The global shift towards a clean-energy system is much more than just a technological switch – it is a profound transformation of markets, industries and societal behaviours.

This complex undertaking is often characterised by “non-linearity” and “feedback loops”, where small changes can go on to have disproportionately large impacts and where seemingly straightforward paths encounter unexpected roadblocks.

Interventions can be self-amplifying – leading to runaway change, or they can be self-defeating – when progress seems impossible to attain.

Our new policy brief sheds light on these intricate dynamics, which can be overlooked when governments use analytical frameworks based on standard economic thinking.

The brief sets out the most common archetypes of system change and behaviour, as well as the underlying feedback loops that drive them, with the aim of helping policymakers to understand the recurring patterns that can either accelerate or impede progress.

Governments that can recognise these patterns – as well as the ways they can be harnessed or sidestepped – are likely to be better equipped to manage structural change.

This article delves into three key examples from the policy brief, exploring how they are influencing the energy transition and what lessons can be drawn for effective policymaking.

Reinforcing feedback loops

At the heart of the energy transition lies a powerful engine: the reinforcing feedback loops inherent in the development and diffusion of many clean-energy technologies.

This virtuous cycle operates through several mechanisms.

First, “learning by doing”, which means that as more units of a technology, such as solar panels or wind turbines, are produced and deployed, manufacturers and developers become more efficient, processes are refined and costs fall.

Second, economies of scale kick in: as production volumes increase, unit costs decrease due to efficiencies in manufacturing and more developed supply chains.

Finally, wider deployment can trigger network effects and the emergence of complementary innovations. This means that as the adoption of a given technology grows, it can foster an ecosystem of supporting infrastructure, skilled labour and supporting technologies, which can further boost its attractiveness and viability.

Together, these three elements create a powerful reinforcing loop: initial investment drives innovation and cost reduction, which spurs increased demand, attracting further investment.

Solar photovoltaics (PV) and wind turbines are prime examples of this dynamic.

The astonishing growth of solar offers a particularly vivid illustration of the way in which reinforcing feedback loops can blindside experts and policymakers alike.

Solar growth has far exceeded projections made in the early 2000s. Indeed, the world’s actual installed capacity in 2020 was over 700 gigawatts (GW), more than ten times the level expected in outlooks published in 2006, as shown in the figure below.

Global solar deployment has exceeded expectations due to disparate trends and drivers in individual markets that, together, all point in the same direction. China, for instance, met its 2030 target for wind and solar capacity six years ahead of schedule in 2024.

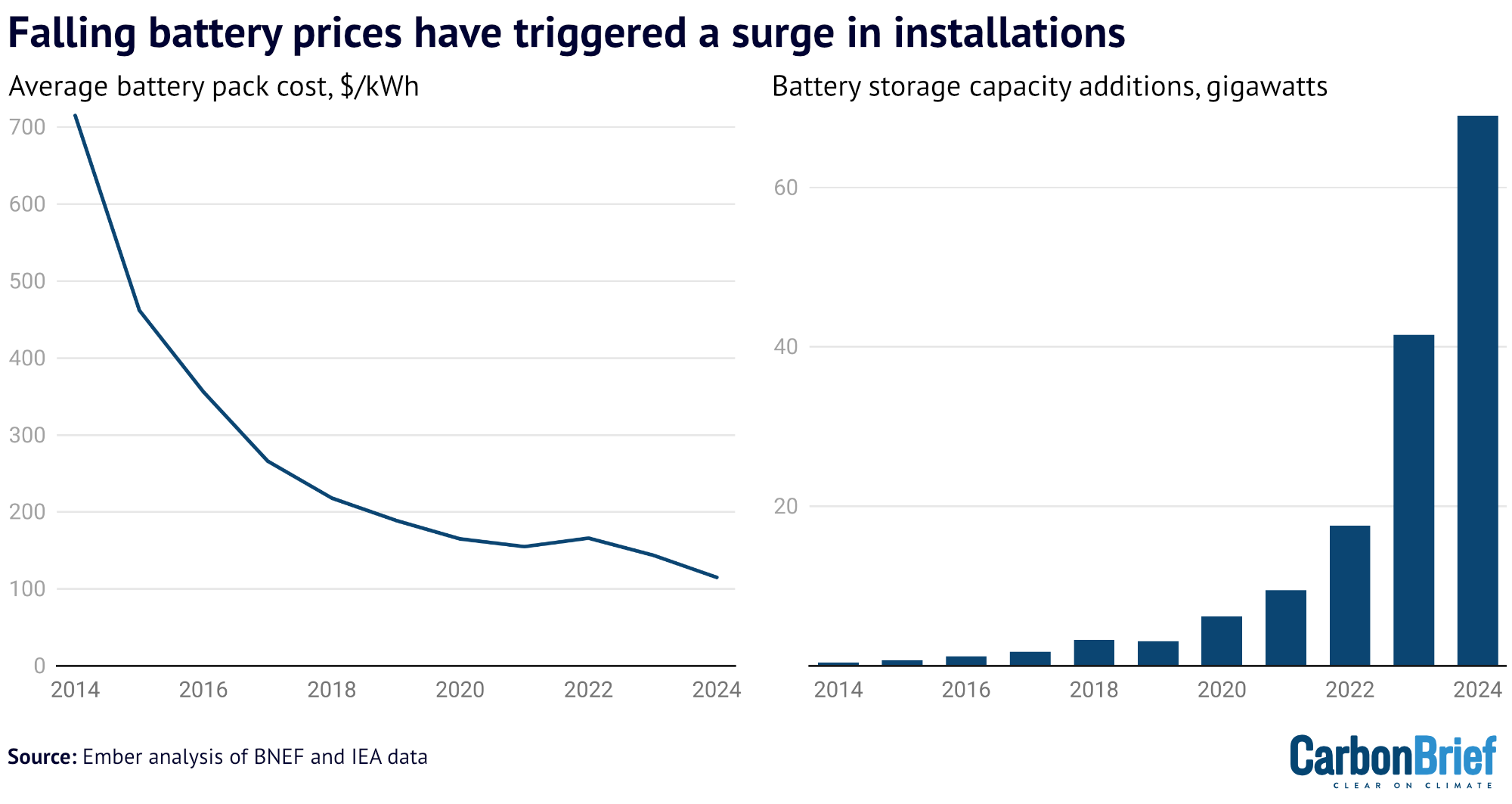

Batteries are also riding this wave, with costs plummeting by around 85% over the past decade as deployment, particularly in road transport, scales up.

However, not all clean-energy technologies benefit from this self-amplifying pattern.

Nuclear power and hydropower, for example, have historically not shown the same rapid cost declines, due to their large, complex and site-specific nature. This contrasts with the smaller, modular and replicable characteristics of technologies, such as solar PV.

This does not negate the potential role of such technologies, but it does mean that they are less likely to see disruptive, exponential and self-reinforcing growth.

There are a number of potential conclusions for policymakers.

Early in the transition, interventions such as feed-in tariffs and public procurement were crucial in kick-starting these reinforcing feedbacks for solar and wind.

As these technologies mature and become cost-competitive, the focus shifts to removing other barriers, such as streamlining permitting processes, investing in grid expansion and reforming markets so they are better able to integrate variable renewable output.

These same principles could now be applied to newly emergent clean-energy technologies. Policies that directly nurture these reinforcing loops, such as deployment subsidies and clean technology mandates, can be expected to be most effective in the initial stages.

Turning again to the example of solar energy, while such initial efforts appeared to be expensive, they paid off over time by unlocking future cost reductions and, thus, kick-starting the self-amplifying feedback loops that are now driving further progress.

This contrasts with the idea that carbon pricing is necessarily the most efficient policy for decarbonisation. It may well be helpful, but as it will not drive rapid early technology adoption, it is less likely to have a self-amplifying effect in the initial stages of the transition.

Renewable ‘cannibalisation’

While the growth of renewable energy is the driving force of the energy transition, another system dynamic, termed “renewable cannibalisation“, can act as a dampening feedback loop. This can potentially slow progress long before full decarbonisation is achieved

This cannibalisation process results in variable renewable energy (VRE) sources, such as solar and wind, receiving decreasing prices for the electricity they generate.

Essentially, the more solar and wind capacity that is connected to the grid, the more they undermine their own revenue. This happens through three main channels.

First, the merit order effect, whereby solar and wind, which have very low operating costs, push more expensive fossil-fuel generators out of the market when supply is abundant.

In markets with marginal pricing, this leads to lower wholesale electricity prices during periods of high renewable output. While this cuts prices for consumers – at least in the short term – these lower prices also reduce revenues for renewable generators, potentially undermining the economic case for further investment.

For example, in California, solar power unit revenues fell by $1.30 per megawatt hour (MWh) for each percentage point increase in solar penetration between 2013 and 2017.

Second, price volatility, where uncertainty over future trends in the generation mix and the balance between supply and demand can make long-term revenues difficult to predict.

This increased uncertainty can raise the cost of capital for new renewable projects, again acting as a brake on investment

The UK, for example, experienced this before the introduction of “contracts for difference” (CfDs), which helped stabilise revenue expectations for renewable developers.

Third, volume risk, where rising VRE capacity increases the likelihood of more frequent curtailment – periods when renewable generation exceeds demand or grid capacity, forcing generators to scale back output and lose potential revenue.

Curtailment in itself is nothing new, but the scale and frequency is changing. Recent analysis by University College London suggests that without significant flexibility or storage, UK renewable generation could exceed demand for more than 50% of the time by 2030.

The analysis found that installed wind and solar capacity is set to surge beyond current levels of electricity demand, as illustrated in the figure below, finding that this could “deter investment” in new projects if no action is taken to address the problem.

These dampening feedback loops illustrate a classic “limits to success” scenario. The very success of renewables, if unmanaged, can create conditions that hinder their continued expansion.

The policy implications here are nuanced. One solution is CfDs, which offer renewable generators a fixed price and have been effective in many countries at mitigating the merit order effect and price volatility, thus maintaining investment.

However, as VRE penetration becomes very high and surplus generation becomes a regular occurrence, other solutions are likely to be needed. This is because existing CfD designs often include clauses that stop payments when market prices drop below zero.

As a result, alternative CfD designs, guaranteeing revenues based on installed capacity or potential – rather than actual – electricity generation might be considered, for example, even though these have other drawbacks.

More fundamentally, our research suggests the solution to this challenge lies in fostering the co-evolution of renewables with technologies such as energy storage and green hydrogen production. These can absorb surplus generation and turn a problem into an opportunity.

Whereas, traditionally, it might be assumed that the market on its own can optimally allocate risk, research suggests that a redesign of market structures may be needed to enable investment and fully realise the cost-saving opportunities of the new technologies.

This is one of several sets of feedbacks discussed in a separate new report published today, looking at the power sector transition in China.

The power of connection

The energy transition is not a series of isolated changes in different sectors. Instead, it is an interconnected system, where progress in one area can catalyse shifts elsewhere. Shared technologies can create reinforcing feedbacks that accelerate decarbonisation across multiple fronts, generating cross-sector synergies.

The relationship between clean power and transport electrification is a powerful example of this. As batteries are deployed at scale in electric vehicles (EVs), their costs fall, enabling ever-wider deployment and further cost declines, as shown in the chart below.

This is due to the learning-by-doing and economies-of-scale feedbacks discussed above.

This cost reduction then makes batteries more viable for grid-scale energy storage, which, in tur, helps integrate more low-cost VRE into the power system.

Cheaper, cleaner electricity then further incentivises the electrification of transport, as well as heating and light industry. This increased electrification boosts demand for renewable power, driving further deployment and cost reductions in solar and wind. It also expands the potential for demand-side response, where consumers adjust their electricity use to help balance the grid.

A similar dynamic is anticipated for “green” hydrogen. As deployment in one anchor sector – perhaps fertilisers or refining – drives down the cost of electrolysers, it makes green hydrogen more competitive for other applications, such as shipping or even long-duration energy storage in the power sector.

Each sector’s adoption of green hydrogen contributes to the shared learning and cost reduction, benefiting all.

The policy implications of these cross-sector synergies could be significant. Their existence suggests, for example, that there is no need to wait for decarbonisation of the power sector to advance further, before beginning the electrification of transport, heating or industry.

This is in contrast to the argument that transport should only be electrified after cutting power sector emissions, since increased EV charging will drive up demand for gas- or coal-fired generation.

While there will be a marginal increase in emissions from plugging a new EV into the power grid, the insights described in our brief imply that it is still likely to be more effective to pursue the transition away from fossil fuels in multiple sectors in parallel, because it can activate beneficial cross-sector feedback loops that are greater than the sum of their parts.

As such, our research suggests that policymakers hoping to take advantage of cross-sector synergies could aim to deliberately strengthen technological linkages between different parts of the energy system. Examples include electricity tariffs and market structures that reward “smart” EV charging and vehicle-to-grid (V2G) services, encouraging industrial participation in demand-side response and promoting integrated home energy systems. These interactions can amplify the benefits of early investment in the transition.

Policy insights from system dynamics

Archetypes such as the self-reinforcing growth of clean technologies, the potential for renewable cannibalisation, the accelerating power of cross-sector synergies and seven others described in our new report paint a picture of a transition that is far from linear. Instead, we find that it is governed by complex interdependencies and feedback loops.

Consequently, our research suggests that policymakers will be much better equipped to manage and steer the transition, if they adopt a systems thinking approach.

Recognising these recurring patterns allows for the design of more robust and effective policies that anticipate challenges and leverage opportunities.

For instance, understanding the power of reinforcing feedback loops in technology diffusion underscores the value of early-stage support for nascent clean-energy technologies.

Conversely, anticipating the dampening effects of renewable cannibalisation highlights the likely benefits of combining renewable buildout with evolving market designs and strategic investments in flexibility solutions, such as storage and demand-side response.

Policymakers that understand and work with these dynamics are likely to be in a better position to spark self-amplifying changes – achieving maximum value for minimum effort – and to avoid self-defeating interventions that go nowhere.

The post Guest post: How ‘feedback loops’ and ‘non-linear thinking’ can inform climate policy appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Guest post: How ‘feedback loops’ and ‘non-linear thinking’ can inform climate policy

Climate Change

US Government Is Accelerating Coral Reef Collapse, Scientists Warn

Proposed Endangered Species Act rollbacks and military expansions are leaving the Pacific’s most diverse coral reefs legally defenseless.

Ritidian Point, at the northern tip of Guam, is home to an ancient limestone forest with panoramic vistas of warm Pacific waters. Stand here in early spring and you might just be lucky enough to witness a breaching humpback whale as they migrate past. But listen and you’ll be struck by the cacophony of the island’s live-fire testing range.

US Government Is Accelerating Coral Reef Collapse, Scientists Warn

Climate Change

Satellites Reveal New Climate Threat to Emperor Penguins

Ice loss in the Antarctic Ocean may be killing the sea birds during their molting season.

Each year for millennia, emperor penguins have molted on coastal sea ice that remained stable until late summer—a haven during a span of several weeks when it’s dangerous for the mostly aquatic birds to enter the ocean to feed because they are regrowing their waterproof feathers.

Climate Change

States Sue to Block Trump’s ‘Anti-Science’ Vaccine Policy

Climate change helps spread vaccine-preventable diseases. But the Trump administration’s reduced vaccine schedule “throws science out the window,” and makes Americans more vulnerable to infections, state attorneys general charge in a new lawsuit.

Scientists have long warned that a warming world is likely to hasten the spread of infectious diseases, making vaccination even more critical to safeguard public health.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits