Neat rows of new houses with solar panels on their turquoise roofs radiate out from the quiet central square of Aghali, a government-branded “smart village” in south-western Azerbaijan. A path lined with yellow bushes leads to the river, where a state-of-the-art hydropower plant produces clean electricity for residents.

Aghali is a pioneering example of Azerbaijan’s plan for “green” reconstruction of the territories it captured after a long, bloody conflict with Armenia, centred on the disputed Nagorno-Karabakh mountainous enclave.

Hundreds of Azeris displaced from the region in the early 1990s have moved back to Aghali, a local government official told Climate Home.

“The emotional link to these territories is very strong even though 30 years have passed,” the official said. “Our people are happy to be back”.

The government says more than 100,000 Azeris will return to populate the 30 or so new towns and villages planned across the area by 2026, which are expected to run mainly on clean energy and aim for “net zero” emissions.

Yet a more troubled story lies beneath the shiny surface presented by the authorities – part of Azerbaijan’s efforts to polish its green credentials before the COP29 UN climate summit it will host in November.

Some 136,000 ethnic Armenians who had called Nagorno-Karabakh their homeland fled in a mass exodus during a two-part military offensive by Azerbaijan that started in 2020 and ended last autumn.

For Armenian authorities and some human rights and legal experts, the drive amounted to “ethnic cleansing” – a phrase used in a European Parliament resolution on the conflict. A spokesperson for COP29 told Climate Home the Azerbaijan authorities “categorically reject this view”.

With the fighting now over, the two sides are engaged in talks to build a lasting peace. They struck an initial agreement to establish border demarcations in April, but hopes of a swift breakthrough on a permanent solution remain slim.

Meanwhile, displaced Armenians have said publicly they fear the heritage sites and homes they hastily left behind will be erased under a giant construction effort. Evidence of this was seen last month by Climate Home on a press trip organised and sponsored by the COP29 Presidency team, which controlled access to locations and sources in the region.

‘Net zero’ vision

Azerbaijan has built its prowess, both on and off the battlefield, on the strength of its vast oil and gas reserves. Around 60 percent of the government’s budget is financed through the sale of fossil fuels, primarily via export to Europe.

Last month, Azerbaijan President Ilham Aliyev called oil and gas “a gift from God” at the Petersberg Climate Dialogue in Berlin, signalling continued investment in increased gas production. That is despite signing up, like all countries, to a global agreement to transition away from fossil fuels “in keeping with the science” at the COP28 UN climate summit in Dubai last December.

Nonetheless, as its capital Baku gears up to host COP29, Azerbaijan also wants to show off its efforts to adopt clean energy and cut planet-heating emissions to the outside world.

Nagorno-Karabakh, and the surrounding provinces, lie at the centre of this push. The government has declared a “green energy zone” here, adding a dozen hydropower plants, and seeking to attract foreign investment in solar and wind.

Azerbaijan President Ilham Aliyev in front of a screw turbine hydro power plant in Zangilan, one of the territories recaptured in 2020. Photo: Azerbaijan Presidency

Across the country, the government wants renewables to make up 30 percent of its installed electricity capacity by 2030 – up from 7 percent in 2023. The main motivation is to reduce the use of gas in its own power stations so that more of it can be shipped to Europe, President Aliyev said during an event at ADA University in Baku in April.

Azerbaijan is also planning to achieve “net zero” carbon emissions in Karabakh by 2050, as outlined in its latest national climate action plan (NDC) submitted under the UN climate process. It says that “to revitalise the territories liberated from occupation”, the government will establish “smart” settlements, promote “green” energy zones, agriculture and transport, and reforest “thousands of hectares”.

For Anna Ohanyan, a senior scholar in the Russia and Eurasia programme at the US-based Carnegie Endowment for International Peace, “it’s greenwashing of an ethnic cleansing, pure and simple”.

“Azerbaijan is putting a stamp on the territory as a way to legitimise the conquest of Nagorno-Karabakh and doing so under the pretence of helping fight climate change,” she told Climate Home.

The COP29 spokesperson said in emailed comments that this view “has no basis in fact”, adding that Azerbaijan is rebuilding houses for its citizens who were internally displaced during the conflict, “according to UN sustainability standards”.

Disputed territory

Territorial disputes over the Nagorno-Karabakh region have a long and complex history.

“Azerbaijan and Armenia – both are convinced this is historic patrimony of their people,” said Audrey Altstadt, a professor of history at the University of Massachusetts Amherst who specialises in Azerbaijan.

As the Soviet Union set about governing its far-flung provinces in the 1920s, then Commissar of Nationalities, Joseph Stalin, ruled that the region should be part of Soviet Azerbaijan, even though ethnic Armenians made up 94% of its population at the time.

In the 1980s, alongside the fall of the Soviet Union, tensions began to rise after Nagorno-Karabakh’s governing authorities declared their intention to join Armenia and Azerbaijan reacted by attempting to suppress separatists.

After the two sides gained independence from the Soviet Union in 1991, clashes between them escalated into an all-out war.

By the time fighting stopped three years later, Azerbaijan had suffered a crushing defeat, losing not just Nagorno-Karabakh but also a sizable chunk of territory around it. Ethnic Armenians declared a separatist republic in the region with the backing of Armenia.

Evolution of territorial control over Nagorno-Karabakh, and surrounding districts, from the aftermath of the 1994 war until today. Graphic: Fanis Kollias

Some 870,000 Azeris abandoned their homes in the captured area and Armenia itself, while around 300,000 ethnic Armenians fled Azerbaijan, according to the United Nations’ refugee agency.

For 15 years the conflict remained frozen, while international actors – led by the United States, France and Russia – tried, and failed, to find a peaceful resolution.

Azerbaijan’s autocratic president, Aliyev, took matters into his own hands in September 2020, mounting a large-scale military offensive on Nagorno-Karabakh. Powered by more sophisticated weaponry, and backed by Türkiye, Azeri forces prevailed during a 44-day war that claimed the lives of at least 7,000 people – including over 100 civilians.

Under a ceasefire agreement signed in November 2020, Azerbaijan gained a significant proportion of Nagorno-Karabakh, including the coveted town of Shushi – called Shusha by Azeris – as well as winning control of adjacent districts.

Soon afterwards, Baku announced a colossal programme to rebuild and repopulate the region, establishing “green energy zones” in Nagorno-Karabakh and East Zangezur.

Rebuilding ‘from scratch’

Deep behind a string of police checkpoints, the plan is proceeding apace. It includes Aghali, one of the “smart” villages created by the government to accommodate Azeri citizens displaced from the area three decades ago.

“Everything we build here, starting from houses to schools, is based on the element of solar,” said Vahid Hajiyev, special representative of the Azerbaijan presidency in Jabrayil, Gubadli and Zangilan districts, addressing a group of international reporters.

“The whole area had been devastated,” added Hajiyev, saying it was largely abandoned and littered with mines after Armenia captured it. “We’re doing everything from scratch and that gives an opportunity to do it right.”

A view of Aghali, a “smart” village created by the Azerbaijani government in the territories retaken from Armenia, in April 2024. Photo: Matteo Civillini

A nearby screw hydro turbine provides electricity for the whole village, while homes are equipped with solar water heating systems, officials told Climate Home.

“Smart agriculture” projects are being developed to give work to the more than 860 people who, according to government figures, have already moved into the village, with hundreds more expected to join them soon, they added.

Climate Home was not able to talk to any of the residents, besides government officials, and was not shown around the homes.

Aghali offers a template for around 30 similar villages the Azeri government plans to erect across the captured regions. They are just one part of the mammoth construction drive in the Karabakh area, bankrolled by Baku to the tune of just under $2.5 billion a year – around 12% of total public spending.

While the official vision projects an eco-paradise, in Baku’s breakneck drive to put it into practice, the landscape currently resembles a sprawling construction site, as seen by Climate Home and shown by satellite images.

Travelling up the windy road to Shusha-Shushi just before midnight, the headlights of dump trucks and cement mixers pierced the near-total darkness.

They are the backbone of a giant effort to lay down thousands of kilometres of roads and railways and throw up brand-new airports, vast conference halls, hotels and apartments.

Globally, construction is among the most polluting industries, contributing around 10% of global carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions in 2022, according to the UN Environment Programme (UNEP).

In March 2022, the Azerbaijan government invited observers from UNEP to assess the environmental situation in the territories it had gained, after accusing Armenians of large-scale destruction and contamination of the water and soil.

The UNEP team documented “chemical pollution of water” and “deforestation” as a result of activities in dozens of mines and quarries carried out by the Armenian administration “with inadequate environmental oversight and supervision”.

But it also found that Azerbaijan’s building drive, then still in its infancy, was already putting further strains on the environment, as well as causing climate-heating emissions, thereby “adversely impacting the zero-emission goal for the region”.

The construction of new roads was “having a significant impact on forest cover”, its report stated, while the infrastructure programme “placed a significant burden on finite natural raw materials” extracted from local quarries to make cement or asphalt.

The construction drive is altering the landscape in Nagorno-Karabakh. Photo: Matteo Civillini/April 2024

The COP29 spokesperson said Azerbaijan is following the recommendations of the UNEP report and that “a number of mitigation measures have been undertaken” to curb the environmental footprint of the works.

“We believe that the net impact of the reconstruction effort will actually contribute to Azerbaijan’s climate change and decarbonisation goal,” the spokesperson added.

Nagorno-Karabakh’s net zero target has yet to be extended to the rest of the country. Currently Azerbaijan has a goal to reduce emissions 40% by 2050 and has promised to submit a new NDC that is aligned with limiting global warming to 1.5C, which is due by early 2025.

Environmental blockade

In December 2022, environmental concerns became a weapon in the long-running dispute over Nagorno-Karabakh. Azerbaijani eco-activists blocked the Lachin Corridor, the only road connecting the region to the outside world and a vital supply line for food and medicines.

They were ostensibly demonstrating over the impact of mining in the breakaway region. But, according to close watchers of the conflict, the protesters had been sent there by Baku – a claim denied by the COP29 spokesperson.

At the time, one protester told Climate Home that representatives from the Ministry of the Environment were also present. On many other occasions, the Azerbaijan government has cracked down on political dissent, according to human rights groups.

When, four months later, Azerbaijan erected a permanent checkpoint on the road to “prevent the illegal transportation of manpower and weapons”, the sit-in ended. But the blockade of Nagorno-Karabakh continued with only limited amounts of aid trickling in.

Shortages of food, medications and fuel plunged the region into a humanitarian crisis, according to UN human rights experts.

“In the end, it was hard to even find bread. There were women and kids queuing all night for a piece of bread,” recalled Siranush Sargsyan, an Armenian journalist from Nagorno-Karabakh, in an interview with Climate Home. “Even if they didn’t kill all of us, they were basically starving people.”

On September 19 2023, Azeri forces launched a lightning attack on the parts of Nagorno-Karabakh still controlled by ethnic Armenians in what Baku called “an anti-terrorist operation”. Within 24 hours, the de-facto government of the enclave surrendered and announced the republic would cease to exist the following January.

Fearing violence and persecution, over 100,000 ethnic Armenians – nearly the entire remaining population – fled their homes in Nagorno-Karabakh and sought refuge in Armenia.

Refugees from Nagorno-Karabakh region arrive at the Armenian border in a truck in September 2023. REUTERS/Irakli Gedenidze

“[The] liberation of territories was a main goal of my political life. And I’m proud that these goals have been achieved,” President Aliyev, whose family has ruled over Azerbaijan for the past 31 years, said last December. “I think we brought peace. We brought peace by war.”

Now in full control of Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan is doubling down on its efforts to reshape the region and move tens of thousands of Azeris there. “We will continue the ‘Great Return’ campaign until all those who were forced from their homes can go home,” the COP29 spokesperson said, referring to internally displaced Azeris.

Government officials told Climate Home that ethnic Armenians are also welcome to go back, but only if they stick to the conditions imposed by Baku.

Journalist Sargsyan said returning to Nagorno-Karabakh under Azeri control is out of the question as she fears for her safety. “I left everything there”, she said. “But I would rather die than end up in a prison in Azerbaijan.”

Heritage destruction

Meanwhile, ethnic Armenians fear the huge Azeri construction drive now underway will erase most, if not all, of their legacy.

Nijat Karimov, a special adviser to Azerbaijan’s presidency, told Climate Home that Baku had destroyed Armenian government buildings in Nagorno-Karabakh for “safety” reasons, without giving specifics. He added that Azerbaijan’s government had since “repaired and rehabilitated” the villages.

A day later, Climate Home travelled past what little remains of Karintak village (known as Dashalti in Azeri). Nestled in a gorge sitting just below Shusha-Shushi, it was home to a few hundred ethnic Armenians until Azeri forces took over at the end of 2020.

Now nearly the entire settlement appears to have been razed to the ground, as Climate Home witnessed. Mounds of disturbed soil surround a large mosque, under construction, and a church, one of the few original buildings left standing.

The village of Karintak (bottom right corner), as seen in April 2024 when Climate Home was taken through the region. Photo: Matteo Civillini

Climate Home asked the COP29 Presidency what had happened to the village. A spokesperson said government experts would need to examine the satellite images, buildings and sites referenced in Climate Home’s question “to get a complete answer”.

The case of Karintak is not an isolated one, according to Caucasus Heritage Watch, a research group led by archaeologists at Cornell and Purdue Universities. They have documented the destruction of at least eight Armenian cultural heritage sites – including churches and a cemetery – in the retaken territories since 2021.

Lucrative contracts

Baku says its grand vision is to repopulate Nagorno-Karabakh and the neighbouring areas, attract foreign business and eventually turn them into tourism destinations. But when Climate Home visited, most of what had been built appeared to be under-used, while access to the region is severely restricted.

Two international airports, completed in just 10-15 months a mere 70 km apart, have very little air traffic, except for the occasional charter flight, tracking data shows. A third airfield is now being erected nearby.

In Shusha-Shushi, a five-star spa hotel complex with sleek marble interiors was inaugurated just over a year ago. When Climate Home walked past last month, there was not a client in sight, with only wandering labourers headed to nearby construction sites.

The 5-star Shusha Hotel appeared empty when Climate Home visited in April 2024. Photo: Matteo Civillini

Historian Altstadt said the reconstruction is being driven by multiple incentives. “Yes, it is to get people back to the land they left over 30 years ago, and it is also to put their stamp on it to show ‘this is our territory and we can do what we want’,” she told Climate Home. “But there is also a lot of money to be made by Azerbaijan’s oligarchs.”

Pasha Holding is a conglomerate controlled by the powerful Pashayev family of First Lady Mehriban Aliyeva. It is heavily involved in the rebuilding of Nagorno-Karabakh. It also manages huge tracts of agricultural land and new hotels, and is opening bank branches and supermarkets.

The vast amount of money – and assets – up for grabs is also attracting considerable foreign interest.

Turkish firm Kalyon – considered to have close ties to Prime Minister Recep Tayyip Erdogan, according to Reporters Without Borders – has won major construction contracts in the territories. And mining permits in Karabakh have been awarded to a group run by pro-Erdogan businessman Mehmet Cengiz.

How to fix the finance flows that are pushing our planet to the brink

British architects Chapman Taylor are earning at least $2.3 million to map out the redevelopment of Shusha-Shushi – which thousands of ethnic Armenians fled following Azeri attacks in 2020 – and will also work on the urban design of other towns.

BP, meanwhile, is developing a 240-megawatt solar power plant in Jabrayil district, with construction expected to begin later this year. Speaking at Baku Energy Week in 2022, Gary Jones, the energy firm’s regional president for Azerbaijan, Georgia and Turkey, praised Baku’s efforts to turn Karabakh into “the heart of sustainable development”.

Adopting contested terminology used by Azerbaijan, he said the “liberated territories” are “blessed with some of the country’s best solar and geothermal resources”, creating the “perfect opportunity for a fully net zero system” that “can be built fresh from a new start”.

BP and Chapman Taylor did not respond to Climate Home’s request for comment.

Special presidential representative Hajiyev told Climate Home that many international companies are interested in working in Karabakh. “It’s a huge investment opportunity because a lot of government incentives are provided here,” he said.

(Reporting by Matteo Civillini in Azerbaijan; editing by Megan Rowling and Joe Lo; fact-checking by Sebastian Rodriguez)

Matteo Civillini visited Nagorno-Karabakh, and the surrounding districts, as part of an “energy media tour” organised and sponsored by the COP29 Presidency.

The post In Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan’s net zero vision clashes with legacy of war appeared first on Climate Home News.

In Nagorno-Karabakh, Azerbaijan’s net zero vision clashes with legacy of war

Climate Change

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

The country’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas benefited from what critics say is a questionable IRS interpretation of tax credits.

Cheniere Energy, the largest producer and exporter of U.S. liquefied natural gas, received $370 million from the IRS in the first quarter of 2026, a payout that shipping experts, tax specialists and a U.S. senator say the company never should have received.

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

Climate Change

DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Absolute State of the Union

‘DRILL, BABY’: US president Donald Trump “doubled down on his ‘drill, baby, drill’ agenda” in his State of the Union (SOTU) address, said the Los Angeles Times. He “tout[ed] his support of the fossil-fuel industry and renew[ed] his focus on electricity affordability”, reported the Financial Times. Trump also attacked the “green new scam”, noted Carbon Brief’s SOTU tracker.

COAL REPRIEVE: Earlier in the week, the Trump administration had watered down limits on mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants, reported the Financial Times. It remains “unclear” if this will be enough to prevent the decline of coal power, said Bloomberg, in the face of lower-cost gas and renewables. Reuters noted that US coal plants are “ageing”.

OIL STAY: The US Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments brought by the oil industry in a “major lawsuit”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper said the firms are attempting to head off dozens of other lawsuits at state level, relating to their role in global warming.

SHIP-SHILLING: The Trump administration is working to “kill” a global carbon levy on shipping “permanently”, reported Politico, after succeeding in delaying the measure late last year. The Guardian said US “bullying” could be “paying off”, after Panama signalled it was reversing its support for the levy in a proposal submitted to the UN shipping body.

Around the world

- RARE EARTHS: The governments of Brazil and India signed a deal on rare earths, said the Times of India, as well as agreeing to collaborate on renewable energy.

- HEAT ROLLBACK: German homes will be allowed to continue installing gas and oil heating, under watered-down government plans covered by Clean Energy Wire.

- BRAZIL FLOODS: At least 53 people died in floods in the state of Minas Gerais, after some areas saw 170mm of rain in a few hours, reported CNN Brasil.

- ITALY’S ATTACK: Italy is calling for the EU to “suspend” its emissions trading system (ETS) ahead of a review later this year, said Politico.

- COOKSTOVE CREDITS: The first-ever carbon credits under the Paris Agreement have been issued to a cookstove project in Myanmar, said Climate Home News.

- SAUDI SOLAR: Turkey has signed a “major” solar deal that will see Saudi firm ACWA building 2 gigawatts in the country, according to Agence France-Presse.

$467 billion

The profits made by five major oil firms since prices spiked following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine four years ago, according to a report by Global Witness covered by BusinessGreen.

Latest climate research

- Claims about the “fingerprint” of human-caused climate change, made in a recent US Department of Energy report, are “factually incorrect” | AGU Advances

- Large lakes in the Congo Basin are releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere from “immense ancient stores” | Nature Geoscience

- Shared Socioeconomic Pathways – scenarios used regularly in climate modelling – underrepresent “narratives explicitly centring on democratic principles such as participation, accountability and justice” | npj Climate Action

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

The constituency of Richard Tice MP, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of Reform UK, is the second-largest recipient of flood defence spending in England, according to new Carbon Brief analysis. Overall, the funding is disproportionately targeted at coastal and urban areas, many of which have Conservative or Liberal Democrat MPs.

Spotlight

Is there really a UK ‘greenlash’?

This week, after a historic Green Party byelection win, Carbon Brief looks at whether there really is a “greenlash” against climate policy in the UK.

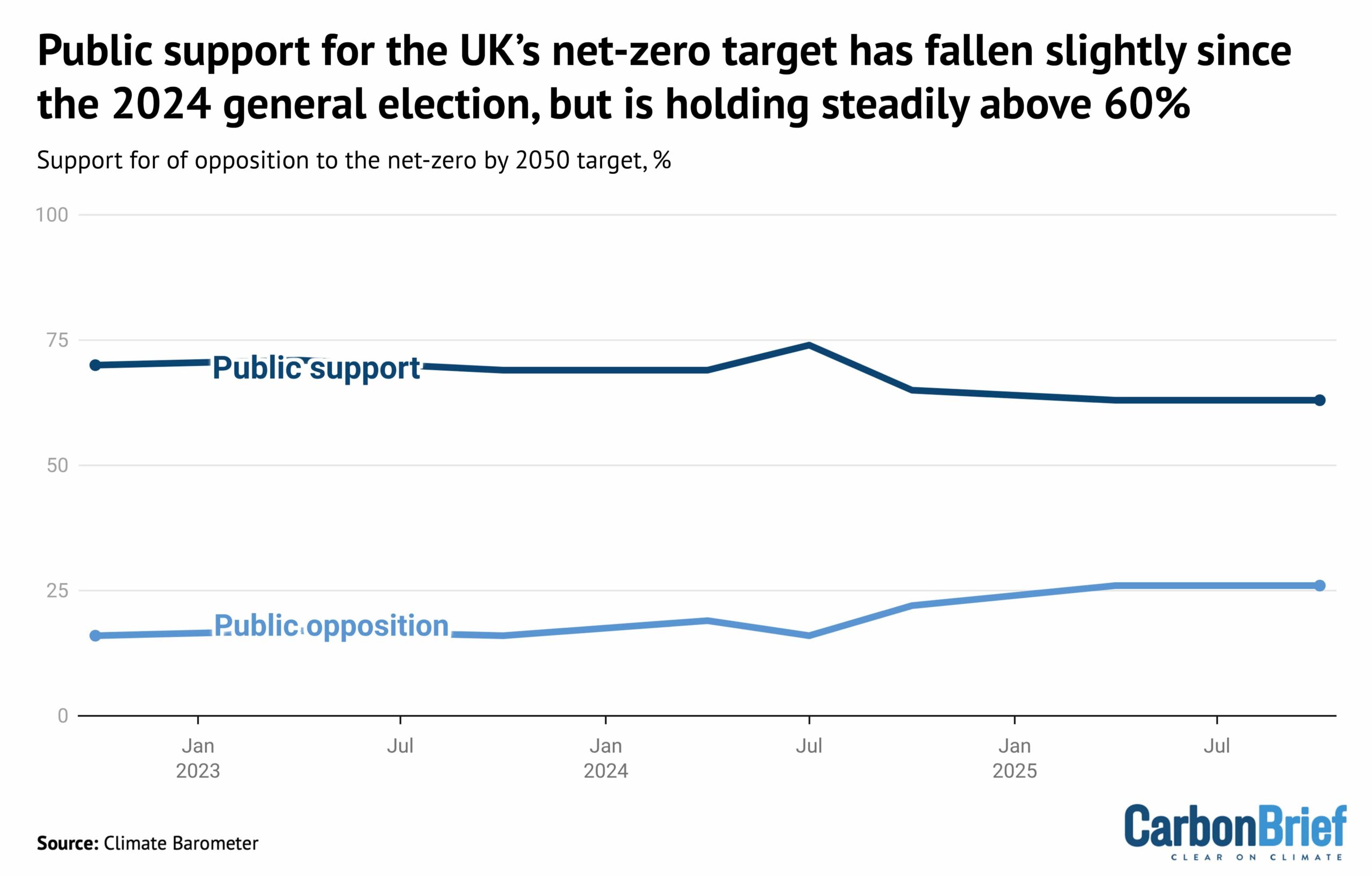

Over the past year, the UK’s political consensus on climate change has been shattered.

Yet despite a sharp turn against climate action among right-wing politicians and right-leaning media outlets, UK public support for climate action remains strong.

Prof Federica Genovese, who studies climate politics at the University of Oxford, told Carbon Brief:

“The current ‘war’ on green policy is mostly driven by media and political elites, not by the public.”

Indeed, there is still a greater than two-to-one majority among the UK public in favour of the country’s legally binding target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, as shown below.

Steve Akehurst, director of public-opinion research initiative Persuasion UK, also noted the growing divide between the public and “elites”. He told Carbon Brief:

“The biggest movement is, without doubt, in media and elite opinion. There is a bit more polarisation and opposition [to climate action] among voters, but it’s typically no more than 20-25% and mostly confined within core Reform voters.”

Conservative gear shift

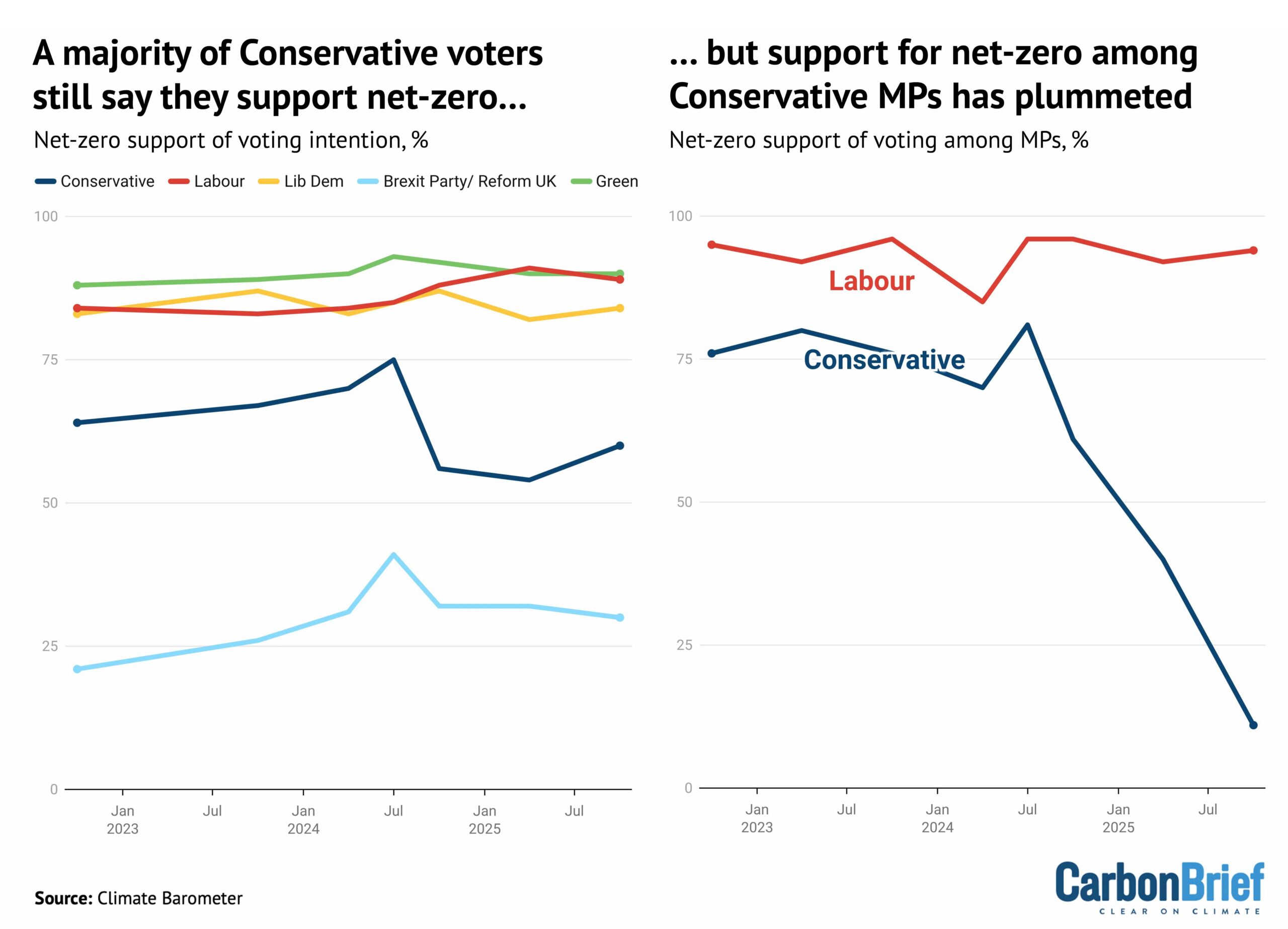

For decades, the UK had enjoyed strong, cross-party political support for climate action.

Lord Deben, the Conservative peer and former chair of the Climate Change Committee, told Carbon Brief that the UK’s landmark 2008 Climate Change Act had been born of this cross-party consensus, saying “all parties supported it”.

Since their landslide loss at the 2024 election, however, the Conservatives have turned against the UK’s target of net-zero emissions by 2050, which they legislated for in 2019.

Curiously, while opposition to net-zero has surged among Conservative MPs, there is majority support for the target among those that plan to vote for the party, as shown below.

Dr Adam Corner, advisor to the Climate Barometer initiative that tracks public opinion on climate change, told Carbon Brief that those who currently plan to vote Reform are the only segment who “tend to be more opposed to net-zero goals”. He said:

“Despite the rise in hostile media coverage and the collapse of the political consensus, we find that public support for the net-zero by 2050 target is plateauing – not plummeting.”

Reform, which rejects the scientific evidence on global warming and campaigns against net-zero, has been leading the polls for a year. (However, it was comfortably beaten by the Greens in yesterday’s Gorton and Denton byelection.)

Corner acknowledged that “some of the anti-net zero noise…[is] showing up in our data”, adding:

“We see rising concerns about the near-term costs of policies and an uptick in people [falsely] attributing high energy bills to climate initiatives.”

But Akehurst said that, rather than a big fall in public support, there had been a drop in the “salience” of climate action:

“So many other issues [are] competing for their attention.”

UK newspapers published more editorials opposing climate action than supporting it for the first time on record in 2025, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Global ‘greenlash’?

All of this sits against a challenging global backdrop, in which US president Donald Trump has been repeating climate-sceptic talking points and rolling back related policy.

At the same time, prominent figures have been calling for a change in climate strategy, sold variously as a “reset”, a “pivot”, as “realism”, or as “pragmatism”.

Genovese said that “far-right leaders have succeeded in the past 10 years in capturing net-zero as a poster child of things they are ‘fighting against’”.

She added that “much of this is fodder for conservative media and this whole ecosystem is essentially driving what we call the ‘greenlash’”.

Corner said the “disconnect” between elite views and the wider public “can create problems” – for example, “MPs consistently underestimate support for renewables”. He added:

“There is clearly a risk that the public starts to disengage too, if not enough positive voices are countering the negative ones.”

Watch, read, listen

TRUMP’S ‘PETROSTATE’: The US is becoming a “petrostate” that will be “sicker and poorer”, wrote Financial Times associate editor Rana Forohaar.

RHETORIC VS REALITY: Despite a “political mood [that] has darkened”, there is “more green stuff being installed than ever”, said New York Times columnist David Wallace-Wells.

CHINA’S ‘REVOLUTION’: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast reported from China on the “green energy revolution” taking place in the country.

Coming up

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean, Brasília

- 3 March: UK spring statement

- 4-11 March: China’s “two sessions”

- 5 March: Nepal elections

Pick of the jobs

- The Guardian, senior reporter, climate justice | Salary: $123,000-$135,000. Location: New York or Washington DC

- China-Global South Project, non-resident fellow, climate change | Salary: Up to $1,000 a month. Location: Remote

- University of East Anglia, PhD in mobilising community-based climate action through co-designed sports and wellbeing interventions | Salary: Stipend (unknown amount). Location: Norwich, UK

- TABLE and the University of São Paulo, Brazil, postdoctoral researcher in food system narratives | Salary: Unknown. Location: Pirassununga, Brazil

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

Seven Pacific island nations say they will demand heftier levies on global shipping emissions if opponents of a green deal for the industry succeed in reopening negotiations on the stalled accord.

The United States and Saudi Arabia persuaded countries not to grant final approval to the International Maritime Organization’s Net-Zero Framework (NZF) in October and they are now leading a drive for changes to the deal.

In a joint submission seen by Climate Home News, the seven climate-vulnerable Pacific countries said the framework was already a “fragile compromise”, and vowed to push for a universal levy on all ship emissions, as well as higher fees . The deal currently stipulates that fees will be charged when a vessel’s emissions exceed a certain level.

“For many countries, the NZF represents the absolute limit of what they can accept,” said the unpublished submission by Fiji, Kiribati, Vanuatu, Nauru, Palau, Tuvalu and the Solomon Islands.

The countries said a universal levy and higher charges on shipping would raise more funds to enable a “just and equitable transition leaving no country behind”. They added, however, that “despite its many shortcomings”, the framework should be adopted later this year.

US allies want exemption for ‘transition fuels’

The previous attempt to adopt the framework failed after governments narrowly voted to postpone it by a year. Ahead of the vote, the US threatened governments and their officials with sanctions, tariffs and visa restrictions – and President Donald Trump called the framework a “Green New Scam Tax on Shipping”.

Since then, Liberia – an African nation with a major low-tax shipping registry headquartered in the US state of Virginia – has proposed a new measure under which, rather than staying fixed under the NZF, ships’ emissions intensity targets change depending on “demonstrated uptake” of both “low-carbon and zero-carbon fuels”.

The proposal places stringent conditions on what fuels are taken into consideration when setting these targets, stressing that the low- and zero-carbon fuels should be “scalable”, not cost more than 15% more than standard marine fuels and should be available at “sufficient ports worldwide”.

This proposal would not “penalise transitional fuels” like natural gas and biofuels, they said. In the last decade, the US has built a host of large liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals, which the Trump administration is lobbying other countries to purchase from.

The draft motion, seen by Climate Home News, was co-sponsored by US ally Argentina and also by Panama, a shipping hub whose canal the US has threatened to annex. Both countries voted with the US to postpone the last vote on adopting the framework.

The IMO’s Panamanian head Arsenio Dominguez told reporters in January that changes to the framework were now possible.

“It is clear from what happened last year that we need to look into the concerns that have been expressed [and] … make sure that they are somehow addressed within the framework,” he said.

Patchwork of levies

While the European Union pushed firmly for the framework’s adoption, two of its shipping-reliant member states – Greece and Cyprus – abstained in October’s vote.

After a meeting between the Greek shipping minister and Saudi Arabia’s energy minister in January, Greece said a “common position” united Greece, Saudi Arabia and the US on the framework.

If the NZF or a similar instrument is not adopted, the IMO has warned that there will be a patchwork of differing regional levies on pollution – like the EU’s emissions trading system for ships visiting its ports – which will be complicated and expensive to comply with.

This would mean that only countries with their own levies and with lots of ships visiting their ports would raise funds, making it harder for other nations to fund green investments in their ports, seafarers and shipping companies. In contrast, under the NZF, revenues would be disbursed by the IMO to all nations based on set criteria.

Anais Rios, shipping policy officer from green campaign group Seas At Risk, told Climate Home News the proposal by the Pacific nations for a levy on all shipping emissions – not just those above a certain threshold – was “the most credible way to meet the IMO’s climate goals”.

“With geopolitics reframing climate policy, asking the IMO to reopen the discussion on the universal levy is the only way to decarbonise shipping whilst bringing revenue to manage impacts fairly,” Rios said.

“It is […] far stronger than the Net-Zero Framework that is currently on offer.”

The post Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen appeared first on Climate Home News.

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits