We can’t control how we enter this world. We can’t choose where we are born, or who births us.

And yet so many of us take great pride in where we are from — maybe that means where we were born, or where we grew up. I am grateful for both of those places. I was born in Lima, Perú, adopted as a baby, and grew up in Saint Paul, Minnesota. From the very beginning, my worldview was a wide one, because I was raised with the knowledge that I was from two very separate places and that was something to celebrate.

My childhood was spent in Saint Paul, and as an adult I have made my way back. When I think of Saint Paul, I think of going to school with my sisters, crunchy fall leaves and freezing Halloween nights, snow days and tornado drills, and endless summers spent swimming in Minnesota lakes.

I am so glad to have spent time in my birth country. Studying abroad, traveling, and working in Perú has been a gift. When I think of Lima, I think of cloudy winter days and a blue-green ocean. I think of chicha morada (warm purple corn drinks) and buying snacks on the Metro line. I think of running on the coast in the sunshine of summertime, watching people surf, and fruit vendors sell.

When I think of my hometown of Saint Paul, I can’t help but think of the highway. Less than a mile from where I grew up, I-94 cuts across the Rondo neighborhood. In the 1950s and 60s, the construction of I-94 split the vibrant Rondo neighborhood in two. According to the MN Historical Society, one in eight African Americans in St.Paul lost their home to the new I-94. A tale as old as time, this story has repeated itself across the United States — governments using modern infrastructure to divide diverse communities.

Thirty years later, my parents and community members kept the neighborhood’s memory alive through stories. They helped us understand that we were living next to a community that had gone through immense challenge and change.

When I think of my birth city of Lima, I can’t help but think of the wall.

In the capital city of Perú, el Muro de la Vergüenza, or Wall of Shame, is a physical barrier between the districts of La Molina and Villa Maria del Triunfo. These two districts share a hill on the east side of the city. The wall provides a stark contrast between the districts of La Molina and Surco, with a high socioeconomic status, and the districts of San Juan de Miraflores and Villa María del Triunfo, with a low one. Houses with sprawling lawns, swimming pools, and paved streets are set apart from homes made with sheets of metal and wood, dirt roads and no running water. The Wall has been a subject of books, movies, and community conversation.

While some argue that the wall is a right for private property owners, many see the wall as an enforcement of class divide.

To add another layer to the story, the housing on the hills intercepts the lomas, or fog oases. This beautiful and rare plant formation can be found in Perú and northern Chile. In the foggy winter months, the coastal deserts are covered in rich vegetation including many endemic species. The natural landscape and communities have suffered as instances of invasion and land trafficking have occurred in the area, urbanization continues to swell the population, and climate change disrupts the fragile ecosystem.

We can’t control how we enter this world. We can’t choose where we are born, or who births us. And yet so many of us take great pride in where we are from.

In the recent year I have been glad to see efforts to improve the infrastructure that is dividing the communities I love. The bridge that crossed I-94 near my home went under construction and is back in operation with larger sidewalks to try to facilitate more pedestrian movement from both sides of the highway. This year, parts of the Wall of Shame were destroyed in Lima following an order from the Constitutional Court.

There are local efforts to conserve the lomas in Perú, including community groups educating the public on the importance of the plant formations and advocating for local government to protect the land. Additionally, the construction of protective pathways and fog catchers to provide as much water as possible to the plants. Despite these changes, the division and damage still remain.

We can’t control how we enter this world; what side of the highway or the wall we exist on. I grew up being taught that I was connected to these different places, and that I should be proud. I care about climate change because I care about myself and I care about you. This is my climate story. We are all connected. Right?

So it was confusing to me to learn and see ways that modern infrastructure is dividing people instead of connecting us. Historically and contemporarily, we as people have access to so much knowledge and so many tools that should be able to help us collaborate and create a healthy world.

But I have learned that there are far too many examples of self-betrayal — actions that ultimately hurt others and ourselves. What if we use modern technology and prior knowledge to take care of our planet, instead of dividing us? To best care for the planet, I am excited to learn, grow, and act. I am excited to be able to facilitate learning, growth, and actions with my students. Why don’t we all do that together?

Sofía Cerkvenik is a social studies educator and sports equity activist in Saint Paul. Sofía was adopted from Lima, Perú and grew up in Saint Paul, Minnesota. She received her B.A. in History with a minor in Asian Languages and Literatures and her M.Ed in Social Studies with an emphasis on Social Justice at the University of Minnesota. Sofía believes that exploring various windows and mirrors in the classroom is imperative to establish greater understanding, empathy, and action among students. Sofía has had an opportunity to do just that through various study abroad experiences including the US Department of State’s Critical Language Scholarship Program, participating once in Dalian, China and once in Changchun, China, as a Fulbright Research Scholar in 2022, and this winter as a COP28 delegate.

Sofía is a Climate Generation Window Into COP delegate for COP28. To learn more, we encourage you to meet the full delegation and subscribe to the Window Into COP digest.

The post A Road and A Wall appeared first on Climate Generation.

Climate Change

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

The country’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas benefited from what critics say is a questionable IRS interpretation of tax credits.

Cheniere Energy, the largest producer and exporter of U.S. liquefied natural gas, received $370 million from the IRS in the first quarter of 2026, a payout that shipping experts, tax specialists and a U.S. senator say the company never should have received.

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

Climate Change

DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Absolute State of the Union

‘DRILL, BABY’: US president Donald Trump “doubled down on his ‘drill, baby, drill’ agenda” in his State of the Union (SOTU) address, said the Los Angeles Times. He “tout[ed] his support of the fossil-fuel industry and renew[ed] his focus on electricity affordability”, reported the Financial Times. Trump also attacked the “green new scam”, noted Carbon Brief’s SOTU tracker.

COAL REPRIEVE: Earlier in the week, the Trump administration had watered down limits on mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants, reported the Financial Times. It remains “unclear” if this will be enough to prevent the decline of coal power, said Bloomberg, in the face of lower-cost gas and renewables. Reuters noted that US coal plants are “ageing”.

OIL STAY: The US Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments brought by the oil industry in a “major lawsuit”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper said the firms are attempting to head off dozens of other lawsuits at state level, relating to their role in global warming.

SHIP-SHILLING: The Trump administration is working to “kill” a global carbon levy on shipping “permanently”, reported Politico, after succeeding in delaying the measure late last year. The Guardian said US “bullying” could be “paying off”, after Panama signalled it was reversing its support for the levy in a proposal submitted to the UN shipping body.

Around the world

- RARE EARTHS: The governments of Brazil and India signed a deal on rare earths, said the Times of India, as well as agreeing to collaborate on renewable energy.

- HEAT ROLLBACK: German homes will be allowed to continue installing gas and oil heating, under watered-down government plans covered by Clean Energy Wire.

- BRAZIL FLOODS: At least 53 people died in floods in the state of Minas Gerais, after some areas saw 170mm of rain in a few hours, reported CNN Brasil.

- ITALY’S ATTACK: Italy is calling for the EU to “suspend” its emissions trading system (ETS) ahead of a review later this year, said Politico.

- COOKSTOVE CREDITS: The first-ever carbon credits under the Paris Agreement have been issued to a cookstove project in Myanmar, said Climate Home News.

- SAUDI SOLAR: Turkey has signed a “major” solar deal that will see Saudi firm ACWA building 2 gigawatts in the country, according to Agence France-Presse.

$467 billion

The profits made by five major oil firms since prices spiked following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine four years ago, according to a report by Global Witness covered by BusinessGreen.

Latest climate research

- Claims about the “fingerprint” of human-caused climate change, made in a recent US Department of Energy report, are “factually incorrect” | AGU Advances

- Large lakes in the Congo Basin are releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere from “immense ancient stores” | Nature Geoscience

- Shared Socioeconomic Pathways – scenarios used regularly in climate modelling – underrepresent “narratives explicitly centring on democratic principles such as participation, accountability and justice” | npj Climate Action

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

The constituency of Richard Tice MP, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of Reform UK, is the second-largest recipient of flood defence spending in England, according to new Carbon Brief analysis. Overall, the funding is disproportionately targeted at coastal and urban areas, many of which have Conservative or Liberal Democrat MPs.

Spotlight

Is there really a UK ‘greenlash’?

This week, after a historic Green Party byelection win, Carbon Brief looks at whether there really is a “greenlash” against climate policy in the UK.

Over the past year, the UK’s political consensus on climate change has been shattered.

Yet despite a sharp turn against climate action among right-wing politicians and right-leaning media outlets, UK public support for climate action remains strong.

Prof Federica Genovese, who studies climate politics at the University of Oxford, told Carbon Brief:

“The current ‘war’ on green policy is mostly driven by media and political elites, not by the public.”

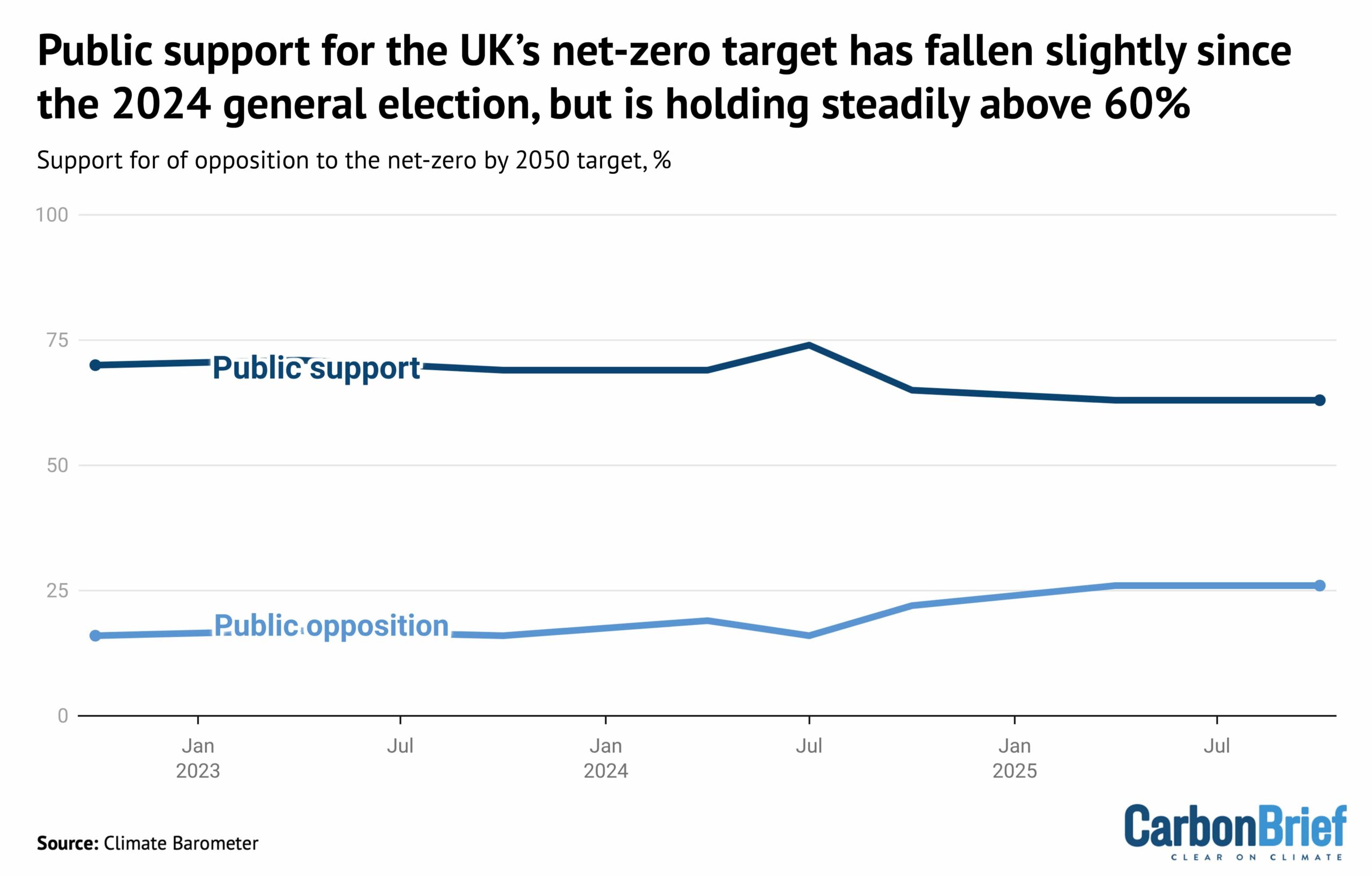

Indeed, there is still a greater than two-to-one majority among the UK public in favour of the country’s legally binding target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, as shown below.

Steve Akehurst, director of public-opinion research initiative Persuasion UK, also noted the growing divide between the public and “elites”. He told Carbon Brief:

“The biggest movement is, without doubt, in media and elite opinion. There is a bit more polarisation and opposition [to climate action] among voters, but it’s typically no more than 20-25% and mostly confined within core Reform voters.”

Conservative gear shift

For decades, the UK had enjoyed strong, cross-party political support for climate action.

Lord Deben, the Conservative peer and former chair of the Climate Change Committee, told Carbon Brief that the UK’s landmark 2008 Climate Change Act had been born of this cross-party consensus, saying “all parties supported it”.

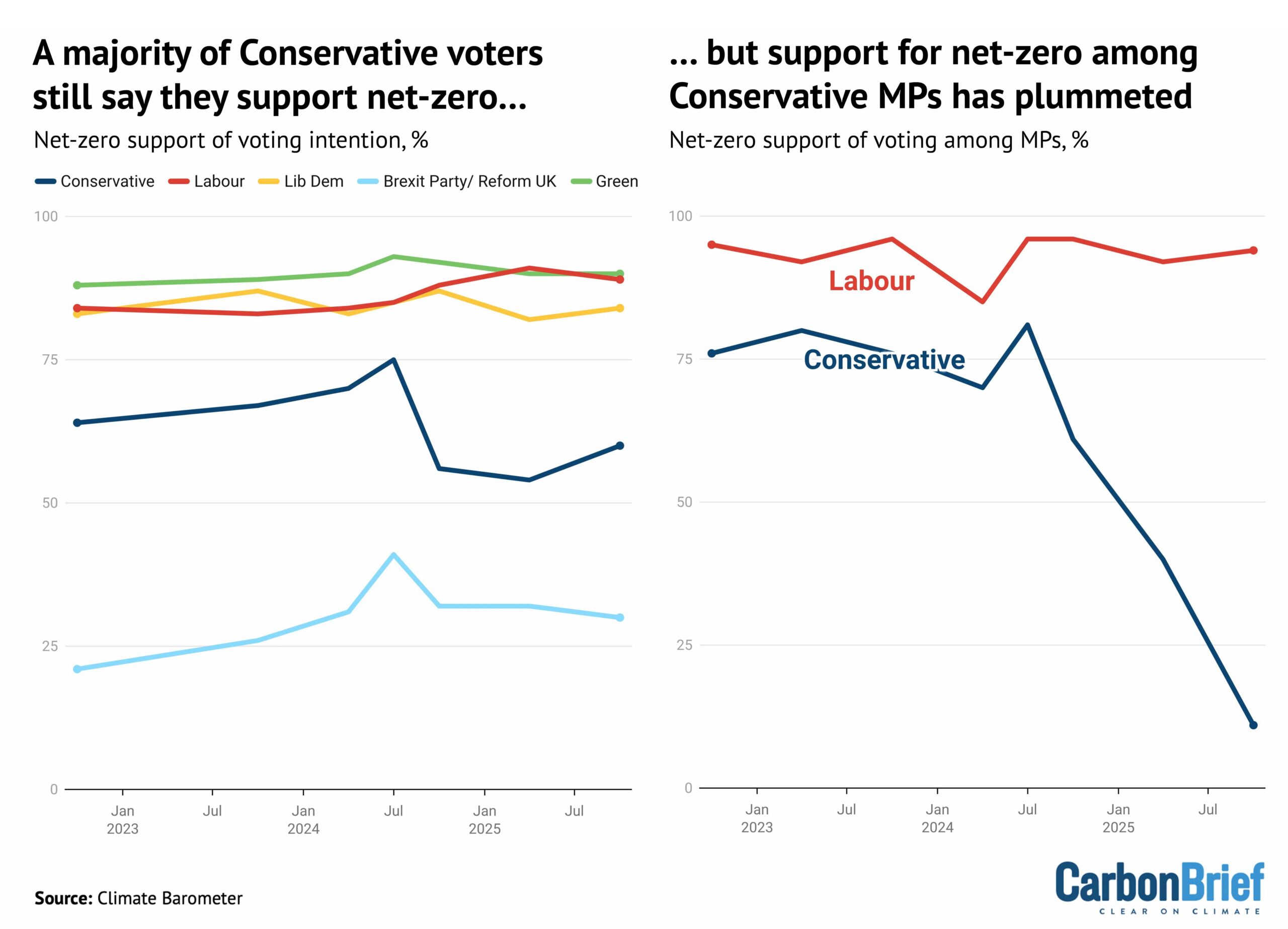

Since their landslide loss at the 2024 election, however, the Conservatives have turned against the UK’s target of net-zero emissions by 2050, which they legislated for in 2019.

Curiously, while opposition to net-zero has surged among Conservative MPs, there is majority support for the target among those that plan to vote for the party, as shown below.

Dr Adam Corner, advisor to the Climate Barometer initiative that tracks public opinion on climate change, told Carbon Brief that those who currently plan to vote Reform are the only segment who “tend to be more opposed to net-zero goals”. He said:

“Despite the rise in hostile media coverage and the collapse of the political consensus, we find that public support for the net-zero by 2050 target is plateauing – not plummeting.”

Reform, which rejects the scientific evidence on global warming and campaigns against net-zero, has been leading the polls for a year. (However, it was comfortably beaten by the Greens in yesterday’s Gorton and Denton byelection.)

Corner acknowledged that “some of the anti-net zero noise…[is] showing up in our data”, adding:

“We see rising concerns about the near-term costs of policies and an uptick in people [falsely] attributing high energy bills to climate initiatives.”

But Akehurst said that, rather than a big fall in public support, there had been a drop in the “salience” of climate action:

“So many other issues [are] competing for their attention.”

UK newspapers published more editorials opposing climate action than supporting it for the first time on record in 2025, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Global ‘greenlash’?

All of this sits against a challenging global backdrop, in which US president Donald Trump has been repeating climate-sceptic talking points and rolling back related policy.

At the same time, prominent figures have been calling for a change in climate strategy, sold variously as a “reset”, a “pivot”, as “realism”, or as “pragmatism”.

Genovese said that “far-right leaders have succeeded in the past 10 years in capturing net-zero as a poster child of things they are ‘fighting against’”.

She added that “much of this is fodder for conservative media and this whole ecosystem is essentially driving what we call the ‘greenlash’”.

Corner said the “disconnect” between elite views and the wider public “can create problems” – for example, “MPs consistently underestimate support for renewables”. He added:

“There is clearly a risk that the public starts to disengage too, if not enough positive voices are countering the negative ones.”

Watch, read, listen

TRUMP’S ‘PETROSTATE’: The US is becoming a “petrostate” that will be “sicker and poorer”, wrote Financial Times associate editor Rana Forohaar.

RHETORIC VS REALITY: Despite a “political mood [that] has darkened”, there is “more green stuff being installed than ever”, said New York Times columnist David Wallace-Wells.

CHINA’S ‘REVOLUTION’: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast reported from China on the “green energy revolution” taking place in the country.

Coming up

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean, Brasília

- 3 March: UK spring statement

- 4-11 March: China’s “two sessions”

- 5 March: Nepal elections

Pick of the jobs

- The Guardian, senior reporter, climate justice | Salary: $123,000-$135,000. Location: New York or Washington DC

- China-Global South Project, non-resident fellow, climate change | Salary: Up to $1,000 a month. Location: Remote

- University of East Anglia, PhD in mobilising community-based climate action through co-designed sports and wellbeing interventions | Salary: Stipend (unknown amount). Location: Norwich, UK

- TABLE and the University of São Paulo, Brazil, postdoctoral researcher in food system narratives | Salary: Unknown. Location: Pirassununga, Brazil

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

Seven Pacific island nations say they will demand heftier levies on global shipping emissions if opponents of a green deal for the industry succeed in reopening negotiations on the stalled accord.

The United States and Saudi Arabia persuaded countries not to grant final approval to the International Maritime Organization’s Net-Zero Framework (NZF) in October and they are now leading a drive for changes to the deal.

In a joint submission seen by Climate Home News, the seven climate-vulnerable Pacific countries said the framework was already a “fragile compromise”, and vowed to push for a universal levy on all ship emissions, as well as higher fees . The deal currently stipulates that fees will be charged when a vessel’s emissions exceed a certain level.

“For many countries, the NZF represents the absolute limit of what they can accept,” said the unpublished submission by Fiji, Kiribati, Vanuatu, Nauru, Palau, Tuvalu and the Solomon Islands.

The countries said a universal levy and higher charges on shipping would raise more funds to enable a “just and equitable transition leaving no country behind”. They added, however, that “despite its many shortcomings”, the framework should be adopted later this year.

US allies want exemption for ‘transition fuels’

The previous attempt to adopt the framework failed after governments narrowly voted to postpone it by a year. Ahead of the vote, the US threatened governments and their officials with sanctions, tariffs and visa restrictions – and President Donald Trump called the framework a “Green New Scam Tax on Shipping”.

Since then, Liberia – an African nation with a major low-tax shipping registry headquartered in the US state of Virginia – has proposed a new measure under which, rather than staying fixed under the NZF, ships’ emissions intensity targets change depending on “demonstrated uptake” of both “low-carbon and zero-carbon fuels”.

The proposal places stringent conditions on what fuels are taken into consideration when setting these targets, stressing that the low- and zero-carbon fuels should be “scalable”, not cost more than 15% more than standard marine fuels and should be available at “sufficient ports worldwide”.

This proposal would not “penalise transitional fuels” like natural gas and biofuels, they said. In the last decade, the US has built a host of large liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals, which the Trump administration is lobbying other countries to purchase from.

The draft motion, seen by Climate Home News, was co-sponsored by US ally Argentina and also by Panama, a shipping hub whose canal the US has threatened to annex. Both countries voted with the US to postpone the last vote on adopting the framework.

The IMO’s Panamanian head Arsenio Dominguez told reporters in January that changes to the framework were now possible.

“It is clear from what happened last year that we need to look into the concerns that have been expressed [and] … make sure that they are somehow addressed within the framework,” he said.

Patchwork of levies

While the European Union pushed firmly for the framework’s adoption, two of its shipping-reliant member states – Greece and Cyprus – abstained in October’s vote.

After a meeting between the Greek shipping minister and Saudi Arabia’s energy minister in January, Greece said a “common position” united Greece, Saudi Arabia and the US on the framework.

If the NZF or a similar instrument is not adopted, the IMO has warned that there will be a patchwork of differing regional levies on pollution – like the EU’s emissions trading system for ships visiting its ports – which will be complicated and expensive to comply with.

This would mean that only countries with their own levies and with lots of ships visiting their ports would raise funds, making it harder for other nations to fund green investments in their ports, seafarers and shipping companies. In contrast, under the NZF, revenues would be disbursed by the IMO to all nations based on set criteria.

Anais Rios, shipping policy officer from green campaign group Seas At Risk, told Climate Home News the proposal by the Pacific nations for a levy on all shipping emissions – not just those above a certain threshold – was “the most credible way to meet the IMO’s climate goals”.

“With geopolitics reframing climate policy, asking the IMO to reopen the discussion on the universal levy is the only way to decarbonise shipping whilst bringing revenue to manage impacts fairly,” Rios said.

“It is […] far stronger than the Net-Zero Framework that is currently on offer.”

The post Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen appeared first on Climate Home News.

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits