CCL volunteers on the Capitol steps for our annual group photo

Reflections from Capitol Hill: Climate advocacy and a moonshot mindset

By CCL volunteer Joel McKinnon

Each year, several hundred Citizens’ Climate Lobby volunteers travel to Washington, D.C., at their own expense to participate in CCL’s Summer Conference and Lobby Day, holding hundreds of meetings with legislators on Capitol Hill. This year, for the first time, I decided to join them. By the time it was over, I was left with a renewed sense of possibility—not only in what we can accomplish as climate advocates, but in how we connect as human beings in this critical work.

Joel McKinnon

Let’s start with the basics: I was there, suit and all. A rented one, to be exact. Somewhere between the personal awkwardness of being dressed like a businessman and the shoes that quickly turned into instruments of mild torture, I found myself reflecting on how odd and wonderful it is to do something so uncomfortable for something that matters so much. Climate work is rarely glamorous, but it does have moments of unexpected grace, and this event brought many.

Our meetings on the Hill were thoughtful, serious, and at times, deeply human. In Rep. Sam Liccardo’s office, there was a striking constellation of personal stories: a mother and daughter speaking with grace and clarity, a Spanish teacher reconnecting serendipitously with a former student who now serves on the congressional staff, and a husband and wife seasoned in CCL advocacy grounding the conversation with perspective and calm purpose. The discussion was energized, sincere, and open to meaningful dialogue.

The conversation with Rep. Jerry Panetta’s aide was similarly warm, frank, and collaborative. Our team was received with a sense of familiarity, a quiet nod to the long-term relationships we’ve built. The staffer’s stories of late-night phone calls during past legislative efforts, and her reflections on political realities, revealed the emotional labor behind policy work and the role we play as trusted outside partners.

But advocacy wasn’t the only kind of connection this trip offered.

I also carved out time for a different kind of fuel: reconnecting with people who’ve been part of my journey. I met up with my brother in Pittsburgh before the trip to watch my hometown team play baseball. I spent time with Tobias, a friend I’d met online and finally met in person in Philadelphia. And in D.C., I reunited with Darryl, an old bandmate and drummer, who took me on an inspiring side trip the Sunday before the conference.

We spent the afternoon at the Smithsonian National Air and Space Museum, where the Wright Brothers exhibit and the Race to the Moon wing stopped me in my tracks. One particular multimedia piece explored the cultural and political tensions of the 1960s — civil rights, war, economic disparity — all unfolding alongside an unprecedented effort of human collaboration and technical innovation that culminated in landing a person on the moon. It framed the moonshot not as a solitary feat, but as a symphony of effort from thousands of unsung contributors.

Standing there, I couldn’t help but draw the parallel to our climate crisis. The space race wasn’t just about rockets. It was about will, imagination, and urgency. It required us to act across divides, invent new technologies, and, most importantly, believe we could do something no one had done before.

That exhibit, quiet, moving, and brilliantly assembled, reminded me that the path ahead on climate isn’t hopeless. It’s just hard. But we as a people have done hard things, nearly impossible things, before.

So yes, I’ll remember the talking points. But I’ll also remember the aching shoes, the laughter with friends, the warmth of a chance hallway encounter, and that lingering feeling I had standing next to the Apollo capsule. We can do this if we have the will, the spirit, and the desire to put in the work it takes. This trip gave me a sense of what’s possible when all seems chaotic and confused. We are still a government of, by, and for the people. And we have to reach further than ever before to do the right thing for the future of the planet we live on.

Joel McKinnon is a volunteer in CCL’s San Mateo, California, chapter.

The post Reflections from Capitol Hill: Climate advocacy and a moonshot mindset appeared first on Citizens' Climate Lobby.

Reflections from Capitol Hill: Climate advocacy and a moonshot mindset

Greenhouse Gases

Analysis: Coal power drops in China and India for first time in 52 years after clean-energy records

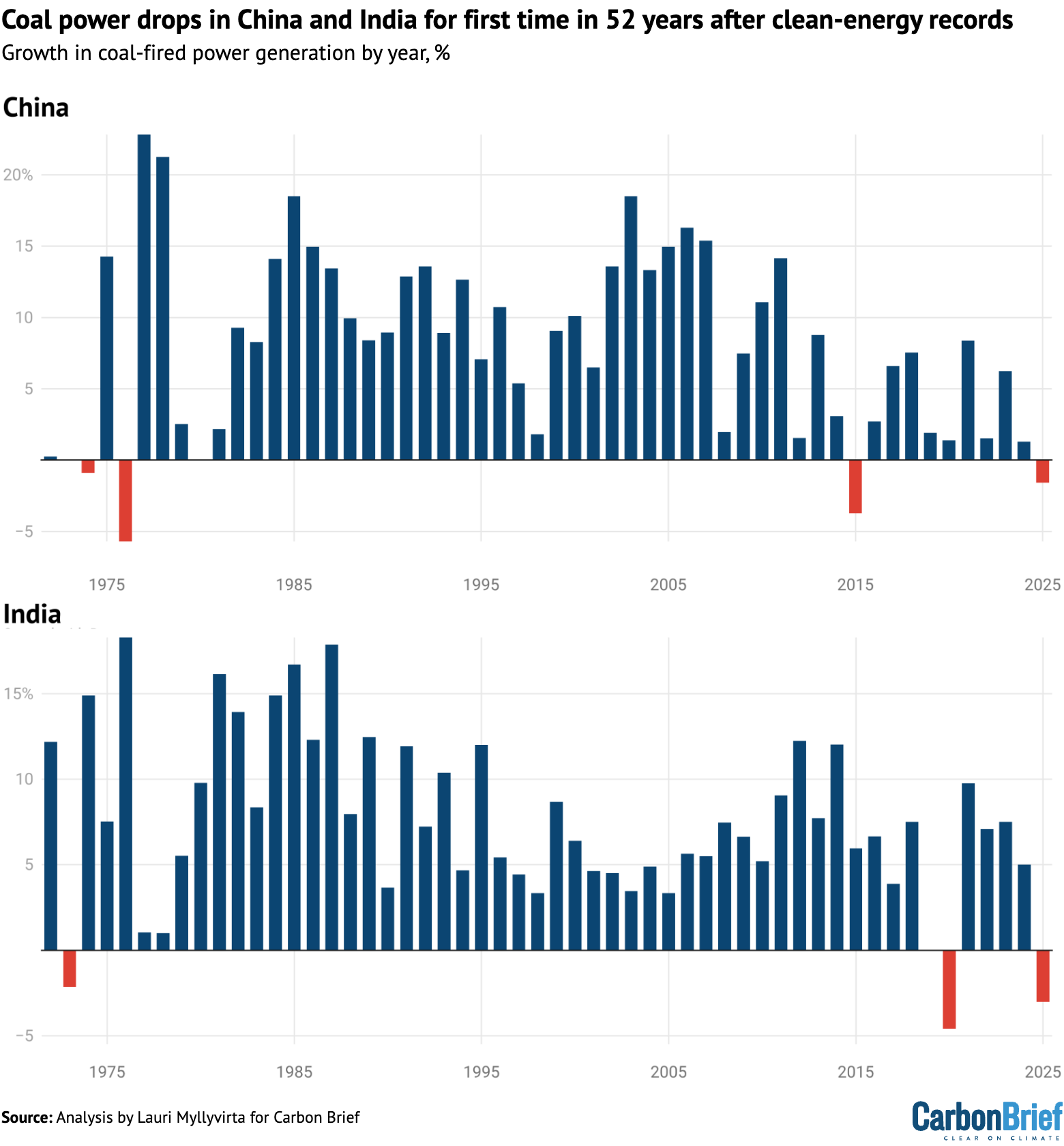

Coal power generation fell in both China and India in 2025, the first simultaneous drop in half a century, after each nation added record amounts of clean energy.

The new analysis for Carbon Brief shows that electricity generation from coal in India fell by 3.0% year-on-year (57 terawatt hours, TWh) and in China by 1.6% (58TWh).

The last time both countries registered a drop in coal power output was in 1973.

The fall in 2025 is a sign of things to come, as both countries added a record amount of new clean-power generation last year, which was more than sufficient to meet rising demand.

Both countries now have the preconditions in place for peaking coal-fired power, if China is able to sustain clean-energy growth and India meets its renewable energy targets.

These shifts have international implications, as the power sectors of these two countries drove 93% of the rise in global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions from 2015-2024.

While many challenges remain, the decline in their coal-power output marks a historic moment, which could help lead to a peak in global emissions.

Double drop

The new analysis shows that power generation from coal fell by 1.6% in China and by 3.0% in India in 2025, as non-fossil energy sources grew quickly enough in both countries to cover electricity consumption growth. This is illustrated in the figure below.

Growth in coal-fired power generation in China and India by year, %, 1972-2025. Source: Analysis by Lauri Myllyvirta for Carbon Brief. Further details below.

China achieved this feat even as electricity demand growth remained rapid at 5% year-on-year. In India, the drop in coal was due to record clean-energy growth combined with slower demand growth, resulting from mild weather and a longer-term slowdown.

The simultaneous drop for coal power in both countries in 2025 is the first since 1973, when much of the world was rocked by the oil crisis. Both China and India saw weak power demand growth that year, combined with increases in power generation from other sources – hydro and nuclear in the case of India and oil in the case of China.

China’s recent clean-energy generation growth, if sustained, is already sufficient to secure a peak in coal power. Similarly, India’s clean-energy targets, if they are met, will enable a peak in coal before 2030, even if electricity demand growth accelerates again.

In 2025, China will likely have added more than 300 gigawatts (GW) of solar and 100GW of wind power, both clear new records for China and, therefore, for any country ever.

Power generation from solar and wind increased by 450TWh in the first 11 months of the year and nuclear power delivering another 35TWh. This put the growth of non-fossil power generation, excluding hydropower, squarely above the 460TWh increase in demand.

Growth in clean-power generation has kept ahead of demand growth and, as a result, power-sector coal use and CO2 emissions have been falling since early 2024.

Coal use outside the power sector is falling, too, mostly driven by falling output of steel, cement and other construction materials, the largest coal-consuming sectors after power.

In India’s case, the fall in coal-fired power in 2025 was a result of accelerated clean-energy growth, a longer-term slowdown in power demand growth and milder weather, which resulted in a reduction in power demand for air conditioning.

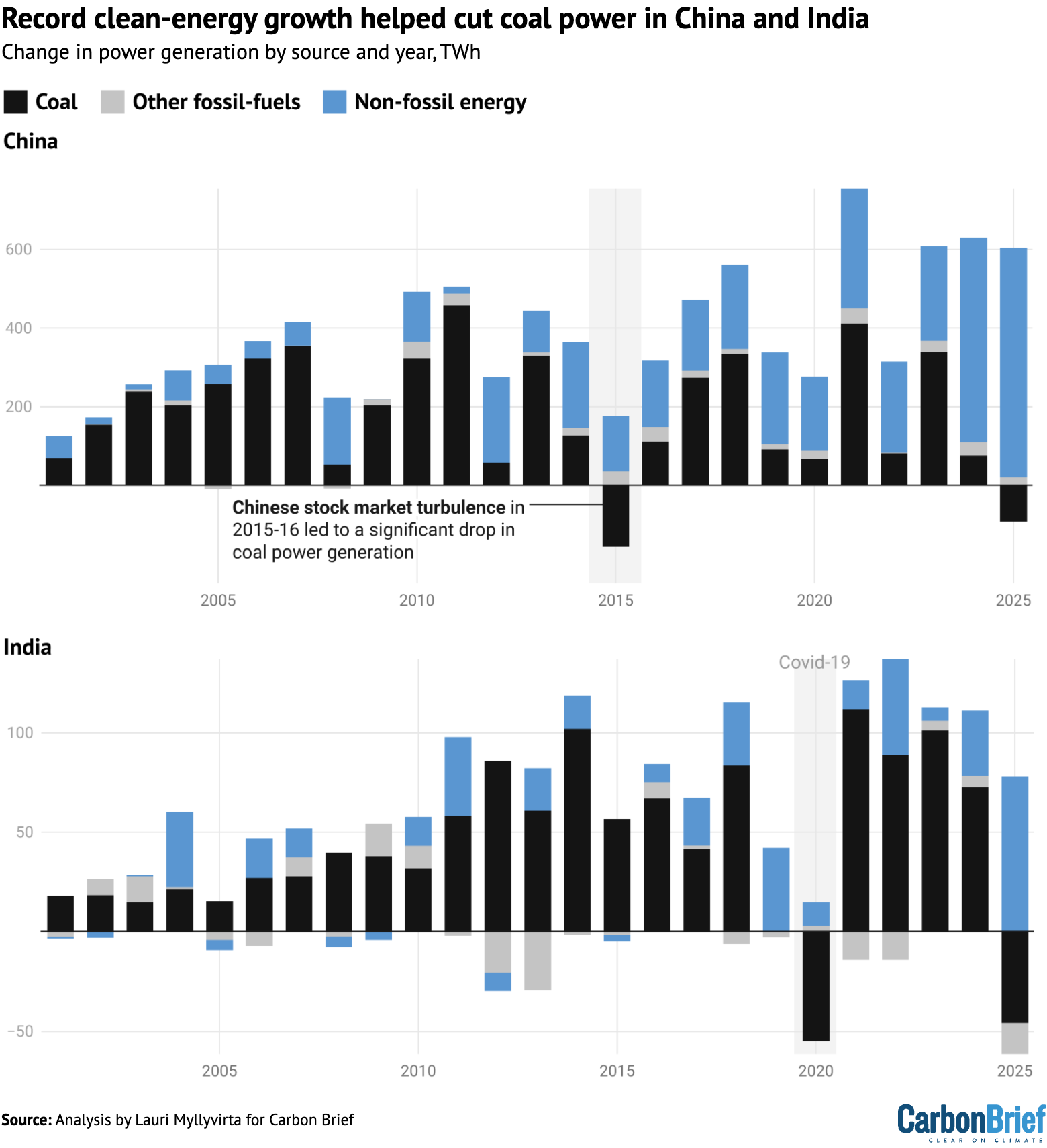

Faster clean-energy growth contributed 44% of the reduction in coal and gas, compared to the trend in 2019-24, while 36% was contributed by milder weather and 20% by slower underlying demand growth. This is the first time that clean-energy growth has played a significant role in driving down India’s coal-fired power generation, as shown below.

Change in power generation in China and India by source and year, terawatt hours 2000-2025. Source: Analysis by Lauri Myllyvirta for Carbon Brief. Further details below.

India added 35GW of solar, 6GW wind and 3.5GW hydropower in the first 11 months of 2025, with renewable energy capacity additions picking up 44% year-on-year.

Power generation from non-fossil sources grew 71TWh, led by solar at 33TWh, while total generation increased 21TWh, similarly pushing down power generation from coal and gas.

The increase in clean power is, however, below the average demand growth recorded from 2019 to 2024, at 85TWh per year, as well as below the projection for 2026-30.

This means that clean-energy growth would need to accelerate in order for coal power to see a structural peak and decline in output, rather than a short-term blip.

Meeting the government’s target for 500GW of non-fossil power capacity by 2030, set by India’s prime minister Narendra Modi in 2021, requires just such an acceleration.

Historic moment

While the accelerated clean-energy growth in China and India has upended the outlook for their coal use, locking in declines would depend on meeting a series of challenges.

First, the power grids would need to be operated much more flexibly to accommodate increasing renewable shares. This would mean updating old power market structures – built to serve coal-fired power plants – both in China and India.

Second, both countries have continued to add new coal-fired power capacity. In the short term, this is leading to a fall in capacity utilisation – the number of hours each coal unit is able to operate – as power generation from coal falls.

(Both China and India have been adding new coal-power capacity in response to increases in peak electricity demand. This includes rising demand for air conditioning, in part resulting from extreme heat driven by the historical emissions that have caused climate change.)

If under-construction and permitted coal-power projects are completed, they would increase coal-power capacity by 28% in China and 23% in India. Without marked growth in power generation from coal, the utilisation of this capacity would fall significantly, causing financial distress for generators and adding costs for power users.

In the longer term, new coal-power capacity additions would have to be slowed down substantially and retirements accelerated, to make space for further expansion of clean energy in the power system.

Despite these challenges ahead, the drop in coal power and record increase in clean energy in China and India marks a historic moment.

Power generation in these two countries drove more than 90% of the increase in global CO2 emissions from all sources between 2015-2024 – with 78% from China and 16% from India – making their power sectors the key to peaking global emissions.

About the data

China’s coal-fired power generation until November 2025 is calculated from monthly data on the capacity and utilisation of coal-fired power plants from China Electricity Council (CEC), accessed through Wind Financial Terminal.

For December, year-on-year growth is based on a weekly survey of power generation at China’s coal plants by CEC, with data up to 25 December. This data closely predicts CEC numbers for the full month.

Other power generation and capacity data is derived from CEC and National Bureau of Statistics data, following the methodology of CREA’s monthly snapshot of energy and emissions trends in China.

For India, the analysis uses daily power generation data and monthly capacity data from the Central Electricity Authority, accessed through a dashboard published by government thinktank Niti Aayog.

The role of coal-fired power in China and India in driving global CO2 emissions is calculated from the International Energy Agency (IEA) World Energy Balances until 2023, applying default CO2 emission factors from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

To extend the calculation to 2024, the year-on-year growth of coal-fired power generation in China and India is taken from the sources above, and the growth of global fossil-fuel CO2 emissions was taken from the Energy Institute’s Statistical Review of World Energy.

The time series of coal-fired power generation since 1971, used to establish the fact that the previous time there was a drop in both countries was 1973, was taken from the IEA World Energy Balances. This dataset uses fiscal years ending in March for India. Calendar-year data was available starting from 2000 from Ember’s yearly electricity data.

The post Analysis: Coal power drops in China and India for first time in 52 years after clean-energy records appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Coal power drops in China and India for first time in 52 years after clean-energy records

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 9 January 2026: US to exit global climate treaty; Venezuelan oil ‘uncertainty’; ‘Hardest truth’ for Africa’s energy transition

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

US to pull out from UNFCC, IPCC

CLIMATE RETREAT: The Trump administration announced its intention to withdraw the US from the world’s climate treaty, CNN reported. The move to leave the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), in addition to 65 other international organisations, was announced via a White House memorandum that states these bodies “no longer serve American interests”, the outlet added. The New York Times explained that the UNFCCC “counts all of the other nations of the world as members” and described the move as cementing “US isolation from the rest of the world when it comes to fighting climate change”.

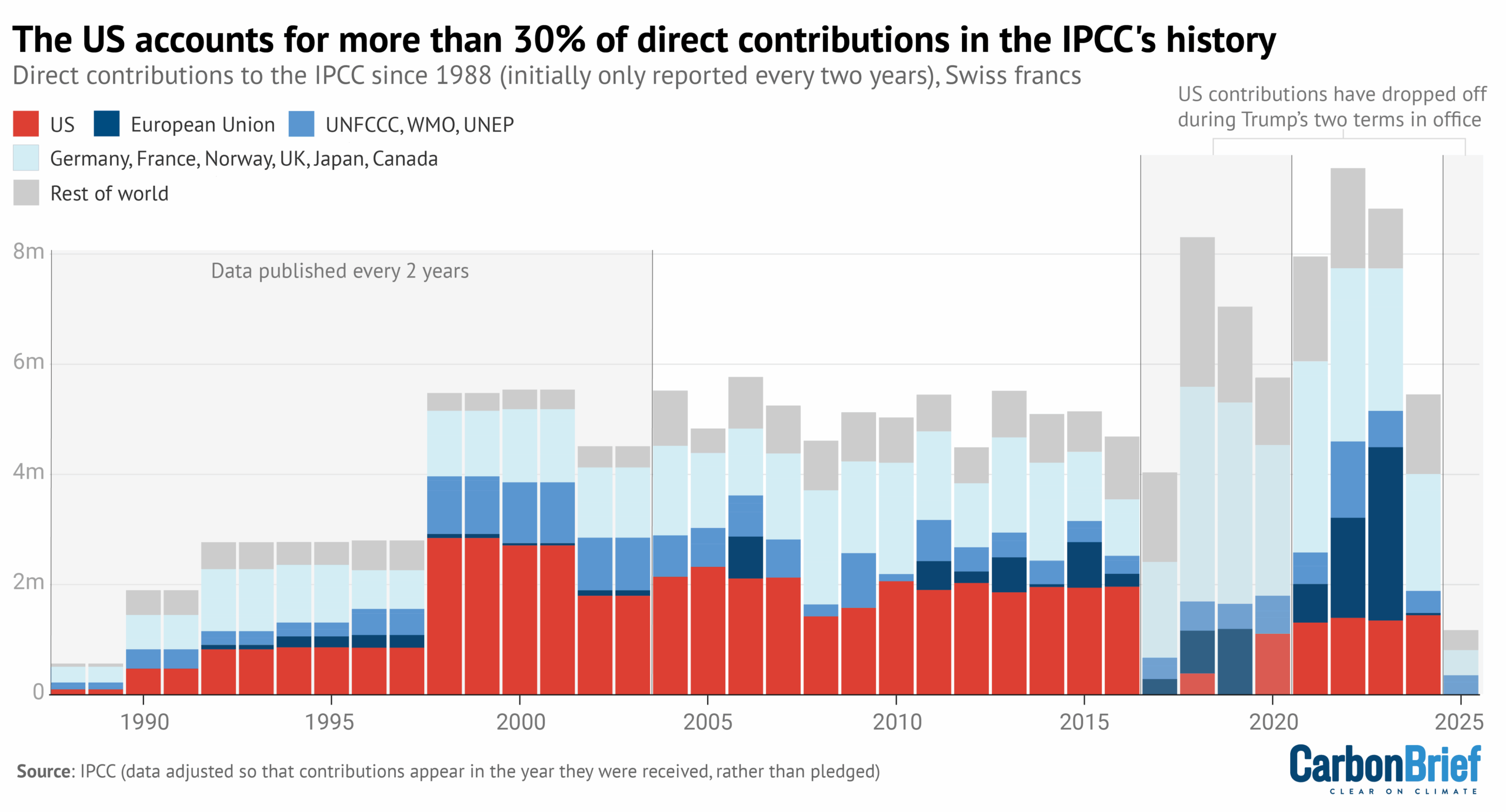

MAJOR IMPACT: The Associated Press listed all the organisations that the US is exiting, including other climate-related bodies such as the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) and the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA). The exit also means the withdrawal of US funding from these bodies, noted the Washington Post. Bloomberg said these climate actions are likely to “significantly limit the global influence of those entities”. Carbon Brief has just published an in-depth Q&A on what Trump’s move means for global climate action.

Oil prices fall after Venezuela operation

UNCERTAIN GLUT: Global oil prices fell slightly this week “after the US operation to seize Venezuelan president Nicolás Maduro created uncertainty over the future of the world’s largest crude reserves”, reported the Financial Times. The South American country produces less than 1% of global oil output, but it holds about 17% of the world’s proven crude reserves, giving it the potential to significantly increase global supply, the publication added.

TRUMP DEMANDS: Meanwhile, Trump said Venezuela “will be turning over” 30-50m barrels of oil to the US, which will be worth around $2.8bn (£2.1bn), reported BBC News. The broadcaster added that Trump claims this oil will be sold at market price and used to “benefit the people of Venezuela and the US”. The announcement “came with few details”, but “marked a significant step up for the US government as it seeks to extend its economic influence in Venezuela and beyond”, said Bloomberg.

Around the world

- MONSOON RAIN: At least 16 people have been killed in flash floods “triggered by torrential rain” in Indonesia, reported the Associated Press.

- BUSHFIRES: Much of Australia is engulfed in an extreme heatwave, said the Guardian. In Victoria, three people are missing amid “out of control” bushfires, reported Reuters.

- TAXING EMISSIONS: The EU’s landmark carbon border levy, known as “CBAM”, came into force on 1 January, despite “fierce opposition” from trading partners and European industry, according to the Financial Times.

- GREEN CONSUMPTION: China’s Ministry of Commerce and eight other government departments released an action plan to accelerate the country’s “green transition of consumption and support high-quality development”, reported Xinhua.

- ACTIVIST ARRESTED: Prominent Indian climate activist Harjeet Singh was arrested following a raid on his home, reported Newslaundry. Federal forces have accused Singh of “misusing foreign funds to influence government policies”, a suggestion that Singh rejected as “baseless, biased and misleading”, said the outlet.

- YOUR FEEDBACK: Please let us know what you thought of Carbon Brief’s coverage last year by completing our annual reader survey. Ten respondents will be chosen at random to receive a CB laptop sticker.

47%

The share of the UK’s electricity supplied by renewables in 2025, more than any other source, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Latest climate research

- Deforestation due to the mining of “energy transition minerals” is a “major, but overlooked source of emissions in global energy transition” | Nature Climate Change

- Up to three million people living in the Sudd wetland region of South Sudan are currently at risk of being exposed to flooding | Journal of Flood Risk Management

- In China, the emissions intensity of goods purchased online has dropped by one-third since 2000, while the emissions intensity of goods purchased in stores has tripled over that time | One Earth

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

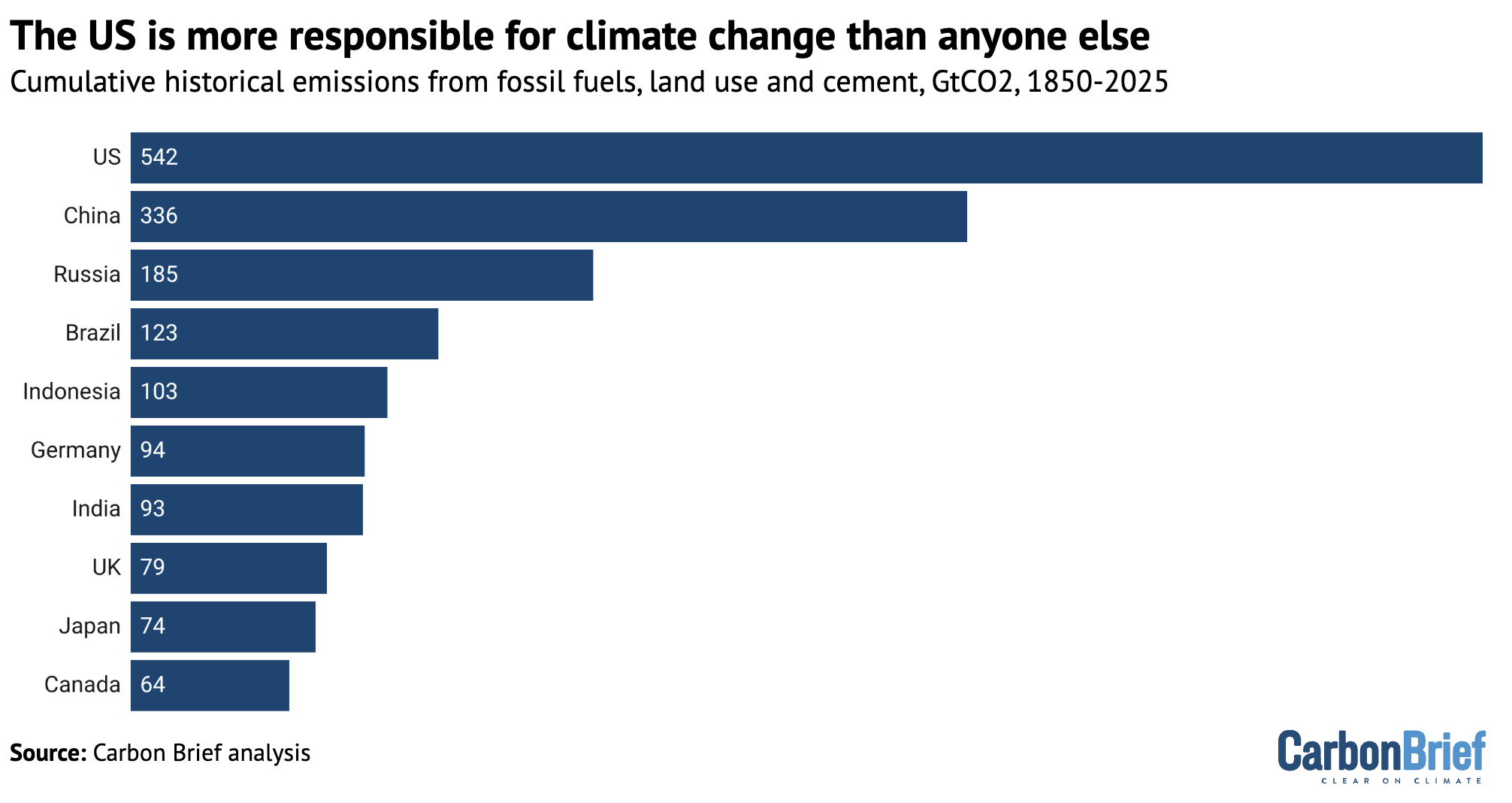

Captured

The US, which has announced plans to withdraw from the UNFCCC, is more responsible for climate change than any other country or group in history, according to Carbon Brief analysis. The chart above shows the cumulative historical emissions of countries since the advent of the industrial era in 1850.

Spotlight

How to think about Africa’s just energy transition

African nations are striving to boost their energy security, while also addressing climate change concerns such as flood risks and extreme heat.

This week, Carbon Brief speaks to the deputy Africa director of the Natural Resource Governance Institute, Ibrahima Aidara, on what a just energy transition means for the continent.

Carbon Brief: When African leaders talk about a “just energy transition”, what are they getting right? And what are they still avoiding?

Ibrahima Aidara: African leaders are right to insist that development and climate action must go together. Unlike high-income countries, Africa’s emissions are extremely low – less than 4% of global CO2 emissions – despite housing nearly 18% of the world’s population. Leaders are rightly emphasising universal energy access, industrialisation and job creation as non-negotiable elements of a just transition.

They are also correct to push back against a narrow narrative that treats Africa only as a supplier of raw materials for the global green economy. Initiatives such as the African Union’s Green Minerals Strategy show a growing recognition that value addition, regional integration and industrial policy must sit at the heart of the transition.

However, there are still important blind spots. First, the distributional impacts within countries are often avoided. Communities living near mines, power infrastructure or fossil-fuel assets frequently bear environmental and social costs without sharing in the benefits. For example, cobalt-producing communities in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, or lithium-affected communities in Zimbabwe and Ghana, still face displacement, inadequate compensation, pollution and weak consultation.

Second, governance gaps are sometimes downplayed. A just transition requires strong institutions (policies and regulatory), transparency and accountability. Without these, climate finance, mineral booms or energy investments risk reinforcing corruption and inequality.

Finally, leaders often avoid addressing the issue of who pays for the transition. Domestic budgets are already stretched, yet international climate finance – especially for adaptation, energy access and mineral governance – remains far below commitments. Justice cannot be achieved if African countries are asked to self-finance a global public good.

CB: Do African countries still have a legitimate case for developing new oil and gas projects, or has the energy transition fundamentally changed what ‘development’ looks like?

IA: The energy transition has fundamentally changed what development looks like and, with it, how African countries should approach oil and gas. On the one hand, more than 600 million Africans lack access to electricity and clean cooking remains out of reach for nearly one billion people. In countries such as Mozambique, Nigeria, Senegal and Tanzania, gas has been framed to expand power generation, reduce reliance on biomass and support industrial growth. For some contexts, limited and well-governed gas development can play a transitional role, particularly for domestic use.

On the other hand, the energy transition has dramatically altered the risks. Global demand uncertainty means new oil and gas projects risk becoming stranded assets. Financing is shrinking, with many development banks and private lenders exiting fossil fuels. Also, opportunity costs are rising; every dollar locked into long-lived fossil infrastructure is a dollar not invested in renewables, grids, storage or clean industry.

Crucially, development today is no longer just about exporting fuels. It is about building resilient, diversified economies. Countries such as Morocco and Kenya show that renewable energy, green industry and regional power trade can support growth without deepening fossil dependence.

So, the question is no longer whether African countries can develop new oil and gas projects, but whether doing so supports long-term development, domestic energy access and fiscal stability in a transitioning world – or whether it risks locking countries into an extractive model that benefits few and exposes countries to future shocks.

CB: What is the hardest truth about Africa’s energy transition that policymakers and international partners are still unwilling to confront?

IA: For me, the hardest truth is this: Africa cannot deliver a just energy transition on unfair global terms. Despite all the rhetoric, global rules still limit Africa’s policy space. Trade and investment agreements restrict local content, industrial policy and value-addition strategies. Climate finance remains fragmented and insufficient. And mineral supply chains are governed largely by consumer-country priorities, not producer-country development needs.

Another uncomfortable truth is that not every “green” investment is automatically just. Without strong safeguards, renewable energy projects and mineral extraction can repeat the same harms as fossil fuels: displacement, exclusion and environmental damage.

Finally, there is a reluctance to admit that speed alone is not success. A rushed transition that ignores governance, equity and institutions will fail politically and socially, and, ultimately, undermine climate goals.

If Africa’s transition is to succeed, international partners must accept African leadership, African priorities and African definitions of development, even when that challenges existing power dynamics in global energy and mineral markets.

Watch, read, listen

CRISIS INFLAMED: In the Brazilian newspaper Folha de São Paulo, columnist Marcelo Leite looked into the climate impact of extracting more oil from Venezuela.

BEYOND TALK: Two Harvard scholars argued in Climate Home News for COP presidencies to focus less on climate policy and more on global politics.

EU LEVIES: A video explainer from the Hindu unpacked what the EU’s carbon border tax means for India and global trade.

Coming up

- 10-12 January: 16th session of the IRENA Assembly, Abu Dhabi

- 13-15 January: Energy Security and Green Infrastructure Week, London

- 13-15 January: The World Future Energy Summit, Abu Dhabi

- 15 January: Uganda general elections

Pick of the jobs

- WRI Polsky Energy Center, global director | Salary: around £185,000. Location: Washington DC; the Hague, Netherlands; New Delhi, Mumbai, or Bengaluru, India; or London

- UK government Advanced Research and Invention Agency, strategic communications director – future proofing our climate and weather | Salary: £115,000. Location: London

- The Wildlife Trusts, head of climate and international policy | Salary: £50,000. Location: London

- Children’s Investment Fund Foundation, senior manager for climate | Salary: Unknown. Location: London, UK

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 9 January 2026: US to exit global climate treaty; Venezuelan oil ‘uncertainty’; ‘Hardest truth’ for Africa’s energy transition appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Q&A: What Trump’s US exit from UNFCCC and IPCC could mean for climate action

The Trump administration in the US has announced its intention to withdraw from the UN’s landmark climate treaty, alongside 65 other international bodies that “no longer serve American interests”.

Every nation in the world has committed to tackling “dangerous anthropogenic interference with the climate system” under the 1992 UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC).

During Donald Trump’s second presidency, the US has already failed to meet a number of its UN climate treaty obligations, including reporting its emissions and funding the UNFCCC – and it has not attended recent climate summits.

However, pulling out of the UNFCCC would be an unprecedented step and would mark the latest move by the US to disavow global cooperation and climate action.

Among the other organisations the US plans to leave is the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), the UN body seen as the global authority on climate science.

In this article, Carbon Brief considers the implications of the US leaving these bodies, as well as the potential for it rejoining the UNFCCC in the future.

Carbon Brief has also spoken to experts about the contested legality of leaving the UNFCCC and what practical changes – if any – will result from the US departure.

- What is the process for pulling out of the UNFCCC?

- Is it legal for Trump to take the US out of the UNFCCC unilaterally?

- How could the US rejoin the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement?

- What changes when the US withdraws from the UNFCCC?

- What about the US withdrawal from the IPCC?

- What other organisations are affected?

What is the process for pulling out of the UNFCCC?

The Trump administration set out its intention to withdraw from the UNFCCC and the IPCC in a White House presidential memorandum issued on 7 January 2026.

It claims authority “vested in me as president by the constitution and laws of the US” to withdraw the country from the treaty, along with 65 other international and UN bodies.

However, the memo includes a caveat around its instructions, stating:

“For UN entities, withdrawal means ceasing participation in or funding to those entities to the extent permitted by law.”

(In an 8 January interview with the New York Times, Trump said he did not “need international law” and that his powers were constrained only by his “own morality”.)

The US is the first and only country in the world to announce it wants to withdraw from the UNFCCC.

The convention was adopted at the UN headquarters in New York in May 1992 and opened for signatures at the Rio Earth summit the following month. The US became the first industrialised nation to ratify the treaty that same year.

It was ultimately signed by every nation on Earth – making it one of the most ratified global treaties in history.

Article 25 of the treaty states that any party may withdraw by giving written notification to the “depositary”, which is elsewhere defined as being the UN secretary general – currently, António Guterres.

The article, shown below, adds that the withdrawal will come into force a year after a written notification is supplied.

The treaty adds that any party that withdraws from the convention shall be considered as also having left any related protocol.

The UNFCCC has two main protocols: the Kyoto Protocol of 1997 and the Paris Agreement of 2015.

Although former US president Bill Clinton signed the Kyoto Protocol in 1998, its formal ratification faced opposition from the Senate and the treaty was ultimately rejected by his successor, president George W Bush, in 2001.

Domestic opposition to the protocol centred around the exclusion of major developing countries, such as China and India, from emissions reduction measures.

The US did ratify the Paris Agreement, but Trump signed an executive order to take the nation out of the pact for a second time on his first resumed day in office in January 2025.

Is it legal for Trump to take the US out of the UNFCCC unilaterally?

Whether Trump can legally pull the US out of the UNFCCC without the consent of the Senate remains unclear.

The US previously left the Paris Agreement during Trump’s first term.

Both the UNFCCC and the Paris Agreement allow any party to withdraw with a year’s written notice. However, both treaties state that parties cannot withdraw within the first three years of ratification.

As such, the first Trump administration filed notice to exit the Paris Agreement in November 2019 and became the first nation in the world to formally leave a year later – the day after Democrat Joe Biden won the 2020 presidential election.

On his first day in office in 2021, Biden rejoined the Paris Agreement. This took 30 days from notifying the UNFCCC to come into force.

The legalities of leaving the UNFCCC are murkier, due to how it was adopted.

As Michael B Gerrard, director of the Sabin Center for Climate Change Law at Columbia Law School, explains to Carbon Brief, the Paris Agreement was ratified without Senate approval.

Article 2 of the US Constitution says presidents have the power to make or join treaties subject to the “advice and consent” of the Senate – including a two-thirds majority vote (see below).

However, Barack Obama took the position that, as the Paris Agreement “did not impose binding legal obligations on the US, it was not a treaty that required Senate ratification”, Gerrard tells Carbon Brief.

As noted in a post by Jake Schmidt, a senior strategic director at the environmental NGO Natural Resources Defense Council (NRDC), the US has other mechanisms for entering international agreements. It says the US has joined more than 90% of the international agreements it is party to through different mechanisms.

In contrast, George H Bush did submit the UNFCCC to the Senate in 1992, where it was unanimously ratified by a 92-0 vote, ahead of his signing it into law.

Reversing this is uncertain legal territory. Gerrard tells Carbon Brief:

“There is an open legal question whether a president can unilaterally withdraw the US from a Senate-ratified treaty. A case raising that question reached the US Supreme Court in 1979 (Goldwater vs Carter), but the Supreme Court ruled this was a political question not suitable for the courts.”

Unlike ratifying a treaty, the US Constitution does not explicitly specify whether the consent of the Senate is required to leave one.

This has created legal uncertainty around the process.

Given the lack of clarity on the legal precedent, some have suggested that, in practice, Trump can pull the US out of treaties unilaterally.

Sue Biniaz, former US principal deputy special envoy for climate and a key legal architect of the Paris Agreement, tells Carbon Brief:

“In terms of domestic law, while the Supreme Court has not spoken to this issue (it treated the issue as non-justifiable in the Goldwater v Carter case), it has been US practice, and the mainstream legal view, that the president may constitutionally withdraw unilaterally from a treaty, ie without going back to the Senate.”

Additionally, the potential for Congress to block the withdrawal from the UNFCCC and other treaties is unclear. When asked by Carbon Brief if it could play a role, Biniaz says:

“Theoretically, but politically unlikely, Congress could pass a law prohibiting the president from unilaterally withdrawing from the UNFCCC. (The 2024 NDAA contains such a provision with respect to NATO.) In such case, its constitutionality would likely be the subject of debate.”

How could the US rejoin the UNFCCC and Paris Agreement?

The US would be able to rejoin the UNFCCC in future, but experts disagree on how straightforward the process would be and whether it would require a political vote.

In addition to it being unclear whether a two-thirds “supermajority” vote in the Senate is required to leave a treaty, it is unclear whether rejoining would require a similar vote again – or if the original 1992 Senate consent would still hold.

Citing arguments set out by Prof Jean Galbraith of the University of Pennsylvania law school, Schmidt’s NRDC post says that a future president could rejoin the convention within 90 days of a formal decision, under the merit of the previous Senate approval.

Biniaz tells Carbon Brief that there are “multiple future pathways to rejoining”, adding:

“For example, Prof Jean Galbraith has persuasively laid out the view that the original Senate resolution of advice and consent with respect to the UNFCCC continues in effect and provides the legal authority for a future president to rejoin. Of course, the Senate could also give its advice and consent again. In any case, per Article 23 of the UNFCCC, it would enter into force for the US 90 days after the deposit of its instrument.”

Prof Oona Hathaway, an international law professor at Yale Law School, believes there is a “very strong case that a future president could rejoin the treaty without another Senate vote”.

She tells Carbon Brief that there is precedent for this based on US leaders quitting and rejoining global organisations in the past, explaining:

“The US joined the International Labour Organization in 1934. In 1975, the Ford administration unilaterally withdrew, and in 1980, the Carter administration rejoined without seeking congressional approval.

“Similarly, the US became a member of the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) in 1946. In the 1980s, the Reagan administration unilaterally withdrew the US. The Bush administration rejoined UNESCO in 2002, but in 2019 the Trump administration once again withdrew. The Biden administration rejoined in 2023, and the Trump Administration announced its withdrawal again in 2025.”

But this “legal theory” of a future US president specifically re-entering the UNFCCC “based on the prior Senate ratification” has “never been tested in court”, Prof Gerrard from Columbia Law School tells Carbon Brief.

Dr Joanna Depledge, an expert on global climate negotiations and research fellow at the University of Cambridge, tells Carbon Brief:

“Due to the need for Senate ratification of the UNFCCC (in my interpretation), there is no way back now for the US into the climate treaties. But there is nothing to stop a future US president applying [the treaty] rules or – what is more important – adopting aggressive climate policy independently of them.”

If it were required, achieving Senate approval to rejoin the UNFCCC would take a “significant shift in US domestic politics”, public policy professor Thomas Hale from the University of Oxford notes on Bluesky.

Rejoining the Paris Agreement, on the other hand, is a simpler process that the US has already undertaken in recent years. (See: Is it legal for Trump to take the US out of the UNFCCC unilaterally?) Biniaz explains:

“In terms of the Paris Agreement, a party to that agreement must also be a party to the UNFCCC (Article 20). Assuming the US had rejoined the UNFCCC, it could rejoin the Paris Agreement as an executive agreement (as it did in early 2021). The agreement would enter into force for the US 30 days after the deposit of its instrument (Article 21).”

The Center for Climate and Energy Solutions, an environmental non-profit, explains that Senate approval was not required for Paris “because it elaborates an existing treaty” – the UNFCCC.

What changes when the US withdraws from the UNFCCC?

US withdrawal from the UNFCCC has been described in media coverage as a “massive hit” to global climate efforts that will “significantly limit” the treaty’s influence.

However, experts tell Carbon Brief that, as the Trump administration has already effectively withdrawn from most international climate activities, this latest move will make little difference.

Moreover, Depledge tells Carbon Brief that the international climate regime “will not collapse” as a result of US withdrawal. She says:

“International climate cooperation will not collapse because the UNFCCC has 195 members rather than 196. In a way, the climate treaties have already done their job. The world is already well advanced on the path to a lower-carbon future. Had the US left 10 years ago, it would have been a serious threat, but not today. China and other renewable energy giants will assert even more dominance.”

Depledge adds that while the “path to net-zero will be longer because of the drastic rollback of domestic climate policy in the US”, it “won’t be reversed”.

Technically, US departure from the UNFCCC would formally release it from certain obligations, including the need to report national emissions.

As the world’s second-largest annual emitter, this is potentially significant.

“The US withdrawal from the UNFCCC undoubtedly impacts on efforts to monitor and report global greenhouse gas emissions,” Dr William Lamb, a senior researcher at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK), tells Carbon Brief.

Lamb notes that while scientific bodies, such as the IPCC, often use third-party data, national inventories are still important. The US already failed to report its emissions data last year, in breach of its UNFCCC treaty obligations.

Robbie Andrew, senior researcher at Norwegian climate institute CICERO, says that it will currently be possible for third-party groups to “get pretty close” to the carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions estimates previously published by the US administration. However, he adds:

“The further question, though, is whether the EIA [US Energy Information Administration] will continue reporting all of the energy data they currently do. Will the White House decide that reporting flaring is woke? That even reporting coal consumption is an unnecessary burden on business? I suspect the energy sector would be extremely unhappy with changes to the EIA’s reporting, but there’s nothing at the moment that could guarantee anything at all in that regard.”

Andrew says that estimating CO2 emissions from energy is “relatively straightforward when you have detailed energy data”. In contrast, estimating CO2 emissions from agriculture, land use, land-use change and forestry, as well as other greenhouse gas emissions, is “far more difficult”.

The US Treasury has also announced that the US will withdraw from the UN’s Green Climate Fund (GCF) and give up its seat on the board, “in alignment” with its departure from the UNFCCC. The Trump administration had already cancelled $4bn of pledged funds for the GCF.

Another specific impact of US departure would be on the UNFCCC secretariat budget, which already faces a significant funding gap. US annual contributions typically make up around 22% of the body’s core budget, which comes from member states.

However, as with emissions data and GCF withdrawal, the Trump administration had previously indicated that the US would stop funding the UNFCCC.

In fact, billionaire and UN special climate envoy Michael Bloomberg has already committed, alongside other philanthropists, to making up the US shortfall.

Veteran French climate negotiator Paul Watkinson tells Carbon Brief:

“In some ways the US has already suspended its participation. It has already stopped paying its budget contributions, it sent no delegation to meetings in 2025. It is not going to do any reporting any longer – although most of that is now under the Paris Agreement. So whether it formally leaves the UNFCCC or not does not change what it is likely to do.”

Dr Joanna Depledge tells Carbon Brief that she agrees:

“This is symbolically and politically huge, but in practice it makes little difference, given that Trump had already announced total disengagement last year.”

The US has a history of either leaving or not joining major environmental treaties and organisations, such as the Paris Agreement and the Kyoto Protocol. (See: What is the process for pulling out of the UNFCCC?)

Dr Jennifer Allan, a global environmental politics researcher at Cardiff University, tells Carbon Brief:

“The US has always been an unreliable partner…Historically speaking, this is kind of more of the same.”

The NRDC’s Jake Schmidt tells Carbon Brief that he doubts US absence will lead to less progress at UN climate negotiations. He adds:

“[The] Trump team would have only messed things up, so not having them participate will probably actually lead to better outcomes.”

However, he acknowledges that “US non-participation over the long-term could be used by climate slow-walking countries as an excuse for inaction”.

Biniaz tells Carbon Brief that the absence of the US is unlikely to unlock reform of the UN climate process – and that it might make negotiations more difficult. She says:

“I don’t see the absence of the US as promoting reform of the COP process. While the US may have had strong views on certain topics, many other parties did as well, and there is unlikely to be agreement among them to move away from the consensus (or near consensus) decision-making process that currently prevails. In fact, the US has historically played quite a significant ‘broker’ role in the negotiations, which might actually make it more difficult for the remaining parties to reach agreement.”

After leaving the UNFCCC, the US would still be able to participate in UN climate talks as an observer, albeit with diminished influence. (It is worth noting that the US did not send a delegation to COP30 last year.)

There is still scope for the US to use its global power and influence to disrupt international climate processes from the outside.

For example, last year, the Trump administration threatened nations and negotiators with tariffs and withdrawn visa rights if they backed an International Maritime Organization (IMO) effort to cut shipping emissions. Ultimately, the measures were delayed due to a lack of consensus.

(Notably, the IMO is among the international bodies that the US has not pledged to leave.)

What about the US withdrawal from the IPCC?

As a scientific body, rather than a treaty, there is no formal mechanism for “withdrawing” from the IPCC. In its own words, the IPCC is an “organisation of governments that are members of the UN or World Meteorological Organization” (WMO).

Therefore, just being part of the UN or WMO means a country is eligible to participate in the IPCC. If a country no longer wishes to play a role in the IPCC, it can simply disengage from its activities – for example, by not attending plenary meetings, nominating authors or providing financial support.

This is exactly what the US government has been doing since last year.

Shortly before the IPCC’s plenary meeting for member governments – known as a “session” – in Hangzhou, China, in March 2025, reports emerged that US officials had been denied permission to attend.

In addition, the contract for the technical support unit for Working Group III (WG3) was terminated by its provider, NASA, which also eliminated the role of chief scientist – the position held by WG3 co-chair Dr Kate Cavlin.

(Each of the IPCC’s three “working groups” has a technical support unit, or TSU, which provides scientific and operational support. These are typically “co-located” between the home countries of a working group’s two co-chairs.)

The Hangzhou session was the first time that the US had missed a plenary since the IPCC was founded in 1988. It then missed another in Lima, Peru, in October 2025.

Although the US government did not nominate any authors for the IPCC’s seventh assessment cycle (AR7), US scientists were still put forward through other channels. Analysis by Carbon Brief shows that, across the three AR7 working group reports, 55 authors are affiliated with US institutions.

However, while IPCC authors are supported by their institutions – they are volunteers and so are not paid by the IPCC – their travel costs for meetings are typically covered by their country’s government. (For scientists from developing countries, there is financial support centrally from the IPCC.)

Prof Chris Field, co-chair of Working Group II during the IPCC’s fifth assessment (AR5), tells Carbon Brief that a “number of philanthropies have stepped up to facilitate participation by US authors not supported by the US government”.

The US Academic Alliance for the IPCC – a collaboration of US universities and research institutions formed last year to fill the gap left by the government – has been raising funds to support travel.

In a statement reacting to the US withdrawal, IPCC chair Prof Sir Jim Skea said that the panel’s focus remains on preparing the reports for AR7:

“The panel continues to make decisions by consensus among its member governments at its regular plenary sessions. Our attention remains firmly on the delivery of these reports.”

The various reports will be finalised, reviewed and approved in the coming years – a process that can continue without the US. As it stands, the US government will not have a say on the content and wording of these reports.

Field describes the US withdrawal as a “self-inflicted wound to US prestige and leadership” on climate change. He adds:

“I don’t have a crystal ball, but I hope that the US administration’s animosity toward climate change science will lead other countries to support the IPCC even more strongly. The IPCC is a global treasure.”

The University of Edinburgh’s Prof Gabi Hegerl, who has been involved in multiple IPCC reports, tells Carbon Brief:

“The contribution and influence of US scientists is presently reduced, but there are still a lot of enthusiastic scientists out there that contribute in any way they can even against difficult obstacles.”

On Twitter, Prof Jean-Pascal van Ypersele – IPCC vice-chair during AR5 – wrote that the US withdrawal was “deeply regrettable” and that to claim the IPCC’s work is contrary to US interests is “simply nonsensical”. He continued:

“Let us remember that the creation of the IPCC was facilitated in 1988 by an agreement between Ronald Reagan and Margaret Thatcher, who can hardly be described as ‘woke’. Climate and the environment are not a matter of ideology or political affiliation: they concern everyone.”

Van Ypersele added that while the IPCC will “continue its work in the service of all”, other countries “will have to compensate for the budgetary losses”.

The IPCC’s most recent budget figures show that the US did not make a contribution in 2025.

Carbon Brief analysis shows that the US has provided around 30% of all voluntary contributions in the IPCC’s history. Totalling approximately $67m (£50m), this is more than four times that of the next-largest direct contributor, the EU.

However, this is not the first time that the US has withdrawn funding from the IPCC. During Trump’s first term of office, his administration cut its contributions in 2017, with other countries stepping up their funding in response. The US subsequently resumed its contributions.

At its most recent meeting in Lima, Peru, in October 2025, the IPCC warned of an “accelerating decline” in the level of annual voluntary contributions from countries and other organisations, reported the Earth Negotiations Bulletin. As a result, the IPCC invited member countries to increase their donations “if possible”.

What other organisations are affected?

In addition to announcing his plan to withdraw the US from the UNFCCC and the IPCC, Trump also called for the nation’s departure from 16 other organisations related to climate change, biodiversity and clean energy.

These include:

- The Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) – the biodiversity equivalent of the IPCC.

- Intergovernmental Forum on Mining, Minerals, Metals and Sustainable Development – a voluntary group of more than 80 countries aiming to make the mining sector more sustainable.

- UN Energy – the principal UN organisation for international collaboration on energy.

- UN Oceans – a UN mechanism responsible for overseeing the International Seabed Authority (ISA) and other UN agencies related to ocean and coastal issues.

- UN Water – the UN agency responsible for water and sanitation.

- UN Collaborative Programme on Reducing Emissions from Deforestation and Forest Degradation in Developing Countries (UN-REDD) – a UN collaborative initiative for creating financial incentives for protecting forests.

- International Renewable Energy Agency – an intergovernmental organisation supporting countries in their transition to renewable energy.

- 24/7 Carbon-Free Energy Compact – a UN initiative launched in 2021 pushing governments, companies and organisations to achieve 100% low-carbon electricity generation.

- Commission for Environmental Cooperation – an organisation aimed at conserving North America’s natural environment.

- Inter-American Institute for Global Change Research – an intergovernmental organisation supported by 19 countries in North and South America for the support of planetary change research.

- International Energy Forum – an intergovernmental platform for dialogue among countries, industry and experts.

- International Solar Alliance – an organisation supporting the development of solar power and the phaseout of fossil fuels.

- International Tropical Timber Organization – an organisation aimed at protecting tropical forest resources.

- International Union for Conservation of Nature – an international nature conservation organisation and authority on the state of biodiversity loss.

- Renewable Energy Policy Network for the 21st Century – a global policy forum for renewable energy leadership.

- Secretariat of the Pacific Regional Environment Programme – a regional organisation aimed at protecting the Pacific’s environment.

As well as participating in the work of these organisations, the US is also a key source of funding for many of them – leaving their futures uncertain.

In a letter to members seen by Carbon Brief, IPBES chair and Kenyan ecologist, Dr David Obura, described Trump’s move as “deeply disappointing”.

He said that IPBES “has not yet received any formal notification” from the US, but “anticipates that the intention expressed to withdraw will mean that the US will soon cease to be a member of IPBES”, adding:

“The US is a founding member of IPBES and scientists, policymakers and stakeholders – including Indigenous peoples and local communities – from the US have been among the most engaged contributors to the work of IPBES since its establishment in 2012, making valuable contributions to objective science-based assessments of the state of the planet, for people and nature.

“The contribution of US experts ranges from leading landmark assessment reports, to presiding over negotiations, serving as authors and reviewers, as well as helping to steer the organisation both scientifically and administratively.”

Despite being a party to IPBES until now, the US has never been a signatory to the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), the nature equivalent of the UNFCCC.

It is one of only two nations not to sign the convention, with the other being the Holy See, representing the Vatican City.

The lack of US representation at the CBD has not prevented countries from reaching agreements. In 2022, countries gathered under the CBD adopted the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework, often described as the “Paris Agreement for nature”.

However, some observers have pointed to the lack of US involvement as one of the reasons why biodiversity loss has received less international attention than climate change.

The post Q&A: What Trump’s US exit from UNFCCC and IPCC could mean for climate action appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: What Trump’s US exit from UNFCCC and IPCC could mean for climate action

-

Climate Change5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits