation to “pursue efforts” [to limit global temperature rise by 1.5C] points to doing it as fast as possible. Scientifically, we can determine what this means – and that would be this century. But there’s no clear language that gives you a specific date. It needs to be a period of overshoot – that is clear – and it should be as short as possible.”

In a parallel session on the “highest possible mitigation ambition under overshoot”, Prof Joeri Rogelj, professor of climate science and policy at Imperial College London, outlined how the recent ruling from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) provides guidance to countries on the level of ambition in their climate pledges under the Paris Agreement, known as “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs). He explained:

“[The ruling] highlights that the level of NDC ambition is not purely discretionary to a state and that every state must do its utmost to ensure its NDC reflects the highest possible ambition to meet the Paris Agreement long-term temperature goal.”

Rogelj presented some research – due to be published in the journal Environmental Research Letters – on translating the ICJ’s guidance “into a framework that can help us to assess whether an NDC indeed is following a standard of conduct that can represent the highest level of ambition”. He showed some initial results on how the first two rounds of NDCs measure up against three “pillars” covering domestic, international and implementation considerations.

In the same session, Prof Oliver Geden, senior fellow and head of the climate policy and politics research cluster at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs and vice-chair of IPCC Working Group III, warned that the concept of returning temperatures back down to 1.5C after an overshoot is “not a political project yet”.

He explained that there is “no shared understanding that, actually, the world is aiming for net-negative”, where emissions cuts and CDR together mean that more carbon is being taken out of the atmosphere than is being added. This is necessary to achieve a decline in global temperatures after surpassing 1.5C.

This lack of understanding includes developed countries, which “you would probably expect to be the frontrunners”, Geden said, noting that Denmark is the “only developed country that has a quantified net-negative target” of emission reductions of 110% in 2050, compared to 1990 levels. (Finland also has a net-negative target, while Germany announced its intention to set one last year. In addition, a few small global-south countries, such as Panama, Suriname and Bhutan, have already achieved net-negative.)

Geden pondered whether developed countries are a “little bit wary to commit to going to net-negative territory because they fear that once they say -110%, some countries will immediately demand -130% or -150%” to pay back a larger carbon debt.

Carbon removal

To achieve a decline in global temperatures after an initial breach of 1.5C would require the world to reach net-negative emissions overall.

There is a wide range of potential techniques for removing CO2 from the atmosphere, such as afforestation, direct air capture and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). Captured carbon must be locked away indefinitely in order to be effective at reducing global temperatures.

However, despite its importance in achieving net-negative emissions, there are “huge knowledge gaps around overshoot and carbon dioxide removal”, Prof Skea told Carbon Brief. He continued:

“As it’s very clear from the themes of this conference, we don’t altogether understand how the Earth would react in taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. We don’t understand the nature of the irreversibilities. And we don’t understand the effectiveness of CDR techniques, which might themselves be influenced by the level of global warming, plus all the equity and sustainability issues surrounding using CDR techniques.”

Skea notes that the seventh assessment cycle of the IPCC, which is just getting underway, will “start to fill these knowledge gaps without prejudging what the appropriate policy response should be”.

Prof Nebojsa Nakicenovic, an IIASA distinguished emeritus research scholar, told Carbon Brief that his “major concern” was whether there would be an “asymmetry” in how the climate would respond to large-scale carbon removal, compared to its response to carbon emissions.

In other words, he explained, would global temperatures respond to carbon removal “on the way down” in the same way they did “on the way up” to the world’s carbon emissions.

Nakicenovic noted that overshoot requires a change in focus to approaching the 1.5C limit “from above, rather than below”.

Schleussner made a similar point to Carbon Brief:

“We may fail to pursue [1.5C] from below, but it doesn’t relieve us from the obligation to then pursue it from above. I think that’s also a key message and a very strong overarching message that’s going to come out from the conference that we see…that pursuing an overshoot and then decline trajectory is both an obligation, but it also is well rooted in science.”

Reporting back to the plenary from one of the parallel sessions on CDR, Dr Matthew Gidden, deputy director of the Joint Global Change Research Institute at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, also noted another element of changing focus:

“When we’re talking about overshoot, we have become used to, in many cases, talking about what a net-zero world looks like. And that’s not a world of overshoot. That’s a world of not returning from a peak. And so communicating instead about a net-negative world is something that we could likely be shifting to in terms of how we’re communicating our science and the impacts that are coming out of it.”

On the need for both CDR and emissions cuts, Gidden noted that the discussions in his session emphasised that “CDR should not be at the cost of mitigation ambition”. But, he added, there is still the question of how “we talk about emission reductions needed today, but also likely dependence on CDR in the future”.

In a different parallel session, Prof Geden also made a similar point, noting that “we have to shift CDR from being seen as a barrier to ambition to an enabler of even higher ambition, but not doing that by betting on ever more CDR”.

Among the research presented in the parallel sessions on CDR was a recent study by Dr Jay Fuhrman from the JGCRI on the regional differences in capacity to deploy large-scale carbon removal. Ruben Prütz, from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, presented on the risks to biodiversity from large-scale land-based CDR, which – in some cases – could have a larger impact than warming itself.

In another talk, the University of Oxford’s Dr Rupert Stuart-Smith explored how individual countries are “depending very heavily on [carbon] removals to meet their climate targets”. Stuart-Smith was a co-author on an “initial commentary” on the legal limits of CDR, published in 2023. This has been followed up with a “much more detailed legal analysis”, which should be published “very soon”, he added.

Impacts of overshoot

Since the Paris Agreement and the call for the IPCC to produce a special report on 1.5C, research into the impacts of warming at the aspirational target has become commonplace.

Similarly, there is an abundance of research into the potential impacts at other thresholds, such as 2C, 3C and beyond.

However, there is comparatively little research into how impacts are affected by overshoot.

The conference included talks on some published research into overshoot, such as the chances of irreversible glacier loss and lasting impacts to water resources. There were also talks on work that is yet to be formally published, such as the risks of triggering interacting tipping points under overshoot.

Speaking in a morning plenary, Prof Debra Roberts, a coordinating lead author on the IPCC’s forthcoming special report on climate change and cities and a former co-chair of Working Group II, highlighted the need to consider the implications of different durations and peak temperatures of overshoot.

For example, she explained, it is “important to know” whether the impacts of “overshoot for 10 years at 0.2C above 1.5C are the same as 20 years at 0.1C of overshoot”.

Discussions during the conference noted that the answer may be different depending on the type of impact. For heat extremes, the peak temperature may be the key factor, while the length of overshoot will be more relevant for cumulative impacts that build up over time, such as sea level rise.

Similarly, if warming is brought back down to 1.5C after overshoot, what happens next is also significant – whether global temperature is stabilised or net-negative emissions continue and warming declines further. Prof Schleussner told Carbon Brief:

“For example, with coastal adaptation to sea level rise, the question of how fast and how far we bring temperatures back down again will be decisive in terms of the long-term outlook. Knowing that if you stabilise that around 1.5C, we might commit two metres of sea level rise, right? So, the question of how far we can and want to go back down again is decisive for a long-term perspective.”

One of the eight themes of the conference centred specifically on the reversibility or irreversibility of climate impacts.

In his opening speech, Vanuatu’s Ralph Regenvanu warned that “overshooting 1.5C isn’t a temporary mistake, it is a catalyst for inescapable, irreversible harm”. He continued:

“No level of finance can pull back the sea in our lifetimes or our children’s. There is no rewind button on a melted glacier. There is no time machine for an extinct species. Once we cross these tipping points, no amount of later ‘cooling’ can restore our sacred reefs, it cannot regrow the ice that already vanished and it cannot bring back the species or the cultures erased by the rising tides.”

As an example of a “deeply, deeply irreversible” impact, Dr Samuel Lüthi, a postdoctoral research fellow in the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine at the University of Bern, presented on how overshoot could affect heat-related mortality.

Using mortality data from 850 locations across the world, Lüthi showed how projections under a pathway where warming overshoots 1.5C by 0.1-0.3C, before returning to 1.5C by 2100 has 15% more heat-related deaths in the 21st century than a pathway with less than 0.1C of overshoot.

His findings also suggested that “10 years of 1.6C is very similar [in terms of impacts] to five years of 1.7C”.

Extreme heat also featured in a talk by Dr Yi-Ling Hwong, a research scholar at IIASA, on the implications of using solar geoengineering to reduce peak temperatures during overshoot.

She showed that a world where a return to 1.5C had been achieved through geoengineering would see different impacts from a world where 1.5C was reached through cutting emissions. For example, in her modelling study, while geoengineering restores rainfall levels for some regions in the global north, significant drying “is observed in many regions in the global south”.

Similarly, a world geoengineered to 1.5C would see extreme nighttime heat in some tropical regions that is more severe than in a 2C world with no geoengineering, Hwong added.

In short, she said, “this implies the risk of creating winners and losers” under solar geoengineering and “raises concerns about equity and accountability that need to be considered”.

After describing how overshoot features in the outlines of the forthcoming AR7 reports in his opening speech, Prof Skea told Carbon Brief that he expects a “surge of papers” on overshoot in time to be included.

But it was important to emphasise that a “lot of the science that people have been carrying out is relevant within or without an overshoot”, he added:

“At points in the future, we are not going to know whether we’re in an overshoot world or just a high-emissions world, for example. So a lot of the climate research that’s been done is relevant regardless of overshoot. But overshoot is a new kind of dimension because of this issue of focus on 1.5C and concerns about its viability.”

Adaptation

The implications of overshoot temperature pathways for efforts to prepare cities, countries and citizens for the impacts of climate change remains an under-researched field.

Speaking in a plenary, Prof Kristie Ebi – a professor at the University of Washington’s Center for Health and the Global Environment – described research into adaptation and overshoot as “nascent”. However, she stressed that preparing society for the impacts associated with overshoot pathways was as important as bringing down emissions.

She told Carbon Brief that there were “all kinds of questions” about how to approach “effective” adaptation under an overshoot pathway, explaining:

“At the moment, adaptation is primarily assuming a continual increase in global mean surface temperature. If there is going to be a peak – and, of course, we don’t know what that peak is – then how do you start planning? Do you change your planning? There are places, for instance when thinking about hard infrastructure, [where overshoot] may result in a change in your plan.”

IIASA’s Schleussner told Carbon Brief that the scientific community was only just “beginning to appreciate” the need to understand and “quantify” the implications of different overshoot pathways on adaptation.

In a parallel session, Dr Elisabeth Gilmore, associate professor in environmental engineering and public policy at Carleton University in Canada, made the case for overshoot modelling pathways to take greater account of political considerations.

“Not just, but especially, in situations of overshoot, we need to start thinking about this as much as a physical process as a socio-political process…If we don’t do this, we are really missing out on some key uncertainties.”

Current scenarios used in climate research – including the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and Representative Concentration Pathways – are “a bit quiet” when it comes to thinking about governance, institutions and peace and conflict, Gilmore said. She added:

“Political institutions, legitimacy and social cohesion continue to shift over time and this is really going to shape how much we can mitigate, how much we adapt and especially how we would recover when adding in the dimension of overshoot.”

Gilmore argued that, from a social perspective, adaptation needs are greatest “before the peak” of temperature rise – because this is when society can build the resilience to “get to the other side”. She said:

“Orthodoxy in adaptation [research] that you always want to plan for the worst [in the context of adaptation, peak temperature rise]… But we don’t really know what this peak is going to be – and we know that the politics and the social systems are much more messy.”

Dr Marta Mastropietro, a researcher at Politecnico di Milano in Italy, presented the preliminary results of a study that used emulators – simple climate models – to explore how human development might be impacted under low, medium and high overshoot pathways.

Mastropietro noted how, under all overshoot scenarios studied, both the drop to the human development index (HDI) – an index which incorporates health, knowledge and standard of living – and uncertainty increases as the peak temperature increases.

However, she said “the most important takeaway” from the preliminary results was around society’s constrained ability to recover from damage.

“This percentage of damages that are absorbed is always less than 50%. So, even in the most optimistic scenarios of overshoot, we will not be able to reabsorb these damages, not even half of them. And this is considering a damage function which does not consider irreversible impacts like sea level rise.”

Meanwhile, Dr Inês Gomes Marques from the University of Lisboa in Portugal, shared the results of an as-yet-unpublished study investigating whether the Lisbon metropolitan area holds enough public spaces to offer heatwave relief to the population under overshoot scenarios. The 1,900 “climate refugia” counted by researchers included schools, museums and churches.

Marques noted that most of the population were found to be within one kilometre of a “climate refugia” – but noted that “nuances” would need to be added to the analysis, including a function which considers the limited mobility of older citizens.

She explained that the researchers were aiming to “establish a framework” for this type of analysis that would be relevant to both the science community and municipalities tasked with adaptation. She added:

“The main point is that we need to think about this now, because we will face some big problems if we don’t”.

Legal implications and loss and damage

Significant attention was given throughout the conference to the legal considerations of the breach of – and impetus to return to – the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C warming limit.

This included discussions about how the international legal frameworks should be updated for an “overshoot” world where countries would need to pursue “net-negative” strategies to bring temperatures down to 1.5C.

There were also discussions around governance of geoengineering technologies and the fairness and justice considerations that arise from the real-world impacts of breached targets.

The conference was being held just months after the ICJ’s advisory decision that limiting temperature increase to 1.5C should be considered countries’ “primary temperature goal”.

IIASA’s Shleussner told Carbon Brief that the decision provided “clarity” that countries had a “clear obligation to bring warming back to 1.5C”. He added:

“We may fail to pursue it from below, but it doesn’t relieve us from the obligation to then pursue it from above.”

Prof Lavanya Rajamani, professor of international environmental law at the University of Oxford, insisted that “1.5C was very much alive and well in the legal world”, but noted there were “very significant limits” to what could be achieved through the UN Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC) – the global treaty for coordinating the response to climate change – both today and in the future.

Summarising discussions around how countries can be pushed to deliver the “highest possible ambition” in future climate plans submitted to the UN, Rajamani urged delegates to be “tempered in [its] expectations of what we’re going to get from the international regime”. She added:

“Changing the narratives and practices at the national level are far more likely to filter up to the international level than trying to do it from a top-down perspective.”

In a parallel session, Prof Christina Voigt, a professor of international law at the University of Oslo, pointed out that overshoot would require countries to aspire beyond “net-zero emissions” as “the end climate goal” in national plans.

Stabilising emissions at “net-zero” by mid-century would result in warming above 1.5C, she explained, whereas “net-negative” emissions are required to deliver overshoot pathways that return temperatures to below the Paris Agreement’s aspirational limit. She continued:

“We will need frontrunners. Leaders, states, regions would need to start considering negative-emission benchmarks in their climate policies and laws from around mid-century. There will be an expectation that developed country parties take the lead and explore this ‘negativity territory’.”

Voigt added that it was “critical” that nations at the UNFCCC create a “shared understanding” that 1.5C remains the “core target” for nations to aim for, even after it has been exceeded. One possible place for such discussions could be at the 2028 global stocktake, she noted.

She said there would need to be more regulation to scale up CDR in a way that addresses “environmental and social challenges” and an effort to “recalibrate policies and measures” – including around carbon markets – to deliver net-negative outcomes.

In a presentation exploring governance of solar radiation management (SRM), Ewan White, a DPhil student in environmental law at the University of Oxford, said the ICJ’s recent advisory opinion could be interpreted to be “both for and against” solar geoengineering.

Countries tasked with drawing up global rules around SRM in an overshoot world would need to take a “holistic approach to environmental law”, White said. In his view, this should take into account international legal obligations beyond the Paris Agreement and consider issues of intergenerational equity, biodiversity protection and nations’ duty to cooperate.

Dr Shonali Pachauri, research group leader at IIASA, provided an overview of the equity and justice implications that might arise in an overshoot world.

First, she said that delays to emissions reductions today are “shifting the burden” to future generations and “others within this generation” – increasing the need for “corrective justice” and potential loss-and-damage payments.

Second, she said that adaptation efforts would need to increase – which, in turn, would “threaten mitigation ambition” given “constrained decision-making”.

Finally, she pointed to resource consumption issues that might arise in a world of overshoot:

“The different technologies that one might use for CDR often depend on the use of land, water, other materials – and this, of course, then means competing with many other uses [of resources].”

A separate stream focused on loss and damage. Session chair Dr Sindra Sharma, international policy lead at the Pacific Islands Climate Action Network, noted that the concept of loss and damage was “fundamentally transformed” by overshoot – adding there were “deep issues of justice and equity”.

However, Sharma said that the literature on loss and damage “has not yet deeply engaged with the specific concept of overshoot” despite it being “an important, interconnected issue”.