A new Greenpeace International report, Toxic Skies: How Agribusiness is Choking the Amazon, reveals how fires linked to industrial agriculture are turning the forest’s air toxic during the dry season. The findings are a stark warning that the Amazon’s crisis is not only about trees. It is about the air millions of people breathe, and the health of our shared planet.

When the sun rises over Porto Velho, on the edge of the Brazilian Amazon, it does not pierce through the mist. It struggles through the smoke. For months each year, the air fills with the haze of fires deliberately set to clear forests for cattle or to renew pasturelands. What was once the world’s greenest ecosystem often breathes air contaminated with higher levels of toxic particles than Beijing, São Paulo or Santiago, according to the report.

What the study found

Researchers monitored air quality in two Amazonian cities, Porto Velho (Rondônia) and Lábrea (Amazonas), combining satellite and ground-based data. The results are alarming:

- During the record-breaking fire season of 2024, levels of fine particulate matter (PM2.5) exceeded WHO daily health guidelines by more than 20 times.

- Even in 2025, a year with far fewer fires, the air still exceeded the guidelines by over six times.

- Between 2019 and 2024, the annual average pollution in Porto Velho was higher than in major global megacities, largely driven by sharp increases in PM2.5 levels during the fire season.

- Around 75% of burned areas around Porto Velho in 2024 are used as pasture for cattle production, showing that most fires are linked to grazing land use.

- More than half of the total burned area in 2024 in the Amazon biome falls within a 360km radius around the facilities of Brazil’s largest meatpacker, JBS. Meatpackers such as JBS do not effectively prohibit and monitor the deliberate use of fire in their supply chains – leaving meatpackers exposed to the risk of indirect or direct supply chain links, including through maintaining business relations, with farms in burned areas.

This is not a natural disaster. It is a business model that profits from destruction and public suffering.

Breathing in the crisis

The Amazon’s fires are not acts of nature. They are deliberately lit to clear forest or renew pastures for cattle. And, behind every statistic are human stories. Hilda Barabadá Karitiana, from the Karitiana Indigenous Territory near Porto Velho, describes how her community lives with the smoke:

During the dry season, the air becomes thick with smoke. Even when the fire is far away, we feel it. Sore throats, constant coughing, and irritated eyes. It affects everyone.– Hilda Barabadá Karitiana

For people like Hilda, the smoke is not just a seasonal nuisance. It is a public health emergency. Exposure to high levels of PM2.5 causes respiratory infections, heart disease and asthma, especially among children and older adults. The air itself has become an agent of crisis.

Debunking Myths

✘ Fires in the Amazon region occur naturally and are beneficial for the ecosystem.

Fires in the Amazon region are caused by human activity and are highly destructive to the rainforest ecosystem.

Fires in the Amazon region are caused by human activity and are highly destructive to the rainforest ecosystem.

✘ Fires in the Amazon happen because of logging.

Vast areas of the Amazon biome are set on fire to make way for cattle ranching.

Vast areas of the Amazon biome are set on fire to make way for cattle ranching.

A turning point before COP30

This year’s COP30, hosted in Belém, on the edge of the Amazon, will be the first UN Climate Summit held inside a tropical forest. It is an opportunity to put Amazonian voices and air quality at the centre of global climate negotiations and to demand that governments and corporations act.

Chief Zé Bajaga, from the Caititu Indigenous Territory, says:

Here in the Amazon, we face invasion, fires and pollution from companies that profit while our land burns. Those who destroy for money must be held accountable.– Chief Zé Bajaga

What needs to happen now

World leaders need to step up and:

- COP30 should deliver an action plan to implement the UNFCCC’s 2030 target to halt and reverse deforestation and forest degradation of the world’s forests. It’s time to turn commitments into action.

- Governments must urgently regulate the agricultural and financial sectors to ensure their alignment with the Paris Agreement, the Global Biodiversity Framework, and the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

- Governments must ensure the transition to truly ecological and just food systems, an end to deforestation, and the reduction of emissions associated with agriculture, including methane.

- World leaders must ensure funding for real solutions to protect and restore forests by providing finance directly accessible to Indigenous Peoples and Local Communities.

The Amazon’s toxic skies are not inevitable. They are the product of political choices and economic greed. As world leaders prepare for COP30, this is the moment to act.

Lis Cunha is a campaigner with Greenpeace International’s Respect the Amazon campaign.

Toxic Skies: The Amazon is now breathing dirtier air than the world’s biggest cities

Climate Change

Battery passport plan aims to clean up the industry powering clean energy

For millions of consumers, the sustainability scheme stickers found on everything from bananas to chocolate bars and wooden furniture are a way to choose products that are greener and more ethical than some of the alternatives.

Inga Petersen, executive director of the Global Battery Alliance (GBA), is on a mission to create a similar scheme for one of the building blocks of the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy systems: batteries.

“Right now, it’s a race to the bottom for whoever makes the cheapest battery,” Petersen told Climate Home News in an interview.

The GBA is working with industry, international organisations, NGOs and governments to establish a sustainable and transparent battery value chain by 2030.

“One of the things we’re trying to do is to create a marketplace where products can compete on elements other than price,” Petersen said.

Under the GBA’s plan, digital product passports and traceability would be used to issue product-level sustainability certifications, similar to those commonplace in other sectors such as forestry, Petersen said.

Managing battery boom’s risks

Over the past decade, battery deployment has increased 20-fold, driven by record-breaking electric vehicle (EV) sales and a booming market for batteries to store intermittent renewable energy.

Falling prices have been instrumental to the rapid expansion of the battery market. But the breakneck pace of growth has exposed the potential environmental and social harms associated with unregulated battery production.

From South America to Zimbabwe and Indonesia, mineral extraction and refining has led to social conflict, environmental damage, human rights violations and deforestation. In Indonesia, the nickel industry is powered by coal while in Europe, production plants have been met with strong local opposition over pollution concerns.

“We cannot manage these risks if we don’t have transparency,” Petersen said.

The GBA was established in 2017 in response to concerns about the battery industry’s impact as demand was forecast to boom and reports of child labour in the cobalt mines of the Democratic Republic of the Congo made headlines.

The alliance’s initial 19 members recognised that the industry needed to scale rapidly but with “social, environmental and governance guardrails”, said Petersen, who previously worked with the UN Environment Programme to develop guiding principles to minimise the environmental impact of mining.

Digital battery passport

Today, the alliance is working to develop a global certification scheme that will recognise batteries that meet minimum thresholds across a set of environmental, social and governance benchmarks it has defined along the entire value chain.

Participating mines, manufacturing plants and recycling facilities will have to provide data for their greenhouse gas emissions as well as how they perform against benchmarks for assessing biodiversity loss, pollution, child and forced labour, community impacts and respect for the rights of Indigenous peoples, for example.

The data will be independently verified, scored, aggregated and recorded on a battery passport – a digital record of the battery’s composition, which will include the origin of its raw materials and its performance against the GBA’s sustainability benchmarks.

The scheme is due to launch in 2027.

A carrot and a stick

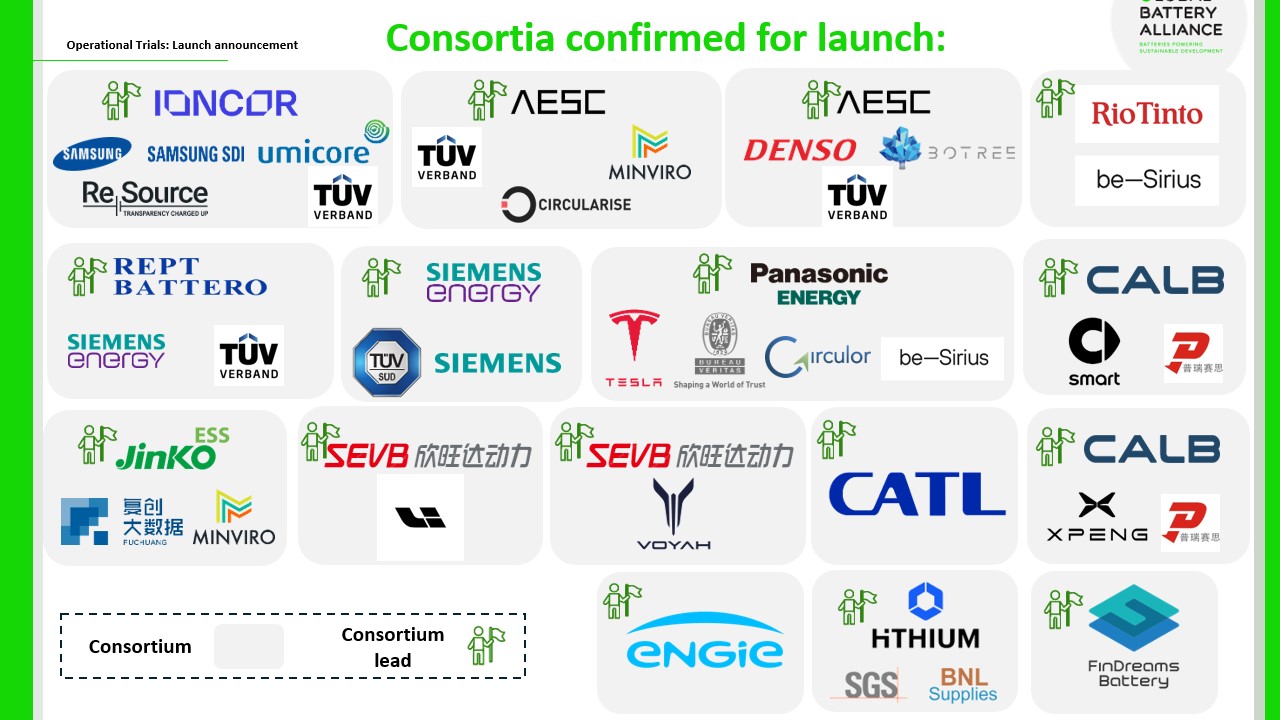

Since the start of the year, some of the world’s largest battery companies have been voluntarily participating in the biggest pilot of the scheme to date.

More than 30 companies across the EV battery and stationary storage supply chains are involved, among them Chinese battery giants CATL and BYD subsidiary FinDreams Battery, miner Rio Tinto, battery producers Samsung SDI and Siemens, automotive supplier Denso and Tesla.

Petersen said she was “thrilled” about support for the scheme. Amid a growing pushback against sustainability rules and standards, “these companies are stepping up to send a public signal that they are still committed to a sustainable and responsible battery value chain,” she said.

There are other motivations for battery producers to know where components in their batteries have come from and whether they have been produced responsibly.

In 2023, the EU adopted a law regulating the batteries sold on its market.

From 2027, it mandates all batteries to meet environmental and safety criteria and to have a digital passport accessed via a QR code that contains information about the battery’s composition, its carbon footprint and its recycling content.

The GBA certification is not intended as a compliance instrument for the EU law but it will “add a carrot” by recognising manufacturers that go beyond meeting the bloc’s rules on nature and human rights, Petersen said.

Raising standards in complex supply chain

But challenges remain, in part due to the complexity of battery supply chains.

In the case of timber, “you have a single input material but then you have a very complex range of end products. For batteries, it’s almost the reverse,” Petersen said.

The GBA wants its certification scheme to cover all critical minerals present in batteries, covering dozens of different mining, processing and manufacturing processes and hundreds of facilities.

“One of the biggest impacts will be rewarding the leading performers through preferential access to capital, for example, with investors choosing companies that are managing their risk responsibly and transparently,” Petersen said.

It could help influence public procurement and how companies, such as EV makers, choose their suppliers, she added. End consumers will also be able to access a summary of the GBA’s scores when deciding which product to buy.

US, Europe rush to build battery supply chain

Today, the GBA has more than 150 members across the battery value chain, including more than 50 companies, of which over a dozen are Chinese firms.

China produces over three-quarters of batteries sold globally and it dominates the world’s battery recycling capacity, leaving the US and Europe scrambling to reduce their dependence on Beijing by building their own battery supply chains.

Petersen hopes the alliance’s work can help build trust in the sector amid heightened geopolitical tensions. “People want to know where the materials are coming from and which actors are involved,” she said.

At the same time, companies increasingly recognise that failing to manage sustainability risks can threaten their operations. Protests over environmental concerns have shut down mines and battery factories across the world.

“Most companies know that and that’s why they’re making these efforts,” Petersen added.

The post Battery passport plan aims to clean up the industry powering clean energy appeared first on Climate Home News.

Battery passport plan aims to clean up the industry powering clean energy

Climate Change

Reheating plastic food containers: what science says about microplastics and chemicals in ready meals

How often do you eat takeaway food? What about pre-prepared ready meals? Or maybe just microwaving some leftovers you had in the fridge? In any of these cases, there’s a pretty good chance the container was made out of plastic. Considering that they can be an extremely affordable option, are there any potential downsides we need to be aware of? We decided to investigate.

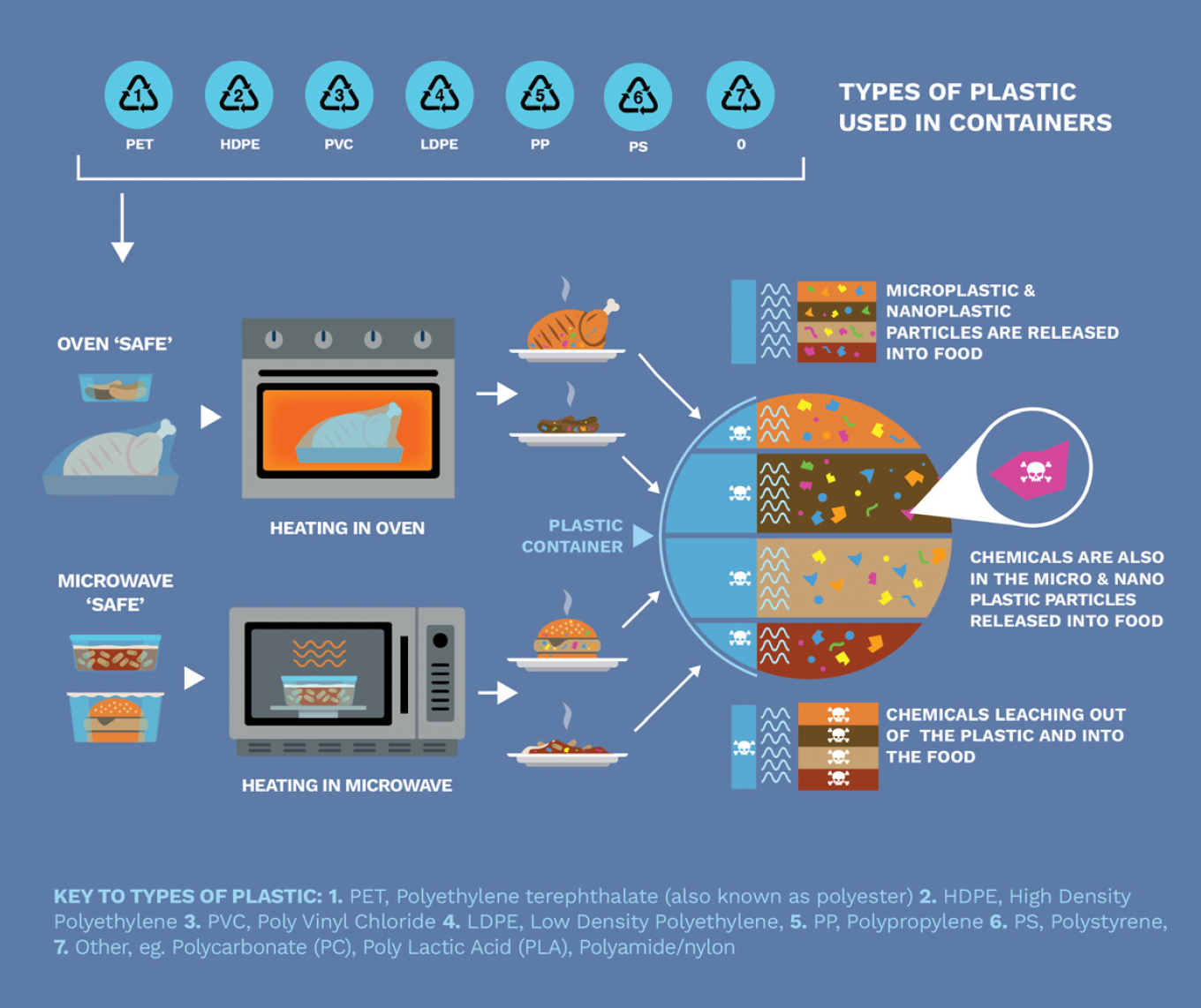

Scientific research increasingly shows that heating food in plastic packaging can release microplastics and plastic chemicals into the food we eat. A new Greenpeace International review of peer-reviewed studies finds that microwaving plastic food containers significantly increases this release, raising concerns about long-term human health impacts. This article summarises what the science says, what remains uncertain, and what needs to change.

There’s no shortage of research showing how microplastics and nanoplastics have made their way throughout the environment, from snowy mountaintops and Arctic ice, into the beetles, slugs, snails and earthworms at the bottom of the food chain. It’s a similar story with humans, with microplastics found in blood, placenta, lungs, liver and plenty of other places. On top of this, there’s some 16,000 chemicals known to be either present or used in plastic, with a bit over a quarter of those chemicals already identified as being of concern. And there are already just under 1,400 chemicals that have been found in people.

Not just food packaging, but plenty of household items either contain or are made from plastic, meaning they potentially could be a source of exposure as well. So if microplastics and chemicals are everywhere (including inside us), how are they getting there? Should we be concerned that a lot of our food is packaged in plastic?

Greenpeace analysis of 24 articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals found that the plastics we use to package our food are directly risking our health.

Heating food in plastic packaging dramatically increases the levels of microplastics and chemicals that leach into our food.

Plastic food packaging: the good, the bad, and the ugly

The growing trend towards ready meals, online shopping and restaurant delivery, and away from home-prepared meals and individual grocery shopping, is happening in every region of the world. Since the first microwaveable TV dinners were introduced in the US in the 1950s to sell off excess stock of turkey meat after Thanksgiving holidays, pre-packaged ready meals have grown hugely in sales. The global market is worth $190bn in 2025, and is expected to reach a total volume of 71.5 million tonnes by 2030. It’s also predicted that the top five global markets for convenience food (China, USA, Japan, Mexico and Russia) will remain relatively unchanged up to 2030, with the most revenue in 2019 generated by the North America region.

A new report from Greenpeace International set out to analyse articles in peer-reviewed, scientific journals to look at what exactly the research has to say about plastic food packaging and food contact plastics.

Here’s what we found.

Our review of 24 recent articles highlights a consistent picture that regulators, businesses and

consumers should be concerned about: when food is packaged in plastic and then microwaved, this significantly increases the risk of both microplastic and chemical release, and that these microplastics and chemicals will leach into the food inside the packaging.

And not just some, but a lot of microplastics and chemicals.

When polystyrene and polypropylene containers filled with water were microwaved after being stored in the fridge or freezer, one study found they released anywhere between 100,000-260,000 microplastic particles, and another found that five minutes of microwave heating could release between 326,000-534,000 particles into food.

Similarly there are a wide range of chemicals that can be and are released when plastic is heated. Across different plastic types, there are estimated to be around 16,000 different chemicals that can either be used or present in plastics, and of these around 4,200 are identified as being hazardous, whilst many others lack any form of identification (hazardous or otherwise) at all.

The research also showed that 1,396 food contact plastic chemicals have been found in humans, several of which are known to be hazardous to human health. At the same time, there are many chemicals for which no research into the long-term effects on human health exists.

Ultimately, we are left with evidence pointing towards increased release of microplastics and plastic chemicals into food from heating, the regular migration of microplastics and chemicals into food, and concerns around what long-term impacts these substances have on human health, which range from uncertain to identified harm.

The known unknowns of plastic chemicals and microplastics

The problem here (aside from the fact that plastic chemicals are routinely migrating into our food), is that often we don’t have any clear research or information on what long-term impacts these chemicals have on human health. This is true of both the chemicals deliberately used in plastic production (some of which are absolutely toxic, like antimony which is used to make PET plastic), as well as in what’s called non-intentionally added substances (NIAS).

NIAS refers to chemicals which have been found in plastic, and typically originate as impurities, reaction by-products, or can even form later when meals are heated. One study found that a UV stabiliser plastic additive reacted with potato starch when microwaved to create a previously unknown chemical compound.

We’ve been here before: lessons from tobacco, asbestos and lead

Although none of this sounds particularly great, this is not without precedence. Between what we do and don’t know, waiting for perfect evidence is costly both economically and in terms of human health. With tobacco, asbestos, and lead, a similar story to what we’re seeing now has played out before. After initial evidence suggesting problems and toxicity, lobbyists from these industries pushed back to sow doubt about the scientific validity of the findings, delaying meaningful action. And all the while, between 1950-2000, tobacco alone led to the deaths of around 60 million people. Whilst distinguishing between correlation and causation, and finding proper evidence is certainly important, it’s also important to take preventative action early, rather than wait for more people to be hurt in order to definitively prove the point.

Where to from here?

This is where adopting the precautionary principle comes in. This means shifting the burden of proof away from consumers and everyone else to prove that a product is definitely harmful (e.g. it’s definitely this particular plastic that caused this particular problem), and onto the manufacturer to prove that their product is definitely safe. This is not a new idea, and plenty of examples of this exist already, such as the EU’s REACH regulation, which is centred around the idea of “no data, no market” – manufacturers are obligated to provide data demonstrating the safety of their product in order to be sold.

Greenpeace analysis of 24 articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals found that the plastics we use to package our food are directly risking our health.

Heating food in plastic packaging dramatically increases the levels of microplastics and chemicals that leach into our food.

But as it stands currently, the precautionary principle isn’t applied to plastics. For REACH in particular, plastics are assessed on a risk-based approach, which means that, as the plastic industry itself has pointed out, something can be identified as being extremely hazardous, but is still allowed to be used in production if the leached chemical stays below “safe” levels, despite that for some chemicals a “safe” low dose is either undefined, unknown, or doesn’t exist.

A better path forward

Governments aren’t acting fast enough to reduce our exposure and protect our health. There’s no shortage of things we can do to improve this situation. The most critical one is to make and consume less plastic. This is a global problem that requires a strong Global Plastics Treaty that reduces global plastic production by at least 75% by 2040 and eliminates harmful plastics and chemicals. And it’s time that corporations take this growing threat to their customers’ health seriously, starting with their food packaging and food contact products. Here are a number of specific actions policymakers and companies can take, and helpful hints for consumers.

Policymakers & companies

- Implement the precautionary principle:

- For policymakers – Stop the use of hazardous plastics and chemicals, on the basis of their intrinsic risk, rather than an assessment of “safe” levels of exposure.

- For companies – Commit to ensure that there is a “zero release” of microplastics and hazardous chemicals from packaging into food, alongside an Action Plan with milestones to achieve this by 2035

- Stop giving false assurances to consumers about “microwave safe” containers

- Stop the use of single-use and plastic packaging, and implement policies and incentives to foster the uptake of reuse systems and non-toxic packaging alternatives.

Consumers

- Encourage your local supermarkets and shops to shift away from plastic where possible

- Avoid using plastic containers when heating/reheating food

- Use non-plastic refill containers

Trying to dodge plastic can be exhausting. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, you’re not alone. We can only do so much in this broken plastic-obsessed system. Plastic producers and polluters need to be held accountable, and governments need to act faster to protect the health of people and the planet. We urgently need global governments to accelerate a justice-centred transition to a healthier, reuse-based, zero-waste future. Ensure your government doesn’t waste this once-in-a-generation opportunity to end the age of plastic.

Climate Change

REPORT: Are We Cooked?

The hidden health risks of plastic-packaged ready meals

Ready meals and takeaways promise convenience – hot food, fast. The labels on the plastic trays reassure us that they are ‘safe’ to heat in a microwave or oven. But are we exposed to potentially dangerous microplastics and chemical additives along with our food?

Greenpeace decided to check

Greenpeace International’s analysis of 24 research papers in peer-reviewed scientific journals found that the plastics we use to package our food are exposing us to health risks – and none more so than heated ready meals and takeaways. Specifically:

- Plastic containers can release microplastics and toxic chemicals into our food.

- Leaching into food dramatically increases when the food is heated in the plastic packaging.

Regulators and the industry are failing to act on the plastics problem, which is already causing a global waste crisis, yet the production of plastic is set to more than double by 2050 from current levels. The fossil fuel and petrochemical industry is banking on this for its future growth – and relying on the growing trend for plastic packaged ready meals.

Past experience shows that the costs to society multiply when action is delayed by the denial of convincing scientific evidence. This has led to health and environmental disasters, from tobacco, to asbestos, to hazardous chemicals. When it comes to plastics, we already know that their global health impacts are costing trillions, and have more than enough evidence to act.

- At least 1,396 plastic food contact chemicals have been found in human bodies, including several which are a known threat to human health, linked to conditions such as cancers, infertility, neurodevelopmental disorders, and cardiovascular and metabolic diseases like obesity and type 2 diabetes.

Current regulation is clearly insufficient to protect public health. We need to act now and apply the precautionary principle to the way that we package food and stop this uncontrolled chemistry experiment that nobody signed up for.

As negotiations on the UN Plastics Treaty advance, we cannot ignore the potential impacts on human health.

Key Findings:

- Microwaving plastic containers can release hundreds of thousands of micro- and nanoplastics in minutes. One study found 326,000 to 534,000 particles leaching into food simulants after just five minutes of microwave heating, up to seven times more than oven heating.

- Heating dramatically increases chemical contamination. Across multiple studies, every microwave test sample of common plastics such as polypropylene and polystyrene leached chemical additives into food or food simulants, including plasticisers and antioxidants.

- More than 4,200 hazardous chemicals are known to be used in or present in plastics, most are not regulated in food packaging. Some, like bisphenols, phthalates, PFAS “forever chemicals” and even toxic metals such as antimony, are linked to cancer, infertility, hormone disruption and metabolic disease.

- Plastic chemicals are already in our bodies. At least 1,396 plastic-related chemicals have been detected in human bodies, with growing evidence linking exposure to neurodevelopmental disorders, cardiovascular disease, obesity and type 2 diabetes.

- Old, scratched or reused containers are worse. Worn plastic releases nearly double the number of microplastic particles compared to new packaging.

Reducing reliance on plastic packaging is not just an environmental issue – it is a public health imperative. And a global one. That’s why we urgently need governments to agree on a strong and effective Global Plastics Treaty.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits