Rachel Kyte CMG was appointed the UK’s special representative for climate in October 2024.

She is professor of practice in climate policy at the University of Oxford’s Blavatnik School of Government, as well as dean emerita at Tufts University’s Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy.

Previously, Kyte was the UN secretary-general’s special representative for sustainable energy, the CEO of Sustainable Energy for All and a vice president and special envoy for climate change at the World Bank.

- On her priorities for the role: “It’s really finance, forests and the energy transition externally.”

- On fraught geopolitics: “The Paris Agreement has worked; it just hasn’t worked well enough.”

- On the Paris Agreement: “It’s better than anything else we could negotiate today.”

- On the global response to Trump: “The rest of the world is like, ‘we’re growing, we need to grow, the fastest energy is renewable, how do we get our hands on it?’”

- On keeping 1.5C “alive”: “1.5C is still alive. 1.5C is not in good health.”

- On net-zero: “[T]he whole concept of net-zero is under attack from different political factions in a number of different countries. It is not isolated to one or two countries.”

- On climate pledges from key countries: “Let’s not make a fetish out of under-promising.”

- On delivering these pledges: “The conversations that I am engaged in…are like: ‘There’s no question about the direction of travel. The question is about the pace at which it can be executed.’”

- On COP30 outcomes: “The UK is engaged extensively with Brazil on a…potential large nature-finance package.”

- On climate impacts: “[W]e’ve got to deal with issues of adaptation, because [climate change is] happening right now, right here, right everywhere.”

- On fossil-fuel phaseout: “I think there are lots of informal discussions…around [whether] there [is] something [that] can be done on fossil-fuel subsidies.”

- On the climate-finance gap: “The pressure on our public resources is to make sure that that is targeted at where it can have the most impact.”

- On being an “activist shareholder”: “[T]he UK, which is such a significant shareholder across the multilateral development bank system…we have to be an activist shareholder.”

- On COP reform: “Should there be…summits every two years? People are talking about that.”

- On finance and the global south: “I’m not Pollyanna about this, but people [have] got really big problems in front of them.”

- On calls to slow action: “[W]hat I think we’re very forceful about is that you can’t take two to three years out of climate conferences just because the world’s really difficult.”

- On the impact of US tariffs: “[T]he sort of tariff era we’re in, the risk is that it slows down the investment in the clean-energy transition at a time when it needs to speed up.”

- On China’s role in the absence of the US: “They already were a major player. The world had already shifted in that direction.”

- On her climate “epiphany”: “I remember some very, very, strange meeting somewhere in eastern Europe and watching a really badly made movie about migration.”

Listen to this interview:

Carbon Brief: You were appointed the UK special representative for climate last October, a role that’s been held by the likes of John Ashton, David King and Nick Bridge over the last 15 years or so, and was left unfilled towards the tailend of the last government. Please, can you just explain what the role is and what your priorities are for it?

Rachel Kyte: So, it’s good to talk to you, nice to be here. So, the Labour government decided to appoint two envoys. They are politically appointed, so that does distinguish it a little bit from the past and so we are not civil servants; we occupy this space in support of ministers and in support of the civil service. So I’m the climate envoy and Ruth Davis is the nature envoy. I report to the foreign secretary [David Lammy] and the secretary of state for net-zero [Ed Miliband], and Ruth reports to the foreign secretary and to the secretary for Defra [Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs] [Steven Reed].

And our role is to help ministers project British climate and nature priorities in our engagements in the world. So we are externally focused, outside of the UK, and I think that Ruth and I coming in, and in discussion with ministers in the first weeks that we were here, focused in on the energy transition internationally, which is the extension of the energy mission domestically. Really progress around forest protection [and] tropical forest protection, because this is obviously on the critical path to getting to net-zero and, with COP30 coming up, and, having COP in the forest, this seemed to be an urgent policy. And then, for me, finance. And, of course, there’s climate finance, which is what gets negotiated in the COPs. And then there’s the financing of climate, which engages in a wider cross-Whitehall conversation around how we are building [the City of] London as the green financial centre [and] how we are exploiting the fact that the green economy is growing faster than the economy [overall].

So, inward trade investment, but outward trade investment. How we are mobilising private-sector finance. So, it’s really finance, forests and the energy transition externally.

You can imagine that the foreign secretary has a world that has got an awful lot more complicated in recent years. We’ve got more wars than we’ve had. We’ve got more grade-four famines. It’s a very, very complicated world.

So I think the envoys are there to try to support the prioritisation of climate and nature at the heart of foreign policy, which is what [the foreign secretary] said in his Kew speech. But then helping the service of the [Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office] deliver that externally.

CB: Thanks, Rachel. You nicely segued into our next question. We can definitely all agree that geopolitics is pretty fraught at the moment, perhaps more so than any time for decades. Multilateralism is under extreme pressure. We’ve seen that through recent UN summits, not just the COP. How does international climate policymaking – and, in particular, the Paris Agreement – survive this period of turbulence in your view? And, from some actors, there’s obviously outright hostility coming from some angles.

RK: So, it’s a great question. At the core of all of that is the fact that the Paris Agreement has worked; it just hasn’t worked well enough. And so how do we keep the conceit of the Paris Agreement? Which is that countries would have their nationally determined contributions, and that that ambition would filter up, and then when you put a wrap around it, you’ve got something that is on a line to net-zero by the middle of the century.

If countries start to slow down, or if countries start to walk away from that, how does the Paris Agreement still live? And we’re in that moment now.

But I think we have to hold two truths in our minds at the same time [within] a lot of climate, energy, nature policy. So, on the one hand, there is a direct attack; the United States has decided to leave the Paris Agreement. And I think there are many other countries looking for clarity from the United States about whether it will leave the underlying convention [the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change] as well. We don’t know.

But when I travel around the world, not withstanding that and notwithstanding some of the transactional interactions of the United States with other countries on a whole range of issues, the rest of the world is like, “well, we need to grow, we need to grow fast, we need fast energy, in particular”, right? Because I think countries really are worried that if they can’t get the energy security that they need that it becomes difficult for them to manage their economies and meet their people’s needs, but they’re also very worried about missing out on the AI [artificial intelligence] revolution.

So everybody wants a data centre, everybody wants to have enough energy for AI. But I think many emerging markets and developing economies are really worried that if they miss this next S-curve this would be defining for them for the next step. So the rest of the world is like, “we’re growing, we need to grow green, the fastest energy is renewable, how do we get our hands on it?”

At the same time, obviously, we still haven’t peaked emissions from fossil fuels. There’s a short-term economy, which is alive and well and funding into gas, etc. And we have two world views about what the future of the energy transition is. We have a US view, which is that climate change…what seems to be being articulated now is “climate change is real, but it’s just not a priority for us right now and we’re doubling down on the fossil-fuel economy”.

And then kind of the rest of the world, which is, like, “yeah, we are in transition, maybe we need to slow the transition, because the world is insecure and unstable”, but, at the end of the day, they can only meet their goals with access to more clean energy.

So I’ve reduced it down to energy, but you can have that conversation on a number of other aspects. So, yes, we have to keep the Paris Agreement as the place where we move forward from. It’s better than anything else we could negotiate today. And I think that it, therefore, does need to transform itself a little bit into a way of moving implementation forward and to move outside of the confines.

So, for example, we discuss resilience in the global economy, we discuss resilience in conflict, and we discuss resilience in development and, in climate, we talk about adaptation finance. Those two things have different origins, but they are, at the end of the day, going to come together in the same sets of decisions that countries make. So, how do we move forward in that debate?

And then, in particular, for those countries that come to COPs every year and don’t get what they want and face the existential crisis, how does this continue to be meaningful for them? And I think we have to answer that question over the next couple of years.

CB: You mentioned the Paris Agreement. We’re almost 10 years on from that landmark moment. One of the central calls at that moment 10 years ago [was] “1.5C to stay alive”. Is 1.5C alive still?

RK: 1.5C is still alive. 1.5C is not in good health. And so there is an important moment that, between now and COP30 [in Brazil this November], and then coming out of COP30, we will receive the synthesis report from the UN based on all of the NDCs [nationally determined contributions]. And we will get a sense of what kind of critical condition 1.5C is in.

And then I think we have to, as an international community, work out how to address that, but also how to communicate that to the world’s publics. Because, obviously, the whole concept of net-zero is under attack from different political factions in a number of different countries. It is not isolated to one or two countries.

So, I think the question of how we communicate where we are in the transition, it has to be addressed once we see the synthesis report. But that also goes to what’s really important for the next few weeks for me and the British government, which is to still encourage those countries that have to file their NDCs to have NDCs which are stretch targets; realistic, but ambitious.

We’ve still got the EU to come in. Still got China to come in. There are a number of key economies that haven’t filed their NDCs yet, so we can sort of get very doom-laden about where we are, but there is an opportunity for a number of key blocs to still maintain the ability to be ambitious.

CB: What are you particularly looking for from, say, the EU or China, some of these key NDCs?

RK: Well, to not walk away from ambition. There are all kinds of factors that go into a country’s NDCs; the capability, the rates of economic growth, the politics and the different political cultures have a different approach to under-promising and over-delivering, versus over-promising and under-delivering.

And, while you can respect under-promising and over-delivering, the delivery is important at this particular moment with [the] Paris [Agreement] fragile. I would say that this is the moment to promise realistically, right? And I think that’s where British diplomacy is focused at the moment. Let’s not make a fetish out of under-promising.

CB: Do you think that message is landing?

RK: Yeah, I think people are…So, my impression is that no country in the world is not living in the world, right? So people are watching the tariff wars, but…this is complicated. What does this mean for us?

I was in Southeast Asia a few weeks ago. Every country is trying to get a deal with the US and understand whether things are stable, or whether they’re going to change. It has direct impacts on the flow of finance into the clean-energy infrastructure that needs to be built. It has a direct impact on the cost of capital, etc.

Every country is watching the broader geopolitics. Everybody’s watching people become distracted by other wars and conflicts. And, in the middle of that, you’ve got to plot your way through to growth, right? And then that growth has to be greener, because [of] the cost of clean air or the benefit of clean air, the benefit of jobs, etc. This is understood, but this is a particularly difficult environment in which to navigate.

And, in the middle of that, we’re asking countries to plot out how they’re going to get to where they are committed to being. And for countries that produce conditional NDCs – ie if the finance is there, then we can do this – both trade and finance and international cooperation have been disrupted over the last year.

So, NDCs are complicated things to produce at the moment, just like any other growth plan. And so the conversations that I am engaged in, the further east and south you go, are like: “There’s no question about the direction of travel. The question is about the pace at which it can be executed.”

CB: Looking ahead to COP30 in Brazil later this year, realistically, you’ve already talked about a lot of different tensions that we’re facing, So what kind of outcomes are you expecting? And what are you pushing for?

RK: The UK is engaged extensively with Brazil on a couple of things. One is, I would describe it as a potential large nature finance package, right? Carbon markets, we agreed Article 6. There’s technical work that’s going on. There’s a lot of Article 6.2 activity. We are leading the coalition with Singapore and Kenya on demand for voluntary carbon markets. The Brazilians are very interested in the interoperability of compliance markets. So a piece around really driving carbon markets forward, because that would be a new stream of revenue, much needed, right? And answers part of the climate-finance problems.

Secondly, is the TFFF, the tropical forest – I always get it wrong –Tropical Forest Forever Facility. This is a flagship initiative of the Brazilian government and, if we have a COP in the forest, then we should be able to make breakthroughs in how we address the need to have a flow of finance into tropical-forest countries.

So, we’re working extensively with the Brazilians and we’re waiting for them to come forward with the prospectus. And then the question is our contribution [to the TFFF], if we make one with others, and also our ability to help the Brazilians go, basically, on a road show, right? And get other private-asset owners and asset managers and others into this fund.

And then maybe other nature finance things to do. Remember that biodiversity COPs always talk about climate, climate COPs never talk about nature, so we can correct for that. So that would be one bucket.

Then there’s going to be, this will not be negotiated, but the Brazilians will produce, together with the Azerbaijanis, a Baku-to-Belém roadmap. This, hopefully, will demystify how we get from $300bn to $1.3tn, or whatever the number is, and start to talk about how we scale; the leverage of public money for private money. So this is issues of standardisation of different asset classes, new asset classes [and] new ways of issuing bonds. So all of the mechanics of international finance that can be mobilised. And I think this is not well understood in a COP. It might be well understood in the City [of London] or in Frankfurt or Wall Street, but maybe this roadmap can demystify it.

And then I think we’ve got to deal with issues of adaptation, because it’s happening right now, right here, right everywhere, and the questions of adaptation finance, which isn’t just about the “quantum”. It’s also about what kind of financing: the grants, the need for concessional [financing], where the private sector is really able to mobilise and also quality [finance], and it’s also the accessibility of that finance.

We’re seeing huge improvement in the performance of the Green Climate Fund. The multilateral climate funds are just emerging now into an era where they can start to really deliver at scale. And then we’ve got the reform of the MDBs [multilateral development banks], where we, I think, have to be a much more activist shareholder.

So, finance, forests, bigger package on nature. I mean, there’s a lot more that needs to be negotiated, but I think those would be things that we can do, not withstanding the geopolitics.

CB: I’m quite struck that almost all of those things that you talked about are outside of the formal [COP30] negotiations. What do you think is going to happen on something like carrying forward the fossil-fuel transition outcome from Dubai?

RK: So I think there’s two things going on, right? One is what can we negotiate in the current environment, with the current postures of different groupings and different countries, and getting moving on the action around tripling renewables, doubling efficiency and transitioning away [from fossil fuels] is very important.

So, what could that look like? I think there are lots of informal discussions at the moment between different groups and with the Brazilians around [whether] there [is] something [that] can be done on fossil-fuel subsidies? Can we set targets within that that would allow us to measure progress? What can we usefully agree on that, this year?

And, then, I think there [are] conversations around where does the stuff that’s happening outside of COP land in a negotiated text? Or how does it get referenced?

I think we’re waiting for clarity from the Brazilians about their approach to a “cover text” and things like this. And I think this is still in the air. But these things that could happen outside of the negotiated text, referenced appropriately, give life and meaning to some of the paragraphs that need to be negotiated.

CB: With many major donors, including the UK, cutting their own budgets, even as countries made this collective pledge to scale up climate finance that you referenced, there’s a lot of expectation now on institutions like the World Bank and the multilateral development banks. Are these institutions capable of filling this climate-finance gap? Or where else should developing countries be looking? You mentioned maybe some of the carbon-market kind of revenue-raising, potentially? But, just on the wider pressures they are now facing, as we already alluded to, the kind of pressure on those multilateral institutions…

RK: Yes. So, we’re now basically – across the OECD [Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development] – with a lot of countries hovering at like 0.3% GDP for ODA [official development assistance]. So, first of all, the war on nature and the climate crisis are one and the same thing, [they] are the context within which all growth and development happens, right? So the pressure on our public resources is to make sure that that is targeted at where it can have the most impact, where it’s needed most, and targeted at where it can be, where it can leverage itself, right?

So, we can talk about how we use ODA to sort of reduce emissions. There are certain geographies where emissions need to be curbed in order for us to get to 1.5C and then how do we use the public money to leverage other resources to crowd in and end the destruction of tropical rainforest or the protection of mangroves. So you take your climate-critical path, and you look at your ODA and you say: “How do we apply this the most effectively?”

For a country like the UK, which is such a significant shareholder across the multilateral development bank system, then we have to be an activist shareholder. And, yes, the answer is that the MDBs could do more. First of all, they’re doing more now than they were a few years ago. And they could do even more.

If we look at the leverage rates of the MDBs, those could go up. And I think in the conversations around the $300bn at COP29 it was very clear, especially from the regional development banks, that they thought that they could do more. And I think that in some instruments and in some ways in which they work, they could do a lot more. So I think those leverage rates should be over $1 for certain facilities, etc.

We know a lot more about how to use guarantees. We know a lot more about how to leverage the private sector using MDBs. The classic example for us was taking the Climate Investment Funds (CIF), putting a bond structure around their performing portfolio, and then listing it in London [on the stock exchange] and raising $7bn [$500m, following clarification after the interview], which then goes back to the CIF to be reinvested. I think there’s just been recent stories about the Inter-American Development Bank [IADB], which has a set of performing assets in its portfolio of renewable energy that can be turned into an instrument that can be listed, that generates money, that goes back into IADB.

So I think this is learnt now and, because of the ODA cuts, this becomes very, very important. So I am confident that there is a “to-do list” and that to-do list has come out of MDB reform work. It’s come out of the G20, TF-CLIMA, it’s come out of the Brazilians last year. It’s come out of other work that other thinktanks and others have been doing. London just listed…the government just announced a sustainable debt work here in the UK. So, that to-do list is a kind of “known known”. Right now the question is implementing it and that will require political leadership, for sure. And the Brazilians have created a circle of climate ministers, sort of 30 climate ministers to lead that. And there is a coalition of finance ministers convened by the World Bank.

We know what we need to do and now we need to start working out how to do it. The other thing is that we have an investor taskforce that the Treasury and the Foreign Office and leaders from the private sector have set up. And that’s sort of crunching its way through the mechanics of some of these things. But I think, as they start to go to market, we should be able to invest.

And there are a couple of things where we haven’t really faced up to yet. So, first of all, the private sector is investing in resilience, a) because it’s losing money, so it’s backstopping. And, secondly, because it can see how the world is being impacted by climate change, they are investing in their resilience in changed circumstances. That is captured as a cost in most countries in their accounts. That is not seen as an investment.

And also, I think in most countries – and certainly in the UN – we have no way to capture that. So we don’t really capture how much the private sector is already investing in its ability to just continue to operate under current climate conditions.

CB: It’s been really interesting over this year so far to see the Brazilian presidency of COP30 and also conversations at the Bonn talks in June explicitly referencing this idea of COP reform. What reforms would you propose or support?

RK: So, there’s no fixed British position on this yet, right? But I think what’s being discussed is there’s a utility to walking up to a mountain and putting a flag on the mountain every year, right? But, actually, we’re sort of in a more undulating landscape of implementation, where we need to be working throughout the year, right?

So, should there be Rio Trio summits every two years? People are talking about that. I think you could argue backwards and forwards, right or wrong, on that. What happens between the COPs? How do you bring the external world into the COPs? How do you let subnational actors and voices be heard at the COPs? These are all live topics and I think we need to move forward on most of them.

And then are we getting to the point where only certain countries can host them because they’re so big? I don’t know. Do you have thematic meetings throughout the year? How do we better keep real-time track of progress? So the next time we do a stocktake, in the world of AI and other things, is there a better and easier way? And can we still make that more transparent?

It would be great if the public could look at a sort of traffic-light spreadsheet and [say], “OK, we’re on track and not on track”. So I think all of those [questions are being asked] and it poses real challenges to the UN, which itself is in a process of reform now, in part, as a response to the US’s sort of questioning of the efficacy of parts of the UN, but also, I think, because the world is significantly changing.

CB: In your role, you’ve been in meetings over recent months with counterparts in Indonesia, China, South Africa, etc. What have been, particularly for some of those key countries, what have been the specific points of conversation you’ve had with them? Is it all about finance, or other important ingredients to those discussions?

RK: No, I think the starting point is, well, a lot of it is about finance, but, it’s about investment. It’s about growth and investment, right? It’s green growth and investment. And then finance fits into that.

So it’s not the finer points of the way finance is described in the COP. It is huge demand for the technical capacity of the UK, whether it is sophisticated demand-side management in grids, or how we regulate and how we oversee our grids in this country. Or how we exited from coal. Or what we are planning on some other dimension of the energy transition, our technical capacity and civil nuclear management. The desire for UK Inc’s knowledge about how we do things on things that we have actually been successful in – and also lessons of failure as well, honestly. So, everybody is figuring out how to do this.

There’s a strong desire for a pragmatic UK that is capable of convening across traditional blocs. I think we are seen as having a relationship with Brussels, a relationship with the US, a dialogue with China, a new free-trade agreement with India and a dialogue with India, [as well as] relationships through the Commonwealth and directly with small island states and least developed countries. We are seen as someone that already has bridges in place [and] could help strengthen those bridges.

So, what’s really been striking to me is it isn’t a conversation about, “oh woe is us, what we’re going to do?” It’s a conversation like: “I have a 10% growth rate. I need to do this. I would like you to be investing more.” It’s that kind of conversation – and that’s whether I’m meeting the minister of energy, finance, mines, environment, whoever I’m meeting with, that’s kind of the focus.

So I’m not Pollyanna about this, but people have got really big problems in front of them and it’s about their economic growth and development. And it’s, how can we help? I think the other thing that’s really coming through is just the cost of the impacts already, every flood, every failed harvest, every pressure on a city. I mean, this is really, really, really now…you can’t escape it, every country’s in the middle of it, we’re in the middle of it, domestically. And how this gets addressed, I think it is a question for this COP and the next COP.

CB: Other than the prime minister [Keir Starmer] and also your bosses, Ed Miliband and David Lammy, you’re kind of one of the key “faces” on the international stage representing just how invested the current UK government is in this issue of climate change. How do you think the UK’s role in this is perceived by other countries, ranging from China and other climate vulnerables, to the likes of the EU and the US?

RK: So, I think my perception of the external view of us is that – and what we’ve been trying to project as well – is “don’t do as we say, do as we do”. That means that we need to do a lot of things building on [the progress we’ve already made]. And I think that the beginning of the inward investment, just in the last year, into the clean-energy economy here [in the UK], that’s upwards of £50bn. So we’re open for business.

There’s one thing to talk about the City as a green financial centre, which has happened because of the leadership of City leaders, but now there’s this dialogue between government and the City about how to make that even broader. And, of course, that would mean becoming the western world’s heart of the carbon markets, if Singapore is the heart of the sort of eastern world’s carbon markets. It would mean that London helps define what a good biodiversity credit looks like, what a standardised swap looks like. There’s so much more that could be done there and I think that that’s what people want from us, but it’s also what we are trying to be able to build ourselves up to offer.

I think people want us engaged in the dialogue. So there’s a strategic dialogue with China. You could say that the strategic dialogue between China, the UK and the EU is the sort of triangular underpinning, actually, of the strength of the Paris Agreement. And, of course, we’re just about to see the EU-China summit, which will be important.

Our dialogue with India is interesting, right? So India found itself in a very difficult position at the end of COP29. In our free-trade agreement and in our strategic partnership with India climate and energy is a big part of that conversation. That’s all about technical lessons, learning and investment in both directions.

And then with the EU, the EU/UK reset is in the rearview mirror now. So now we need to get into the negotiations around the proximity, or the alignment between the ETSs [emissions trading schemes] shared stances on other issues and then how we show up as the sort of “liberal west” in the COPs.

So, the world is changing. It’s flatter. The BRICS are more and more important. We have, I think, powerful relationships with a number of key countries within the BRICS and that is an object of foreign policy, as well. And so how do we as the UK build up our agility, our global sense of the world and our place in it, so that we can help everybody stay on track for the kind of results we need by the middle of the century.

But what I think we’re very forceful about is that you can’t take two to three years out of climate conferences just because the world’s really difficult. And that has to be argued domestically and it has to be argued with [our] international partners. We don’t have time to just sort of say, “Oh, well, we’ll come back to that”. We have to build it in now.

CB: Specifically around the damage that’s been caused by the current trade tensions caused by the US, how do you think that is directly impacting the kind of wider climate negotiations, but also just the push towards the transition? Is this a key stumbling block now?

RK: Investment flows when everybody feels confident, right? And it just begs a whole bunch of questions and I think that’s slowing down investment decision-making.

So, I don’t think it’s specifically anti-climate, or whatever. I think it’s, generically, like if I don’t know if the tariff is 10%, 20%, 25%, 56%, whatever, well, let me put it off till the next quarter to make that investment decision. And I think that that’s what we’re beginning to see. So that, for me, is the main [thing]…It’s the hesitancy that it puts in the mind of government, but also in the mind of investors and the private sector.

I mean, it’s a little bit too early to tell in terms of investment not going into the US and going elsewhere, or individual supply chains for individual pieces of the clean transition, but I think the main problem globally is just this hesitation.

I would have to say that other things, including, perhaps, the ability of NOAA [National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration] and the National Weather Service to continue to provide services to the Caribbean and Central America, that the impact of the cuts to USAid [US Agency for International Development] in certain geographies are profound. But, generally, the sort of tariff era we’re in, the risk is that it slows down the investment in the clean-energy transition at a time when it needs to speed up.

CB: With the US in retreat, is China now the most important country in the world when it comes to climate action? Can you give a sense of your recent conversations with your Chinese counterparts, both recently, but also how they might have changed over recent years?

RK: So China’s posture before…there is obviously a China-US dynamic, but aside from that dynamic, China’s posture has been that “we are multilateralists, we want multilateralism to thrive and we’re all in”, right? And they’ve repeated that in every possible forum and they’ve repeated that at the highest level, including in [Chinese president] Xi Jinping’s statements at the leaders summit hosted by the UN secretary-general [António Guterres] and [Brazil’s] President Lula. So they are in.

Are they taking up space that would have been occupied by the US before? Nature abhors a vacuum, so all kinds of people are coming in. And the world moves towards China because of the fact that, over the last 25 years, it’s emerged as dominant in the solar-energy supply chain, with all of the problems that that has brought as well.

And then, financially, because of the way in which the [UNFCCC] convention is framed, they are a developing country, so they quite rightly only want their contributions to be made voluntarily, but they are a major player, right?

They already were a major player. The world had already shifted in that direction. Our conversation with them is technical and collegial and, I think, really frank. And we hosted the ministry of environment [Huang Runqiu] here recently [and] met with both the secretary of state for energy and the secretary of state for environment, and I was just really struck at how wide-ranging the issues that they would like to discuss is, and just how sort of practical, pragmatic and how sort of sleeves rolled up it was. And I think that’s also what is observed in their relationship with the conversations they’re having at a technical level in Brussels.

So it’s a complicated, nuanced relationship across all issues of trade, security, investment and climate. But they’re living in a world where climate is going to disrupt their own economy, if they don’t build their resilience. And of course, China has its tentacles everywhere. So maintaining our ability to talk to China about these issues, notwithstanding all of the other tensions and difficulties and opportunities, is “sine qua non”, I think. So let’s see how they show up in Belém.

CB: Just the final question, which is a bit more of a personal question, which we like to ask this of our interviewees, what is your first moment of epiphany on climate change? Can you remember? Was it a book, a lecture, a documentary, a conversation, or a trip you went on? Can you remember where that penny really dropped and you thought, I need to work on this, professionally and hard?

RK: There were two. One was very early on in my career. I was working on international youth politics in Europe. And, at that time, the Iron Curtain was up – I’m that old [smiles] – and sulfuric acid would go up from power plants in the east and it would land in the west and destroy the forest in Norway. And the conversation was: “Well, do you have ever-higher limits on the Norwegian industry?” Or do you go to Poland and say: “Look, can we put scrubbers on your [power plants]?” And it was the interconnected [nature of all this].

And, of course, at that time, young people in both east and western Europe wanted to build a more benign presence of Europe in the world and we wanted to be united, right? Or wanted the wall to come down. And that was a question of peace and environment. And it was the environment movement that was at the heart of the peace movement. So that was [a moment of thinking], “so I want to work on this”.

And I remember some very, very, strange meeting somewhere in eastern Europe and watching a really badly made movie about migration and the idea that, if we didn’t cope with this [climate change], people would come in boats across, presumably the Mediterranean. And I was, like, this is a global problem.

The second thing was just before Paris [in 2015]. There were these sort of famous rumours about all these women that got together and worked together to try to help the Paris Agreement happen. And so I was in a meeting with a bunch of women and two leaders from emerging markets, developing economies – it was very juxtaposed, because I was, at that point, the vice president of the World Bank – and we were having a discussion about 1.5C and whether, did it make sense as a strategy. And I was like: “2C is going to be difficult enough, you want to negotiate 1.5C?” And then we sort of broke. And then the next morning, we reconvened and we were just reflecting on the day before’s conversations and they both said to me: “You can’t just throw these numbers around as if they’re points of negotiation, because, for my culture, the difference between 2C and 1.5C is existence or non-existence”. And that was important.

CB: OK, thank you very much, Rachel.

RK: Thank you.

The post The Carbon Brief Interview: UK climate envoy Rachel Kyte appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

DeBriefed 6 February 2026: US secret climate panel ‘unlawful’ | China’s clean energy boon | Can humans reverse nature loss?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Secrets and layoffs

UNLAWFUL PANEL: A federal judge ruled that the US energy department “violated the law when secretary Chris Wright handpicked five researchers who rejected the scientific consensus on climate change to work in secret on a sweeping government report on global warming”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper explained that a 1972 law “does not allow agencies to recruit or rely on secret groups for the purposes of policymaking”. A Carbon Brief factcheck found more than 100 false or misleading claims in the report.

DARKNESS DESCENDS: The Washington Post reportedly sent layoff notices to “at least 14” of its climate journalists, as part of a wider move from the newspaper’s billionaire owner, Jeff Bezos, to eliminate 300 jobs at the publication, claimed Climate Colored Goggles. After the layoffs, the newspaper will have five journalists left on its award-winning climate desk, according to the substack run by a former climate reporter at the Los Angeles Times. It comes after CBS News laid off most of its climate team in October, it added.

WIND UNBLOCKED: Elsewhere, a separate federal ruling said that a wind project off the coast of New York state can continue, which now means that “all five offshore wind projects halted by the Trump administration in December can resume construction”, said Reuters. Bloomberg added that “Ørsted said it has spent $7bn on the development, which is 45% complete”.

Around the world

- CHANGING TIDES: The EU is “mulling a new strategy” in climate diplomacy after struggling to gather support for “faster, more ambitious action to cut planet-heating emissions” at last year’s UN climate summit COP30, reported Reuters.

- FINANCE ‘CUT’: The UK government is planning to cut climate finance by more than a fifth, from £11.6bn over the past five years to £9bn in the next five, according to the Guardian.

- BIG PLANS: India’s 2026 budget included a new $2.2bn funding push for carbon capture technologies, reported Carbon Brief. The budget also outlined support for renewables and the mining and processing of critical minerals.

- MOROCCO FLOODS: More than 140,000 people have been evacuated in Morocco as “heavy rainfall and water releases from overfilled dams led to flooding”, reported the Associated Press.

- CASHFLOW: “Flawed” economic models used by governments and financial bodies “ignor[e] shocks from extreme weather and climate tipping points”, posing the risk of a “global financial crash”, according to a Carbon Tracker report covered by the Guardian.

- HEATING UP: The International Olympic Committee is discussing options to hold future winter games earlier in the year “because of the effects of warmer temperatures”, said the Associated Press.

54%

The increase in new solar capacity installed in Africa over 2024-25 – the continent’s fastest growth on record, according to a Global Solar Council report covered by Bloomberg.

Latest climate research

- Arctic warming significantly postpones the retreat of the Afro-Asian summer monsoon, worsening autumn rainfall | Environmental Research Letters

- “Positive” images of heatwaves reduce the impact of messages about extreme heat, according to a survey of 4,000 US adults | Environmental Communication

- Greenland’s “peripheral” glaciers are projected to lose nearly one-fifth of their total area and almost one-third of their total volume by 2100 under a low-emissions scenario | The Cryosphere

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

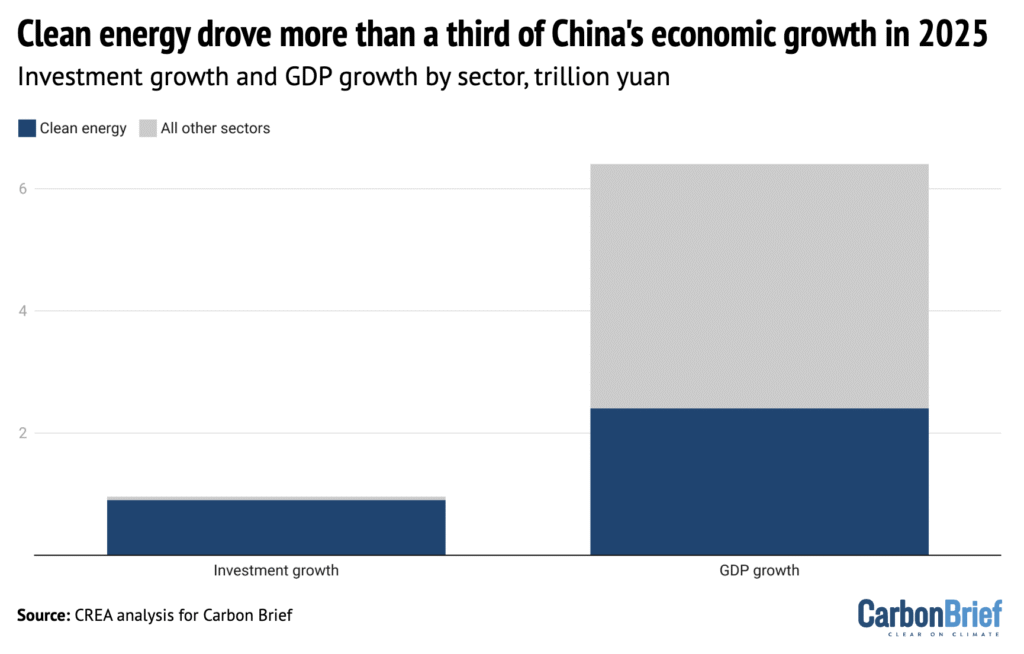

Captured

Solar power, electric vehicles and other clean-energy technologies drove more than a third of the growth in China’s economy in 2025 – and more than 90% of the rise in investment, according to new analysis for Carbon Brief (shown in blue above). Clean-energy sectors contributed a record 15.4tn yuan ($2.1tn) in 2025, some 11.4% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) – comparable to the economies of Brazil or Canada, the analysis said.

Spotlight

Can humans reverse nature decline?

This week, Carbon Brief travelled to a UN event in Manchester, UK to speak to biodiversity scientists about the chances of reversing nature loss.

Officials from more than 150 countries arrived in Manchester this week to approve a new UN report on how nature underpins economic prosperity.

The meeting comes just four years before nations are due to meet a global target to halt and reverse biodiversity loss, agreed in 2022 under the landmark “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework” (GBF).

At the sidelines of the meeting, Carbon Brief spoke to a range of scientists about humanity’s chances of meeting the 2030 goal. Their answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Dr David Obura, ecologist and chair of Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)

We can’t halt and reverse the decline of every ecosystem. But we can try to “bend the curve” or halt and reverse the drivers of decline. That’s the economic drivers, the indirect drivers and the values shifts we need to have. What the GBF aspires to do, in terms of halting and reversing biodiversity loss, we can put in place the enabling drivers for that by 2030, but we won’t be able to do it fast enough at this point to halt [the loss] of all ecosystems.

Dr Luthando Dziba, executive secretary of IPBES

Countries are due to report on progress by the end of February this year on their national strategies to the Convention on Biological Diversity [CBD]. Once we get that, coupled with a process that is ongoing within the CBD, which is called the global stocktake, I think that’s going to give insights on progress as to whether this is possible to achieve by 2030…Are we on the right trajectory? I think we are and hopefully we will continue to move towards the final destination of having halted biodiversity loss, but also of living in harmony with nature.

Prof Laura Pereira, scientist at the Global Change Institute at Wits University, South Africa

At the global level, I think it’s very unlikely that we’re going to achieve the overall goal of halting biodiversity loss by 2030. That being said, I think we will make substantial inroads towards achieving our longer term targets. There is a lot of hope, but we’ve also got to be very aware that we have not necessarily seen the transformative changes that are going to be needed to really reverse the impacts on biodiversity.

Dr David Cooper, chair of the UK’s Joint Nature Conservation Committee and former executive secretary of the Convention on Biological Diversity

It’s important to look at the GBF as a whole…I think it is possible to achieve those targets, or at least most of them, and to make substantial progress towards them. It is possible, still, to take action to put nature on a path to recovery. We’ll have to increasingly look at the drivers.

Prof Andrew Gonzalez, McGill University professor and co-chair of an IPBES biodiversity monitoring assessment

I think for many of the 23 targets across the GBF, it’s going to be challenging to hit those by 2030. I think we’re looking at a process that’s starting now in earnest as countries [implement steps and measure progress]…You have to align efforts for conserving nature, the economics of protecting nature [and] the social dimensions of that, and who benefits, whose rights are preserved and protected.

Neville Ash, director of the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre

The ambitions in the 2030 targets are very high, so it’s going to be a stretch for many governments to make the actions necessary to achieve those targets, but even if we make all the actions in the next four years, it doesn’t mean we halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. It means we put the action in place to enable that to happen in the future…The important thing at this stage is the urgent action to address the loss of biodiversity, with the result of that finding its way through by the ambition of 2050 of living in harmony with nature.

Prof Pam McElwee, Rutgers University professor and co-chair of an IPBES “nexus assessment” report

If you look at all of the available evidence, it’s pretty clear that we’re going to keep experiencing biodiversity decline. I mean, it’s fairly similar to the 1.5C climate target. We are not going to meet that either. But that doesn’t mean that you slow down the ambition…even though you recognise that we probably won’t meet that specific timebound target, that’s all the more reason to continue to do what we’re doing and, in fact, accelerate action.

Watch, read, listen

OIL IMPACTS: Gas flaring has risen in the Niger Delta since oil and gas major Shell sold its assets in the Nigerian “oil hub”, a Climate Home News investigation found.

LOW SNOW: The Washington Post explored how “climate change is making the Winter Olympics harder to host”.

CULTURE WARS: A Media Confidential podcast examined when climate coverage in the UK became “part of the culture wars”.

Coming up

- 2-8 February: 12th session of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), Manchester, UK

- 8 February: Japanese general election

- 8 February: Portugal presidential election

- 11 February: Barbados general election

- 11-12 February: UN climate chief Simon Stiell due to speak in Istanbul, Turkey

Pick of the jobs

- UK Met Office, senior climate science communicator | Salary: £43,081-£46,728. Location: Exeter, UK

- Canadian Red Cross, programme officer, Indigenous operations – disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation | Salary: $56,520-$60,053. Location: Manitoba, Canada

- Aldersgate Group, policy officer | Salary: £33,949-£39,253. Location: London (hybrid)

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 6 February 2026: US secret climate panel ‘unlawful’ | China’s clean energy boon | Can humans reverse nature loss? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

China Briefing 5 February 2026: Clean energy’s share of economy | Record renewables | Thawing relations with UK

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s China Briefing.

China Briefing handpicks and explains the most important climate and energy stories from China over the past fortnight. Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Solar and wind eclipsed coal

‘FIRST TIME IN HISTORY’: China’s total power capacity reached 3,890 gigawatts (GW) in 2025, according to a National Energy Administration (NEA) data release covered by industry news outlet International Energy Net. Of this, it said, solar capacity rose 35% to 1,200GW and wind capacity was up 23% to 640GW, while thermal capacity – which is mostly coal – grew 6% to just over 1,500GW. This marks the “first time in history” that wind and solar capacity has outranked coal capacity in China’s power mix, reported the state-run newspaper China Daily. China’s grid-related energy storage capacity exceeded 213GW in 2025, said state news agency Xinhua. Meanwhile, clean-energy industries “drove more than 90%” of investment growth and more than half of GDP growth last year, said the Guardian in its coverage of new analysis for Carbon Brief. (See more in the spotlight below.)

DAWN FOR SOLAR: Solar power capacity alone may outpace coal in 2026, according to projections by the China Electricity Council (CEC), reported business news outlet 21st Century Business Herald. It added that non-fossil sources could account for 63% of the power mix this year, with coal falling to 31%. Separately, the China Renewable Energy Society said that annual wind-power additions could grow by between 600-980GW over the next five years, with annual additions of 120GW expected until 2028, said industry news outlet China Energy Net. China Energy Net also published the full CEC report.

STATE MEDIA VOICE: Xinhua published several energy- and climate-related articles in a series on the 15th five-year plan. One said that becoming a low-carbon energy “powerhouse” will support decarbonisation efforts, strengthen industrial innovation and improve China’s “global competitive edge and standing”. Another stated that coal consumption is “expected” to peak around 2027, with continued “growth” in the power and chemicals sector, while oil has already peaked. A third noted that distributed energy systems better matched the “characteristics of renewable energy” than centralised ones, but warned against “blind” expansion and insufficient supporting infrastructure. Others in the series discussed biodiversity and environmental protection and recycling of clean-energy technology. Meanwhile, the communist party-affiliated People’s Daily said that oil will continue to play a “vital role” in China, even after demand peaks.

Starmer and Xi endorsed clean-energy cooperation

CLIMATE PARTNERSHIP: UK prime minister Keir Starmer and Chinese president Xi Jinping pledged in Beijing to deepen cooperation on “green energy”, reported finance news outlet Caixin. They also agreed to establish a “China-UK high-level climate and nature partnership”, said China Daily. Xi told Starmer that the two countries should “carry out joint research and industrial transformation” in new energy and low-carbon technologies, according to Xinhua. It also cited Xi as saying China “hopes” the UK will provide a “fair” business environment for Chinese companies.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “China Briefing” email newsletter. All you need to know about the latest developments relating to China and climate change. Sent to your inbox every Thursday.

OCTOPUS OVERSEAS: During the visit, UK power-trading company Octopus Energy and Chinese energy services firm PCG Power announced they would be starting a new joint venture in China, named Bitong Energy, reported industry news outlet PV Magazine. The move “marks a notable direct entry” of a foreign company into China’s “tightly regulated electricity market”, said Caixin.

PUSH AND PULL: UK policymakers also visited Chinese clean-energy technology manufacturer Envision in Shanghai, reported finance news outlet Yicai. It quoted UK business secretary Peter Kyle emphasising that partnering with companies “like Envision” on sustainability is a “really important part of our future”, particularly in terms of job creation in the UK. Trade minister Chris Bryant told Radio Scotland Breakfast that the government will decide on Chinese wind turbine manufacturer Mingyang’s plans for a Scotland factory “soon”. Researchers at the thinktank Oxford Institute for Energy Studies wrote in a guest post for Carbon Brief that greater Chinese competition in Europe’s wind market could “help spur competition in Europe”, if localisation rules and “other guardrails” are applied.

More China news

- LIFE SUPPORT: China will update its coal capacity payment mechanism, which will raise thresholds for coal-fired power plants and expand to cover gas-fired power and pumped and new-energy storage, reported current affairs outlet China News.

- FRONTIER TECH: The world’s “largest compressed-air power storage plant” has begun operating in China, said Bloomberg.

- PARTNERSHIP A ‘MISTAKE’: The EU launched a “foreign subsidies” probe into Chinese wind turbine company Goldwind, said the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post. EU climate chief Wopke Hoekstra said the bloc must resist China’s pull in clean technologies, according to Bloomberg.

- TRADE SPAT: The World Trade Organization “backed a complaint by China” that the US Inflation Reduction Act “discriminated against” Chinese cleantech exports, said Reuters.

- NEW RULES: China has set “new regulations” for the Waliguan Baseline Observatory, which provides “key scientific references for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change”, said the People’s Daily.

Captured

New or reactivated proposals for coal-fired power plants in China totalled 161GW in 2025, according to a new report covered by Carbon Brief.

Spotlight

Clean energy drove China’s economic growth in 2025

New analysis for Carbon Brief finds that clean-energy sectors contributed the equivalent of $2.1tn to China’s economy last year, making it a key driver of growth. However, headwinds in 2026 could restrict growth going forward – especially for the solar sector.

Below is an excerpt from the article, which can be read in full on Carbon Brief’s website.

Solar power, electric vehicles (EVs) and other clean-energy technologies drove more than a third of the growth in China’s economy in 2025 – and more than 90% of the rise in investment.

Clean-energy sectors contributed a record 15.4tn yuan ($2.1tn) in 2025, some 11.4% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP)

Analysis shows that China’s clean-energy sectors nearly doubled in real value between 2022-25 and – if they were a country – would now be the 8th-largest economy in the world.

These investments in clean-energy manufacturing represent a large bet on the energy transition in China and overseas, creating an incentive for the government and enterprises to keep the boom going.

However, there is uncertainty about what will happen this year and beyond, particularly due to a new pricing system, worsening industrial “overcapacity” and trade tensions.

Outperforming the wider economy

China’s clean-energy economy continues to grow far more quickly than the wider economy, making an outsized contribution to annual growth.

Without these sectors, China’s GDP would have expanded by 3.5% in 2025 instead of the reported 5.0%, missing the target of “around 5%” growth by a wide margin.

Clean energy made a crucial contribution during a challenging year, when promoting economic growth was the foremost aim for policymakers.

In 2024, EVs and solar had been the largest growth drivers. In 2025, it was EVs and batteries, which delivered 44% of the economic impact and more than half of the growth of the clean-energy industries.

The next largest subsector was clean-power generation, transmission and storage, which made up 40% of the contribution to GDP and 30% of the growth in 2025.

Within the electricity sector, the largest drivers were growth in investment in wind and solar power generation capacity, along with growth in power output from solar and wind, followed by the exports of solar-power equipment and materials.

But investment in solar-panel supply chains, a major growth driver in 2022-23, continued to fall for the second year, as the government made efforts to rein in overcapacity and “irrational” price competition.

Headwinds for solar

Ongoing investment of hundreds of billions of dollars represents a gigantic bet on a continuing global energy transition.

However, developments next year and beyond are unclear, particularly for solar. A new pricing system for renewable power is creating uncertainty, while central government targets have been set far below current rates of clean-electricity additions.

Investment in solar-power generation and solar manufacturing declined in the second half of the year.

The reduction in the prices of clean-energy technology has been so dramatic that when the prices for GDP statistics are updated, the sectors’ contribution to real GDP – adjusted for inflation or, in this case deflation – will be revised down.

Nevertheless, the key economic role of the industry creates a strong motivation to keep the clean-energy boom going. A slowdown in the domestic market could also undermine efforts to stem overcapacity and inflame trade tensions by increasing pressure on exports to absorb supply.

Local governments and state-owned enterprises will also influence the outlook for the sector.

Provincial governments have a lot of leeway in implementing the new electricity markets and contracting systems for renewable power generation. The new five-year plans, to be published this year, will, therefore, be of major importance.

This spotlight was written for Carbon Brief by Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), and Belinda Schaepe, China policy analyst at CREA. CREA China analysts Qi Qin and Chengcheng Qiu contributed research.

Watch, read, listen

PROVINCE INFLUENCE: The Institute for Global Decarbonization Progress, a Beijing-based thinktank, published a report examining the climate-related statements in provincial recommendations for the 15th five-year plan.

‘PIVOT’?: The Outrage + Optimism podcast spoke with the University of Bath’s Dr Yixian Sun about whether China sees itself as a climate leader and what its role in climate negotiations could be going forward.

COOKING FOR CLEAN-TECH: Caixin covered rising demand for China’s “gutter oil” as companies “scramble” to decarbonise.

DON’T GO IT ALONE: China News broadcast the Chinese foreign ministry’s response to the withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement, with spokeswoman Mao Ning saying “no country can remain unaffected” by climate change.

$6.8tn

The current size of China’s green-finance economy, including loans, bonds and equity, according to Dr Ma Jun, the Institute of Finance and Sustainability’s president,in a report launch event attended by Carbon Brief. Dr Ma added that “green loans” make up 16% of all loans in China, with some areas seeing them take a 34% share.

New science

- China’s official emissions inventories have overestimated its hydrofluorocarbon emissions by an average of 117m tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (mtCO2e) every year since 2017 | Nature Geoscience

- “Intensified forest management efforts” in China from 2010 onwards have been linked to an acceleration in carbon absorption by plants and soils | Communications Earth and Environment

Recently published on WeChat

China Briefing is written by Anika Patel and edited by Simon Evans. Please send tips and feedback to china@carbonbrief.org

The post China Briefing 5 February 2026: Clean energy’s share of economy | Record renewables | Thawing relations with UK appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Congress rescues aid budget from Trump’s “evisceration” but climate misses out

Under pressure from Congress, President Donald Trump quietly signed into law a funding package that provides billions of dollars more in foreign assistance spending than he had originally wanted to for the fiscal year between October 2025 and September 2026.

The legislation allocates $50 billion, $9 billion less than the level agreed the previous year under President Biden but $19 billion more than Trump proposed, restoring health and humanitarian aid spending to near pre-Trump levels.

Democratic Senator Patty Murray, vice-chair of the committee on appropriations, said that “while including some programmatic funding cuts, the bill rejects the Trump administration’s evisceration of US foreign assistance programmes”.

But, with climate a divisive issue in the US, spending on dedicated climate programmes was largely absent. Clarence Edwards, executive director of E3G’s US office, told Climate Home News that “the era of large US government investment in climate policy is over, at least for the foreseeable future”.

The package ruled out any support for the Climate Investment Funds’ Clean Technology Fund, which supports low-carbon technologies in developing countries and had received $150 million from the US in the previous fiscal year.

The US also made no pledge to the Africa Development Fund (ADF) – a mechanism run by the African Development Bank that provides grants and low-interest loans to the poorest African nations. A government spokesperson told Reuters that decision reflected concerns that “like too many other institutions, the ADF has adopted a disproportionate focus on climate change, gender, and social issues”.

GEF spared from cuts

Trump did, however, agree to Congress’s request to make $150 million – more than last year – available for the Global Environment Facility (GEF), which tackles environmental issues like biodiversity loss, land degradation and climate change.

Edwards said that GEF funding “survived due to Congressional pushback and a refocus on non-climate priorities like biodiversity, plastics and ocean ecosystems, per US Treasury guidance”.

Congress also pressured Trump into giving $54 million to the Rome-based International Fund for Agricultural Development. Its goals include helping small-scale farmers adapt to climate change and reduce emissions.

Without any pressure from Congress, Trump approved tens of millions of dollars each for multilateral development banks in Asia, Africa and Europe and just over a billion dollars for the World Bank’s International Development Association, which funds development projects in the world’s poorest countries.

As most of these banks have climate programmes and goals, much of this money is likely to be spent on climate action. The largest lender, the World Bank, aims to devote 45% of its finance to climate programmes, although, as Climate Home News has reported, its definition of climate spending is considered too loose by some analysts.

The bill also earmarks $830 million – nearly triple what Trump originally wanted – for the Millennium Challenge Corporation, a George W. Bush-era institution that has increasingly backed climate-focussed projects like transmission lines to bring clean hydropower to cities in Nepal.

No funding boost for DFC

While Congress largely increased spending, it rejected Trump’s call for nearly $4 billion for the Development Finance Corporation (DFC), granting just under $1 billion instead – similar to previous years.

Under Biden, there had been a push to get the DFC to support clean energy projects. But the Trump administration ended DFC’s support for projects like South Africa’s clean energy transition.

At a recent board meeting, the DFC’s board – now dominated by Trump administration officials – approved US financial support for Chevron Mediterranean Limited, the developers of an Israeli gas field.

Kate DeAngelis, deputy director at Friends of the Earth US told Climate Home News it was good for the climate that Trump had not been able to boost the DFC’s budget. “DFC seems set up to focus mainly on the dirtiest deals without any focus on development,” she said.

US Congressional elections in November could lead to Democrats retaking control of one or both houses of Congress. Edwards said that “Democratic gains might restore funding [in the next fiscal year], while Republican holds would likely extend cuts”.

But he warned that “budgetary pressures and a murky economic environment don’t hold promise of increases in US funding for foreign assistance and climate programs, regardless of which party controls Congress”.

The post Congress rescues aid budget from Trump’s “evisceration” but climate misses out appeared first on Climate Home News.

Congress rescues aid budget from Trump’s “evisceration” but climate misses out

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Renewable Energy2 years ago

GAF Energy Completes Construction of Second Manufacturing Facility