Keeping global warming to less than 2C above pre-industrial temperatures is “crucial” for limiting damage to the Antarctic Peninsula’s unique ecosystems, according to a new study.

The paper, published in Frontiers in Environmental Science, reviews the latest literature on the impacts of warming on Antarctica’s most biodiverse region.

The Antarctic Peninsula is home to many types of penguins, whales and seals, as well as the continent’s only two flowering plant species.

The study also analyses previously published data and model output to create a fuller picture of the potential futures facing the peninsula under different levels of global warming.

Under a low-emissions scenario that keeps global temperature rise to less than 2C, the Antarctic Peninsula will still face 2.28C of warming by the end of the century, the study says, while higher-emissions futures could push the region’s warming above 5C.

Limiting warming to 2C would avoid the more dramatic impacts associated with higher emissions, such as ice-shelf collapse, increasingly frequent extreme weather events and extinction of some of the peninsula’s native species, according to the paper.

However, warming of 4C would result in “dramatic and irreversible” damages, it adds.

Importantly, the paper shows that the outlook for the peninsula is “dependent on the choices we make now and in the near future”, a researcher not involved in the study tells Carbon Brief.

‘Alternative futures’

The Antarctic Peninsula juts northwards from West Antarctica, stretching towards the tip of South America.

The region is made up of the main peninsula, which spans around 232,000 square kilometres (km2) and a series of islands and archipelagos that cover another 80,000km2. The mainland peninsula is nearly entirely covered in ice, while its islands – many of which are further north – are around 92% covered.

Taken as a whole, the Antarctic Peninsula is the most biodiverse region of the icy continent, and a “beautiful, pristine environment”, says Prof Bethan Davies, a glaciologist at Newcastle University, who led the new work.

It hosts many species of penguins and whales, as well as apex predators, such as orcas and leopard seals. Each spring, more than 100m birds nest there to rear their young. It is also home to hundreds of species of moss and lichens, along with the only two flowering plant species on the continent.

The peninsula is also the part of Antarctica that is undergoing the most significant changes due to climate change, according to the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC’s) sixth assessment report.

In 2019, a group of researchers published a study on the fate of the Antarctic Peninsula at 1.5C of global warming above pre-industrial temperatures. However, it has since “become apparent” that keeping warming below this limit is no longer in reach, Davies says.

The team selected three warming scenarios for their study:

- a low-emissions scenario, SSP1-2.6

- a high-emissions scenario characterised by growing nationalism, SSP3-7.0

- a very-high-emissions scenario, SSP5-8.5

SSP1-2.6 represents the “new goal” of keeping warming less than 2C, Davies says.

SSP3-7.0 and SSP5-8.5 represent “alternative futures” – with the former being one that “felt quite relevant” to the current state of the world and the latter being “useful to consider as a high end”, she adds.

For each potential future, the researchers conducted a literature review to assess the changes to different parts of the peninsula’s physical and biological systems. To fill gaps in the published literature, the team also reanalysed existing datasets and results from the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project 6 (CMIP6) group of models developed for the IPCC’s latest assessment cycle.

Dr Sammie Buzzard, a glaciologist at the Centre for Polar Observation and Modelling, tells Carbon Brief:

“By choosing three different emissions scenarios, they’ve shown just how much variability there is in the possible future of the Antarctica Peninsula that is dependent on the choices we make now and in the near future.”

Buzzard, who was not involved in the new study, adds that it “highlights the consequences of this [change] for the glaciers, sea ice and unique wildlife habitats in this region”.

Physical changes

The Antarctic Peninsula is already experiencing climate change, with one record showing sustained warming over nearly a century. The peninsula is also warming more rapidly than the global average.

For the new study, Davies and her team assess the changes in temperature for the decade 2090-99 across 19 CMIP6 models.

They find that under the low-emissions scenario, the Antarctic Peninsula is projected to warm by 2.28C compared to pre-industrial temperatures, or about 0.55C above its current level of warming. Under the high- and very-high-emissions scenarios, the peninsula will reach temperatures of 5.22C and 6.10C above pre-industrial levels, respectively.

They also analyse output from 12 sea ice models.

In each scenario, they find that the western side of the Antarctic Peninsula experiences the largest declines in sea ice concentration during the winter months of June, July and August. For the southern hemisphere’s summertime, it is the eastern side of the peninsula that shows the largest decreases.

The maps below show the projected change in sea-ice concentration around the Antarctic Peninsula for each season (left to right) under low (top), high (middle) and very high (bottom) emissions. Decreasing concentrations are shown in blue and increasing concentrations are shown in red.

The paper gives a “great overview of the current literature on the Antarctic Peninsula, examining multiple aspects of the region holistically”, Dr Tri Datta, a climate scientist at the Delft University of Technology, tells Carbon Brief.

However, Datta – who was not involved in the study – notes that the coarse resolution of CMIP6 models means that the “most vulnerable regions are too poorly represented to capture important feedbacks”, such as the forming of meltwater ponds on the tops of glaciers, which warm much more than the icy surface around them.

Ecosystem impacts

The study also looks at potential futures for the Antarctic Peninsula’s marine and terrestrial ecosystems – albeit, much more briefly than it examines the physical changes.

This is because modelling ecosystem change is very difficult, Davies explains:

“If you’re going to model an ecosystem, you have to model the climate and the ocean and the ice and how that changes. Exactly how that ecosystem responds to those changes is still beyond most of our Earth system models.”

Still, by looking at trends in the Antarctic over the past several decades, as well as changes that have occurred in other high-latitude regions, the researchers piece together some of the potential impacts of warming.

They conclude that under SSP1, the changes experienced by ecosystems are “uncertain”, but will “likely” be similar to present day – with some terrestrial species, such as its flowering plants, even benefitting from increased habitat area and water availability.

However, under higher-emissions scenarios, species will become “increasingly likely” to experience warmer temperatures than they are suited for.

Other changes that may occur in the very-high-emissions scenario are closely linked to the projected reductions in sea ice. These include the increased spread of invasive alien species, reduced ranges for krill and the displacement of animals unable to tolerate the warmer temperatures by those more able to adapt.

Prof Scott Doney, an oceanographer and biogeochemist at the University of Virginia, notes that some of these changes are already happening. Doney, who was not involved in the study, is part of an ongoing research programme on the Antarctic Peninsula known as the Palmer Long-Term Ecological Research project.

He tells Carbon Brief that Adélie penguins, which are a polar species, have “seen a massive drop in their breeding population” at their research sites. Meanwhile, gentoo penguins – whose range extends into the subpolar regions – “have been quite opportunistic” in colonising those breeding sites.

‘Changes here first’

Antarctica is home to 50 year-round research stations and dozens of summer-only ones, operated by more than 30 countries.

Around a dozen year-round stations are found on the peninsula and its islands, including the oldest permanent settlement in Antarctica – Argentina’s Base Orcadas, established in 1903 by the Scottish national Antarctic expedition.

The continent is home to commercially important fisheries – particularly krill, which also play a critical role in the Antarctic marine food chain.

Increasingly, the Antarctic Peninsula is also a tourist destination.

Climate change poses a threat to all of these activities, Davies says.

For example, much of the research infrastructure on the Antarctic Peninsula was “built to assume dry, snowy conditions”, she says. Rain can “cause quite a lot of difficulty”, she adds.

(In an article published last year, Carbon Brief looked at the causes of rain in sub-zero temperatures in West Antarctica.)

Decreased sea ice cover can impact krill populations. It can also lead to increased ship traffic, as more of the continent becomes accessible throughout more of the year.

Furthermore, Davies says, the changes occurring on the peninsula will reverberate across Antarctica and around the world. She tells Carbon Brief:

“We’ll see changes here first and those changes will continue to be felt in West Antarctica and continent-wide…What happens in Antarctica doesn’t stay in Antarctica.”

The post Limiting warming to 2C is ‘crucial’ to protect pristine Antarctic Peninsula appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Limiting warming to 2C is ‘crucial’ to protect pristine Antarctic Peninsula

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 20 February 2026: EU’s ‘3C’ warning | Endangerment repeal’s impact on US emissions | ‘Tree invasion’ fuelled South America’s fires

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Preparing for 3C

NEW ALERT: The EU’s climate advisory board urged countries to prepare for 3C of global warming, reported the Guardian. The outlet quoted Maarten van Aalst, a member of the advisory board, saying that adapting to this future is a “daunting task, but, at the same time, quite a doable task”. The board recommended the creation of “climate risk assessments and investments in protective measures”.

‘INSUFFICIENT’ ACTION: EFE Verde added that the advisory board said that the EU’s adaptation efforts were so far “insufficient, fragmented and reactive” and “belated”. Climate impacts are expected to weaken the bloc’s productivity, put pressure on public budgets and increase security risks, it added.

UNDERWATER: Meanwhile, France faced “unprecedented” flooding this week, reported Le Monde. The flooding has inundated houses, streets and fields and forced the evacuation of around 2,000 people, according to the outlet. The Guardian quoted Monique Barbut, minister for the ecological transition, saying: “People who follow climate issues have been warning us for a long time that events like this will happen more often…In fact, tomorrow has arrived.”

IEA ‘erases’ climate

MISSING PRIORITY: The US has “succeeded” in removing climate change from the main priorities of the International Energy Agency (IEA) during a “tense ministerial meeting” in Paris, reported Politico. It noted that climate change is not listed among the agency’s priorities in the “chair’s summary” released at the end of the two-day summit.

US INTERVENTION: Bloomberg said the meeting marked the first time in nine years the IEA failed to release a communique setting out a unified position on issues – opting instead for the chair’s summary. This came after US energy secretary Chris Wright gave the organisation a one-year deadline to “scrap its support of goals to reduce energy emissions to net-zero” – or risk losing the US as a member, according to Reuters.

Around the world

- ISLAND OBJECTION: The US is pressuring Vanuatu to withdraw a draft resolution supporting an International Court of Justice ruling on climate change, according to Al Jazeera.

- GREENLAND HEAT: The Associated Press reported that Greenland’s capital Nuuk had its hottest January since records began 109 years ago.

- CHINA PRIORITIES: China’s Energy Administration set out its five energy priorities for 2026-2030, including developing a renewable energy plan, said International Energy Net.

- AMAZON REPRIEVE: Deforestation in the Brazilian Amazon has continued to fall into early 2026, extending a downward trend, according to the latest satellite data covered by Mongabay.

- GEZANI DESTRUCTION: Reuters reported the aftermath of the Gezani cyclone, which ripped through Madagascar last week, leaving 59 dead and more than 16,000 displaced people.

20cm

The average rise in global sea levels since 1901, according to a Carbon Brief guest post on the challenges in projecting future rises.

Latest climate research

- Wildfire smoke poses negative impacts on organisms and ecosystems, such as health impacts on air-breathing animals, changes in forests’ carbon storage and coral mortality | Global Ecology and Conservation

- As climate change warms Antarctica throughout the century, the Weddell Sea could see the growth of species such as krill and fish and remain habitable for Emperor penguins | Nature Climate Change

- About 97% of South American lakes have recorded “significant warming” over the past four decades and are expected to experience rising temperatures and more frequent heatwaves | Climatic Change

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

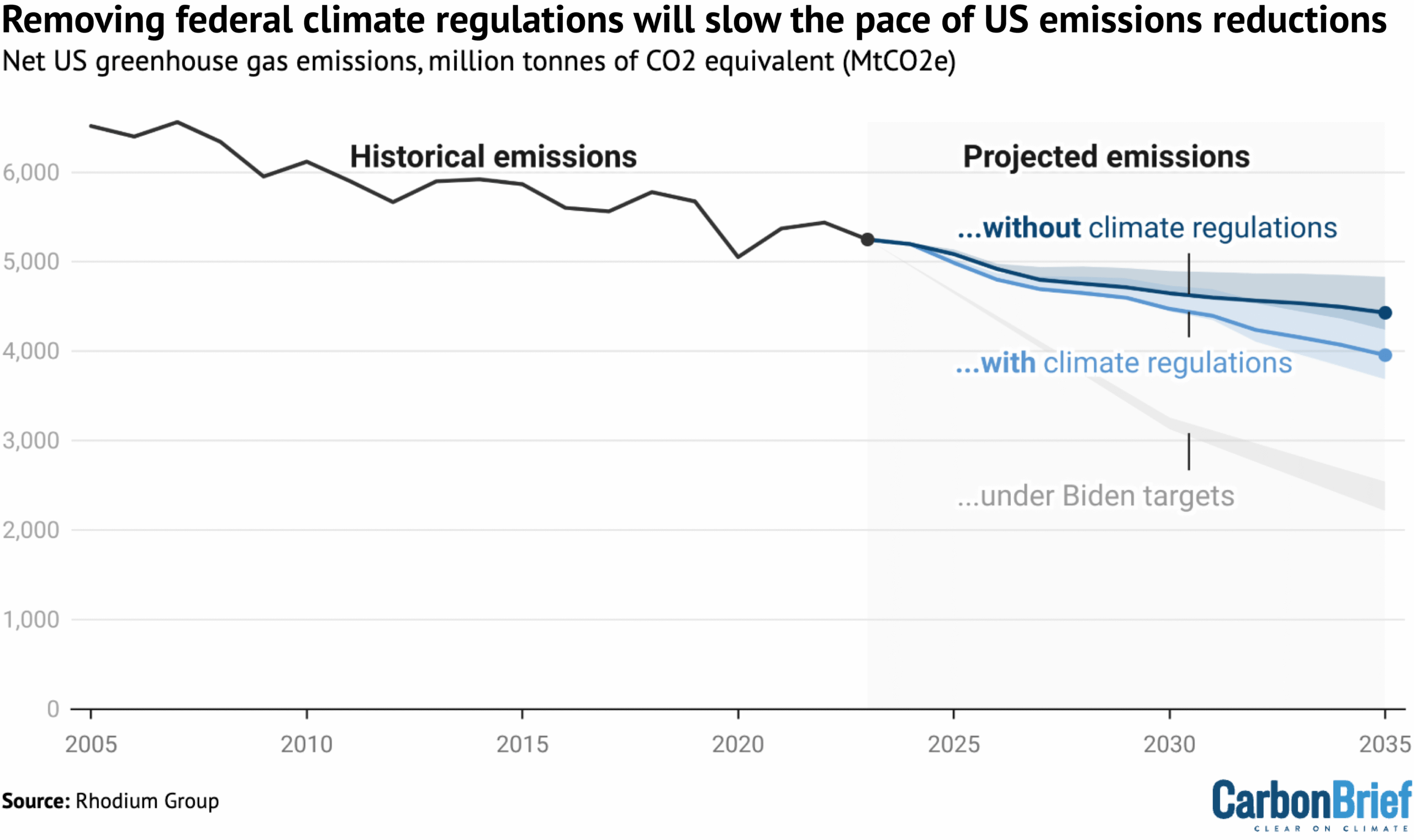

Repealing the US’s landmark “endangerment finding”, along with actions that rely on that finding, will slow the pace of US emissions cuts, according to Rhodium Group visualised by Carbon Brief. US president Donald Trump last week formally repealed the scientific finding that underpins federal regulations on greenhouse gas emissions, although the move is likely to face legal challenges. Data from the Rhodium Group, an independent research firm, shows that US emissions will drop more slowly without climate regulations. However, even with climate regulations, emissions are expected to drop much slower under Trump than under the previous Joe Biden administration, according to the analysis.

Spotlight

How a ‘tree invasion’ helped to fuel South America’s fires

This week, Carbon Brief explores how the “invasion” of non-native tree species helped to fan the flames of forest fires in Argentina and Chile earlier this year.

Since early January, Chile and Argentina have faced large-scale and deadly wildfires, including in Patagonia, which spans both countries.

These fires have been described as “some of the most significant and damaging in the region”, according to a World Weather Attribution (WWA) analysis covered by Carbon Brief.

In both countries, the fires destroyed vast areas of native forests and grasslands, displacing thousands of people. In Chile, the fires resulted in 23 deaths.

Multiple drivers contributed to the spread of the fires, including extended periods of high temperatures, low rainfall and abundant dry vegetation.

The WWA analysis concluded that human-caused climate change made these weather conditions at least three times more likely.

According to the researchers, another contributing factor was the invasion of non-native trees in the regions where the fires occurred.

The risk of non-native forests

In Argentina, the wildfires began on 6 January and persisted until the first week of February. They hit the city of Puerto Patriada and the Los Alerces and Lago Puelo national parks, in the Chubut province, as well as nearby regions.

In these areas, more than 45,000 hectares of native forests – such as Patagonian alerce tree, myrtle, coigüe and ñire – along with scrubland and grasslands, were consumed by the flames, according to the WWA study.

In Chile, forest fires occurred from 17 to 19 January in the Biobío, Ñuble and Araucanía regions.

The fires destroyed more than 40,000 hectares of forest and more than 20,000 hectares of non-native forest plantations, including eucalyptus and Monterey pine.

Dr Javier Grosfeld, a researcher at Argentina’s National Scientific and Technical Research Council (CONICET) in northern Patagonia, told Carbon Brief that these species, introduced to Patagonia for production purposes in the late 20th century, grow quickly and are highly flammable.

Because of this, their presence played a role in helping the fires to spread more quickly and grow larger.

However, that is no reason to “demonise” them, he stressed.

Forest management

For Grosfeld, the problem in northern Patagonia, Argentina, is a significant deficit in the management of forests and forest plantations.

This management should include pruning branches from their base and controlling the spread of non-native species, he added.

A similar situation is happening in Chile, where management of pine and eucalyptus plantations is not regulated. This means there are no “firebreaks” – gaps in vegetation – in place to prevent fire spread, Dr Gabriela Azócar, a researcher at the University of Chile’s Centre for Climate and Resilience Research (CR2), told Carbon Brief.

She noted that, although Mapuche Indigenous communities in central-south Chile are knowledgeable about native species and manage their forests, their insight and participation are not recognised in the country’s fire management and prevention policies.

Grosfeld stated:

“We are seeing the transformation of the Patagonian landscape from forest to scrubland in recent years. There is a lack of preventive forestry measures, as well as prevention and evacuation plans.”

Watch, read, listen

FUTURE FURNACE: A Guardian video explored the “unbearable experience of walking in a heatwave in the future”.

THE FUN SIDE: A Channel 4 News video covered a new wave of climate comedians who are using digital platforms such as TikTok to entertain and raise awareness.

ICE SECRETS: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast explored how scientists study ice cores to understand what the climate was like in ancient times and how to use them to inform climate projections.

Coming up

- 22-27 February: Ocean Sciences Meeting, Glasgow

- 24-26 February: Methane Mitigation Europe Summit 2026, Amsterdam, Netherlands

- 25-27 February: World Sustainable Development Summit 2026, New Delhi, India

Pick of the jobs

- The Climate Reality Project, digital specialist | Salary: $60,000-$61,200. Location: Washington DC

- Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), science officer in the IPCC Working Group I Technical Support Unit | Salary: Unknown. Location: Gif-sur-Yvette, France

- Energy Transition Partnership, programme management intern | Salary: Unknown. Location: Bangkok, Thailand

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 20 February 2026: EU’s ‘3C’ warning | Endangerment repeal’s impact on US emissions | ‘Tree invasion’ fuelled South America’s fires appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Q&A: How Trump is threatening climate science in Earth’s polar regions

Since Donald Trump returned to the White House last year, his administration in the US has laid off thousands of scientists and frozen research grants worth billions of dollars.

The cutbacks have had far-reaching consequences for all areas of scientific research, extending all the way to Earth’s fragile polar regions, researchers say.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, polar researchers explain how Trump’s attacks on science have affected efforts to study climate change at Earth’s poles, including by disrupting fieldwork, preventing data collection and even forcing researchers to leave the US.

One climate scientist tells Carbon Brief that the administration’s decision to terminate the only US icebreaker used in Antarctica forced her to cancel her fieldwork at the last minute – with her scientific cargo still held up in Chile.

As US polar scientists reel from the cuts, Trump has caused a geopolitical storm with threats to take control of Greenland, the self-ruling island which is part of the Kingdom of Denmark and located between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans.

Below, Carbon Brief speaks to experts about what Trump’s sweeping changes could mean for climate science at Earth’s poles

- Why is the US important for polar research?

- How has Trump affected US polar research in his second term?

- What could the changes mean for international climate research at Earth’s poles?

- What could be the impact of Trump’s threats to take control of Greenland on climate research?

Why is the US important for polar research?

The US’s wealth, power and geography have made it a key player in polar research for more than a century.

Ahead of Trump’s second term, the National Science Foundation (NSF), a federal agency that funds US science, was the largest single funder of polar research globally, with its Office of Polar Programs overseeing extensive research in both the Arctic and Antarctica.

The US has three permanent bases in Antarctica: McMurdo Station, Amundsen-Scott South Pole Station and Palmer Station.

In Alaska, which the US purchased from Russia in 1867, there is the Toolik Field Station and the Barrow Arctic Research Center. The US also has the Summit Station in Greenland.

US institutes operate several satellites that provide scientists across the world with key data on the polar regions.

This includes the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s (NOAA) Joint Polar Satellite System, which provides data used for extreme weather forecasting.

Over the past few years, US institutes have led and provided support for the world’s largest polar expeditions.

This includes MOSAiC, the largest Arctic expedition on record, which took place from 2019-20 and was co-led by research institutes from the US and Germany. [Carbon Brief joined the expedition for its first leg and covered it in depth with a series of articles.]

The US has historically been “incredibly valuable” to research efforts in the Arctic and Antarctica, a senior US polar scientist currently living in Europe, who did not wish to be named, tells Carbon Brief.

“For a lot of the international collaborations, the US is a big component, if not the largest,” the scientist says.

“We do a lot of collaborative work with other countries,” adds Dr Jessie Creamean, an atmospheric scientist working in polar regions based at Colorado State University. “Doing work in the polar regions is really an international thing.”

How has Trump affected US polar research in his second term?

Since returning to office, the Trump administration has frozen or terminated 7,800 research grants from federal science agencies and laid off 25,000 scientists and personnel.

This includes nearly 2,000 research grants from the NSF, which is responsible for the Office for Polar Programs and for funding a broad range of climate and polar research.

Courts have since made orders to reinstate thousands of these grants and some universities have settled with the federal government to unfreeze funding. However, it is unclear whether scientists have yet received those funds.

As with other areas of US science, the impact of Trump’s attacks on polar research have been far-reaching and difficult to quantify, scientists tell Carbon Brief.

Key scientific institutions affected include NASA, NOAA and the National Center for Atmospheric Research (NCAR) in Colorado.

In December, the Trump administration signalled that it planned to dismantle NCAR, calling it a source of “climate alarmism”. At the end of January, the NSF published a letter that “doubled down” on the administration’s promise to “restructure” and “privatise” NCAR.

NCAR has been responsible for a host of polar research in recent years, with several NCAR scientists involved in the MOSAiC expedition.

“NCAR is kind of like a Mecca for atmospheric research,” the US polar scientist who did not want to be named tells Carbon Brief. “They’ve done so much. Now their funding is drying up and people are scrambling.”

At NOAA, one of the major polar programmes to be affected is the National Snow and Ice Data Center (NSIDC), which regularly issues updates about Arctic and Antarctic sea ice.

Last July, Space reported that researchers at NSIDC were informed by the Department of Defense – now renamed the Department of War under Trump – that they would lose access to data from a satellite operated by the US air force, which was used to calculate sea ice changes.

Although the Department of Defense reversed the decision following a public outcry, the uncertainty drove the researchers at NSIDC to switch to sourcing data from a Japanese satellite instead, explains Dr Zack Labe. Labe is a climate scientist who saw his position at NOAA terminated under the Trump administration and now works at the nonprofit research group Climate Central. He tells Carbon Brief:

“It looked like they were losing access to that data and, after public outcry, they regained access to the data. And then, later this year, they had to switch to another satellite.”

He adds that the Trump administration’s layoffs and budget cuts has also forced the programme to scale back its communications initiatives:

“A big loss at NSIDC is that they used to put out these monthly summaries of current conditions in Greenland, the Arctic and Antarctic called Sea Ice Today. It was a really important resource to describe the current weather and sea ice conditions in these regions.

“These reports went to stakeholders, they went to Indigenous communities within the Arctic. And that has stopped in the past year due to budget cuts.”

Elsewhere, the New York Times reported that a director at the Office for Polar Programs found out she was being laid off while on a trip to Antarctica.

US polar research took another hit in September, when the NSF announced that it was terminating the lease for the Nathaniel B Palmer, the only US icebreaker dedicated to Antarctic research.

The statement gave just one month’s notice, saying that the vessel would be returned to its operator in October.

Creamean was among the scientists who were affected by the termination. She tells Carbon Brief:

“I was supposed to go on that icebreaker in September. I have a project funded at Palmer Station, along with colleagues from Scripps Institution of Oceanography. We were supposed to go set up for an 18-month study there. We have the money for the project, but we just didn’t get to go because the icebreaker got decommissioned.

“It was a big bummer. We shipped everything down to South America. All of our cargo is still sitting in Punta Arenas [in Chile].”

Elsewhere, other scientists have warned that the termination of the icebreaker could affect the continuity of Antarctic data collection.

In a statement, Dr Naomi Ochwat, a glaciologist at the University of Colorado, Boulder, said that decades of data on changes to Antarctic glaciers taken from the deck of the Palmer had been vital to her research.

For some, one of the most worrying impacts of Trump’s attacks on US polar science is on the careers of scientists, which will likely lead to many of them leaving the country.

All of the researchers that Carbon Brief spoke to said they had heard many stories of US polar scientists deciding to relocate outside of the country or to leave the profession altogether.

Creamean is one of the polar scientists to make the difficult decision to temporarily leave the US. She says:

“I’m actually moving to Sweden for a year starting in May. I’m going to do a visiting science position [at Stockholm University]. I’m hoping to come back. But if things are not looking good and things are looking more positive in Sweden, maybe I’ll stay there. I don’t know.”

Labe tells Carbon Brief that the “brain drain” of US scientists is the “biggest story” when it comes to Trump’s impact on polar research:

“I think one of the long-term repercussions is just how many people will be forced out of science due to a lack of opportunities. I think this is something that will grow in 2026. There were a lot of grants that were two-to-three years and, so, were still running, but they will be ending now.”

What could the changes mean for international climate research at Earth’s poles?

With all research at Earth’s poles relying heavily on international collaboration, Trump’s attacks on science are likely to have far-reaching implications outside of the US, scientists tell Carbon Brief.

One implication of budget and personnel cuts could be the loss of continuous data from US researchers, bases and satellites.

Many US polar datasets have been collected for decades and are relied upon by scientists and institutes around the world. This includes records for Arctic and Antarctica’s oceans, sea ice, atmosphere and wildlife.

Trump’s impact has highlighted to scientific organisations outside of the US how vulnerable US datasets can be to political changes, says Labe, adding:

“From a climate perspective, you need a consistent data record over a long period of time. Even a small gap in data caused by uncertainty can cause major issues in understanding long-term trends in the polar regions.

“Other scientific organisations around the world are realising that they’re going to have to find alternative sources for data.”

Creamean tells Carbon Brief that, while some datasets have been discontinued, researchers have made an effort to keep records going despite personnel and budget constraints. She says:

“I know at Summit Station in Greenland they had some instruments that were pulled out that had been measuring things like the surface energy budget for a long time. That dataset has been discontinued.

“Thankfully, some programmes have been able to somehow hold on and continue to do baseline measurements. There’s a station up in Alaska [Barrow] where, as far as I know, measurements have been maintained there. That’s good because some measurements up there have been happening since the 60s and 70s.”

Trump’s changes could also cast uncertainty over the US’s role in taking part and offering support to upcoming collaborative Arctic and Antarctic expeditions.

In addition to helping scientists better understand the impact of climate change on Earth’s polar regions, these expeditions have also enabled countries with testy geopolitical relationships to come together for a common goal, the US polar scientist who did not want to be named tells Carbon Brief.

For example, the MOSAiC expedition from 2019-20 saw the US and Germany work alongside Russian and Chinese research institutes to study the impact of climate change on the Arctic, says the scientist, adding:

“It was an international collaboration that involved people who should be geopolitical enemies. Science is a way that we seem to be able to work together, to solve problems together, because we all live on one planet. And, right now, to see these changes in the US, it’s quite concerning [for these kinds of collaborations].”

The retreat of the US from polar research might see other powers step up to fill the gap, scientists tell Carbon Brief.

Several scientists mentioned the Nordic countries as possibly taking a larger role in leading polar research, while one said that “China seems to be picking up the slack that’s left behind”.

China currently has five Antarctic research stations – Great Wall, Zhongshan, Kunlun, Taishan and Qinling – along with one Arctic station in Ny-Ålesund, Svalbard.

The Financial Times recently reported on China’s growing ambitions for Arctic exploration, involving its fleet of five icebreakers.

What could be the impact of Trump’s threats to take control of Greenland on climate research?

In recent months, Trump has whipped up a media frenzy with threats to take control of Greenland, the world’s largest island lying between the Arctic and Atlantic oceans, which is self-governing and part of the Kingdom of Denmark.

Last month, he clarified that he will not try to take Greenland “by force”, but that he is seeking “immediate negotiations” to acquire the island for “national security reasons”.

Trump’s interest in the island is likely influenced by the rapid melting away of Arctic sea ice due to climate change, which is opening up new sea routes and avenues for potential resource exploitation, reported the Washington Post.

His comments have sparked condemnation from a wide range of US scientists who conduct fieldwork in Greenland.

An open letter signed by more than 350 scientists “vehemently opposes” Trump’s threats to take control of Greenland and expresses “solidarity and gratitude” to Greenland’s population. It says:

“Greenland deserves the world’s attention: it occupies a key position geopolitically and geophysically. As climate warms, rapid loss of Greenland’s ice affects coastal cities and communities worldwide.”

A breakdown in diplomatic relations between the US and Greenland could prevent scientists from being able to carry out their climate research on the island, one of the scientists to sign the letter wrote in a supporting statement:

“Scientific access to Arctic environments is essential for research which secures our shared future and, directly, materially benefits American citizens. It is deeply upsetting that these essential relationships are being undermined, perhaps irreparably, by the Trump administration.”

Dr Yarrow Axford, one of the letter’s organisers who is a palaeoclimatologist and science communicator based in Massachusetts, told Nature that Trump’s comments could put Greenland climate research at risk, saying:

“We Americans have benefited from all these decades of peaceful partnership with Greenland. Scientific understanding of climate change has benefited tremendously. I hope scientists can reach out to Congress and point out what a wonderful partnership that is.”

In addition to the US-run Summit Station, there are at least eight other research stations in Greenland, operated by a range of institutions from across the world.

A major focus of research efforts in the region is the Greenland ice sheet, Earth’s second-largest body of ice which is rapidly melting away because of climate change.

The ice sheet holds enough freshwater to raise global sea levels by around more than seven metres, if melted completely.

Any political moves that could “jeopardise” the study of the Greenland ice sheet would be detrimental, says Creamean:

“Greenland is a ‘tipping point’ in that, the ice sheet melting, that could be one of the biggest contributors to sea level rise. It’s not like we can wait to study it, it needs to be understood now.”

The post Q&A: How Trump is threatening climate science in Earth’s polar regions appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: How Trump is threatening climate science in Earth’s polar regions

Greenhouse Gases

China Briefing 19 February 2026: CO2 emissions ‘flat or falling’ | First tariff lifted | Ma Jun on carbon data

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s China Briefing.

China Briefing handpicks and explains the most important climate and energy stories from China over the past fortnight. Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Carbon emissions on the decline

‘FLAT OR FALLING’: China’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions have been either “flat or falling” for almost two years, reported Agence France-Presse in coverage of new analysis for Carbon Brief by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA). This marks the “first time” annual emissions may have fallen at a “time when energy demand was rising”, it added. Emissions fell 0.3% during the year, driven by a fall in emissions “across nearly all major sectors”, said Bloomberg – including the power sector. It said the chemicals sector was an exception, where emissions saw a “large jump from a surge of new plants using coal and oil” as feedstocks. The analysis has been covered around the world by outlets ranging from the New York Times, Bloomberg and BBC News through to Der Spiegel, CGTN and the Guardian.

TOP TASKS: President Xi Jinping listed “persisting in following the ‘dual-carbon’ goals” as one of eight “key” elements of economic work in 2026, according to a December speech just published in Qiushi, the Chinese Communist party’s leading journal for political theory. This included “deeply advancing” carbon reduction in key industries and “steadily promoting a peak in consumption of coal and oil”, according to the transcript. The National Energy Administration (NEA) also outlined a number of priority tasks for the department, including resolving “grid integration challenges” to encourage greater use of renewable energy and “boosting investment” in energy resources, said energy news outlet International Energy Net.

ETS EXPANSION: Meanwhile, the government has asked “heavy polluters” in several sectors not yet covered in China’s emissions trading scheme (ETS) to report their emissions for 2025, reported Bloomberg, in a “key step” for the further expansion of the carbon market. The affected industries are the “petrochemical, chemical, building materials (flat glass), nonferrous metals (copper smelting), paper and civil aviation industries”, according to the original notice posted by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE), as well as steel and cement companies not yet covered by the ETS.

State Council issued ‘unified’ power market guidance

POWER TRADE: China will aim for “market-based transactions” to account for 70% of total electricity consumption by 2030, according to new policy guidance released by China’s State Council and published by International Energy Net. The policy also called for greater “integration” of cross-regional trading and “fundamentally sound” market-based pricing mechanisms. On renewable power, the guidance urged officials to “expand the scale of green power consumption” and establish a “green certificate consumption system that combines mandatory and voluntary consumption”, as well as encourage “implementation of inter-provincial renewable energy priority dispatch plans”. It also calls for “roll[ing] out spot trade nationwide by 2027, up from just 4% of the total transactions today”, reported Bloomberg.

CLEAN-POWER PUSH: An official at China’s National Development and Reform Commission said in a Q&A published by BJX News that establishing a “unified” national power market is “crucial for constructing a new power system”. A separate analysis by Beijing-based power services firm Lambda reposted on BJX News argues that China’s unified power-market reforms – which have been “more than two decades” in the making – will allow for “widespread integration” of renewable energy, resolving the challenge of wind and solar “generating but being unable to transmit and integrate”. Business news outlet Jiemian quoted Xiamen University professor Lin Boqiang saying that, while power-market reform may present clean-energy companies with “growing pains” in the short term, it will “force the industry to develop healthily” in the long term.

EU tariffs lifted on first firm’s China-built EV imports

‘SOFTENED’ STANCE: The Chinese government has “softened its stance” on electric vehicle (EV) manufacturers who seek to independently negotiate with the EU on prices for their exports to the bloc, said Reuters, after it previously “urged the bloc not to engage in separate talks with Chinese manufacturers”. The move came as Volkswagen received an exemption from tariffs for one of its EVs that is made in China and imported to the EU, which it committed to sell above a specific price threshold, reported Bloomberg. It added that the company also pledged to follow an import quota and “invest in significant battery EV-related projects” in the EU.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “China Briefing” email newsletter. All you need to know about the latest developments relating to China and climate change. Sent to your inbox every Thursday.

‘MADE IN EU’ MELTDOWN: Meanwhile, EU policymakers attempted to agree legislation that may force EV manufacturers to ensure “70% of the components in their cars are made in the EU” if they wish to receive subsidies, reported the Financial Times. A draft of the plan was ultimately rejected by nine European Commission leaders and commission president Ursula von der Leyen, Borderlex managing editor Rob Francis wrote on Bluesky.

BRAZIL BACKTRACKS: Brazil has “scrapped” a tariff exemption for Chinese EV manufacturers that allowed cars assembled in Brazil with parts imported from China to be sold at much lower prices than similar vehicles made from parts imported from other countries, reported the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post. Separately, Bloomberg reported on the surge of tariff-free Chinese EVs that has enabled Ethiopia to ban the import of combustion-engine cars.

PRICE-WAR BAN: The Chinese government has “banned carmakers from pricing vehicles below cost”, reported Bloomberg, in an effort to clamp down on a “persistent price war” affecting the industry. China’s car industry, “particularly in the EV segment”, has seen “aggressive discounting, subsidies and bundled promotions” pushing down profitability for companies across the supply chain, said the state-run newspaper China Daily.

More China news

- POWERFUL WIND: China has connected a 20-megawatt offshore wind turbine – the “world’s most powerful” and “equivalent to a 58-story building” – to the grid, reported state news agency Xinhua.

- PROVINCIAL MOVES: Anhui has become the first Chinese province to release data on how much carbon different forms of power in the province emits per kilowatt-hour of power, according to power news outlet BJX News.

- RARE-EARTH RUNES: China may hold a “policy briefing” on export restrictions for rare earths and other critical minerals in March, according to Reuters.

- NO CHINA CREDITS: The US confirmed that clean-energy tax credits will not be available for companies that are “overly reliant on Chinese-made equipment”, said Reuters.

Spotlight

Ma Jun: ‘No business interest’ in Chinese coal power due to cheaper renewables

Carbon Brief spoke with Ma Jun, one of China’s most well-known environmentalists, about how open data can keep pressure on industry to decarbonise and boost interest in climate change.

Ma is director of the Beijing-based Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE), an organisation most well known for developing the Blue Map, China’s first public database for environment data.

Speaking to Carbon Brief during the first week of COP30 in Brazil last November, the discussion covered the importance of open data, key challenges for decarbonising industry, China’s climate commitments for 2035, cooperation with the EU and more.

Below are highlights from the conversation. The full interview can be found on the Carbon Brief website.

Open data is helping strengthen climate policy

- On how data transparency prevents environmental pollution in China: “From that moment [when the general public began flagging environmental violations on social media in 2014], it was no longer easy for mayors or [party] secretaries to try to interfere with the enforcement, because it’s being made so transparent, so public.”

- On encouraging the Chinese government to publish data: “The ministry felt that they had the backing from the people, basically, which helped them to gain confidence that data can be helpful and can be used in a responsible way.”

- On China’s new corporate disclosure rules: “We’re talking about what’s probably the largest scale of corporate measuring and disclosure now happening [anywhere in the world].”

- On the need for better emissions data: “It will be impossible to get started without proper, more comprehensive measuring and disclosure, and without having more credible data available.”

‘Green premium’ still challenging despite falling prices

- On the economics of coal: “There’s no business interest for the coal sector to carry on, because increasingly the market will trend towards using renewables, because it’s getting cheaper and cheaper”.

- On paying for low-carbon products: “When we engage with them and ask why they didn’t expand production, they say that producing these items will have a ‘green premium’, but no one wants to pay for that. Their users only want to buy tiny volumes for their sustainability reports.”

- On public perceptions in China of climate change: “It’s more abstract – [we’re talking about] the end of the century or the polar bears. People don’t feel that it’s linked with their own individual behaviour or consumption choices.”

Climate cooperation in a new era

- On criticism of China’s climate pledge: “In the west, the cultural tendency is that if you want to show that you’re serious, you need to set an ambitious target. Even if, at the end of the day, you fail, it doesn’t mean that you’re bad…But in China, the culture is that it is embarrassing if you set a target and you fail to fully honour that commitment.”

- On global climate cooperation: “The starting point could be transparency – that could be one of the ways to help bridge the gap.”

The role of civil society in China’s climate efforts

- On working in China as a climate NGO: “What we’re doing is based on these principles of transparency, the right to know. It’s based on the participation of the public. It’s based on the rule of law. We cherish that and we still have the space to work [on these issues].”

- On the climate consensus in China: “The environment – including climate – is the area with the biggest consensus view in [China]. It could be a test run for having more multi-stakeholder governance in our country.”

This interview was conducted by Anika Patel at COP30 in Belém on 13 November 2025.

Watch, read, listen

GREEN ALUMINIUM: Lantau Group principal David Fishman wrote on LinkedIn about why China’s aluminium smelters are seeking greater access to low-carbon power, following heated debate over a Financial Times article.

STRONGER THAN EVER: Isabel Hilton, chair of the Great Britain-China Centre, spoke on the Living on Earth podcast about China’s renewables push and exports of clean-energy technologies.

CUTTING CORNERS?: Business news outlet Caixin examined how a surge in turbine defects at one wind farm could be due to “aggressive cost-cutting and rapid installation waves”.

POLES APART: BBC News’ Global News Podcast examined the drivers behind China’s flatlining emissions, as revealed by Carbon Brief.

600

In gigawatts, China’s total capacity of coal plants that are “flexible” and – in theory – better able to balance the variability of renewables, according to a new report by the thinktank Ember.

New science

- China will see a 41% decline in in coal-mining jobs over the next decade under current climate policies | Environmental Research Letters

- During 2000-20, China’s per-person emissions of CO2 increased from 106kg to 539kg in urban households and from 35kg to 202kg in rural households, indicating that the inequality between urban and rural households is shrinking | Scientific Reports

Recently published on WeChat

China Briefing is written by Anika Patel and edited by Simon Evans. Please send tips and feedback to china@carbonbrief.org

The post China Briefing 19 February 2026: CO2 emissions ‘flat or falling’ | First tariff lifted | Ma Jun on carbon data appeared first on Carbon Brief.

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits