India’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from its power sector fell by 1% year-on-year in the first half of 2025 and by 0.2% over the past 12 months, only the second drop in almost half a century.

As a result, India’s CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and cement grew at their slowest rate in the first half of the year since 2001 – excluding Covid – according to new analysis for Carbon Brief.

The analysis is the first of a regular new series covering India’s CO2 emissions, based on monthly data for fuel use, industrial production and power output, compiled from numerous official sources.

(See the regular series on China’s CO2 emissions, which began in 2019.)

Other key findings on India for the first six months of 2025 include:

- The growth in clean-energy capacity reached a record 25.1 gigawatts (GW), up 69% year-on-year from what had, itself, been a record figure.

- This new clean-energy capacity is expected to generate nearly 50 terawatt hours (TWh) of electricity per year, nearly sufficient to meet the average increase in demand overall.

- Slower economic expansion meant there was zero growth in demand for oil products, a marked fall from annual rates of 6% in 2023 and 4% in 2024.

- Government infrastructure spending helped accelerate CO2 emissions growth from steel and cement production, by 7% and 10%, respectively.

The analysis also shows that emissions from India’s power sector could peak before 2030, if clean-energy capacity and electricity demand grow as expected.

The future of CO2 emissions in India is a key indicator for the world, with the country – the world’s most populous – having contributed nearly two-fifths of the rise in global energy-sector emissions growth since 2019.

India’s surging emissions slow down

In 2024, India was responsible for 8% of global energy-sector CO2 emissions, despite being home to 18% of the world’s population, as its per-capita output is far below the world average.

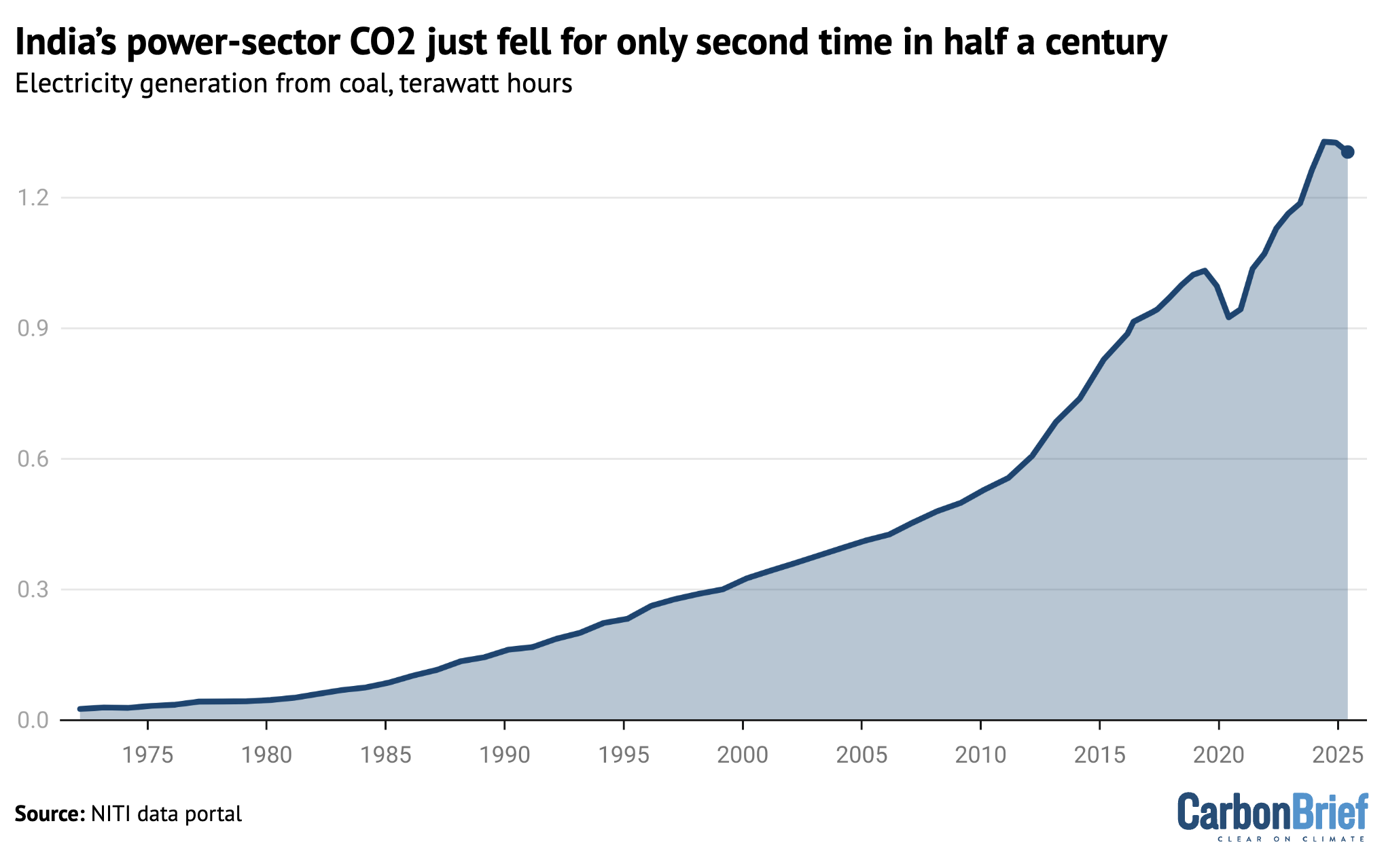

However, emissions have been growing rapidly, as shown in the figure below.

The country contributed 31% of global energy-sector emissions growth in the decade to 2024, rising to 37% in the past five years, due to a surge in the three-year period from 2021-23.

More than half of India’s CO2 output comes from coal used for electricity and heat generation, making this sector the most important by far for the country’s emissions.

The second-largest sector is fossil fuel use in industry, which accounts for another quarter of the total, while oil use for transport makes up a further eighth of India’s emissions.

India’s CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and cement grew by 8% per year from 2019 to 2023, quickly rebounding from a 7% drop in 2020 due to Covid.

Before the Covid pandemic, emissions growth had averaged 4% per year from 2010 to 2019, but emissions in 2023 and 2024 rose above the pre-pandemic trendline.

This was despite a slower average GDP growth rate from 2019 to 2024 than in the preceding decade, indicating that the economy became more energy- and carbon-intensive. (For example, growth in steel and cement outpaced the overall rate of economic growth.)

A turnaround came in the second half of 2024, when emissions only increased by 2% year-on-year, slowing down to 1% in the first half of 2025, as seen in the figure below.

The largest contributor to the slowdown was the power sector, which was responsible for 60% of the drop in emissions growth rates, when comparing the first half of 2025 with the years 2021-23.

Oil demand growth slowed sharply as well, contributing 20% of the slowdown. The only sectors to keep growing their emissions in the first half of 2025 were steel and cement production.

Another 20% of the slowdown was due to a reduction in coal and gas use outside the power, steel and cement sectors. This comprises construction, industries such as paper, fertilisers, chemicals, brick kilns and textiles, as well as residential and commercial cooking, heating and hot water.

This is all shown in the figure below, which compares year-on-year changes in emissions during the second half of 2024 and the first half of 2025, with the average for 2021-23.

Power sector emissions fell by 1% in the first half of 2025, after growing 10% per year during 2021-23 and adding more than 50m tonnes of CO2 (MtCO2) to India’s total every six months.

Oil product use saw zero growth in the first half of 2025, after rising 6% per year in 2021-23.

In contrast, emissions from coal burning for cement and steel production rose by 10% and 7%, respectively, while coal use outside of these sectors fell 2%.

Gas consumption fell 7% year-on-year, with reductions across the power and industrial sectors as well as other users. This was a sharp reversal of the 5% average annual growth in 2021-23.

Power-sector emissions pause

The most striking shift in India’s sectoral emissions trends has come in the power sector, where coal consumption and CO2 emissions fell 0.2% in the 12 months to June and 1% in the first half of 2025, marking just the second drop in half a century, as shown in the figure below.

The reduction in coal use comes after more than a decade of break-neck growth, starting in the early 2010s and only interrupted by Covid in 2020. It also comes even as the country plans large amounts of new coal-fired generating capacity.

In the first half of 2025, total power generation increased by 9 terawatt hours (TWh) year-on-year, but fossil power generation fell by 29TWh, as output from solar grew 17TWh, from wind 9TWh, from hydropower by 9TWh and from nuclear by 3TWh.

Analysis of government data shows that 65% of the fall in fossil-fuel generation can be attributed to lower electricity demand growth, 20% to faster growth in non-hydro clean power and the remaining 15% to higher output at existing hydropower plants.

Slower growth in electricity usage was largely due to relatively mild temperatures and high rainfall, in contrast to the heatwaves of 2024. A slowdown in industrial sectors in the second quarter of the year also contributed.

In addition, increased rainfall drove the jump in hydropower generation. India received 42% above-normal rainfall from March to May 2025. (In early 2024, India’s hydro output had fallen steeply as a result of “erratic rainfall”.)

Lower temperatures and this abundant rainfall reduced the need for air conditioning, which is responsible for around 10% of the country’s total power demand. In the same period in 2024, demand surged due to record heatwaves and higher temperatures across the country.

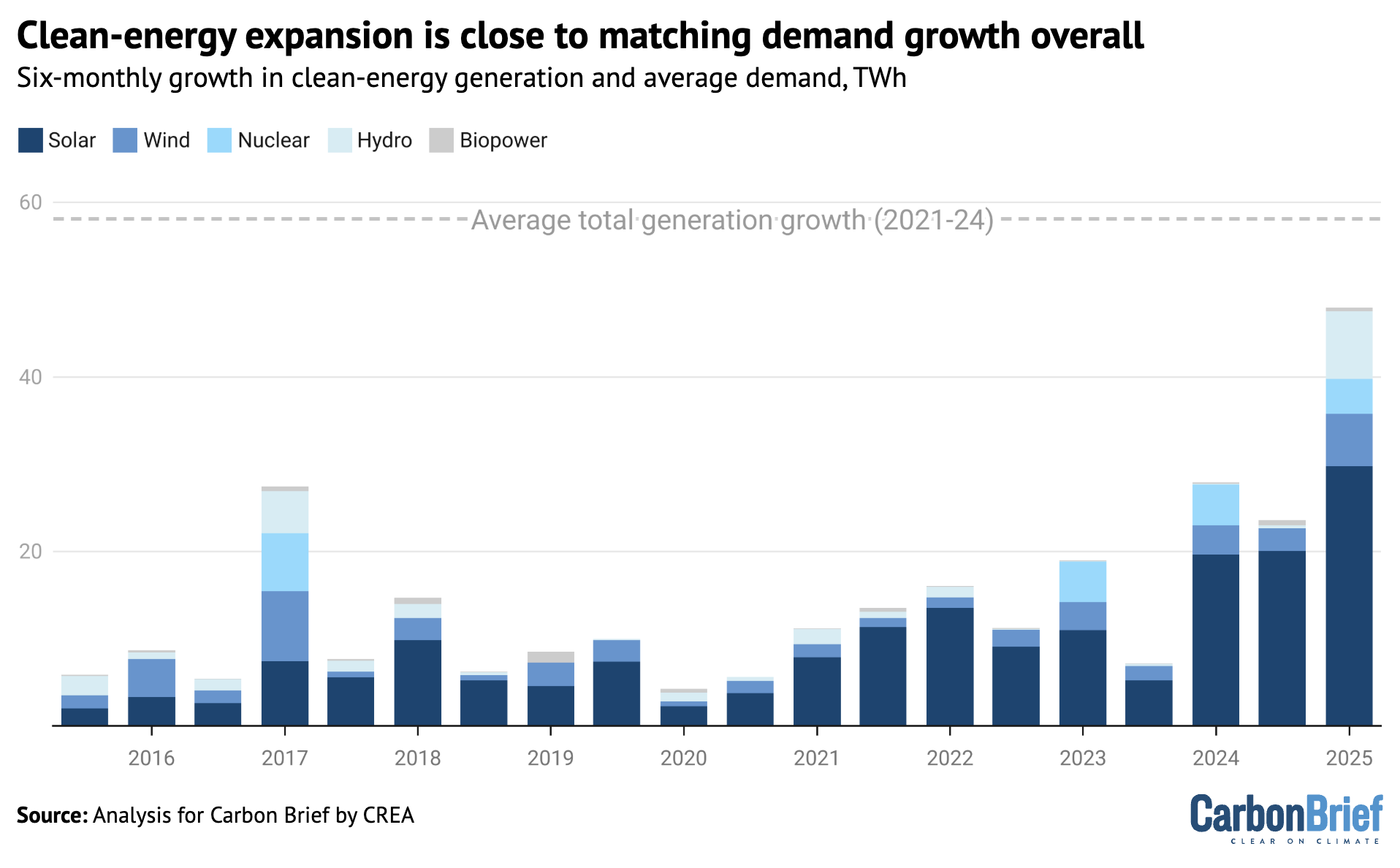

The growth in clean-power generation was buoyed by the addition of a record 25.1GW of non-fossil capacity in the first half of 2025. This was a 69% increase compared with the previous period in 2024, which had also set a record.

Solar continues to dominate new installations, with 14.3GW of capacity added in the first half of the year coming from large scale solar projects and 3.2GW from solar rooftops.

Solar is also adding the majority of new clean-power output. Taking into account the average capacity factor of each technology, solar power delivered 62% of the additional annual generation, hydropower 16%, wind 13% and nuclear power 8%.

The new clean-energy capacity added in the first half of 2025 will generate record amounts of clean power. As shown in the figure below, the 50TWh per year from this new clean capacity is approaching the average growth of total power generation.

(When clean-energy growth exceeds total demand growth, generation from fossil fuels declines.)

India is expected to add another 16-17GW of solar and wind in the second half of 2025. Beyond this year, strong continued clean-energy growth is expected, towards India’s target for 500GW of non-fossil fuel capacity by 2030 (see below).

Slowing oil demand growth

The first half of 2025 also saw a significant slowdown in India’s oil demand growth. After rising by 6% a year in the three years to 2023, it slowed to 4% in 2024 and zero in the first half of 2025.

The slowdown in oil consumption overall was predominantly due to slower growth in demand for diesel and “other oil products”, which includes bitumen.

In the first quarter of 2025, diesel demand actually fell, due to a decline in industrial activity, limited weather-related mobility and – reportedly – higher uptake of vehicles that run on compressed natural gas (CNG), as well as electricity (EVs).

Diesel demand growth increased in March to May, but again declined in June because of early and unusually severe monsoon rains in India, leading to a slowdown in industrial and mining activities, disrupted supply-chains and transport of raw material, goods and services.

The severe rains also slowed down road construction activity, which in turn curtailed demand for transportation, construction equipment and bitumen.

Weaker diesel demand growth in 2024 had reflected slower growth in economic activity, as growth rates in the industrial and agricultural sectors contracted compared to previous years.

Another important trend is that EVs are also cutting into diesel demand in the commercial vehicles segment, although this is not yet a significant factor in the overall picture.

EV adoption is particularly notable in major metropolitan cities and other rapidly emerging urban centres and in the logistics sector, where they are being preferred for short haul rides over diesel vans or light commercial vehicles.

EVs accounted for only 7.6% of total vehicle sales in the financial year 2024-25, up 22.5% year-on-year, but still far from the target of 30% by 2030.

However, any significant drop in diesel demand will be a function of adoption of EV for long-haul trucks, which account for 32% of the total CO2 emissions from the transport sector. Only 280 electric trucks were sold in 2024, reported NITI Aayog.

Trucks remain the largest diesel consumers. Moreover, truck sales grew 9.2% year-on-year in the second quarter of 2025, driven in part by India’s target of 75% farm mechanisation by 2047. This sales growth may outweigh the reduction in diesel demand due to EVs. Subsidies for electric tractors have seen some pilots, but demand is yet to take off.

Apart from diesel, petrol demand growth continued in the first half of 2025 at the same rate as in earlier years. Modest year-on-year growth of 1.3% in passenger vehicle sales could temper future increases in petrol demand, however. This is a sharp decline from 7.5% and 10% growth rates in sales in the same period in 2024 and 2023.

Furthermore, EVs are proving to be cheaper to run than petrol for two- and three-wheelers, which may reduce the sale of petrol vehicles in cities that show policy support for EV adoption.

Steel and cement emissions continue to grow

As already noted, steel and cement were the only major sectors of India’s economy to see an increase in emissions growth in the first half of 2025.

While they were only responsible for around 12% of India’s total CO2 emissions from fossil fuels and cement in 2024, they have been growing quickly, averaging 6% a year for the past five years.

The growth in emissions accelerated in the first half of 2025, as cement output rose 10% and steel output 7%, far in excess of the growth in economic output overall.

Steel and cement growth accelerated further in July. A key demand driver is government infrastructure spending, which tripled from 2019 to 2024.

In the second quarter of 2025, the government’s capital expenditure increased 52% year-on-year. albeit from a low base during last year’s elections. This signals strong growth in infrastructure.

The government is targeting domestic steel manufacturing capacity of 300m tonnes (Mt) per year by 2030, from 200Mt currently, under the National Steel Policy 2017, supported by financial incentives for firms that meet production targets for high quality steel.

The government also imposed tariffs on steel imports in April and stricter quality standards for imports in June, in order to boost domestic production.

Government policies such as Pradhan Mantri Awas Yojna – a “housing for all” initiative under which 30m houses are to be built by FY30 – is further expected to lift demand for steel and cement.

The automotive sector in India is expected to grow at a fast pace, with sales expected to reach 7.5m units for passenger vehicle and commercial vehicle segments from 5.1m units in 2023, in addition to rapid growth in electric vehicles. This can be expected to be another key driver for growth of the steel sector, as 900 kg of steel is used per vehicle.

Without stringent energy efficiency measures and the adoption of cleaner fuel, the expected growth in steel and cement production could drive significant emissions growth from the sector.

Power-sector emissions could peak before 2030

Looking beyond this year, the analysis shows that CO2 from India’s power sector could peak before 2030, having previously been the main driver of emissions growth.

To date, India’s clean-energy additions have been lagging behind the growth in total electricity demand, meaning fossil-fuel demand and emissions from the sector have continued to rise.

However, this dynamic looks likely to change. In 2021, India set a target of having 500GW of non-fossil power generation capacity in place by 2030. Progress was slow at first, so meeting the target implies a substantial acceleration in clean-energy additions.

The country has been laying the groundwork for such an acceleration.

There was 234GW of renewable capacity in the pipeline as of April 2025, according to the Ministry of New and Renewable Energy. This includes 169GW already awarded contracts, of which 145GW is under construction, and an additional 65GW put out to tender. There is also 5.2GW of new nuclear capacity under construction.

If all of this is commissioned by 2030, then total non-fossil capacity would increase to 482GW, from 243GW at the end of June 2025, leaving a gap of just 18GW to be filled with new projects.

When the non-fossil capacity target was set in 2021, CREA assessed that the target would suffice to peak demand for coal in power generation before 2030. This assessment remains valid and is reinforced by the latest Central Electricity Authority (CEA) projection for the country’s “optimal power mix” in 2030, shown in the figure below.

In the CEA’s projection, the share of non-fossil power generation rises to 44% in the 2029-30 fiscal year, up from 25% in 2024-25. From 2025 to 2030, power demand growth, averaging 6% per year, is entirely covered from clean sources.

To accomplish this, the growth in non-fossil power generation would need to accelerate over time, meaning that towards the end of the decade, the growth in clean power supply would clearly outstrip demand growth overall – and so power generation from fossil fuels would fall.

While coal-power generation is expected to flatline, large amounts of new coal-power capacity is still being planned, because of the expected growth in peak electricity demand.

The post-Covid increase in electricity demand has given rise to a wave of new coal power plant proposals. Recent plans from the government target an increase in coal-power capacity by another 80-100GW by 2030-32, with 35GW already under construction as of July 2025.

The rationale for this is the increase in peak electricity loads, associated in particular with worsening heatwaves and growing use of air conditioning. The increase might yet prove unneeded.

Analysis by CREA shows that solar and wind are making an increasing contribution to meeting peak loads. This contribution will increase with the roll-out of solar power with integrated battery storage, the cost of which fell by 50-60% from 2023 to 2025.

The latest auction held in India saw solar power with battery storage bidding at prices, per unit of electricity generation, that were lower than the cost of new coal power.

This creates the opportunity to accelerate the decarbonisation of India’s power sector, by reducing the need for thermal power capacity.

The clean-energy buildout has made it possible for India to peak its power-sector emissions within the next few years, if contracted projects are built, clean-energy growth is maintained or accelerated beyond 2030 and demand growth remains within the government’s projections.

This would be a major turning point, as the power sector has been responsible for half of India’s recent emissions growth. In order to peak its emissions overall, however, India would still need to take further action to address CO2 from industry and transport.

With the end-of-September 2025 deadline nearing, India has yet to publish its international climate pledge (nationally determined contribution, NDC) for 2035 under the Paris Agreement, meaning its future emissions path, in the decades up to its 2070 net-zero goal, remains particularly uncertain.

The country is expected to easily surpass the headline climate target from its previous NDC, of cutting the emissions intensity of its economy to 45% below 2005 levels by 2030. As such, this goal is “unlikely to drive real world emission reductions”, according to Climate Action Tracker.

In July of this year, it met a 2030 target for 50% of installed power generating capacity to be from non-fossil sources, five years early.

About the data

This analysis is based on official monthly data for fuel consumption, industrial production and power generation from different ministries and government institutes.

Coal consumption in thermal power plants is taken from the monthly reports downloaded from the National Power Portal of the Ministry of Power. The data is compiled for the period January 2019 until June 2025. Power generation and capacity by technology and fuel on a monthly basis are sourced from the NITI data portal.

Coal use at steel and cement plants, as well as process emissions from cement production, are estimated using production indices from the Index of Eight Core Industries released monthly by the Office of Economic Adviser, assuming that changes in emissions follow production volumes.

These production indices were used to scale coal use by the sectors in 2022. To form a basis for using the indices, monthly coal consumption data for 2022 was constructed for the sectors using the annual total coal consumption reported in IEA World Energy Balances and monthly production data in a paper by Robbie Andrew, on monthly CO2 emission accounting for India.

Annual cement process emissions up to 2024 were also taken from Robbie Andrew’s work and scaled using the production indices. This approach better approximated changes in energy use and emissions reported in the IEA World Energy Balances, than did the amounts of coal reported to have been dispatched to the sectors, showing that production volumes are the dominant driver of short-term changes in emissions.

For other sectors, including aluminium, auto, chemical and petrochemical, paper and plywood, pharmaceutical, graphite electrode, sugar, textile, mining, traders and others, coal consumption is estimated based on data on despatch of domestic and imported coal to end users from statistical reports and monthly reports by the Ministry of Coal, as consumption data is not available.

The difference between consumption and dispatch is stock changes, which are estimated by assuming that the changes in coal inventories at end user facilities mirror those at coal mines, with end user inventories excluding power, steel and cement assumed to be 70% of those at coal mines, based on comparisons between our data and the IEA World Energy Balances.

Stock changes at mines are estimated as the difference between production at and despatch from coal mines, as reported by the Ministry of Coal.

In the case of the second quarter of the year 2025, data on domestic coal has been taken from the monthly reports by the Ministry of Coal. The regular data releases on coal imports have not taken place for the second quarter of 2025, for unknown reasons, so data was taken from commercial data providers Coal Hub and mjunction services ltd.

Product-wise petroleum product consumption data, as well as gas use by sector, was downloaded from the Petroleum Planning and Analysis Cell of the Ministry of Petroleum & Natural Gas.

As the fuel dispatch and consumption data is reported as physical volumes, calorific values are taken from IEA’s World Energy Balance and CO2 emission factors from 2006 IPCC Guidelines for National Greenhouse Gas Inventories.

Calorific values are assigned separately to different fuel types, including domestic and imported coal, anthracite and coke, as well as petrol, diesel and several other oil products.

The post Analysis: India’s power-sector CO2 falls for only second time in half a century appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: India’s power-sector CO2 falls for only second time in half a century

Climate Change

Whale Entanglements in Fishing Gear Surge Off U.S. West Coast During Marine Heatwaves

New research finds that rising ocean temperatures are shrinking cool-water feeding grounds, pushing humpbacks into gear-heavy waters near shore. Scientists say ocean forecasting tool could help fisheries reduce the risk.

Each spring, humpback whales start to feed off the coast of California and Oregon on dense schools of anchovies, sardines and krill—prey sustained by cool, nutrient-rich water that seasonal winds draw up from the deep ocean.

Whale Entanglements in Fishing Gear Surge Off U.S. West Coast During Marine Heatwaves

Climate Change

Grasslands and Wetlands Are Being Gobbled Up By Agriculture, Mostly Livestock

A new study takes a first-of-its kind look at how farming converts non-forested areas and major carbon sinks into cropland and pasture.

Agriculture is widely known to be the biggest driver of forest destruction globally, especially in sprawling, high-profile ecosystems like the Amazon rainforest.

Grasslands and Wetlands Are Being Gobbled Up By Agriculture, Mostly Livestock

Climate Change

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter.

Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Food inflation on the rise

DELUGE STRIKES FOOD: Extreme rainfall and flooding across the Mediterranean and north Africa has “battered the winter growing regions that feed Europe…threatening food price rises”, reported the Financial Times. Western France has “endured more than 36 days of continuous rain”, while farmers’ associations in Spain’s Andalusia estimate that “20% of all production has been lost”, it added. Policy expert David Barmes told the paper that the “latest storms were part of a wider pattern of climate shocks feeding into food price inflation”.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “Cropped” email newsletter. A fortnightly digest of food, land and nature news and views. Sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

NO BEEF: The UK’s beef farmers, meanwhile, “face a double blow” from climate change as “relentless rain forces them to keep cows indoors”, while last summer’s drought hit hay supplies, said another Financial Times article. At the same time, indoor growers in south England described a 60% increase in electricity standing charges as a “ticking timebomb” that could “force them to raise their prices or stop production, which will further fuel food price inflation”, wrote the Guardian.

‘TINDERBOX’ AND TARIFFS: A study, covered by the Guardian, warned that major extreme weather and other “shocks” could “spark social unrest and even food riots in the UK”. Experts cited “chronic” vulnerabilities, including climate change, low incomes, poor farming policy and “fragile” supply chains that have made the UK’s food system a “tinderbox”. A New York Times explainer noted that while trade could once guard against food supply shocks, barriers such as tariffs and export controls – which are being “increasingly” used by politicians – “can shut off that safety valve”.

El Niño looms

NEW ENSO INDEX: Researchers have developed a new index for calculating El Niño, the large-scale climate pattern that influences global weather and causes “billions in damages by bringing floods to some regions and drought to others”, reported CNN. It added that climate change is making it more difficult for scientists to observe El Niño patterns by warming up the entire ocean. The outlet said that with the new metric, “scientists can now see it earlier and our long-range weather forecasts will be improved for it.”

WARMING WARNING: Meanwhile, the US Climate Prediction Center announced that there is a 60% chance of the current La Niña conditions shifting towards a neutral state over the next few months, with an El Niño likely to follow in late spring, according to Reuters. The Vibes, a Malaysian news outlet, quoted a climate scientist saying: “If the El Niño does materialise, it could possibly push 2026 or 2027 as the warmest year on record, replacing 2024.”

CROP IMPACTS: Reuters noted that neutral conditions lead to “more stable weather and potentially better crop yields”. However, the newswire added, an El Niño state would mean “worsening drought conditions and issues for the next growing season” to Australia. El Niño also “typically brings a poor south-west monsoon to India, including droughts”, reported the Hindu’s Business Line. A 2024 guest post for Carbon Brief explained that El Niño is linked to crop failure in south-eastern Africa and south-east Asia.

News and views

- DAM-AG-ES: Several South Korean farmers filed a lawsuit against the country’s state-owned utility company, “seek[ing] financial compensation for climate-related agricultural damages”, reported United Press International. Meanwhile, a national climate change assessment for the Philippines found that the country “lost up to $219bn in agricultural damages from typhoons, floods and droughts” over 2000-10, according to Eco-Business.

- SCORCHED GRASS: South Africa’s Western Cape province is experiencing “one of the worst droughts in living memory”, which is “scorching grass and killing livestock”, said Reuters. The newswire wrote: “In 2015, a drought almost dried up the taps in the city; farmers say this one has been even more brutal than a decade ago.”

- NOUVELLE VEG: New guidelines published under France’s national food, nutrition and climate strategy “urged” citizens to “limit” their meat consumption, reported Euronews. The delayed strategy comes a month after the US government “upended decades of recommendations by touting consumption of red meat and full-fat dairy”, it noted.

- COURTING DISASTER: India’s top green court accepted the findings of a committee that “found no flaws” in greenlighting the Great Nicobar project that “will lead to the felling of a million trees” and translocating corals, reported Mongabay. The court found “no good ground to interfere”, despite “threats to a globally unique biodiversity hotspot” and Indigenous tribes at risk of displacement by the project, wrote Frontline.

- FISH FALLING: A new study found that fish biomass is “falling by 7.2% from as little as 0.1C of warming per decade”, noted the Guardian. While experts also pointed to the role of overfishing in marine life loss, marine ecologist and study lead author Dr Shahar Chaikin told the outlet: “Our research proves exactly what that biological cost [of warming] looks like underwater.”

- TOO HOT FOR COFFEE: According to new analysis by Climate Central, countries where coffee beans are grown “are becoming too hot to cultivate them”, reported the Guardian. The world’s top five coffee-growing countries faced “57 additional days of coffee-harming heat” annually because of climate change, it added.

Spotlight

Nature talks inch forward

This week, Carbon Brief covers the latest round of negotiations under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which occurred in Rome over 16-19 February.

The penultimate set of biodiversity negotiations before October’s Conference of the Parties ended in Rome last week, leaving plenty of unfinished business.

The CBD’s subsidiary body on implementation (SBI) met in the Italian capital for four days to discuss a range of issues, including biodiversity finance and reviewing progress towards the nature targets agreed under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

However, many of the major sticking points – particularly around finance – will have to wait until later this summer, leaving some observers worried about the capacity for delegates to get through a packed agenda at COP17.

The SBI, along with the subsidiary body on scientific, technical and technological advice (SBSTTA) will both meet in Nairobi, Kenya, later this summer for a final round of talks before COP17 kicks off in Yerevan, Armenia, on 19 October.

Money talks

Finance for nature has long been a sticking point at negotiations under the CBD.

Discussions on a new fund for biodiversity derailed biodiversity talks in Cali, Colombia, in autumn 2024, requiring resumed talks a few months later.

Despite this, finance was barely on the agenda at the SBI meetings in Rome. Delegates discussed three studies on the relationship between debt sustainability and implementation of nature plans, but the more substantive talks are set to take place at the next SBI meeting in Nairobi.

Several parties “highlighted concerns with the imbalance of work” on finance between these SBI talks and the next ones, reported Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

Lim Li Ching, senior researcher at Third World Network, noted that tensions around finance permeated every aspect of the talks. She told Carbon Brief:

“If you’re talking about the gender plan of action – if there’s little or no financial resources provided to actually put it into practice and implement it, then it’s [just] paper, right? Same with the reporting requirements and obligations.”

Monitoring and reporting

Closely linked to the issue of finance is the obligations of parties to report on their progress towards the goals and targets of the GBF.

Parties do so through the submission of national reports.

Several parties at the talks pointed to a lack of timely funding for driving delays in their reporting, according to ENB.

A note released by the CBD Secretariat in December said that no parties had submitted their national reports yet; by the time of the SBI meetings, only the EU had. It further noted that just 58 parties had submitted their national biodiversity plans, which were initially meant to be published by COP16, in October 2024.

Linda Krueger, director of biodiversity and infrastructure policy at the environmental not-for-profit Nature Conservancy, told Carbon Brief that despite the sparse submissions, parties are “very focused on the national report preparation”. She added:

“Everybody wants to be able to show that we’re on the path and that there still is a pathway to getting to 2030 that’s positive and largely in the right direction.”

Watch, read, listen

NET LOSS: Nigeria’s marine life is being “threatened” by “ghost gear” – nets and other fishing equipment discarded in the ocean – said Dialogue Earth.

COMEBACK CAUSALITY: A Vox long-read looked at whether Costa Rica’s “payments for ecosystem services” programme helped the country turn a corner on deforestation.

HOMEGROWN GOALS: A Straits Times podcast discussed whether import-dependent Singapore can afford to shelve its goal to produce 30% of its food locally by 2030.

‘RUSTING’ RIVERS: The Financial Times took a closer look at a “strange new force blighting the [Arctic] landscape”: rivers turning rust-orange due to global warming.

New science

- Lakes in the Congo Basin’s peatlands are releasing carbon that is thousands of years old | Nature Geoscience

- Natural non-forest ecosystems – such as grasslands and marshlands – were converted for agriculture at four times the rate of land with tree cover between 2005 and 2020 | Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- Around one-quarter of global tree-cover loss over 2001-22 was driven by cropland expansion, pastures and forest plantations for commodity production | Nature Food

In the diary

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean | Brasília

- 5 March: Nepal general elections

- 9-20 March: First part of the thirty-first session of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) | Kingston, Jamaica

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz.

Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits