Ahead of every Cop climate talks, think tanks, campaign groups and United Nations agencies get their number-crunchers to produce a load of reports summarising where the fight against climate change is at.

These reports can start to induce deja-vu. We’re doing some stuff to tackle climate change, usually more than the year before. But not fast enough to avoid some pretty terrifying destruction.

“Broken record,” is the title of the UN’s latest emissions gap report. “Temperatures hit new highs yet world fails to cut emissions (again),” the subtitle.

The world is breaking records for emissions and temperatures, fuelling climate disasters across the globe.

Discover how to put the world back on course for its climate goals in UNEP’s latest #EmissionsGap report: https://t.co/xTlAHFOGp1 pic.twitter.com/rYHhx9BzuA

— UN Environment Programme (@UNEP) November 21, 2023

So far, so gloomy. But the record may be about to come unstuck as some analysts predict emissions will peak in 2023.

By Cop29, we could be reading reports saying that this time the world has finally succeeded in cutting emissions – and not because a pandemic brought the global economy to a halt.

From then onwards, we will be damaging our planet less and less each year until we reach net zero and stop damaging it at all.

What is still to play for is how fast we reach that point and how much damage will have been done.

We’re nearing peak emissions…

A report by Climate Analytics finds a 70% chance that emissions will peak in 2023 and start falling in 2024, mainly thanks to electric vehicles, solar and wind power.

The International Energy Agency says similar, suggesting that fossil fuel CO2 emissions – a huge chunk of the total – could peak before 2025 and as early as 2023.

The US government’s Energy Information Administration is more pessimistic, predicting that solar won’t boom that fast and energy-related CO2 emissions will either continue to increase or plateau.

While emissions from producing electricity are going to come down, these gains will be partly cancelled out by still-increasing emissions from transport.

…but greenhouse gas levels keep rising…

But that doesn’t mean there will be less greenhouse gas in the atmosphere each year. Even if you pour less and less water into a bath, the bath still gets fuller each time.

The World Meteorological Organization reports that carbon dioxide concentrations in the air were 50% higher than pre-industrial levels for the first time in 2022. Methane and nitrous oxide levels also rose.

Greenhouse gas levels in our atmosphere continue to rise.

Concentrations of CO2, which is responsible for most of the warming effect on our climate, were a full 50% above the pre-industrial era for the first time in 2022. #COP28 #StateofClimatehttps://t.co/tm0uuH4Gx0 pic.twitter.com/Gs2yhRQKUt— World Meteorological Organization (@WMO) November 15, 2023

…as does the earth’s temperature…

The world is now on average 1.25C hotter than it was in the latter half of the nineteenth century.

Last year, the United Nations Environment Programme (Unep) said governments’ climate plans would put us on course for 2.4-2.8C of warming.

Since then, very few countries have increased their ambition and emissions kept rising, so they now say we’re on course for 2.5-3C of warming.

That’s if governments plans are fully implemented. But the report says that most countries aren’t doing enough to meet their promises.

…and the damage done…

Rising emissions mean rising temperatures which means rising destruction caused by climate change. This devastation is hard to measure but there are a few metrics we can use.

A study in the Lancet medical journal found that climate change made 127 million extra people go hungry in 2021, compared to the 80s, 90s and noughties.

They found it increased the potential of mosquitos to transmit dengue fever transmission by about a quarter and put 1.4 billion people at risk of vibriosis as warmer water helps bacteria in the sea thrive.

The insurance company Swiss Re says people are losing more and more of their property because of storms, floods and wildfires.

With all these impacts rising, it’s more important than ever to adapt to climate change. But Unep’s adaptation gap report finds developing countries got less adaptation finance in 2021 than they did in 2020. They need an estimated $194-366 billion. They got $21 billion.

Unlock the path forward!

UNEP’s 2023 #AdaptationGap Report identifies 7 ways to increase financing and prevent future loss and damage from the devastating impacts of the #ClimateCrisis.

Explore here: https://t.co/pxZas4WpKE

— UN Environment Programme (@UNEP) November 9, 2023

…and investment in fossil fuel production

The world is still investing over $1 trillion a year in fossil fuels – almost double the level the IEA judges compatible with 1.5C of global warming.

Countries like the US, Brazil, Saudi Arabia, Russia and Qatar are boosting oil and gas production, while India slows down the global decline in coal mining.

Demand for fossil fuels is about to peak

While the supply of fossil fuels is increasing, the IEA says the demand for coal, oil and gas has either peaked or is about to peak.

Coal is about to start a rapid decline, the IEA predicts, while demand for oil and gas stays at about the level it is now for a few decades.

That's not good enough to limit global warming to 1.5C but it does suggest continued investment in fossil fuel supply is economically as well as environmentally foolish.

One sub-set of the fossil fuel market where supply is forecast to outstrip demand is liquified natural gas. This is when gas is turned into a liquid, put on a ship and sailed to customers around the world.

The US and Qatar have led a rush into this market to replace the piped Russian gas that places like Europe used to rely on. When this new LNG export infrastructure is up and running in a few years time, the IEA predicts a glut.

Solar is booming...

Solar continues to be climate change's success story. For a few years now, the world has invested more in clean energy than fossil fuels and that gap is growing.

Chinese factories are pumping out solar panels so fast we don't know what to do with them. If they can be connected to the grids and replace fossil fuels as fast as they are being built, limiting warming to 1.5C becomes a lot easier.

...and so are electric vehicles...

Five years ago, less than 2% of new cars were electric. Now that figure is more like 10%.

In a few years time, the World Resources Institute predicts, that figure will pass 50% and get up to near 100% by the end of the decade.

It will take longer for all cars on the road to be electric and buses and motorbikes are lagging behind still.

But electric vehicles are taking a big chunk out of oil demand and of road transport's 10% of global emissions.

...and heat pumps

When Russia invaded Ukraine, Europeans and their governments scrambled to stop heating their homes with Russian gas.

That led to a boom in heat pumps, which run on electricity and are around three times more efficient than gas boilers. Sales soared 40% in Europe and 10% across the world.

The post In numbers: The state of the climate ahead of Cop28 appeared first on Climate Home News.

Climate Change

DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Absolute State of the Union

‘DRILL, BABY’: US president Donald Trump “doubled down on his ‘drill, baby, drill’ agenda” in his State of the Union (SOTU) address, said the Los Angeles Times. He “tout[ed] his support of the fossil-fuel industry and renew[ed] his focus on electricity affordability”, reported the Financial Times. Trump also attacked the “green new scam”, noted Carbon Brief’s SOTU tracker.

COAL REPRIEVE: Earlier in the week, the Trump administration had watered down limits on mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants, reported the Financial Times. It remains “unclear” if this will be enough to prevent the decline of coal power, said Bloomberg, in the face of lower-cost gas and renewables. Reuters noted that US coal plants are “ageing”.

OIL STAY: The US Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments brought by the oil industry in a “major lawsuit”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper said the firms are attempting to head off dozens of other lawsuits at state level, relating to their role in global warming.

SHIP-SHILLING: The Trump administration is working to “kill” a global carbon levy on shipping “permanently”, reported Politico, after succeeding in delaying the measure late last year. The Guardian said US “bullying” could be “paying off”, after Panama signalled it was reversing its support for the levy in a proposal submitted to the UN shipping body.

Around the world

- RARE EARTHS: The governments of Brazil and India signed a deal on rare earths, said the Times of India, as well as agreeing to collaborate on renewable energy.

- HEAT ROLLBACK: German homes will be allowed to continue installing gas and oil heating, under watered-down government plans covered by Clean Energy Wire.

- BRAZIL FLOODS: At least 53 people died in floods in the state of Minas Gerais, after some areas saw 170mm of rain in a few hours, reported CNN Brasil.

- ITALY’S ATTACK: Italy is calling for the EU to “suspend” its emissions trading system (ETS) ahead of a review later this year, said Politico.

- COOKSTOVE CREDITS: The first-ever carbon credits under the Paris Agreement have been issued to a cookstove project in Myanmar, said Climate Home News.

- SAUDI SOLAR: Turkey has signed a “major” solar deal that will see Saudi firm ACWA building 2 gigawatts in the country, according to Agence France-Presse.

$467 billion

The profits made by five major oil firms since prices spiked following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine four years ago, according to a report by Global Witness covered by BusinessGreen.

Latest climate research

- Claims about the “fingerprint” of human-caused climate change, made in a recent US Department of Energy report, are “factually incorrect” | AGU Advances

- Large lakes in the Congo Basin are releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere from “immense ancient stores” | Nature Geoscience

- Shared Socioeconomic Pathways – scenarios used regularly in climate modelling – underrepresent “narratives explicitly centring on democratic principles such as participation, accountability and justice” | npj Climate Action

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

The constituency of Richard Tice MP, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of Reform UK, is the second-largest recipient of flood defence spending in England, according to new Carbon Brief analysis. Overall, the funding is disproportionately targeted at coastal and urban areas, many of which have Conservative or Liberal Democrat MPs.

Spotlight

Is there really a UK ‘greenlash’?

This week, after a historic Green Party byelection win, Carbon Brief looks at whether there really is a “greenlash” against climate policy in the UK.

Over the past year, the UK’s political consensus on climate change has been shattered.

Yet despite a sharp turn against climate action among right-wing politicians and right-leaning media outlets, UK public support for climate action remains strong.

Prof Federica Genovese, who studies climate politics at the University of Oxford, told Carbon Brief:

“The current ‘war’ on green policy is mostly driven by media and political elites, not by the public.”

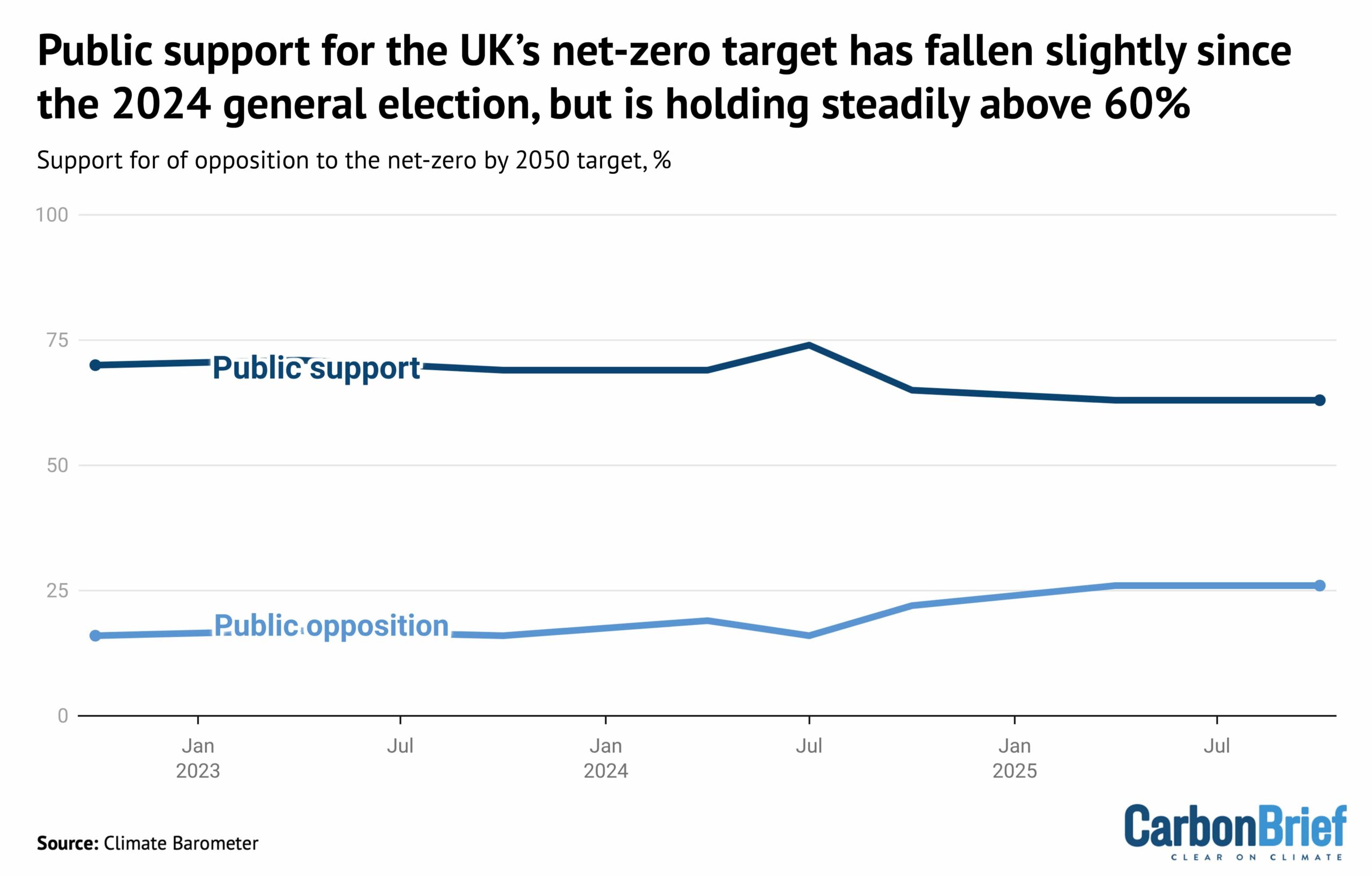

Indeed, there is still a greater than two-to-one majority among the UK public in favour of the country’s legally binding target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, as shown below.

Steve Akehurst, director of public-opinion research initiative Persuasion UK, also noted the growing divide between the public and “elites”. He told Carbon Brief:

“The biggest movement is, without doubt, in media and elite opinion. There is a bit more polarisation and opposition [to climate action] among voters, but it’s typically no more than 20-25% and mostly confined within core Reform voters.”

Conservative gear shift

For decades, the UK had enjoyed strong, cross-party political support for climate action.

Lord Deben, the Conservative peer and former chair of the Climate Change Committee, told Carbon Brief that the UK’s landmark 2008 Climate Change Act had been born of this cross-party consensus, saying “all parties supported it”.

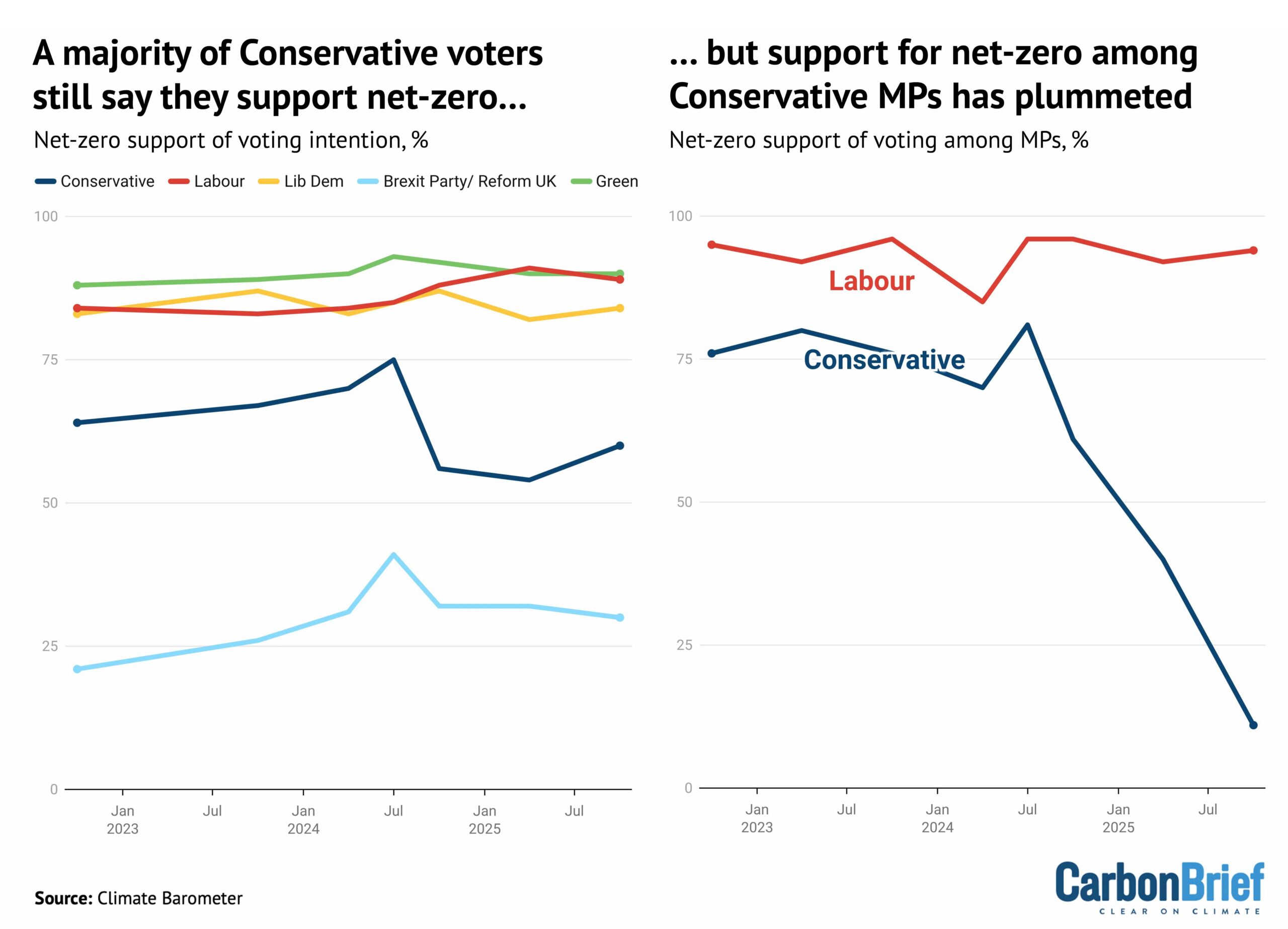

Since their landslide loss at the 2024 election, however, the Conservatives have turned against the UK’s target of net-zero emissions by 2050, which they legislated for in 2019.

Curiously, while opposition to net-zero has surged among Conservative MPs, there is majority support for the target among those that plan to vote for the party, as shown below.

Dr Adam Corner, advisor to the Climate Barometer initiative that tracks public opinion on climate change, told Carbon Brief that those who currently plan to vote Reform are the only segment who “tend to be more opposed to net-zero goals”. He said:

“Despite the rise in hostile media coverage and the collapse of the political consensus, we find that public support for the net-zero by 2050 target is plateauing – not plummeting.”

Reform, which rejects the scientific evidence on global warming and campaigns against net-zero, has been leading the polls for a year. (However, it was comfortably beaten by the Greens in yesterday’s Gorton and Denton byelection.)

Corner acknowledged that “some of the anti-net zero noise…[is] showing up in our data”, adding:

“We see rising concerns about the near-term costs of policies and an uptick in people [falsely] attributing high energy bills to climate initiatives.”

But Akehurst said that, rather than a big fall in public support, there had been a drop in the “salience” of climate action:

“So many other issues [are] competing for their attention.”

UK newspapers published more editorials opposing climate action than supporting it for the first time on record in 2025, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Global ‘greenlash’?

All of this sits against a challenging global backdrop, in which US president Donald Trump has been repeating climate-sceptic talking points and rolling back related policy.

At the same time, prominent figures have been calling for a change in climate strategy, sold variously as a “reset”, a “pivot”, as “realism”, or as “pragmatism”.

Genovese said that “far-right leaders have succeeded in the past 10 years in capturing net-zero as a poster child of things they are ‘fighting against’”.

She added that “much of this is fodder for conservative media and this whole ecosystem is essentially driving what we call the ‘greenlash’”.

Corner said the “disconnect” between elite views and the wider public “can create problems” – for example, “MPs consistently underestimate support for renewables”. He added:

“There is clearly a risk that the public starts to disengage too, if not enough positive voices are countering the negative ones.”

Watch, read, listen

TRUMP’S ‘PETROSTATE’: The US is becoming a “petrostate” that will be “sicker and poorer”, wrote Financial Times associate editor Rana Forohaar.

RHETORIC VS REALITY: Despite a “political mood [that] has darkened”, there is “more green stuff being installed than ever”, said New York Times columnist David Wallace-Wells.

CHINA’S ‘REVOLUTION’: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast reported from China on the “green energy revolution” taking place in the country.

Coming up

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean, Brasília

- 3 March: UK spring statement

- 4-11 March: China’s “two sessions”

- 5 March: Nepal elections

Pick of the jobs

- The Guardian, senior reporter, climate justice | Salary: $123,000-$135,000. Location: New York or Washington DC

- China-Global South Project, non-resident fellow, climate change | Salary: Up to $1,000 a month. Location: Remote

- University of East Anglia, PhD in mobilising community-based climate action through co-designed sports and wellbeing interventions | Salary: Stipend (unknown amount). Location: Norwich, UK

- TABLE and the University of São Paulo, Brazil, postdoctoral researcher in food system narratives | Salary: Unknown. Location: Pirassununga, Brazil

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

Seven Pacific island nations say they will demand heftier levies on global shipping emissions if opponents of a green deal for the industry succeed in reopening negotiations on the stalled accord.

The United States and Saudi Arabia persuaded countries not to grant final approval to the International Maritime Organization’s Net-Zero Framework (NZF) in October and they are now leading a drive for changes to the deal.

In a joint submission seen by Climate Home News, the seven climate-vulnerable Pacific countries said the framework was already a “fragile compromise”, and vowed to push for a universal levy on all ship emissions, as well as higher fees . The deal currently stipulates that fees will be charged when a vessel’s emissions exceed a certain level.

“For many countries, the NZF represents the absolute limit of what they can accept,” said the unpublished submission by Fiji, Kiribati, Vanuatu, Nauru, Palau, Tuvalu and the Solomon Islands.

The countries said a universal levy and higher charges on shipping would raise more funds to enable a “just and equitable transition leaving no country behind”. They added, however, that “despite its many shortcomings”, the framework should be adopted later this year.

US allies want exemption for ‘transition fuels’

The previous attempt to adopt the framework failed after governments narrowly voted to postpone it by a year. Ahead of the vote, the US threatened governments and their officials with sanctions, tariffs and visa restrictions – and President Donald Trump called the framework a “Green New Scam Tax on Shipping”.

Since then, Liberia – an African nation with a major low-tax shipping registry headquartered in the US state of Virginia – has proposed a new measure under which, rather than staying fixed under the NZF, ships’ emissions intensity targets change depending on “demonstrated uptake” of both “low-carbon and zero-carbon fuels”.

The proposal places stringent conditions on what fuels are taken into consideration when setting these targets, stressing that the low- and zero-carbon fuels should be “scalable”, not cost more than 15% more than standard marine fuels and should be available at “sufficient ports worldwide”.

This proposal would not “penalise transitional fuels” like natural gas and biofuels, they said. In the last decade, the US has built a host of large liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals, which the Trump administration is lobbying other countries to purchase from.

The draft motion, seen by Climate Home News, was co-sponsored by US ally Argentina and also by Panama, a shipping hub whose canal the US has threatened to annex. Both countries voted with the US to postpone the last vote on adopting the framework.

The IMO’s Panamanian head Arsenio Dominguez told reporters in January that changes to the framework were now possible.

“It is clear from what happened last year that we need to look into the concerns that have been expressed [and] … make sure that they are somehow addressed within the framework,” he said.

Patchwork of levies

While the European Union pushed firmly for the framework’s adoption, two of its shipping-reliant member states – Greece and Cyprus – abstained in October’s vote.

After a meeting between the Greek shipping minister and Saudi Arabia’s energy minister in January, Greece said a “common position” united Greece, Saudi Arabia and the US on the framework.

If the NZF or a similar instrument is not adopted, the IMO has warned that there will be a patchwork of differing regional levies on pollution – like the EU’s emissions trading system for ships visiting its ports – which will be complicated and expensive to comply with.

This would mean that only countries with their own levies and with lots of ships visiting their ports would raise funds, making it harder for other nations to fund green investments in their ports, seafarers and shipping companies. In contrast, under the NZF, revenues would be disbursed by the IMO to all nations based on set criteria.

Anais Rios, shipping policy officer from green campaign group Seas At Risk, told Climate Home News the proposal by the Pacific nations for a levy on all shipping emissions – not just those above a certain threshold – was “the most credible way to meet the IMO’s climate goals”.

“With geopolitics reframing climate policy, asking the IMO to reopen the discussion on the universal levy is the only way to decarbonise shipping whilst bringing revenue to manage impacts fairly,” Rios said.

“It is […] far stronger than the Net-Zero Framework that is currently on offer.”

The post Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen appeared first on Climate Home News.

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

Climate Change

Doubts over European SAF rules threaten cleaner aviation hopes, investors warn

Doubts over whether governments will maintain ambitious targets on boosting the use of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) are a threat to the industry’s growth and play into the hands of fossil fuel companies, investors warned this week.

Several executives from airlines and oil firms have forecast recently that SAF requirements in the European Union, United Kingdom and elsewhere will be eased or scrapped altogether, potentially upending the aviation industry’s main policy to shrink air travel’s growing carbon footprint.

Such speculation poses a “fundamental threat” to the SAF industry, which mainly produces an alternative to traditional kerosene jet fuel using organic feedstocks such as used cooking oil (UCO), Thomas Engelmann, head of energy transition at German investment manager KGAL, told the Sustainable Aviation Fuel Investor conference in London.

He said fossil fuel firms would be the only winners from questions about compulsory SAF blending requirements.

The EU and the UK introduced the world’s first SAF mandates in January 2025, requiring fuel suppliers to blend at least 2% SAF with fossil fuel kerosene. The blending requirement will gradually increase to reach 32% in the EU and 22% in the UK by 2040.

Another case of diluted green rules?

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January, CEO of French oil and gas company TotalEnergies Patrick Pouyanné said he would bet “that what happened to the car regulation will happen to the SAF regulation in Europe”.

The EU watered down green rules for car-makers in March 2025 after lobbying from car companies, Germany and Italy.

“You will see. Today all the airline companies are fighting [against the EU’s 2030 SAF target of 6%],” Pouyanne said, even though it’s “easy to reach to be honest”.

While most European airline lobbies publicly support the mandates, Ryanair Group CEO Michael O’Leary said last year that the SAF is “nonsense” and is “gradually dying a death, which is what it deserves to do”.

EU and UK stand by SAF targets

But the EU and the British government have disputed that. EU transport commissioner Apostolos Tzitzikostas said in November that the EU’s targets are “stable”, warning that “investment decisions and construction must start by 2027, or we will miss the 2030 targets”.

UK aviation minister Keir Mather told this week’s investor event that meeting the country’s SAF blending requirement of 10% by 2030 was “ambitious but, with the right investment, the right innovation and the right outlook, it is absolutely within our reach”.

“We need to go further and we need to go faster,” Mather said.

SAF investors and developers said such certainty on SAF mandates from policymakers was key to drawing the necessary investment to ramp up production of the greener fuel, which needs to scale up in order to bring down high production costs. Currently, SAF is between two and seven times more expensive than traditional jet fuel.

Urbano Perez, global clean molecules lead at Spanish bank Santander, said banks will not invest if there is a perceived regulatory risk.

David Scott, chair of Australian SAF producer Jet Zero Australia, said developing SAF was already challenging due to the risks of “pretty new” technology requiring high capital expenditure.

“That’s a scary model with a volatile political environment, so mandate questioning creates this problem on steroids”, Scott said.

Others played down the risk. Glenn Morgan, partner at investment and advisory firm SkiesFifty, said “policy is always a risk”, adding that traditional oil-based jet fuel could also lose subsidies.

Asian countries join SAF mandate adopters

In Asia, Singapore, South Korea, Thailand and Japan have recently adopted SAF mandates, and Matti Lievonen, CEO of Asia-based SAF producer EcoCeres, predicted that China, Indonesia and Hong Kong would follow suit.

David Fisken, investment director at the Australian Trade and Investment Commission, said the Australian government, which does not have a mandate, was watching to see how the EU and UK’s requirements played out.

The US does not have a SAF mandate and under President Donald Trump the government has slashed tax credits available for SAF producers from $1.75 a gallon to $1.

Is the world’s big idea for greener air travel a flight of fancy?

SAF and energy security

SAF’s potential role in boosting energy security was a major theme of this week’s discussions as geopolitical tensions push the issue to the fore.

Marcella Franchi, chief commercial officer for SAF at France’s Haffner Energy, said the Canadian government, which has “very unsettling neighbours at the moment”, was looking to produce SAF to protect its energy security, especially as it has ample supplies of biomass to use as potential feedstock.

Similarly, German weapons manufacturer Rheinmetall said last year it was working on plans that would enable European armed forces to produce their own synthetic, carbon-neutral fuel “locally and independently of global fossil fuel supply chain”.

Scott said Australia needs SAF to improve its fuel security, as it imports almost 99% of its liquid fuels.

He added that support for Australian SAF production is bipartisan, in part because it appeals to those more concerned about energy security than tackling climate change.

The post Doubts over European SAF rules threaten cleaner aviation hopes, investors warn appeared first on Climate Home News.

Doubts over European SAF rules threaten cleaner aviation hopes, investors warn

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits