With voluntary commitments to cut methane pollution floundering, the prime minister of Barbados urged fellow leaders at the United Nations last month to draw up a “legally binding global agreement” to reduce emissions of the particularly potent greenhouse gas.

Mia Mottley told the UN Secretary-General’s Climate Summit in New York that voluntary efforts like the UAE-led Oil and Gas Decarbonisation Charter – signed by over 50 oil and gas companies – were “not enough” to rein in methane. She said governments should urgently discuss a “no more than two-or-three page agreement on the reduction of methane as a matter of legally binding obligations”.

The Barbadian leader – who has a global reputation for proposing new ideas on climate action and finance – said governments “do not need to reinvent the wheel”. She suggested replicating the 1987 Montreal Protocol that has phased out the production and use of CFC and other gases found in fridges and air conditioners that were responsible for opening a hole in the Earth’s ozone layer.

That protocol put in place legally binding reduction targets for these chemicals, many of which are also greenhouse gases, incentivising government policies to make companies redesign their appliances.

Emissions of ozone-depleting substances have since dropped by almost 100%, and the ozone layer is closing, with Mottley calling it “the most successful climate agreement in history”.

Why focus on methane?

Methane is a short-lived greenhouse gas that is more than 80 times more potent than carbon dioxide (CO2). Experts say cutting methane emissions is a “low-hanging fruit” for tackling global warming, as it would make a big difference with relatively small actions.

Methane emissions come mainly from the agriculture sector (40%), the oil and gas industry (35%) and waste (20%).

Since COP26 in Glasgow, 111 countries have signed up to the Global Methane Pledge – which aims to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030, compared to 2020 levels.

But, in its latest global tracking update in May, the International Energy Agency said methane emissions from fossil fuels remain at stubbornly high levels. Commitments like the pledge have boosted target-setting and momentum, it added, but so far “few countries or companies have formulated real implementation plans for these commitments, and even fewer have demonstrated verifiable emissions reductions”.

Russia justifies fossil gas use by citing contentious COP28 loophole

Mottley told the summit at UN headquarters that tightening regulation on methane emissions made sense for the planet, fossil fuel firms and farmers – and would help buy time in the short-term as countries roll out their national climate plans to cut greenhouse gases across the board.

Her call was backed by French President Emmanuel Macron and Tuvalu’s Prime Minister Feleti Teo, who both said in their speeches that a “binding commitment” on methane is needed. “We know that this is a reachable goal,” Macron said, adding that methane reduction would be a priority when France chairs the G7 next year.

A more difficult challenge than ozone?

But replicating the Montreal Protocol for methane will be challenging. The vast majority of ozone-depleting gases come from a relatively small number of appliances and so could be reduced relatively easily. On the other hand, methane escapes into the atmosphere from a wide variety of sources including belching cows, rice paddies, landfills, leaking gas pipelines, coal mines and oil production facilities.

While some emissions can be prevented cheaply or even profitably – particularly in oil and gas production – others, like those from cows, are more expensive and politically controversial to avoid.

Durwood Zaelke, president of the Institute for Governance and Sustainable Development, has previously campaigned against ozone-depleting substances and is now pushing for methane cuts. He spoke alongside Mottley and Macron at a high-profile meeting on methane in New York in late September.

He told Climate Home News that getting a “coalition of the willing” to agree on methane targets is more likely than persuading all the world’s governments to sign up to an agreement. Countries could make their targets legally binding through their own domestic law, he said.

An international agreement is possible, he added, “but it also can start from the bottom up” if other governments – including sub-national ones like California and Punjab – adopted similar rules to the European Union’s methane regulation.

The EU requires oil and gas companies to detect and repair methane leaks and bans them from burning gas as a waste product in a process known as flaring. It is also imposing increasingly stringent methane intensity standards – opposed by the Trump administration in the US – on imported fossil fuels.

Zaelke said the next step was for Barbados to try and get the rest of the Climate Vulnerable Forum – a group of around 70 Global South countries which it now chairs – and other small island states on board with the idea.

He predicted that methane would have its “moment” at the COP30 climate summit in Brazil, as reduction of non-CO2 gases is one of the 30 objectives of the COP30 presidency’s “action agenda”.

Mottley’s proposal is expected to be discussed at the pre-COP gathering in Brasilia on October 13-14, although opposition from some countries will likely make reaching global consensus very difficult.

Citing comments by UN chief Antonio Guterres that we are on “the highway to climate hell”, Zaelke said: “We’ve got a methane emergency brake. If you pull it and turn the wheel, you can reverse course and slow warming in the near term more than any other way. I think this is becoming clear and so we’ll see the drumbeat for mandatory pick-up.”

The post Mottley’s “legally binding” methane pact faces barriers, but smaller steps possible appeared first on Climate Home News.

Mottley’s “legally binding” methane pact faces barriers, but smaller steps possible

Climate Change

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter.

Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Food inflation on the rise

DELUGE STRIKES FOOD: Extreme rainfall and flooding across the Mediterranean and north Africa has “battered the winter growing regions that feed Europe…threatening food price rises”, reported the Financial Times. Western France has “endured more than 36 days of continuous rain”, while farmers’ associations in Spain’s Andalusia estimate that “20% of all production has been lost”, it added. Policy expert David Barmes told the paper that the “latest storms were part of a wider pattern of climate shocks feeding into food price inflation”.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “Cropped” email newsletter. A fortnightly digest of food, land and nature news and views. Sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

NO BEEF: The UK’s beef farmers, meanwhile, “face a double blow” from climate change as “relentless rain forces them to keep cows indoors”, while last summer’s drought hit hay supplies, said another Financial Times article. At the same time, indoor growers in south England described a 60% increase in electricity standing charges as a “ticking timebomb” that could “force them to raise their prices or stop production, which will further fuel food price inflation”, wrote the Guardian.

‘TINDERBOX’ AND TARIFFS: A study, covered by the Guardian, warned that major extreme weather and other “shocks” could “spark social unrest and even food riots in the UK”. Experts cited “chronic” vulnerabilities, including climate change, low incomes, poor farming policy and “fragile” supply chains that have made the UK’s food system a “tinderbox”. A New York Times explainer noted that while trade could once guard against food supply shocks, barriers such as tariffs and export controls – which are being “increasingly” used by politicians – “can shut off that safety valve”.

El Niño looms

NEW ENSO INDEX: Researchers have developed a new index for calculating El Niño, the large-scale climate pattern that influences global weather and causes “billions in damages by bringing floods to some regions and drought to others”, reported CNN. It added that climate change is making it more difficult for scientists to observe El Niño patterns by warming up the entire ocean. The outlet said that with the new metric, “scientists can now see it earlier and our long-range weather forecasts will be improved for it.”

WARMING WARNING: Meanwhile, the US Climate Prediction Center announced that there is a 60% chance of the current La Niña conditions shifting towards a neutral state over the next few months, with an El Niño likely to follow in late spring, according to Reuters. The Vibes, a Malaysian news outlet, quoted a climate scientist saying: “If the El Niño does materialise, it could possibly push 2026 or 2027 as the warmest year on record, replacing 2024.”

CROP IMPACTS: Reuters noted that neutral conditions lead to “more stable weather and potentially better crop yields”. However, the newswire added, an El Niño state would mean “worsening drought conditions and issues for the next growing season” to Australia. El Niño also “typically brings a poor south-west monsoon to India, including droughts”, reported the Hindu’s Business Line. A 2024 guest post for Carbon Brief explained that El Niño is linked to crop failure in south-eastern Africa and south-east Asia.

News and views

- DAM-AG-ES: Several South Korean farmers filed a lawsuit against the country’s state-owned utility company, “seek[ing] financial compensation for climate-related agricultural damages”, reported United Press International. Meanwhile, a national climate change assessment for the Philippines found that the country “lost up to $219bn in agricultural damages from typhoons, floods and droughts” over 2000-10, according to Eco-Business.

- SCORCHED GRASS: South Africa’s Western Cape province is experiencing “one of the worst droughts in living memory”, which is “scorching grass and killing livestock”, said Reuters. The newswire wrote: “In 2015, a drought almost dried up the taps in the city; farmers say this one has been even more brutal than a decade ago.”

- NOUVELLE VEG: New guidelines published under France’s national food, nutrition and climate strategy “urged” citizens to “limit” their meat consumption, reported Euronews. The delayed strategy comes a month after the US government “upended decades of recommendations by touting consumption of red meat and full-fat dairy”, it noted.

- COURTING DISASTER: India’s top green court accepted the findings of a committee that “found no flaws” in greenlighting the Great Nicobar project that “will lead to the felling of a million trees” and translocating corals, reported Mongabay. The court found “no good ground to interfere”, despite “threats to a globally unique biodiversity hotspot” and Indigenous tribes at risk of displacement by the project, wrote Frontline.

- FISH FALLING: A new study found that fish biomass is “falling by 7.2% from as little as 0.1C of warming per decade”, noted the Guardian. While experts also pointed to the role of overfishing in marine life loss, marine ecologist and study lead author Dr Shahar Chaikin told the outlet: “Our research proves exactly what that biological cost [of warming] looks like underwater.”

- TOO HOT FOR COFFEE: According to new analysis by Climate Central, countries where coffee beans are grown “are becoming too hot to cultivate them”, reported the Guardian. The world’s top five coffee-growing countries faced “57 additional days of coffee-harming heat” annually because of climate change, it added.

Spotlight

Nature talks inch forward

This week, Carbon Brief covers the latest round of negotiations under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which occurred in Rome over 16-19 February.

The penultimate set of biodiversity negotiations before October’s Conference of the Parties ended in Rome last week, leaving plenty of unfinished business.

The CBD’s subsidiary body on implementation (SBI) met in the Italian capital for four days to discuss a range of issues, including biodiversity finance and reviewing progress towards the nature targets agreed under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

However, many of the major sticking points – particularly around finance – will have to wait until later this summer, leaving some observers worried about the capacity for delegates to get through a packed agenda at COP17.

The SBI, along with the subsidiary body on scientific, technical and technological advice (SBSTTA) will both meet in Nairobi, Kenya, later this summer for a final round of talks before COP17 kicks off in Yerevan, Armenia, on 19 October.

Money talks

Finance for nature has long been a sticking point at negotiations under the CBD.

Discussions on a new fund for biodiversity derailed biodiversity talks in Cali, Colombia, in autumn 2024, requiring resumed talks a few months later.

Despite this, finance was barely on the agenda at the SBI meetings in Rome. Delegates discussed three studies on the relationship between debt sustainability and implementation of nature plans, but the more substantive talks are set to take place at the next SBI meeting in Nairobi.

Several parties “highlighted concerns with the imbalance of work” on finance between these SBI talks and the next ones, reported Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

Lim Li Ching, senior researcher at Third World Network, noted that tensions around finance permeated every aspect of the talks. She told Carbon Brief:

“If you’re talking about the gender plan of action – if there’s little or no financial resources provided to actually put it into practice and implement it, then it’s [just] paper, right? Same with the reporting requirements and obligations.”

Monitoring and reporting

Closely linked to the issue of finance is the obligations of parties to report on their progress towards the goals and targets of the GBF.

Parties do so through the submission of national reports.

Several parties at the talks pointed to a lack of timely funding for driving delays in their reporting, according to ENB.

A note released by the CBD Secretariat in December said that no parties had submitted their national reports yet; by the time of the SBI meetings, only the EU had. It further noted that just 58 parties had submitted their national biodiversity plans, which were initially meant to be published by COP16, in October 2024.

Linda Krueger, director of biodiversity and infrastructure policy at the environmental not-for-profit Nature Conservancy, told Carbon Brief that despite the sparse submissions, parties are “very focused on the national report preparation”. She added:

“Everybody wants to be able to show that we’re on the path and that there still is a pathway to getting to 2030 that’s positive and largely in the right direction.”

Watch, read, listen

NET LOSS: Nigeria’s marine life is being “threatened” by “ghost gear” – nets and other fishing equipment discarded in the ocean – said Dialogue Earth.

COMEBACK CAUSALITY: A Vox long-read looked at whether Costa Rica’s “payments for ecosystem services” programme helped the country turn a corner on deforestation.

HOMEGROWN GOALS: A Straits Times podcast discussed whether import-dependent Singapore can afford to shelve its goal to produce 30% of its food locally by 2030.

‘RUSTING’ RIVERS: The Financial Times took a closer look at a “strange new force blighting the [Arctic] landscape”: rivers turning rust-orange due to global warming.

New science

- Lakes in the Congo Basin’s peatlands are releasing carbon that is thousands of years old | Nature Geoscience

- Natural non-forest ecosystems – such as grasslands and marshlands – were converted for agriculture at four times the rate of land with tree cover between 2005 and 2020 | Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- Around one-quarter of global tree-cover loss over 2001-22 was driven by cropland expansion, pastures and forest plantations for commodity production | Nature Food

In the diary

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean | Brasília

- 5 March: Nepal general elections

- 9-20 March: First part of the thirty-first session of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) | Kingston, Jamaica

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz.

Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

Climate Change

Battery passport plan aims to clean up the industry powering clean energy

For millions of consumers, the sustainability scheme stickers found on everything from bananas to chocolate bars and wooden furniture are a way to choose products that are greener and more ethical than some of the alternatives.

Inga Petersen, executive director of the Global Battery Alliance (GBA), is on a mission to create a similar scheme for one of the building blocks of the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy systems: batteries.

“Right now, it’s a race to the bottom for whoever makes the cheapest battery,” Petersen told Climate Home News in an interview.

The GBA is working with industry, international organisations, NGOs and governments to establish a sustainable and transparent battery value chain by 2030.

“One of the things we’re trying to do is to create a marketplace where products can compete on elements other than price,” Petersen said.

Under the GBA’s plan, digital product passports and traceability would be used to issue product-level sustainability certifications, similar to those commonplace in other sectors such as forestry, Petersen said.

Managing battery boom’s risks

Over the past decade, battery deployment has increased 20-fold, driven by record-breaking electric vehicle (EV) sales and a booming market for batteries to store intermittent renewable energy.

Falling prices have been instrumental to the rapid expansion of the battery market. But the breakneck pace of growth has exposed the potential environmental and social harms associated with unregulated battery production.

From South America to Zimbabwe and Indonesia, mineral extraction and refining has led to social conflict, environmental damage, human rights violations and deforestation. In Indonesia, the nickel industry is powered by coal while in Europe, production plants have been met with strong local opposition over pollution concerns.

“We cannot manage these risks if we don’t have transparency,” Petersen said.

The GBA was established in 2017 in response to concerns about the battery industry’s impact as demand was forecast to boom and reports of child labour in the cobalt mines of the Democratic Republic of the Congo made headlines.

The alliance’s initial 19 members recognised that the industry needed to scale rapidly but with “social, environmental and governance guardrails”, said Petersen, who previously worked with the UN Environment Programme to develop guiding principles to minimise the environmental impact of mining.

Digital battery passport

Today, the alliance is working to develop a global certification scheme that will recognise batteries that meet minimum thresholds across a set of environmental, social and governance benchmarks it has defined along the entire value chain.

Participating mines, manufacturing plants and recycling facilities will have to provide data for their greenhouse gas emissions as well as how they perform against benchmarks for assessing biodiversity loss, pollution, child and forced labour, community impacts and respect for the rights of Indigenous peoples, for example.

The data will be independently verified, scored, aggregated and recorded on a battery passport – a digital record of the battery’s composition, which will include the origin of its raw materials and its performance against the GBA’s sustainability benchmarks.

The scheme is due to launch in 2027.

A carrot and a stick

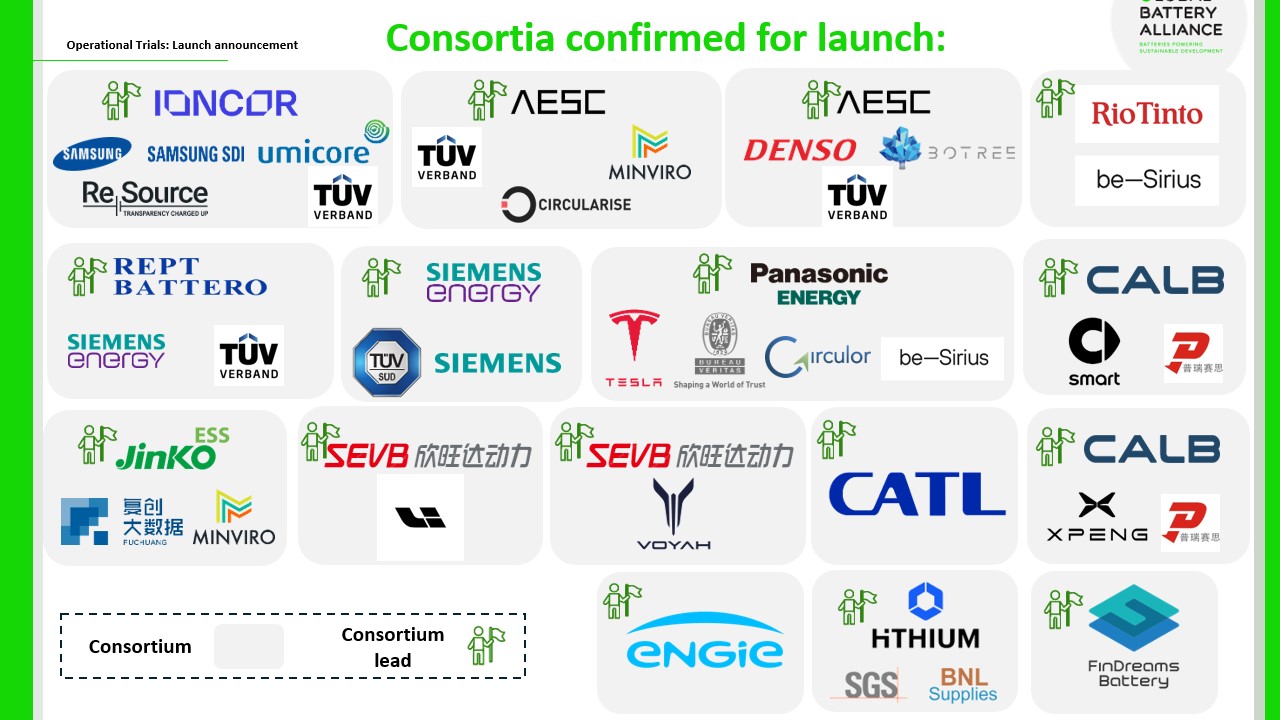

Since the start of the year, some of the world’s largest battery companies have been voluntarily participating in the biggest pilot of the scheme to date.

More than 30 companies across the EV battery and stationary storage supply chains are involved, among them Chinese battery giants CATL and BYD subsidiary FinDreams Battery, miner Rio Tinto, battery producers Samsung SDI and Siemens, automotive supplier Denso and Tesla.

Petersen said she was “thrilled” about support for the scheme. Amid a growing pushback against sustainability rules and standards, “these companies are stepping up to send a public signal that they are still committed to a sustainable and responsible battery value chain,” she said.

There are other motivations for battery producers to know where components in their batteries have come from and whether they have been produced responsibly.

In 2023, the EU adopted a law regulating the batteries sold on its market.

From 2027, it mandates all batteries to meet environmental and safety criteria and to have a digital passport accessed via a QR code that contains information about the battery’s composition, its carbon footprint and its recycling content.

The GBA certification is not intended as a compliance instrument for the EU law but it will “add a carrot” by recognising manufacturers that go beyond meeting the bloc’s rules on nature and human rights, Petersen said.

Raising standards in complex supply chain

But challenges remain, in part due to the complexity of battery supply chains.

In the case of timber, “you have a single input material but then you have a very complex range of end products. For batteries, it’s almost the reverse,” Petersen said.

The GBA wants its certification scheme to cover all critical minerals present in batteries, covering dozens of different mining, processing and manufacturing processes and hundreds of facilities.

“One of the biggest impacts will be rewarding the leading performers through preferential access to capital, for example, with investors choosing companies that are managing their risk responsibly and transparently,” Petersen said.

It could help influence public procurement and how companies, such as EV makers, choose their suppliers, she added. End consumers will also be able to access a summary of the GBA’s scores when deciding which product to buy.

US, Europe rush to build battery supply chain

Today, the GBA has more than 150 members across the battery value chain, including more than 50 companies, of which over a dozen are Chinese firms.

China produces over three-quarters of batteries sold globally and it dominates the world’s battery recycling capacity, leaving the US and Europe scrambling to reduce their dependence on Beijing by building their own battery supply chains.

Petersen hopes the alliance’s work can help build trust in the sector amid heightened geopolitical tensions. “People want to know where the materials are coming from and which actors are involved,” she said.

At the same time, companies increasingly recognise that failing to manage sustainability risks can threaten their operations. Protests over environmental concerns have shut down mines and battery factories across the world.

“Most companies know that and that’s why they’re making these efforts,” Petersen added.

The post Battery passport plan aims to clean up the industry powering clean energy appeared first on Climate Home News.

Battery passport plan aims to clean up the industry powering clean energy

Climate Change

Reheating plastic food containers: what science says about microplastics and chemicals in ready meals

How often do you eat takeaway food? What about pre-prepared ready meals? Or maybe just microwaving some leftovers you had in the fridge? In any of these cases, there’s a pretty good chance the container was made out of plastic. Considering that they can be an extremely affordable option, are there any potential downsides we need to be aware of? We decided to investigate.

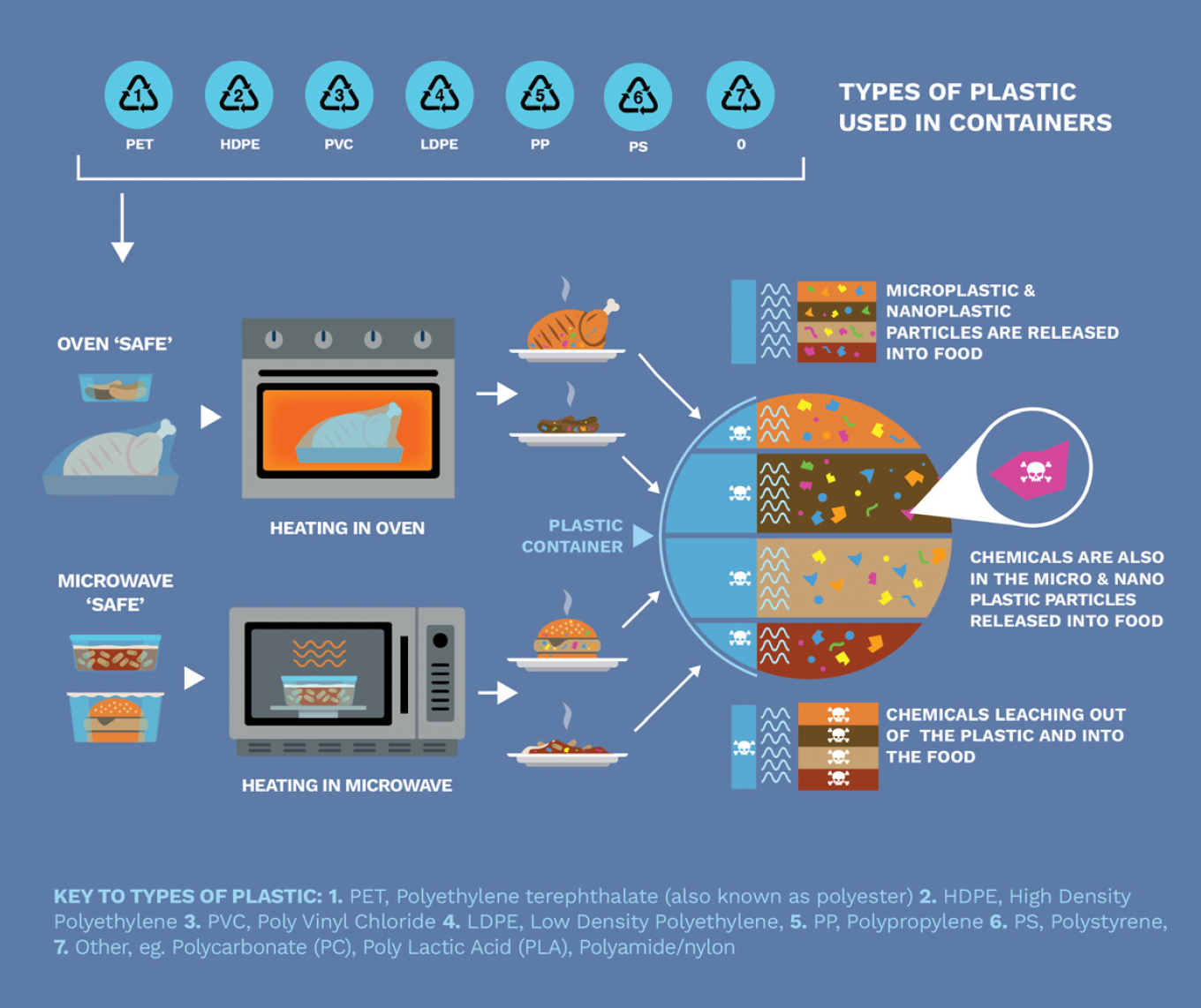

Scientific research increasingly shows that heating food in plastic packaging can release microplastics and plastic chemicals into the food we eat. A new Greenpeace International review of peer-reviewed studies finds that microwaving plastic food containers significantly increases this release, raising concerns about long-term human health impacts. This article summarises what the science says, what remains uncertain, and what needs to change.

There’s no shortage of research showing how microplastics and nanoplastics have made their way throughout the environment, from snowy mountaintops and Arctic ice, into the beetles, slugs, snails and earthworms at the bottom of the food chain. It’s a similar story with humans, with microplastics found in blood, placenta, lungs, liver and plenty of other places. On top of this, there’s some 16,000 chemicals known to be either present or used in plastic, with a bit over a quarter of those chemicals already identified as being of concern. And there are already just under 1,400 chemicals that have been found in people.

Not just food packaging, but plenty of household items either contain or are made from plastic, meaning they potentially could be a source of exposure as well. So if microplastics and chemicals are everywhere (including inside us), how are they getting there? Should we be concerned that a lot of our food is packaged in plastic?

Greenpeace analysis of 24 articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals found that the plastics we use to package our food are directly risking our health.

Heating food in plastic packaging dramatically increases the levels of microplastics and chemicals that leach into our food.

Plastic food packaging: the good, the bad, and the ugly

The growing trend towards ready meals, online shopping and restaurant delivery, and away from home-prepared meals and individual grocery shopping, is happening in every region of the world. Since the first microwaveable TV dinners were introduced in the US in the 1950s to sell off excess stock of turkey meat after Thanksgiving holidays, pre-packaged ready meals have grown hugely in sales. The global market is worth $190bn in 2025, and is expected to reach a total volume of 71.5 million tonnes by 2030. It’s also predicted that the top five global markets for convenience food (China, USA, Japan, Mexico and Russia) will remain relatively unchanged up to 2030, with the most revenue in 2019 generated by the North America region.

A new report from Greenpeace International set out to analyse articles in peer-reviewed, scientific journals to look at what exactly the research has to say about plastic food packaging and food contact plastics.

Here’s what we found.

Our review of 24 recent articles highlights a consistent picture that regulators, businesses and

consumers should be concerned about: when food is packaged in plastic and then microwaved, this significantly increases the risk of both microplastic and chemical release, and that these microplastics and chemicals will leach into the food inside the packaging.

And not just some, but a lot of microplastics and chemicals.

When polystyrene and polypropylene containers filled with water were microwaved after being stored in the fridge or freezer, one study found they released anywhere between 100,000-260,000 microplastic particles, and another found that five minutes of microwave heating could release between 326,000-534,000 particles into food.

Similarly there are a wide range of chemicals that can be and are released when plastic is heated. Across different plastic types, there are estimated to be around 16,000 different chemicals that can either be used or present in plastics, and of these around 4,200 are identified as being hazardous, whilst many others lack any form of identification (hazardous or otherwise) at all.

The research also showed that 1,396 food contact plastic chemicals have been found in humans, several of which are known to be hazardous to human health. At the same time, there are many chemicals for which no research into the long-term effects on human health exists.

Ultimately, we are left with evidence pointing towards increased release of microplastics and plastic chemicals into food from heating, the regular migration of microplastics and chemicals into food, and concerns around what long-term impacts these substances have on human health, which range from uncertain to identified harm.

The known unknowns of plastic chemicals and microplastics

The problem here (aside from the fact that plastic chemicals are routinely migrating into our food), is that often we don’t have any clear research or information on what long-term impacts these chemicals have on human health. This is true of both the chemicals deliberately used in plastic production (some of which are absolutely toxic, like antimony which is used to make PET plastic), as well as in what’s called non-intentionally added substances (NIAS).

NIAS refers to chemicals which have been found in plastic, and typically originate as impurities, reaction by-products, or can even form later when meals are heated. One study found that a UV stabiliser plastic additive reacted with potato starch when microwaved to create a previously unknown chemical compound.

We’ve been here before: lessons from tobacco, asbestos and lead

Although none of this sounds particularly great, this is not without precedence. Between what we do and don’t know, waiting for perfect evidence is costly both economically and in terms of human health. With tobacco, asbestos, and lead, a similar story to what we’re seeing now has played out before. After initial evidence suggesting problems and toxicity, lobbyists from these industries pushed back to sow doubt about the scientific validity of the findings, delaying meaningful action. And all the while, between 1950-2000, tobacco alone led to the deaths of around 60 million people. Whilst distinguishing between correlation and causation, and finding proper evidence is certainly important, it’s also important to take preventative action early, rather than wait for more people to be hurt in order to definitively prove the point.

Where to from here?

This is where adopting the precautionary principle comes in. This means shifting the burden of proof away from consumers and everyone else to prove that a product is definitely harmful (e.g. it’s definitely this particular plastic that caused this particular problem), and onto the manufacturer to prove that their product is definitely safe. This is not a new idea, and plenty of examples of this exist already, such as the EU’s REACH regulation, which is centred around the idea of “no data, no market” – manufacturers are obligated to provide data demonstrating the safety of their product in order to be sold.

Greenpeace analysis of 24 articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals found that the plastics we use to package our food are directly risking our health.

Heating food in plastic packaging dramatically increases the levels of microplastics and chemicals that leach into our food.

But as it stands currently, the precautionary principle isn’t applied to plastics. For REACH in particular, plastics are assessed on a risk-based approach, which means that, as the plastic industry itself has pointed out, something can be identified as being extremely hazardous, but is still allowed to be used in production if the leached chemical stays below “safe” levels, despite that for some chemicals a “safe” low dose is either undefined, unknown, or doesn’t exist.

A better path forward

Governments aren’t acting fast enough to reduce our exposure and protect our health. There’s no shortage of things we can do to improve this situation. The most critical one is to make and consume less plastic. This is a global problem that requires a strong Global Plastics Treaty that reduces global plastic production by at least 75% by 2040 and eliminates harmful plastics and chemicals. And it’s time that corporations take this growing threat to their customers’ health seriously, starting with their food packaging and food contact products. Here are a number of specific actions policymakers and companies can take, and helpful hints for consumers.

Policymakers & companies

- Implement the precautionary principle:

- For policymakers – Stop the use of hazardous plastics and chemicals, on the basis of their intrinsic risk, rather than an assessment of “safe” levels of exposure.

- For companies – Commit to ensure that there is a “zero release” of microplastics and hazardous chemicals from packaging into food, alongside an Action Plan with milestones to achieve this by 2035

- Stop giving false assurances to consumers about “microwave safe” containers

- Stop the use of single-use and plastic packaging, and implement policies and incentives to foster the uptake of reuse systems and non-toxic packaging alternatives.

Consumers

- Encourage your local supermarkets and shops to shift away from plastic where possible

- Avoid using plastic containers when heating/reheating food

- Use non-plastic refill containers

Trying to dodge plastic can be exhausting. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, you’re not alone. We can only do so much in this broken plastic-obsessed system. Plastic producers and polluters need to be held accountable, and governments need to act faster to protect the health of people and the planet. We urgently need global governments to accelerate a justice-centred transition to a healthier, reuse-based, zero-waste future. Ensure your government doesn’t waste this once-in-a-generation opportunity to end the age of plastic.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits