Developing countries are receiving just a fraction of the international finance they need to prepare citizens and adapt infrastructure for escalating climate impacts.

That is according to the latest adaptation gap report from the UN Environment Programme (UNEP), which calculates that developing nations will need more than $310bn annually between now and 2035 to prepare for the impacts of climate change.

And yet, in 2023, developed nations provided just $26bn in international adaptation finance to developing nations, according to the report.

UNEP warns that, under current trends, developed nations are on track to miss their goal – agreed at the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow – of doubling 2019 international adaptation finance by 2025.

It cautions that countries’ more recent climate-finance pledge for 2035 – the new collective quantified goal (NCGQ) – will be “insufficient” to meet adaptation finance needs.

The UN report – entitled, “Running on empty: The world is gearing up for climate resilience without the money to get there” – also explores how countries are integrating adaptation priorities into national climate plans, policies and practices.

It finds that 87% of countries have at least one national adaptation plan or strategy in place, but warns that gaps remain in the implementation of measures.

Inger Andersen, the executive director of UNEP, says: “Even amid tight budgets and competing priorities, the reality is simple: if we do not invest in adaptation now, we will face escalating costs every year.”

Below, Carbon Brief summarises some of the key takeaways from the report.

- Developed countries are on track to miss their 2025 adaptation finance goal

- Developing nations’ adaptation finance needs are 12 times greater than current flows

- A majority of countries have a national adaptation plan or strategy in place

- Implementation of adaptation measures is progressing – but gaps remain

- The NCQG is insufficient on its own to meet adaptation finance needs

Developed countries are on track to miss their 2025 adaptation finance goal

Climate change adaptation refers to a range of measures that reduce society’s and infrastructure’s vulnerability to climate change, from planting crop varieties that can withstand greater heat through to building stronger defences against floods.

Spending from the public funds of developed nations is a key source of finance for these actions in developing nations, especially for low-income countries that are vulnerable to climate impacts.

Under Article 9 of the Paris Agreement, developed countries agreed to achieve a “balance” in the amount of climate finance raised for emissions reduction and adaptation. However, more money has been raised for cutting emissions than preparing for climate impacts.

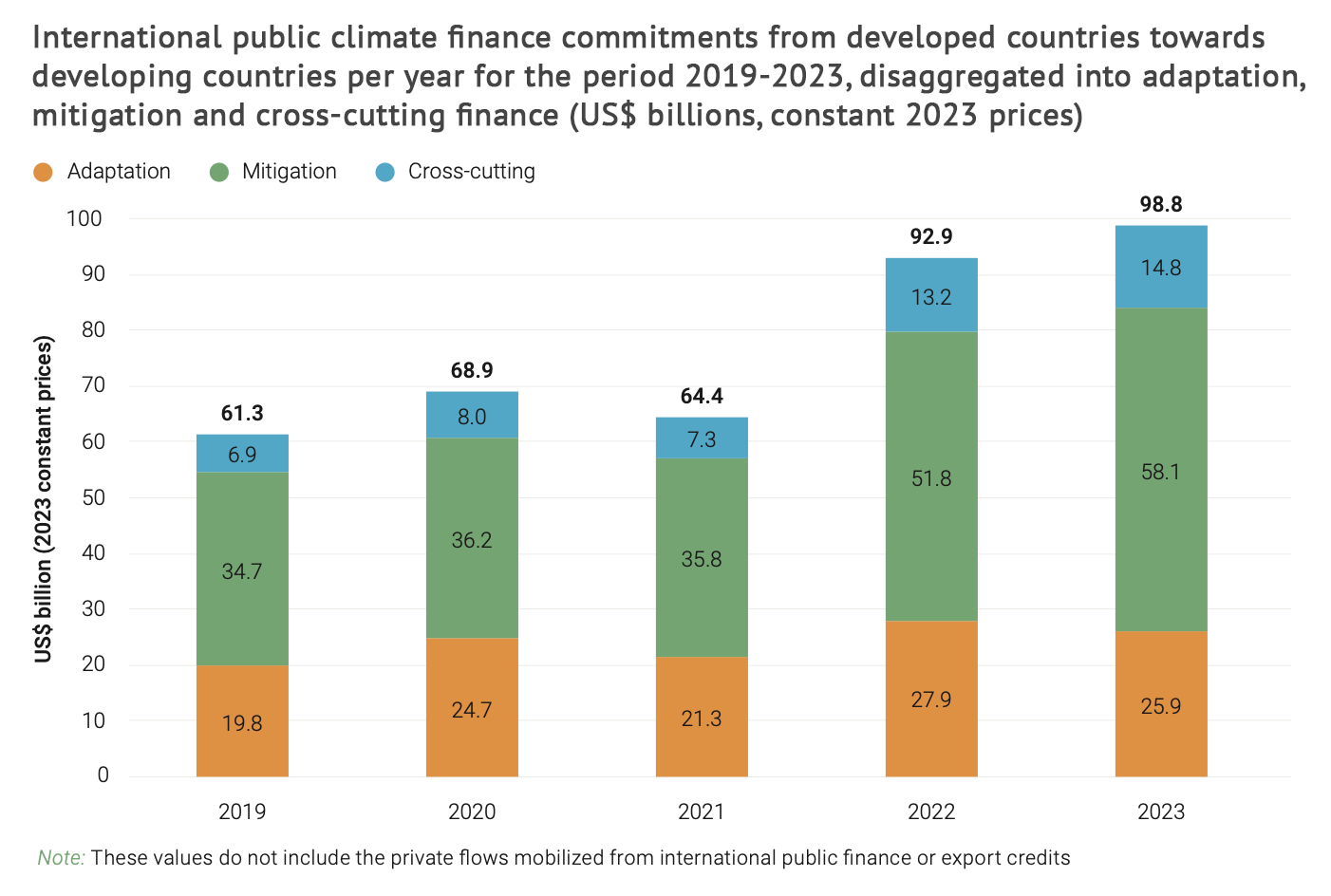

UNEP’s adaptation gap report notes that, in 2023, the amount of public money channelled to developing countries from richer nations for adaptation measures fell.

In total, developed countries raised $25.9bn in international adaptation finance – marking a decline on the $27.9bn recorded in 2022.

The report authors attribute the fall to a decline in funding from multilateral development banks, such as the World Bank, which provided more than half – 57% – of international adaptation finance.

The table below shows how adaptation finance provided by developed countries for developing countries (orange) dipped in 2023 – despite an uptick in climate finance as a whole.

The UN warns that, if current trends continue, developed nations are set to miss their goal of doubling 2019 adaptation finance flows by 2025.

This goal – set out in the Glasgow Climate Pact agreed at the COP26 climate summit in 2021 – commits developed nations to providing $40bn in adaptation funding for developing nations by 2025.

Official climate-finance figures from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) for 2025 will not be available for several years. However, the report notes that, over 2019-23, international adaptation finance grew at a compound rate of 7% – falling short of the 12% rate required to meet the Glasgow Climate Pact goal.

Cuts to international aid budgets since 2023 are also threatening the Glasgow Climate Pact goal, according to the report authors. They note that, globally, foreign aid fell by 9% in 2024 and predict that reductions announced in 2025 are “likely” to lead to a further 9-17% decline.

Meanwhile, countries’ more recent pledge to help raise $300bn a year by 2035 for both tackling and adapting to climate change – set out in the new collective quantified goal for climate finance (NCQG), agreed last year at COP29 in Baku – is also under threat, according to the report.

In the introduction of the report, UNEP’s Anderson writes:

“While the numbers for 2024 and 2025 are not yet available, one thing is clear: unless trends in adaptation financing do not turn around, which currently seems unlikely, the Glasgow Climate Pact goal will not be achieved, the NCQG will not be achieved and many more people will suffer needlessly.”

‘Adaptation investment trap’

The report also breaks down international adaptation finance in 2023 by funding type. It finds that that 70% was either grants, which allow countries to address climate impacts without exacerbating debt, or “concessional” loans, which are provided at below market rate.

However, it notes that “non-consessional” finance – which is provided at, or near, market rates – is on the rise, growing at an annual compound rate of 7% over 2019-23. In 2023, non-concessional loans exceeded concessional ones for the first time, the report notes.

The “increasing proportion” of non-concessional finance raises “long-term affordability and equity” concerns, the authors warn. They also point to the risk of an “adaptation investment trap” – whereby rising climate disasters increase developing countries’ “indebtedness”, which subsequently makes it harder for them to invest in adaptation.

The report also finds that loans and other forms of “debt instruments” comprised “58% on average” of international adaptation finance in 2022-23.

The NCQG text highlights the need for “concessional” and “non-debt creating” finance.

(This came after strong calls from many developing countries to exclude “non-concessional” loans – which result in wealth flowing back to the donor countries as loan repayments and interest – as a form of climate finance. Analysis has shown that many developing countries are spending more on servicing debts than they receive in climate finance.)

Elsewhere, the authors also find that funding for new adaptation projects through UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) funds (the adaptation fund, green climate fund (GCF) and the least developed countries fund (LDCF) and special climate change fund (SCCF) managed by the Global Environment Facility) saw a “large spike” in 2024, with grants reaching around $920m.

However, they note that the recent increase “may not be a trend, with financial constraints likely to rise beyond 2025”.

Developing nations’ adaptation finance needs are 12 times greater than current flows

While previous UN adaptation gap reports have investigated adaptation finance shortfalls through to 2030, this latest analysis extends its estimates through to 2035.

This is in light of the NCQG, which states that developed countries should “take the lead” in raising “at least $300bn” a year for climate action in developing countries by 2035.

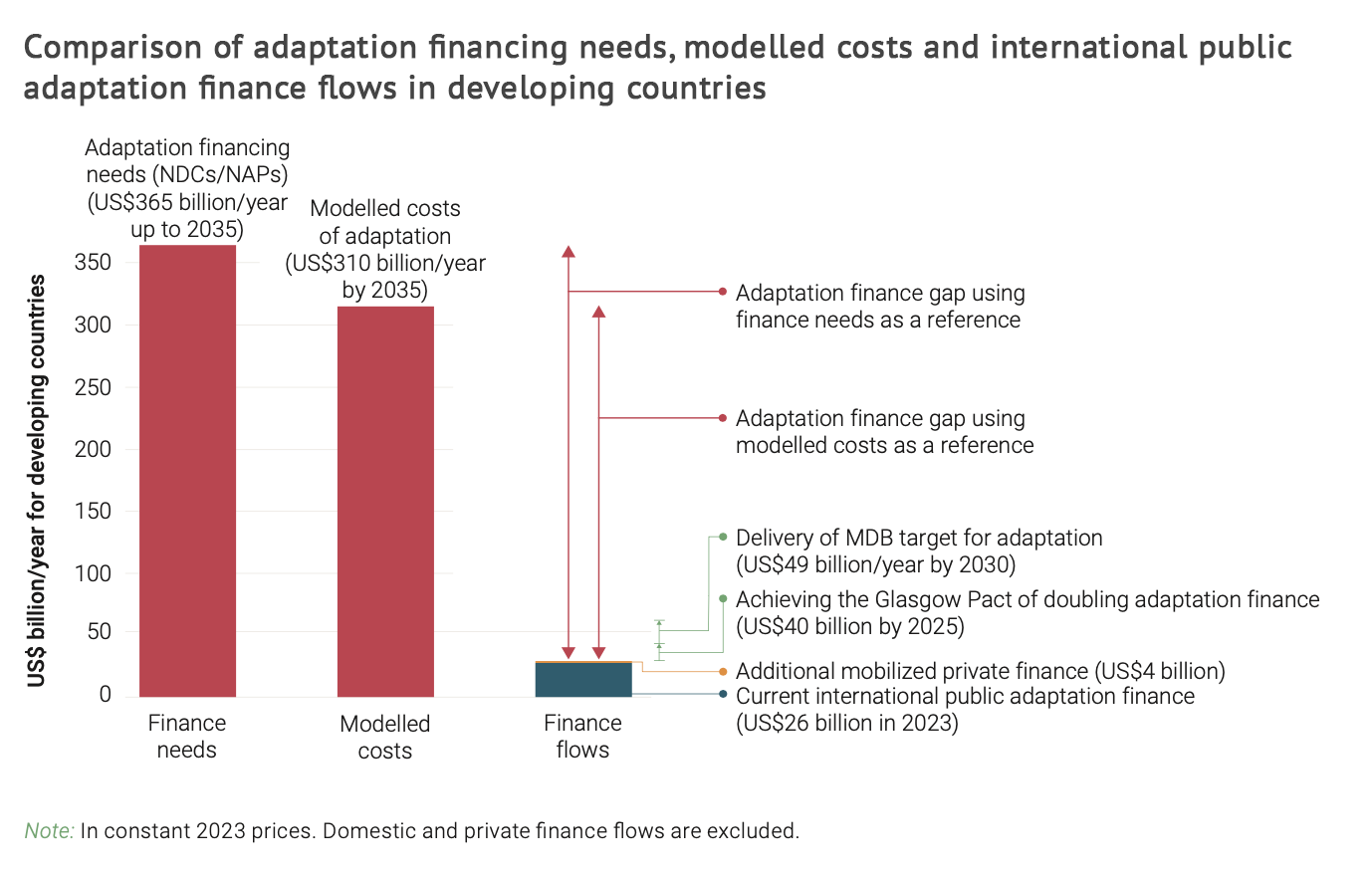

The report calculates that the costs of adaptation by 2035 for developing countries sit in a “plausible central range” of $310-365bn annually. It explains that it has arrived at this range based on “two lines of evidence”:

- A modelled estimate of the additional costs of adaptation, calculated using “global sectoral models with national-level resolution”. This exercise pins the cost of adaptation for developing countries at $310bn a year by 2035 under an intermediate emissions scenario.

- An analysis of the climate finance needs set out by developing countries in 97 national adaptation plans and nationally determined contributions (NDCs) submitted to the UNFCCC – with “extrapolation” of this data to all 155 developing countries. This results in the upper figure of $365bn per year up to 2035.

The chart below shows the disparity between existing finance flows (dark blue bar) and adaptation finance needs and modelled costs (red bars).

With current levels of international adaptation finance estimated at $26bn a year, the report calculates that developing countries are facing an “adaptation finance gap” in the range of $284-339bn per year by 2035.

As such, it calculates that the adaptation finance needs of developing countries by 2035 are “12-14 times” as much as current finance flows.

Of the public adaptation finance that has been issued, a higher proportion currently goes to the countries most exposed to climate hazards, according to the report. It notes that, in 2022-23, $10.4bn and $1.2bn was allocated to least-developed countries (LDCs), including Afghanistan and Rwanda, and small island developing states (SIDS), such as Tuvalua and the Marshall Islands, respectively.

Nevertheless, finance provided to these climate-vulnerable nations is still “modest relative to needs”, the report warns. It estimates that the adaptation finance needs of LDCs and SIDS are $50bn a year.

It also finds that per-capita adaptation finance to both country groups was lower in 2022-23 than previous years, at $9 for LDCs and $20 in SIDs.

A majority of countries have a national adaptation plan or strategy in place

Under the framework for the global goal on adaptation agreed at COP28, countries said they would put in place “national adaptation plans, policy instruments and planning processes and/or strategies” by 2030.

To assess the “global status” of national adaptation planning, the authors of the report tracked the publication of national plans, strategies and policies for adaptation in each country.

According to the report, the first national adaptation policy was published in 2002. It finds that there was a “notable acceleration” in countries developing national adaptation planning instruments over 2011-21, but says that, since then, progress has “slowed significantly”.

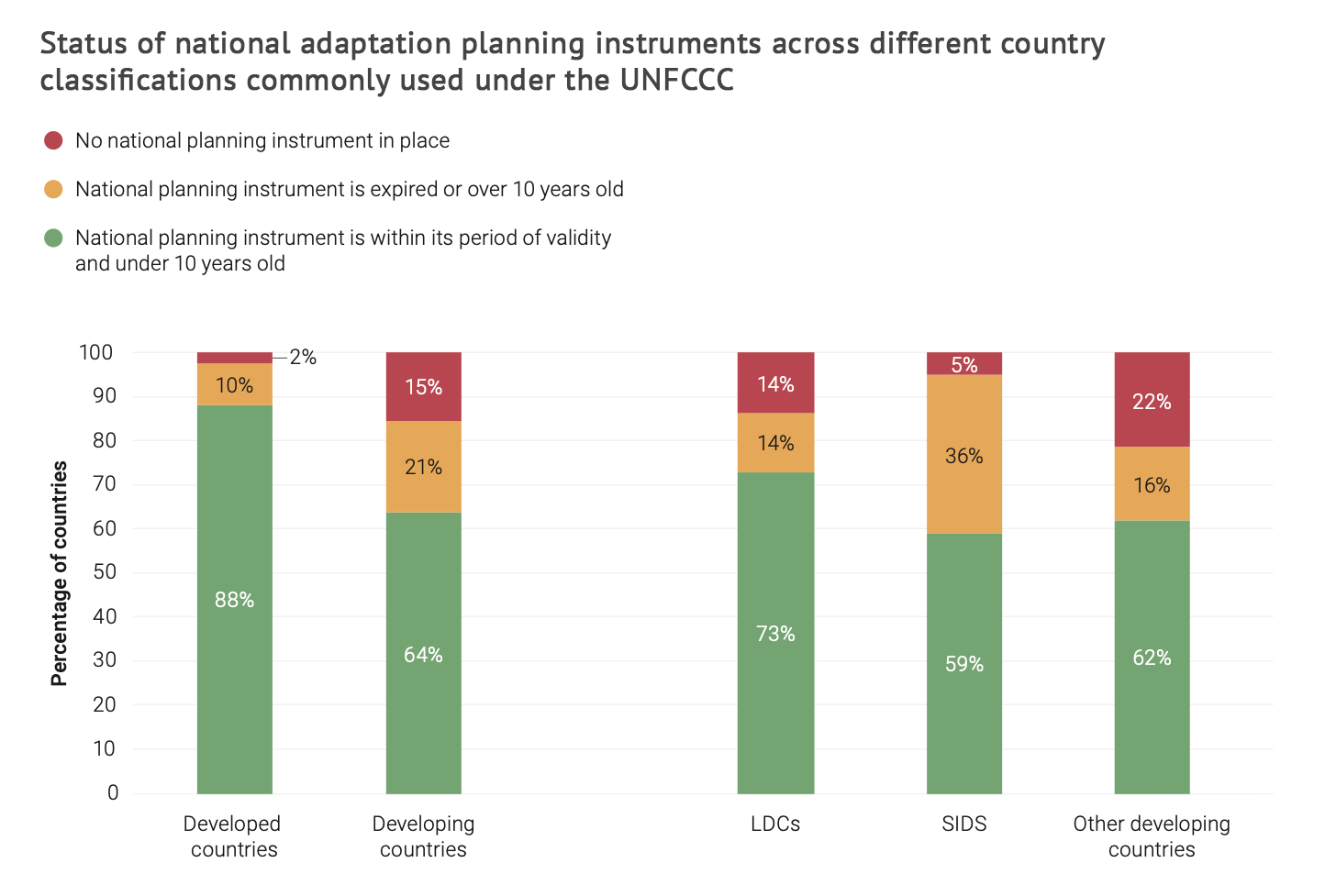

According to the report, 87% of countries had at least one national adaptation policy, strategy or plan in place as of 31 August 2025. However, 36 of these 172 countries’ plans are “expired” or “outdated”.

Meanwhile, 25 countries had no national adaptation plan at all, according to the report. It explains that these are “predominantly developing countries, suggesting that financial, technical and human resource constraints inhibit national adaptation planning”.

Of these countries without plans, 21 have “initiated a process to develop” a national adaptation plan, according to the report. However, it notes that many of these countries have “been in this process for a long time”.

The chart below shows the percentage of countries from different “country classifications” that have no national adaptation planning instrument in place (red), an expired adaptation planning instrument in place (yellow) and a valid instrument in place (green).

The report also discusses different types of adaptation “mainstreaming”. This is defined by the report authors as the “integration of adaptation objectives and climate risk considerations into the established functions, policy and practice of government institutions to build climate resilience”.

The authors list six different mainstreaming strategies. For example, “directed” mainstreaming means “dedicating funding, staff capacity-building and resources specifically to adaptation, including through financial frameworks and fiscal processes such as budget planning”.

Another example is “regulatory mainstreaming”, which means “modifying the formal or informal policy instruments such as legislation, frameworks, strategies and plans by integrating adaptation”.

According to the report, only regulatory mainstreaming is captured by the framework for the global goal on adaptation’s target related to planning.

The report also outlines the different “levels” of mainstreaming. These range from “prioritisation”, which it describes as a strong level of mainstreaming in which adaptation takes precedence over existing policy goals, to “coordination”, in which adaptation “is recognised as a policy goal, but is secondary to existing priorities”.

However, the report says there is “presently no agreement on how to measure and assess the outcomes of mainstreaming”.

Implementation of adaptation measures is progressing – but gaps remain

Under the UN “enhanced transparency framework”, countries are required to submit information about their climate progress in biennial transparency reports (BTR). The first report was due at the end of 2024.

The adaptation gap report calls BTRs the “most comprehensive national source of information on adaptation implementation worldwide available”.

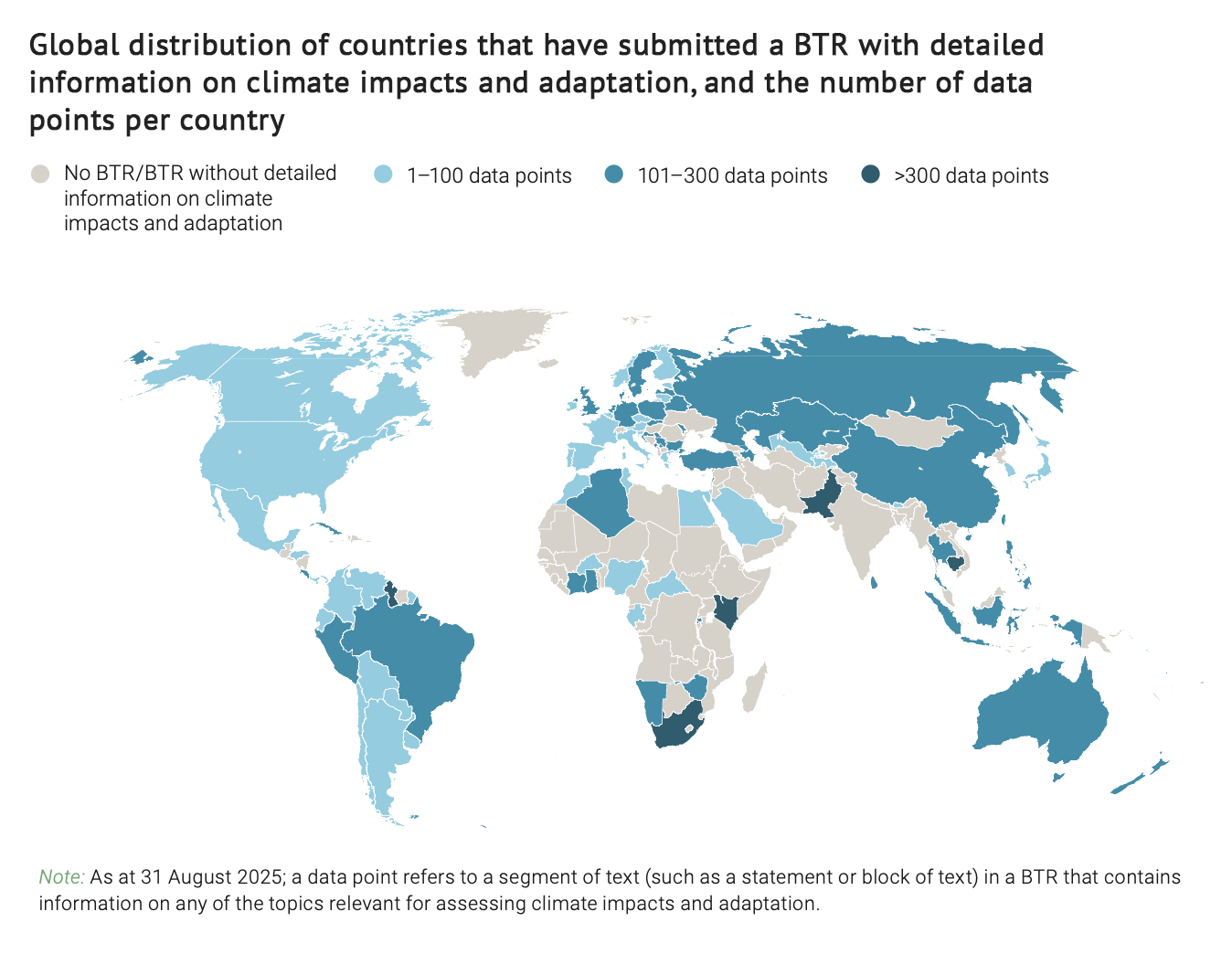

The report says that 105 countries had submitted BRTs as of 31 August 2025, of which 94 include details about adaptation

The authors find that 75 of these BTRs mention gender in relation to adaptation. However, only 4% of the results reported through BTRs are directly related to “gender and social inclusion”.

The report also highlights the “uneven coverage” of BTRs globally. According to the report, 88% of developed countries have submitted a BTR, compared to only 37% of developing countries.

It adds that there are further inequalities within the bracket of “developing countries”. Only 21% of SIDS and 14% of LDCs have submitted BTRs with “detailed information on climate impacts and adaptation”, according to the report.

This could “indicate that preparing national reports such as BTRs is most burdensome for the countries with the least capacity”, the report authors suggest.

The map below shows the countries that have submitted a BTR including “detailed information on climate impacts and adaptation” (blue) and those that have not (grey). For the former category, darker blue indicates that the country’s BTR includes more segments of text (data points) about climate impacts and adaptation.

The report finds that countries are “disproportionately reporting on climate hazards, systems at risk, climate change impacts and adaptation priorities” in BTRs. Meanwhile, only 15% and 7% of the data points in the map above discuss adaptation “actions” and “results” respectively.

In total, the report identifies 1,640 “adaptation actions” across 68 BTRs. It says that 23% of these are related to “biodiversity and ecosystems”, 18% to “infrastructure and human settlements”, 16% to “water and sanitation” and 14% to “food and agriculture”.

However, it finds that actions targeting health and poverty alleviation or livelihoods are each accounting for only 5%, while those addressing cultural heritage are “nearly absent” and account for less than 1% of all reported actions.

In a separate analysis, the report explores documents submitted by developing countries to the UNFCCC to understand how adaptation needs break down by sector. It finds that the 55 plans submitted by developing countries which include “detailed sectoral information” reveal that the agriculture and food sector and water supply are “common priorities across all regions, though they vary in terms of their relative importance”.

The NCQG is insufficient on its own to meet adaptation finance needs

At COP29 last year, developed nations pledged to raise at least $300bn per year under the NCQG for both mitigation and adaptation.

The report says that, although the target “appears significantly higher than the previous goal for developed countries to mobilise $100bn by 2020 for developing countries”, it is still “clearly insufficient” to meet adaptation finance needs in 2035.

The report sets out two reasons for this.

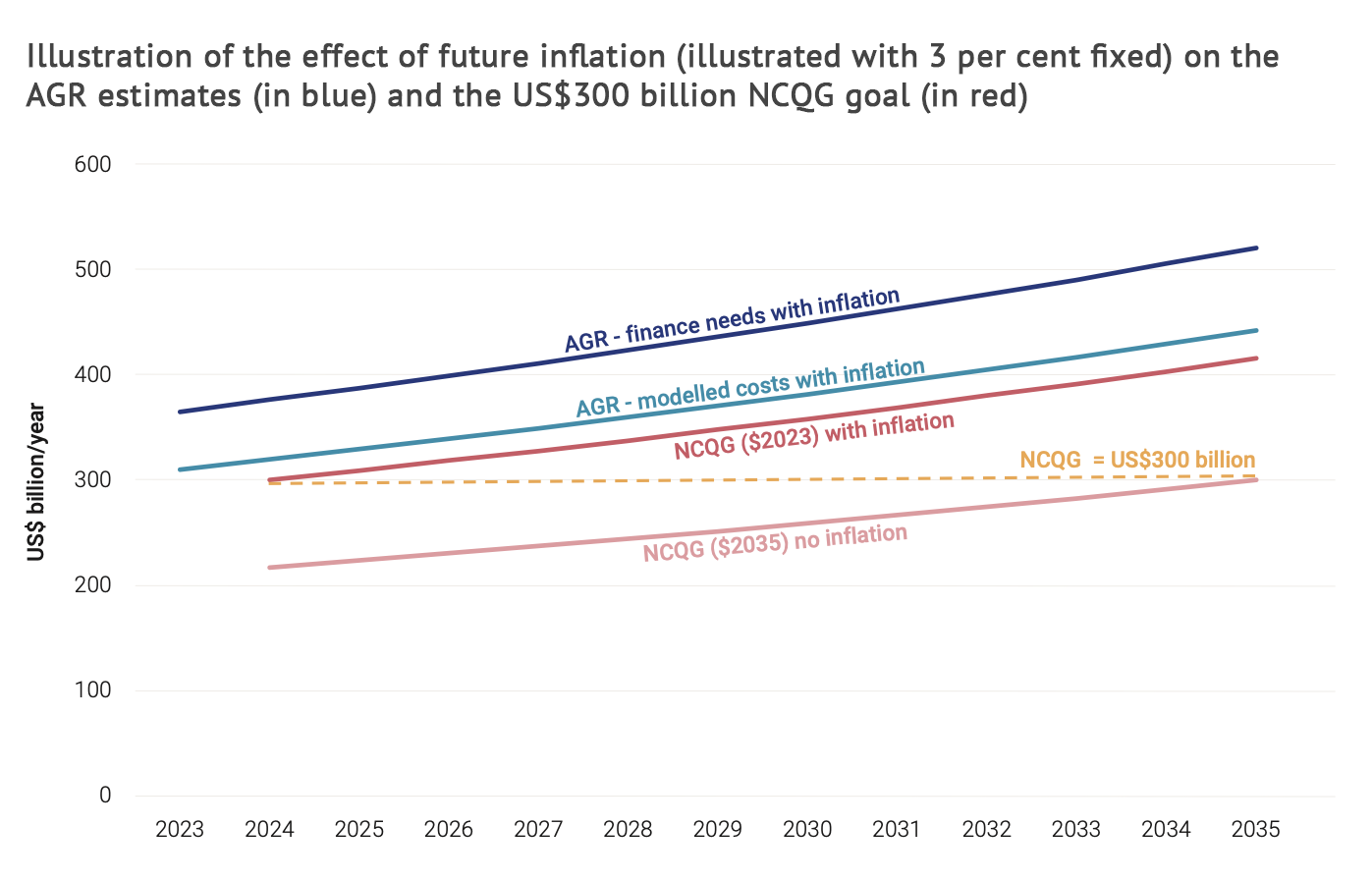

First, the authors explain that the $300bn target is not adjusted for inflation. It says that adaptation costs for developing countries are currently estimated at $310-365bn annually until 2035, based on costs in 2023. However, when adjusting for an inflation rate of 3% per year for the next decade, this number rises to US$440–520bn by 2035.

(In an analysis published last year, Carbon Brief noted that the $300bn target does not account for inflation.)

The plot below shows the effect of inflation on adaptation finance needs (dark blue) and modelled costs (light blue). It also shows the NCQG goal, accounting for inflation, based on 2023 costs (red) and without inflation based on 2035 costs (pink). It also shows the NCQG goal of $300bn by 2035 (yellow).

Second, it notes that the NCQG covers both mitigation – namely, efforts to cut emissions – and adaptation. So far, it warns that no “subgoal” has been agreed to determine how much money goes to each.

The report authors have also developed two scenarios exploring how much the NCQG would bridge the adaptation finance gap, if the $300bn target is met, both of which account for inflation. These are:

- A “minimum adaptation scenario”. The authors assume that 26% of the NCQG money will be used for adaptation finance as this is the percentage of all international climate finance that was spent on adaptation over 2011-20. Based on historical proportioning of finance, $3bn of the resulting $78bn this would go to SIDS and the rest to $25bn to LDCs.

- A “maximum adaptation scenario”. Under this scenario, the Glasgow Pact and Baku to Belém Roadmap are achieved, meaning that adaptation funding reaches $40bn annually by 2025 and $120bn annually by 2030. They also assume that adaptation finance grows by 7% per year, reaching $166bn by 2035 – more than half of the NCGQ finance goal of $300bn. Under this scenario, SIDS would receive $6bn in adaptation funding by 2035 and LDCs would receive $55bn.

The report concludes that, even if the NCQG is achieved, a “significant adaptation finance gap” is likely to remain in 2035 “regardless of the share of international public climate finance that will flow towards adaptation”.

Meanwhile, the report notes that private-sector finance can help “fill the adaptation finance gap” – but cautions that its overall contribution is likely to be “modest”.

The “realistic” potential for private-sector investment, according to the report, is $50bn per year by 2035 – a figure it estimates would cover 15-20% of overall estimated needs.

Reaching this level of private-sector finance will require “targeted policy action” given that current private-sector flows to “publicly identified” adaptation priorities in 2023 are estimated at $5bn, it notes.

Furthermore, UNEP warns that many proposed approaches for raising private-sector funds for adaptation measures pass “most of the costs of adaptation back to developing countries or households”.

The post UN report: Five charts which explain the ‘gap’ in finance for climate adaptation appeared first on Carbon Brief.

UN report: Five charts which explain the ‘gap’ in finance for climate adaptation

Climate Change

Bridging Knowledge Systems: Indigenous Nations and Academia Collaborate on Climate Research in Canada

On the tundra in Inuit Nunangat, an Elder kneels by thinning sea ice, pointing to the cracks forming earlier each spring. Nearby, community youth work with researchers to set up monitoring equipment that tracks ice thickness, temperature shifts, and permafrost thaw. Together, they are documenting climate change not from separate vantage points, but in conversation, where Inuit knowledge of the land and Western science meet.

Across Canada, such collaborations are on the rise. Indigenous Nations and academic institutions are joining forces to confront climate change, weaving together Indigenous ways of knowing with scientific methods. These partnerships hold immense promise: they deepen understanding, inform adaptation strategies, and strengthen resilience for both Indigenous and non-Indigenous communities. But they also raise urgent questions about ethics, ownership, and how to move beyond colonial legacies that have historically extracted and exploited Indigenous knowledge.

The Promise and Pitfalls of Collaboration

When done respectfully, Indigenous–academic partnerships generate knowledge that neither system could produce alone. Indigenous expertise, rooted in millennia of relationship with land, water, and sky, offers insights into biodiversity, ecosystem health, and patterns of climate change that Western science is only beginning to measure. Meanwhile, academic research provides tools like data modelling, satellite mapping, and policy advocacy that can elevate Indigenous voices in national and global decision-making spaces.

Yet the pitfalls are significant. Indigenous intellectual property (IP), the stories, practices, symbols, and innovations that belong to Indigenous Peoples, has too often been taken without consent, acknowledgment, or benefit. In Canadian history, knowledge of plants, medicines, and land-use practices has been extracted and patented, leaving communities with nothing but loss and mistrust. These harms are not distant memories; they shape the caution and hesitation many Indigenous Nations feel when approached by universities today.

For Indigenous communities, protecting IP is not only about legal safeguards. It is about sovereignty: the right to control how knowledge is shared, by whom, and for whose benefit. Without this, collaboration risks reproducing the very colonial patterns it claims to resist.

Academia’s Growing Commitment to Ethical Partnerships

Thankfully, many Canadian academic institutions are beginning to come to terms with this history and adopt new approaches to research. Universities are developing frameworks and policies that embed principles of respect and accountability, such as:

- Free, Prior, and Informed Consent (FPIC): Research can only proceed with the voluntary and fully informed agreement of Indigenous Nations.

- Respect for Indigenous data sovereignty: Communities must control how data is stored, accessed, and used.

- Co-creation of research questions and methods: Projects must be shaped together, not imposed by academics.

- Equitable sharing of benefits and authorship: Indigenous collaborators must be credited and compensated fairly.

- Long-term accountability: Partnerships should outlast funding cycles and continue to serve community priorities.

This shift is not perfect, nor is it complete. But the trajectory is encouraging: Indigenous governance and ethics are increasingly central to climate research in Canada.

Consequences of Collaboration: Good and Bad

The outcomes of these partnerships are not abstract. They have real consequences for climate action on the ground. Where research has gone wrong, communities recall sacred sites being surveyed without consent, knowledge of medicinal plants being patented for corporate use, and environmental studies that used Indigenous stories but excluded Indigenous voices from authorship. These failures reinforce mistrust and make communities wary of outsiders.

By contrast, when done well, collaboration strengthens both knowledge and resilience. For example:

- The Kainai Nation and the University of Calgary collaborate on drought adaptation, combining climate modelling with traditional food system knowledge to develop locally grounded strategies.

- The Tłı̨chǫ Government and Carleton University are monitoring permafrost thaw in the Northwest Territories, where Indigenous knowledge guides interpretation while scientific tools quantify the scale of change.

- The Anishinabek Nation and Lakehead University collaborate to restore wild rice beds, combining ecological monitoring with stewardship practices that sustain both ecosystems and culture.

These projects illustrate what is possible when Indigenous leadership is respected and academic expertise is aligned with community priorities.

Youth, Future Generations, and the Global Context

Collaboration is not only about research results, but also about building capacity for future generations. Training Indigenous youth in both traditional and scientific methods ensures continuity of stewardship and opens pathways into climate sciences, data analysis, engineering, and policy. This intergenerational transfer is critical, as it is young people who will live most directly with the consequences of climate change.

Canada is not alone in this work. Around the world, Indigenous communities are leading partnerships with academia. Māori researchers in Aotearoa, New Zealand, develop coastal restoration strategies grounded in whakapapa (genealogy), and Sámi leaders in Scandinavia combine herding knowledge with climate models to track changes in snow and migration patterns.

Canada has an opportunity and a responsibility to lead globally by embedding Indigenous governance within research institutions and climate policy.

What Indigenous Communities Should Consider

When invited into research collaborations, Indigenous Nations should feel empowered to set terms, ask questions, and safeguard their knowledge. Key considerations include:

- Consent: Has Free, Prior, and Informed Consent been obtained, clearly and respectfully?

- Intellectual Property: Who owns the data and knowledge? How will it be used, stored, and protected?

- Community Benefit: Does this project address our priorities and bring tangible benefits to our people?

- Co-creation: Were we part of shaping the questions and methods, or are we being slotted into a pre-existing framework?

- Cultural Protocol: Are researchers prepared to follow our laws, ceremonies, and privacy requirements?

- Data Sovereignty: Will data remain under our governance?

- Capacity Building: Will this train our youth, employ our people, or build local expertise?

- Publication Rights: Do we have control over how findings are published, and will our members be acknowledged as co-authors?

- Exit Plan: What happens when the project ends? Will knowledge, data, and benefits remain with us?

These questions are not barriers; they are safeguards to ensure collaboration is ethical, reciprocal, and grounded in Indigenous sovereignty.

Strengthening Indigenous–Academic Partnerships

To move forward, Canada must think beyond project-by-project partnerships and build systemic change built in true collaboration with Indigenous-led initiatives such as:

- Embedding Indigenous governance in research ethics boards.

- Supporting Indigenous-led research universities and centres of excellence.

- Creating funding streams that prioritize Indigenous research sovereignty.

- Establishing national policy frameworks to protect Indigenous knowledge.

- Formalizing spaces for reciprocal knowledge exchange that place Indigenous and Western knowledge systems on equal footing.

These steps shift collaboration from a transactional to a transformational approach.

A Call to Action

The convergence of Indigenous knowledge and academic research offers immense promise in confronting climate change. Together, these systems can generate insights grounded in centuries of relational stewardship and sharpened by scientific rigour. But true collaboration demands more than goodwill. It requires dismantling colonial patterns, affirming Indigenous intellectual sovereignty, and ensuring that research benefits the lands and peoples from which it arises.

To academia: move beyond consultation and share governance of research with Indigenous Nations.

To governments: fund Indigenous-led research and respect Indigenous sovereignty in climate policy.

To Indigenous Nations: know your power, set the terms, protect your knowledge, and demand reciprocity.

The path forward shines brightest when Indigenous and academic knowledge systems walk side by side. If Canada adopts this model, the future will not only be more just, but also more resilient for the land, the waters, and future generations.

Blog by Rye Karonhiowanen Barberstock

Image Credit : Julian Gentile, Unsplash

The post Bridging Knowledge Systems: Indigenous Nations and Academia Collaborate on Climate Research in Canada appeared first on Indigenous Climate Hub.

Climate Change

“New era of climate extremes” as global warming fuels devastating impacts in 2025

In 2025, greenhouse gas emissions produced by human activities turned what should have been a cooler year into one of the hottest ever, fuelling more dangerous and frequent heatwaves, droughts, storms and wildfires, climate scientists said in an annual report.

Planet-heating emissions primarily caused by burning fossil fuels pushed temperatures this year to “extremely high” levels, worsening extreme weather with devastating consequences – especially for the world’s most vulnerable, concluded scientists working with the World Weather Attribution (WWA) group.

Despite the return of La Niña – a climate pattern linked to large-scale cooling of the Pacific Ocean, which can temporarily bring milder global temperatures – the EU monitoring service Copernicus has said 2025 is “virtually certain” to end as the second- or third-warmest year on record.

In its report released on Tuesday, the WWA research group found that climate change made 17 of the 22 extreme weather events it assessed this year more severe or more likely, while its remaining studies were inconclusive, mostly due to a lack of weather data from remote areas.

Ranging from heatwaves in South Sudan and Western Europe to extreme rainfall in Southeast Asia and wildfires in Los Angeles, those disasters killed thousands of people and displaced millions from their homes.

11 extra hot days since Paris Agreement

Theodore Keeping, a researcher at Imperial College London, said the catastrophic wildfires, record-breaking rainfall, unprecedented temperatures and devastating hurricanes seen in the last 12 months provide “undeniable evidence” of a rapidly changing global environment.

“We are living in the climate that scientists warned about a decade ago, when the Paris Agreement was signed,” he added.

Since the landmark accord was adopted in 2015, global average temperatures have risen by about 0.3C, and the world now experiences an average of 11 additional hot days each year, according to WWA’s research.

For the first time, global average temperatures over the last three years are on track to exceed 1.5C, the most ambitious goal governments agreed in Paris, according to the EU’s Copernicus service. The UK’s Met Office expects 2026 to be between 1.34C and 1.58C hotter than preindustrial levels.

“The continuous rise in greenhouse gas emissions has pushed our climate into a new, more extreme state, where even small increases in global temperatures now trigger disproportionately severe impacts,” said Sjoukje Philip, a researcher at the Royal Netherlands Meteorological Institute (KNMI). “We are entering a new era of climate extremes, where what was once an anomaly is quickly becoming the norm,” she added.

Silent-killer heatwaves

While heatwaves don’t leave a visible trail of destruction and often go underreported, the research group found they were the deadliest extreme weather event of 2025. One study estimated that climate change more than tripled the number of deaths caused by searing temperatures recorded across Europe this summer.

In South Sudan, extreme heat forced schools to close for two weeks in February 2025 after dozens of children collapsed with heatstroke. Human-made climate change made that heatwave 4C hotter and transformed an exceptionally rare event into a common one, now expected to happen every other year in South Sudan, a WWA assessment found.

Keeping of Imperial said the impacts are disproportionately shouldered by women and girls who predominantly work in sectors with high heat exposure such as agriculture and street-vending.

Flood risks rise as adaptation limits near

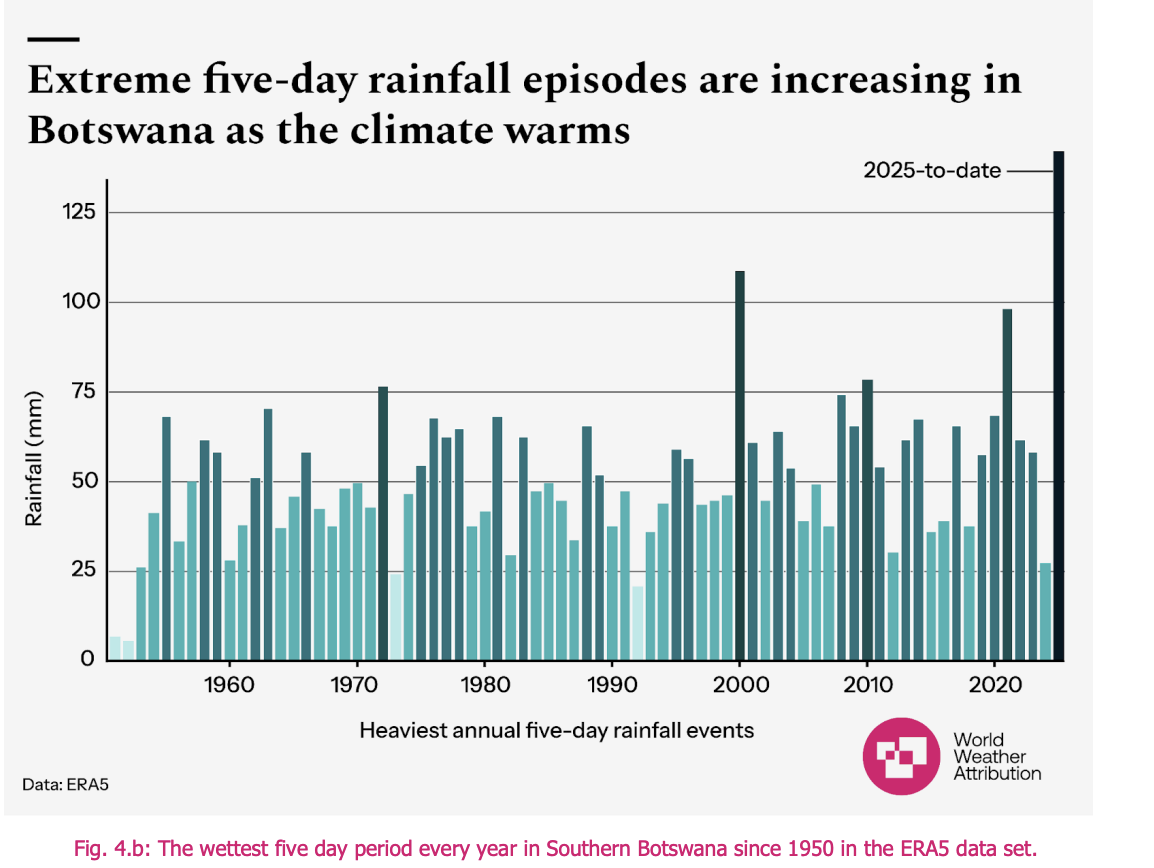

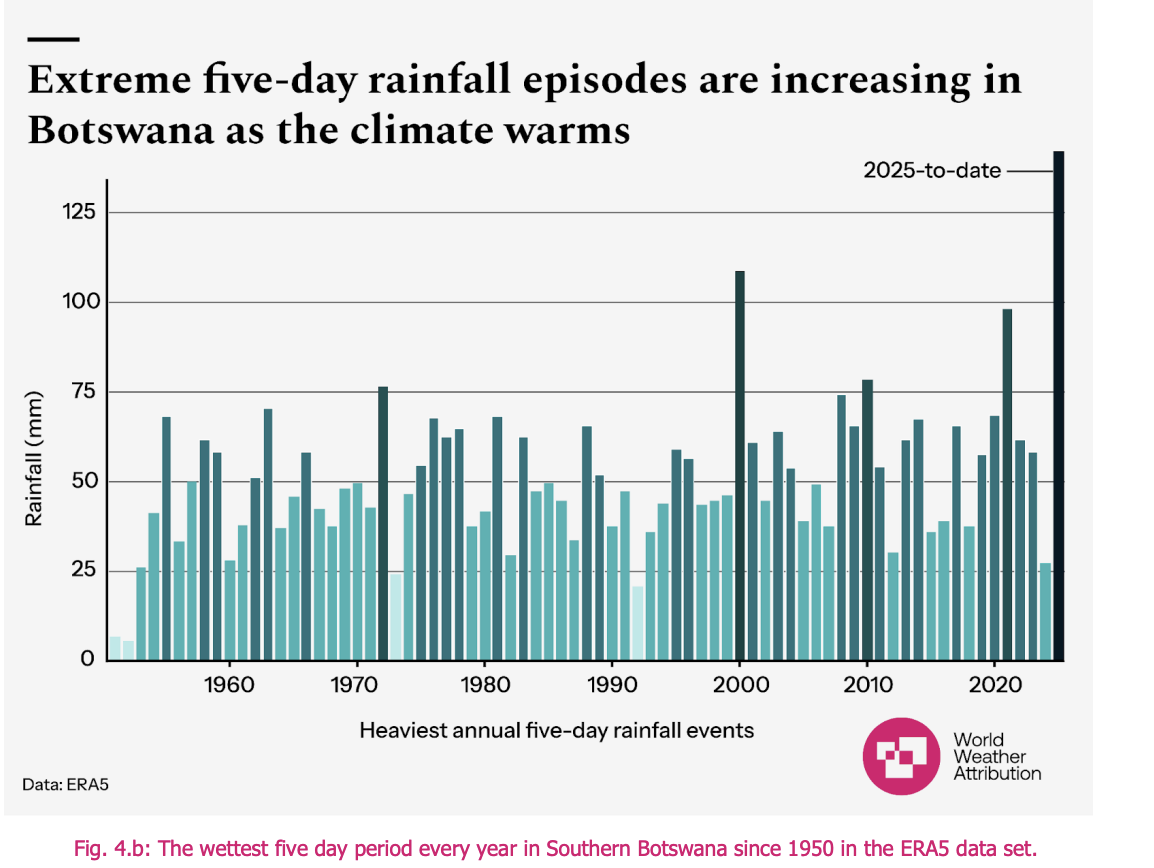

Floods were the disasters most studied by the WWA team in 2025, with devastating downpours made worse by climate change hitting Pakistan, Sri Lanka and Indonesia, the Mississippi River Valley in the US and Botswana.

In the Southern African nation, spells of extreme rainfall are becoming more frequent within a single year, while the rapid expansion of urban centres without adequate infrastructure upgrades makes them more susceptible to severe flooding, according to WWA.

The research group said this underscores the urgency of investing in measures to adapt to a warming world which can prevent many deaths and widespread destruction but remain critically underfunded.

However, the scientists also warned that even strong efforts to prepare for disasters cannot prevent all impacts, as climate change is already pushing millions close to the “limits of adaptation”.

“Jamaica was in a state of preparedness for Hurricane Melissa five days before landfall,” noted Keeping, “but when such an intense storm hits a small island nation in the Caribbean, even high levels of preparedness cannot prevent extreme losses and damages”.

Fossil fuel dependency is “costing lives”

Hurricane Melissa caused an estimated $8.8 billion in physical damage in Jamaica, equal to 41% of the country’s 2024 GDP, with only a small share of the losses expected to be covered by innovative insurance schemes.

In their report, WWA researchers said that drastically reducing fossil fuel emissions remains the key policy to prevent the worst climate impacts.

“Decision-makers must face the reality that their continued reliance on fossil fuels is costing lives, billions in economic losses, and causing irreversible damage to communities worldwide,” said Friederike Otto, WWA’s co-founder.

The post “New era of climate extremes” as global warming fuels devastating impacts in 2025 appeared first on Climate Home News.

“New era of climate extremes” as global warming fuels devastating impacts in 2025

Climate Change

Nonprofit Center Works with Rural Maine Towns to Prepare for and Protect Against Extreme Weather

Weather disasters are shared experiences in the Maine foothills and communities are preparing for a wetter, warmer future.

The December 2023 flood. The 2022 Halloween storm. The Patriots Day storm of 2007. The Great Ice Storm of 1998.

Nonprofit Center Works with Rural Maine Towns to Prepare for and Protect Against Extreme Weather

-

Climate Change5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Renewable Energy6 months ago

US Grid Strain, Possible Allete Sale