At the final plenary meeting of the Dubai climate conference, COP28 president Dr Sultan Al Jaber declared that the package of key decisions taken in Dubai would be known as the “UAE consensus”.

This threw a spotlight on one of the quirks of the UN climate negotiations: that COP decisions are always adopted by consensus.

Unlike most other multilateral environmental conventions, there is no majority voting rule, not even a “last resort” one, that can be invoked if there is no consensus.

This is not due to an unusual choice by the climate regime’s architects, but rather to the failure of the countries involved to agree on how to take decisions, at the very start of the regime in the early 1990s – and ever since.

Consensus, thus, applies by default, rather than by design.

But there is more to this story: disagreement over decision-making rules has its origins not in disputes among lawyers, but rather in the deliberate strategy of obstructionist forces aiming to weaken the intergovernmental response to climate change.

How did this happen? And how has consensus decision-making played out over the decades?

Rules of procedure

The international climate regime was established under the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC, or “Convention”), signed at the Rio Earth Summit in 1992.

This entered into force in 1994 and – under Article 7.3 of the Convention – one of the tasks for the very first “Conference of the Parties” (COP1), held in Berlin in 1995, was to adopt a set of “rules of procedure” for itself.

Moreover, according to Article 7.2k of the Convention, these rules had to be adopted by consensus.

Defining “rules of procedure” is usually relatively straightforward for new regimes: the rules set out rather standard requirements for matters such as election of chairpersons, asking for the floor in a plenary meeting, circulation of written proposals, provision of interpretation into UN languages, raising points of order and so on.

In terms of decision-making, UN rules of procedure typically establish that decisions should be taken by consensus, while defining a “last resort” voting majority that can be invoked in cases where “all efforts have been exhausted and no consensus reached”.

The draft rules of procedure were prepared by the climate secretariat for governments to work on in preparation for COP1. They were modelled on those of the 1987 Basel Convention on transboundary hazardous waste (the most recent relevant treaty), and other precedents, such as the treaties on combating ozone depletion and the UN general assembly (UNGA).

Draft rule 42 included provision for a two-thirds “last resort” voting majority which, like the rest of the draft rules of procedure, was unremarkable in the UN context.

The same “last resort” voting majority was in place – but never used – during the negotiation of the Convention itself in 1991-1992, when negotiators had drawn on UNGA procedures to structure their work.

Some political wranglings over the finer points of the rules of procedure were to be expected. But what should have been a rather routine matter escalated into a major political storm in the run-up to COP1, when members of the oil producers’ cartel the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries (OPEC) – principally Saudi Arabia and Kuwait, also Nigeria, Iran and others – began to argue that there should be no “last resort” voting rule at all. Instead they argued that substantive decisions should be taken only by consensus.

In insisting on consensus as the basis for substantive decisions, these oil exporting countries were receiving advice from US-based lobbyists with links to fossil fuel interests, automobile companies and libertarian political forces, notably the now-disbanded Global Climate Coalition, along with the Climate Council and its top lawyer the late Don Pearlman.

These lobbyists would openly pass notes to the Saudi or Kuwaiti delegations during plenary meetings, or even whisper in their ears (this was before mobile phones), prompting these delegates to raise objection after objection.

The interference from lobbyists became so brazen, that the chair of the negotiations in the run-up to COP1 in Berlin – Argentinian diplomat Raul Estrada Oyuela – banned anyone without a government badge from the plenary room floor, as he explained to me later. This ruling remained in place until the advent of mobile phones rendered it irrelevant.

Holding up rule 42

The disagreement over how general decision-making should take place within the COP process was not the only hold-up to the last-resort voting rule (42). There were wider disputes over climate finance, with donor countries – especially the US and France – insisting financial decisions should be taken by consensus, and developing countries wanting these to go to a vote.

Muddying the waters further, in a late move at the final negotiating session before COP1, OPEC proposed that the rules of procedure enshrine a dedicated seat for fossil fuel dependent countries on the influential committee, the COP bureau. This would match the seat already granted to small island developing states on account of their vulnerability (rule 22).

(This issue was, in the end, resolved through an informal understanding that fossil fuel dependent countries would always have a seat on the bureau, but through one of their traditional regional groups (usually Asia), rather than dedicated representation.)

Recognising that the Convention by itself was too weak to solve climate change, negotiators included a clause in the treaty calling for a “review” of the “adequacy” of developed country commitments at COP 1 (Article 4.2(d)). As COP 1 opened, there was “general agreement” that those commitments were indeed “inadequate”, although no consensus over what should be done about it. But one of the main options on the table was to launch a new round of negotiations on a stronger treaty, most likely a protocol.

The Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) and Germany had in fact already tabled draft protocols, including legally binding emission targets for developed countries.

Faced with the prospect that a new round of negotiations might result in substantially stronger curbs on emissions, oil exporting countries and their backers were “determined” to shape decision-making rules at COP1, ensuring that any protocol could only be adopted by consensus. Writing at the time, lawyers Sebastian Oberthur and Hermann Ott explained that “by requiring a consensus for the adoption of protocols Saudi Arabia and Kuwait were determined to preserve their ability to block any strong international agreement”.

An impasse

Despite extensive diplomatic outreach in the run-up to Berlin, and the best efforts of COP president Angela Merkel, the standoff over the “last resort” voting rule (42) could not be resolved at COP1.

Emerging agreement that decisions on financial matters should be taken by a double majority of donor and recipient countries (a pragmatic solution applied in other intergovernmental forums) was blocked, because the US and some EU countries insisted on consensus for these issues.

In what has been described as a “tactical move”, given that it had zero chance of being accepted, OPEC countered that all decisions – including financial ones – should be taken by a three-fourths majority vote. This was popular with developing countries, but out of the question for donors, who would always be outvoted under such a rule. The result was an impasse.

Nearly 30 years on, the entire rules of procedure remain in draft form, although they are applied at each COP session, as if they were adopted.

The exception is draft rule 42, which is not applied. The two main bracketed options – which signify they have not been agreed by all parties – for rule 42 are decision-making by consensus or consensus with a two-thirds “last resort” voting majority.

These have been frozen in time for the past three decades, with alternatives also for financial matters. But because no “last resort” voting rule has been agreed, the default is that decisions are indeed taken by consensus.

Consensus caveats

There is a caveat to the consensus imperative. Some decisions can, in fact, be taken by a majority vote.

The Convention, Kyoto Protocol and the Paris Agreement can be amended with a three-quarters majority vote. This is because the Convention itself – articles 15 and 16 to be precise – rather than the unadopted rules of procedure, specifies this decision-making rule (and the other treaties apply the Convention’s rules).

Some matters set out in the rules of procedure can also be settled by voting, including challenges to a chair’s ruling on points of order that can be settled by a simple majority vote (rule 34) and the election of officers to the COP or equivalent bureau (rule 22).

Some chairs have occasionally threatened to take these procedural matters to the vote, but this has usually resulted in recalcitrant parties backing down.

A protracted dispute in May 2012 over who should chair the ad hoc group on the Durban Platform (ADP – the body that negotiated the Paris Agreement) for example, provoked South African ambassador Nozipho Joyce Mxakato-Diseko to threaten to call a vote. A solution was eventually found to appoint co-chairs, without a vote.

In a very small handful of cases, a procedural vote according to rule 34 has been called, in the form of a show of hands, but always in a subsidiary body or ad hoc group, and never in a COP.

The most high-profile case was in June 2013, during a lengthy debate over the SBI agenda. Faced with a point of order from the G77 and China, which called for substantive work to proceed, chair Tomasz Chruszczow (Poland) ruled interventions should continue. When the G77 and China challenged that ruling, chair Chruszczow called for a vote.

There are no formal records, and the SBI report omits any mention of it. But according to both the Earth Negotiations Bulletin and the Third World Network (p.49), abstentions were very widespread. The chair’s ruling stood and debate continued. It is likely that many delegations simply did not know what to do, so rare is the occurrence of voting.

Ironically, the debate was about a proposed new agenda item tabled by the Russian Federation, precisely on decision-making under the climate change regime.

There is one occasion when delegates did formally vote in the COP process, and on a decision with major substantive implications, but without reference to any rule.

This was at COP1 in Berlin, to decide on the permanent location of the secretariat. To overcome political sensitivities raging around the rules of procedure at the time, the exercise was labelled an “informal confidential survey”, rather than a vote.

Chair Estrada insisted it was “not a decision or a vote”, just a way of gauging preferences. But it was to all intents and purposes a secret ballot – and it did lead to a decision.

Three rounds of balloting eliminated the candidate cities of Montevideo in Uruguay, then Toronto in Canada, then Geneva in Switzerland, to leave Bonn in Germany victorious. This was, however, an isolated case that has not been repeated.

An added complication to decision-making in the climate regime is the absence of any operational definition of consensus.

Based on widespread practice elsewhere in the UN system, the term is generally taken to mean that there are no stated objections to a proposed decision. This understanding is included in the 2017 UNFCCC handbook for presiding officers, and echoes the custom whereby presidents and chairs, upon adopting a decision in plenary, bang their gavel and declare “I hear no objections, it is so decided”.

However, there is still ample room for interpretation. For example, can one objecting country really veto a decision that all other 197 parties want to see passed? This would equate consensus with unanimity, which many would contest. But if consensus does not equal unanimity, where does one draw the line? What if two countries are objecting, or even three? Does it matter who the countries are?

The history of the climate regime provides no simple answers, except to confirm that consensus is a messy process.

Challenging consensus

Challenges to consensus have produced different outcomes at different key moments in the negotiations.

The UNFCCC itself was adopted with a small handful of countries (mainly OPEC, plus Malaysia) waving their country nameplates in the air to raise objections. So was the Berlin Mandate, which launched negotiations on the Kyoto Protocol at COP1. Reservations were lodged to both documents.

At COP15 in Copenhagen in 2009, six countries declared their express opposition to the Copenhagen Accord, triggering the most dramatic plenary scenes ever seen in the climate negotiations, and preventing the document’s formal adoption.

The following year, in Cancún in Mexico, COP16 president Patricia Espinosa overruled Bolivia’s objection to the Cancún Agreements, declaring that “consensus does not mean unanimity… one delegation does not have the right to veto”. Two years later, in Doha in Qatar, COP18 president Al-Attiyah gavelled through the Doha Amendment to the Kyoto Protocol, ignoring an unmistakable request for the floor from Russia, supported by Belarus and Ukraine. In Paris in December 2015, COP21 president Laurent Fabius declared the Paris Agreement without acknowledging Nicaragua’s request to speak.

At COP24 in Katowice in Poland in 2018, three countries (Russia, Saudi Arabia and the US) refused to “welcome” the IPCC 1.5C special report, blocking the text. In Glasgow in 2021, language calling for the “phaseout” of coal was changed to “phase down” after a last-minute plenary huddle in response to objections principally from China, India, and South Africa. This provoked an outcry from Switzerland among others.

These differing outcomes and interpretations suggest consensus decision-making is an art, not a science. If nothing else, its ambiguous definition and reliance on the particular interpretation adopted by the chair generates far more uncertainty and potential for procedural dispute than if a voting rule could be invoked.

Unresolved items

“Adoption of the rules of procedure” – COP agenda sub-item 2(b) – is now the longest standing unresolved item on the COP agenda. Every year, the presidency undertakes to hold consultations on it, but these have now become almost perfunctory, with little expectation of progress.

There have occasionally been more serious moves to break the deadlock. At COP2 in 1996 in Geneva, the Zimbabwean COP presidency convened consultations that got as far as drawing up a compilation of options for rule 42.

This compilation included alternatives, for example, a seven-eighths supermajority. But countries maintained their positions at the following COP3 in Kyoto, and the deadlock continued.

In Durban, South Africa at COP17 in 2011, Papua New Guinea and Mexico made a concerted effort to resolve the impasse, in the wake of the highly-charged plenary dramas of Copenhagen and Cancún.

Their proposal took a novel approach: rather than trying to adopt the rules of procedure – which would require consensus – Papua New Guinea and Mexico proposed to amend the Convention itself, which could be done by a three-quarters majority, to introduce a voting rule.

The proposal had its challenges, notably that governments would have to individually ratify the amendment, potentially creating a confusing mosaic of parties and non-parties. But it did present a possible way forward that lawyers and negotiators could work with.

However, despite two rounds of extensive consultations at COP11 and COP12, the proposal never mustered sufficient support to progress. The agenda item under which it was considered – “proposal from Papua New Guinea and Mexico to amend articles 7 and 18 of the Convention” – remains on the provisional agenda to this day, although in abeyance (not discussed) since 2018.

There have been other attempts at a broader discussion of decision-making procedures. Following its overruling in Doha, the Russian Federation in 2013 insisted that procedural and legal issues relating to decision-making be subject to full-scale review, prompting the agenda fight at SBI38 discussed above.

After paralysing the SBI for an entire session, the issue was eventually added as a sub-item to the agenda of the subsequent Warsaw COP19. But little has come of it. Consultations on the sub-item are held every year but, like those on the adoption of the rules of procedure, have become purely a formality.

As discussed above therefore, there are three possible avenues for normalising decision-making rules on the COP agenda: sub-item 2(b) on adoption of the rules of procedure, the Papua New Guinea and Mexico proposal and the sub-item on decision-making under the UNFCCC process.

None of these options are subject to any serious consideration at present.

The main conclusion to be drawn from this, and from the extreme reluctance of parties to vote even on procedural matters, is that the consensus decision-making practice has, over time, become deeply entrenched in the climate regime.

The impact of consensus

What has been the impact of the consensus imperative on the climate regime? In the end, the absence of a voting rule did not prevent adoption of the key sets of commitments that built on the UNFCCC: the Kyoto Protocol, the Paris Agreement and their operational rulebooks.

Nonetheless, many would argue that consensus decision-making has led to slower, more incremental progress than under a last resort voting rule. However it is defined or interpreted, requiring consensus is a much more onerous bar to decision-making than a two-thirds, three-quarters or even seven-eighths voting majority would be.

Over the years, countless decisions have been abandoned, watered down or deferred to the next negotiating session because of a very small handful of objections.

At the opening plenary of COP27 in Sharm El Sheikh in 2022, the representative of Bangladesh argued that consensus was leading to “lowest common denominator” outcomes.

He added that “what we agree is going to be so weak, so ineffective, that it is not going to be anywhere near [meeting] the challenges of today”.

In the run-up to COP28 in Dubai in the United Arab Emirates in 2023, former US vice-president Al Gore denounced the absence of a voting rule, and the greater leverage this gives to obstructionists, as “absurd, ridiculous and offensive”.

The COP28 “UAE consensus” did not clearly call for the fossil fuel phaseout needed to limit warming to 1.5C, which may pay testimony to the limitations of consensus decision-making.

This is especially so if a very stringent interpretation of consensus is applied, in which, according to UNFCCC executive secretary Simon Steill, “all Parties must agree on every word, every comma, every full stop”.

With the entry into force of the Paris Agreement and adoption of its rulebook, the role of the COP is arguably increasingly shifting towards “political signalling”: sending out high-level messages to economic and political decision-makers of all kinds, on the direction, ambition and pace of global decarbonisation.

This underlines the need for COP decisions that are strong, unequivocal and aligned with the science. As such, it raises questions about the efficacy of consensus driven decision-making, and whether a “last resort” voting rule should be adopted for the climate change regime.

The Mexico and Papua New Guinea proposal demonstrated that creative legal options can be brought to the table. All that is needed – as ever in the climate space – is political will.

The post Guest post: The challenge of consensus decision-making in UN climate negotiations appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Guest post: The challenge of consensus decision-making in UN climate negotiations

Greenhouse Gases

Permitting reform: A major key to cutting climate pollution

Permitting reform: A major key to cutting climate pollution

By Dana Nuccitelli, CCL Research Coordinator

Permitting reform has emerged as the biggest and most important clean energy and climate policy area in the 119th Congress (2025-2026).

To make sure every CCL volunteer understands the opportunities and challenges ahead, CCL Vice President of Government Affairs Jennifer Tyler and I recently provided two trainings about the basics of permitting reform and understanding the permitting reform landscape.

These first introductory trainings set the stage for the rest of an ongoing series, which will delve into the details of several key permitting reform topics that CCL is engaging on. Read on for a recap of the first two trainings and a preview of coming attractions.

Permitting reform basics

Before diving into the permitting reform deep end, we need to first understand the fundamentals of the topic: what is “permitting”? What problems are we trying to solve with permitting reform? Why is it a key climate solution?

In short, a permit is a legal authorization issued by a government agency (federal and/or state and/or local) that allows a specific activity or project to proceed under certain defined conditions. The permitting process ensures that public health, safety, and the environment are protected during the construction and operation of the project.

But the permitting process can take a long time, and in some cases it’s taking so long that it’s unduly slowing down the clean energy transition. “Permitting reform” seeks to make the process more efficient while still ensuring that public health, safety, and the environment are protected.

There are a lot of factors involved in the permitting reform process, including environmental laws, limitations on lawsuits, and measures to expedite the building of electrical transmission lines that are key for expanding the capacity of America’s aging electrical grid in order to allow us to connect more clean energy and meet our energy affordability and security and climate needs.

But if we can succeed in passing a good, comprehensive permitting reform package through Congress, it could unlock enough climate pollution reductions to offset what we lost from this year’s rollback of the Inflation Reduction Act’s clean energy investments. Permitting reform is the big climate policy in the current session of Congress.

Understanding the permitting reform landscape

In the second training of this series, we sought to understand the players and the politics in the permitting reform space, learn about the challenges involved, and explore CCL’s framework and approach for weighing in on this policy topic.

Permitting reform has split some traditional alliances along two differing theories about how to best address climate change. Some groups with a theory of change relying on using permitting and lawsuits to slow and stop fossil fuel infrastructure are least likely to be supportive of a permitting reform effort. Groups like CCL that recognize the importance of quickly building lots of clean, affordable energy infrastructure are more supportive of permitting reform measures.

The subject has created some strange bedfellows, because clean energy and fossil fuel companies and organizations all want efficient permitting for their projects, and hence all tend to support permitting reform. For CCL, the key question is whether a comprehensive permitting reform package will be a net benefit to clean energy or the climate — and that’s what we’re working toward.

The two major political parties also have different priorities when it comes to permitting reform. Republicans tend to view it through a lens of reducing government red tape, ensuring that laws and regulations are only used for their intended purpose, and achieving energy affordability and security. Democrats prioritize building clean energy faster to slow climate change, addressing energy affordability, and protecting legacy environmental laws and community engagement.

As we discussed in the training, there are a number of key concepts that will require compromise from both sides of the aisle in order to reach a durable bipartisan permitting reform agreement. We’ll delve into the details of these in these upcoming trainings:

The Challenge of Energy Affordability and Security

First, with support from CCL’s Electrification Action Team, on February 5 I’ll examine what’s behind rising electricity rates and energy insecurity in the U.S. and how we can solve these problems. Electrification is a key climate solution in the transition to clean energy sources. But electricity rates are rising fast and face surging demand from artificial intelligence data centers. Permitting reform can play a key role in addressing these challenges.

Transmission Reform and Key Messages

Insufficient electrical transmission capacity is acting as a bottleneck slowing down the deployment of new clean energy sources in the U.S. Reforming cumbersome transmission permitting processes could unlock billions of tons of avoided climate pollution while improving America’s energy security and affordability. In this training on March 5, Jenn and I will dive into the details of the key clean energy and climate solution that is transmission reform, and the key messages to use when lobbying our members of Congress.

Clean energy projects often encounter long, complex permitting steps that slow construction and raise costs. Practical permitting reforms can help ensure that good projects move forward faster while upholding environmental and community protections. In this training on March 19, Jenn and I will examine permitting reforms to build energy infrastructure faster, some associated tensions and compromises that they may involve, and key messages for congressional offices.

Presidents from both political parties have taken steps to interfere with the permitting of certain types of energy infrastructure that they oppose. These executive actions create uncertainty that inhibits the development of new energy sources in the United States. For this reason, ensuring fair permitting certainty is a key aspect of permitting reform that enjoys bipartisan support. In this training on April 2, Jenn and I will discuss how Congress can ensure certainty in a permitting reform package, and key messages for congressional offices.

Community Engagement and Key Messages

It’s important for energy project developers to engage local communities in order to address any local concerns and adverse impacts that may arise from new infrastructure projects. But it’s also important to strike a careful balance such that community input can be heard and addressed in a timely manner without excessively slowing new clean energy project timelines. In this training on May 7, Jenn and I will examine how community engagement may be addressed in the permitting reform process, and key messages for congressional offices.

We look forward to nerding out with you in these upcoming advanced and important permitting reform trainings!

Want to take action now? Use our online action tool to call Congress and encourage them to work together on comprehensive permitting reform.

The post Permitting reform: A major key to cutting climate pollution appeared first on Citizens' Climate Lobby.

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 30 January 2026: Fire and ice; US formally exits Paris; Climate image faux pas

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Fire and ice

OZ HEAT: The ongoing heatwave in Australia reached record-high temperatures of almost 50C earlier this week, while authorities “urged caution as three forest fires burned out of control”, reported the Associated Press. Bloomberg said the Australian Open tennis tournament “rescheduled matches and activated extreme-heat protocols”. The Guardian reported that “the climate crisis has increased the frequency and severity of extreme weather events, including heatwaves and bushfires”.

WINTER STORM: Meanwhile, a severe winter storm swept across the south and east of the US and parts of Canada, causing “mass power outages and the cancellation of thousands of flights”, reported the Financial Times. More than 870,000 people across the country were without power and at least seven people died, according to BBC News.

COLD QUESTIONED: As the storm approached, climate-sceptic US president Donald Trump took to social media to ask facetiously: “Whatever happened to global warming???”, according to the Associated Press. There is currently significant debate among scientists about whether human-caused climate change is driving record cold extremes, as Carbon Brief has previously explained.

Around the world

- US EXIT: The US has formally left the Paris Agreement for the second time, one year after Trump announced the intention to exit, according to the Guardian. The New York Times reported that the US is “the only country in the world to abandon the international commitment to slow global warming”.

- WEAK PROPOSAL: Trump officials have delayed the repeal of the “endangerment finding” – a legal opinion that underpins federal climate rules in the US – due to “concerns the proposal is too weak to withstand a court challenge”, according to the Washington Post.

- DISCRIMINATION: A court in the Hague has ruled that the Dutch government “discriminated against people in one of its most vulnerable territories” by not helping them to adapt to climate change, reported the Guardian. The court ordered the Dutch government to set binding targets within 18 months to cut greenhouse gas emissions in line with the Paris Agreement, according to the Associated Press.

- WIND PACT: 10 European countries have agreed a “landmark pact” to “accelerate the rollout of offshore windfarms in the 2030s and build a power grid in the North Sea”, according to the Guardian.

- TRADE DEAL: India and the EU have agreed on the “mother of all trade deals”, which will save up to €4bn in import duty, reported the Hindustan Times. Reuters quoted EU officials saying that the landmark trade deal “will not trigger any changes” to the bloc’s carbon border adjustment mechanism.

- ‘TWO-TIER SYSTEM’: COP30 president André Corrêa do Lago believes that global cooperation should move to a “two-speed system, where new coalitions lead fast, practical action alongside the slower, consensus-based decision-making of the UN process”, according to a letter published on Tuesday, reported Climate Home News.

$2.3tn

The amount invested in “green tech” globally in 2025, marking a new record high, according to Bloomberg.

Latest climate research

- Including carbon emissions from permafrost thaw and fires reduces the remaining carbon budget for limiting warming to 1.5C by 25% | Communications Earth & Environment

- The global population exposed to extreme heat conditions is projected to nearly double if temperatures reach 2C | Nature Sustainability

- Polar bears in Svalbard – the fastest-warming region on Earth – are in better condition than they were a generation ago, as melting sea ice makes seal pups easier to reach | Scientific Reports

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

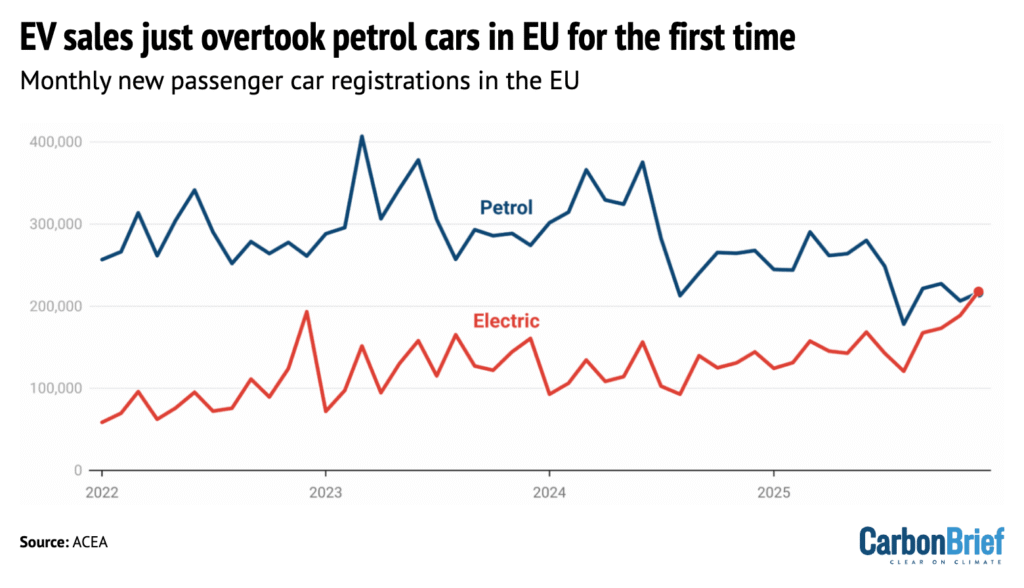

Sales of electric vehicles (EVs) overtook standard petrol cars in the EU for the first time in December 2025, according to new figures released by the European Automobile Manufacturers’ Association (ACEA) and covered by Carbon Brief. Registrations of “pure” battery EVs reached 217,898 – up 51% year-on-year from December 2024. Meanwhile, sales of standard petrol cars in the bloc fell 19% year-on-year, from 267,834 in December 2024 to 216,492 in December 2025, according to the analysis.

Spotlight

Looking at climate visuals

Carbon Brief’s Ayesha Tandon recently chaired a panel discussion at the launch of a new book focused on the impact of images used by the media to depict climate change.

When asked to describe an image that represents climate change, many people think of polar bears on melting ice or devastating droughts.

But do these common images – often repeated in the media – risk making climate change feel like a far-away problem from people in the global north? And could they perpetuate harmful stereotypes?

These are some of the questions addressed in a new book by Prof Saffron O’Neill, who researches the visual communication of climate change at the University of Exeter.

“The Visual Life of Climate Change” examines the impact of common images used to depict climate change – and how the use of different visuals might help to effect change.

At a launch event for her book in London, a panel of experts – moderated by Carbon Brief’s Ayesha Tandon – discussed some of the takeaways from the book and the “dos and don’ts” of climate imagery.

Power of an image

“This book is about what kind of work images are doing in the world, who has the power and whose voices are being marginalised,” O’Neill told the gathering of journalists and scientists assembled at the Frontline Club in central London for the launch event.

O’Neill opened by presenting a series of climate imagery case studies from her book. This included several examples of images that could be viewed as “disempowering”.

For example, to visualise climate change in small island nations, such as Tuvalu or Fiji, O’Neill said that photographers often “fly in” to capture images of “small children being vulnerable”. She lamented that this narrative “misses the stories about countries like Tuvalu that are really international leaders in climate policy”.

Similarly, images of power-plant smoke stacks, often used in online climate media articles, almost always omit the people that live alongside them, “breathing their pollution”, she said.

During the panel discussion that followed, panellist Dr James Painter – a research associate at the Reuters Institute for the Study of Journalism and senior teaching associate at the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute – highlighted his work on heatwave imagery in the media.

Painter said that “the UK was egregious for its ‘fun in the sun’ imagery” during dangerous heatwaves.

He highlighted a series of images in the Daily Mail in July 2019 depicting people enjoying themselves on beaches or in fountains during an intense heatwave – even as the text of the piece spoke to the negative health impacts of the heatwave.

In contrast, he said his analysis of Indian media revealed “not one single image of ‘fun in the sun’”.

Meanwhile, climate journalist Katherine Dunn asked: “Are we still using and abusing the polar bear?”. O’Neill suggested that polar bear images “are distant in time and space to many people”, but can still be “super engaging” to others – for example, younger audiences.

Panellist Dr Rebecca Swift – senior vice president of creative at Getty images – identified AI-generated images as “the biggest threat that we, in this space, are all having to fight against now”. She expressed concern that we may need to “prove” that images are “actually real”.

However, she argued that AI will not “win” because, “in the end, authentic images, real stories and real people are what we react to”.

When asked if we expect too much from images, O’Neill argued “we can never pin down a social change to one image, but what we can say is that images both shape and reflect the societies that we live in”. She added:

“I don’t think we can ask photos to do the work that we need to do as a society, but they certainly both shape and show us where the future may lie.”

Watch, read, listen

UNSTOPPABLE WILDFIRES: “Funding cuts, conspiracy theories and ‘powder keg’ pine plantations” are making Patagonia’s wildfires “almost impossible to stop”, said the Guardian.

AUDIO SURVEY: Sverige Radio has published “the world’s, probably, longest audio survey” – a six-hour podcast featuring more than 200 people sharing their questions around climate change.

UNDERSTAND CBAM: European thinktank Bruegel released a podcast “all about” the EU’s carbon adjustment border mechanism, which came into force on 1 January.

Coming up

- 1 February: Costa Rican general election

- 3 February: UN Environment Programme Adaptation Fund Climate Innovation Accelerator report launch, Online

- 2-8 February: Intergovernmental Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES) 12th plenary, Manchester, UK

Pick of the jobs

- Climate Central, climate data scientist | Salary: $85,000-$92,000. Location: Remote (US)

- UN office to the African Union, environmental affairs officer | Salary: Unknown. Location: Addis Ababa, Ethiopia

- Google Deepmind, research scientist in biosphere models | Salary: Unknown. Location: Zurich, Switzerland

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 30 January 2026: Fire and ice; US formally exits Paris; Climate image faux pas appeared first on Carbon Brief.

DeBriefed 30 January 2026: Fire and ice; US formally exits Paris; Climate image faux pas

Greenhouse Gases

Factcheck: What it really costs to heat a home in the UK with a heat pump

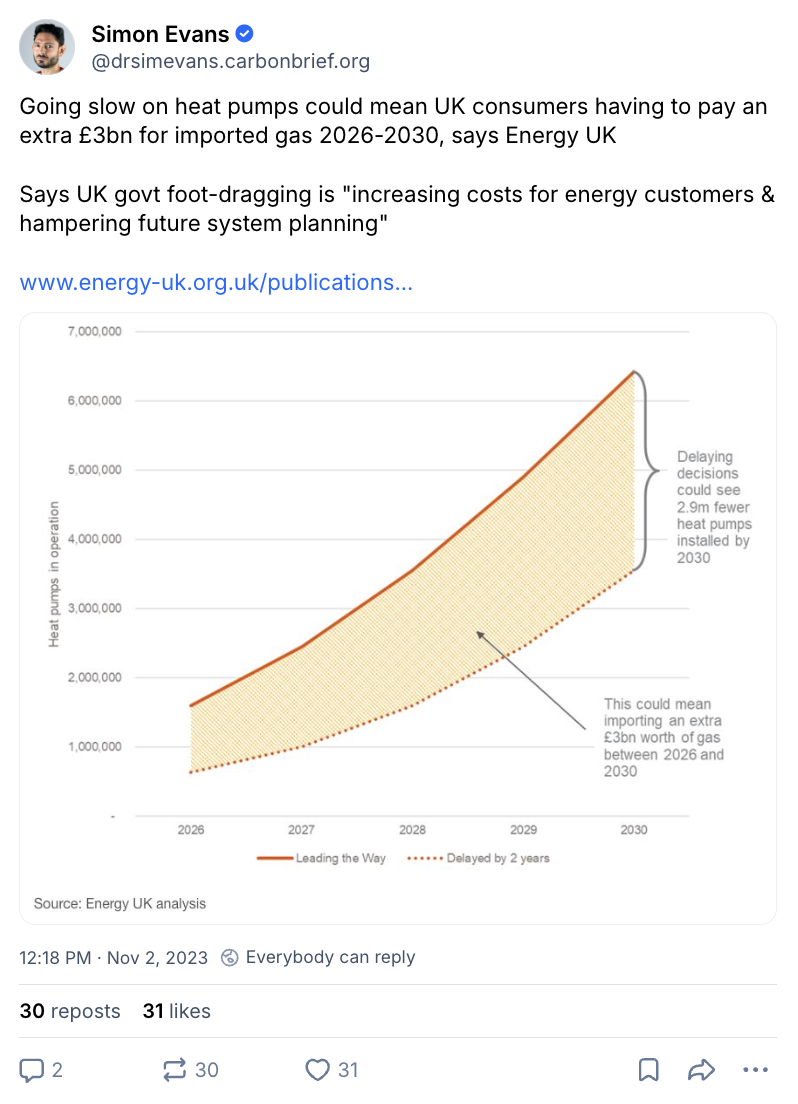

Electric heat pumps are set to play a key role in the UK’s climate strategy, as well as cutting the nation’s reliance on imported fossil fuels.

Heat pumps took centre-stage in the UK government’s recent “warm homes plan”, which said that they could also help cut household energy bills by “hundreds of pounds” a year.

Similarly, innovation agency Nesta estimates that typical households could cut their annual energy bills nearly £300 a year, by switching from a gas boiler to a heat pump.

Yet there has been widespread media coverage in the Times, Sunday Times, Daily Express, Daily Telegraph and elsewhere of a report claiming that heat pumps are “more expensive” to run.

The report is from the Green Britain Foundation set up by Dale Vince, owner of energy firm Ecotricity, who campaigns against heat pumps and invests in “green gas” as an alternative.

One expert tells Carbon Brief that Vince’s report is based on “flimsy data”, while another says that it “combines a series of worst-case assumptions to present an unduly pessimistic picture”.

This factcheck explains how heat pumps can cut bills, what the latest data shows about potential savings and how this information was left out of the report from Vince’s foundation.

How heat pumps can cut bills

Heat pumps use electricity to move heat – most commonly from outside air – to the inside of a building, in a process that is similar to the way that a fridge keeps its contents cold.

This means that they are highly efficient, adding three or four units of heat to the house for each unit of electricity used. In contrast, a gas boiler will always supply less than one unit of heat from each unit of gas that it burns, because some of the energy is lost during combustion.

This means that heat pumps can keep buildings warm while using three, four or even five times less energy than a gas boiler. This cuts fossil-fuel imports, reducing demand for gas by at least two-fifths, even in the unlikely scenario that all of the electricity they need is gas-fired.

Since UK electricity supplies are now the cleanest they have ever been, heat pumps also cut the carbon emissions associated with staying warm by around 85%, relative to a gas boiler.

Heat pumps are, therefore, the “central” technology for cutting carbon emissions from buildings.

While heat pumps cost more to install than gas boilers, the UK government’s recent “warm homes plan” says that they can help cut energy bills by “hundreds of pounds” per year.

Similarly, Nesta published analysis showing that a typical home could cut its annual energy bill by £280, if it replaces a gas boiler with a heat pump, as shown in the figure below.

Nesta and the government plan say that significantly larger savings are possible if heat pumps are combined with other clean-energy technologies, such as solar and batteries.

Both the government and Nesta’s estimates of bill savings from switching to a heat pump rely on relatively conservative assumptions.

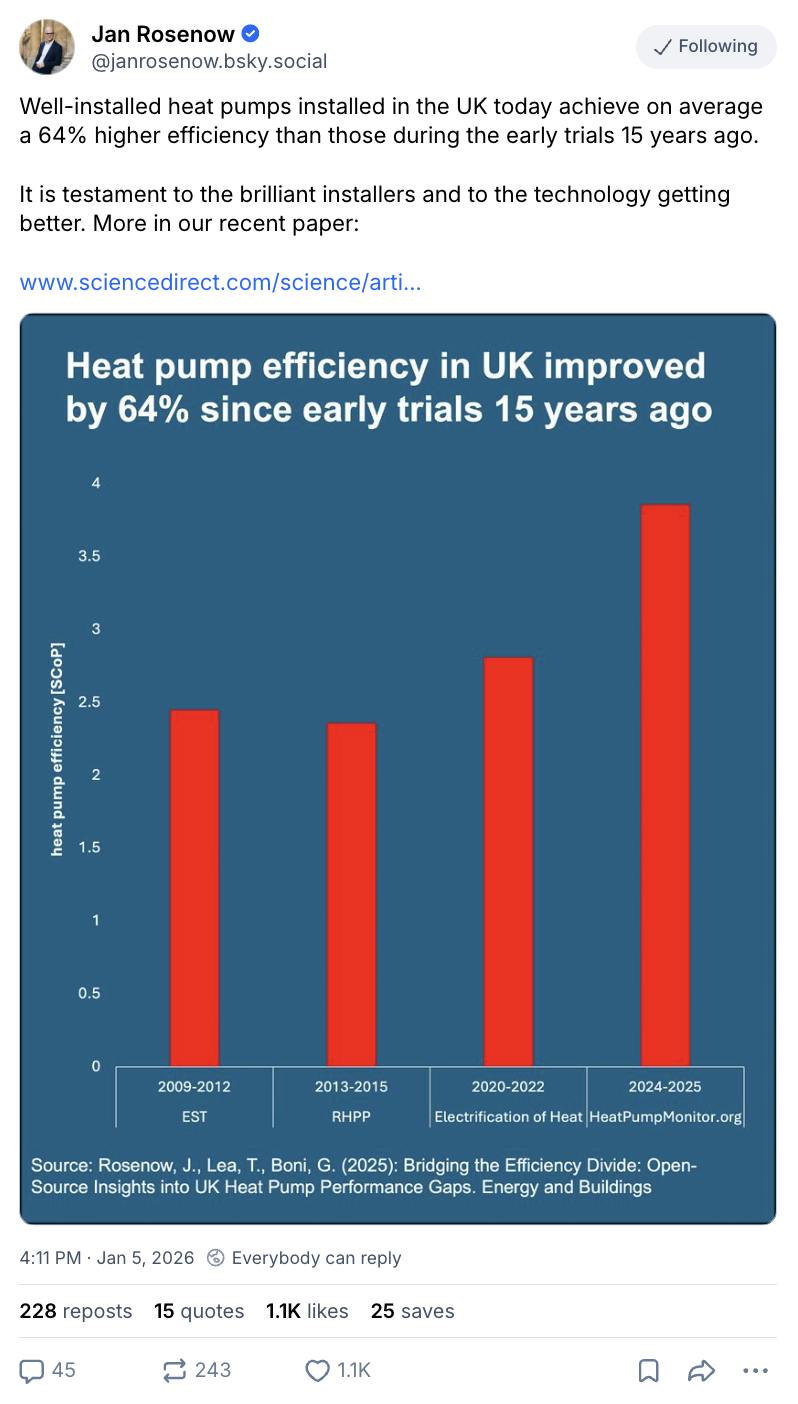

Specifically, the government assumes that a heat pump will deliver 2.8 units of heat for each unit of electricity, on average. This is known as the “seasonal coefficient of performance” (SCoP).

This figure is taken from the government-backed “electrification of heat” trial, which ran during 2020-2022 and showed that heat pumps are suitable for all building types in the UK.

(The Green Britain Foundation report and Vince’s quotes in related coverage repeat a number of heat pump myths, such as the idea that they do not perform well in older properties and require high levels of insulation.)

Nesta assumes a slightly higher SCoP of 3.0, says Madeleine Gabriel, the organisation’s director of sustainable future. (See below for more on what the latest data says about SCoP in recent installations.)

Both the government and Nesta assume that a home with a heat pump would disconnect from the gas grid, meaning that it would no longer need to pay the daily “standing charge” for gas. This currently amounts to a saving of around £130 per year.

Finally, they both consider the impact of a home with a heat pump using a “smart tariff”, where the price of electricity varies according to the time of day.

Such tariffs are now widely available from a variety of energy suppliers and many have been designed specifically for homes that have a heat pump.

Such tariffs significantly reduce the average price for a unit of electricity. Government survey data suggests that around half of heat-pump owners already use such tariffs.

This is important because on the standard rates under the price cap set by energy regulator Ofgem, each unit of electricity costs more than four times as much as a unit of gas.

The ratio between electricity and gas prices is a key determinant of the size and potential for running-cost savings with a heat pump. Countries with a lower electricity-to-gas price ratio consistently see much higher rates of heat-pump adoption.

(Decisions taken by the UK government in its 2025 budget mean that the electricity-to-gas ratio will fall from April, but current forecasts suggest it will remain above four-to-one.)

In contrast, Vince’s report assumes that gas boilers are 90% efficient, whereas data from real homes suggests 85% is more typical. It also assumes that homes with heat pumps remain on the gas grid, paying the standing charge, as well as using only a standard electricity tariff.

Prof Jan Rosenow, energy programme leader at the University of Oxford’s Environmental Change Institute, tells Carbon Brief that Vince’s report uses “worst-case assumptions”. He says:

“This report cherry-picks assumptions to reach a predetermined conclusion. Most notably, it assumes a gas boiler efficiency of 90%, which is significantly higher than real-world performance…Taken together, the analysis combines a series of worst-case assumptions to present an unduly pessimistic picture.”

Similarly, Gabriel tells Carbon Brief that Vince’s report is based on “flimsy data”. She explains:

“Dale Vince has drawn some very strong conclusions about heat pumps from quite flimsy data. Like Dale, we’d also like to see electricity prices come down relative to gas, but we estimate that, from April, even a moderately efficient heat pump on a standard tariff will be cheaper to run than a gas boiler. Paired with a time-of-use tariff, a heat pump could save £280 versus a boiler and adding solar panels and a battery could triple those savings.”

What the latest data shows about bill savings

The efficiency of heat-pump installations is another key factor in the potential bill savings they can deliver and, here, both the government and Vince’s report take a conservative approach.

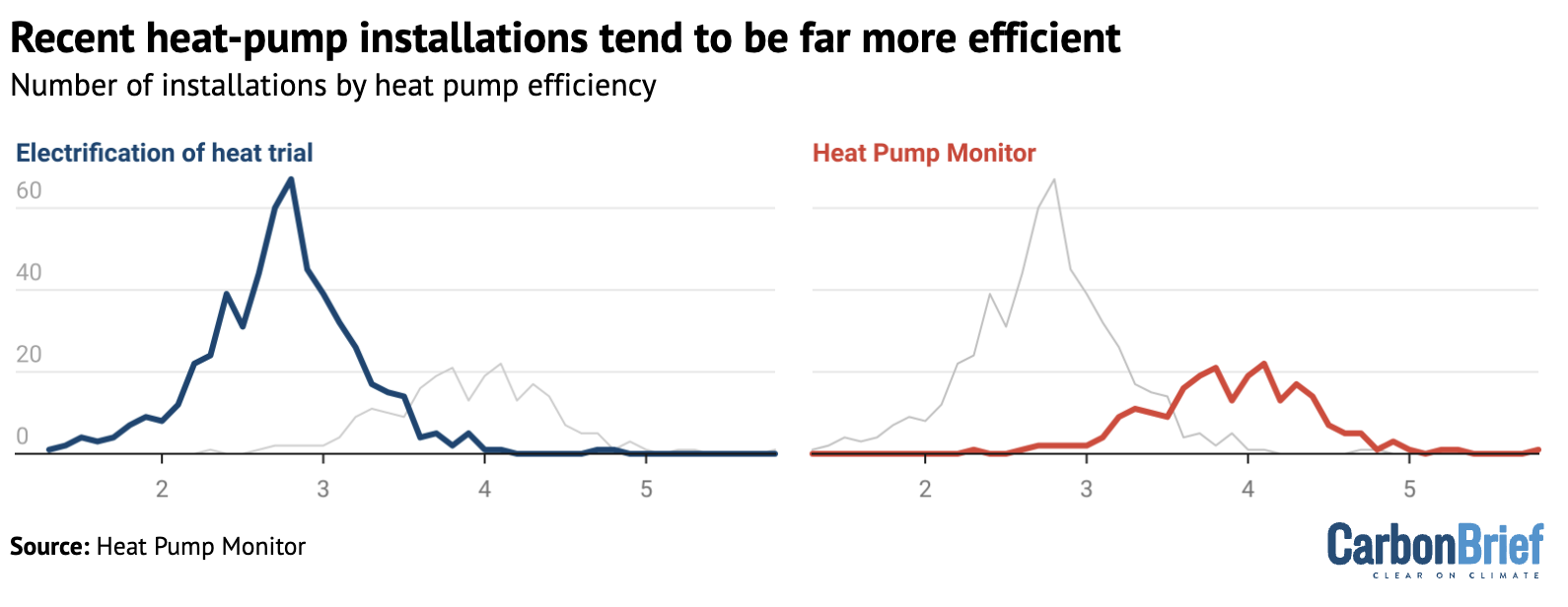

They rely on the “electrification of heat” trial data to use an efficiency (SCoP) of 2.8 for heat pumps. However, Rosenow says that recent evidence shows that “substantially higher efficiencies are routinely available”, as shown in the figure below.

Detailed, real-time data on hundreds of heat pump systems around the UK is available via the website Heat Pump Monitor, where the average efficiency – a SCoP of 3.9 – is much higher.

Homes with such efficient heat-pump installations would see even larger bill savings than suggested by the government and Nesta estimates.

Academic research suggests that there are simple and easy-to-implement reasons why these systems achieve much higher efficiency levels than in the electrification of heat trial.

Specifically, it shows that many of the systems in the trial have poor software settings, which means they do not operate as efficiently as their heat pump hardware is capable of doing.

The research suggests that heat pump installations in the UK have been getting more and more efficient over time, as engineers become increasingly familiar with the technology.

It indicates that recently installed heat pumps are 64% more efficient than those in early trials.

Notably, the Green Britain Foundation report only refers to the trial data from the electrification of heat study carried out in 2020-22 and the even earlier “renewable heat premium package” (RHPP). This makes a huge difference to the estimated running costs of a heat pump.

Carbon Brief analysis suggests that a typical household could cut its annual energy bills by nearly £200 with a heat pump – even on a standard electricity tariff – if the system has a SCoP of 3.9.

The savings would be even larger on a smart heat-pump tariff.

In contrast, based on the oldest efficiency figures mentioned in the Green Britain Foundation report, a heat pump could increase annual household bills by as much as £200 on a standard tariff.

To support its conclusions, the report also includes the results of a survey of 1,001 heat pump owners, which, among other things, is at odds with government survey data. The report says “66% of respondents report that their homes are more expensive to heat than the previous system”.

There are several reasons to treat these findings with caution. The survey was carried out in July 2025 and some 45% of the heat pumps involved were installed between 2021-23.

This is a period during which energy prices surged as a result of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and the resulting global energy crisis. Energy bills remain elevated as a result of high gas prices.

The wording of the survey question asks if homes are “more or less expensive to heat than with your previous system” – but makes no mention of these price rises.

The question does not ask homeowners if their bills are higher today, with a heat pump, than they would have been with the household’s previous heating system.

If respondents interpreted the question as asking whether their bills have gone up or down since their heat pump was installed, then their answers will be confounded by the rise in prices overall.

There are a number of other seemingly contradictory aspects of the survey that raise questions about its findings and the strong conclusions in the media coverage of the report.

For example, while only 15% of respondents say it is cheaper to heat their home with a heat pump, 49% say that one of the top three advantages of the system is saving money on energy bills.

In addition, 57% of respondents say they still have a boiler, even though 67% say they received government subsidies for their heat-pump installation. It is a requirement of the government’s boiler upgrade scheme (BUS) grants that homeowners completely remove their boiler.

The government’s own survey of BUS recipients finds that only 13% of respondents say their bills have gone up, whereas 37% say their bills have gone down, another 13% say they have stayed the same and 8% thought that it was too early to say.

The post Factcheck: What it really costs to heat a home in the UK with a heat pump appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Factcheck: What it really costs to heat a home in the UK with a heat pump

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits