The retreat of sea ice in the Arctic has long been a prominent symbol of climate change.

Observations reveal that Arctic sea ice extent at the end of summer has halved, since satellite records began in the late 1970s.

Yet, since the late 2000s, the pace of Arctic sea ice loss has slowed markedly, with no statistically significant decline for about 20 years.

In new research, published in Geophysical Research Letters, my colleagues and I explore the reasons for the recent slowdown of Arctic sea ice – and turn to climate models to understand what might happen next.

Our findings show that, rather than being an unexpected or rare event, climate model simulations suggest we should expect periods like this to occur relatively frequently.

This current slowdown is likely caused by natural fluctuations of the climate system – just as they played a part in an acceleration of sea ice loss in the decades prior.

Were it not for human-caused warming, it is likely that sea ice would have increased over this period.

According to our simulations, the slowdown could even last for another five or 10 years – even as the world continues to warm.

Widespread slowdown

The changes in the Arctic are one of the most clear and well-known indicators of a warming climate.

With the Arctic warming up to four times the rate of the global average, the region has lost more than 10,000 cubic kilometres of sea ice since the 1980s. (The volume of ice lost is roughly equivalent to 4bn Olympic swimming pools).

Arctic sea ice reached its smallest extent on record in September 2012, dwindling to 3.41m square kilometres (km2). This triggered discussions of when the Arctic might see its first “ice-free” summer, where sea ice extent drops below 1m km2.

Research has shown that human-caused warming is responsible for up to two-thirds of this decline, with the remainder down to natural fluctuations in the climate system, also known as “internal climate variability”.

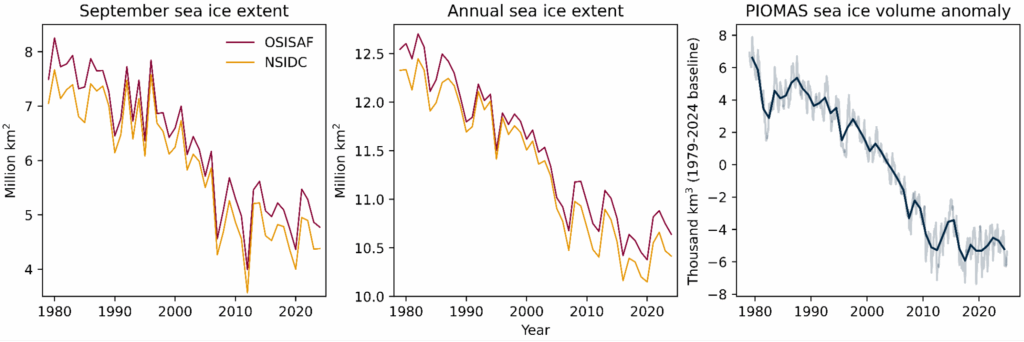

Despite the record low of 2012, satellite data reveals a widespread slowdown in Arctic sea ice loss over the past two decades.

Climate model simulations of Arctic sea ice thickness and volume further reinforce these observations, indicating little or no significant decline over the past 15 years.

This data is laid out in the charts below, which show average sea ice extent in September (left) and for the whole year (middle), as well as how annual average sea ice volume differs from the long-term average (right).

(September is typically the point in the year where sea ice reaches its annual minimum, at the end of the Arctic summer.)

The coloured lines indicate that the data originates from the National Snow and Ice Data Centre (NSIDC, orange), the Ocean and Sea Ice Satellite Application Facility (OSISAF, red) and the Pan-Arctic Ice Ocean Modeling and Assimilation System (PIOMAS, blue).

These observational records show how the precipitous decline in sea ice seen over much of the satellite data has slowed since the late 2000s.

It also shows that the slowdown is not limited to summer months, but is occurring year-round.

Our study is not the first to highlight this slowdown – several recent studies have also examined various aspects of this phenomenon. Meanwhile, a 2015 paper was remarkably prescient in suggesting such a slowdown could occur.

Is the slowdown surprising?

The loss of sea ice around the north pole is both a cause and effect of Arctic amplification – the term given to the rapid warming in the region.

Melting snow and ice reduces the reflectiveness, or “albedo”, of the Arctic’s surface, meaning less incoming sunlight is reflected back out to space. This causes greater warming and even more melting of ice and snow.

This “surface-albedo feedback” is one of several drivers of Arctic amplification.

Given global warming is caused by the continued rise in greenhouse gas emissions, it might seem puzzling – or even impossible – that Arctic sea ice loss could slow down.

However, the recent generations of climate models used for the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project (CMIP) – the international modelling effort that feeds into the influential reports from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) – illustrate why this might be happening.

Models from CMIP5 and CMIP6, which simulate the historical period and explore different future warming scenarios, indicate that slowdowns in Arctic sea ice loss lasting multiple decades are relatively common – happening in roughly 20% of model runs.

This is due to natural variability in the climate system, which can temporarily counteract decline of sea ice – even under high-emission scenarios.

One way that climate scientists investigate natural variability is by running multiple simulations of a model, each with identical levels of human-caused emissions of carbon dioxide, aerosols and methane. These are known as “ensembles”.

Due to the chaotic nature of the climate system, which results in different phases of natural variability, the different model runs produce different outcomes – even if the long-term climate change signal from human activity remains constant.

Large ensembles help us to understand how to interpret the Earth’s observed climate record, which has been influenced by both human-induced climate change and natural variations.

In our research, we examine how many individual model runs within the ensemble exhibit a similar or greater slowdown in sea ice loss than the observed record over 2005-24.

The models show that natural climate variability can accelerate sea ice loss, as seen during the dramatic record-lows in 2007 and 2012. However, this natural variability can also temporarily slow the longer-term downward trend.

The primary suspects behind this multi-decade variability are natural fluctuations linked to the tropical Pacific and the North Atlantic, although the precise causes are yet to be quantified.

For example, a shift from the positive, warm phase to the negative, cool phase of a natural cycle in the Interdecadal Pacific Oscillation is associated with bringing much cooler waters close to the North American coastline and into the Arctic. This could potentially lead to sea ice growth.

What might happen to Arctic sea ice cover next?

So how long could this current slowdown persist?

Climate model simulations suggest the current slowdown might continue for another five or 10 years.

However, there is an important caveat: slowdowns like this often set the stage for faster declines later.

Climate models suggest that when the slowdown inevitably ends, the rate of sea ice loss could rapidly accelerate.

Thousands of simulations analysed in our research reveal that September sea ice loss ramps up at a rate of more than 500,000km2 per decade after prolonged periods of minimal sea ice loss.

This would equate to more than 10% of current sea ice cover in September.

An analogy of Arctic sea ice extent behaving like a ball bouncing downhill – set out in a 2015 Carbon Brief article by Prof Ed Hawkins – is particularly apt here.

Just like the ball – which eventually reaches the bottom due to gravity, despite an erratic journey – Arctic sea ice loss may temporarily seem to defy expectations at present.

Ultimately, however, sea ice loss will resume, reflecting the underlying human-induced warming trend.

While it may seem contradictory that Arctic sea ice loss can slow even as global temperatures climb, climate models clearly show that such periods are expected parts of climate variability.

As a result, the recent slowdown in Arctic sea ice does not signal an end to climate change or lessen the urgency of cutting greenhouse gas emissions, if global goals are to be met.

While the current slowdown might persist for some years to come, when sea ice loss resumes, it could do so with renewed intensity.

The post Guest post: Why the recent slowdown in Arctic sea ice loss is only temporary appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Guest post: Why the recent slowdown in Arctic sea ice loss is only temporary

Climate Change

How Sumatra’s lost trees turned extreme rain into catastrophe

Ronny P Sasmita is a senior analyst at Indonesia Strategic and Economics Action Institution, a think-tank specialising in geopolitical and geoeconomic studies in Indonesia.

The devastation that has swept across Aceh, North Sumatra and West Sumatra in recent weeks has forced Indonesia to confront an uncomfortable truth. What unfolded was not only a natural disaster but a collision between an exceptional climatic cycle and a landscape steadily stripped of its natural defenses.

More than 600 people have now been confirmed dead in the country, more than four hundred remain missing, and entire communities have been torn apart by the force of water, mud, and debris that surged with little warning. The scenes have become tragically familiar, houses swallowed by landslides, rivers breaking their banks, villages buried under mud that once clung to forest roots no longer there.

This year’s climate pattern created the perfect storm. Meteorological agencies warned that an active monsoon phase combined with warm ocean temperatures would push rainfall to exceptional levels across western Indonesia.

With no COP30 roadmap, hopes of saving forests hinge on voluntary initiatives

A rare tropical storm then formed in the Malacca Strait, unleashing torrential rains and wind gusts for several days. The Malacca Strait is one of the least likely places on Earth for tropical cyclones to form, making this event an exceptional anomaly. What might have once been manageable seasonal extremes became lethal when these torrents met degraded catchments and eroded hillsides.

Heavy rain alone does not create walls of mud and logs crashing into villages, it is heavy rain falling on land that is no longer able to hold or absorb it. In many affected districts, people reported water arriving faster and more violently than anyone could remember, carrying with it an astonishing volume of uprooted trees and logs that locals insist did not come from natural forest fall alone.

Conveyor belts of timber

This is where public suspicion has grown. The floods across the three provinces did not just bring water, they brought evidence. Viral videos showed rivers transformed into conveyor belts of timber, beaches covered with logs, and bridges jammed with uprooted trunks.

Environmental groups quickly pointed to long standing problems of deforestation and illegal logging that weaken watersheds and destabilize slopes. Some officials at the local level echoed these concerns, noting that the amount of cut wood carried by the floods appeared far beyond what would be expected from natural tree fall.

While the national government has cautioned against drawing conclusions too quickly, insisting that investigations into the origins of the timber are underway, the visual evidence has only deepened public frustration. Communities living downstream know what an intact forest looks and behaves like during heavy rain, and they know what a damaged one unleashes.

Legal concessions worsen problem

Recent data reinforces the scale of the problem. Independent monitoring groups reported that Indonesia lost more than two hundred sixty thousand hectares of forest in 2024, with over ninety thousand hectares lost on the island of Sumatra alone. This level of annual loss places Indonesia among the world’s highest tropical deforestation hotspots. Although much of this deforestation occurred inside legal concessions, the ecological impact is no less severe.

When natural forest is cleared, whether for plantations, industry, or illicit timber extraction, the soil becomes exposed, drainage shifts, and slopes lose integrity. Even more troubling, authorities uncovered a major illegal logging operation in the Mentawai Islands in late 2025, seizing more than four thousand cubic meters of illicit timber. This suggests that illegal extraction remains alive in areas where oversight is weak and access is difficult.

Comment: Europe must defend its deforestation law – for forests, business and its reputation

Such practices hollow out forest structure in ways that are not always visible until disaster strikes. Government policy has played an ambiguous role in this trajectory. On one hand, Indonesia has made international commitments to curb deforestation and has deployed satellite based early warning systems to identify suspicious land clearing.

On the other hand, the expansion of legal concessions for agriculture, timber, and mining has allowed vast tracts of natural forest to be converted. Even when legal, these transitions often degrade watersheds and reduce the natural capacity of landscapes to regulate water.

Local governments, strapped for revenue and political support, frequently view concessions as economic lifelines, while enforcement against illegal operators remains uneven. The result is a patchwork of legal and illegal pressures that steadily erode ecological resilience.

Protecting forests is a safety issue

The tragedy in Sumatra marks a warning that can no longer be ignored. Climate variability is intensifying, rainfall extremes are becoming more frequent, and the combination of strong storms and weakened landscapes will make disasters deadlier if current trends continue.

Indonesia cannot control the monsoon, but it can control the health of its forests. Protecting the remaining natural forest in Sumatra is no longer simply an environmental issue, it has become a matter of public safety and national stability.

Norway pledges $3bn in boost for Brazil-led tropical forest fund

Looking forward, the government must take a sharper turn. Enforcement against illegal logging must be strengthened through transparent monitoring and community based surveillance in remote areas. The issuance of new concessions in sensitive watersheds should be paused while existing ones undergo ecological audits.

Local governments in Sumatra need sustained funding for reforestation and slope stabilization projects, not one off emergency responses. Finally, national and provincial authorities must collaborate to restore degraded catchments before the next extreme rainfall arrives.

Sumatra has paid an unbearable price for years of ecological neglect combined with a climate growing more volatile. The next disaster is a question of when, not if. Whether it becomes another national tragedy or a turning point will depend on how seriously Indonesia treats the forests that remain standing and the people living beneath them.

The post How Sumatra’s lost trees turned extreme rain into catastrophe appeared first on Climate Home News.

How Sumatra’s lost trees turned extreme rain into catastrophe

Climate Change

Greenpeace activists arrested by police helicopter after seven-hour protest on coal ship

NEWCASTLE, Sunday 30 November 2025 — Two Greenpeace Australia Pacific activists have been arrested by specialist police on a coal ship outside the Port of Newcastle, following a more than seven-hour-long peaceful protest during Rising Tide’s People’s Blockade today.

Photos and footage here

Three activists safely climbed and suspended from coal ship Yangze 16 at around 8:00am AEDT on Sunday, halting its operations and preventing its 12:15pm arrival into the Port of Newcastle. One of the activists, who was secured to the anchor chain, disembarked safely due to changing weather conditions. The other two activists, who were expertly secured to the side of the ship and holding a banner that read: PHASE OUT COAL AND GAS, were arrested at around 3:30pm by police climbers, who landed by helicopter on the ship around 1:45pm.

At the time of writing, no charges have been laid.

It comes as two other coal ships in two days were stopped by a peaceful flotilla at the People’s Blockade of the Port of Newcastle, the world’s biggest coal port. The port has been closed for the rest of Sunday as a result.

From the shore at the People’s Blockade, Joe Rafalowicz, Head of Climate and Energy at Greenpeace Australia Pacific, said:

“The right to peaceful protest is a fundamental pillar of a healthy democracy and a basic right of all Australians. Change requires showing up and speaking out, and that’s what our activists are doing in Newcastle today.

“As the world’s third-largest fossil fuel exporter, Australia plays an outsized role in the climate crisis. Peaceful protest to call on the Albanese government to set a timeline to phase out coal and gas, and stop approving new fossil fuel projects, is legitimate and valuable. Greenpeace Australia Pacific stands by and supports our activists, and stands with all peaceful climate defenders who are advocating for real climate action at the Blockade, and all around Australia.”

—ENDS—

For more information or to arrange an interview, please contact:

Kimberley Bernard: +61 407 581 404 or kbernard@greenpeace.org

Lucy Keller: +61 491 135 308 or lkeller@greenpeace.org

Greenpeace activists arrested by police helicopter after seven-hour protest on coal ship

Climate Change

From Brazil, with love

About halfway through the most recent United Nations’ annual climate change conference, COP30 in Belém, Carolina Pasquali, my counterpart at Greenpeace Brazil, started to lose her voice. She was suffering from the kind of hoarseness that kicks in when you have been speaking so much that your vocal cords become inflamed.

Carolina’s voice may have become tired during COP30, but she never fell silent. On the last morning of COP30, at Greenpeace’s final press briefing, I found myself standing behind Carolina as a press pack swarmed her, seeking answers to what was happening.

‘Who is that woman?’ I overheard one of the 56,118 registered delegates ask another.

‘With a crowd like that, she must be the Brazilian environment minister’, was the reasoned but inaccurate answer.

With Brazil hosting COP30, and particularly given the storied history of Greenpeace Brazil as a defender of the Amazon rainforest, Carolina carried an enormous load of leadership and advocacy in the lead-up and during the event. It is no wonder her voice was feeling the strain.

I’ve had the privilege of working with Carolina as part of the Greenpeace global leadership community for a few years now, and she’s an excellent colleague—thoughtful, principled, strategic, a brilliant public speaker, and in possession of a wonderful, wry sense of humour. She’s a friend and a terrific leader whom I admire deeply.

It had been Greenpeace Brazil’s vision that emergency action to halt deforestation was core to the demands that civil society brought to the COP. Given the event’s location in the Amazon, it seemed axiomatic that the goal of phasing out fossil fuels must be accompanied by the other critical half of the climate challenge: addressing deforestation, the second-largest driver of climate change.

Late in the afternoon on the second-last day of the COP, a fire broke out in the middle of the venue, sending a huge fork of flame towards the sky. It was a terrifying moment for those present in the venue. Thankfully, due to good design, the wise use of non-flammable materials, and the rapid response of first responders, there were no fatalities or serious injuries.

In her next speech, Carolina thanked those who had fought the blaze and overseen the evacuation, for their speed and bravery. And she reflected with due gravitas, this is what humanity can do: act together in the face of an emergency—whether that be a fire in a building or our whole planet facing global heating.

As it happened, COP30 got within striking distance of delivering a response that was fit for purpose in our times of planetary emergency, with support from a critical mass of countries for formal roadmaps to end deforestation as well as transition away from fossil fuels. But the official text ultimately fell short in the final hours of negotiations. As Carolina said: ‘while many governments are willing to act, a powerful minority is not.’

In these moments of failure by politicians and negotiators, it would be easy to give in to legitimate feelings of anger and frustration; but the task before us is to appraise every moment for opportunities for momentum. And the critical mass of nations that are committed to roadmaps for ending deforestation and phasing out fossil fuels offered light amidst the gloom.

And so we follow the path. We take the chances. We think through the next phase of strategy. And onwards. As Carolina said simply, ‘the work now continues.’

I’m not only grateful for Carolina’s friendship and for Greenpeace Brazil’s steadfast dedication to tackling deforestation in the Amazon, but for the entire Greenpeace network’s shared commitment.

Greenpeace is relied on for some heavy lifting at climate COPs, and our team consisted of policy experts, campaigners and other specialists from various geographies who brought their deep policy, communications, and campaigning expertise from around the world to the event,. Our morning briefings, sharing analysis, agreeing on focus and assigning tasks for the day, were possessed of that special energy that comes from a group of many backgrounds working very long hours together in common cause.

I’ve reflected over my time with Greenpeace, that when I visit any of our offices, bases or vessels, anywhere in the world, I feel at home. I am confident that you would have the same sensation of coming home too, because if you are reading this, then you are part of Greenpeace too–you, and me, Carolina, and the tens of millions of people all over the world that share our common vision of an earth restored to flourishing.

So on we go. The work continues, in love and hope, together.

Q & A

In the aftermath of the collapse of Australia’s COP31 bid, many people have reached out to ask: What happened? Why didn’t Australia get COP31? And what now?

In the lead-up to November’s COP, nobody in Australia would have anticipated that we would not be welcoming the global climate community to Adelaide next summer. Up until the very final moment when Climate and Energy Minister Chris Bowen told reporters that Türkiye would host COP31 with Australia assuming the role of president of negotiations, hope was alive that we would clinch the deal.

I suspect that the full picture of why the COP31 bid slipped through our hands is a complex mix of factors, some of which may never come to light in the public domain. What we do know is that in the UNFCCC system, decisions on COP hosts are made by full consensus rather than voting. So, for as long as Turkiye declined to withdraw its bid, it was never a done deal.

Much will no doubt be said about whether Australia could have done more to boost our chances of securing the bid. But as I said in the immediate aftermath of the announcement, whatever the forum, whoever the President, the urgency and focus of our actions cannot change. Phasing out fossil fuels and ending deforestation must be at the core of the COP31 agenda.

The task for Chris Bowen will now be to use his role as president of negotiations to drive global emissions reductions at speed and scale consistent with the Paris Agreement.

-

Climate Change4 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases4 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Renewable Energy5 months ago

US Grid Strain, Possible Allete Sale