The amount of foreign aid the UK spends on climate action reached a record high of around £3bn last year, according to government figures obtained by Carbon Brief.

However, Carbon Brief analysis shows that more than £500m of this sum comes from controversial changes in the way the UK calculates its climate aid for developing countries.

By leaning on private-sector investment and including existing aid projects in the total, the government is able to inflate its figures without providing as much new climate funding.

Including this money puts the UK on track for its five-year goal of providing £11.6bn by 2026 to support climate action in developing countries, even as it cuts the overall aid budget.

Climate aid – which is often referred to as “international climate finance” (ICF) – will likely still need to rise above £3bn in 2025, if the UK is to achieve its target over the next year.

The new data, released to Carbon Brief via freedom-of-information (FOI) requests, covers provisional 2024-25 spending across the three major government departments that fund climate projects overseas.

This analysis is the latest in a series of articles by Carbon Brief documenting the UK’s ICF contributions since 2011.

Key findings from the most recent year include:

- By far the largest payment last year was a £482.3m contribution to boost British International Investment’s (BII) private-sector interests in developing countries.

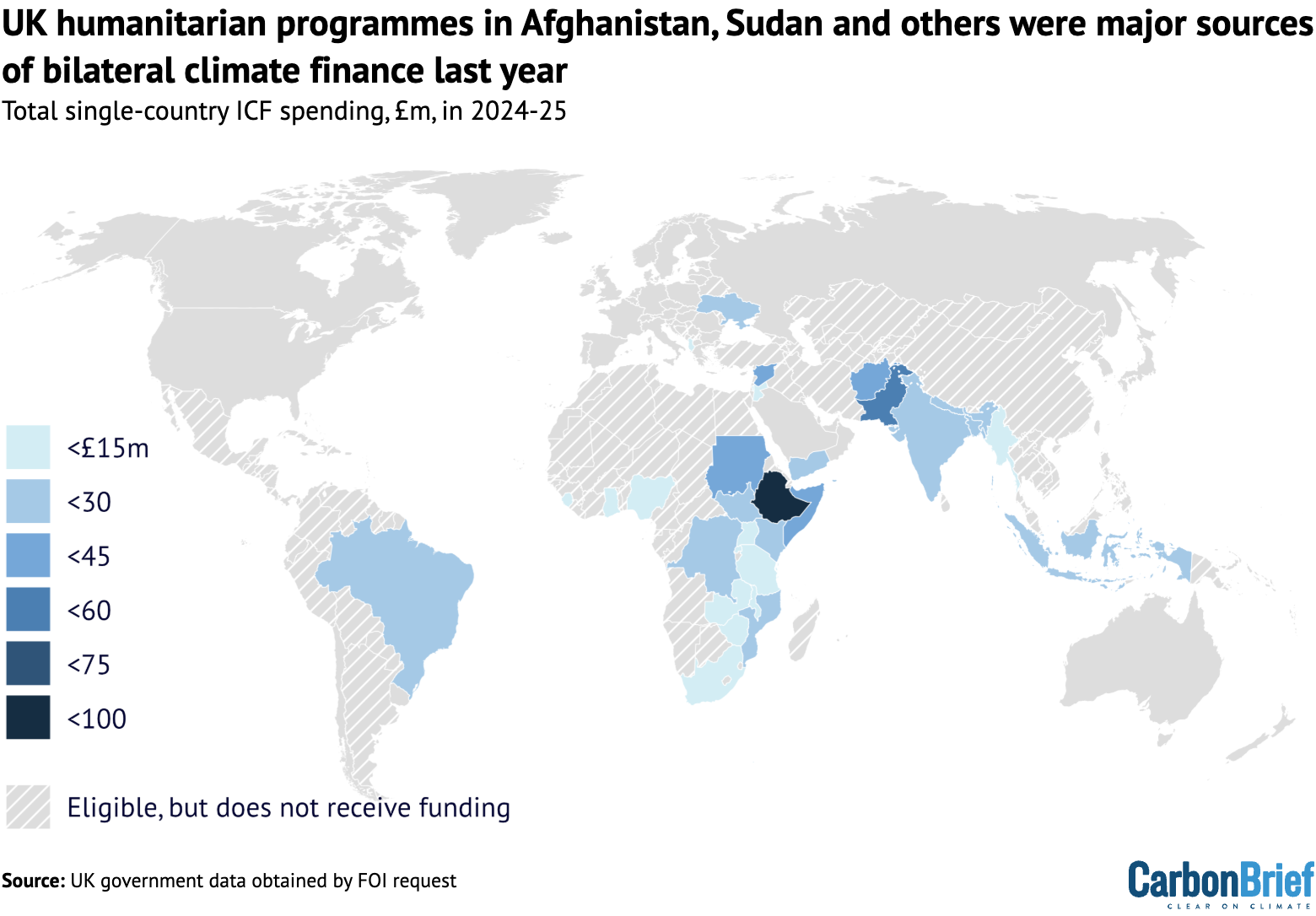

- Ethiopia was the largest recipient of bilateral climate finance (£92.3m). Other major recipients include Pakistan (£55.8m), Afghanistan (£43.7m) and Sudan (£41.1m).

- The biggest single project to receive funding was a World Bank initiative helping developing countries to sell carbon offsets, which received £153.9m.

- Large portions of climate finance also went to the Green Climate Fund (£227m) and the Global Environment Facility (£64.8m).

- Without the government’s changes, which mimic the looser accounting used by some other countries, climate finance would have needed to increase 78% this year. With the changes, climate finance only has to increase by 2%.

- Around £1.3bn – nearly a sixth of the UK’s ICF over the past four years – can be linked to the government’s accounting changes.

Target achieved?

After it was elected last year, Labour confirmed that it would honour the previous government’s pledge to provide £11.6bn of climate finance over the five-year period ending in 2025-26.

This money is the UK’s contribution, under the Paris Agreement, to help developing countries cut emissions and protect themselves from the threat of climate change.

Since the goal was first announced in 2019, experts have regularly voiced doubts that it can be achieved due to major cuts to the foreign-aid budget by successive governments.

More uncertainty followed the announcement in February that the Labour government would cut aid further – from 0.5% of gross national income to 0.3% – ostensibly to fund defence spending. (The government insisted that the remaining aid would “prioritise” climate.)

Despite these changes and uncertainty, the figures provided to Carbon Brief via FOI reveal that the UK is, in fact, on track to meet its £11.6bn target.

Climate-finance spending reached a record high of just under £3bn in the financial year 2024-25, more than £700m higher than the previous year.

(Note that these figures are “provisional” and subject to revision. Due to methodology changes, the final figures for UK climate finance in 2023-24 were much higher than those provided to Carbon Brief via a previous FOI. See the Methodology for more details.)

Assuming the provisional figures for 2024-25 are accurate, the UK would still need to raise its climate finance to £3.1bn in 2025-26 in order to meet the £11.6bn target, as shown in the figure below.

This level of climate finance would need to be maintained, even as the government scales back its overall aid budget in 2025.

When asked at a recent committee hearing whether there would be any new money for the £11.6bn goal, international development minister Baroness Chapman spoke frankly:

“I think the search for new money at the moment is going to be pretty fruitless…Is there going to be any new money for climate in a world where we have just gone from 0.5% to 0.3%? I think you can probably work that out.”

Instead of new funding, the upward trajectory of climate aid has been largely driven by the UK expanding what it counts towards the total. These changes were initially made under the Conservatives, but Labour has retained them.

By relabelling existing funding for multilateral development banks (MDBs), humanitarian aid and private-sector investments via BII as “climate finance”, the UK has inflated the figures without allocating genuinely new funds, making the £11.6bn goal easier to achieve.

Based on data acquired through successive FOIs, Carbon Brief estimates that £528m, or 18% of climate finance provided in 2024-25, can be linked to these accounting changes.

Since 2021, the running total of climate finance resulting from these changes is more than £1.3bn, Carbon Brief analysis suggests, amounting to nearly a sixth of spending to date.

Experts have pointed out that this amounts to a real-world cut in climate aid, as it means less additional funding than was originally pledged.

Without the accounting changes, UK climate finance would only have reached around £2.5bn last year, as the chart below shows.

To achieve the £11.6bn goal from this position, climate finance would have needed to increase by 78% this year, nearly doubling from a year earlier. In comparison, the accounting changes mean it only has to increase by 2%.

The government says that its accounting changes merely brought it in line with other countries. A Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) spokesperson tells Carbon Brief:

“We will continue to account for all of our international climate finance using internationally agreed OECD guidelines. Meeting our £11.6bn commitment by March 2026 remains our ambition and it is only right that we accurately reflect the funding going to support this aim.”

In response, NGOs and aid experts have argued the UK should have retained its former position as a leader in climate-finance accounting standards, rather than aligning with the looser methodologies used by many others, such as Germany and France.

Moreover, the £11.6bn goal was meant to be a doubling of the government’s previous £5.8bn target, which was based on the original accounting methodology. If the previous target had also been based on a broader definition of climate aid, then the current £11.6bn target would have needed to be higher to represent a doubling.

As the UK nears the end of its third five-year ICF target, it is expected to announce another goal covering the period 2026-27 onwards. This will feed into the $300bn global climate finance target that nations agreed at the COP29 climate summit last year.

Amid the aid cuts, climate NGOs say that the accounting changes should be reversed and the UK should turn to “polluter-pays” measures to generate the required public funds. Catherine Pettengell, executive director of Climate Action Network UK, tells Carbon Brief:

“Our main concern is that we now have the spending review, but there is still no clarity – or vision – on current or future climate finance from the UK.”

Big investments

The UK is now leaning heavily on private-sector investments to achieve its climate-finance goals, according to Carbon Brief’s analysis.

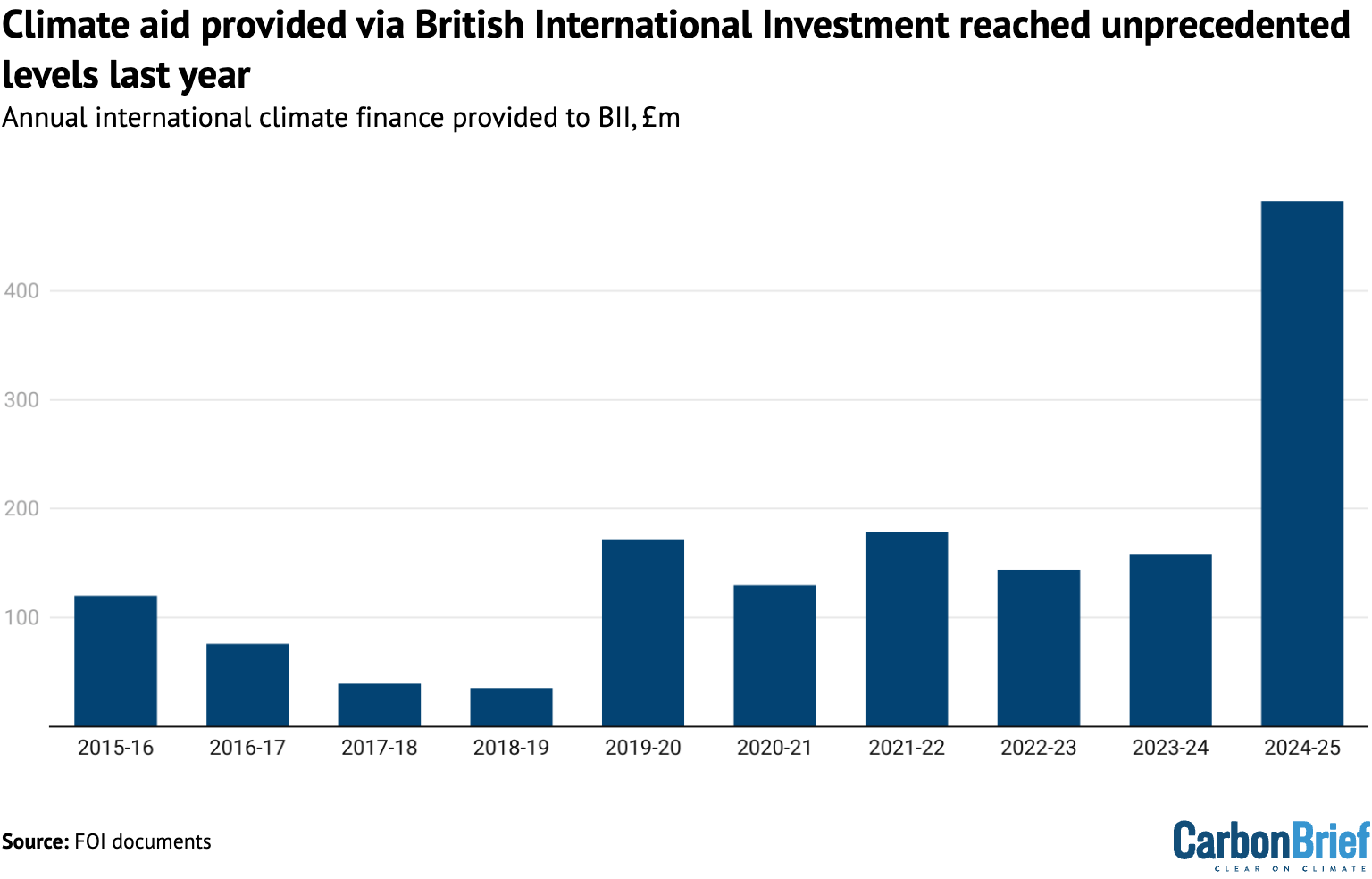

By far the largest climate-finance input last year was a £482m contribution to the UK’s development finance institution, BII.

This is the biggest climate-finance contribution the UK has ever made in a single year, according to the data that Carbon Brief has collected in recent years.

It also amounted to nearly a fifth of the total climate finance last year and almost three times more than the UK has ever channelled into BII before.

BII is a publicly owned, for-profit company that largely supports itself with its £7.3bn portfolio of investments in developing countries, but it also receives regular injections of aid money.

The surge in BII climate finance last year can be attributed to two things.

First, the government now counts more of its BII investments as climate finance than it did previously, following the accounting changes. It argues that this more accurately reflects BII’s expanding focus on investing in clean-energy projects overseas.

The government also decided to invest an extra £400m – largely from underspending on housing asylum seekers in the UK – into BII, bringing its total budget for the year up to £881m.

Prior to these changes, the government expected BII climate finance to be worth £126m in 2024-25, according to forecasts previously obtained by Carbon Brief.

It has, therefore, added an extra £356m to BII’s contribution. Carbon Brief estimates that £218m of this can be attributed to the accounting changes, rather than the increase in funding. (See: Methodology.)

Critics argue that BII, which focuses on loans and equity finance rather than grants, is not capable of supporting climate action in the poorest and most climate-vulnerable nations. (Separately, it has also been criticised for continuing to support fossil-fuel developments.)

Last week’s spending review provided the FCDO with at least £300m annually out to 2029-30 for BII and similar organisations, even as billions are cut from its aid budget. In this context, Ian Mitchell, a senior policy fellow at the Center for Global Development, tells Carbon Brief:

“BII looks set to become the government’s main climate-finance vehicle. Though, whether this is compatible with its historic focus on Africa and the poorest countries remains to be seen.”

Meanwhile, the biggest single project to receive funding from the UK last year was the World Bank initiative titled: “Scaling Climate Action by Lowering Emissions (SCALE).” The government provided it with an initial contribution of £154m.

SCALE aims to help around 20 countries generate carbon credits that can be sold by companies on the voluntary offset market or internationally via Article 6 carbon markets.

According to the UK government, one aim is to “maximise the mobilisation of additional finance through the sale of carbon credits”.

Selling carbon offsets has long been touted as a way to channel climate finance into developing countries, but the practice has faced intense scrutiny and accusations of “greenwashing” in recent years.

Accounting changes

Other large portions of funding in the UK’s 2024-25 climate-finance budget can also be attributed to changes in the government’s accounting methodology.

For example, as of 2023, the UK started counting portions of its “core” payments into MDBs as climate finance, significantly inflating its climate-aid total.

This money is used by the banks to issue loans and – to a lesser extent – grants for projects in developing countries. While many of these projects will be climate-related, relabelling some of the UK’s contributions as “climate finance” does not result in any additional funds being distributed.

In 2024-25, this relabelling accounted for at least £103m of the total climate finance, including £84m for the African Development Bank (AfDB), £11m for the Asian Development Bank (ADB) and £8m for the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB) Special Development Fund.

In terms of bilateral aid from the UK, several of the projects with the largest share of climate finance last year were in nations facing war, famine and natural disasters.

This can partly be attributed to accounting changes that mean 30% of all humanitarian funding in the most climate-vulnerable countries – including Afghanistan, Sudan and Somalia – is now automatically counted as climate finance within government accounting.

Some of these nations have, therefore, risen to be top recipients of bilateral “climate aid” from the UK – as shown in the figure below – through programmes such as Sudan Humanitarian Preparedness and Response.

(Such programmes tend to involve the UK supporting NGOs rather than providing funds to governments. For example, FCDO has two “flagship” humanitarian programmes in Afghanistan – both with an ICF component – but does not provide funds to the Taliban.)

This accounting change was viewed by the previous Conservative government as a way to avoid a “trade-off” between climate and humanitarian projects, amid aid budget cuts.

As the map above shows, Ethiopia remained the largest recipient of UK climate finance via single-country projects last year, with £92.3m in total. This has been the case for more than a decade.

The finance largely comes from two programmes, which aim to improve climate resilience in regions of Ethiopia that have been afflicted by drought and flooding. The country has faced years of regional conflicts that have been exacerbated by climate shocks.

Rather than directly supporting individual projects in individual countries, most UK climate finance is distributed to international bodies and initiatives that serve many countries.

Some of the biggest payments are to well-established international grant providers. These include £227m for the Green Climate Fund, £64m for the Global Environment Facility and £26m for the Global Biodiversity Framework Fund (GBFF).

Other large payments went to long-running initiatives to help “build financial markets and institutions” in Africa and “mobilise private investment in infrastructure” in developing countries.

Methodology

This analysis is the latest part of Carbon Brief’s efforts to assess the UK’s ICF contributions by financial year. Detailed data underpinning these contributions is not released publicly, but is required to track progress towards the UK’s ICF targets.

Total ICF figures for the years 2011-12 to 2023-24 are based on summary public statements made by the government. Ministers have quoted different figures on different occasions, but Carbon Brief is using a March statement from FCDO minister Stephen Doughty for the 2011-12 to 2023-24 period, as this is understood to be the most up-to-date.

The figures for 2024-25 are based on FOI responses from the three major departments responsible for the UK’s overseas climate-related aid projects: FCDO, the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ) and the Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (Defra). Around 80% of climate finance provided by the UK is overseen by the FCDO.

All three of these departments provided the data for 2024-25, stressing that it is provisional. This means it is “subject to year-end accounting and audit adjustments, which are still being processed”. Carbon Brief also received the final (i.e. non-provisional) figures for 2023-24, having been given the provisional figures last year.

(The provisional figures released to Carbon Brief in 2023-24 last year were significantly lower than the final figures – amounting to £1.8bn rather than £2.3bn. This is almost entirely due to the provisional data not factoring in most of the accounting methodology changes described in this article. The provisional figures for 2024-25 appear to have factored in these methodology changes already.)

The Department for Science, Innovation and Technology (DSIT) also oversees a small number of ICF projects overseas. Unlike the other departments, DSIT rejected Carbon Brief’s FOI requests. Carbon Brief understands that its projects were worth £42m in 2023-24, roughly 1% of the total. For the sake of this analysis, Carbon Brief assumes that this amount remained the same in 2024-25.

Carbon Brief relied on previous FOI results to calculate how much of the UK’s climate finance derives from accounting changes in recent years:

- BII: According to an internal document, under its old methodology, the government originally forecast 30% of BII core capital to be climate finance in 2024-25, amounting to £126m. The final figure provided to Carbon Brief, which is also based on a higher core capital figure, is £482m. If the government had counted 30% of the higher core capital contribution as ICF, under its old methodology, the total would be £264.3. This suggests the remaining £218m of the £482m could be attributed to the methodology changes.

- MDBs: The FOI results provided to Carbon Brief show contributions to the AfDB, ADB and CDB amounting to £103m.

- Humanitarian projects: Carbon Brief has used the estimates from an internal document showing how much climate finance the government expects humanitarian aid projects to provide, including £69m in 2024-25. This may be an underestimate, as some of the projects listed in this document have higher ICF totals in the new FOI data released to Carbon Brief.

- “Scrubbed” projects: The government also asked civil servants to reappraise the existing aid portfolio in order to identify any extra ICF that could be counted. Carbon Brief has obtained an incomplete list of these projects, which states that £138m was added to the 2024-25 total in this way.

Together, these changes add up to £528m. The actual figure may be higher, as these are provisional figures.

Carbon Brief’s estimate of the cumulative impact of the accounting changes by 2024-25 – some £1.3bn – aligns with an estimate of £1.72bn for the entire five-year period out to 2025-26, made by the Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI). The final figure may be higher, as ICAI’s calculation was based on government documents that did not, for example, include the increased capital contribution to BII in 2024-25.

The post Analysis: UK climate aid to hit £11.6bn goal – but only due to accounting rule change appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: UK climate aid to hit £11.6bn goal – but only due to accounting rule change

Climate Change

Efforts to green lithium extraction face scrutiny over water use

Mining companies are showcasing new technologies which they say could extract more lithium – a key ingredient for electric vehicle (EV) batteries – from South America’s vast, dry salt flats with lower environmental impacts.

But environmentalists question whether the expensive technology is ready to be rolled out at scale, while scientists warn it could worsen the depletion of scarce freshwater resources in the region and say more research is needed.

The “lithium triangle” – an area spanning Argentina, Bolivia and Chile – holds more than half of the world’s known lithium reserves. Here, lithium is found in salty brine beneath the region’s salt flats, which are among some of the driest places on Earth.

Lithium mining in the region has soared, driven by booming demand to manufacture batteries for EVs and large-scale energy storage.

Mining companies drill into the flats and pump the mineral-rich brine to the surface, where it is left under the sun in giant evaporation pools for 18 months until the lithium is concentrated enough to be extracted.

The technique is relatively cheap but requires vast amounts of land and water. More than 90% of the brine’s original water content is lost to evaporation and freshwater is needed at different stages of the process.

One study suggested that the Atacama Salt Flat in Chile is sinking by up to 2 centimetres a year because lithium-rich brine is being pumped at a faster rate than aquifers are being recharged.

Lithium extraction in the region has led to repeated conflicts with local communities, who fear the impact of the industry on local water supplies and the region’s fragile ecosystem.

The lithium industry’s answer is direct lithium extraction (DLE), a group of technologies that selectively extracts the silvery metal from brine without the need for vast open-air evaporation ponds. DLE, it argues, can reduce both land and water use.

Direct lithium extraction investment is growing

The technology is gaining considerable attention from mining companies, investors and governments as a way to reduce the industry’s environmental impacts while recovering more lithium from brine.

DLE investment is expected to grow at twice the pace of the lithium market at large, according to research firm IDTechX.

There are around a dozen DLE projects at different stages of development across South America. The Chilean government has made it a central pillar of its latest National Lithium Strategy, mandating its use in new mining projects.

Last year, French company Eramet opened Centenario Ratones in northern Argentina, the first plant in the world to attempt to extract lithium solely using DLE.

Eramet’s lithium extraction plant is widely seen as a major test of the technology. “Everyone is on the edge of their seats to see how this progresses,” said Federico Gay, a lithium analyst at Benchmark Mineral Intelligence. “If they prove to be successful, I’m sure more capital will venture into the DLE space,” he said.

More than 70 different technologies are classified as DLE. Brine is still extracted from the salt flats but is separated from the lithium using chemical compounds or sieve-like membranes before being reinjected underground.

DLE techniques have been used commercially since 1996, but only as part of a hybrid model still involving evaporation pools. Of the four plants in production making partial use of DLE, one is in Argentina and three are in China.

Reduced environmental footprint

New-generation DLE technologies have been hailed as “potentially game-changing” for addressing some of the issues of traditional brine extraction.

“DLE could potentially have a transformative impact on lithium production,” the International Lithium Association found in a recent report on the technology.

Firstly, there is no need for evaporation pools – some of which cover an area equivalent to the size of 3,000 football pitches.

“The land impact is minimal, compared to evaporation where it’s huge,” said Gay.

The process is also significantly quicker and increases lithium recovery. Roughly half of the lithium is lost during evaporation, whereas DLE can recover more than 90% of the metal in the brine.

In addition, the brine can be reinjected into the salt flats, although this is a complicated process that needs to be carefully handled to avoid damaging their hydrological balance.

However, Gay said the commissioning of a DLE plant is currently several times more expensive than a traditional lithium brine extraction plant.

“In theory it works, but in practice we only have a few examples,” Gay said. “Most of these companies are promising to break the cost curve and ramp up indefinitely. I think in the next two years it’s time to actually fulfill some of those promises.”

Freshwater concerns

However, concerns over the use of freshwater persist.

Although DLE doesn’t require the evaporation of brine water, it often needs more freshwater to clean or cool equipment.

A 2023 study published in the journal Nature reviewed 57 articles on DLE that analysed freshwater consumption. A quarter of the articles reported significantly higher use of freshwater than conventional lithium brine mining – more than 10 times higher in some cases.

“These volumes of freshwater are not available in the vicinity of [salt flats] and would even pose problems around less-arid geothermal resources,” the study found.

The company tracking energy transition minerals back to the mines

Dan Corkran, a hydrologist at the University of Massachusetts, recently published research showing that the pumping of freshwater from the salt flats had a much higher impact on local wetland ecosystems than the pumping of salty brine. “The two cannot be considered equivalent in a water footprint calculation,” he said, explaining that doing so would “obscure the true impact” of lithium extraction.

Newer DLE processes are “claiming to require little-to-no freshwater”, he added, but the impact of these technologies is yet to be thoroughly analysed.

Dried-up rivers

Last week, Indigenous communities from across South America held a summit to discuss their concerns over ongoing lithium extraction.

The meeting, organised by the Andean Wetlands Alliance, coincided with the 14th International Lithium Seminar, which brought together industry players and politicians from Argentina and beyond.

Indigenous representatives visited the nearby Hombre Muerto Salt Flat, which has borne the brunt of nearly three decades of lithium extraction. Today, a lithium plant there uses a hybrid approach including DLE and evaporation pools.

Local people say the river “dried up” in the years after the mine opened. Corkran’s study linked a 90% reduction in wetland vegetation to the lithium’s plant freshwater extraction.

Pia Marchegiani, of Argentine environmental NGO FARN, said that while DLE is being promoted by companies as a “better” technique for extraction, freshwater use remained unclear. “There are many open questions,” she said.

AI and satellite data help researchers map world’s transition minerals rush

Stronger regulations

Analysts speaking to Climate Home News have also questioned the commercial readiness of the technology.

Eramet was forced to downgrade its production projections at its DLE plant earlier this year, blaming the late commissioning of a crucial component.

Climate Home News asked Eramet for the water footprint of its DLE plant and whether its calculations excluded brine, but it did not respond.

For Eduardo Gigante, an Argentina-based lithium consultant, DLE is a “very promising technology”. But beyond the hype, it is not yet ready for large-scale deployment, he said.

Strong regulations are needed to ensure that the environmental impact of the lithium rush is taken seriously, Gigante added.

In Argentina alone, there are currently 38 proposals for new lithium mines. At least two-thirds are expected to use DLE. “If you extract a lot of water without control, this is a problem,” said Gigante. “You need strong regulations, a strong government in order to control this.”

The post Efforts to green lithium extraction face scrutiny over water use appeared first on Climate Home News.

Efforts to green lithium extraction face scrutiny over water use

Climate Change

Maryland’s Conowingo Dam Settlement Reasserts State’s Clean Water Act Authority but Revives Dredging Debate

The new agreement commits $340 million in environmental investments tied to the Conowingo Dam’s long-term operation, setting an example of successful citizen advocacy.

Maryland this month finalized a $340 million deal with Constellation Energy to relicense the Conowingo Dam in Cecil County, ending years of litigation and regulatory uncertainty. The agreement restores the state’s authority to enforce water quality standards under the Clean Water Act and sets a possible precedent for dozens of hydroelectric relicensing cases nationwide expected in coming years.

Climate Change

A Michigan Town Hopes to Stop a Data Center With a 2026 Ballot Initiative

Local officials see millions of dollars in tax revenue, but more than 950 residents who signed ballot petitions fear endless noise, pollution and higher electric rates.

This is the second of three articles about Michigan communities organizing to stop the construction of energy-intensive computing facilities.

A Michigan Town Hopes to Stop a Data Center With a 2026 Ballot Initiative

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Greenhouse Gases1 year ago

Greenhouse Gases1 year ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Greenhouse Gases2 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change1 year ago

Climate Change1 year ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Renewable Energy3 months ago

US Grid Strain, Possible Allete Sale