Countries that pump out large amounts of greenhouse gases could “retain or expand” their fossil fuel industries while treating such emissions as “inevitable” in their net-zero accounting, according to a new study.

Some sectors, such as livestock farming and heavy industry, are viewed as particularly hard to decarbonise. This is due, in part, to a perceived lack of cheap technological solutions.

Any “residual emissions” from these practices will have to be balanced by removals from the atmosphere, if nations want to claim they have achieved their net-zero goals.

The new study, published in One Earth, analyses the strategies that nations have submitted to the UN to understand their approach to these emissions, and how they define them.

It finds significant uncertainty, with just 26 out of 71 countries with long-term plans having outlined how much they expect to still be emitting by 2050.

These nations alone say their residual emissions could be up to 2.9bn tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (GtCO2e) – equivalent to around 5% of the current global total.

Fossil-fuel producing nations, such as Australia and Canada, plan to continue producing large volumes of emissions – before removing them via carbon capture technologies or paying for them to be offset elsewhere.

The study authors warn that the slow development and rollout of CO2 removal technologies means this approach could lead to net-zero ambitions ending in “failure”.

Hard-to-abate?

“Residual” emissions are defined as those that remain once a nation, or some other entity, has gone as far as it thinks is possible to cut greenhouse gas emissions.

The concept is closely tied with the net-zero targets that many nations have set for the middle of the century. A country must remove CO2 from the atmosphere that is equivalent in volume to its residual emissions, in order to say it has reached net-zero.

The amount of residual emissions each country is left with therefore dictates how much it will have to invest in CO2 removal – either by planting trees or building machines that directly remove the CO2 from the atmosphere.

So far, countries have shown very little progress in developing technologies to remove CO2.

Yet, as the new study explains, “there is a tendency to treat residual emissions as inevitable”. One key reason for this is that these emissions are expected to largely come from so-called “hard-to-abate” sectors.

These sectors are generally framed as those that lack cheap and widely available technologies to drastically cut their emissions. Examples include steel production, aviation and many aspects of livestock agriculture, such as rearing cows, growing rice and using fertilisers..

Yet, despite these common framings, in practice, both residual emissions and hard-to-abate sectors remain poorly defined. Moreover, there is a growing body of evidence suggesting that even “hard-to-abate” sectors can feasibly be decarbonised using available technologies.

According to Prof Naomi Vaughan, a climate change researcher at the University of East Anglia (UEA) and one of the new study’s co-authors, this means “net-zero can hide a multitude of sins”. Speaking to Carbon Brief, she asks:

“What are you choosing – as an industry or as a country – to decide is hard to abate…And what genuinely is?”

In order to interrogate this, the team led by Harry Smith, a UEA PhD student focusing on the role of CO2 removal in climate policy, set out to understand what different countries were describing as “residual emissions” and how they were justifying this description.

Big residuals

Under the Paris Agreement, nations are encouraged to submit long-term low-emission development strategies (LT-LEDS). If a country has a mid-century net-zero target, this document will explain how it intends to get there.

In their study, Smith and his colleagues analyse every LT-LEDS submitted to the UN by October 2023 – covering a total of 67 countries. They also include four extra long-term strategies produced by EU member states, but not submitted to the UN.

The 71 nations with long-term strategies for tackling climate change cover 71% of global emissions, the study notes.

However, the majority – 41 in total – do not quantify residual emissions at all in their plans. These include major emitters with net-zero targets, such as China, India and Russia.

The researchers identify 26 countries that have calculated the amount of emissions they expect to still be producing at the point they reach net-zero.

In total, this amounts to between 2.6-2.9GtCO2e, excluding emissions from land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF). (The range results from countries including several different scenarios in their strategies.)

The study also compares the scale of each nation’s residual emissions to the highest level its emissions have reached in a year. If countries are yet to peak, data from 2021 was used.

The authors conclude that, on average, the 16 developed “Annex I” countries assessed in this study plan on still producing 21% of their peak emissions when they reach net-zero.

Meanwhile, the nine developing and emerging “Annex II” economies expect to continue producing 34% of their peak emissions, the study finds. This estimate excludes Cambodia, which plans to keep increasing its emissions but cancelling them out by turning its extensive forests into a net carbon sink.

The chart below shows residual emissions (red) as a share of each nation’s peak emissions (blue) – or its most recent annual emissions, if its emissions have not yet peaked. Residual emissions from the US alone are set to be higher than the total emissions of nearly every other country.

Justifying emissions

To understand more about how governments justify the residual emissions in their strategies, the researchers analyse the sectors where emissions remain high out into the second half of this century.

Overall, agriculture is expected to see the least progress in emissions reductions, contributing roughly one-third of residual emissions across all the nations assessed, the study finds.

Methane from livestock and emissions from fertilisers are frequently cited as some of the “hardest-to-abate”. Developed countries only expect their agricultural emissions to drop 37%, on average, by the time they hit net-zero.

(International aviation and shipping, while viewed as some of the hardest sectors to decarbonise, are simply excluded from most countries’ long-term plans, meaning they do not feature prominently in this analysis.)

The researchers also look in greater depth at the rationales given by each country for defining emissions as “residual” or “hard-to-abate”, by analysing 357 statements on the topic within the long-term strategies. They group the statements into different categories, based on which sectors are described and the type of language used.

As the chart below shows, countries frequently provide no justification at all for their continued production of residual emissions in particular sectors.

The definition of “residual” varies considerably between countries, with governments focusing on different aspects depending on their circumstances. Smith tells Carbon Brief:

“What you find is this range of rationales [that are] not just technical…They’re not just political either…It’s a kind of pick your buffet of rationales.”

The most common arguments concern residual emissions from industry and transport – particularly the production of cement and steel, the emissions of F-gases and domestic aviation and shipping. (The researchers note a “mismatch” here, with arguments explaining residual emissions from agriculture often overlooked, despite it being the largest contributor.)

Countries most frequently cite the lack of new technologies and limits to existing ones as the reasons for continued emissions from these sectors.

Despite these assertions, hundreds of industry leaders from the heavy industry and heavy-duty transport sectors have described net-zero goals as “technically and financially possible by mid-century”.

For example, a recent report by the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) concluded that “the technologies to decarbonise hard-to-abate sectors have seen significant progress in recent years and are today largely available”.

‘Retain or expand’

The large amounts of residual emissions in most nations’ long-term strategies reveals that many are expecting to lean heavily on carbon removal to meet their net-zero targets, the study says.

The study notes that this “risks the credibility of their target[s] and risks a failure to meet national and global net-zero”, given the known limits to carbon removals.

In some cases, this could also mean shifting responsibility elsewhere by purchasing carbon offsets from other countries.

Moreover, the study adds that some nations “may attempt to retain or expand their fossil fuel production”, and pass off resulting emissions as “residual”. Vaughan explains that countries may lean towards looser definitions of residual emissions, if it benefits them:

“If you have a country with a very significant investment in the fossil fuel industry or extraction industries, then there is an incentive to imagine getting to net-zero where you still have quite a lot of emissions – but you’re using lot’s of CO2 removal to get there.”

The authors highlight Australia and Canada, two nations that currently produce large amounts of fossil fuels. Both include scenarios in their net-zero strategies – albeit at the high end of several potential outcomes – where emissions only fall by around half by 2050.

In Australia’s case, this scenario relies on purchasing large amounts of carbon offsets from other countries. Canada relies on very high use of CO2 removal technologies.

Prof Holly Jean Buck, a climate researcher at the University of Buffalo who published an initial investigation into residual emissions in countries’ LT-LEDS last year, but was not involved in this research. She says tackling the “ambiguity” around these emissions is key:

“We don’t know if countries are planning to phase out fossil fuels…We have infrastructure that has long lifetimes in terms of how long it takes to build it and how long it will be in operation. Without specificity around which sectors or activities we hope to fully decarbonise and electricity, it’s hard for countries to do that planning.”

More political

Experts tell Carbon Brief the new study is a welcome contribution to a relatively sparse literature on residual emissions.

Buck says it is a “thorough and careful” study that expands on her work, both by increasing the number of strategies assessed and broadening the scope of the analysis.

Her assessment only focused on high-ambition strategies for LT-LEDS from Annex I countries. The new research led by Smith and his colleagues includes a broader range of scenarios, and suggests that residual emissions could be even higher in 2050 than thought.

The study proposes a number of measures to tighten the definition of “residual” emissions and help countries better address them. This includes stronger reporting requirements for national strategies.

The researchers also propose separate targets for emissions reductions and CO2 removals, in order to prevent countries continuing to burn fossil fuels while simply pledging to remove emissions.

Dr William Lamb, a researcher at the Mercator Research Institute on Global Commons and Climate Change who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief he supports this idea and adds:

“I would also like to see the discussion of residual emissions become more political than it currently is. If countries were asking questions such as ‘how fast can we phase out fossil fuels?’ and ‘what human needs and services do we need to deliver, at minimum impact to the climate?’ then their long-term strategies would look very different.”

The post Major emitters ‘may retain or expand’ fossil fuels despite net-zero plans appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Major emitters ‘may retain or expand’ fossil fuels despite net-zero plans

Greenhouse Gases

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter.

Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Food inflation on the rise

DELUGE STRIKES FOOD: Extreme rainfall and flooding across the Mediterranean and north Africa has “battered the winter growing regions that feed Europe…threatening food price rises”, reported the Financial Times. Western France has “endured more than 36 days of continuous rain”, while farmers’ associations in Spain’s Andalusia estimate that “20% of all production has been lost”, it added. Policy expert David Barmes told the paper that the “latest storms were part of a wider pattern of climate shocks feeding into food price inflation”.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “Cropped” email newsletter. A fortnightly digest of food, land and nature news and views. Sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

NO BEEF: The UK’s beef farmers, meanwhile, “face a double blow” from climate change as “relentless rain forces them to keep cows indoors”, while last summer’s drought hit hay supplies, said another Financial Times article. At the same time, indoor growers in south England described a 60% increase in electricity standing charges as a “ticking timebomb” that could “force them to raise their prices or stop production, which will further fuel food price inflation”, wrote the Guardian.

‘TINDERBOX’ AND TARIFFS: A study, covered by the Guardian, warned that major extreme weather and other “shocks” could “spark social unrest and even food riots in the UK”. Experts cited “chronic” vulnerabilities, including climate change, low incomes, poor farming policy and “fragile” supply chains that have made the UK’s food system a “tinderbox”. A New York Times explainer noted that while trade could once guard against food supply shocks, barriers such as tariffs and export controls – which are being “increasingly” used by politicians – “can shut off that safety valve”.

El Niño looms

NEW ENSO INDEX: Researchers have developed a new index for calculating El Niño, the large-scale climate pattern that influences global weather and causes “billions in damages by bringing floods to some regions and drought to others”, reported CNN. It added that climate change is making it more difficult for scientists to observe El Niño patterns by warming up the entire ocean. The outlet said that with the new metric, “scientists can now see it earlier and our long-range weather forecasts will be improved for it.”

WARMING WARNING: Meanwhile, the US Climate Prediction Center announced that there is a 60% chance of the current La Niña conditions shifting towards a neutral state over the next few months, with an El Niño likely to follow in late spring, according to Reuters. The Vibes, a Malaysian news outlet, quoted a climate scientist saying: “If the El Niño does materialise, it could possibly push 2026 or 2027 as the warmest year on record, replacing 2024.”

CROP IMPACTS: Reuters noted that neutral conditions lead to “more stable weather and potentially better crop yields”. However, the newswire added, an El Niño state would mean “worsening drought conditions and issues for the next growing season” to Australia. El Niño also “typically brings a poor south-west monsoon to India, including droughts”, reported the Hindu’s Business Line. A 2024 guest post for Carbon Brief explained that El Niño is linked to crop failure in south-eastern Africa and south-east Asia.

News and views

- DAM-AG-ES: Several South Korean farmers filed a lawsuit against the country’s state-owned utility company, “seek[ing] financial compensation for climate-related agricultural damages”, reported United Press International. Meanwhile, a national climate change assessment for the Philippines found that the country “lost up to $219bn in agricultural damages from typhoons, floods and droughts” over 2000-10, according to Eco-Business.

- SCORCHED GRASS: South Africa’s Western Cape province is experiencing “one of the worst droughts in living memory”, which is “scorching grass and killing livestock”, said Reuters. The newswire wrote: “In 2015, a drought almost dried up the taps in the city; farmers say this one has been even more brutal than a decade ago.”

- NOUVELLE VEG: New guidelines published under France’s national food, nutrition and climate strategy “urged” citizens to “limit” their meat consumption, reported Euronews. The delayed strategy comes a month after the US government “upended decades of recommendations by touting consumption of red meat and full-fat dairy”, it noted.

- COURTING DISASTER: India’s top green court accepted the findings of a committee that “found no flaws” in greenlighting the Great Nicobar project that “will lead to the felling of a million trees” and translocating corals, reported Mongabay. The court found “no good ground to interfere”, despite “threats to a globally unique biodiversity hotspot” and Indigenous tribes at risk of displacement by the project, wrote Frontline.

- FISH FALLING: A new study found that fish biomass is “falling by 7.2% from as little as 0.1C of warming per decade”, noted the Guardian. While experts also pointed to the role of overfishing in marine life loss, marine ecologist and study lead author Dr Shahar Chaikin told the outlet: “Our research proves exactly what that biological cost [of warming] looks like underwater.”

- TOO HOT FOR COFFEE: According to new analysis by Climate Central, countries where coffee beans are grown “are becoming too hot to cultivate them”, reported the Guardian. The world’s top five coffee-growing countries faced “57 additional days of coffee-harming heat” annually because of climate change, it added.

Spotlight

Nature talks inch forward

This week, Carbon Brief covers the latest round of negotiations under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which occurred in Rome over 16-19 February.

The penultimate set of biodiversity negotiations before October’s Conference of the Parties ended in Rome last week, leaving plenty of unfinished business.

The CBD’s subsidiary body on implementation (SBI) met in the Italian capital for four days to discuss a range of issues, including biodiversity finance and reviewing progress towards the nature targets agreed under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

However, many of the major sticking points – particularly around finance – will have to wait until later this summer, leaving some observers worried about the capacity for delegates to get through a packed agenda at COP17.

The SBI, along with the subsidiary body on scientific, technical and technological advice (SBSTTA) will both meet in Nairobi, Kenya, later this summer for a final round of talks before COP17 kicks off in Yerevan, Armenia, on 19 October.

Money talks

Finance for nature has long been a sticking point at negotiations under the CBD.

Discussions on a new fund for biodiversity derailed biodiversity talks in Cali, Colombia, in autumn 2024, requiring resumed talks a few months later.

Despite this, finance was barely on the agenda at the SBI meetings in Rome. Delegates discussed three studies on the relationship between debt sustainability and implementation of nature plans, but the more substantive talks are set to take place at the next SBI meeting in Nairobi.

Several parties “highlighted concerns with the imbalance of work” on finance between these SBI talks and the next ones, reported Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

Lim Li Ching, senior researcher at Third World Network, noted that tensions around finance permeated every aspect of the talks. She told Carbon Brief:

“If you’re talking about the gender plan of action – if there’s little or no financial resources provided to actually put it into practice and implement it, then it’s [just] paper, right? Same with the reporting requirements and obligations.”

Monitoring and reporting

Closely linked to the issue of finance is the obligations of parties to report on their progress towards the goals and targets of the GBF.

Parties do so through the submission of national reports.

Several parties at the talks pointed to a lack of timely funding for driving delays in their reporting, according to ENB.

A note released by the CBD Secretariat in December said that no parties had submitted their national reports yet; by the time of the SBI meetings, only the EU had. It further noted that just 58 parties had submitted their national biodiversity plans, which were initially meant to be published by COP16, in October 2024.

Linda Krueger, director of biodiversity and infrastructure policy at the environmental not-for-profit Nature Conservancy, told Carbon Brief that despite the sparse submissions, parties are “very focused on the national report preparation”. She added:

“Everybody wants to be able to show that we’re on the path and that there still is a pathway to getting to 2030 that’s positive and largely in the right direction.”

Watch, read, listen

NET LOSS: Nigeria’s marine life is being “threatened” by “ghost gear” – nets and other fishing equipment discarded in the ocean – said Dialogue Earth.

COMEBACK CAUSALITY: A Vox long-read looked at whether Costa Rica’s “payments for ecosystem services” programme helped the country turn a corner on deforestation.

HOMEGROWN GOALS: A Straits Times podcast discussed whether import-dependent Singapore can afford to shelve its goal to produce 30% of its food locally by 2030.

‘RUSTING’ RIVERS: The Financial Times took a closer look at a “strange new force blighting the [Arctic] landscape”: rivers turning rust-orange due to global warming.

New science

- Lakes in the Congo Basin’s peatlands are releasing carbon that is thousands of years old | Nature Geoscience

- Natural non-forest ecosystems – such as grasslands and marshlands – were converted for agriculture at four times the rate of land with tree cover between 2005 and 2020 | Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- Around one-quarter of global tree-cover loss over 2001-22 was driven by cropland expansion, pastures and forest plantations for commodity production | Nature Food

In the diary

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean | Brasília

- 5 March: Nepal general elections

- 9-20 March: First part of the thirty-first session of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) | Kingston, Jamaica

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz.

Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

Greenhouse Gases

Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’

Rising temperatures across France since the mid-1970s is putting Tour de France competitors at “high risk”, according to new research.

The study, published in Scientific Reports, uses 50 years of climate data to calculate the potential heat stress that athletes have been exposed to across a dozen different locations during the world-famous cycling race.

The researchers find that both the severity and frequency of high-heat-stress events have increased across France over recent decades.

But, despite record-setting heatwaves in France, the heat-stress threshold for safe competition has rarely been breached in any particular city on the day the Tour passed through.

(This threshold was set out by cycling’s international governing body in 2024.)

However, the researchers add it is “only a question of time” until this occurs as average temperatures in France continue to rise.

The lead author of the study tells Carbon Brief that, while the race organisers have been fortunate to avoid major heat stress on race days so far, it will be “harder and harder to be lucky” as extreme heat becomes more common.

‘Iconic’

The Tour de France is one of the world’s most storied cycling races and the oldest of Europe’s three major multi-week cycling competitions, or Grand Tours.

Riders cover around 3,500 kilometres (km) of distance and gain up to nearly 55km of altitude over 21 stages, with only two or three rest days throughout the gruelling race.

The researchers selected the Tour de France because it is the “iconic bike race. It is the bike race of bike races,” says Dr Ivana Cvijanovic, a climate scientist at the French National Research Institute for Sustainable Development, who led the new work.

Heat has become a growing problem for the competition in recent years.

In 2022, Alexis Vuillermoz, a French competitor, collapsed at the finish line of the Tour’s ninth stage, leaving in an ambulance and subsequently pulling out of the race entirely.

Two years later, British cyclist Sir Mark Cavendish vomited on his bike during the first stage of the race after struggling with the 36C heat.

The Tour also makes a good case study because it is almost entirely held during the month of July and, while the route itself changes, there are many cities and stages that are repeated from year to year, Cvijanovic adds.

‘Have to be lucky’

The study focuses on the 50-year span between 1974 and 2023.

The researchers select six locations across the country that have commonly hosted the Tour, from the mountain pass of Col du Tourmalet, in the French Pyrenees, to the city of Paris – where the race finishes, along the Champs-Élysées.

These sites represent a broad range of climatic zones: Alpe d’ Huez, Bourdeaux, Col du Tourmalet, Nîmes, Paris and Toulouse.

For each location, they use meteorological reanalysis data from ERA5 and radiant temperature data from ERA5-HEAT to calculate the “wet-bulb globe temperature” (WBGT) for multiple times of day across the month of July each year.

WBGT is a heat-stress index that takes into account temperature, humidity, wind speed and direct sunlight.

Although there is “no exact scientific consensus” on the best heat-stress index to use, WBGT is “one of the rare indicators that has been originally developed based on the actual human response to heat”, Cvijanovic explains.

It is also the one that the International Cycling Union (UCI) – the world governing body for sport cycling – uses to assess risk. A WBGT of 28C or higher is classified as “high risk” by the group.

WBGT is the “gold standard” for assessing heat stress, says Dr Jessica Murfree, director of the ACCESS Research Laboratory and assistant professor at the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill.

Murfree, who was not involved in the new study, adds that the researchers are “doing the right things by conducting their science in alignment with the business practices that are already happening”.

The researchers find that across the 50-year time period, WBGT has been increasing across the entire country – albeit, at different rates. In the north-west of the country, WBGT has increased at an average rate of 0.1C per decade, while in the southern and eastern parts of the country, it has increased by more than 0.5C per decade.

The maps below show the maximum July WBGT for each decade of the analysis (rows) and for hourly increments of the late afternoon (columns). Lower temperatures are shown in lighter greens and yellows, while higher temperatures are shown in darker reds and purples.

Six Tour de France locations analysed in the study are shown as triangles on the maps (clockwise from top): Paris, Alpe d’ Huez, Nîmes, Toulouse, Col du Tourmalet and Bordeaux.

The maps show that the maximum WBGT temperature in the afternoon has surpassed 28C over almost the entire country in the last decade. The notable exceptions to this are the mountainous regions of the Alps and the Pyrenees.

The researchers also find that most of the country has crossed the 28C WBGT threshold – which they describe as “dangerous heat levels” – on at least one July day over the past decade. However, by looking at the WBGT on the day the Tour passed through any of these six locations, they find that the threshold has rarely been breached during the race itself.

For example, the research notes that, since 1974, Paris has seen a WBGT of 28C five times at 3pm in July – but that these events have “so far” not coincided with the cycling race.

The study states that it is “fortunate” that the Tour has so far avoided the worst of the heat-stress.

Cvijanovic says the organisers and competitors have been “lucky” to date. She adds:

“It has worked really well for them so far. But as the frequency of these [extreme heat] events is increasing, it will be harder and harder to be lucky.”

Dr Madeleine Orr, an assistant professor of sport ecology at the University of Toronto who was not involved in the study, tells Carbon Brief that the paper was “really well done”, noting that its “methods are good [and its] approach was sound”. She adds:

“[The Tour has] had athletes complain about [the heat]. They’ve had athletes collapse – and still those aren’t the worst conditions. I think that that says a lot about what we consider safe. They’ve still been lucky to not see what unsafe looks like, despite [the heat] having already had impacts.”

Heat safety protocols

In 2024, the UCI set out its first-ever high temperature protocol – a set of guidelines for race organisers to assess athletes’ risk of heat stress.

The assessment places the potential risk into one of five categories based on the WBGT, ranging from very low to high risk.

The protocol then sets out suggested actions to take in the event of extreme heat, ranging from having athletes complete their warm-ups using ice vests and cold towels to increasing the number of support vehicles providing water and ice.

If the WBGT climbs above the 28C mark, the protocol suggests that organisers modify the start time of the stage, adapt the course to remove particularly hazardous sections – or even cancel the race entirely.

However, Orr notes that many other parts of the race, such as spectator comfort and equipment functioning, may have lower temperatures thresholds that are not accounted for in the protocol, but should also be considered.

Murfree points out that the study’s findings – and the heat protocol itself – are “really focused on adaptation, rather than mitigation”. While this is “to be expected”, she tells Carbon Brief:

“Moving to earlier start times or adjusting the route specifically to avoid these locations that score higher in heat stress doesn’t stop the heat stress. These aren’t climate preventative measures. That, I think, would be a much more difficult conversation to have in the research because of the Tour de France’s intimate relationship with fossil-fuel companies.”

The post Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Dangerous heat for Tour de France riders only a ‘question of time’

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 20 February 2026: EU’s ‘3C’ warning | Endangerment repeal’s impact on US emissions | ‘Tree invasion’ fuelled South America’s fires

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Preparing for 3C

NEW ALERT: The EU’s climate advisory board urged countries to prepare for 3C of global warming, reported the Guardian. The outlet quoted Maarten van Aalst, a member of the advisory board, saying that adapting to this future is a “daunting task, but, at the same time, quite a doable task”. The board recommended the creation of “climate risk assessments and investments in protective measures”.

‘INSUFFICIENT’ ACTION: EFE Verde added that the advisory board said that the EU’s adaptation efforts were so far “insufficient, fragmented and reactive” and “belated”. Climate impacts are expected to weaken the bloc’s productivity, put pressure on public budgets and increase security risks, it added.

UNDERWATER: Meanwhile, France faced “unprecedented” flooding this week, reported Le Monde. The flooding has inundated houses, streets and fields and forced the evacuation of around 2,000 people, according to the outlet. The Guardian quoted Monique Barbut, minister for the ecological transition, saying: “People who follow climate issues have been warning us for a long time that events like this will happen more often…In fact, tomorrow has arrived.”

IEA ‘erases’ climate

MISSING PRIORITY: The US has “succeeded” in removing climate change from the main priorities of the International Energy Agency (IEA) during a “tense ministerial meeting” in Paris, reported Politico. It noted that climate change is not listed among the agency’s priorities in the “chair’s summary” released at the end of the two-day summit.

US INTERVENTION: Bloomberg said the meeting marked the first time in nine years the IEA failed to release a communique setting out a unified position on issues – opting instead for the chair’s summary. This came after US energy secretary Chris Wright gave the organisation a one-year deadline to “scrap its support of goals to reduce energy emissions to net-zero” – or risk losing the US as a member, according to Reuters.

Around the world

- ISLAND OBJECTION: The US is pressuring Vanuatu to withdraw a draft resolution supporting an International Court of Justice ruling on climate change, according to Al Jazeera.

- GREENLAND HEAT: The Associated Press reported that Greenland’s capital Nuuk had its hottest January since records began 109 years ago.

- CHINA PRIORITIES: China’s Energy Administration set out its five energy priorities for 2026-2030, including developing a renewable energy plan, said International Energy Net.

- AMAZON REPRIEVE: Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has continued to fall into early 2026, extending a downward trend, according to the latest satellite data covered by Mongabay.

- GEZANI DESTRUCTION: Reuters reported the aftermath of the Gezani cyclone, which ripped through Madagascar last week, leaving 59 dead and more than 16,000 displaced people.

20cm

The average rise in global sea levels since 1901, according to a Carbon Brief guest post on the challenges in projecting future rises.

Latest climate research

- Wildfire smoke poses negative impacts on organisms and ecosystems, such as health impacts on air-breathing animals, changes in forests’ carbon storage and coral mortality | Global Ecology and Conservation

- As climate change warms Antarctica throughout the century, the Weddell Sea could see the growth of species such as krill and fish and remain habitable for Emperor penguins | Nature Climate Change

- About 97% of South American lakes have recorded “significant warming” over the past four decades and are expected to experience rising temperatures and more frequent heatwaves | Climatic Change

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

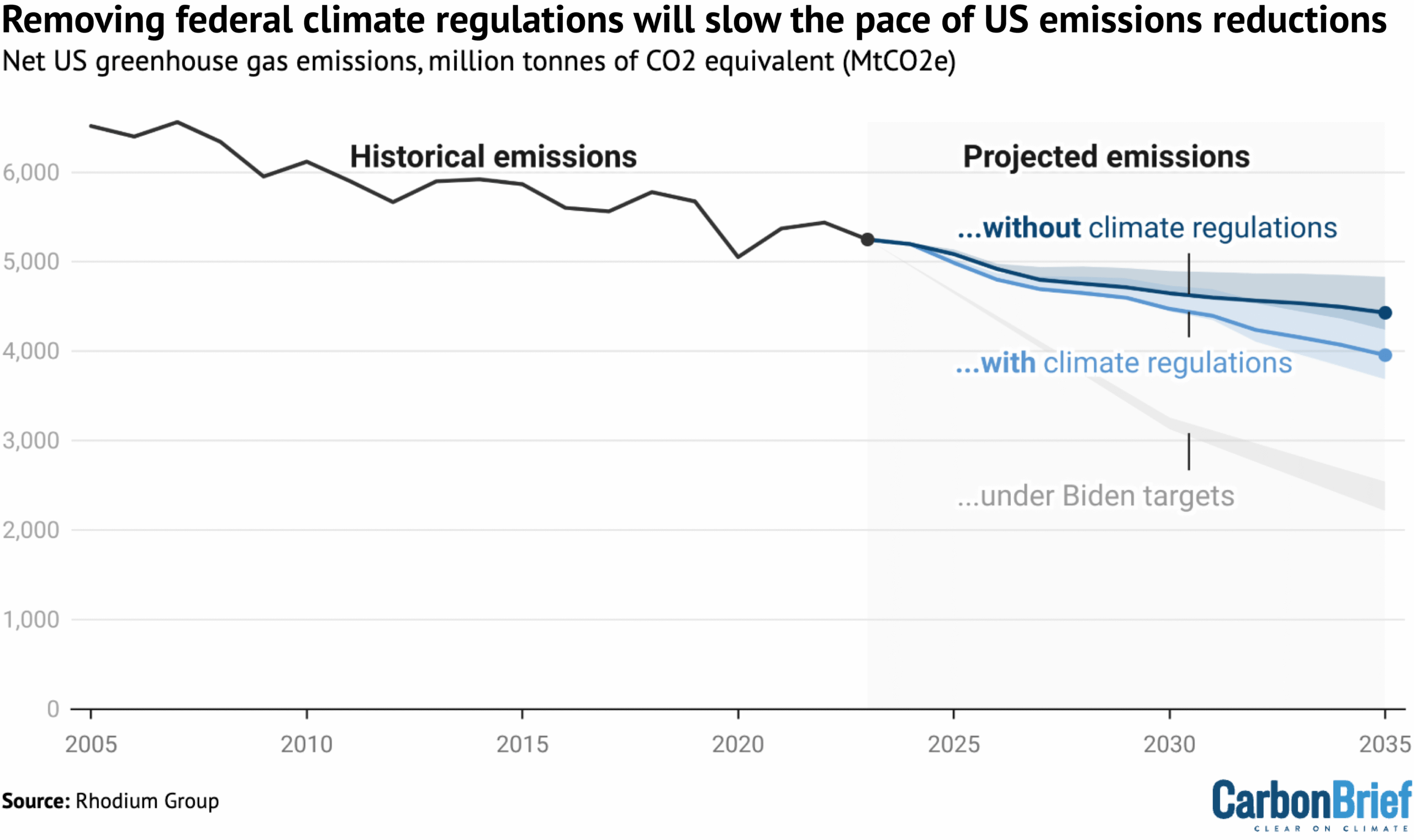

Repealing the US’s landmark “endangerment finding”, along with actions that rely on that finding, will slow the pace of US emissions cuts, according to Rhodium Group visualised by Carbon Brief. US president Donald Trump last week formally repealed the scientific finding that underpins federal regulations on greenhouse gas emissions, although the move is likely to face legal challenges. Data from the Rhodium Group, an independent research firm, shows that US emissions will drop more slowly without climate regulations. However, even with climate regulations, emissions are expected to drop much slower under Trump than under the previous Joe Biden administration, according to the analysis.

Spotlight

How a ‘tree invasion’ helped to fuel South America’s fires

This week, Carbon Brief explores how the “invasion” of non-native tree species helped to fan the flames of forest fires in Argentina and Chile earlier this year.

Since early January, Chile and Argentina have faced large-scale and deadly wildfires, including in Patagonia, which spans both countries.

These fires have been described as “some of the most significant and damaging in the region”, according to a World Weather Attribution (WWA) analysis covered by Carbon Brief.

In both countries, the fires destroyed vast areas of native forests and grasslands, displacing thousands of people. In Chile, the fires resulted in 23 deaths.

Multiple drivers contributed to the spread of the fires, including extended periods of high temperatures, low rainfall and abundant dry vegetation.

The WWA analysis concluded that human-caused climate change made these weather conditions at least three times more likely.

According to the researchers, another contributing factor was the invasion of non-native trees in the regions where the fires occurred.

The risk of non-native forests

In Argentina, the wildfires began on 6 January and persisted until the first week of February. They hit the city of Puerto Patriada and the Los Alerces and Lago Puelo national parks, in the Chubut province, as well as nearby regions.

In these areas, more than 45,000 hectares of native forests – such as Patagonian alerce tree, myrtle, coigüe and ñire – along with scrubland and grasslands, were consumed by the flames, according to the WWA study.

In Chile, forest fires occurred from 17 to 19 January in the Biobío, Ñuble and Araucanía regions.

The fires destroyed more than 40,000 hectares of forest and more than 20,000 hectares of non-native forest plantations, including eucalyptus and Monterey pine.

Dr Javier Grosfeld, a researcher at Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) in northern Patagonia, told Carbon Brief that these species, introduced to Patagonia for production purposes in the late 20th century, grow quickly and are highly flammable.

Because of this, their presence played a role in helping the fires to spread more quickly and grow larger.

However, that is no reason to “demonise” them, he stressed.

Forest management

For Grosfeld, the problem in northern Patagonia, Argentina, is a significant deficit in the management of forests and forest plantations.

This management should include pruning branches from their base and controlling the spread of non-native species, he added.

A similar situation is happening in Chile, where management of pine and eucalyptus plantations is not regulated. This means there are no “firebreaks” – gaps in vegetation – in place to prevent fire spread, Dr Gabriela Azócar, a researcher at the University of Chile’s Centre for Climate and Resilience Research (CR2), told Carbon Brief.

She noted that, although Mapuche Indigenous communities in central-south Chile are knowledgeable about native species and manage their forests, their insight and participation are not recognised in the country’s fire management and prevention policies.

Grosfeld stated:

“We are seeing the transformation of the Patagonian landscape from forest to scrubland in recent years. There is a lack of preventive forestry measures, as well as prevention and evacuation plans.”

Watch, read, listen

FUTURE FURNACE: A Guardian video explored the “unbearable experience of walking in a heatwave in the future”.

THE FUN SIDE: A Channel 4 News video covered a new wave of climate comedians who are using digital platforms such as TikTok to entertain and raise awareness.

ICE SECRETS: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast explored how scientists study ice cores to understand what the climate was like in ancient times and how to use them to inform climate projections.

Coming up

- 22-27 February: Ocean Sciences Meeting, Glasgow

- 24-26 February: Methane Mitigation Europe Summit 2026, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 25-27 February: World Sustainable Development Summit 2026, New Delhi, India

Pick of the jobs

- The Climate Reality Project, digital specialist | Salary: $60,000-$61,200. Location: Washington DC

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), science officer in the IPCC Working Group I Technical Support Unit | Salary: Unknown. Location: Gif-sur-Yvette, France

- Energy Transition Partnership, programme management intern | Salary: Unknown. Location: Bangkok, Thailand

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 20 February 2026: EU’s ‘3C’ warning | Endangerment repeal’s impact on US emissions | ‘Tree invasion’ fuelled South America’s fires appeared first on Carbon Brief.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits