中国的气候和能源政策呈现出一种悖论:在以惊人的速度发展清洁能源的同时,也未停下新建燃煤电厂的步伐。

仅在2023年,中国就新建了70吉瓦(GW)的煤电装机容量,比2019年增长了四倍,占当年全球新增煤电装机容量的95%。

煤电产能的激增引发了人们对中国二氧化碳(CO2)排放和气候目标能否实现,以及对未来出现搁浅资产风险的担忧。

由于光伏和风能发电量不稳定,中国政府将煤炭作为保障能源安全和满足快速增长的用电高峰的手段。

与此同时,中国的电力行业在成本、需求模式、监管和市场运作方面正在发生重大变化。我们的新研究表明,用于证明新煤炭产能合理性的传统经济计算方式可能已经过时。

我们使用一个简单的分析指标来评估能满足用电高峰需求的最经济方式是什么。结果表明,光伏加电池储能的组合可能是比新建煤电更具成本效益的选择。

中国电力格局发生了怎样的变化?

在过去十年里,可再生能源和电池储能的成本大幅下降,高峰时段的住宅和商业用电需求激增,电力交易市场获得了更大的吸引力。

与此同时,中国还宣布了“双碳”目标,即在2030年前实现碳达峰、2060年前实现碳中和。鉴于这些转型,建设更多未减排的煤电厂与中国的长期气候承诺相冲突,而且对满足用电需求对增长来说,可能不再是最具成本效益的选择。它还占用了清洁能源系统转型急需的资金。

替代指标如何评估成本?

我们的研究引入了一种替代指标,用于计算在满足不断增长的高峰用电需求的情况下,所需的最优成本投资。

这一指标,即“净容量成本”(net capacity cost),是满足用电高峰需求所需的基础设施投资的年化固定成本,减去该设施带给电力市场的收入,或其“系统价值”(system value)。 在该指标中,负数意味着这些投资将带来利润,而非支出。

为了探索在中国使用的情境,我们使用了一个简单的例子:在一个假定省份,高峰用电需求增加了1500兆瓦(MW)、全年需求增加了6570吉瓦时(GWh)。

然后,我们概述了满足高峰和全年能源需求的五种策略(情况),其涵盖了从严重依赖煤电到光伏和电池储能相结合的方式。

在不同的案例中,资源衡量的规模基于它们能够可靠地满足高峰供应需求和年度能源需求的程度。

- 情况1:新的煤炭发电能力可满足高峰和年度能源需求的所有增长。

- 情况2:光伏可满足70%的年度能源需求增长,煤炭可满足30%的年度能源需求增长;光伏可满足525兆瓦的高峰供应需求(由于光伏发电可能不在高峰期间,因此基于“容量可信度”进行折减),而煤电可提供剩余的975兆瓦。

- 情况3:光伏可满足所有年度能源需求增长;光伏和煤炭均可满足750兆瓦的高峰供应需求,同样通过容量可信度对光伏发电量进行折减。

- 情况4:光伏满足所有年度能源需求增长;光伏和电池均为高峰供电需求提供750兆瓦;电池提供调频储备(用于管理精确至分钟的供需差异的备用电源)。

- 情况5:光伏满足所有年度能源需求增长;广泛和电池均为高峰供电需求提供750兆瓦;电池提供能源套利(在价格或成本较低时充电,在价格或成本较高时放电)。

如下图所示,我们针对每种情况都计算了单个资源(煤、电池或光伏),以及整个系统每年获得1千瓦(kW)发电容量的年净成本,单位为人民币元。

表上半部分的资源净容量成本是指该资源的净成本(即年化固定成本减去该资源从提供能源和辅助服务,如调频,所获得的年收入)。正数表示电网运营商在增加或获取该资源时的净成本。

表下半部分的系统总净容量成本,是在每种情况下利用资源组合满足高峰需求增长的净成本。

我们用于计算系统净成本的权重是基于装机容量与高峰需求增长的比率。

不同能源组合满足用电需求的成本

| 情况 1 | 情况 2 | 情况 3 | 情况 4 | 情况 5 | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 资源净容量成本 (元/千瓦/年, 每千瓦装机容量) | |||||

| 煤炭 | 424 | 424 | 512 | ||

| 电池 | 248 | 781 | |||

| 光伏 | -128 | -128 | -128 | -128 | |

| 系统净容量成本 (元/千瓦/年, 每千瓦满足高峰用电需求且折减容量可信度后) | |||||

| 煤炭 | 471 | 306 | 236 | ||

| 电池 | 138 | 434 | |||

| 光伏 | -223 | -319 | -319 | -319 | |

| 总计 | 471 | 83 | -83 | -181 | 115 |

为了对这一简单分析进行压力测试,我们研究了不同来源的各种价格的敏感性。

由于中国的光伏价格已经很低,我们的敏感性分析主要集中在煤炭、电池和其他分析所需投入的价格上。

满足高峰用电需求最经济的方法是什么?

我们的结果表明,当电池储能提供调频储备时(情况4),光伏和储能的组合是满足高峰用电需求增长最具成本效益的选择。

在这种组合下,每获得1千瓦发电装机容量,电网运营商的成本为-181元(约-25美元或-20英镑)。

相比之下,新建煤电产能以满足高峰用电需求增长(情况1)是最昂贵的方案,每获得1千瓦装机容量的净容量成本为471元(约合65美元或52英镑)。

情况3,即大型煤电厂仅用作备用电源(几乎不发电),在中国可能出于政治原因而至少在短期内不可行。

另外两种情况(情况2和情况5)更具可比性,但鉴于自本分析报告发布以来,电池价格下降了30%以上,约为每瓦时(Wh)1元人民币(约合0.14美元或0.11英镑),因此情况5中的电池可能比情况2中的煤炭更具经济吸引力。

我们的解决方案如何助力中国实现气候目标?

我们的分析表明,为了应对不断变化的形势,在满足中国日益增长的能源需求的同时,实现其气候目标的近期战略是将电池储能纳入电力市场。

目前,中国政府允许包括电池在内的“新型储能”参与电力市场。然而,详细规定尚不明确,电池的参与可以更简单。

例如,电池储能不被允许提供“运转储备”,即为应对意外的供需误差所预留的发电量。如果允许电池储能提供运转储备,将增强其商业价值。

允许电池储能更多地参与市场将促进电池储能系统的持续创新和降低成本,同时为系统运营商提供宝贵的运营经验。

这种策略将与市场效益相符,并反映美国和欧洲近期的电力市场经验。

这也将有助于解决近期的产能和能源需求,因为电池和光伏发电通常比燃煤电厂的建设速度更快。

此外,它还有助于缓解未来新增燃煤发电与可再生能源之间的冲突。主要作为可再生能源发电备用电源的新建燃煤电厂要么很少运营,要么侵占了其他现有煤炭发电厂的运营时间和净收入,从而产生新搁浅资产的风险。

通过继续进行电力市场改革,也将促进对可再生能源发电和电力储存进行更有效的投资。

允许市场制定批发市场电价、允许可再生能源发电和电力储存参与批发市场,这可以提高其收入和利润。

此外,改革还将鼓励高效利用储能,这是我们的关键发现。储能可以为电力系统提供多种功能;批发电价有助于引导储能运营以最低的成本实现具有最高价值的功能。

中国国家能源局最近发出指令,要求将新型储能设施(非抽水蓄能)纳入电网调度运行,这是向我们概述的改革迈出的一步。

可能需要进一步确定适当的补偿机制,例如在某些省份对此类储能设施提供的所有服务进行容量补偿,以促进这些储能设施的可持续发展和并网。

最后,仅靠增加供应不太可能成为满足中国电力需求增长的最低成本方式。提高终端使用效率和“需求响应”也有助于降低供电的总体成本。

随着中国电力市场改革的不断深入,连接多个省份的区域市场设计,以及鼓励省份间资源共享的区域资源充裕性规划,也有助于以最具成本效益和最低碳的方式满足中国不断增长的用电量和高峰需求。

The post 嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠” appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

After Hurricane Katrina, a New Orleans Architect Turned to the Dutch to Learn to Live With Water

Before the storm, the city tried to engineer water out of sight. But, David Waggonner says, “you can’t live with water if you can’t see water.”

For years, David Waggonner designed courthouses and other public buildings at his architectural practice, Waggonner & Ball, in New Orleans. Then Hurricane Katrina struck in 2005, and Waggonner became convinced that New Orleans was getting something fundamentally wrong about its approach to flooding and water.

After Hurricane Katrina, a New Orleans Architect Turned to the Dutch to Learn to Live With Water

Climate Change

Hydrogen emissions are ‘supercharging’ the warming impact of methane

The warming impact of hydrogen has been “overlooked” in projections of climate change, according to authors of the latest “global hydrogen budget”.

The study, published in Nature, is the most comprehensive analysis yet of the global hydrogen cycle, showing how the gas moves between the atmosphere, land and ocean.

Hydrogen has long been recognised as a clean alternative to fossil fuels and an important component of the green energy transition.

However, while hydrogen is not itself a greenhouse gas, rising emissions are “supercharging” the warming effect of methane, the authors say.

Increasing levels of atmospheric hydrogen have led to “indirect” warming of 0.02C over the past decade, the study finds.

The authors say that limiting leaks from future hydrogen fuel projects and rapidly cutting methane emissions will be key to securing benefits from hydrogen as a clean-burning alternative to oil and gas.

The international team of scientists behind the study also produce the annual “global carbon budget”, which saw its 20th edition published last month.

‘Supercharging’ methane

Hydrogen is the lightest and most abundant element in the universe. It is also an explosive gas that contains more energy per unit of weight than fossil fuels.

The gas has long been recognised as a clean alternative to fossil fuels, because it only emits water when burned.

There are many ways to produce hydrogen. It is typically generated in a carbon-intensive process that relies on fossil fuels. However, renewable energy can be used to produce “green hydrogen” with near-zero carbon emissions.

Hydrogen “indirectly” heats the atmosphere through its interactions with other gases. This warming is mainly due to interplay between hydrogen and methane – a potent greenhouse gas that is the second biggest contributor to human-caused global warming after CO2.

This interplay involves molecules in the atmosphere called hydroxyl radicals. These naturally occurring molecules are known as the atmosphere’s “detergents” because they react with certain greenhouse gases, such as methane, converting them into other compounds that do not warm the planet.

Prof Rob Jackson is a scientist at Stanford University and an author on the study. He explains that hydrogen also reacts with hydroxyl radicals, effectively “using up” these detergents and leaving less to react with methane.

This effectively “extends the lifetime” of methane in the atmosphere, Jackson tells Carbon Brief, leading to higher concentrations and greater warming.

There is also a reciprocal effect, where more methane in the atmosphere leads to more hydrogen. This occurs because methane reacts with oxygen in the atmosphere in a process called “oxidation”, which produces hydrogen.

Jackson tells Carbon Brief that interactions between hydrogen and methane have “not really been considered in climate circles”, adding:

“I think people don’t realise that the dominant source of hydrogen in the world today is methane in the atmosphere.”

Overall, the study estimates that increasing levels of hydrogen in the atmosphere led to global warming of 0.02C over 2010-20. This climate impact has been “overlooked”, the researchers say in a press release.

Jackson tells Carbon Brief that although this level of warming “looks fairly small”, it is still “comparable” to the warming caused by emissions of individual countries, such as France.

The hydrogen cycle

The global hydrogen budget brings together a range of observed data and models to quantify sources of hydrogen emissions as well as “sinks”, which absorb the gas from the atmosphere.

The authors find that hydrogen levels in the atmosphere increased from 523 parts per billion (ppb) in 1992 to 543ppb in 2020.

The graphic below shows the main sources (up arrows) and sinks (down arrows) of hydrogen over 2010-20.

As the figure shows, the largest single contributor to rising hydrogen emissions over 2010-20 is from the oxidation of human-produced methane. Methane emissions are on the rise due to human activity, such as from the fossil fuel industry, livestock and waste.

According to the study, 56% of atmospheric hydrogen over 2010-20 was caused by the oxidation of methane and non-methane volatile organic compounds (NMVOCs) reacting with oxygen to produce hydrogen.

(NMVOCs are chemicals that are released naturally from vegetation and more rapidly during wildfires. Human-produced emissions of NMVOCs – for example, from oil refineries or car tailpipes – are also on the rise, according to the study.)

The study also points to leakage from industrial hydrogen production as another driver of rising atmospheric hydrogen levels.

Jackson tells Carbon Brief that hydrogen leakage is on the rise “not because manufacturing is getting dirtier, but because we’re making more hydrogen from coal and natural gas”.

Hydrogen can also be produced as an unintentional byproduct from the combustion of fossil fuels. The study finds that these emissions of hydrogen are decreasing.

At the same time, natural sources of hydrogen emissions have not shown any increasing or decreasing trend over time, the authors say.

One of the largest natural sources of hydrogen is through “nitrogen fixing” – a chemical process in which nitrogen is converted into ammonia, which releases hydrogen as a byproduct. This process locks down nitrogen into the soil and ocean, where it is used by plants and algae to grow.

Meanwhile, hydrogen sinks have “increased in response to rising atmospheric hydrogen” over the past three decades, the study says.

Nearly three-quarters of the global hydrogen sink comes from hydrogen getting trapped in soil – for example, by microbes taking in hydrogen to use for energy, or hydrogen seeping into the soil through diffusion.

Dr Zutao Ouyang is an assistant professor at the University of Harvard and lead author on the study. He tells Carbon Brief that soil uptake is “the main mechanism removing hydrogen from the atmosphere”, but adds that it also has “the greatest uncertainty” because there is “not much long-term data” on this component of the hydrogen budget.

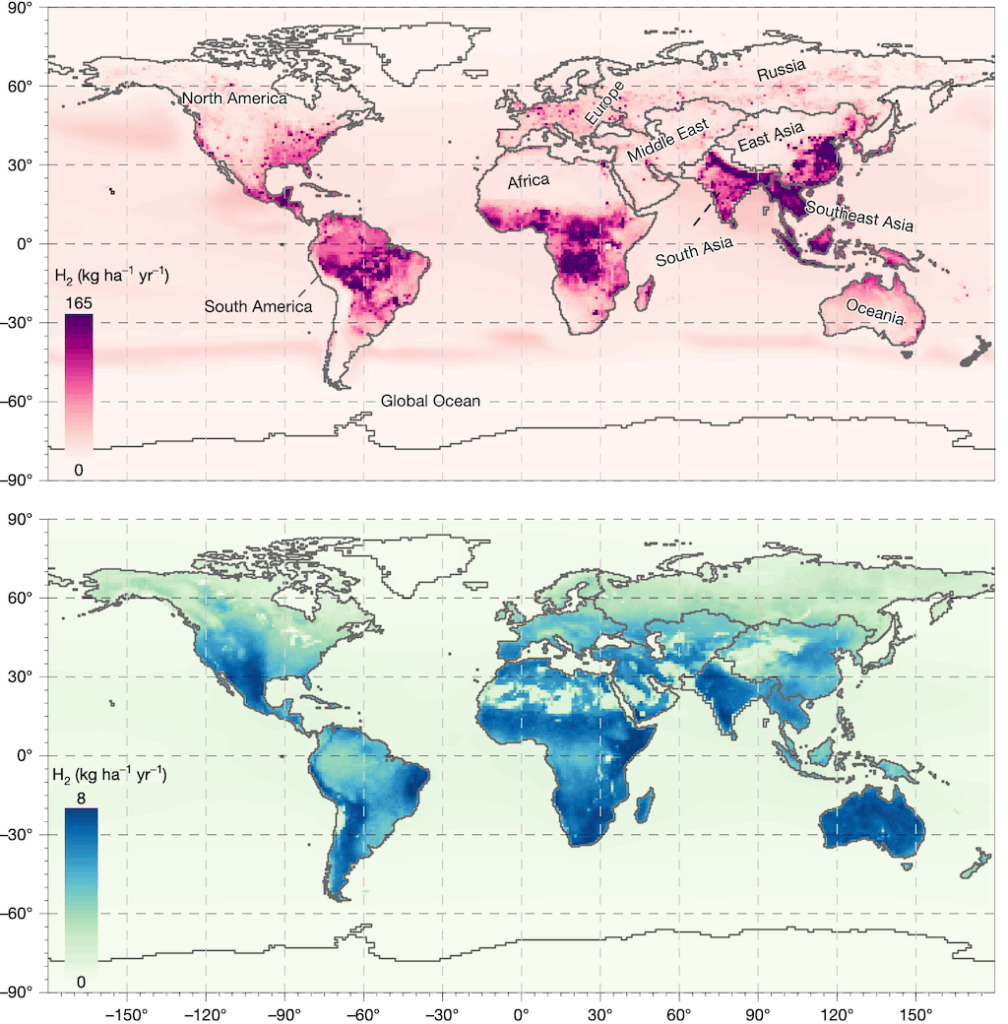

Mapped

Drawing on data including observational measurements and emissions inventories, the authors map the sources and sinks of hydrogen and their relative strength.

The maps below show the sources (top) and sinks (bottom) over 1990-2020, where darker colours indicate a stronger source or sink.

The largest “hotspots” for hydrogen emissions are in “south-east and east Asia”, according to the research. More widely, it says that “tropical regions” contribute about 60% of total hydrogen emissions.

The authors explain that these “hotspots” occur because the oxidation of methane and NMVOCs – processes that happen in the atmosphere and produce hydrogen as a byproduct – happen more quickly at higher temperatures.

They also find that these regions have more vegetation, which leads to higher NMVOC emissions.

For emissions related to human activity, east Asia and North America “contributed the most hydrogen emissions from fossil fuel combustion”, the study says, due to the “intensive fossil fuel use”.

Hydrogen emissions due to nitrogen fixation – when plants draw down nitrogen and release hydrogen as a byproduct – are highest in South America. The report links these emissions to the region’s “extensive cultivation” of crops such as soybeans and peanuts.

Dr Maria Sand is a senior researcher at CICERO and was not involved in the study. She tells Carbon Brief that the paper “provides a valuable and much-needed assessment of the global hydrogen budget”. She adds:

“By better constraining the sources and sinks of hydrogen, this study helps reduce the uncertainty in the climate impact [of hydrogen].”

Dr Nicola Warwick is a researcher at the National Centre for Atmospheric Science and assistant research professor at the University of Cambridge. She tells Carbon Brief that the study “provides an important update to our understanding of the atmospheric hydrogen budget by better constraining the key sources and sinks of hydrogen”.

She adds that better understanding of hydrogen uptake by soil – including how it responds to “climate-driven changes in soil moisture and temperature” – are “essential for reliably assessing the climate impacts of any future changes in hydrogen emissions”.

Study author Jackson tells Carbon Brief that he hopes the study will “prompt people to evaluate some of these emissions and sources and sinks in new ways and new places”.

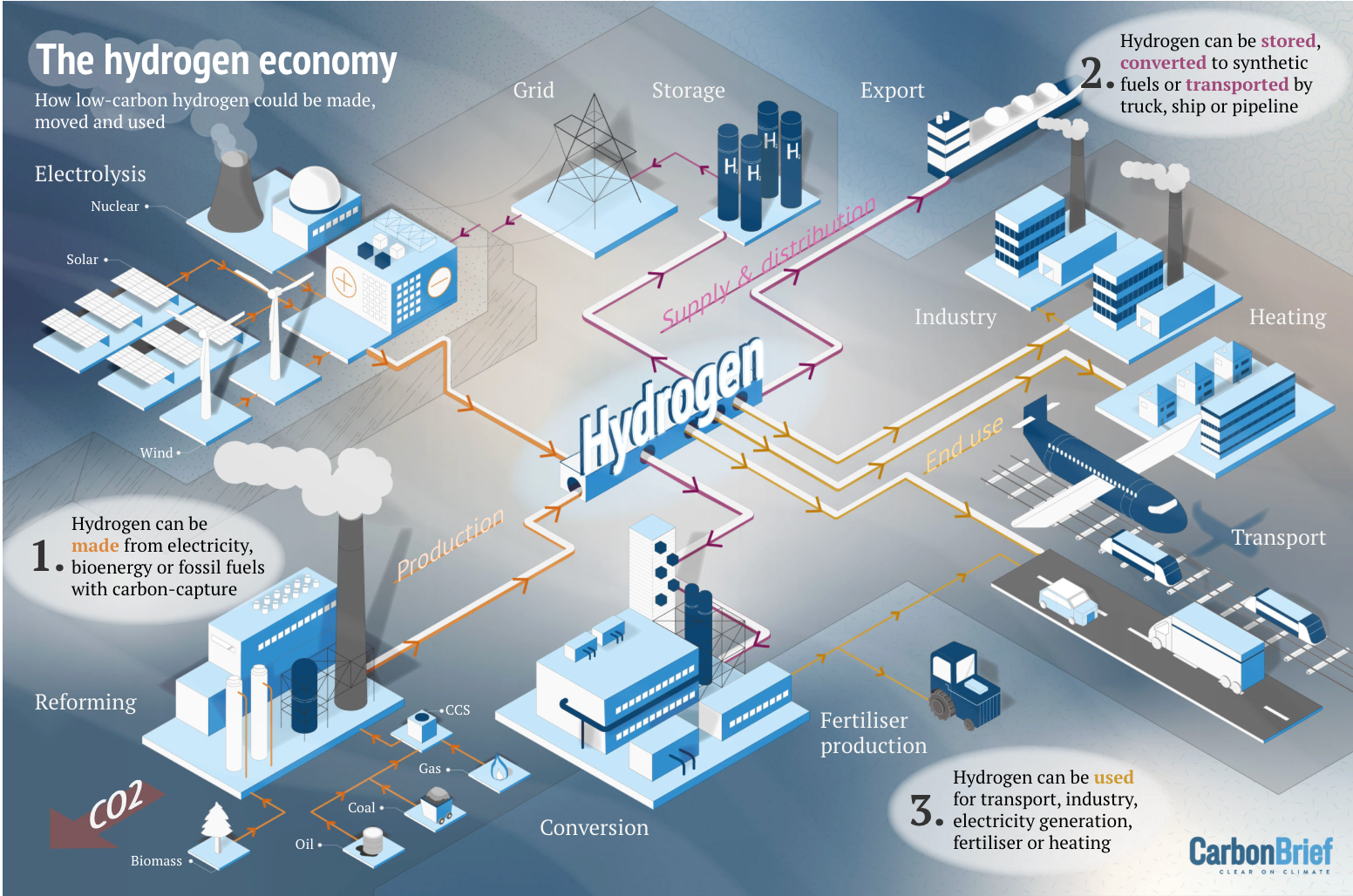

Hydrogen economy

In the pursuit of net-zero, hydrogen may play an increasingly important role in the global energy system.

There are many ways to produce hydrogen gas. Most hydrogen is currently generated through a process called steam reforming, which brings together fossil gas and steam to produce hydrogen, with CO2 as a by-product.

According to the study, more than 90% of hydrogen produced today uses this “carbon-intensive” method.

However, electricity can be used to split water into hydrogen and oxygen atoms, in a process called electrolysis. If renewable energy is used, hydrogen can be produced and consumed with near-zero carbon emissions.

Hydrogen can be stored, liquified and transported via pipelines, trucks or ships. It can be used to make fertiliser, fuel vehicles, heat homes, generate electricity or drive heavy industry.

This potential hydrogen “economy” is shown in the graphic below. The illustrations, with numbered captions from one to three, show how hydrogen could be made, moved and used

The graphic below, from Carbon Brief’s explainer, illustrates the elements of a potential hydrogen economy.

Jackson tells Carbon Brief that, in his opinion, hydrogen is a “brilliant” choice to replace fossil fuels on-site, for industries such as steel manufacturing. However, he says he is “concerned” about “a hydrogen economy that distributes hydrogen around the world in millions of users”, because there is potential for lots of the gas to leak.

He adds:

“We know that methane leakage is bad. Hydrogen is a smaller molecule than methane. So wherever you have methane and hydrogen together, if methane leaks, hydrogen is likely to leak even more.”

The authors model hydrogen emissions under a range of future warming scenarios over the coming century.

They find that in “low-warming scenarios with high hydrogen usage”, methane emissions are low, limiting the formation of hydrogen via the oxidation of methane. In this instance, changes in atmospheric hydrogen levels depend strongly on leakage.

Meanwhile, in higher-warming scenarios, the authors find that hydrogen use is “relatively low”, but methane emissions remain “largely unmitigated”. In this instance, they find that the additional hydrogen formed through the oxidation of methane can outweigh hydrogen released through leaks.

Overall, the authors suggest that hydrogen could cause additional warming of 0.01-0.05C by the year 2100. Study author Zutao tells Carbon Brief that this additional warming was not included in the climate projections in the last assessment report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The post Hydrogen emissions are ‘supercharging’ the warming impact of methane appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Hydrogen emissions are ‘supercharging’ the warming impact of methane

Climate Change

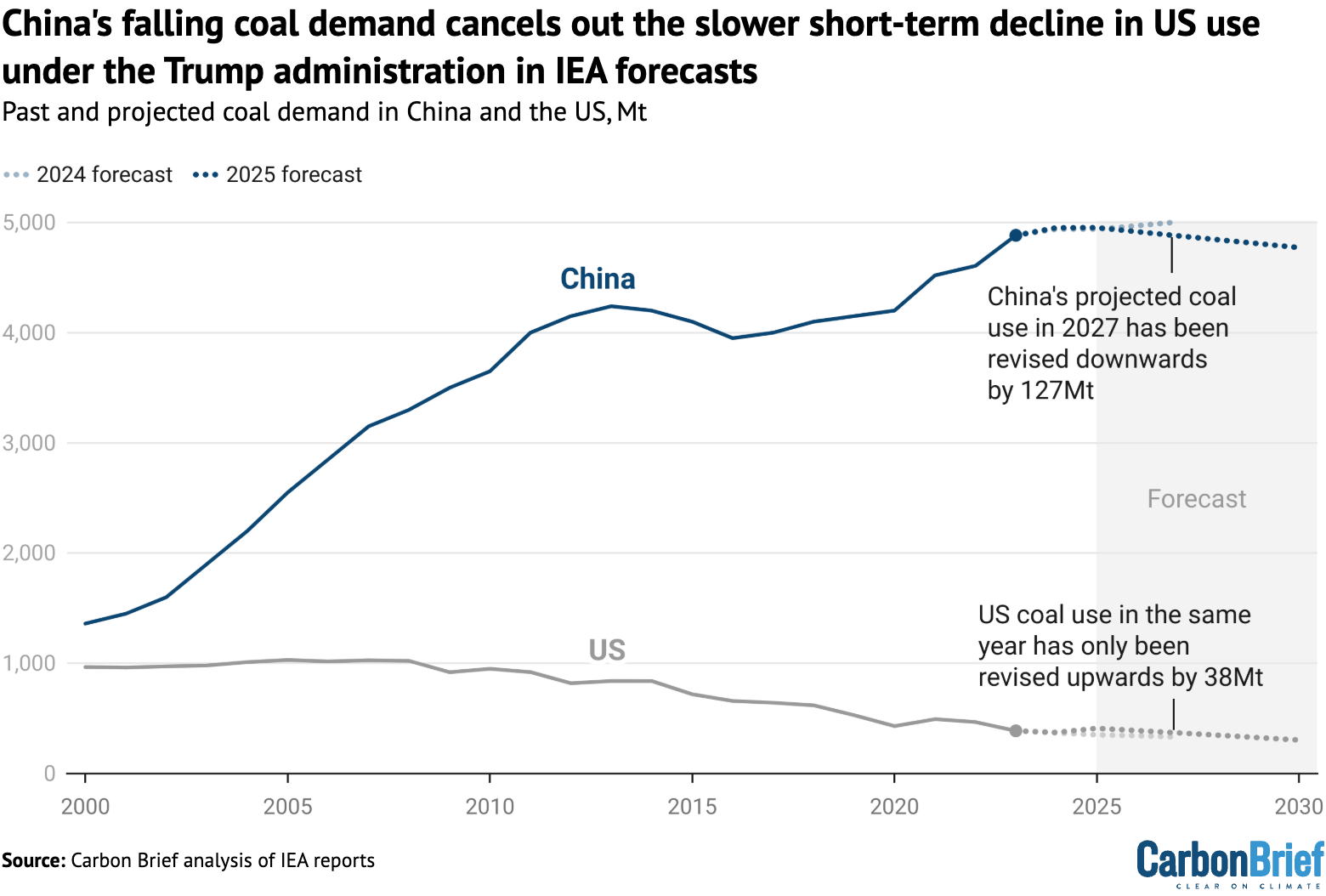

IEA: Declining coal demand in China set to outweigh Trump’s pro-coal policies

China’s coal demand is set to drop by 2027, more than cancelling out the effects of the Trump administration’s coal-friendly policies in the US, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

Global coal demand is due to grow by 0.5% year-on-year to reach record levels in 2025, according to the latest figures in the IEA’s annual market report.

Yet this will be reversed over the next couple of years, as a faster-than-expected expansion of renewables in key Asian nations and “structural declines” in Europe push coal demand down, the agency says.

While US coal demand is set to continue falling, the decline will be slower than expected last year, due to new federal government efforts to support the fuel.

However, the IEA’s upward revision of an extra 38m tonnes (Mt) of US coal use in 2027 is dwarfed by an even larger 126Mt downward revision in China’s coal use.

‘Unusual trends’

Coal demand will reach 8,845Mt around the world in 2025. This is slightly (44Mt) higher than the IEA had forecast in its 2024 coal market report.

The agency notes some “unusual regional trends” impacting this growth, including a 37Mt year-on-year increase in US coal demand in 2025 to 516Mt. This is 59Mt (17%) higher than the IEA projected in 2024.

A new suite of measures under the Trump administration have supported the short-term use of coal, including the modernisation of existing coal plants and reopening shuttered ones.

EU coal use declined at a slower pace than expected due to lower wind and hydropower output, according to the IEA. Nevertheless, the bloc “continues its structural decline” in coal demand, driven by renewables expansion, carbon pricing and coal phaseout pledges.

India saw an unexpected dip in coal consumption in 2025, linked to a strong monsoon season that increased hydropower output and curbed electricity demand.

In China, which accounts for more than half of the world’s coal use, coal demand remained roughly unchanged between 2024 and 2025, the IEA says.

Demand drop

In its 2024 market report, the IEA projected a continued increase in global coal demand out to 2027. This was largely driven by China, which was on track to see its demand exceed 5,000Mt each year, up from 4939Mt in 2024.

In its latest forecast, the agency estimates that global coal demand will instead “plateau” in the coming years, “falling slightly by the end of the decade”.

Again, this is largely due to trends in China’s power sector, reflecting the “crowding-out” of coal from the grid by the nation’s “formidable renewables expansion” and “steady growth” of nuclear power.

(By contrast, last year clean-power sources were only expected to meet “most of” China’s rising electricity demand.)

The IEA estimates that China’s coal demand will drop to 4,879Mt by 2027 and continue falling to 4,772Mt by the end of the decade.

The global projection for 2027 is 149Mt (2%) lower than expected last year.

As the chart below shows, while US short-term coal demand is now expected to be higher than the IEA’s previous forecast, the drop in China more than makes up for this.

The projected dip in Chinese coal use is largely attributed to the “rapid expansion” of its renewable-energy capacity, the IEA notes. Renewables are soon set to provide a greater share of China’s electricity than coal, rising to 49% of generation by 2030, according to the report.

The Chinese government has set an ambition of peaking coal use before 2030.

While the IEA’s data suggests this goal will be met, the agency stresses that several factors “could turn the slight drop into a small increase”.

These include higher electricity demand, an increase in coal-to-chemicals projects and fluctuations in renewable-energy output due to weather conditions and other factors.

Meanwhile, India remains a “key driver of global coal demand”, but the new report also downgrades estimates for the nation’s future coal growth. The IEA forecasts that Indian coal demand will be 1,383Mt in 2027 – 39Mt (3%) lower than last year’s forecast.

This comes as a growing share of India’s electricity mix is provided by low-carbon power sources, with coal’s share set to decline from 70% in 2025 to 60% by 2030, according to the IEA.

The post IEA: Declining coal demand in China set to outweigh Trump’s pro-coal policies appeared first on Carbon Brief.

IEA: Declining coal demand in China set to outweigh Trump’s pro-coal policies

-

Climate Change4 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases4 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Why airlines are perfect targets for anti-greenwashing legal action

-

Renewable Energy5 months ago

US Grid Strain, Possible Allete Sale