Olá da Madeira! The island – a green paradise in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean – has been home to us for almost three months already. How the time flies!

We are Lara and Karo, one of 8 teams that currently conduct experiments all over the world as part of this year’s GAME project. Lara is a Marine Biology student currently enrolled at the University of Rostock and she is collecting data for her master thesis within the project. When she heard about GAME from her professor, she knew she had to be part of it! Karo is studying Biological Oceanography in Kiel. She found her passion for marine sciences quite recently and has never lived close to the ocean on beforehand. It was a dream of them both to join this project!

This year’s aim is – like in the previous years since 2021 – to investigate the effects of artificial light at night (or ALAN for short). We want to see how this phenomenon affects macroalgae in their ability to photosynthesize, grow and defend themselves against grazers. After an intense planning phase in March, during which we decided on the design of our experiments, we were more than glad to leave cold and grey northern Germany behind and escape into the sunny, subtropical climate of Madeira.

Finding accommodation was not easy, but in the end, we found a nice flat in the capital city Funchal with (almost) an ocean view! More than this, we have a balcony where we’ve enjoyed many lengthy weekend breakfasts.

We had an enjoyable first week when we settled into our flat, scouted the city and tried to figure out the bus system, which proved to be kind of complicated, since there are so many different bus companies here. One thing we learned very quickly, though: walking on this island requires strong calves. Madeira is hills…hills…and more hills. This is why you hardly ever see local people walking here – sometimes you get funny looks when you are doing a typical German “Spaziergang” (which is more like a hike over here), and you really have to watch out not to get run over by a bus or a car.

Then, we finally met the team of the Marine and Environmental Science Centre “MARE”. In our first meeting, we sat together with our supervisors (who are all former GAME participants!) and discussed how we could make our experiments here successful. Everyone was excited and motivated to get our project started!

Not long after, we made our first trip to the laboratory where we are conducting our experiments together. It is located in Quinta do Lorde, a place on the easternmost part of the island. It is close to the peninsula “Ponta de São Lourenço” which offers stunning views over the rugged coastline of the volcanic island. This part of the island is very dry and it almost feels like you have stepped into a desert – quite the contrast to the rest of Madeira, which is a lush, green paradise.

It is also the perfect spot for investigating ALAN, since it is very isolated and therefore mostly uninfluenced by nighttime illumination. Hence, the marine life here is not already adapted to light at night. The only downgrade is: the lab is located quite far away from Funchal, where we live. Most days, we have to take a bus that takes the scenic route and drives 1.5 hours along the coast, up and down the hills. At least we are rewarded with pretty ocean views during the drive – or we go for a little nap, especially after a long day in the lab. Thankfully, we can sometimes catch a ride in the car with our supervisors.

In the first weeks, we worked hard to build up our experimental set-up. Thanks to the great work of former GAME students, our lab is already equipped with most of the materials that we need, so we could quickly set up a flow-through system to supply running water to our algae. But we celebrated too soon: The complete water system of the lab had to be cleaned with bleach due to some pesky epiphytic growth and that meant that we had to re-do the flow through system again from scratch. We patiently cut tubes, and more tubes and connected them with little plastic suppliers, which let out filtered seawater to each of our 72 experimental tanks.

To give our algae as much light as possible, so that they are able to happily photosynthesize, we decided to order more LED lamps. One thing we did not anticipate: Madeira is located in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean, around 1000 km from the European coastline (the African coast is actually closer!), so equipment can take a loooong time to arrive. We were lucky that our lamps arrived “only” 3 weeks later, but already we faced the next challenge: connecting our lights to the control unit, with which we want to regulate the light intensity that our algae will be exposed to, proved to be more difficult than we had previously thought. However, with the help of the lab technician Patrício we quickly found a solution!

When we weren’t diligently building our set-up, we spent our days snorkelling in different places on the south coast of the island, looking for algae “candidates” that we could use in our experiments. Easier said than done, because the waters around Madeira are depleted in nutrients and large macroalgae are rare to find. We quickly decided on using Halopteris scoparia, a brown macroalgae that is quite abundant in the upper subtidal and therefore possible for us to collect while snorkelling. Another (particularly interesting) candidate is Rugulopteryx okamurae, an invasive brown alga, that has first been introduced on the north coast of Madeira in 2021 and since then spread rapidly – it is even growing on the pontoons in the marina outside our lab. It could be especially interesting to investigate how this species reacts to ALAN in comparison to native algae.

Since we want to investigate how ALAN affects the defence capacity of our algae, we also had to find suitable grazers (=algae eaters). Our options were less than ideal: Should we use sea urchins (even though they are very hungry and consume our algae in too large amounts) or intertidal snails (even though this makes less sense ecologically, because our algae come from the subtidal). In the end, we decided on the sea urchin Paracentrotus lividus, which we can easily collect in the tide pools next to our lab. Did we say easy? – To get the hang of how to sample these little algae eaters took some blood, sweat and tears. Equipped with forks and buckets; after waiting for low tide to arrive, we wade into the tide pools and try to gently (or not so gently) persuade our sea urchins to come out of the holes in the rock that they like to sit in. We always take good care not to injure or stress them too much, but some unfortunately have already met their fate.

Before we could start with the main experiments, we had to test a few things. For instance, how much and when the sea urchins eat and how much the algae photosynthesize. To find this out, we carried out some pilot studies – more or less successfully. During one of our pilot studies all our sea urchins mysteriously died, probably after some contamination[LM1] [LH2] of the water. In addition to this, our method for measuring the oxygen production initially did not work, because the oxygen values we measured did not stabilize and photosynthesized waaaay too slowly despite looking perfectly healthy. After many hours of trial and error, we fortunately found a way that should allow us to accurately assess the oxygen evolution. For this[LM3] , we increased the light intensity to help the algae photosynthesize more quickly and also got a multi-position magnetic stirrer where we can put multiple of our containers with algae on simultaneously. A little magnetic bar keeps the water in the containers in constant motion, resulting in more stable oxygen measurements.

Furthermore, we have another nice tool available here. It is a PAM, which is short for Pulse Amplitude Modulation. Behind this rather complicated name lies a technology with which we can assess how well our algae are absorbing sunlight for photosynthesis and ultimately determine their health status. Because no one in the institute had used the device before, we had to do a lot of headache-inducing reading (the 200-page manual is not easy to understand) and carry out some test runs to get prepared for the measurements. Our weekly meetings with the other GAME participants became crucial for discussing challenges and brainstorming solutions together – so far this project has been a huge learning curve for the both of us.

Our lunch breaks we share with the lizards. Fun fact: there are more lizards than mice on Madeira! They are called Madeira lizards (Teira dugesii) and they are endemic to some of the Macaronesian islands. They are very curious creatures – especially when we unpack our food. They sometimes even like to jump on our feet, but you have to watch out that they don’t crawl inside your backpack, and you accidentally take home a new pet.

When we are not in the lab, we also know how to have fun (not that being in the lab is not fun). Madeira is an island full of amazing places and activities, and it’s a hiker’s paradise! There are a lot of different routes to explore, very famous are “levada” walks here. Levadas are old, narrow water channels that wind through the mountains. They were constructed to carry water from the misty mountains down to the drier parts of the island to water the crops of the farmers. You can walk along these levadas and enjoy the views over the island!

Besides doing a lot of hiking and training our calves, we have spotted some dolphins, explored different beaches, and even got swept up in the European Championships fever. Since Madeira is Cristiano Ronaldo’s birthplace, people here (young and old) are fans, and we joined the locals cheering for the Portuguese soccer team. Of course, we also had to try Madeira’s famous “poncha”, a traditional drink with rum and fresh fruit juice – typically lemon, orange, or – our favourite – maracuja. Another drink is Nikita, which is a mixture of pineapple juice, ice cream and beer. It tastes… well… interesting, as Karo’s face in the picture shows.

Madeira’s climate is perfect for growing all kinds of tropical fruits and other plants. What people keep as house plants in Germany, grows here in ditches next to the road, or in the size of trees – Monstera leaves get almost bigger than oneself! We also tried some fruits here that we have never seen before in our life. Our flatmate’s supervisor even has avocado trees in his backyard, which we sometimes get a share of – a luxury we will sorely miss back in Germany.

Another thing we learned here: you can never trust the weather forecast. In Funchal, situated on the south coast, the weather is usually pretty dry and sunny. However, it’s a different story for the North coast, where it rains more frequently, and temperatures are cooler. But even here on the sunny south coast, you never know what to wear. You could burn under the African sun or in the next second freeze from the wind, especially in the evenings, when the sun is already down. The onion-principle (a German favourite) really proves best.

We have been really enjoying our time here so far and we are sure by the end of September we will not want to go back to Germany. We have finished the first experiment and are soon starting the second one, we are excited to see what happens!

Lights, Algae, Action! Researching light pollution in the middle of the Atlantic

Ocean Acidification

What is the High Seas Treaty and Why Does It Matter?

You may have seen headlines recently about a new global treaty that went into effect just as news broke that the United States would be withdrawing from a number of other international agreements. It’s a confusing time in the world of environmental policy, and Ocean Conservancy is here to help make it clearer while, of course, continuing to protect our ocean.

What is the High Seas Treaty?

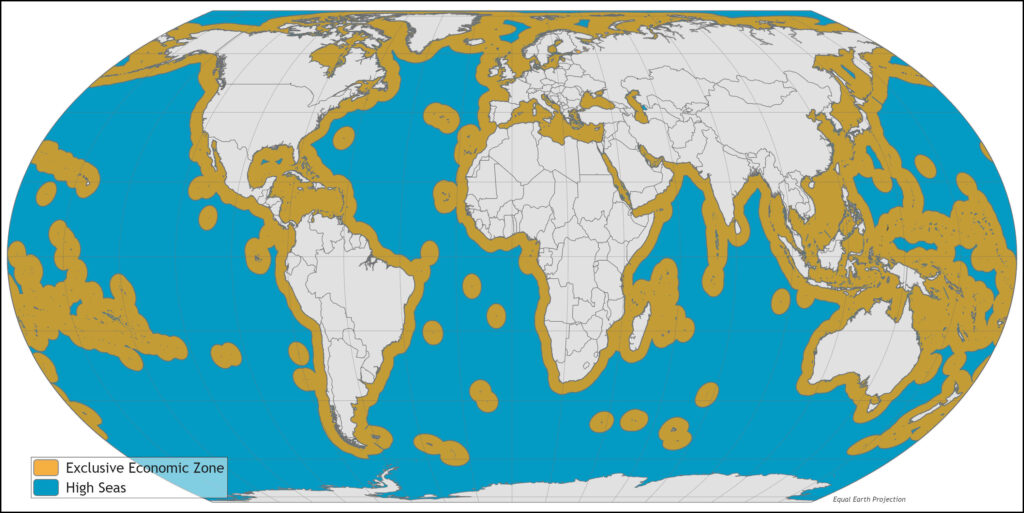

The “High Seas Treaty,” formally known as the Agreement on the Conservation and Sustainable Use of Marine Biological Diversity of Areas Beyond National Jurisdiction (BBNJ) Agreement, went into effect on January 17, 2026. We celebrated this win last fall, when the agreement reached the 60 ratifications required for its entry into force. (Since then, an additional 23 countries have joined!) It is the first comprehensive international legal framework dedicated to addressing the conservation and sustainable use of the high seas (the area of the ocean that lies 200 miles beyond the shorelines of individual countries).

To “ensure the conservation and sustainable use of marine biological diversity” of these areas, the BBNJ addresses four core pillars of ocean governance:

- Marine genetic resources: The high seas contain genetic resources (genes of plants, animals and microbes) of great value for pharmaceuticals, cosmetics and food production. The treaty will ensure benefits accrued from the development of these resources are shared equitably amongst nations.

- Area-based management tools such as the establishment of marine protected areas (MPAs) in international waters. Protecting important areas of the ocean is essential for healthy and resilient ecosystems and marine biodiversity.

- Environmental impact assessments (EIA) will allow us to better understand the potential impacts of proposed activities that may harm the ocean so that they can be managed appropriately.

- Capacity-building and the transfer of marine technology with particular emphasis on supporting developing states. This section of the treaty is designed to ensure all nations benefit from the conservation and sustainable use of marine biodiversity through, for example, the sharing of scientific information.

Get Ocean Updates in Your Inbox

Sign up with your email and never miss an update.

Why is the High Seas Treaty Important?

The BBNJ agreement is legally binding for the countries that have ratified it and is the culmination of nearly two decades of negotiations. Its enactment is a historic milestone for global ocean governance and a significant advancement in the collective protection of marine ecosystems.

The high seas represent about two-thirds of the global ocean, and yet less than 10% of this area is currently protected. This has meant that the high seas have been vulnerable to unregulated or illegal fishing activities and unregulated waste disposal. Recognizing a major governance gap for nearly half of the planet, the agreement puts in place a legal framework to conserve biodiversity.

As it promotes strengthened international cooperation and accountability, the agreement will establish safeguards aimed at preventing and reversing ocean degradation and promoting ecosystem restoration. Furthermore, it will mobilize the international community to develop new legal, scientific, financial and compliance mechanisms, while reinforcing coordination among existing treaties, institutions and organizations to address long-standing governance gaps.

How is Ocean Conservancy Supporting the BBNJ Agreement?

Addressing the global biodiversity crisis is a key focal area for Ocean Conservancy, and the BBNJ agreement adds important new tools to the marine conservation toolbox and a global commitment to better protect the ocean.

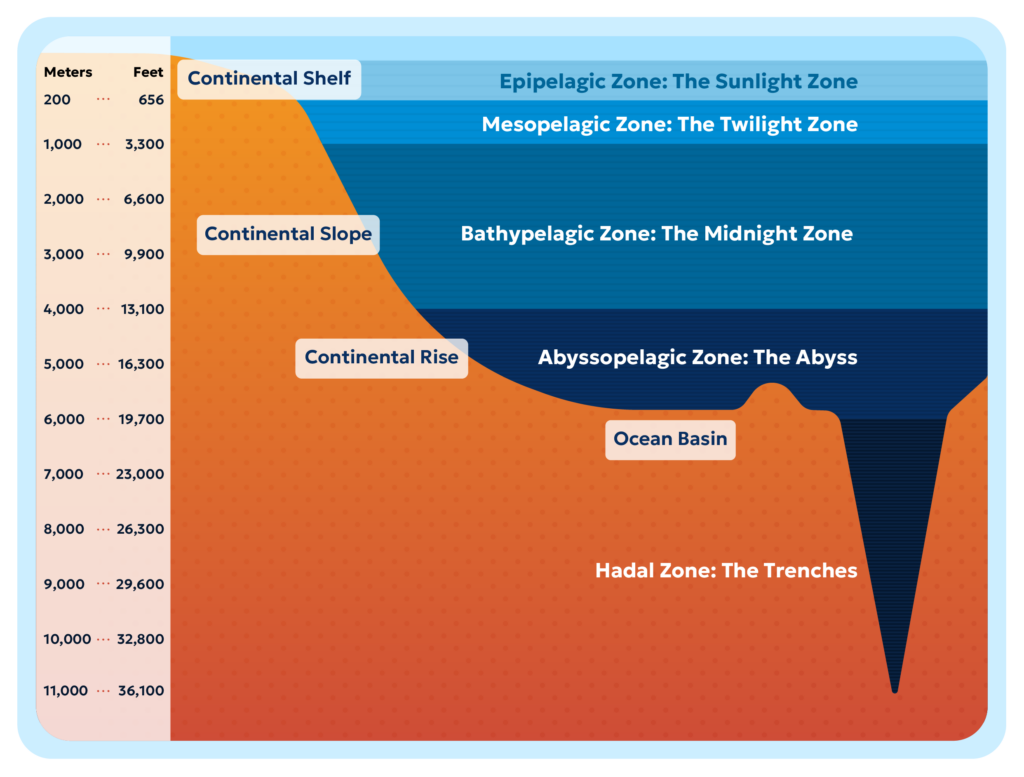

Ocean Conservancy’s efforts to protect the “ocean twilight zone”—an area of the ocean 200-1000m (600-3000 ft) below the surface—is a good example of why the BBNJ agreement is so important. The ocean twilight zone (also known as the mesopelagic zone) harbors incredible marine biodiversity, regulates the climate and supports the health of ocean ecosystems. By some estimates, more than 90% of the fish biomass in the ocean resides in the ocean twilight zone, attracting the interest of those eager to develop new sources of protein for use in aquaculture feed and pet foods.

Done poorly, such development could have major ramifications for the health of our planet, jeopardizing the critical role these species play in regulating the planet’s climate and sustaining commercially and ecologically significant marine species. Species such as tunas (the world’s most valuable fishery), swordfish, salmon, sharks and whales depend upon mesopelagic species as a source of food. Mesopelagic organisms would also be vulnerable to other proposed activities including deep-sea mining.

A significant portion of the ocean twilight zone is in the high seas, and science and policy experts have identified key gaps in ocean governance that make this area particularly vulnerable to future exploitation. The BBNJ agreement’s provisions to assess the impacts of new activities on the high seas before exploitation begins (via EIAs) as well as the ability to proactively protect this area can help ensure the important services the ocean twilight zone provides to our planet continue well into the future.

What’s Next?

Notably, the United States has not ratified the treaty, and, in fact, just a few days before it went into effect, the United States announced its withdrawal from several important international forums, including many focused on the environment. While we at Ocean Conservancy were disappointed by this announcement, there is no doubt that the work will continue.

With the agreement now in force, the first Conference of the Parties (COP1), also referred to as the BBNJ COP, will convene within the next year and will play a critical role in finalizing implementation, compliance and operational details under the agreement. Ocean Conservancy will work with partners to ensure implementation of the agreement is up to the challenge of the global biodiversity crisis.

The post What is the High Seas Treaty and Why Does It Matter? appeared first on Ocean Conservancy.

https://oceanconservancy.org/blog/2026/02/25/high-seas-treaty/

Ocean Acidification

Hälsningar från Åland och Husö biological station

On Åland, the seasons change quickly and vividly. In summer, the nights never really grow dark as the sun hovers just below the horizon. Only a few months later, autumn creeps in and softly cloaks the island in darkness again. The rhythm of the seasons is mirrored by the biological station itself; researchers, professors, and students arrive and depart, bringing with them microscopes, incubators, mesocosms, and field gear to study the local flora and fauna peaking in the mid of summer.

This year’s GAME project is the final chapter of a series of studies on light pollution. Together, we, Pauline & Linus, are studying the effects of artificial light at night (ALAN) on epiphytic filamentous algae. Like the GAME site in Japan, Akkeshi, the biological station Husö here on Åland experiences very little light pollution, making it an ideal place to investigate this subject.

We started our journey at the end of April 2025, just as the islands were waking up from winter. The trees were still bare, the mornings frosty, and the streets quiet. Pauline, a Marine Biology Master’s student from the University of Algarve in Portugal, arrived first and was welcomed by Tony Cederberg, the station manager. Spending the first night alone on the station was unique before the bustle of the project began.

Linus, a Marine Biology Master’s student at Åbo Akademi University in Finland, joined the next day. Husö is the university’s field station and therefore Linus has been here for courses already. However, he was excited to spend a longer stretch at the station and to make the place feel like a second home.

Our first days were spent digging through cupboards and sheds, reusing old materials and tools from previous years, and preparing the frames used by GAME 2023. We chose Hamnsundet as our experimental site, (i.e. the same site that was used for GAME 2023), which is located at the northeast of Åland on the outer archipelago roughly 40 km from Husö. We got permission to deploy the experiments by the local coast guard station, which was perfect. The location is sheltered from strong winds, has electricity access, can be reached by car, and provides the salinity conditions needed for our macroalga, Fucus vesiculosus, to survive.

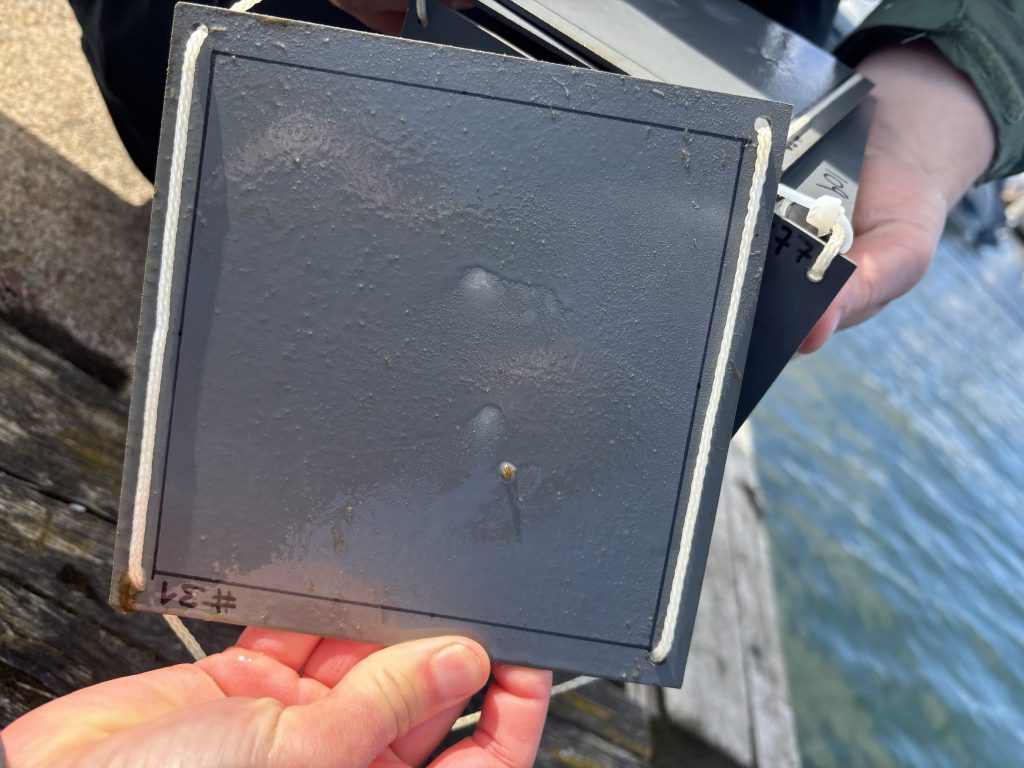

To assess the conditions at the experimental site, we deployed a first set of settlement panels in late April. At first, colonization was slow; only a faint biofilm appeared within two weeks. With the water temperature being still around 7 °C, we decided to give nature more time. Meanwhile, we collected Fucus individuals and practiced the cleaning and the standardizing of the algal thalli for the experiment. Scraping epiphytes off each thallus piece was fiddly, and agreeing on one method was crucial to make sure our results would be comparable to those of other GAME teams.

By early May, building the light setup was a project in itself. Sawing, drilling, testing LEDs, and learning how to secure a 5-meter wooden beam over the water. Our first version bent and twisted until the light pointed sideways instead of straight down onto the algae. Only after buying thicker beams and rebuilding the structure, we finally got a stable and functional setup that could withstand heavy rain and wind. The day we deployed our first experiment at Hamnsundet was cold and rainy but also very rewarding!

Outside of work, we made the most of the island life. We explored Åland by bike, kayak, rowboat, and hiking, visited Ramsholmen National Park during the ramson/ wild garlic bloom, and hiked in Geta with its impressive rock formations and went out boating and fishing in the archipelago. At the station on Husö, cooking became a social event: baking sourdough bread, turning rhubarb from the garden into pies, grilling and making all kind of mushroom dishes. These breaks, in the kitchen and in nature, helped us recharge for the long lab sessions to come.

Every two weeks, it was time to collect and process samples. Snorkeling to the frames, cutting the Fucus and the PVC plates from the lines, and transferring each piece into a freezer bag became our routine. Sampling one experiment took us 4 days and processing all the replicates in the lab easily filled an entire week. The filtering and scraping process was even more time-consuming than we had imagined. It turned out that epiphyte soup is quite thick and clogs filters fastly. This was frustrating at times, since it slowed us down massively.

Over the months, the general community in the water changed drastically. In June, water was still at 10 °C, Fucus carried only a thin layer of diatoms and some very persistent and hard too scrape brown algae (Elachista). In July, everything suddenly exploded: green algae, brown algae, diatoms, cyanobacteria, and tiny zooplankton clogged our filters. With a doubled filtering setup and 6 filtering units, we hoped to compensate for the additional growth.

However, what we had planned as “moderate lab days” turned into marathon sessions. In August, at nearly 20 °C, the Fucus was looking surprisingly clean, but on the PVC a clear winner had emerged. The panels were overrun with the green alga Ulva and looked like the lawn at an abandoned house. Here it was not enough to simply filter the solution, but bigger pieces had to be dried separately. In September, we concluded the last experiment with the help of Sarah from the Cape Verde team, as it was not possible for her to continue on São Vicente, the Cape Verdean island that was most affected by a tropical storm. Our final experiment brought yet another change into community now dominated by brown algae and diatoms. Thankfully our new recruit, sunny autumn weather, and mushroom picking on the side made the last push enjoyable.

By the end of summer, we had accomplished four full experiments. The days were sometimes exhausting but also incredibly rewarding. We learned not only about the ecological effects of artificial light at night, but also about the very practical side of marine research; planning, troubleshooting, and the patience it takes when filtering a few samples can occupy half a day.

Ocean Acidification

What is Coral Bleaching and Why is it Bad News for Coral Reefs?

Coral reefs are beautiful, vibrant ecosystems and a cornerstone of a healthy ocean. Often called the “rainforests of the sea,” they support an extraordinary diversity of marine life from fish and crustaceans to mollusks, sea turtles and more. Although reefs cover less than 1% of the ocean floor, they provide critical habitat for roughly 25% of all ocean species.

Coral reefs are also essential to human wellbeing. These structures reduce the force of waves before they reach shore, providing communities with vital protection from extreme weather such as hurricanes and cyclones. It is estimated that reefs safeguard hundreds of millions of people in more than 100 countries.

What is coral bleaching?

A key component of coral reefs are coral polyps—tiny soft bodied animals related to jellyfish and anemones. What we think of as coral reefs are actually colonies of hundreds to thousands of individual polyps. In hard corals, these tiny animals produce a rigid skeleton made of calcium carbonate (CaCO3). The calcium carbonate provides a hard outer structure that protects the soft parts of the coral. These hard corals are the primary building blocks of coral reefs, unlike their soft coral relatives that don’t secrete any calcium carbonate.

Coral reefs get their bright colors from tiny algae called zooxanthellae. The coral polyps themselves are transparent, and they depend on zooxanthellae for food. In return, the coral polyp provides the zooxanethellae with shelter and protection, a symbiotic relationship that keeps the greater reefs healthy and thriving.

When corals experience stress, like pollution and ocean warming, they can expel their zooxanthellae. Without the zooxanthellae, corals lose their color and turn white, a process known as coral bleaching. If bleaching continues for too long, the coral reef can starve and die.

Ocean warming and coral bleaching

Human-driven stressors, especially ocean warming, threaten the long-term survival of coral reefs. An alarming 77% of the world’s reef areas are already affected by bleaching-level heat stress.

The Great Barrier Reef is a stark example of the catastrophic impacts of coral bleaching. The Great Barrier Reef is made up of 3,000 reefs and is home to thousands of species of marine life. In 2025, the Great Barrier Reef experienced its sixth mass bleaching since 2016. It should also be noted that coral bleaching events are a new thing because of ocean warming, with the first documented in 1998.

Get Ocean Updates in Your Inbox

Sign up with your email and never miss an update.

How you can help

The planet is changing rapidly, and the stakes have never been higher. The ocean has absorbed roughly 90% of the excess heat caused by anthropogenic greenhouse gas emissions, and the consequences, including coral die-offs, are already visible. With just 2℃ of planetary warming, global coral reef losses are estimated to be up to 99% — and without significant change, the world is on track for 2.8°C of warming by century’s end.

To stop coral bleaching, we need to address the climate crisis head on. A recent study from Scripps Institution of Oceanography was the first of its kind to include damage to ocean ecosystems into the economic cost of climate change – resulting in nearly a doubling in the social cost of carbon. This is the first time the ocean was considered in terms of economic harm caused by greenhouse gas emissions, despite the widespread degradation to ocean ecosystems like coral reefs and the millions of people impacted globally.

This is why Ocean Conservancy advocates for phasing out harmful offshore oil and gas and transitioning to clean ocean energy. In this endeavor, Ocean Conservancy also leads international efforts to eliminate emissions from the global shipping industry—responsible for roughly 1 billion tons of carbon dioxide every year.

But we cannot do this work without your help. We need leaders at every level to recognize that the ocean must be part of the solution to the climate crisis. Reach out to your elected officials and demand ocean-climate action now.

The post What is Coral Bleaching and Why is it Bad News for Coral Reefs? appeared first on Ocean Conservancy.

What is Coral Bleaching and Why is it Bad News for Coral Reefs?

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits