The first-ever international conference on the contentious topic of “overshoot” was held last week in a palace in the small town of Laxenburg in Austria.

The three-day conference brought together nearly 200 researchers and legal experts to discuss future temperature pathways where the Paris Agreement’s “aspirational” target to limit global warming to 1.5C is met “from above, rather than below”.

Overshoot pathways are those which exceed the 1.5C limit – before being brought back down again through techniques that remove carbon from the atmosphere.

The conference explored both the feasibility of overshoot pathways and the legal frameworks that could help deliver them.

Researchers also discussed the potential consequences of a potential rise – and then fall – of global temperatures on climate action, society and the Earth’s climate systems.

Speaking during a plenary session, Prof Joeri Rogelj, a professor of climate science and policy at Imperial College London, said that “moving into a world where we exceed 1.5C and have to manage overshoot” was an exercise in “managing failure”.

He said that it was “essential” that this failure was acknowledged, explaining that this would help set out the need to “minimise and manage” the situation and clarify the implications for “near-term action” and “long-term [temperature] reversal”.

Below, Carbon Brief draws together some of the key talking points, new research and discussions that emerged from the event.

- Defining overshoot

- Mitigation ambition and 1.5C viability

- Carbon removal

- Impacts of overshoot

- Adaptation

- Legal implications and loss and damage

- Communication challenges and next steps

Defining overshoot

The study of temperature overshoot has grown in recent years as the prospects of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5C have dwindled.

Conference organiser Dr Carl-Friedrich Schleussner – a senior research scholar at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) – explained the event was designed to bring together different research communities working on a “new field of science”.

He told Carbon Brief:

“If we look at [overshoot] in isolation, we may miss important parts of the bigger picture. That’s why we also set out the conference with very broad themes and a very interdisciplinary approach.”

The conference was split between eight conference streams: mitigation ambition; carbon dioxide removal (CDR); Earth system responses; climate impacts; tipping points; adaptation; loss and damage; and legal implications.

There was also a focus on how to communicate the concept of overshoot.

In simple English, “overshoot” means to go past or beyond a limit. But, in climate science, the term implies both a failure to meet a target – as well as subsequent action to correct that failure.

Today, the term is most often deployed to describe future temperature trajectories that exceed the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C limit – and then come back down.

(In the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC’s) fifth assessment cycle, completed in 2014, the term was used to describe a potential rise and then fall of CO2 concentrations above levels recommended to meet long-term climate goals. A recent “conceptual” review of overshoot noted this was because, at the time, CO2 concentrations were the key metric used to contextualise emissions reductions).

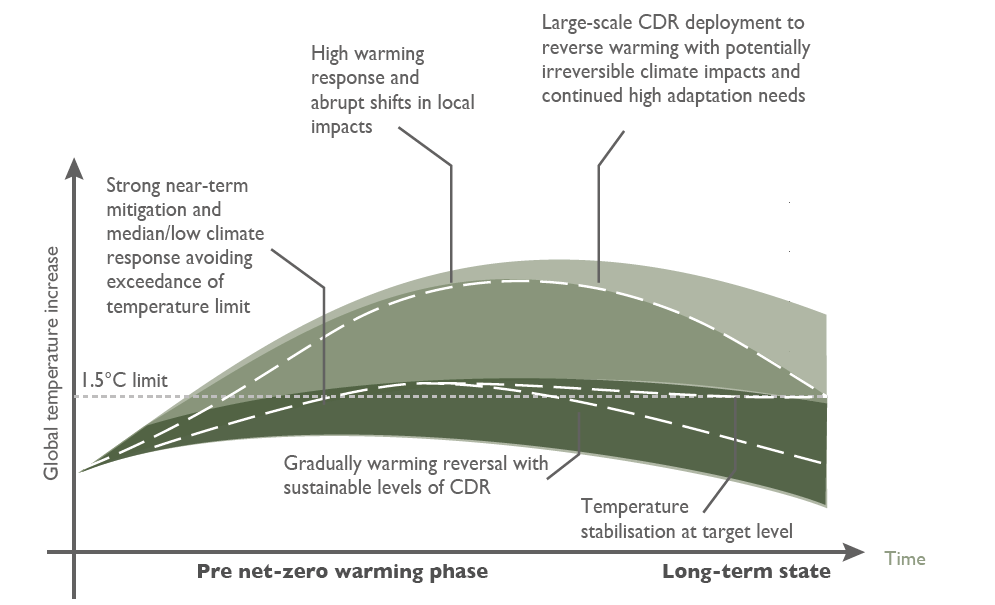

The plot below provides an illustration of three overshoot pathways. The most pronounced pathway sees global temperatures rise significantly above the 1.5C limit – before eventually falling back down again as carbon dioxide is pulled from the atmosphere at scale.

In the second and third pathways, global temperature rise breaches the limit by a smaller margin, before either falling enough just to stabilise around 1.5C, or dropping more dramatically due to larger-scale carbon removals.

In an opening address to delegates, Prof Jim Skea, who is the current chair of the IPCC, acknowledged the scientific interpretation of overshoot was not intuitive to non-experts.

“The IPCC has mainly used two words in relation to overshoot – “exceeding” and “limiting”. To a lay person, these can sound like opposites. Yet we know that a single emissions pathway can both exceed 1.5C in the near term and limit warming to 1.5C in the long term.”

Noting that different research communities were using the term differently, Skea urged researchers to be precise with terminology and stick to the IPCC’s definition of overshoot:

“We should give some thought to communication and keep this as simple as possible. When I look at texts, I hear more poetic words like “surpassing” and “breaching”. I would urge you to keep the range of terms as small as possible and make sure that we’re absolutely using them consistently.”

In the glossary for its latest assessment cycle, AR6, the IPCC defines “overshoot” pathways as follows:

IIASA’s Schleussner stressed that not all pathways that go beyond 1.5C qualify as overshoot pathways:

“The most important understanding is that overshoot is not any pathway that exceeds 1.5C. An overshoot pathway is specific to this being a period of exceedance. It is going to come back down below 1.5C.”

Mitigation ambition and 1.5C viability

Perhaps the most prominent topic during the conference was the implications of overshoot for global ambition to cut carbon emissions and the viability of the 1.5C limit.

Opening the conference, IIASA director general Prof Hans Joachim Schellnhuber shared his personal view that “1.5C is dead, 2C is in agony and 3C is looming”.

In a pre-recorded keynote speech, Ralph Regenvanu, Vanuatu’s minister for climate change, called for a rejection of the “normalisation of overshoot” and argued that “we must treat 1.5C as the absolute limit that it is” and avoid backsliding. He added:

“Minimising peak warming must be our lodestar, because every tenth of a degree matters.”

Prof Skea opened his keynote with some theology:

“I’m going to start with the prayer of St Augustine as he struggled with his youthful longings: ‘Lord grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.’ And it does seem that this is the way that the world as a whole is thinking about 1.5C: ‘Lord, limit warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, but not yet.’”

Referencing the “lodestar” mentioned by Regenvanu, Skea warned that it is light years away and, “unless we act with a sense of urgency, [1.5C is] likely to remain just as remote”.

Speaking to Carbon Brief on the sidelines of the conference, Skea added:

“We are almost certain to exceed 1.5C and the viability of 1.5C is now much more referring to the long-term potential to limit it through overshoot.”

Schleussner told Carbon Brief that the framing of 1.5C in the conference is “one that further solidifies 1.5C as the long-term limit and, therefore, provides a backstop against the idea of reducing or backsliding on targets”.

If warming is going to surpass 1.5C, the next question is when temperatures are going to be brought back down again, Schleussner added, noting that there has been no “direct” guidance on this from climate policy:

“The [Paris Agreement’s] obligation to “pursue efforts” [to limit global temperature rise by 1.5C] points to doing it as fast as possible. Scientifically, we can determine what this means – and that would be this century. But there’s no clear language that gives you a specific date. It needs to be a period of overshoot – that is clear – and it should be as short as possible.”

In a parallel session on the “highest possible mitigation ambition under overshoot”, Prof Joeri Rogelj, professor of climate science and policy at Imperial College London, outlined how the recent ruling from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) provides guidance to countries on the level of ambition in their climate pledges under the Paris Agreement, known as “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs). He explained:

“[The ruling] highlights that the level of NDC ambition is not purely discretionary to a state and that every state must do its utmost to ensure its NDC reflects the highest possible ambition to meet the Paris Agreement long-term temperature goal.”

Rogelj presented some research – due to be published in the journal Environmental Research Letters – on translating the ICJ’s guidance “into a framework that can help us to assess whether an NDC indeed is following a standard of conduct that can represent the highest level of ambition”. He showed some initial results on how the first two rounds of NDCs measure up against three “pillars” covering domestic, international and implementation considerations.

In the same session, Prof Oliver Geden, senior fellow and head of the climate policy and politics research cluster at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs and vice-chair of IPCC Working Group III, warned that the concept of returning temperatures back down to 1.5C after an overshoot is “not a political project yet”.

He explained that there is “no shared understanding that, actually, the world is aiming for net-negative”, where emissions cuts and CDR together mean that more carbon is being taken out of the atmosphere than is being added. This is necessary to achieve a decline in global temperatures after surpassing 1.5C.

This lack of understanding includes developed countries, which “you would probably expect to be the frontrunners”, Geden said, noting that Denmark is the “only developed country that has a quantified net-negative target” of emission reductions of 110% in 2050, compared to 1990 levels. (Finland also has a net-negative target, while Germany announced its intention to set one last year. In addition, a few small global-south countries, such as Panama, Suriname and Bhutan, have already achieved net-negative.)

Geden pondered whether developed countries are a “little bit wary to commit to going to net-negative territory because they fear that once they say -110%, some countries will immediately demand -130% or -150%” to pay back a larger carbon debt.

Carbon removal

To achieve a decline in global temperatures after an initial breach of 1.5C would require the world to reach net-negative emissions overall.

There is a wide range of potential techniques for removing CO2 from the atmosphere, such as afforestation, direct air capture and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). Captured carbon must be locked away indefinitely in order to be effective at reducing global temperatures.

However, despite its importance in achieving net-negative emissions, there are “huge knowledge gaps around overshoot and carbon dioxide removal”, Prof Skea told Carbon Brief. He continued:

“As it’s very clear from the themes of this conference, we don’t altogether understand how the Earth would react in taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. We don’t understand the nature of the irreversibilities. And we don’t understand the effectiveness of CDR techniques, which might themselves be influenced by the level of global warming, plus all the equity and sustainability issues surrounding using CDR techniques.”

Skea notes that the seventh assessment cycle of the IPCC, which is just getting underway, will “start to fill these knowledge gaps without prejudging what the appropriate policy response should be”.

Prof Nebojsa Nakicenovic, an IIASA distinguished emeritus research scholar, told Carbon Brief that his “major concern” was whether there would be an “asymmetry” in how the climate would respond to large-scale carbon removal, compared to its response to carbon emissions.

In other words, he explained, would global temperatures respond to carbon removal “on the way down” in the same way they did “on the way up” to the world’s carbon emissions.

Nakicenovic noted that overshoot requires a change in focus to approaching the 1.5C limit “from above, rather than below”.

Schleussner made a similar point to Carbon Brief:

“We may fail to pursue [1.5C] from below, but it doesn’t relieve us from the obligation to then pursue it from above. I think that’s also a key message and a very strong overarching message that’s going to come out from the conference that we see…that pursuing an overshoot and then decline trajectory is both an obligation, but it also is well rooted in science.”

Reporting back to the plenary from one of the parallel sessions on CDR, Dr Matthew Gidden, deputy director of the Joint Global Change Research Institute at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, also noted another element of changing focus:

“When we’re talking about overshoot, we have become used to, in many cases, talking about what a net-zero world looks like. And that’s not a world of overshoot. That’s a world of not returning from a peak. And so communicating instead about a net-negative world is something that we could likely be shifting to in terms of how we’re communicating our science and the impacts that are coming out of it.”

On the need for both CDR and emissions cuts, Gidden noted that the discussions in his session emphasised that “CDR should not be at the cost of mitigation ambition”. But, he added, there is still the question of how “we talk about emission reductions needed today, but also likely dependence on CDR in the future”.

In a different parallel session, Prof Geden also made a similar point, noting that “we have to shift CDR from being seen as a barrier to ambition to an enabler of even higher ambition, but not doing that by betting on ever more CDR”.

Among the research presented in the parallel sessions on CDR was a recent study by Dr Jay Fuhrman from the JGCRI on the regional differences in capacity to deploy large-scale carbon removal. Ruben Prütz, from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, presented on the risks to biodiversity from large-scale land-based CDR, which – in some cases – could have a larger impact than warming itself.

In another talk, the University of Oxford’s Dr Rupert Stuart-Smith explored how individual countries are “depending very heavily on [carbon] removals to meet their climate targets”. Stuart-Smith was a co-author on an “initial commentary” on the legal limits of CDR, published in 2023. This has been followed up with a “much more detailed legal analysis”, which should be published “very soon”, he added.

Impacts of overshoot

Since the Paris Agreement and the call for the IPCC to produce a special report on 1.5C, research into the impacts of warming at the aspirational target has become commonplace.

Similarly, there is an abundance of research into the potential impacts at other thresholds, such as 2C, 3C and beyond.

However, there is comparatively little research into how impacts are affected by overshoot.

The conference included talks on some published research into overshoot, such as the chances of irreversible glacier loss and lasting impacts to water resources. There were also talks on work that is yet to be formally published, such as the risks of triggering interacting tipping points under overshoot.

Speaking in a morning plenary, Prof Debra Roberts, a coordinating lead author on the IPCC’s forthcoming special report on climate change and cities and a former co-chair of Working Group II, highlighted the need to consider the implications of different durations and peak temperatures of overshoot.

For example, she explained, it is “important to know” whether the impacts of “overshoot for 10 years at 0.2C above 1.5C are the same as 20 years at 0.1C of overshoot”.

Discussions during the conference noted that the answer may be different depending on the type of impact. For heat extremes, the peak temperature may be the key factor, while the length of overshoot will be more relevant for cumulative impacts that build up over time, such as sea level rise.

Similarly, if warming is brought back down to 1.5C after overshoot, what happens next is also significant – whether global temperature is stabilised or net-negative emissions continue and warming declines further. Prof Schleussner told Carbon Brief:

“For example, with coastal adaptation to sea level rise, the question of how fast and how far we bring temperatures back down again will be decisive in terms of the long-term outlook. Knowing that if you stabilise that around 1.5C, we might commit two metres of sea level rise, right? So, the question of how far we can and want to go back down again is decisive for a long-term perspective.”

One of the eight themes of the conference centred specifically on the reversibility or irreversibility of climate impacts.

In his opening speech, Vanuatu’s Ralph Regenvanu warned that “overshooting 1.5C isn’t a temporary mistake, it is a catalyst for inescapable, irreversible harm”. He continued:

“No level of finance can pull back the sea in our lifetimes or our children’s. There is no rewind button on a melted glacier. There is no time machine for an extinct species. Once we cross these tipping points, no amount of later ‘cooling’ can restore our sacred reefs, it cannot regrow the ice that already vanished and it cannot bring back the species or the cultures erased by the rising tides.”

As an example of a “deeply, deeply irreversible” impact, Dr Samuel Lüthi, a postdoctoral research fellow in the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine at the University of Bern, presented on how overshoot could affect heat-related mortality.

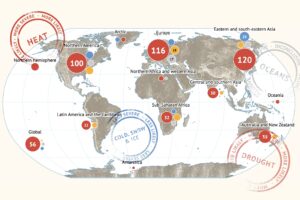

Using mortality data from 850 locations across the world, Lüthi showed how projections under a pathway where warming overshoots 1.5C by 0.1-0.3C, before returning to 1.5C by 2100 has 15% more heat-related deaths in the 21st century than a pathway with less than 0.1C of overshoot.

His findings also suggested that “10 years of 1.6C is very similar [in terms of impacts] to five years of 1.7C”.

Extreme heat also featured in a talk by Dr Yi-Ling Hwong, a research scholar at IIASA, on the implications of using solar geoengineering to reduce peak temperatures during overshoot.

She showed that a world where a return to 1.5C had been achieved through geoengineering would see different impacts from a world where 1.5C was reached through cutting emissions. For example, in her modelling study, while geoengineering restores rainfall levels for some regions in the global north, significant drying “is observed in many regions in the global south”.

Similarly, a world geoengineered to 1.5C would see extreme nighttime heat in some tropical regions that is more severe than in a 2C world with no geoengineering, Hwong added.

In short, she said, “this implies the risk of creating winners and losers” under solar geoengineering and “raises concerns about equity and accountability that need to be considered”.

After describing how overshoot features in the outlines of the forthcoming AR7 reports in his opening speech, Prof Skea told Carbon Brief that he expects a “surge of papers” on overshoot in time to be included.

But it was important to emphasise that a “lot of the science that people have been carrying out is relevant within or without an overshoot”, he added:

“At points in the future, we are not going to know whether we’re in an overshoot world or just a high-emissions world, for example. So a lot of the climate research that’s been done is relevant regardless of overshoot. But overshoot is a new kind of dimension because of this issue of focus on 1.5C and concerns about its viability.”

Adaptation

The implications of overshoot temperature pathways for efforts to prepare cities, countries and citizens for the impacts of climate change remains an under-researched field.

Speaking in a plenary, Prof Kristie Ebi – a professor at the University of Washington’s Center for Health and the Global Environment – described research into adaptation and overshoot as “nascent”. However, she stressed that preparing society for the impacts associated with overshoot pathways was as important as bringing down emissions.

She told Carbon Brief that there were “all kinds of questions” about how to approach “effective” adaptation under an overshoot pathway, explaining:

“At the moment, adaptation is primarily assuming a continual increase in global mean surface temperature. If there is going to be a peak – and, of course, we don’t know what that peak is – then how do you start planning? Do you change your planning? There are places, for instance when thinking about hard infrastructure, [where overshoot] may result in a change in your plan.”

IIASA’s Schleussner told Carbon Brief that the scientific community was only just “beginning to appreciate” the need to understand and “quantify” the implications of different overshoot pathways on adaptation.

In a parallel session, Dr Elisabeth Gilmore, associate professor in environmental engineering and public policy at Carleton University in Canada, made the case for overshoot modelling pathways to take greater account of political considerations.

“Not just, but especially, in situations of overshoot, we need to start thinking about this as much as a physical process as a socio-political process…If we don’t do this, we are really missing out on some key uncertainties.”

Current scenarios used in climate research – including the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and Representative Concentration Pathways – are “a bit quiet” when it comes to thinking about governance, institutions and peace and conflict, Gilmore said. She added:

“Political institutions, legitimacy and social cohesion continue to shift over time and this is really going to shape how much we can mitigate, how much we adapt and especially how we would recover when adding in the dimension of overshoot.”

Gilmore argued that, from a social perspective, adaptation needs are greatest “before the peak” of temperature rise – because this is when society can build the resilience to “get to the other side”. She said:

“Orthodoxy in adaptation [research] that you always want to plan for the worst [in the context of adaptation, peak temperature rise]… But we don’t really know what this peak is going to be – and we know that the politics and the social systems are much more messy.”

Dr Marta Mastropietro, a researcher at Politecnico di Milano in Italy, presented the preliminary results of a study that used emulators – simple climate models – to explore how human development might be impacted under low, medium and high overshoot pathways.

Mastropietro noted how, under all overshoot scenarios studied, both the drop to the human development index (HDI) – an index which incorporates health, knowledge and standard of living – and uncertainty increases as the peak temperature increases.

However, she said “the most important takeaway” from the preliminary results was around society’s constrained ability to recover from damage.

“This percentage of damages that are absorbed is always less than 50%. So, even in the most optimistic scenarios of overshoot, we will not be able to reabsorb these damages, not even half of them. And this is considering a damage function which does not consider irreversible impacts like sea level rise.”

Meanwhile, Dr Inês Gomes Marques from the University of Lisboa in Portugal, shared the results of an as-yet-unpublished study investigating whether the Lisbon metropolitan area holds enough public spaces to offer heatwave relief to the population under overshoot scenarios. The 1,900 “climate refugia” counted by researchers included schools, museums and churches.

Marques noted that most of the population were found to be within one kilometre of a “climate refugia” – but noted that “nuances” would need to be added to the analysis, including a function which considers the limited mobility of older citizens.

She explained that the researchers were aiming to “establish a framework” for this type of analysis that would be relevant to both the science community and municipalities tasked with adaptation. She added:

“The main point is that we need to think about this now, because we will face some big problems if we don’t”.

Legal implications and loss and damage

Significant attention was given throughout the conference to the legal considerations of the breach of – and impetus to return to – the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C warming limit.

This included discussions about how the international legal frameworks should be updated for an “overshoot” world where countries would need to pursue “net-negative” strategies to bring temperatures down to 1.5C.

There were also discussions around governance of geoengineering technologies and the fairness and justice considerations that arise from the real-world impacts of breached targets.

The conference was being held just months after the ICJ’s advisory decision that limiting temperature increase to 1.5C should be considered countries’ “primary temperature goal”.

IIASA’s Shleussner told Carbon Brief that the decision provided “clarity” that countries had a “clear obligation to bring warming back to 1.5C”. He added:

“We may fail to pursue it from below, but it doesn’t relieve us from the obligation to then pursue it from above.”

Prof Lavanya Rajamani, professor of international environmental law at the University of Oxford, insisted that “1.5C was very much alive and well in the legal world”, but noted there were “very significant limits” to what could be achieved through the UN Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC) – the global treaty for coordinating the response to climate change – both today and in the future.

Summarising discussions around how countries can be pushed to deliver the “highest possible ambition” in future climate plans submitted to the UN, Rajamani urged delegates to be “tempered in [its] expectations of what we’re going to get from the international regime”. She added:

“Changing the narratives and practices at the national level are far more likely to filter up to the international level than trying to do it from a top-down perspective.”

In a parallel session, Prof Christina Voigt, a professor of international law at the University of Oslo, pointed out that overshoot would require countries to aspire beyond “net-zero emissions” as “the end climate goal” in national plans.

Stabilising emissions at “net-zero” by mid-century would result in warming above 1.5C, she explained, whereas “net-negative” emissions are required to deliver overshoot pathways that return temperatures to below the Paris Agreement’s aspirational limit. She continued:

“We will need frontrunners. Leaders, states, regions would need to start considering negative-emission benchmarks in their climate policies and laws from around mid-century. There will be an expectation that developed country parties take the lead and explore this ‘negativity territory’.”

Voigt added that it was “critical” that nations at the UNFCCC create a “shared understanding” that 1.5C remains the “core target” for nations to aim for, even after it has been exceeded. One possible place for such discussions could be at the 2028 global stocktake, she noted.

She said there would need to be more regulation to scale up CDR in a way that addresses “environmental and social challenges” and an effort to “recalibrate policies and measures” – including around carbon markets – to deliver net-negative outcomes.

In a presentation exploring governance of solar radiation management (SRM), Ewan White, a DPhil student in environmental law at the University of Oxford, said the ICJ’s recent advisory opinion could be interpreted to be “both for and against” solar geoengineering.

Countries tasked with drawing up global rules around SRM in an overshoot world would need to take a “holistic approach to environmental law”, White said. In his view, this should take into account international legal obligations beyond the Paris Agreement and consider issues of intergenerational equity, biodiversity protection and nations’ duty to cooperate.

Dr Shonali Pachauri, research group leader at IIASA, provided an overview of the equity and justice implications that might arise in an overshoot world.

First, she said that delays to emissions reductions today are “shifting the burden” to future generations and “others within this generation” – increasing the need for “corrective justice” and potential loss-and-damage payments.

Second, she said that adaptation efforts would need to increase – which, in turn, would “threaten mitigation ambition” given “constrained decision-making”.

Finally, she pointed to resource consumption issues that might arise in a world of overshoot:

“The different technologies that one might use for CDR often depend on the use of land, water, other materials – and this, of course, then means competing with many other uses [of resources].”

A separate stream focused on loss and damage. Session chair Dr Sindra Sharma, international policy lead at the Pacific Islands Climate Action Network, noted that the concept of loss and damage was “fundamentally transformed” by overshoot – adding there were “deep issues of justice and equity”.

However, Sharma said that the literature on loss and damage “has not yet deeply engaged with the specific concept of overshoot” despite it being “an important, interconnected issue”.

Sessions on loss and damage explored the existence of “hard social limits” under future overshoot scenarios, insurance and the need to bring more factors into assessments of habitability, including biophysical and social-economic constraints.

Communication challenges and next steps

At the conference, scientists and legal experts collaborated on a series of statements that summarised discussions at the conference – one for each research theme and an overarching umbrella statement.

IIASA’s Schleussner told Carbon Brief that the statements represented a “key outcome of the conference” that could provide a “framework” to guide future research.

Nevertheless, he noted that statements are a “work in progress” and set to be “further refined” following feedback from experts not able to attend the conference.

At the time of going to press, the overarching conference statement read as follows:

“Global warming above 1.5C will increase irreversible and unacceptable losses and damages to people, societies and the environment.

“It is imperative to minimise both the maximum warming and duration of overshoot above 1.5C to reduce additional risks of human rights violations and causing irreversible social, ecological and Earth system changes including transgressing tipping points.

“This is required by international law and possible by removing CO2 from the atmosphere and further reducing remaining greenhouse emissions.”

Conference organisers also pointed delegates to an open call for research on “pathways and consequences of overshoot” in the journal Environmental Research Letters. The special issue will be guest edited by a number of scientists who played a key role in the conference.

Meanwhile, communications experts at the conference discussed the challenges inherent in conveying overshoot science to non-experts, noting potential confusion around the word “overshoot” and the difficulties in explaining that the 1.5C limit, while breached, was still a goal.

Holly Simpkin, communications manager at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, urged caution when communicating overshoot science to the general public:

“I don’t know whether ‘overshoot’ is an effective communication framing. It is an important scientific question, but when it comes to near-term action and the requirements that an ambitious overshoot pathway would ask of us, emissions are what are in our control.

“We could spend 10 more years defining this and, actually, it’s quite complex…I think it’s better to be honest about that and to try to be more simple in that frame of communication, knowing that this community is doing a wealth of work that provides a technical basis for those discussions.”

The post Overshoot: Exploring the implications of meeting 1.5C climate goal ‘from above’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Overshoot: Exploring the implications of meeting 1.5C climate goal ‘from above’

Climate Change

China Briefing 19 February 2026: CO2 emissions ‘flat or falling’ | First tariff lifted | Ma Jun on carbon data

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s China Briefing.

China Briefing handpicks and explains the most important climate and energy stories from China over the past fortnight. Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Carbon emissions on the decline

‘FLAT OR FALLING’: China’s carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions have been either “flat or falling” for almost two years, reported Agence France-Presse in coverage of new analysis for Carbon Brief by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA). This marks the “first time” annual emissions may have fallen at a “time when energy demand was rising”, it added. Emissions fell 0.3% during the year, driven by a fall in emissions “across nearly all major sectors”, said Bloomberg – including the power sector. It said the chemicals sector was an exception, where emissions saw a “large jump from a surge of new plants using coal and oil” as feedstocks. The analysis has been covered around the world by outlets ranging from the New York Times, Bloomberg and BBC News through to Der Spiegel, CGTN and the Guardian.

TOP TASKS: President Xi Jinping listed “persisting in following the ‘dual-carbon’ goals” as one of eight “key” elements of economic work in 2026, according to a December speech just published in Qiushi, the Chinese Communist party’s leading journal for political theory. This included “deeply advancing” carbon reduction in key industries and “steadily promoting a peak in consumption of coal and oil”, according to the transcript. The National Energy Administration (NEA) also outlined a number of priority tasks for the department, including resolving “grid integration challenges” to encourage greater use of renewable energy and “boosting investment” in energy resources, said energy news outlet International Energy Net.

ETS EXPANSION: Meanwhile, the government has asked “heavy polluters” in several sectors not yet covered in China’s emissions trading scheme (ETS) to report their emissions for 2025, reported Bloomberg, in a “key step” for the further expansion of the carbon market. The affected industries are the “petrochemical, chemical, building materials (flat glass), nonferrous metals (copper smelting), paper and civil aviation industries”, according to the original notice posted by the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE), as well as steel and cement companies not yet covered by the ETS.

State Council issued ‘unified’ power market guidance

POWER TRADE: China will aim for “market-based transactions” to account for 70% of total electricity consumption by 2030, according to new policy guidance released by China’s State Council and published by International Energy Net. The policy also called for greater “integration” of cross-regional trading and “fundamentally sound” market-based pricing mechanisms. On renewable power, the guidance urged officials to “expand the scale of green power consumption” and establish a “green certificate consumption system that combines mandatory and voluntary consumption”, as well as encourage “implementation of inter-provincial renewable energy priority dispatch plans”. It also calls for “roll[ing] out spot trade nationwide by 2027, up from just 4% of the total transactions today”, reported Bloomberg.

CLEAN-POWER PUSH: An official at China’s National Development and Reform Commission said in a Q&A published by BJX News that establishing a “unified” national power market is “crucial for constructing a new power system”. A separate analysis by Beijing-based power services firm Lambda reposted on BJX News argues that China’s unified power-market reforms – which have been “more than two decades” in the making – will allow for “widespread integration” of renewable energy, resolving the challenge of wind and solar “generating but being unable to transmit and integrate”. Business news outlet Jiemian quoted Xiamen University professor Lin Boqiang saying that, while power-market reform may present clean-energy companies with “growing pains” in the short term, it will “force the industry to develop healthily” in the long term.

EU tariffs lifted on first firm’s China-built EV imports

‘SOFTENED’ STANCE: The Chinese government has “softened its stance” on electric vehicle (EV) manufacturers who seek to independently negotiate with the EU on prices for their exports to the bloc, said Reuters, after it previously “urged the bloc not to engage in separate talks with Chinese manufacturers”. The move came as Volkswagen received an exemption from tariffs for one of its EVs that is made in China and imported to the EU, which it committed to sell above a specific price threshold, reported Bloomberg. It added that the company also pledged to follow an import quota and “invest in significant battery EV-related projects” in the EU.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “China Briefing” email newsletter. All you need to know about the latest developments relating to China and climate change. Sent to your inbox every Thursday.

‘MADE IN EU’ MELTDOWN: Meanwhile, EU policymakers attempted to agree legislation that may force EV manufacturers to ensure “70% of the components in their cars are made in the EU” if they wish to receive subsidies, reported the Financial Times. A draft of the plan was ultimately rejected by nine European Commission leaders and commission president Ursula von der Leyen, Borderlex managing editor Rob Francis wrote on Bluesky.

BRAZIL BACKTRACKS: Brazil has “scrapped” a tariff exemption for Chinese EV manufacturers that allowed cars assembled in Brazil with parts imported from China to be sold at much lower prices than similar vehicles made from parts imported from other countries, reported the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post. Separately, Bloomberg reported on the surge of tariff-free Chinese EVs that has enabled Ethiopia to ban the import of combustion-engine cars.

PRICE-WAR BAN: The Chinese government has “banned carmakers from pricing vehicles below cost”, reported Bloomberg, in an effort to clamp down on a “persistent price war” affecting the industry. China’s car industry, “particularly in the EV segment”, has seen “aggressive discounting, subsidies and bundled promotions” pushing down profitability for companies across the supply chain, said the state-run newspaper China Daily.

More China news

- POWERFUL WIND: China has connected a 20-megawatt offshore wind turbine – the “world’s most powerful” and “equivalent to a 58-story building” – to the grid, reported state news agency Xinhua.

- PROVINCIAL MOVES: Anhui has become the first Chinese province to release data on how much carbon different forms of power in the province emits per kilowatt-hour of power, according to power news outlet BJX News.

- RARE-EARTH RUNES: China may hold a “policy briefing” on export restrictions for rare earths and other critical minerals in March, according to Reuters.

- NO CHINA CREDITS: The US confirmed that clean-energy tax credits will not be available for companies that are “overly reliant on Chinese-made equipment”, said Reuters.

Spotlight

Ma Jun: ‘No business interest’ in Chinese coal power due to cheaper renewables

Carbon Brief spoke with Ma Jun, one of China’s most well-known environmentalists, about how open data can keep pressure on industry to decarbonise and boost interest in climate change.

Ma is director of the Beijing-based Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE), an organisation most well known for developing the Blue Map, China’s first public database for environment data.

Speaking to Carbon Brief during the first week of COP30 in Brazil last November, the discussion covered the importance of open data, key challenges for decarbonising industry, China’s climate commitments for 2035, cooperation with the EU and more.

Below are highlights from the conversation. The full interview can be found on the Carbon Brief website.

Open data is helping strengthen climate policy

- On how data transparency prevents environmental pollution in China: “From that moment [when the general public began flagging environmental violations on social media in 2014], it was no longer easy for mayors or [party] secretaries to try to interfere with the enforcement, because it’s being made so transparent, so public.”

- On encouraging the Chinese government to publish data: “The ministry felt that they had the backing from the people, basically, which helped them to gain confidence that data can be helpful and can be used in a responsible way.”

- On China’s new corporate disclosure rules: “We’re talking about what’s probably the largest scale of corporate measuring and disclosure now happening [anywhere in the world].”

- On the need for better emissions data: “It will be impossible to get started without proper, more comprehensive measuring and disclosure, and without having more credible data available.”

‘Green premium’ still challenging despite falling prices

- On the economics of coal: “There’s no business interest for the coal sector to carry on, because increasingly the market will trend towards using renewables, because it’s getting cheaper and cheaper”.

- On paying for low-carbon products: “When we engage with them and ask why they didn’t expand production, they say that producing these items will have a ‘green premium’, but no one wants to pay for that. Their users only want to buy tiny volumes for their sustainability reports.”

- On public perceptions in China of climate change: “It’s more abstract – [we’re talking about] the end of the century or the polar bears. People don’t feel that it’s linked with their own individual behaviour or consumption choices.”

Climate cooperation in a new era

- On criticism of China’s climate pledge: “In the west, the cultural tendency is that if you want to show that you’re serious, you need to set an ambitious target. Even if, at the end of the day, you fail, it doesn’t mean that you’re bad…But in China, the culture is that it is embarrassing if you set a target and you fail to fully honour that commitment.”

- On global climate cooperation: “The starting point could be transparency – that could be one of the ways to help bridge the gap.”

The role of civil society in China’s climate efforts

- On working in China as a climate NGO: “What we’re doing is based on these principles of transparency, the right to know. It’s based on the participation of the public. It’s based on the rule of law. We cherish that and we still have the space to work [on these issues].”

- On the climate consensus in China: “The environment – including climate – is the area with the biggest consensus view in [China]. It could be a test run for having more multi-stakeholder governance in our country.”

This interview was conducted by Anika Patel at COP30 in Belém on 13 November 2025.

Watch, read, listen

GREEN ALUMINIUM: Lantau Group principal David Fishman wrote on LinkedIn about why China’s aluminium smelters are seeking greater access to low-carbon power, following heated debate over a Financial Times article.

STRONGER THAN EVER: Isabel Hilton, chair of the Great Britain-China Centre, spoke on the Living on Earth podcast about China’s renewables push and exports of clean-energy technologies.

CUTTING CORNERS?: Business news outlet Caixin examined how a surge in turbine defects at one wind farm could be due to “aggressive cost-cutting and rapid installation waves”.

POLES APART: BBC News’ Global News Podcast examined the drivers behind China’s flatlining emissions, as revealed by Carbon Brief.

600

In gigawatts, China’s total capacity of coal plants that are “flexible” and – in theory – better able to balance the variability of renewables, according to a new report by the thinktank Ember.

New science

- China will see a 41% decline in in coal-mining jobs over the next decade under current climate policies | Environmental Research Letters

- During 2000-20, China’s per-person emissions of CO2 increased from 106kg to 539kg in urban households and from 35kg to 202kg in rural households, indicating that the inequality between urban and rural households is shrinking | Scientific Reports

Recently published on WeChat

China Briefing is written by Anika Patel and edited by Simon Evans. Please send tips and feedback to china@carbonbrief.org

The post China Briefing 19 February 2026: CO2 emissions ‘flat or falling’ | First tariff lifted | Ma Jun on carbon data appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Ma Jun: ‘No business interest’ in Chinese coal power due to cheaper renewables

Open and transparent data can accelerate the decarbonisation of China’s industries and boost public interest in climate change, says Ma Jun.

Ma – one of China’s most recognisable environmental activists – says that early experiments with publishing real-time air quality data have paved the way for greater openness from the Chinese government towards publishing greenhouse gas emissions data.

However, he tells Carbon Brief in a wide-ranging interview, more needs to be done to encourage “multi-stakeholder” participation in climate efforts and to improve corporate emissions disclosure.

He also notes that China faces significant “challenges” in reducing emissions from “hard-to-abate” sectors, where companies struggle to find consumers willing to pay a “green premium” for low-carbon versions of their products.

Ma is the founder and director of the Institute of Public and Environmental Affairs (IPE), a Beijing-based NGO focused on environmental information disclosure and public participation.

The IPE is most well-known for developing the Blue Map, China’s first public database for environment data.

Ma has been a long-term advocate for environmental protection in China.

Prior to founding the IPE, he covered environmental pollution as an investigative reporter at the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post.

He also authored China’s first book on the serious water pollution challenges facing the country.

Speaking to Carbon Brief during the first week of COP30 in Brazil last November, the discussion covered the importance of open data, key challenges for decarbonising industry, China’s climate commitments for 2035, cooperation with the EU and more.

- On how data transparency prevents environmental pollution in China: “From that moment [that the general public began flagging environmental violations on social media], it was no longer easy for mayors or [party] secretaries to try to interfere with the enforcement, because it’s being made so transparent, so public.”

- On encouraging the Chinese government to publish data: “The ministry felt that they had the backing from the people, basically, which helped them to gain confidence that data can be helpful and can be used in a responsible way.”

- On China’s new corporate disclosure rules: “We’re talking about what’s probably the largest scale of corporate measuring and disclosure now happening [anywhere in the world].”

- On air-pollution policies creating a template for climate action: “It started from the pollution control side and now we want to see that happen on the climate side.”

- On paying for low-carbon products: “When we engage with them and ask why they didn’t expand production, they say that producing these items will have a ‘green premium’, but no one wants to pay for that. Their users only want to buy tiny volumes for their sustainability reports.”

- On public perceptions of climate change: “It’s more abstract – [we’re talking about] the end of the century or the polar bears. People don’t feel that it’s linked with their own individual behaviour or consumption choices.”

- On the need for better emissions data: “It will be impossible to get started without proper, more comprehensive measuring and disclosure, and without having more credible data available.”

- On criticism of China’s climate pledge: “In the west, the cultural tendency is that if you want to show that you’re serious, you need to set an ambitious target. Even if, at the end of the day, you fail, it doesn’t mean that you’re bad…But in China, the culture is that it is embarrassing if you set a target and you fail to fully honour that commitment.”

- On global climate cooperation: “The starting point could be transparency – that could be one of the ways to help bridge the gap.”

- On the economics of coal: “There’s no business interest for the coal sector to carry on, because increasingly the market will trend towards using renewables, because it’s getting cheaper and cheaper”.

- On working in China as a climate NGO: “What we’re doing is based on these principles of transparency, the right to know. It’s based on the participation of the public. It’s based on the rule of law. We cherish that and we still have the space to work [on these issues].”

- On the climate consensus in China: “The environment – including climate – is the area with the biggest consensus view in [China]. It could be a test run for having more multi-stakeholder governance in our country.”

The transcript below has been edited for length and clarity.

Carbon Brief: You have been at the forefront of environmental issues in China for decades. How would you describe the changes in China’s approach to climate and environment issues over the time you’ve been observing them?

Ma Jun: I started paying attention to the issues when I got the chance to travel in different parts of China. I was struck by the environmental damage, particularly on the waterways, the rivers and lakes, which do not just have all these eco-impacts, but also expose hundreds of millions to health hazards.

That got me to start paying attention. So I authored a book called China’s Water Crisis and readers kept coming back to me to push for solutions. I delved deeper into the research and I realised that it’s quite complicated – not just that the magnitude [of the problem] is so big, but that the whole issue is quite complicated, because we copied rules, laws and regulations from the west but enforcement remained weak.

There are huge externalities, but companies would rather just cut corners to be more competitive, put simply. Behind that, there was a doctrine before of development at whatever cost. That was the starting point in China – not just for policymakers, even people in the street, if you asked them at that time, most likely [they] would say: “China’s still poor. Let’s develop before we even think about the environment.”

But that started changing, gradually. Unfortunately, it needed the “airpocalypse” in Beijing and the big surrounding regions to really motivate that change.

In 2011, Beijing suffered from very bad smog and millions upon millions of people made their voices heard – that they want clean air.

The government lent an ear to them and decided to start from transparency, monitoring and disclosing data to the public. So two years after it started and people were being given hourly air quality data [in 2011] – you realised how bad it was. In the first month [of 2013], the monthly average was over 150 micrograms. The WHO standard was 10 at the time – now it’s dropped to five. [Some news reports and studies, based on readings published at the time by the US embassy in Beijing, note significantly higher figures.]

We believe that it’s good to have that data – of course, it’s very helpful – but it’s not enough. Keeping children indoors or putting on face masks are not real solutions, we need to address the sources. So we launched a total transparency initiative with 24 other NGOs calling for real-time disclosure of corporate monitoring data.

To our surprise, the ministry made it happen. From 2014, tens of thousands of the largest emitters, every hour, needed to give people air [quality] data, and every two hours for water [quality].

We then launched an app to help visualise that for neighbourhoods. For the first time, people could realise which [companies] are not in compliance. Even super-large factories – every hour, if they were not in compliance, then they would turn from blue to red [in the app].

And so many people made complaints and petitioned openly – sharing that on social media, tagging the official [company] account. That triggered a chain reaction and changed that dynamic that I described.

From that moment, it was no longer easy for mayors or [party] secretaries to try to interfere with the enforcement, because it’s being made so transparent, so public. The [environmental protection] agencies got the backing from the people and knocked the door open – and pushed the companies to respond to the people.

Then, the data is also used to enable market-based solutions, such as green supply chains and green finance.

Starting first with major multinationals and then extending to local companies, companies compared their lists with our lists before they signed contracts. If any of their [supplier] companies were having problems, they could get a push notification to their inbox or cell [mobile] phone.

That motivates 36,000 [companies] to come to an NGO like us – to our platform – to make that disclosure about what went wrong and how we try to fix the problem, and after that measure and disclose more kinds of data, starting with local emission data and now extending to carbon data.

And for banking and green finance, an NGO like us now helps banks track the performance of three million corporations who want to borrow money from them, as part of the due diligence process. These are just tiny examples to try to demonstrate that there’s a real change.

Before, when I got started, the level of transparency was so limited. When we first looked at government data, at the beginning, there were only 2,000 records of enforcement. So we launched an index, assessed performance for 10 years across 120 cities.

During this process, [we also saw] consensus being made. In 2015, China’s amended Environmental Protection Law [came into effect] and created a special chapter – chapter five – titled [information] transparency and public participation. That was the first ever piece of legislation in China to have such a chapter on transparency.

CB: What motivated that? Was it because they’d already seen this big public backlash?

MJ: They started listening to people and the demand for change, for clean air. And then they started seeing how the data can be used – not to disrupt the society, but to help to mobilise people.

The ministry felt that they had the backing from the people, basically, which helped them to gain confidence that data can be helpful and can be used in a responsible way. Before, they were always concerned about the data, particularly on disruption of social stability, because our data is not that beautiful at the beginning, due to the very serious pollution problem.

When our organisation got started, nearly 20 years ago, 28% of the monitored waterways – nationally-monitored rivers – reported water that was good for no use. Basically, it is so polluted that it’s not good for any use. [Some] 300 million [people] were exposed to that in the countryside, it was very serious.

We’re talking about the government changing its mindset. Of course, the reality is that they found [the data] can be used the responsible way and can be helpful, so they decided to embrace that and to tolerate that, to gradually expand transparency.

Now, China is aligning its system with the International Sustainability Standards Board (ISSB). The environment ministry also created a disclosure scheme, with 90,000 of China’s largest [greenhouse gas] emitters on the list. We and our NGO partners tried to help implement that. We’re talking about billions of tonnes of carbon emissions.

It would have been hard to imagine before, but we’re talking about what’s probably the largest scale of corporate measuring and disclosure now happening [anywhere in the world].

Of course, it’s still not enough. Last year, we also helped the agency affiliated with the ministry to develop a guideline on voluntary carbon disclosure, targeting small and medium sized companies. We now have a new template on our platform – powered by AI – and a digital accounting tool that helps our users measure and disclose nearly 70m tonnes [of carbon dioxide equivalent] last year.

CB: Is there appetite on the industrial side to proactively get involved? Or is local regulation needed that mandates involvement?

MJ: At the beginning, no. If we have the dynamic that I described – at the beginning, whoever cut corners became more competitive. This caused a “race to the bottom” situation and even good companies find it quite difficult to stick to the rules.

But then the dynamic changed. Whoever’s not in compliance with the law will be kicked out of the game. Not only would they receive increasingly hefty penalties or fines, but the data will be put into use in supply chains. Many of our users – the brands – integrate that data into their sourcing, meaning that if [suppliers] don’t solve the problem they will lose contracts. And also banks could give them an unfavourable rating.

All this joint effort could create some sort of – of course, it’s [only a] chance – but some kind of a stick. But it’s also a kind of carrot, because those who decided to do better now benefit. If someone loses business [because they cannot help their consumer with compliance], then that business will [instead] go to those who want to go green.

This change in dynamic is very helpful. It started from the pollution control side and now we want to see that happen on the climate side. That’s why we decided to develop the blue map for zero carbon, to try to map out and further motivate the decarbonisation process – region by region, sector by sector.

You asked about corporations – this is extremely important. China is the factory of the world and 68% of carbon emissions still relate either to the direct manufacturing process or to energy consumption to power the industrial production. So it is very important to motivate them, to create both rules and stimulus – both stick and carrot.

But if you don’t have a stick, you can never make the carrot big enough. That is an externality problem, you never really solve that. We’ve now managed to solve the basic problem – non-compliance and outrageous violations. But that’s the first step. Deep decarbonisation – not just scope one and two, but extending further upstream to reach heavy industry, the hard-to-abate industries – now this is the challenge.

CB: What are your expectations for industrial decarbonisation more broadly, especially given the technology bottlenecks?

MJ: There are still bottlenecks, but we see, actually, some progress is being made. Now corporations in China understand that they need to go in [a low-carbon] direction and some of them are actually motivated to develop innovative solutions.

For example, several major steel manufacturers managed to be able to find ways to produce much lower-carbon steel products. In the aluminium [sector] they also tried and also batteries. Unfortunately, these remain as only pilot projects.

When we engage with them and ask why they didn’t expand production, they say that producing these items will have a “green premium”, but no one wants to pay for that. Their users only want to buy tiny volumes for their sustainability reports – for the rest, they just want the low-cost ones.

They said, the more we produce the green products, the bigger our losses. So we decided to leave these products in our warehouse.

Then we engaged with the brands – the real estate industry, the largest user of iron and steel – and the automobile industry, the second largest. They claimed that if they [purchase greener materials], they would pay a green premium, but their users and consumers have no idea about [green consumption]. They only want to buy the cheapest products – and the more [these manufacturers] produce, the more they suffer losses.

So this means we need a mechanism, with multi-stakeholder participation, to share the burden of that transition – to share that cost of the green transition.

That green premium can only be shared, not one single stakeholder can easily absorb all of this given all the breakneck competition in China – involution – it’s very, very serious and so companies are all stuck there.

What we’re trying to do is to help change that. We assessed the performance of 51 auto brands and tried to help all the stakeholders understand which ones could go low-carbon.

But it’s not enough just to score and rank them. We also need to engage with the public, to have them start gaining an understanding that their choice matters. So how – it’s more difficult, you know? Pollution is much easier. We told them: “Look, people are dumping all this waste.”

CB: It’s all visible.

MJ: Yeah, when people suffer so seriously from pollution – air, water and soil pollution – they feel strongly. They wrote letters to the brands, telling them that they like their products but they cannot accept this.

But on climate, it’s more abstract – [we’re talking about] the end of the century or the polar bears. People don’t feel that it’s linked with their own individual behaviour or consumption choices.

We decided to upgrade our green choice initiative to the 2.0 level. This new solution we developed is called product carbon scan. Basically, you take a picture of any product and services products and an AI [programme] will figure out what product that is and tell you the embodied carbon of that product.

Now, it’s getting particularly sophisticated with automobiles. The AI now – from this year – for most of the vehicles on the streets of China, can figure out not just which brand it is, but which model. We have all these models in our database – 700-800 models and 7,000-8,000 varieties of cars, all of which have specific carbon footprints.

CB: How do you account for all of the different variables? If something changes upstream, if a supplier changes – how do you account for that?

MJ: The idea is like this – now, this is mostly measured by third parties, our partners. We also have our emission factors database that we developed. So we know that, as you said, there are all these variables. For the past six months, we got our users to take pictures of 100,000 cars. We distributed them to 50 brands and [calculated] that the total carbon footprint was 4.2m tonnes, for the lifecycle of these 100,000 cars. Each brand got their own share of this.

So we wrote letters – and we’re still writing letters now, 10 NGOs in China, we’re writing letters now to the CEOs of these 50 brands – to tell them that this is happening. Our users, consumers of their products, are paying attention to this and are raising questions. We have two demands.

First, have you done your own measuring for the product you sell in China? Do you have plans to measure and disclose those specific details? Because if third parties can do it, so can they. It’s not space technology, they can do it and obviously they own all this data. They understand much better about the entire value chain and it’s much easier for them to get more accurate figures. With the “internet of things” and new technologies, for some products, they can get those details already, so the auto industry should be getting close to [achieving] that.

The second question is, you all have set targets for carbon reduction and carbon neutrality. We know that most of you are not on track. Even the best ones – Mercedes-Benz is at the top of our rankings – are seeing their carbon intensity going up. Not just the total volume [of emissions], but products’ carbon intensity is going up instead of going down. So, obviously, they haven’t really decarbonised their upstream – steel and aluminium. So [we ask them]: “What’s your plan? Can you give me an actionable, short- or mid-term plan on the decarbonisation of these upstream, hard-to-abate sectors?”

I think this is the way to try to tap into the success of pollution control and now extend that to cover carbon.

CB: It seems a challenge facing China’s climate action that policymakers often flag is MRV [monitoring, reporting and verification] and data in general. You’re the expert on this. Would you agree? Are there big challenges around MRV that China needs to address before it can progress further?

MJ: This is a prerequisite, in my view. To have [to] measure, disclose and allow access to data is a prerequisite for any meaningful multi-stakeholder effort. I wouldn’t underestimate the challenge in the follow-up process – the solutions, the innovations, the new technologies that need to be developed to decarbonise – but it will be impossible to get started without proper, more comprehensive measuring and disclosure, and without having more credible data available.

I take this as a starting point – a most important starting point. I’m so happy to see that there’s a growing consensus on that. In China, the government decided to embrace the concept of the ISSB, embrace the concept of ESG reporting, and to allow an NGO like us to try to help with the disclosure mechanism.

This is very powerful and very productive, and the reason that we could create that solution is because China pays so much attention to product carbon footprints, of course, motivated by the EU legislations, like the carbon border adjustment mechanism (CBAM) and others. In some ways, it’s quite interesting to see the EU set these very progressive rules, but then China responds and decides to create solutions and scale them up.

On the product carbon footprint alone, the Ministry of Ecology and Environment (MEE) coordinated 15 different ministries to work on it, with a very tight schedule – targets set for 2027 and then 2030 – [implying] very fast progress. We work together with our partners on a new book telling businesses – based on emission factors – how to handle it and how to proceed, in terms of practical solutions.

All this is just to say that, on the data and MRV side, China has already overcome its initial reluctance, or even resistance. Now [it] is in the process of not just making progress and expanding data transparency, but also trying to align that with international practice.

And at COP30, I actually launched a new report [titled the Global City Green and Low-Carbon Transparency Index]…The transparency index actually highlighted that, of course, developed cities are still doing better, but a whole group of Chinese cities are quickly catching up. Trailing behind are other global south cities.

When China decides to do something, it isn’t just individual businesses or even individual cities [that see action taken]. There will be more of a platform-based system – meaning there is an [underlying] national requirement, which can help to level the playing field, with regions or sectors possibly taking up stricter requirements, but not being able to compromise the national ones [by setting lower targets].

So, with MRV, I have some confidence. That doesn’t mean it’s easy. Particularly on the product carbon footprint, there are so many challenges. Trying to make emission factors more accurate is quite difficult, because products have so many components and the whole value chain can be very long and complicated. But with determination, with consensus, I’m still confident that China can deliver.

And in the meantime, what is now going on in China, increasingly, could become a contribution to global MRV practice.

CB: It’s interesting that you mentioned that. Talking to people at the COP30 China pavilion, people from global south countries see China as a climate leader and want to learn about what’s going on in China. By contrast, developed countries seem more focused on the level of ambition in China’s NDC [its climate pledge, known as a nationally determined contribution]. How would you view China’s role in climate action in the next five years?

MJ: On the NDC, my personal observation – I come from an NGO, so I don’t represent the government’s decision here – is that culturally, there’s some sort of differences, nuanced differences – or very obvious differences – here.

In the west, the cultural tendency is that if you want to show that you’re serious, you need to set an ambitious target. Even if, at the end of the day, you fail, it doesn’t mean that you’re bad, you still achieve more than if you’d set a lower target. That’s the mentality.

But in China, the culture is that it is embarrassing if you set a target and you fail to fully honour that commitment. So they tend to set targets in a slightly more conservative way.

I’m glad to see that [China’s] NDC is leaving space for flexibility – it said that China will try to achieve a higher target. This is the tone, and in my view it gives us the space and the legitimacy to try to motivate change and develop solutions to bend the curve faster. Even if the target is not that high, we know that we will try to beat that.

And then, there’s the renewables target for 1,200 gigawatts (GW) by 2030, a target that was achieved last year – six years early. Now we’ve set a target of 3,600GW – that means adding 180GW every year. But, as you know, over the past several years [China’s renewable additions] have been above 200GW.

So you can see that there’s a real opportunity there and we know that China will try to overdeliver. There’s no kind of a good or bad, or right or wrong, with these two different cultural [approaches].

But one thing I hope that we all focus more on is implementation – on action. Because we do see that, for some of the global targets that have already been set, no-one seems to be paying any real attention to them – such as the tripling of [global] renewable capacity.

We all witnessed that, in Dubai at COP28, a target was agreed and accepted by the international community. China’s on track, but what about the others? Most countries are not on track.

The global south, it’s not only for their climate targets – the [energy] transition is essential for their SDG [sustainable development goal] targets. But now they lag so far behind. That’s a pity, because now there’s enough capacity – and even bigger potential – to help them access all this much faster.

But geopolitical divides, resource competition, nationalism, protectionism – all of this is dividing us. It’s making global climate governance a lot more difficult and delaying the process to help [others in the] global transition. It’s very difficult to overcome these problems – probably it will get worse before it gets better.

But if we truly believe that climate change is an existential threat to our home planet, then we should try to find a way to collaborate a bit more. The starting point could be transparency – that could be one of the ways to help bridge the gap.

In China, we used to have a massive gap of distrust between different stakeholders. People hated polluting factories, but they also had suspicions around government agencies giving protection to those factories. So there’s all this distrust.

With transparency, it’s easier for trust to be built, gradually, and the government started gaining confidence [in sharing data] because they saw with their own eyes that people came together behind them. Before, [people] always suspected that [the government] were sheltering the polluters. But from that moment, they realised that the government was serious and so gave them a lot of support.

Globally – maybe I’m too negative – I do think that it would [improve the chances for us all to collaborate] if we had a global data infrastructure and a global data platform, that doesn’t just give [each country’s] national data but drills down – province by province, city by city, sector by sector and, eventually, to individual factories, facilities and mines. For each one of these, there would be a standardised reporting system, giving people the right to know. I think through this we could build trust and use it as a starting point for collaboration.

I sit on several international committees – on air, water, the Taskforce on Nature-related Financial Disclosures (TFND), transition minerals, and so on. In each of these, I often make suggestions on building global data infrastructure. Increasingly, I see more nodding heads, and some have started to make serious efforts. TNFD is one example. They already have a proposal to develop a global data facility on data. The International Chamber of Commerce also put forward a proposal on the global data infrastructure on minerals and other commodities.

Of course, in reality, there will be many difficulties – data security, for example. So maybe it cannot be totally centralised, we need to allow for decentralised regional systems, but you could also create catalogues to allow the users to [dig into] all this data.

CB: And that then inspires people to look into issues they care about?

MJ: Yes and through that process, we will create more consensus, create more trust and gradually formulate unified rules and standards.

And we need innovative solutions. In today’s world, security is something that’s not just paid attention to by China, in the west it’s a similar [story]. There are a lot of concerns about data security – growing concerns – so I think eventually there will be innovation to solve them. I’m still hopeful!

CB: Speaking of international cooperation, how has the withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement affected prospects for China-EU cooperation?

MJ: It will have a mixed impact, of course. Having the largest economy and second-largest emitter withdraw will have a big impact on global climate governance, and will in some way create negative pressure on other regions, because we’re all facing the question of: “If they don’t do it, why should we?” We also have those questions back home. I’m sure the EU is also facing this question.

But in the meantime, I hope that China and the EU realise that they have no choice but to work together – if they still, as they claim, truly believe in [the importance of] recognising the existential threat posed by climate change, then what choice do they have but to work together?

Fundamentally, we need a multilateral process to deal with this global challenge. The Paris Agreement, with all its challenges, still managed to help us avoid the worst of the worst. We still need this UNFCCC process and we need China and the EU to help maintain it.

At the last COP[29 in Azerbaijan], for the first time, it was not China and the US who saved the day. Before, it was always the US and China that made a deal and helped [shepherd] a global agreement. But last year, it was China and the EU that made the agreement and then helped to reach [a global deal] in Azerbaijan.

I do think that China and the EU have both the intention and the innovative capacity, as well as a very, very powerful business sector. I’m still hopeful that these two can come together at this COP [in Brazil].

CB: We’ve spoken a lot about heavy industry and industrial processes. Coal is a very big part of China’s emissions profile. In the short term, how do you see China’s coal use developing over the next five to 10 years?

This ties into that complicated issue of the geopolitical divide. The original plan was to use natural gas as the transition [fuel], which would make things much easier. But geopolitical tensions means gas is no longer considered safe and secure, because China has very little of this resource and has to depend on the other regions, including the US, for gas.

That, in some way, pushed towards authorising new coal power plants and, in some way, we are all suffering for that. In the west as well. We all have to create massive redundancies for so-called insecurity, we’re all bearing higher costs and we’re all facing the risk of stranded assets, because we have such a young coal-power fleet.

The only thing we can do is to try to make sure that these plants increasingly serve only as a backup and as a way to help absorb high penetration of renewables, because now this is a new challenge. Renewables have been expanding so fast that it’s very difficult – because of its intermittent nature – to integrate it into the power grid. New coal power can help absorb, but only if we can make [it] a backup and not use it unless there’s a need. Of course, that means we have to pay to cover the cost for those coal plants.

The funny thing is that there’s no business interest for the coal sector to carry on, because increasingly the market will trend towards using renewables, because it’s getting cheaper and cheaper. So the coal sector, for security and integration of renewables, will be kept. But it will play an increasingly smaller role. In the meantime, the coal sector can help balance the impact through making chemicals, rather than just energy.

In the meantime, [we need to] try to find ways to accelerate the whole energy transition and electrify our economy even faster. That’s a clear path towards both carbon peaking and carbon neutrality in China.

It’s already going on. Carbon Brief’s research already highlights some of the key issues, such as from March [2024] emissions are actually going down. That cannot happen without renewables, because our electricity demand is still going up significantly. In the meantime, the cost of electricity is declining.

This allows China to find its own logic to stick to the Paris Agreement, to stick to climate targets and even try to expand its climate action, because it can benefit the economy. It can benefit the people.

I think Europe probably could also learn from that, because Europe used to focus on climate for the climate’s sake. With [the Russia-Ukraine] war going on, that makes it even more difficult.

CB: You mean the green economy narrative?

MJ: Yes, the green economy narrative is not highlighted enough in Europe. Now, suddenly, it’s about affordability, it’s about competition, and suddenly they feel that they’re not in a very good position. But China actually focuses more on the green economy side. China and the EU could – hand-in-hand – try to pursue that.