Crops that have been “altered” by scientists in a laboratory can be found growing on millions of hectares of farmland around the world.

These “genetically modified organisms” (GMOs) are planted extensively across swathes of North and South America, in particular, but remain strictly limited in many countries.

However, these stringent regulations have eased in some nations for crops altered using new, more precise “gene-editing” technologies.

Several experts tell Carbon Brief that these new technologies are not a “silver-bullet” solution for agriculture, but that they could help crops deal with extreme weather and boost nutrition in a faster, safer and cheaper way than GMOs.

In contrast, other experts, as well as environmental groups, are concerned about how these gene-edited crops will be produced, regulated and patented.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief looks at the difference between GMOs and gene-edited foods and whether these technologies can help crops deal with climate change while boosting food security.

- What are genetically modified crops?

- Where are genetically modified and gene-edited crops grown around the world?

- What are the perceived benefits and concerns of genetically engineered foods?

- Could gene-editing and GMOs benefit food security?

- Do genetically modified crops benefit climate mitigation and adaptation?

What are genetically modified crops?

For centuries, farmers have used selective breeding techniques to prioritise growing crops with desirable traits, such as resistance to disease.

In the 1970s, scientists developed new ways to boost these traits directly by changing a plant’s genetic material.

GMOs – genetically modified organisms – are plants, animals and microorganisms whose genes have been altered with the help of technology.

Dr Jennifer Pett-Ridge is a senior researcher at the Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory and principal investigator on a soil carbon project at the Innovative Genomics Institute in Berkeley, California.

She explains that gene modification technologies take DNA from one species and insert it into another. She tells Carbon Brief:

“It might be a frog or a tomato, or something like that, that you’re importing from another organism that has a trait that you really want that will work within your organism of choice. You’re splicing that in, essentially.”

The most common traits scientists put into genetically modified crops include tolerance to weed-killing herbicides and resistance to insects and viruses. The techniques can also be used to develop plants that are better able to deal with drought, heat and other intensifying effects of climate change.

In the US in 1994 – after years of testing and experiments – a GM tomato was the world’s first genetically engineered food sold in shops, according to the country’s Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

This tomato was “genetically altered to ripen longer on the vine while remaining firm for picking and shipping”, the New York Times reported at the time.

Two years later, farmers began growing genetically engineered crops across the US. One example is “Roundup Ready” maize, cotton and other crops. These plants were developed by the chemical company Monsanto – which was bought out by Bayer in 2018 – to be more resistant to the weed-killer Roundup.

A gene that is resistant to glyphosate – the herbicide used in Roundup – was taken from a type of bacteria and inserted into these crops. This, in turn, allowed farmers to apply the herbicide to kill weeds without destroying their crops.

In more recent years, scientists have developed different ways to alter DNA. One prevailing method is Crispr/Cas9 – a gene-editing technology that can tweak genetic code without needing to introduce traits from another species. The scientists behind the discovery were awarded a Nobel Prize in 2020.

The method is akin to using a “pair of scissors to just snip a gene out and move it somewhere else” within the same plant, Pett-Ridge says, preventing the need to mix in DNA from other species, which is how GMOs are made.

For example, the technology could be used to remove a gene that makes a plant less able to deal with drought.

A 2016 study on the possibilities of Crispr for plants described the technology as relatively simple, cheap and versatile compared to other methods. So far, scientists have carried out studies on the method’s ability to alter the genetic make-up of a wide range of crops, from rice and tomatoes, to oranges and maize.

However, these trials are in the early stages of development and experts tell Carbon Brief more research is needed before they are widely commercially available.

New technologies such as Crispr are being regulated differently to other GMOs in many countries, but opinions differ on how different they truly are from older genetic-engineering techniques.

Although there is limited evidence showing that GMOs have a negative effect on human health and the environment, they remain controversial for many due to concerns over reduced biodiversity and the prevalence of crop monocultures.

Where are genetically modified and gene-edited crops grown around the world?

Genetically modified crops are widely grown in some parts of the world, such as the US and parts of South America, and are more restricted in the EU and many African countries.

In 2019, more than 190m hectares of genetically modified crops were planted around the world – an area roughly the size of Mexico – according to the International Service for the Acquisition of Agri-biotech Applications.

In 1996, around the time GM crops were being approved for commercial use in several countries, this figure stood at 1.7m hectares.

The US grows the most GM crops of any country, followed by Brazil, Argentina, Canada and India – as shown in the figure below.

Almost all soya beans, cotton and maize now planted in the US are genetically modified, often to resist pests or deal with herbicide use, according to the FDA.

Alongside feeding people, GM maize and soya beans are frequently used to feed animals. More than 95% of livestock and poultry in the US eat genetically modified crops, the FDA says.

In the EU and other parts of the world, GM crops are not widely grown. The EU’s rules require GMO foods to be labelled as such for consumers and permit individual EU countries to ban genetically modified crops, if they choose. Most EU countries do not grow GMO crops.

The EU’s GMO rules still apply in the UK. But, in 2023, the rules in England were eased to allow the development of plants that are genetically edited using modern methods such as Crispr.

Further laws are needed to allow these gene-edited plants – and, later, animals – to be sold in England. The legislation for plants is set to be brought in this summer.

Rules around whether these gene-edited plants should be treated the same as, or differently to, GMOs are still being assessed by many governments around the world.

In some countries, such as the US, they are essentially treated the same as non-GMO products. Since they do not contain “foreign” genes, they are seen as indistinguishable from conventional plants.

The EU could be moving in a similar direction with a proposal from the European Commission to loosen its stringent GMO requirements for plants that have been made using newer gene-editing technologies.

The changes would “better reflect the different risk profiles” of the way in which gene-edited plants are made compared to genetically modified ones, the commission said.

Dr Ludivine Petetin, a reader in law and expert in agri-food issues at Cardiff University, says the proposal marks a significant change from the EU’s previous attitude to genetically altered foods.

If approved, the EU would create two categories of plants that have been altered by new genomic techniques. One category of plants would be considered comparable to conventional plants and would not require any GMO labelling for consumers.

Plants that have been made using these newer techniques, but do not meet this criteria, would fall into the second category. This would require stricter assessment and mandatory labelling, similar to how GMOs are currently regulated in the EU. Petetin tells Carbon Brief:

“That’s a massive, massive difference to the precautionary principle used before, where it was all about the need to inform the public – the need to tell them whether there is [genetic modification] or not in what we are all eating.”

The “precautionary principle” approach is used to apply caution to issues that have uncertain levels of scientific evidence about a risk to environmental or human health. It is used in the EU’s directive on GMOs.

The debate around the EU’s proposal is on hold until after the European parliament elections in June.

Earlier this year, more than 1,500 scientists and 37 Nobel Prize winners signed an open letter calling on EU politicians to support gene-editing techniques and “consider the unequivocal body of scientific evidence supporting” new genomic techniques.

What are the perceived benefits and concerns of genetically engineered foods?

Proponents of GMOs highlight that they can boost crop yields and help feed the expanding global population. Critics point to human and environmental concerns.

A 2022 study found that the “right use” of GM crops could potentially “offer more benefit than harm, with its ability to alleviate food crises around the world”, based on a review of different impacts of GM crops on “sustainable agriculture” systems.

The main concerns laid out by the World Health Organization are triggering allergens, raising antibiotic resistance and spillover of GM plants into land that is growing conventional crops.

This spillover could reduce the diversity of crops being grown and lead to monocultures of plants, which can degrade soils and reduce biodiversity.

Other concerns focus on the use of pesticides and herbicides. A 2023 review study said that some areas growing herbicide-tolerant crops sometimes use more of the plant-killing chemical due to the emergence of herbicide-resistant weeds.

Nonetheless, the study found that, overall, genetically modified crops have had a positive impact on crop yields, pest and disease resistance and tolerance to stresses such as high temperatures or drought.

A 2017 study said there is evidence that GM crops can have negative environmental impacts, such as harming biodiversity. But this – and other studies – have concluded that further research is still needed on the human and environmental health risks of GM plants.

Other criticisms around GMOs and gene-edited crops centre around how they are regulated. Patenting is one of these concerns.

In the US, Brazil and other countries, GMO seeds can be patented. The global seed market, in general, is dominated by a small number of companies, such as Bayer and Corteva. The chart below shows that these two companies control 40% of the global seed market.

Petetin says that if seed patenting is permitted under the EU’s gene-editing rules, as currently proposed, it could lead to “more concentration of the seeds and the plant business”.

Experts tell Carbon Brief that the patenting of these seeds impacts farmers as they often have to re-purchase GM seeds each year from a company which has complete control over the cost.

The price of GM seeds rose by more than 700% between 2000 and 2015. A number of large seed companies have taken farmers to court for infringing on patent rights by growing GM crops without payment.

Patenting can also pose problems for small-scale seed developers, as similarities with patented crops can also lead to infringement claims. This can apply to both genetically modified and conventional crops.

Eva Corral, a GMO campaigner at Greenpeace EU, is calling for more information on the climate, health and environmental impacts of gene-edited foods and for labelling to remain in place in the EU’s rules.

She tells Carbon Brief that gene-edited crops are not a “panacea” to “miraculously solve all the problems in the world”, adding:

“We have to be really very, very cautious, which I think is something very much missing in the debate about new GMOs.”

Could gene-editing and GMOs benefit food security?

Whether through traditional breeding or by scientists in a lab, crops are often altered to make them more resistant to drought, better able to fight off disease or to improve their nutritional value.

All of these elements could be helpful for farmers around the world whose crops are being damaged by extreme weather conditions fuelled by human-caused climate change.

Disasters – such as floods, droughts and wildfires – have caused about $3.8tn worth of lost crops and livestock production over the past three decades, according to a report by the UN Food and Agriculture Organization.

Genetically modified crops can increase the amount of food grown in a certain amount of space – which is significant given that the amount of arable land around the world is declining.

Global crop production grew by more than 370m tonnes between 1996 and 2012. Genetically modified crops in the US accounted for one-seventh of this boost.

Increased crop yields and reduced losses due to extreme weather can be particularly attractive for countries hit by high levels of hunger and facing severe impacts of climate change.

Between 691 and 783 million people faced hunger in 2022, according to the UN’s 2023 report on food security and nutrition. The issue is particularly acute in Africa, where around one in five people face hunger – a “much larger” amount than the rest of the world, the report says.

Several experts tell Carbon Brief that scientists have long-hoped that Crispr’s relatively low cost and simpler technology would enable more gene-edited crop development in developing countries.

In African countries, GM and gene-edited crops could be part of the solution, but are not the only fix to problems facing agriculture, such as drought and poor crop yields, says Prof Ademola Adenle, a guest professor of sustainability science at the Technical University of Denmark. He tells Carbon Brief:

“Just like GMOs, gene-editing is not a silver-bullet solution to hunger or food security problems or climate change. But it could be part of a solution to a wide range of problems in the agricultural sector and [have] the potential to create crops that are resistant to diseases.”

Adenle, who is from Nigeria, has researched the progress in regulation and development of GM crops in different parts of Africa. GM crops are commercially grown in South Africa and a small number of other countries on the continent, such as Kenya and Nigeria.

He tells Carbon Brief that more research is needed to inform ongoing GMO and gene-editing discussions in African countries:

“Without investment in research and development programmes, Africa will be left behind…in terms of applying new technologies to solve some of the problems we have in the agricultural sector.

“Before gene-editing can be accepted in Africa, just like GMO, [countries] have to have the scientific capacity, they have to have the policy in place and, of course, they need to raise the level of awareness about the advantages and perhaps disadvantages that may be associated with the application of gene editing.”

Dr Joeva Sean Rock, an assistant professor in development studies at the University of Cambridge, has researched the politics of GM foods in Africa, particularly Ghana.

She says there is “a lot of hype” around the potential uses of gene-editing to develop crops that can “improve climate resilience and food security”. But she urges caution, telling Carbon Brief:

“An important question becomes how that hype compares with present reality…We are in a moment where there’s a real opportunity to ask not necessarily whether this technology could be a panacea, but rather if and how it might be able to benefit people at different scales and with different needs.”

A recent study found that a relatively small number of gene-editing crop projects focus on benefitting smallholder farmers in the global south. These farmers are “exceptionally vulnerable to climate change and food insecurity”, Rock says, adding:

“Farmers have diverse needs and so an important question is whether genome editing is an appropriate tool to address those needs and whether it is being used to do so.”

Do genetically modified crops benefit climate mitigation and adaptation?

There have been a lot of claims – and counter-claims – about the climate benefits of GMOs, both in terms of making crops more resistant to extreme weather and in helping plants to absorb more carbon from the atmosphere.

Dr Emma Kovak is a senior food and agriculture analyst at the Breakthrough Institute – a controversial thinktank in California that claims it “promotes technological solutions to environmental and human development challenges”.

Kovak was the lead author of a 2022 study which said that growing more GM crops, such as wheat, in the EU could lead to reduced land-use emissions in other parts of the world. The researchers estimated the extent that greenhouse gas levels would be impacted by the EU growing similar levels of genetically modified maize, soya beans, cotton, canola and sugar beet as the US.

The study claimed that this increase in EU GMOs would boost crop yields, which would allow the bloc to provide more of its own crops, Kovak tells Carbon Brief. This could lead to emissions cuts equivalent to more than 7% of the EU’s greenhouse gas emissions from agriculture, the study found. Kovak says:

“Expansion of crop production through yield increases in the EU can decrease farmland expansion in other places in the world, which means less deforestation and emissions from deforestation.”

Agriculture drives at least three-quarters of deforestation around the world, with forests cleared to raise animals and grow crops such as soya beans.

Another study published in 2018 looked at the environmental impacts of GM crops, such as maize, cotton and soya beans, on pesticide use and CO2 emissions across different countries over 1996-2016.

The study combined previous studies on fuel use and tillage systems – that is, preparing the land for crops – along with evidence on the impact of GM crop usage on these practices. It also looked at farm-level and national pesticide usage surveys.

It found that the use of GM insect-resistant and herbicide-tolerant technology reduced pesticide spraying by 8%. This, as a result, reduced the environmental impacts of herbicide and insecticide use.

It further led to cuts in fuel use and tillage changes, resulting in a “significant reduction” in emissions from areas growing GM crops. Combining figures from reduced fuel use and increased soil carbon storage, the researchers said the emissions reduction would be equivalent to taking almost 17m cars off the road for one year.

A 2011 review study found that GM crops could reduce the impacts of agriculture on biodiversity in a number of ways, such as by reducing insecticide use and boosting crop yields to ease the pressure to transform more land to grow crops.

A 2021 study found a correlation between GM crop growth and use of the herbicide glyphosate with an increase in soil carbon sequestration in a province of Canada. However, herbicide use decreased soil biodiversity in banana fields in Martinique, a Caribbean island, a different study found.

When it comes to gene-edited plants, experts tell Carbon Brief that more research is needed to determine the possible climate benefits or negative impacts.

Studies on gene-edited crops remain in the early stages of development.

In terms of boosting carbon sequestration through soils, whether it is through gene-editing or conventional breeding, Pett-Ridge says that definitive results are still some distance away. She tells Carbon Brief:

“There is a lot of hype…there are folks out there saying that this can solve everything or we can fix our climate issues with soils. I would push back on that, while still saying it’s a significant opportunity.”

Targeting certain traits through gene-editing will “take some time before we can really assess whether those have a net benefit on the amount of carbon put in soil”, she adds:

“As much as I’m an optimist and excited about it… I don’t know anyone who has got traits focused on carbon capture really being applied even in a field trial.”

Petetin believes gene-editing may “provide some answers” to help the agriculture sector deal with extreme weather and other issues, but adds:

“They’re not the only answers to all the issues agriculture is facing with biodiversity and climate change emergencies. Putting all your eggs in this one basket is not the solution.”

The post Q&A: The evolving debate about using genetically modified crops in a warming world appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: The evolving debate about using genetically modified crops in a warming world

Climate Change

Q&A: What does the Iran war mean for the energy transition and climate action?

The US and Israel’s war on Iran has caused oil and gas prices to soar, with the world now preparing for the possibility of another energy crisis.

The conflict, which has seen Iran respond with missile strikes across the region, has killed more than 1,000 people so far and sent global markets into disarray.

With shipping through the critical Strait of Hormuz paralysed and direct attacks by both sides on fossil-fuel infrastructure, some of the world’s biggest oil and gas facilities have paused production.

On 9 March, oil prices soared above $100 per barrel for the first time since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, amid fears of long-term disruption to global energy supplies.

While US president Donald Trump has said that rising oil prices are a “very small price to pay” for “safety and peace”, the conflict is already pushing import-dependent countries to invoke emergency measures to protect consumers.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief looks at how the war has disrupted energy supplies, the impact on oil and gas prices, which parts of the world are being hit hardest and what it could mean for efforts by some to transition away from fossil fuels.

- How has the Iran war disrupted energy supplies?

- How has the Iran war impacted oil and gas prices?

- Which parts of the world have been most affected by the crisis?

- What does the Iran war mean for efforts to transition away from fossil fuels?

How has the Iran war disrupted energy supplies?

On 28 February, the US and Israel launched a large-scale military attack on Iran, which has responded with counterattacks across the region.

On 2 March, Iran said that it would attack any vessel travelling through the Strait of Hormuz, a narrow waterway used to transport around a quarter of global seaborne oil trade and a fifth of the world’s liquified natural gas (LNG) supply.

According to the UK’s maritime security agency, UKMTO, around 10 vessels have been attacked in or near the Strait of Hormuz since Iran’s threat.

Ship traffic through the Strait of Hormuz has since come to a “virtual standstill”.

While Saudi Arabia and the UAE can reroute some of their crude oil production via pipelines to avoid the strait, Kuwait, Qatar and Bahrain have no alternatives, according to Bloomberg.

As a result of the effective closure, oil storage facilities in the region are filling up. Saudi Arabia has started to reduce oil production, as there is limited storage and limited export options due to the strait remaining closed to shipping, reported Bloomberg.

Other energy infrastructure has also been caught in the crosshairs of the conflict, leading to site closures at a number of oil and gas facilities.

For example, Iranian drones targeted the giant Ras Laffan gas facility in Qatar, which is responsible for about a fifth of global LNG supply. The QatarEnergy facility subsequently paused production and “will take weeks to restart”, reported Reuters.

Additionally, Saudi Aramco paused work at one of its refineries due to a fire caused by debris from an intercepted drone attack. One of the largest oil storage terminals in the UAE halted operations and a range of other energy sites across the Middle East have ceased operations.

The combination of the effective closure of the Strait of Hormuz and disruption to energy infrastructure in the region has led to oil and gas prices surging to their highest levels in several years.

How has the Iran war impacted oil and gas prices?

Global oil and gas prices have been rising since the first US and Israel attacks on Iran in late February.

On 2 March, the Guardian reported that Brent crude – the global oil price benchmark – had risen by up to 13%, standing at a “14-month high” of $82 (£61) a barrel.

Experts at that stage warned that a prolonged closure of the Strait of Hormuz could continue to push up prices and lead to a “1970s-style energy shock”, according to CNBC.

By Monday 9 March, oil prices had soared above $100 (£74) per barrel for the first time since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022.

Prices hit $119 (£88) a barrel at one point on Monday, as shown in the chart below, amid fears of long-lasting disruption to global energy supplies.

US president Donald Trump called rising oil prices a “very small price to pay” for “safety and peace”, reported the Independent.

By Tuesday 10 March, the Guardian reported that the price of a barrel of oil had “tumbled” to around $91.70 (£68), after Trump suggested the war could end “very soon”.

(The Islamic Revolutionary Guards Corps said it would “determine the end of the war”, not “American forces”, reported France24.)

The price of gas has also risen across Europe and Asia.

Prices “soar[ed”, reported Al Jazeera, after LNG production was halted by Qatar’s state-run energy company. (See: How has the war disrupted energy supplies?)

This led to gas price jumps “amid concerns about supplies”, said the New York Times.

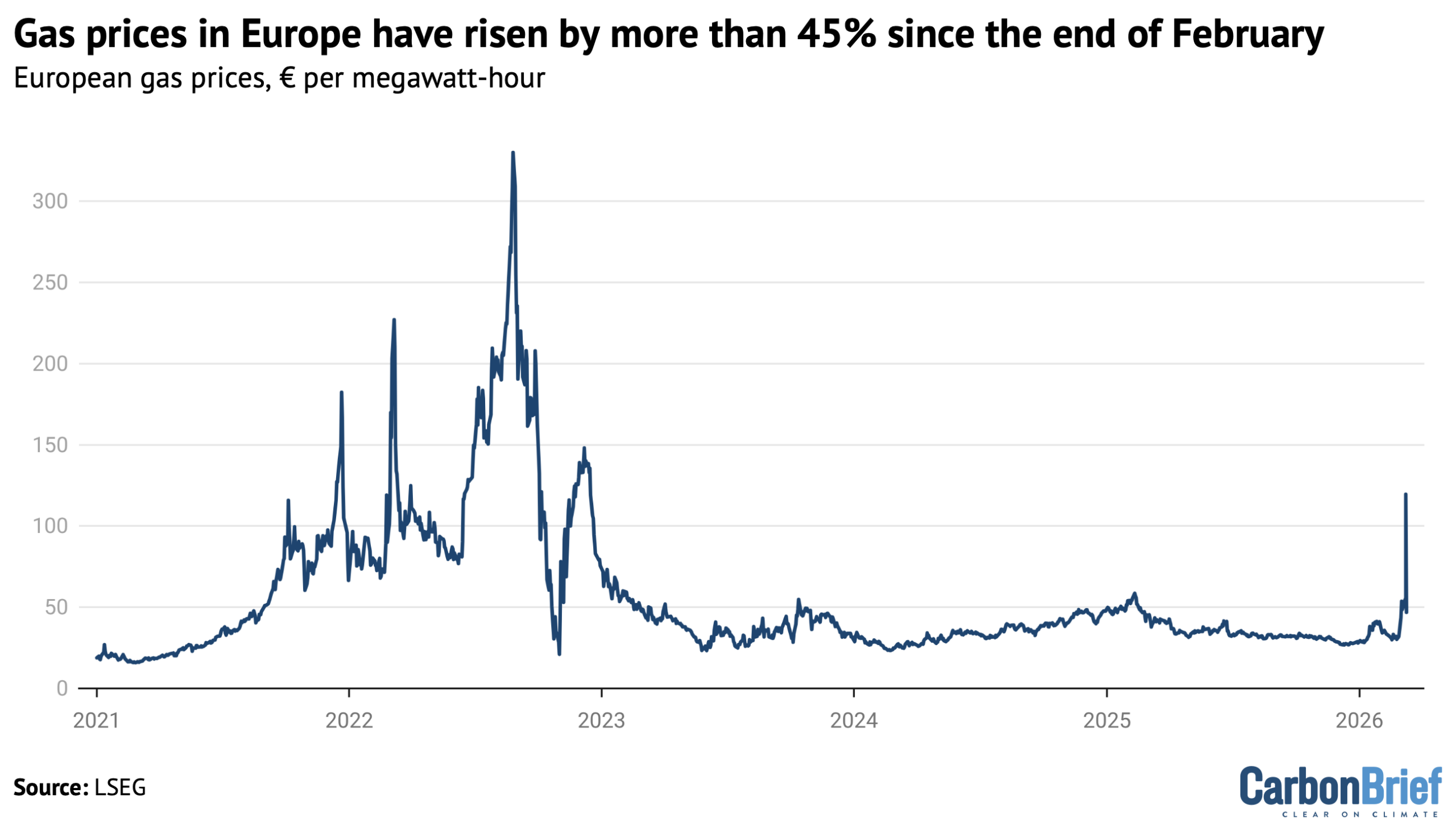

Subsequently, the price of gas in Europe rose by up to 45% to around €46 (£40) per megawatt hour (MWh) on 2 March.

European gas price futures increased by as much as 30% on 9 March, according to Bloomberg. Prices stood at around €60/MWh (£52/MWh) compared to a past peak in 2022 of above €300/MWh (£260/MWh), said the outlet.

Bloomberg noted that “prices are still well below the records reached” after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, as highlighted in the chart below.

Gas prices in Asia have more than doubled since 28 February, with some countries “struggling to find prompt” supplies.

In the UK, the price of gas has doubled since the start of the current conflict, although it has subsequently fallen back to around 75% above pre-crisis levels.

While domestic consumers are currently protected by the price cap for gas and electricity, some forecasts suggest bills could hit £2,500 a year – a rise of 50% – when the cap is updated in July. (There is currently no cap for consumers of heating oil.)

In the US, gas prices have only risen by 11% since the end of February, according to the Wall Street Journal. The US gas market is relatively insulated from global price spikes because it has limited export capacity. (The Wall Street Journal attributed this instead to “record” domestic production “cushioning” the country from the price jumps in other parts of the world.)

Meanwhile, the price of petrol (or “gas”, as it is known colloquially) in the US has increased by 19%, noted the New York Times. Even though the US is a net oil exporter, it is still affected by international price spikes, as the market for oil is globally interconnected.

The crisis has also raised the price of electricity, heating fuel, fertilisers, food and other products in many parts of the world.

Which parts of the world have been most affected by the crisis?

The impact of the Iran war has been felt around the world, in particular in areas reliant on oil and gas imports.

Below, Carbon Brief looks at how different regions have responded to the conflict so far.

Asia

Asia’s biggest economies are “highly dependent” on oil and gas imports that transit through the Strait of Hormuz, reported the Financial Times, adding that they are now “racing to secure new sources”. About 80% of all oil volumes through the strait go to Asia, according to the International Energy Agency (IEA).

East Asian nations, such as South Korea and Thailand, “have been hit especially hard” and have already announced measures such as capping petrol prices, according to BBC News. It said Vietnam plans to temporarily remove taxes on fuel imports and the Philippines has announced plans for a four-day working week for most public offices.

Reuters noted that Bangladesh “relies on imports for 95% of its energy needs” and has announced the early closure of all universities as part of emergency measures to conserve energy. The newswire says the country also halted operations at nearly all its state-run fertiliser factories, redirecting gas to power plants.

Myanmar, meanwhile, has announced a “sweeping fuel rationing system for private vehicles”, said another Reuters article.

On 9 March, China announced its “biggest retail fuel price cap increase in four years” for retail petrol and diesel, said Reuters. Additionally, diplomatic sources cited by Reuters said that China is “in talks with Iran to allow crude oil and Qatari liquefied natural gas vessels safe passage” through the Strait of Hormuz.

China is the main buyer of Iranian oil and has funded gas facilities in Qatar, meaning “billions of dollars are at risk from a widening war”, according to the New York Times.

However, India could be the “most vulnerable” to the war’s energy supply shock, according to the Hindustan Times.

On 3 March, India’s petroleum and natural gas minister Hardeep Singh Puri was quoted by the Economic Times saying that “India has sufficient reserves of crude oil and petroleum products to manage short-term disruptions”.

Three days later, the Hindustan Times reported that the US announced a “temporary 30-day waiver to Indian refineries” to continue to purchase Russian oil “already stranded at sea”. However, the Financial Times reported that analysts said that the crude oil freed up by this is a “drop in the ocean”, equivalent to only four days’ of Indian demand. (The New York Times said that the “dramatic change in energy markets could not have come at a better time for President Vladimir Putin of Russia”.)

India has invoked emergency measures to redirect supplies of liquefied petroleum gas “away from industrial users to households”, reported Bloomberg. Cooking gas supply and fertiliser plants have been given top priority, said the Times of India.

Middle East

Beyond the impact on energy, air and drone strikes in the Middle East have damaged key infrastructure, including water desalination plants.

The region is dependent on desalination plants for much of its drinking water. The Associated Press reported that, “in Kuwait, about 90% of drinking water comes from desalination, along with roughly 86% in Oman and about 70% in Saudi Arabia”.

It adds that “hundreds of desalination plants sit along the Persian Gulf coast, putting individual systems that supply water to millions [of people] within range of Iranian missile or drone strikes”.

The Financial Times noted that climate change is exacerbating water security concerns in the Gulf, where temperatures can exceed 50C in summer and there are “no permanent rivers”. It adds that climate change is “driving erratic rainfall patterns and contributing to low water storage” in the region.

The Middle East is also one of the world’s largest producers of fertilisers. Around 35% of the world’s exports of urea – a nitrogen fertiliser that “underpins around half of global food production” – passes through the Strait of Hormuz, according to the Financial Times.

As a result, the newspaper said that “granular urea prices in the Middle East have risen by about $130 to around $575-650 a tonne”.

The spike in the price of gas – a key element in fertiliser production – is also affecting fertiliser prices.

Europe

The disruption to global oil and gas supplies is driving up energy prices across Europe.

“The EU imports more than 90% of its oil and around 80% of its gas, making European countries highly exposed to fluctuations in global oil and gas prices,” according to Reuters. Europe’s gas market is particularly vulnerable at the moment, because it is emerging from winter with storage tanks depleted.

Bruegel said that Europe is “far less dependent on Gulf oil and LNG than China, India, Japan or South Korea”. However, it said that it is “not insulated”. It added:

“Oil and LNG are global markets: any blockage of the Strait of Hormuz could trigger immediate price spikes that would hit Europe regardless of its limited physical imports.”

The Financial Times reported that “European electricity prices are swinging wildly from daytime to evening as the Iran war’s disruption to gas supplies accentuates growing volatility in Europe’s power markets amid the rise of renewables”.

Petrol prices are also surging. UK average diesel costs have hit a 16-month high and the French government is asking a watchdog to check that petrol stations are not unfairly raising prices to profit from a rush for fuel.

Euronews reported EU leaders are “considering reviewing taxes, electricity network charges and carbon costs tied to energy prices as a quick fix for struggling industries”.

Meanwhile, EU economy and finance ministers gathered in Brussels to discuss how to respond to surging energy prices. According to Euronews, ministers have discussed the possibility of releasing oil reserves, but say that it is “not yet the right time”.

Other regions

Africa

In Africa, oil-producing Nigeria, Angola and Ghana are well-positioned to benefit from surging global prices, although the gains may not be evenly distributed. However, importing countries, such as South Africa, Kenya and the Democratic Republic of Congo, are at risk.

Every “$20 a barrel jump in Brent” could cause “a knock” of about 1% and 3% on South Africa and DRC’s GDP, respectively, according to Bloomberg analysis. Trade bottlenecks and the lack of refinery capacity in these countries could also lead to fuel shortages, it said.

While oil exporters could see windfall gains, “most African households will have to grapple with higher costs of living” since “most food and goods” are transported by road across the continent, noted the Associated Press.

The crisis, however, “may reinforce calls for African nations to diversify their energy systems and reduce dependence on imported fuels” through “long-term investments in renewable energy”, said Dr Kennedy Mbeva, research associate at Cambridge’s Centre for the Study of Existential Risk, as quoted in the story.

Australia

While Australia is a key gas and coal exporter, its dependence on petrol and diesel imports could leave it vulnerable, especially its agricultural and mining sectors.

The Australian Financial Review reported that Australia’s biggest gas producers – Santos and Woodside Energy – are “cashing in on the conflict…with deals struck at more than double recent market rates”.

Latin America

Major Latin American economies are “cautiously watching” the war’s impact on energy prices on their economies, reported El País.

The newspaper cited experts saying that for Venezuela – whose “modest but strategic share” of oil production is now under “direct scrutiny from the White House” – the crisis might result in additional revenues, to the tune of “around $2.4bn”.

It also quoted Mexico’s president, Claudia Sheinbaum, reassuring citizens that “compensation mechanisms [are] in place to prevent price increases from impacting” them.

While Brazil’s state-owned Petrobras “could benefit” from the crisis, said Reuters, the conflict “may spark grain contract cancellations and fertiliser shortages”.

Finally, a comment in Colombia One argued that the country’s “energy importance” could translate into “fiscal breathing room” and that oil gains could “financ[e] renewable energy without undermining fiscal stability”.

What does the Iran war mean for efforts to transition away from fossil fuels?

The rise in global fossil-fuel prices as a result of the war has prompted some leaders to recommit to boosting their energy sovereignty through the deployment of renewables.

Yet, the conflict has also been taken as an opportunity by supporters of fossil fuels to argue for more domestic oil-and-gas production, as a way to boost energy security.

In response to the crisis, Teresa Ribera, the executive vice-president of the European Commission who oversees the “clean, just and competitive transition”, said in a statement that the “answer is not new dependencies, but faster electrification, renewables and efficiency”, adding:

“The real risk is not moving too fast on clean energy, but too slowly. The clean transition is Europe’s shield against volatility.”

According to the South Korean newspaper Chosun Daily, the country’s president Lee Jae Myung said the crisis presented a “good opportunity to swiftly and extensively transition to renewable energy”.

In the UK, where there has been mounting pressure to relax government restrictions on the expansion of fossil-fuel extraction in the North Sea, prime minister Keir Starmer used a speech responding to the conflict in the Middle East to say:

“We…have the right plan for our energy supplies. Building up clean British energy like never before, decreasing our dependence on volatile international markets and creating the energy security and independence we need.”

Simon Stiell, the UN climate chief, said the crisis “shows yet again that fossil fuel dependence leaves economies, businesses, markets and people at the mercy of each new conflict or trade policy lurch”.

According to the Guardian, he added:

“There is a clear solution to this fossil-fuel cost chaos – renewables are now cheaper, safer and faster-to-market, making them the obvious pathway to energy security and sovereignty.”

UN secretary-general António Guterres said in a statement that renewable energy offers countries an “exit ramp” away from fossil-fuel dependence. He added:

“Homegrown renewable energy has never been cheaper, more accessible or more scalable. The resources of the clean-energy era cannot be blockaded or weaponised. There are no price spikes for sunlight and no embargoes on the wind.

“The fastest path to energy security, economic security and national security is clear: speed up a just transition away from fossil fuels and toward renewable energy.”

Dr Markus Krebber, chief executive at the German energy giant RWE, wrote on LinkedIn that the crisis raised the importance of “fixing the grids”, electrifying “everything that makes sense” and “relentlessly scaling renewables”. He said:

“The imperative of our time: The more we electrify, the less we import fossil fuels. The less we import, the more resilient we become.”

BusinessGreen reported on how the disruption to energy supplies is “pushing up petrol prices – and boosting the case for electric vehicles”, citing analysis of potential costs for UK drivers by the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU).

News outlets have cited Nepal and Ethiopia as examples of countries that rely on fossil-fuel imports, which have taken steps to accelerate the electrification of their road transport.

Some commentators noted that the rhetoric around boosting energy sovereignty through renewables matched narratives seen following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

While European countries have cut their dependence on pipeline gas from Russia, much of that dependence has instead moved to imports of LNG from the US. Prof Jan Rosenow, energy programme lead at the University of Oxford, told a recent briefing for journalists:

“There’s a lot more LNG in the mix. But when you look at the dependency rate of Europe on oil and gas, it hasn’t really gone down. We have diversified, but we haven’t really managed to scale the alternatives fast enough and I think now we pay the price for that.”

Despite this ongoing reliance on fossil fuels, there has been growth in wind and solar capacity both in Europe and elsewhere in recent years. There has also been rapid growth in some developing countries.

Some analysis has pointed to the example of Pakistan, which massively increased its use of solar power amid a surge in LNG prices linked to the war in Ukraine, as a possible model for other countries. This could be particularly appealing for other countries that rely heavily on fossil-fuel imports – and are, therefore, exposed to price spikes.

Isaac Levi, an analyst at the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), told Heatmap News:

“This is the first oil and gas crisis-slash-pricing scare in which clean alternatives to oil and gas are fully price-competitive…Looking at the solar booms, we can expect this to boost clean-energy deployment in a major way, and that will be the more significant and durable impact.”

The solar panels driving such “booms” are cheap imports from China. Some experts have noted how China is well-placed to navigate a new energy crisis. Prof Jason Bordoff and Dr Erica Downs, both from the Center on Global Energy Policy at Columbia University, wrote in Foreign Policy that the Iran war “could consolidate China’s energy dominance”. They wrote:

“Rapidly expanding grids or deploying large volumes of solar, wind and storage is exceedingly difficult without deepening reliance on Chinese firms and materials.”

Tom Ellison, deputy director of the Center for Climate and Security and a former member of the US intelligence community, wrote in Sustainable Views that reliance on the “autonomous electricity production” of wind and solar would be preferable to fossil fuels:

“They do not rely on continuously operating pipelines, ports or shipping lanes that can be switched off, blockaded or hit by a hurricane. There is no Strait of Hormuz or Nord Stream II for clean energy.

“That is not to say clean energy is risk-free. No system is. But the challenges of clean energy, including China’s dominance of key material and mineral supply chains, are more manageable than those of fossil fuels.”

King’s College London researchers writing in the Conversation considered the geopolitics of a similar conflict in a world “powered by renewables, not fossil fuels”. They noted that renewable construction depends on critical minerals, adding:

“While mineral supply chains remain uneven…they do not converge on a single chokepoint.”

Some analysts noted that increases in fossil-fuel prices and the benefits of a cleaner energy system would not necessarily guarantee a surge in low-carbon investment.

Bloomberg cited David Hostert, global head of economics and modeling at BloombergNEF, who explained that higher energy prices could spark inflation, leading to higher interest rates and, therefore, higher costs to deploy clean energy.

According to Morningstar equity analyst Tancrède Fulop, this was part of the reason why the last energy crisis did not lead to a universal surge in renewable capacity. “Renewable companies materially under-performed because of those high interest rates,” he told Climate Home News.

The post Q&A: What does the Iran war mean for the energy transition and climate action? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: What does the Iran war mean for the energy transition and climate action?

Climate Change

The Latest Tactic for Silencing Ecuador’s Environmental Defenders: Shuttering Their Bank Accounts

As the country moves to intensify mining and oil operations, environmental and Indigenous leaders’ bank accounts are being frozen or closed. Such “debanking” cuts them off from financial support and paralyzes their work.

It was a sweltering January afternoon in the Amazonian town of Puyo when Andrés Tapia realized his daughter’s public school fees were due. Like many Ecuadorians, he reached for his phone to make a mobile transfer.

The Latest Tactic for Silencing Ecuador’s Environmental Defenders: Shuttering Their Bank Accounts

Climate Change

Amid Cuts to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Species Like the Florida Panther Languish

Florida conservation groups say they plan to sue after the federal government greenlit another development that threatens the habitat of the panther, the official state animal.

The honey-colored Florida panther inhabits the southwest corner of the state, mostly occupying a remote swath of cypress swamps, sawgrass prairies and other natural and agricultural lands that constitute less than 5 percent of the large feline’s historic range.

Amid Cuts to the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, Species Like the Florida Panther Languish

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits