Countries have agreed at the resumed COP16 talks in Rome to a strategy for “mobilising” at least $200bn per year by 2030 to help developing countries conserve biodiversity.

Nations also agreed for the first time to a “permanent arrangement” for providing biodiversity finance to developing nations, “future-proofing” the flow of funds past 2030.

Faced with a highly unstable geopolitical landscape and a previous set of talks that ended in disarray in Colombia, countries forged a path to consensus on a set of texts in what many nations celebrated as a win for multilateralism in uncertain times.

The agreement on finance comes despite the world’s largest biodiversity donor – the US, which has never been a formal party within these talks – recently deciding to withdraw most of its nature funding in a foreign-aid freeze under Donald Trump.

Many European countries who signed onto the agreement have also recently cut their aid budgets.

Nations also agreed on two texts for tracking their progress towards achieving the targets of the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

The GBF is a landmark deal first made in 2022 aiming to halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030.

Colombian politician and COP16 president Susana Muhamad received a lengthy standing ovation for her role in guiding parties to consensus in the early hours of Friday morning in Rome.

But, amid celebrations, some countries cautioned that a vast amount of progress will be needed to have a chance of halting and reversing biodiversity loss in just five years.

Some three-quarters of nations have still not submitted their UN biodiversity plans for how they will achieve the targets of the GBF – four months after the deadline.

And a recent investigation by Carbon Brief and the Guardian revealed that more than half of nations that have submitted UN biodiversity plans do not commit to the GBF’s flagship target of protecting 30% of land and seas for nature by 2030.

- COP16’s back story

- Finance

- Global review

- Monitoring framework

- Cooperation with other conventions

- Around the COP

COP16’s back story

COP16 was the first UN biodiversity summit following the adoption in 2022 of a landmark agreement, known as the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), at COP15. The overall goal of the GBF is to “halt and reverse biodiversity” loss by 2030, through four goals and 23 targets.

At COP16, many issues centred around the “means of implementation” of the GBF. Initially, the conference was set to take place in Turkey, but the country withdrew from hosting it after a series of destructive earthquakes. Colombia took on the organisation of the summit and Cali was named as host city in February 2024.

In Cali, countries agreed on a new fund for the sharing of benefits from the use of genetic data, the creation of a dedicated subsidiary body for Indigenous peoples and local communities and a new process to identify ecologically and biologically significant marine areas.

However, the final plenary ran through the night, owing to disagreements over biodiversity finance. With many delegations needing to catch flights home, COP16 was suspended the following morning due to a lack of the “quorum” needed to reach consensus.

Later that month, the COP16 presidency stated that the negotiations would be resumed in the new year to “address outstanding issues on finance and complete the mandate of this COP”.

Among the pending items left over from Cali was a new strategy for “resource mobilisation”, aimed at allocating $200bn annually for biodiversity conservation “from all sources” by 2030.

Alongside that, countries needed to agree on the mechanism for distributing funds. Global-south countries urged the creation of a new global fund for biodiversity, to be under the control of the COP. Meanwhile, global-north countries argued for maintaining the current fund, which is housed under the Global Environment Facility (GEF), a multilateral fund set up in the early 1990s to “support developing countries’ work to address the world’s most pressing environmental issues”.

Countries also had to revisit the monitoring framework for the implementation of the GBF, which seeks to “provide the common yardsticks that parties will use to measure progress against the 23 targets” of the GBF, according to the CBD.

Parties also failed to agree on a new text outlining the process for a global review of national biodiversity strategies and action plans (NBSAPs) at COP17 in Armenia in 2026 and COP19, four years later.

The CBD took up the remaining issues in two “resumed” sessions of COP16.

The first of these meetings, to approve the budget, was held in December under “silence procedure” – meaning the text was circulated and parties given a period of time to respond with any objections. The second resumed session was held in person at the headquarters of the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) in Rome, from 25 to 27 February 2025, to address all remaining decisions.

Finance

Post-2030 fund

The fight over a new, dedicated global biodiversity fund – the subject of fraught negotiations in Nairobi, Montreal and Cali – dominated the agenda at the resumed COP16 nature talks in Rome.

As a whole, COP16 was supposed to deliver a strategy for raising funds to assist countries in implementing the “ambitious” nature deal struck at COP15.

It was also expected to deliver a financial mechanism under the COP to provide developing countries with the means to meet biodiversity goals and targets.

At the resumed COP16 talks in Rome, countries made history by agreeing to set up a “permanent arrangement for the financial mechanism” under the COP by 2030 – a decision that is decades in the works.

While the decision does not establish a brand new fund immediately, it is “future proofing” global biodiversity finance beyond 2030, Georgina Chandler from the Zoological Society of London told a press briefing. The text leaves open the form that the finance will take – either under a new entity, or as part of existing funding instruments that biodiverse countries have been seeking to reform.

A permanent financial mechanism is the “unfinished business of the COP, 30 years in the making”, said Lim Li Ching from the Third World Network. While there is much to be debated at successive COPs, “at least the mechanism is locked in”, she told Carbon Brief.

The resumed COP16 also saw countries agree on a roadmap to develop the financial mechanism, reform existing financial institutions and mobilise funding from “all sources” to close the $200bn per year biodiversity funding gap.

To speed up raising these resources, the text asks the executive secretary of the CBD to “facilitate an international dialogue” of ministers of environment and finance from developing and developed countries.

This was a “highlight” of the outcome in Rome, Brian O’Donnell, director of the Campaign for Nature, said in a statement.

Per the roadmap, countries will have to decide on criteria for the mechanism by COP17 next year in Armenia. By COP18, they will have to decide whether this will take the form of a new fund and, if so, make it operational by COP19 in 2030.

At the same time, the COP has tasked its expert subsidiary body to look into “opportunities for broadening the contributor base”, accommodating a key ask from developed countries.

This means including more countries, such as China, as formal biodiversity finance providers, according to Laetitia Pettinotti from development finance thinktank ODI. Pettinotti told Carbon Brief:

“Countries have agreed to look into the contributor base. But, actually, many developing countries already contribute biodiversity finance via their funding to multilateral entities – the GEF, WB [World Bank], UN agencies, etc. So part of this discussion will need to look at recognising those contributions.”

Resource mobilisation: from Cali to Rome

The Rome talks were expected to pick up where Cali left off – with an ambitious, but divisive, draft decision on resource mobilisation issued by Muhamad in the early hours of 2 November last year.

That document contained a proposal to establish a new global biodiversity fund under the COP’s governance, to be ready by COP30.

This had been a key demand of developing countries in the run-up to the previous talks in Montreal. Instead, the final nature deal for this decade – gavelled through at COP15 in a hurry – gave the world an interim fund with a mandate to operate only until 2030.

Without enough countries in the room to pass the decision in Cali, the fight for a new fund had to wait until COP16 resumed in Rome.

Between the Cali and Rome talks, Muhamad held regional consultations and bilateral meetings with countries and ministers from around the world in an effort to find agreement.

On 14 February, Muhamad released a “reflection note” laying out the state of play in the finance negotiations. In this, she discussed some of the “important differences” remaining between countries on the resource mobilisation draft and areas of “broad agreement” that emerged in her consultations.

Some of these disagreements, she said, were partly rooted in “different interpretations of terms used”. To address this, the note contained a glossary defining terms used within the finance texts.

Muhamad put forward a roadmap towards improving global biodiversity finance architecture, which, she said, countries “broadly support[ed]” at that stage.

In an updated note on 21 February, the president issued “textual suggestions” on the most contentious paragraphs of the resource mobilisation text.

At the opening plenary on 25 February, minister Muhamad said the discussions at this COP were “not technical decisions”, but rather “political decisions”. She questioned whether countries were able to “transcend…old and outdated” institutional structures and move towards something new.

Some countries broadly supported the president’s suggestions, but were clear that more discussions were needed. Others, such as India, were sceptical and favoured the explicit language in the draft text from Cali.

Most developing countries called for establishing a dedicated financial instrument at the Rome talks, opposed expanding the donor base and highlighted the need to “honour” existing financial commitments.

In turn, most developed countries wanted to improve – not replace – existing funding instruments and broaden the list of donor countries and funding sources. They also favoured a process leading up to COP19 that would not “prejudge the outcome”.

Fiji noted in the opening plenary that adopting a clear and comprehensive resource mobilisation strategy is “critical” to the success of the GBF. They added that the future process and roadmap must be “efficient and streamlined”, given the urgency of financing needs.

Informal consultations on resource mobilisation took place on the evening of 25 February. The next morning, Muhamad thanked delegates for the “very open and frank discussion” on their various positions on the text.

The negotiations moved slowly for most of the three days. A third of the morning plenary on 26 February, for example, was taken up by a back-and-forth over a request from the DRC to change the agenda.

A revised resource mobilisation document was released by the presidency on the evening of 26 February. Minutes later, countries were invited to give their thoughts on the significantly updated text in plenary.

Many expressed their surprise at the revisions and requested more time to review the text, which was only available in English as it had not yet been translated into the other five UN languages.

Egypt and the DRC’s request to give the African Group a few minutes to consult on the text was denied by Muhamad, with countries instead encouraged to discuss the text and present their concerns as regional groupings the next morning.

“This is becoming a precedent that a region cannot ask for regional consultations,” said Daniel Mukubi Kikuni of the DRC at the evening plenary, adding that the draft resembled Muhamad’s “informal” reflection note more than its predecessor that was negotiated by all countries in Cali. Kikuni added:

“[This document has been] deeply changed, transformed and modified. We cannot accept it as a foundational document for our discussion.”

Panama said that it was concerned by a “lack of ambition” in the revised document. Other countries, including Ivory Coast and Egypt, expressed concern that the pace of the document’s proposed roadmap was “missing urgency” and was too “process-heavy”, given that 2030 is five years away.

While the EU, Norway and the UK appreciated the text as a “balanced package” and said it was “very close to the landing zone”, they were caught off-guard by text that suggested “possible direct allocation” of funds to countries.

The next morning, another plenary took place for regional groupings to provide consolidated feedback on the updated draft. Several blocs and countries suggested alternative text, including a “compromise” proposal submitted by Brazil on behalf of BRICS countries and Zimbabwe articulating Africa’s position.

With the clock ticking and much to accomplish before midnight, Muhamad adjourned the plenary and asked up to five representatives from regions to work with her in a small group towards a consensus text to bring to the plenary.

After a six-hour closed door session, a new resource mobilisation non-paper emerged around 7pm on the final evening of talks.

The non-paper referred to the establishment of a “permanent arrangement for the financial mechanism”, mirroring text suggested by Brazil on behalf of BRICS countries earlier in the day. Instead of promising a new fund, the text said that the mechanism could be “entrusted to one or more entities, new, reformed or existing” – suggesting that a compromise had been struck between developed and developing countries

The non-paper had just one bracket in place (which, in UN documents, signals disagreement), stating that the final structure of the mechanism had to be “non-discriminatory”, which some delegates feared could potentially rule out certain funds that were limited by sanctions.

Bernadette Fischler Hooper, the head of international advocacy at WWF, told the press that this was a “make or break moment” to determine the levels of trust between countries, but that the text “showcased the high art of diplomacy”. She added:

“It doesn’t sound very exciting, but the fact that there will be [an instrument] from 2030 onwards is actually a huge step forward, because they haven’t managed to do that for the last five years. That was what nearly brought the COP15 in Montreal to fall.”

The presidency released a final revised document on resource mobilisation at 10:40pm, when the final plenary was already long-delayed.

This contained the same text as the non-paper, but with the final bracket removed. With no interventions, countries agreed and the final resource mobilisation text was gavelled through amid applause, cheers and tears in the plenary hall.

Minutes later, after interventions from the EU and Japan, Brazil cautioned against last-ditch changes to the closely related financial mechanism text, saying that “if we start to blow too close to [a castle of] cards, then everything starts to fall off”.

After a show of support from former COP-hosts Canada, the COP adopted the decision on the financial mechanism.

Juliette Landry of the Institute for Sustainable Development and International Relations (IDDRI) described the finance outcome to Carbon Brief as “a delicate balance” struck between “reluctant parties”. She added that countries had “agreed to lift polarised opposition” around a new fund in order to fix “systemic” gaps in existing biodiversity funding.

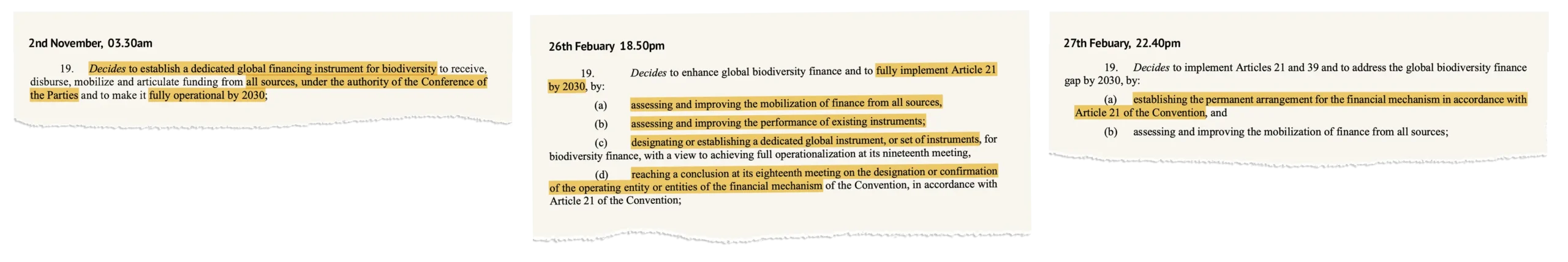

The figure below illustrates the development of language around a new financial instrument, in each iteration of the resource mobilisation text.

Successive iterations of language around the new financial instrument from Cali (left) to Rome (centre and right). Source: UN CBD (2024, 2025a, 2025b)

One of the drivers behind finance reform is that developing countries say they can struggle to access biodiversity finance. Ramson Karmushu from the International Indigenous Forum on Biodiversity told a press conference that submitting a funding proposal can be complicated and time-consuming.

He further noted that proposals which ask for data can be difficult for Indigenous peoples when the data is “in our minds, not in computers”.

Lim Li Ching from TWN, meanwhile, told Carbon Brief that despite the financial goals for 2025 and 2030 not being discussed in Rome, they remain “incredibly important”. She concluded:

“There’s still a long road ahead, but we live to fight another day.”

Global review

Another text that was adopted in Rome was on mechanisms for planning, monitoring, reporting and review (PMRR), including a global review of progress due to be conducted at COP17 in Armenia in 2026.

This is document outlines the schedule for how countries will assess their progress towards meeting the targets of the GBF in the coming years.

It is the first time in the history of biodiversity talks that countries have agreed to a text specifically on tracking their own progress. The groundwork for this was laid out in the GBF itself, which includes a section on “responsibility and transparency” from countries.

“Planning” refers to countries submitting national biodiversity strategies and action plans (NBSAPs). Countries were meant to submit new NBSAPs by October 2024, but, so far, three-quarters of countries have yet to do so.

“Monitoring” refers to countries using indicators set out in the monitoring framework (see below) to assess their progress towards meeting biodiversity targets.

“Reporting” refers to the need for countries to produce national reports detailing this progress by early 2026. Shortly after this, a “global report” will be produced, assessing NBSAPs and national targets to track whether countries are on track for the targets of the GBF.

“Review” refers to a global review of progress, which is due to take place at COP17.

In Cali, countries managed to produce a bracket-free version of the PMRR text.

At the time, observers said it was generally positive that nations had managed to agree to a way for tracking their own progress, but noted that the text lacked a clear follow-up procedure to ensure countries increase their efforts accordingly after the global review.

Some also lamented the lack of opportunities for all stakeholders, including civil society, to participate in the PMRR process.

Despite countries finalising the text, it was not adopted at the end of the Cali talks. This is because it was scheduled for adoption after the texts on finance, which countries ultimately failed to find consensus on.

In Rome, the CBD secretariat presented a new version of the PMRR text during a plenary on 25 February. This included an adjusted timeline reflecting that work towards the report and review will start following the end of the resumed talks, rather than December 2024 as previously set out.

A representative of the secretariat said the timeline for ensuring all the work is completed is now extremely “tight”, but still achievable.

Many nations expressed their support for the PMRR text and urged other countries to accept it without making any further changes.

However, Russia and Zimbabwe both raised concerns with small details of the text. COP16 president Susana Muhamad said she would consult privately with parties that were not yet happy to accept the PMRR text.

In plenary on the following day, countries turned to the PMRR text again.

At this point, Zimbabwe suggested adding in a new footnote.

Zimbabwe’s specific concern was around a section of the text that invites non-state actors, such as NGOs and companies, to voluntarily contribute what they are doing to meet the targets of the GBF to the CBD’s online portal.

Zimbabwe called for a footnote noting that these submissions shall be subject to the consent and approval of the country that the non-state actor is based in.

This call was backed by Cameroon, Egypt, Indonesia, Russia, Ghana, the Ivory Coast, the DRC and Russia, according to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin. It was opposed by the European Union and Norway.

Explaining the possible motivations of including such a footnote in the text, one observer told Carbon Brief that, from a “positive” perspective, it might allow countries to block “greenwashing” from companies, adding:

“If you want to be a little bit more cynical about it, it gives countries an opportunity to be less open to hearing from voices they don’t necessarily want to hear criticism from.”

The next day, all nations agreed to include this new footnote – leaving no outstanding issues.

During the summit’s final plenary session, the PMRR text was gavelled through with no objections.

Monitoring framework

The monitoring framework is a document that lays out how countries will measure their progress towards the individual targets of the GBF, using four types of indicators: headline; binary; component; and complementary:

- Headline indicators: used to measure quantifiable progress towards a given target, such as the pledge to restore 30% of degraded ecosystems by 2030.

- Binary indicators: yes-or-no questions used to evaluate progress towards more qualitative goals, such as engagement with women and youth.

- Component indicators: used to measure progress towards specific parts of the targets of the GBF.

- Complementary indicators: used to measure progress towards related goals that are not made explicit in the GBF itself.

While headline and binary indicators are mandatory for countries to report, component and complementary indicators are optional.

During the Cali summit, Lim Li Lin, a senior legal and environment advisor at Third World Network, told Carbon Brief:

“Everyone’s doing a juggle, right? We want the good ones to go in the mandatory and we want the bad ones to go in the complementary, if we can’t get rid of them. And everyone’s doing the same thing from their own interest and perspective.”

Going into Rome, the entire monitoring framework was contained in brackets – meaning, in UN parlance, that the text had not been agreed. This was a result of manoeuvring by the DRC during Cali to ensure that the fate of the framework was tied to that of the finance deal.

Within the text, however, were two outstanding areas of disagreement: one on the indicator for target 7 on reducing harm from pollution, including pesticides; and one on the indicator for target 16 on enabling sustainable consumption.

On pesticide usage, parties were split between requiring countries to report their “pesticide environment concentration” and the “aggregated total applied toxicity”. The former was adopted as part of the monitoring framework during COP15, while the latter was proposed by the technical expert group that met in between COP15 and COP16.

In Colombia, parties converged on allowing both methods to be used as headline indicators, but could not reach agreement on an accompanying footnote explaining why both were being listed and how parties had to report.

In the plenary on 25 February, the UK proposed a compromise footnote text allowing parties to choose which headline indicator to use.

Although some countries suggested prioritising one indicator over the other, the proposal was approved “in the spirit of compromise”, Earth Negotiations Bulletin reported. A separate footnote explained that the FAO is working to “further develop and test the aggregated total applied toxicity headline indicator”.

On sustainable use, countries were split over non-binding component indicators on “global environmental impacts of consumption” and “ecological footprint”. Brazil suggested removing the indicator on global impacts of consumption, “noting that it cannot be validated at the national level”, according to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin.

Discussions on the sustainable-use indicators spilled over into the second day of the Rome talks. The compromise proposal, brought forward by the EU, was to remove the indicator on global environmental impacts of consumption, but retain the indicator on ecological footprint, along with a footnote on methodology and the availability of data.

The updated text was accepted with no objections during the final plenary on 27 February.

Cooperation with other conventions

A text highlighting the links between the Convention on Biological Diversity and other organisations was not discussed until the final hours of the Rome talks.

The text was not viewed as contentious near the start of the three-day summit. Amid the trickier negotiations, it was pushed down on the agenda until a dramatic finale in which the text was approved, un-approved and then gavelled through with last-minute amendments.

The Cook Islands and other countries expressed disappointment with the final tweaks, but said they agreed in order to get a deal over the line.

The agreement recognised, among other things, the ties between the three Rio Conventions – the UN treaties agreed in 1992 under which countries meet separately to negotiate on climate change, biodiversity and desertification.

The final COP16 cooperation decision “invites” countries to “strengthen synergies and cooperation in the implementation of each convention, in accordance with national circumstances and priorities”.

The presidency released a new version of the draft text on 27 February. Among the changes in this text from the previous December draft was the removal of two bracketed paragraphs stressing the importance of future collaboration between the CBD and the global treaty on governing the sustainable use and conservation of biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (“BBNJ”, or the “High Seas Treaty”).

In the closing plenary, Iceland opposed the deletion of these “two very important paragraphs” referring to the BBNJ treaty “without any discussion”. Russia, supported later by Brazil, stood by the deletion, adding that they were “not in a position to bring [those paragraphs] back”.

The negotiations on this draft went on until close to midnight on 27 February when Muhamad said, much like “Cinderella”, they were running out of time. (The UN translators were supposed to work only until midnight, although they ended up staying through the end of the plenary.) In light of this constraint – and amid disagreement on BBNJ’s inclusion – Muhamad withdrew discussions on the text, pushing its agreement to COP17.

However, Switzerland, the EU and Zimbabwe intervened to push for the approval of the “really important” text. Iceland withdrew its intervention on BBNJ and Muhamad moved to adopt the document.

But Russia noted that the president had not addressed their proposal to delete paragraph 20, which discussed collaboration with the future UN plastic pollution treaty on the pollution-reducing target of the GBF.

After indications of support from India, Switzerland and the EU, the text was adopted by the plenary – now with paragraph 20 removed.

But it did not end there. Argentina took to the floor to suggest further amendments in three parts of the text. Muhamad said this interjection was too late, but Argentina argued that they requested to speak before the gavel fell.

Brazil backed Argentina and recalled the ending of COP15 in Montreal when the final GBF was gavelled through, despite objections by the DRC.

Brazil said this is a “wound that has not healed” for developing countries and that, while they disagree with Argentina’s position, they support their right to speak up.

Muhamad said she did not see Argentina’s request before dropping the gavel, but offered to postpone cooperation negotiations, if countries agreed. The EU did not want this and suggested deleting the paragraphs Argentina took issue with.

These included paragraph 7, referring to FAO work on a draft action plan on biodiversity for food and nutrition, and paragraph 12, discussing the rights of nature and other knowledge systems.

Georgia and Zimbabwe intervened to say that, while unfortunate to remove this text, they agreed with the EU. After more back-and-forth, the text was once again gavelled through, with the proposed amendments.

The final text also referenced outcomes from the UN Environment Programme, the World Health Organization and others.

Around the COP

The Rome COP was a more low-key affair than other summits. There were no side events, parallel meetings or working groups – just plenary sessions, followed by informal evening meetings between countries.

Around 1,000 people attended the talks, compared to 14,000 in Cali.

In the run-up to the summit, Muhamad’s COP16 presidency was called into question after she announced her resignation as Colombia’s environment minister on 9 February. The move was in protest of a controversial cabinet appointment by president Gustavo Petro, Reuters reported.

Muhamad asked Petro in her resignation letter to let her remain in the position until 3 March to allow her to conclude the COP16 talks, Climate Home News said.

In the end, she presided over the Rome talks, telling Carbon Brief in a press conference that she continued to have full capacity as environment minister.

Environment ministers and vice-ministers from Canada, Colombia, DRC, Guinea-Bissau, Madagascar, Peru, Armenia, Fiji, Germany, Suriname confirmed they would attend the talks.

The Cali Fund – a mechanism where companies can contribute money if they use digitally accessed genetic resources from nature in their products – was officially launched at a press conference in Rome on Tuesday 25 February.

The fund – which was one of the major successes of the Cali talks – is currently empty.

A number of companies are already “actively considering” paying into the fund, Astrid Schomaker said at the launch of the fund. (She would not name specific companies when asked by Carbon Brief.)

The CBD chief said the convention has actively contacted companies and business groups to discuss paying into the fund. Muhamad added at the press conference that the fund is not for “charity from the companies”, but “fair payment for the use of global biodiversity”.

The resumed nature talks came at a volatile time in climate and nature diplomacy. The new administration of the US – a major donor to climate and nature funds – caused turmoil and uncertainty across the globe when Donald Trump announced moves to shut down the US Agency for International Development (USAid).

The UN confirmed to Carbon Brief that the US did not send a delegation to Rome.

This was a first for biodiversity talks. Despite not being party to the CBD, US officials usually still attend talks to contribute to negotiations as observers.

At the opening plenary of the talks, Susana Muhamad spoke about the need for agreement amid the current “polarised, fragmented, divisive geopolitical landscape”. She added:

“We have an important responsibility here in Rome. In 2025, we can send a light globally and be able to say that still, even with our differences, even with our tensions…we are able to collaboratively work together for something that transcends our own interests.”

At the sidelines of the talks, the UK made a snap decision to belatedly publish its NBSAP, Carbon Brief reported.

Some three-quarters of nations still have not published their NBSAPs, four months after the UN deadline.

On the summit’s final day, youth activists held a demonstration in the corridors of the conference, in protest of their lack of opportunities to speak at the event.

The post COP16: Key outcomes agreed at the resumed UN biodiversity conference in Rome appeared first on Carbon Brief.

COP16: Key outcomes agreed at the resumed UN biodiversity conference in Rome

Climate Change

Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding

The Lincolnshire constituency held by Richard Tice, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of the hard-right Reform party, has been pledged at least £55m in government funding for flood defences since 2024.

This investment in Boston and Skegness is the second-largest sum for a single constituency from a £1.4bn flood-defence fund for England, Carbon Brief analysis shows.

Flooding is becoming more likely and more extreme in the UK due to climate change.

Yet, for years, governments have failed to spend enough on flood defences to protect people, properties and infrastructure.

The £1.4bn fund is part of the current Labour government’s wider pledge to invest a “record” £7.9bn over a decade on protecting hundreds of thousands of homes and businesses from flooding.

As MP for one of England’s most flood-prone regions, Tice has called for more investment in flood defences, stating that “we cannot afford to ‘surrender the fens’ to the sea”.

He is also one of Reform’s most vocal opponents of climate action and what he calls “net stupid zero”. He denies the scientific consensus on climate change and has claimed, falsely and without evidence, that scientists are “lying”.

Flood defences

Last year, the government said it would invest £2.65bn on flood and coastal erosion risk management (FCERM) schemes in England between April 2024 and March 2026.

This money was intended to protect 66,500 properties from flooding. It is part of a decade-long Labour government plan to spend more than £7.9bn on flood defences.

There has been a consistent shortfall in maintaining England’s flood defences, with the Environment Agency expecting to protect fewer properties by 2027 than it had initially planned.

The Climate Change Committee (CCC) has attributed this to rising costs, backlogs from previous governments and a lack of capacity. It also points to the strain from “more frequent and severe” weather events, such as storms in recent years that have been amplified by climate change.

However, the CCC also said last year that, if the 2024-26 spending programme is delivered, it would be “slightly closer to the track” of the Environment Agency targets out to 2027.

The government has released constituency-level data on which schemes in England it plans to fund, covering £1.4bn of the 2024-26 investment. The other half of the FCERM spending covers additional measures, from repairing existing defences to advising local authorities.

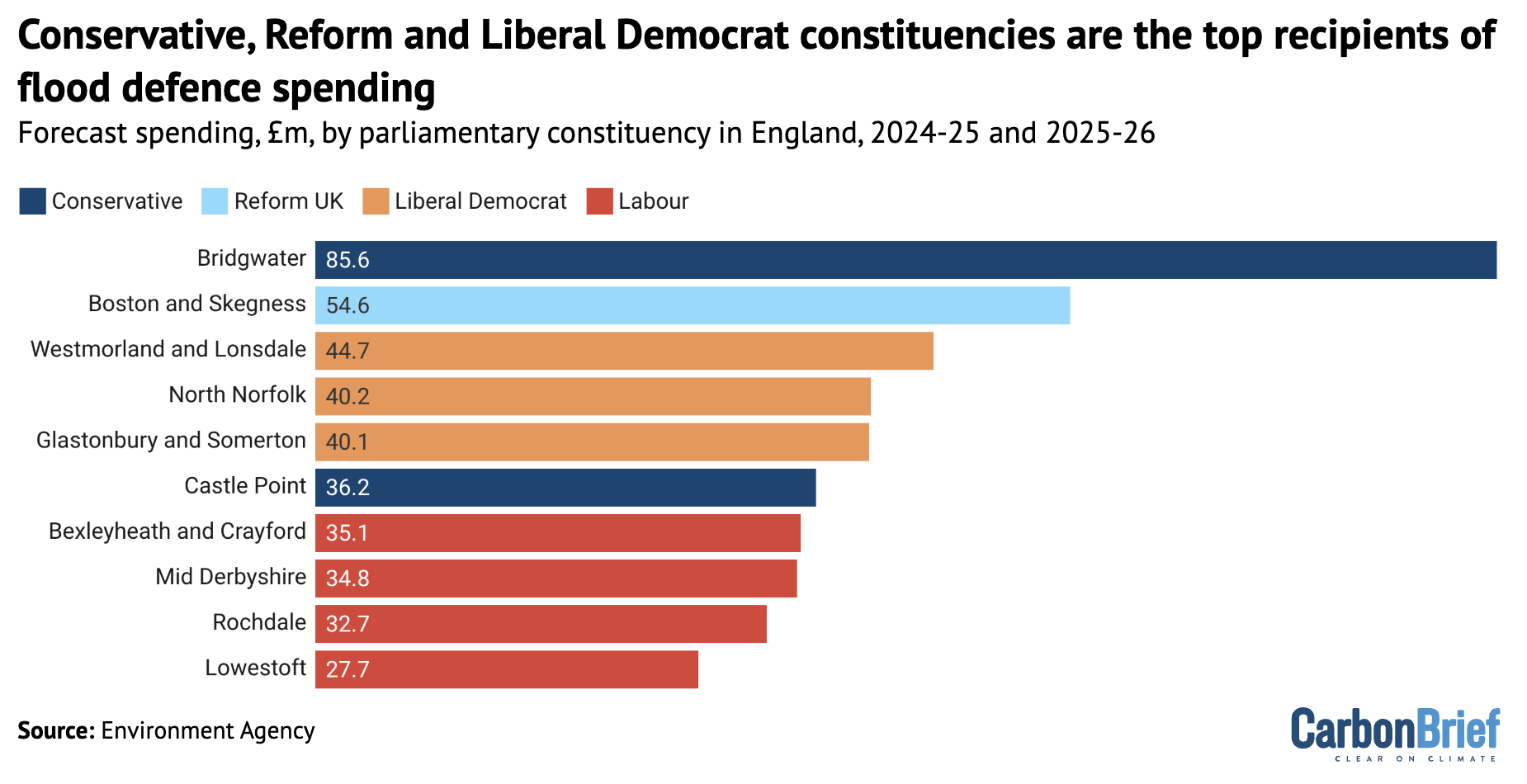

The map below shows the distribution of spending on FCERM schemes in England over the past two years, highlighting the constituency of Richard Tice.

By far the largest sum of money – £85.6m in total – has been committed to a tidal barrier and various other defences in the Somerset constituency of Bridgwater, the seat of Conservative MP Ashley Fox.

Over the first months of 2026, the south-west region has faced significant flooding and Fox has called for more support from the government, citing “climate patterns shifting and rainfall intensifying”.

He has also backed his party’s position that “the 2050 net-zero target is impossible” and called for more fossil-fuel extraction in the North Sea.

Tice’s east-coast constituency of Boston and Skegness, which is highly vulnerable to flooding from both rivers and the sea, is set to receive £55m. Among the supported projects are beach defences from Saltfleet to Gibraltar Point and upgrades to pumping stations.

Overall, Boston and Skegness has the second-largest portion of flood-defence funding, as the chart below shows. Constituencies with Conservative and Liberal Democrat MPs occupied the other top positions.

Overall, despite Labour MPs occupying 347 out of England’s 543 constituencies – nearly two-thirds of the total – more than half of the flood-defence funding was distributed to constituencies with non-Labour MPs. This reflects the flood risk in coastal and rural areas that are not traditional Labour strongholds.

Reform funding

While Reform has just eight MPs, representing 1% of the population, its constituencies have been assigned 4% of the flood-defence funding for England.

Nearly all of this money was for Tice’s constituency, although party leader Nigel Farage’s coastal Clacton seat in Kent received £2m.

Reform UK is committed to “scrapping net-zero” and its leadership has expressed firmly climate-sceptic views.

Much has been made of the disconnect between the party’s climate policies and the threat climate change poses to its voters. Various analyses have shown the flood risk in Reform-dominated areas, particularly Lincolnshire.

Tice has rejected climate science, advocated for fossil-fuel production and criticised Environment Agency flood-defence activities. Yet, he has also called for more investment in flood defences, stating that “we cannot afford to ‘surrender the fens’ to the sea”.

This may reflect Tice’s broader approach to climate change. In a 2024 interview with LBC, he said:

“Where you’ve got concerns about sea level defences and sea level rise, guess what? A bit of steel, a bit of cement, some aggregate…and you build some concrete sea level defences. That’s how you deal with rising sea levels.”

While climate adaptation is viewed as vital in a warming world, there are limits on how much societies can adapt and adaptation costs will continue to increase as emissions rise.

The post Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: Constituency of Reform’s climate-sceptic Richard Tice gets £55m flood funding

Climate Change

US Government Is Accelerating Coral Reef Collapse, Scientists Warn

Proposed Endangered Species Act rollbacks and military expansions are leaving the Pacific’s most diverse coral reefs legally defenseless.

Ritidian Point, at the northern tip of Guam, is home to an ancient limestone forest with panoramic vistas of warm Pacific waters. Stand here in early spring and you might just be lucky enough to witness a breaching humpback whale as they migrate past. But listen and you’ll be struck by the cacophony of the island’s live-fire testing range.

US Government Is Accelerating Coral Reef Collapse, Scientists Warn

Climate Change

Satellites Reveal New Climate Threat to Emperor Penguins

Ice loss in the Antarctic Ocean may be killing the sea birds during their molting season.

Each year for millennia, emperor penguins have molted on coastal sea ice that remained stable until late summer—a haven during a span of several weeks when it’s dangerous for the mostly aquatic birds to enter the ocean to feed because they are regrowing their waterproof feathers.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits