Volcanic eruptions pose a fundamental challenge for scientists and their climate models.

It is well known that explosive eruptions can cause sudden cooling at the Earth’s surface and that multiple eruptions shape climate variability over decades and centuries.

When sulphur dioxide is injected into the stratosphere during an eruption, it forms aerosols that block sunlight from reaching the Earth’s surface.

Unlike human influences on climate change, which occur slowly and can be accounted for in climate models under a range of socioeconomic scenarios, the sporadic nature of volcanic eruptions poses a challenge for climate projections.

Scientists cannot currently forecast the occurrence of volcanic eruptions – including when and where they will occur and how much sulphur they will emit.

How, then, to account for the climate impact of volcanic eruptions when projecting into the future?

In a recent study, published in Communications Earth & Environment, we show that volcanic eruptions make a substantial contribution to the uncertainty in projections of global temperatures.

Our findings suggest that, when sporadic volcanic eruptions are included in climate projections, breaching of the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C warming limit is slightly delayed – but we will also see more decades with rapid rates of warming and cooling.

Volcanic forcing in climate projections

Climate scientists refer to the influence volcanic eruptions have on the climate – largely through the release of sulphur dioxide gas into the atmosphere – as “volcanic forcing”.

Current climate models apply a constant volcanic forcing value when running future projections. This value is calculated based on the historical average of forcings from 1850 to the present day.

This is the case with the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP), the international modelling effort that feeds into the influential assessment reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

However, this approach has significant limitations.

For starters, historically averaged forcing does not capture the episodic nature of eruptions.

Large-magnitude volcanic eruptions happen sporadically – sometimes clustering within decades and other times leaving century-long gaps between events.

Meanwhile, the reference period of 1850 to the present day has seen a relatively low frequency of large-magnitude eruptions that emitted more than 3 teragrams (Tg) of sulphur dioxide (SO2), when compared to multimillennial records.

Finally, volcanic forcing reconstructions used in earlier generations of CMIP climate models did not include small-to-moderate magnitude eruptions that emitted less than 3Tg of SO2.

This is because these eruptions went largely undetected before the satellite era began in 1980. Nonetheless, these smaller, but more frequent, eruptions contribute to 30-50% of long-term volcanic forcing.

Taking a new approach

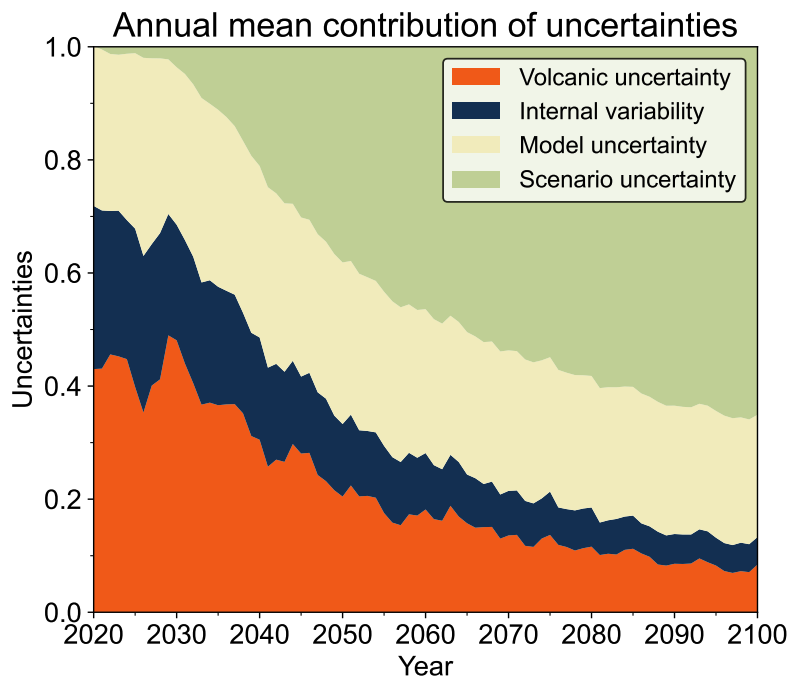

Traditionally, climate scientists have recognised three main sources of uncertainty in climate projections: internal variability, model uncertainty and scenario uncertainty.

Here, “internal” variability refers to natural fluctuations that are generated within the climate system, such as by El Niño; model uncertainty refers to the differences in the results between multiple climate models; and scenario uncertainty refers to the different ways that the world could develop over the decades to come.

Our results show that volcanic eruptions should be specifically considered as a fourth significant source of uncertainty in climate projections.

To explore how climate projections change when accounting for volcanic forcing uncertainty, our study uses a probabilistic approach that builds on a 2017 methodology developed by Bethke et al.

To do this, we develop “stochastic forcing scenarios” – essentially, 1,000 different plausible timelines of volcanic activity extending to the end of the century.

These scenarios draw from past volcanic activity recorded in ice cores going back 11,500 years, along with satellite measurements and geological evidence. Each scenario represents different combinations of eruption magnitudes, location, timing and frequency.

(In mathematics, “stochastic” systems involve randomness or uncertainty of outcome, making them unpredictable. This is in contrast to “deterministic” systems, which are characterised by having outcomes that are completely predictable based on initial conditions and a set of rules or equations.)

We then simulate climate projections using both stochastic and historically-averaged volcanic forcing between 2015 and 2100, exploring temperature rise under three different emissions scenarios drawn from the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs). These are a low-emission scenario (SSP1-1.9), an intermediate scenario that is in line with current climate policies(SSP2-4.5) and a very-high emissions scenario (SSP5-8.5).

For this step, we use a simple climate model, or “emulator”, called FaIR.

By simulating 1,000 different volcanic futures, we find that the climate uncertainty caused by future 21st century eruptions could exceed the internal variability of the climate system itself over the same period.

We also find that volcanic eruptions could account for more than one-third of total uncertainty in global temperature projections until the 2030s.

You can see these results in the plot below. It shows the contribution to the total uncertainty from the different sources. The colours represent volcanoes (orange), internal variability (dark blue), climate model response (yellow) and scenarios of future human emissions (green).

What this means for the 1.5C threshold

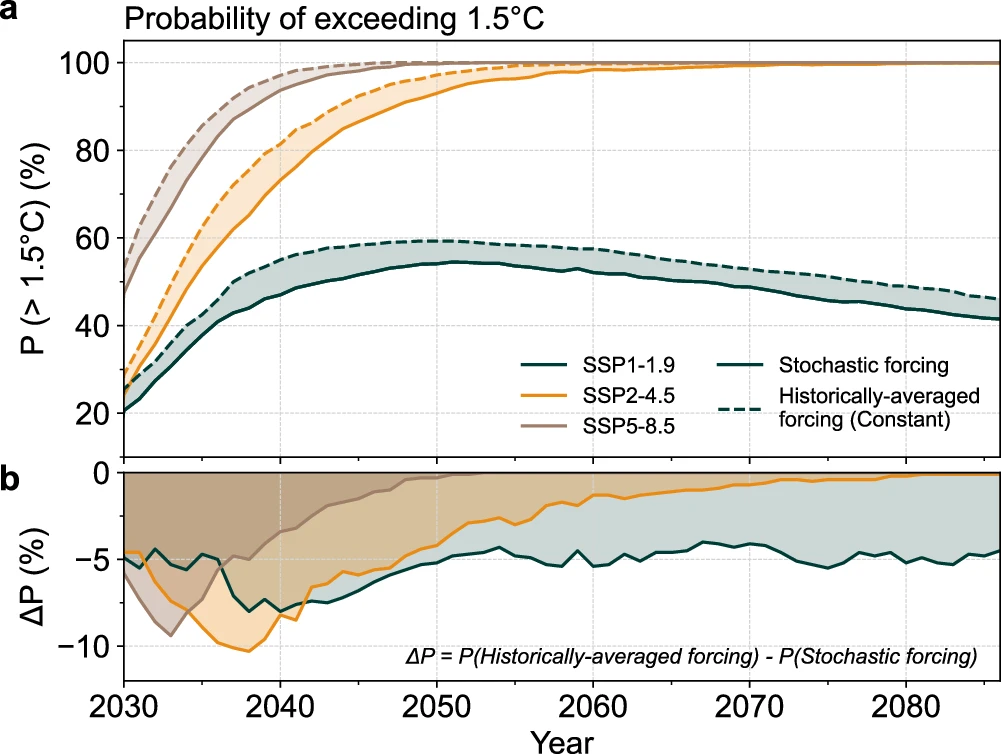

Our simulations demonstrate that incorporating possible timelines of volcanic activity slightly reduces the probability of crossing the Paris Agreement’s aspirational 1.5C temperature limit in the near term.

We find that – depending on the emissions scenario – the probability of exceeding 1.5C decreases by 4-10%, compared to projections using constant volcanic forcing.

While this might sound encouraging, future volcanic activity does not provide any long-term mitigation of human-caused warming.

The eruption of Mount Tambora in 1815 offers a dramatic illustration of this point. While the event cooled global temperatures by an average of 0.8C, it led to a “year without a summer” and caused crop failures and widespread famine across Europe, North America and China.

Eruptions produce temporary cooling lasting just a few years. They do not alter the underlying warming trend driven by human emissions.

Our study finds that, taking into account a range of future volcanic activity, global warming will still exceed 1.5C within decades under all but the very lowest emissions scenarios.

A high level of volcanic activity over the 21st century would help offset just a small fraction of global warming – meaning that emission reduction remains essential for meeting long-term climate goals.

The charts below show the probability of scenarios exceeding 1.5C using stochastic volcanic forcing (solid lines) and constant volcanic forcing (dashed lines) under three emissions scenarios (top) and the difference in probability between the two forcing approaches (bottom).

Decadal-scale temperature variability

Another important insight from our research is that extreme warm and cold decades become more likely once the variability of volcanic forcing is accounted for.

We find that the chance of a negative decadal trend – a decade where global surface temperature cools on average – increases by 10-18% under the intermediate emissions scenario.

We also find a corresponding increase in the probability of extremely warm decades, reflecting how volcanic forcing variability enhances the likelihood of both cooling and warming extremes.

This underscores how volcanic eruptions could introduce significant variability into the global temperature trends over decadal timescales.

Toward better climate projections

Understanding volcanic effects on the climate is essential for comprehensively assessing future risks to agriculture, infrastructure and energy systems.

Running thousands of volcanic scenarios with full-scale Earth system models is not practical as it requires too much computing power. On the other hand, current approaches have significant limitations, as described above.

However, there is a middle ground for future climate modelling efforts.

The next phase of future climate modelling experiments – the Scenario Model Intercomparison Project for CMIP7 – can use a more representative “average” volcanic forcing baseline that incorporates the effects of small eruptions often missed in historical records. This bias has now been addressed in the historical volcanic forcing dataset that will underpin the next generation of climate model simulations.

Additionally, modelling teams should run additional scenarios with high and low future volcanic activity to capture the range of volcanic uncertainty on climate projections.

While human-caused greenhouse gas emissions remain the dominant driver of climate change, properly accounting for volcanic uncertainty provides a more complete picture of possible climate futures and their implications for society.

The post Guest post: Investigating how volcanic eruptions can affect climate projections appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Guest post: Investigating how volcanic eruptions can affect climate projections

Climate Change

10 reasons why we need to act for the Amazon

The Amazon isn’t just the world’s greatest rainforest. She has been home to her original people for tens of thousands of years, who have persisted through centuries of colonial incursions to protect their home. At each moment of each day, the Amazon breathes, dances, and sings with an endless variety of plants and animals, many of those we humans have yet to understand. The Amazon is life-giving, irreplaceable and yet profoundly vulnerable.

Here are 10 fascinating facts to inspire you to take action for the Amazon:

1- The Amazon is the largest rainforest in the world

Spanning over nine countries in South America, the Amazon is the largest tropical forest on the planet, covering 6.7 million square kilometres. To put it in perspective, she is twice the size of India—the largest country in South Asia. The biggest part, around 60%, is in Brazil. After the Amazon, the Congo Basin and Papua host the world’s largest remaining rainforests.

2- The Amazon is one of the most biodiverse ecosystems on Earth

The Amazon is home to approximately 10% of all known species of fauna and flora worldwide. From the beautiful hyacinth macaws to fearless jaguars and the amazing pink dolphins, this vibrant ecosystem is teeming with life. In some areas, a single hectare can contain more than 300 tree species, approximately two-thirds of the native tree species in Europe (454), making the Amazon one of the most botanically rich regions on Earth.

Studies show that the Amazon Basin harbours at least 2,716 species of fish, 427 amphibians, 371 reptiles, 1,300 birds, and 425 mammals. However, the vast majority of its biodiversity lies in her invertebrates, particularly insects, with over 2.5 million species currently known

3- There are approximately 3 million Indigenous People living in the Amazon

The Amazon is home to a diverse group of Indigenous Peoples. Over 390 Indigenous Peoples live in the region, along with approximately 137 isolated groups, who have chosen to remain uncontacted.

In Brazil, about 51.2% of the country’s Indigenous population resides in the Amazon. But the largest tropical forest in the world is also home to traditional communities that have lived in harmony with the forest for generations, such as Rubber Tappers, Ribeirinhos—who inhabit the Amazon’s riverbanks—and Quilombolas, Afro-Brazilian communities descended from enslaved people..

4- The Amazon is home to over 40 million people

The Amazon is not just a vast rainforest rich in biodiversity and home to Indigenous People—it is also home to several cities. In Brazil, These include Manaus , an industrial hub with a population of 2.2 million, and Belém , which will host the United Nations Climate Conference (COP30) in November 2025.

These people’s lives are intrinsically connected to the forest. They depend on her for their food, fresh water, and to regulate the local climate. Smoke from the fires in the Amazon directly impacts the people living in the region, darkening the skies and causing respiratory problems to the population, especially children and elders.

5- The Amazon is vital for the global climate

The Amazon is estimated to store about 123 billion tons of carbon, both above and below ground, making her one of Earth’s most crucial “carbon reserves”, vital in the fight against the climate crisis. However, studies show that fire- and deforestation-affected areas of the Amazon are now releasing more CO₂ into the atmosphere than they absorb. This poses a major threat to the global climate. Protecting the Amazon means protecting the future of everyone.

6- Fires in the Amazon are not natural

Unlike bushfires in Australia and other parts of the world, fires in the Amazon are not natural. In the Amazon biome, fire is used in the deforestation process to clear the land for agriculture and pasture. The use of fire in the Amazon is often illegal, and so is deforestation. This practice has a major impact on the local biodiversity, the health of the populations living in the region, and to the global climate, as the fires release vast amounts of carbon into the atmosphere.

© Victor Moriyama / Amazônia em Chamas

7- Cattle ranching is the leading cause of deforestation in the Amazon

The expansion of agribusiness in the Amazon is putting more and more pressure on the forest. According to a study, 90% of the deforested areas in the Brazilian Amazon are turned into pasture to produce meat and dairy. This means the food we eat may be linked to deforestation in the Amazon. We must urge our governments to stop buying from forest destroyers and ensure supply chains are free from deforestation, and demand stronger protections for the Amazon.

8- Illegal gold mining is a major threat to Indigenous Peoples

Illegal gold mining in Indigenous Lands in Brazil surged by 265% in just five years, between 2018 and 2022. The activity poses a severe threat to the health and the lives of Indigenous People, destroying rivers, contaminating communities with mercury and bringing violence and death to their territories.

But illegal gold mining doesn’t impact just the forest and Indigenous People. A recent study showed that mercury-contaminated fish are being sold in markets in major Amazonian cities, putting the health of millions at risk.

9- The Amazon is close to a point of no return

About 17% of the Amazon has already been deforested, and scientists warn we are getting dangerously close to a ‘point of no return’.

According to a study, if we lose between 20% and 25% of the Amazon, the forest might lose its ability to generate its own moisture, leading to reduced rainfall, higher temperatures, and a self-reinforcing cycle of drying and degradation.

As a result, vast areas of the forest could turn into a drier, savanna-like ecosystem, unable to sustain her rich biodiversity. This could have catastrophic consequences for the global climate, local communities, and the planet’s ecological balance.

10- The most important Climate Conference in the world is happening in the Amazon this year

COP30, the United Nations Climate Conference, will take place in Belém, the second largest city in the Amazon region, in November 2025. During the conference, representatives from countries all over the world will meet to discuss measures to protect the climate. Across the globe, we are already witnessing and feeling the impacts of the climate crisis. This is our chance to demand our political leaders move beyond words to urgent action. They must stop granting permission and public funds to Earth-destroying industries. Instead, our leaders must respect, pursue, and support real solutions that already exist—solutions that put the forest and her people at the heart of the response. Indigenous guardians of the forest hold true authority, and they must be respected and heard. The moment is now.

We are the turning point! Join the movement and demand respect for the Amazon.

Climate Change

As the Data Center Boom Ramps Up in the Rural Midwest, What Should Communities Expect?

The rapid development will change the Corn Belt in significant, unforeseen ways. Residents are just beginning to grapple with what that means.

TAZEWELL COUNTY, Ill.—To the untrained eye, Central Illinois is all lush fields of corn and green soybeans shortly before harvest. The wind shuffles through the row crops, and the air is warm and humid and full of insects. The horizon is dotted with power lines, strung together by wire, and the occasional water tower—the only objects that disrupt a vast sky.

As the Data Center Boom Ramps Up in the Rural Midwest, What Should Communities Expect?

Climate Change

Why Billions of Gallons of Raw Sewage Keep Ending up in Philadelphia Waterways

With a new analysis showing where the pollution is going, environmental advocates call on public officials to do more to stop it.

PHILADELPHIA—Some 280 years after a river-swimming Benjamin Franklin petitioned to curb water pollution here, the city is still struggling to meet the challenge, according to water advocates who assembled along the banks of one of its two main rivers on Monday.

Why Billions of Gallons of Raw Sewage Keep Ending up in Philadelphia Waterways

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change3 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Greenhouse Gases1 year ago

Greenhouse Gases1 year ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Greenhouse Gases3 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change1 year ago

Climate Change1 year ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Renewable Energy4 months ago

US Grid Strain, Possible Allete Sale