Lately I’ve been speaking with a lot of big companies and universities as part of Greenpeace’s gas campaign.

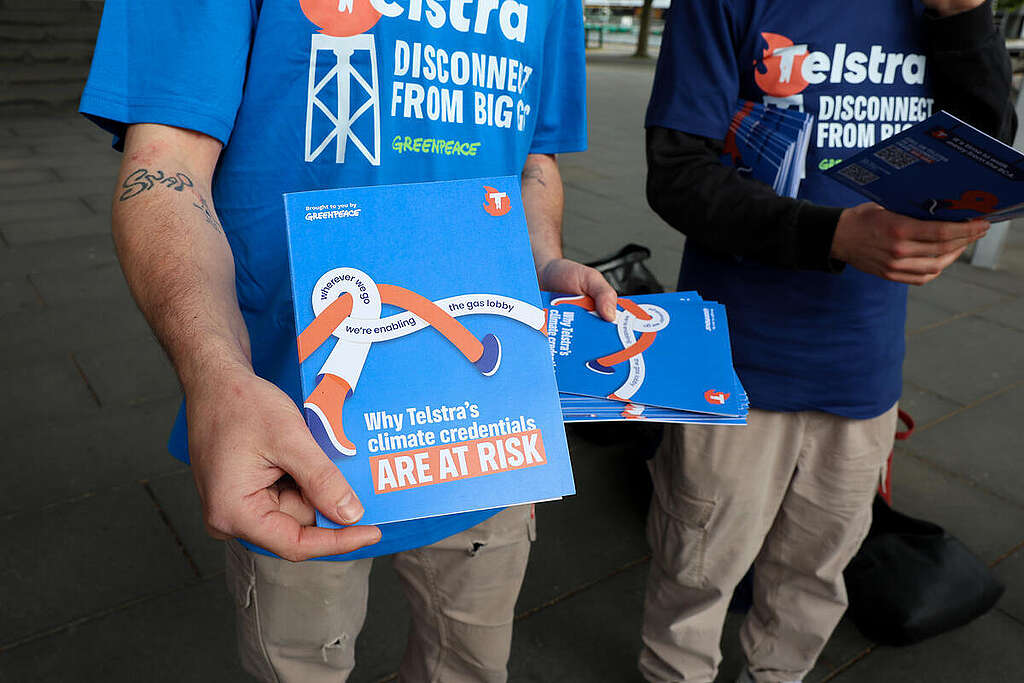

We’re urging brands like Telstra, Bupa, Woolworths, UTS, NAB and more to cancel their membership of the Business Council of Australia (BCA) – a powerful lobby group that’s been advocating for more dirty gas projects on their behalf.

Greenpeace is focused on these brands because they all claim to care about climate action and have made strong individual commitments to decarbonise their businesses. As a company committed to reducing emissions, you’d think that fossil fuel lobbying is counterproductive to those efforts – right?

These companies don’t think so. What I hear in meeting after meeting is a version of “that’s not my problem.”

But fossil fuel lobbying is their problem – and not just because it destroys their credibility on climate. Direct or indirect lobbying can bring legal, investor, reputational, and governance risk that companies need to be taking seriously.

Why indirect lobbying matters: the political influence of Industry Associations

Direct lobbying is when a corporation goes directly to the government, or whoever they are trying to influence and pushes their views. Indirect lobbying is when a corporation pays to be part of an Industry Association (also known as a peak body) which will do that lobbying on its behalf.

For a company, indirect lobbying via an Industry Association is often more influential than their own direct lobbying. Industry Associations like the BCA and Australian Energy Producers (AEP) have a big impact on shaping policy, through directly lobbying the government, being active in the media and advertising, and making political donations. Indeed this influence is the key reason why companies choose to become members in the first place – because they recognise that by presenting as a united voice, they can get more done than lobbying as one company.

When the BCA or AEP speak – the government listens. Prime Minister Albanese gave the keynote address at the BCA’s annual gala dinner earlier this year. And these groups are amongst the first to be consulted and receive briefings when the government is designing policy.

Examples of times industry association lobbying shaped government policy:

- Both the AEP and BCA made submissions to the government consultation on the Future Gas Strategy – with their key demands and narratives showing up many times in the government’s final strategy. This is the document setting the direction for the role of gas in Australia’s energy mix out to 2050 and beyond, but it reads more like Woodside’s Strategic Plan.

- The BCA and AEP were vocal advocates for the approval of Woodside’s North West Shelf Extension – arguing, in spite of their commitments to the Paris Agreement, that we need more gas. Not long after, the government approved the project.

- The BCA lobbied the government around the setting of its emissions reductions targets, arguing that a more ambitious target would cost too much. The government soon announced a weak target – far below what the science says is required to meet our international climate targets.

The BCA and AEP gain power from the fact that they claim to represent over a hundred large businesses, acting as spokespeople for their collective interests. The BCA and AEP rely on the brand recognition and reputation of their member companies, and in turn those companies benefit by having their views represented in parliament and the media.

Companies like Telstra, Commonwealth Bank and others may choose to look the other way – but refusing to acknowledge a problem doesn’t make it go away.

Legal risk of indirect lobbying that is misaligned with a company’s own climate commitments

When companies tell their customers and investors they have certain policies on climate change, it is their responsibility to ensure that their actions match the commitments they have made on paper.

So when a company says it is committed to the Paris Agreement, but then is part of an industry association which is lobbying for policies that are incompatible with the goals of the Paris Agreement, that could amount to what is known in legal terms as “misleading and deceptive conduct”. There is also a legal risk for board directors, who often don’t have oversight over what indirect fossil fuel lobbying a company is engaged in.

A specific example of this is the BCA and AEP’s lobbying for further gas expansion, when there is scientific consensus that expanding fossil fuels is incompatible with the goal of limiting warming to below 1.5C. As stated in this Climate Integrity report:

The “net zero by 2050” target is based upon the need to limit warming below 1.5°C to prevent further tipping points from being reached and then maintaining that temperature. Any net zero pledge that undermines this 1.5°C limit is self-contradictory and could in certain circumstances be viewed as misleading

In the eyes of the law, this applies not just to a company’s individual climate commitments – but also its indirect lobbying activities.

Investor risk of misaligned corporate lobbying

The Australasian Centre for Corporate Responsibility (ACCR) has outlined in depth the risks posed to a company’s investors from advocating on climate policy that is out of alignment with a company’s own policies and commercial interests.

Companies pay steep membership fees to be part of groups like the BCA and AEP. AGL for example paid $104,500 for its BCA membership in 2024. It could be considered a misuse of shareholder funds for a company to be a paying member of an industry association which does not represent its stated interests. In recent years investors have been doing more to hold companies to account for the activities of their industry associations.

In a report from over 5 years ago, ACCR explicitly identifies the core of the issue that still persists today:

There is often a significant difference between the formal policies of an industry association and the public advocacy that it undertakes. The most common example of this is companies that endorse the Paris Agreement while advocating for policies that are simply irreconcilable with its central objective: limiting global warming to 2ºC above pre-industrial temperatures. It is this fundamental disparity between policy and advocacy that poses the single largest risk to investors.

Companies that are part of these groups must take responsibility for their industry association lobbying that is out of alignment with the Paris Agreement and take note of the risks posed to investors.

What can you do to hold these brands accountable for their fossil fuel lobbying?

If you’re a member of the public:

- Greenpeace has created a Climate Credibility Scorecard, where we’ve ranked some of the most influential BCA members with strong climate commitments on what steps they’ve taken to distance themselves from the BCA’s lobbying for more dirty gas. This is a live resource that we’ll keep updating and adding more companies to, so keep checking back!

- You can email the CEOs of these companies using our easy tool and increase the pressure on them to act.

- Leave a message for Telstra’s leadership team here and urge them to quit the BCA. And help amplify our message on social media.

If you’re an employee of a company who is indirectly lobbying for fossil fuels:

- Check out this briefing for Telstra employees here (but the same tips apply to any company or university that is in the BCA or AEP!)

If you’re a member of an organisation or company considering partnering with one of these companies:

- Don’t take sponsorships from or offer speaking slots to companies in the BCA and AEP who aren’t walking the talk on climate. Prove that their reputation on climate is on the line.

The science is crystal clear: we can’t approve any new coal or gas projects if we want to avoid catastrophic climate impacts and limit global warming to 1.5C. We’re already feeling the impacts of climate change here in Australia and around the world – and the recent Climate Risk Assessment demonstrates just how bad things could get if we don’t urgently slash pollution from coal and gas now.

Until companies start actually taking responsibility for their fossil fuel lobbying – individual decarbonisation goals just aren’t going to cut it.

Will you join us and help hold these big brands to account?

Why indirect fossil fuel lobbying is everybody’s problem and big brands must be held accountable

Climate Change

Uganda may see lower oil revenues than expected as costs rise and demand falls

Uganda’s plan to use future revenues from its emerging oil industry to drive economic development may not work as expected, because evidence so far shows that the government’s effort to extract and export its crude oil may not produce the returns it is counting on, analysts have warned.

A new report by the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis (IEEFA) found that Uganda stands to benefit far less from oil production than previously projected, with revenues set to be half of earlier estimates if the world transitions away from fossil fuels on a path to reaching net zero emissions.

Uganda’s oil ambitions involve developing two oilfields on the shores of Lake Albert – Tilenga and Kingfisher – and constructing the 1,443-km East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP), with the aim of transporting 230,000 barrels of crude per day to Tanzania’s Tanga port for export.

Gas flaring soars in Niger Delta post-Shell, afflicting communities

Led by oil major TotalEnergies and China National Offshore Oil Company (CNOOC), alongside the Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC) and Tanzania Petroleum Development Corporation, the project was given the financial go-ahead in 2022.

Will Scargill, one of the IEEFA report’s authors, told an online launch this week that oil may have seemed a historically attractive option for Uganda but the benefits it could yield are very sensitive to major risks, including cost overruns around the project and in the refining sector, which it also plans to enter.

“The EACOP project is expected to cost much more than the original expectations, so it’s a major project risk in Uganda as well,” he said.

The start of oil production and exports through the East Africa pipeline had been expected by 2025 – nearly 20 years after commercially viable oil was first discovered in the country – but has now been delayed until late 2026 or 2027.

Meanwhile, the cost of construction – particularly for the EACOP part of the project – has continued to rise, reaching around $5.6 billion, a 55% increase from the $3.6 billion projected shortly before it got financial approval, the report said.

US tariffs, China’s EV boom to curb oil revenues

Beyond delays and cost overruns, “there’s the risk the impact of the accelerating shift away from fossil fuels will have on the oil market,” Scargill said.

The report said the most significant factors for the Ugandan oil industry – which are beyond its control – have been the reduced outlook for international trade spurred by recently imposed US tariffs and the growing uptake of electric vehicles (EVs), particularly in China – which has led to a peak in transport fuel demand and an expected peak in overall oil consumption by 2027.

The 2025 oil outlook from the International Energy Agency (IEA) shows that growth in global oil demand will fall significantly by the end of the decade before entering a decline, driven mainly by electrification in transport which will displace 5.4 million barrels per day of global oil demand by the end of the decade.

In addition, structural changes in global energy markets, including oil supply growth outside the OPEC+ bloc – a group of major oil-producing countries including Saudi Arabia and Russia that sets production quotas – particularly in the US, Brazil and Guyana, are lowering prices.

“It’s a particularly bad time to be taking single big bets on particular sectors that are linked to external markets,” said Matthew Huxham, a co-author of the IEEFA report.

To make matters worse, Uganda’s public finances have been weakened in the past decade by external shocks including higher US interest rates and commodity prices, resulting in downgrades of the country’s sovereign credit rating, he added.

“What that means is, generally speaking, there is less fiscal resilience to shocks,” Huxham said.

Lower global demand for oil would likely see lower prices, profits and revenues for the Ugandan government, the report authors said. In addition, a global shift to renewable energy would mean Uganda selling even fewer barrels into international markets.

All of these factors suggest that investment in Uganda’s oil industry “would unlikely be as transformational as expected” for its development, Scargill said.

Climate Home News reached out to the Uganda National Oil Company and EACOP but had not received a response at the time of publication.

Foreign investors to recover costs while Uganda faces risks

Uganda has invested a significant amount of government funds not only in the oil pipeline but also in supporting infrastructure such as a planned refinery. The report authors raised concerns about revenue-sharing agreements under which foreign investors are entitled to recover their costs first, taking a larger share of oil revenues in the early years of production.

IEEFA estimates that while TotalEnergies’ and CNOOC’s returns could fall by 25-34% as the world uses less oil and moves from fossil fuels to clean energy, Uganda’s expected revenues could decline by up to 53%.

Explainer: What is the petrodollar and why is it under pressure?

Uganda is pursuing a $4.5-billion oil refinery project in Hoima District, with the country’s oil company UNOC due to take a 40% stake. To finance part of this investment and other oil-related infrastructure, UNOC has secured a loan facility of up to $2 billion from commodity trader Vitol.

Under the deal, Vitol gains priority access to oil revenues, placing it ahead of the Ugandan government when money starts flowing in, the report said. The IEEFA analysts warn that this will likely displace or defer planned use of the revenues for other government spending on things like health, education and climate adaptation, especially if oil production and the refinery construction are delayed or profits disappoint.

“Even if the refinery project is on time and on budget, the refinery and loan repayments could consume 40% of Uganda’s oil revenues through 2032,” Scargill noted.

Pointing to recent cost overruns at oil refinery projects in Africa, the report authors said Nigeria’s

Dangote refinery ended up costing more than twice the original estimate – jumping from $9 billion to over $18 billion.

Climate action is “weapon” for security in unstable world, UN climate chief says

They said analysis shows the Uganda refinery will cost 25% more than planned, on top of an expected overrun of over 50% on the EACOP project, cutting the annual return rate to 10%.

“This means there is a high chance the project, by itself, will not make any money,” the report added.

Responding to the report, the StopEACOP coalition said the analysis confirms that beyond causing ongoing environmental harm and displacing hundreds of thousands, the project “does not make economic sense, especially for the host countries”.

They called on financial institutions, including Standard Bank, KCB Uganda, Stanbic Uganda, Afreximbank, and the Islamic Corporation for the Development of the Private Sector, which are backing the “controversial” EACOP project, “to seriously engage with the findings of the IEEFA reports and reconsider their support”.

Prioritise climate-resilient investments instead

In another report released alongside the one on oil project finances, IEEFA argued that Uganda could achieve stronger and more effective development outcomes by redirecting its scarce public resources towards climate-resilient, electrified industrialisation rather than doubling down on oil.

Uganda is among the countries most vulnerable to climate change, yet ranks low in readiness to cope with its impacts. The report authors urged the government to apply stricter criteria when deciding how to spend public funds, focusing on things like improving access to modern energy services and climate adaptation.

The IEEFA report recommended investments in off-grid and mini-grid solar electrification, agro-processing, cold storage, crop irrigation and better roads as lower-risk alternatives to investing in fossil fuels.

Africa records fastest-ever solar growth, as installations jump in 2025

Investments that take climate risks into account could also attract concessional climate finance and align with Uganda’s fourth National Development Plan and Just Transition Framework, the report said.

“They also take less long to construct, are easy to deploy, pay back over a shorter period and they also put less pressure on the system,” Huxham added.

The post Uganda may see lower oil revenues than expected as costs rise and demand falls appeared first on Climate Home News.

Uganda may see lower oil revenues than expected as costs rise and demand falls

Climate Change

Ugandans living near new oil pipeline let down by compensation programmes

Most Ugandans whose land and livelihoods were affected by the construction of the East African Crude Oil Pipeline (EACOP) are dissatisfied with training programmes provided by developers which were designed to stop them being left worse off, a survey has found.

The Africa Institute for Energy Governance (AFIEGO) asked 246 people in seven communities affected by the project for their views on the developers Resettlement Action Plan (RAP).

It found that while most affected households have received some form of support, most were dissatisfied with the quality of food security programmes and training on alternative vocations and financial literacy.

Dickens Kamugisha, AFIEGO’s CEO, said that while the Ugandan government claims it is developing the oil sector to create lasting value for everyone, this study shows that this is not the case especially for the people that were displaced for the project.

“They lost their land, were under-compensated and now an inadequate livelihood restoration programme is being implemented. Instead of creating lasting value for the project-affected people, the government and the EACOP company could create lasting poverty for the people”, he added.

EACOP is being built by a coalition led by the French company Total, along with China’s National Offshore Oil Corporation and Uganda and Tanzania’s state-owned oil companies.

The 1,400 km pipeline will take oil from Uganda’s Tilenga and Kingfisher oil fields through Tanzania to the East African coast, where the oil can be put on ships and exported.

Inadequate training

Nearly four-in-five of those surveyed described vocational training programmes, designed to give displaced people new professions like bakers, welders and soap makers, as inadequate. They cited short training periods, absentee trainers and limited hands-on learning.

One participant said he was trained in catering for four months in 2024. “I did not understand what I was taught. We were not learning most of the time”, he said.

The young man said that he only cooked once in the four months and that trainers told them that they would be sent home if they complained.

The financial literacy programme, aimed at training people to use their compensation wisely, was also described as inadequate by nearly four-fifths.

They said the training was only one day and was conducted by a commercial bank, which pushed them to open bank accounts rather than improving their money management practices.

“They were interested in business, and not in people learning”, one woman said, “no wonder when people got money, some married more women. The compensation was also too little!”

Not enough food

Those who were physically displaced by the pipeline or who lost more than a fifth of their land to it were supposed to be entitled to food assistance for up to a year or more.

While three-quarters of respondents received some food assistance, just a third said it was adequate. They complained that they did not understand why some people were getting food and others not.

There were also complaints about the quantity of beans, rice, cooking oil and salt provided, particularly from those with big families. One woman said her family of 30 used up the 4 kg of rice and beans in one meal.

An agricultural recovery programme aimed to help people transition but, while many confirmed receiving seeds, seedlings or fertilisers, they complained that the seeds were poor quality and distributed too late – after the rains – for crops to grow.

In Kyotera District, one participant recounted receiving 70 coffee seedlings, of which only 20 survived. “We were given very young coffee seedlings. They were also poor quality with some having no roots,” the participant said. “I watered those coffee seedlings, but they did not grow. They were poor quality!”

Some of the affected communities also complained about not getting the livelihood options they wanted, adding that those who wanted livestock were given seeds instead because they did not have a building to house the livestock.

On the other hand, the survey found that about two-thirds of affected people were satisfied with the distance between their homes and the pipeline. The third who were not satisfied said they feared accidents like oil spills and noise and dust pollution as the pipeline is built.

“I fear for my life,” said one man in Hoima, “the pipeline can burst, spill and affect us. We have also been told that the pipeline will be heated. The heat from the pipeline could affect our soils”.

The post Ugandans living near new oil pipeline let down by compensation programmes appeared first on Climate Home News.

Ugandans living near new oil pipeline let down by compensation programmes

Climate Change

Virginia House Passes Data Center Tax Exemption, With Conditions

New and existing data centers could continue receiving a break on the state’s retail sales and use tax, as long as they moved away from fossil fuels and tried to reduce energy usage.

RICHMOND, Va.—The Virginia House of Delegates on Tuesday passed legislation continuing billions of dollars in state tax exemptions for all qualifying new and existing data centers as long as they take a series of steps to move away from fossil fuels and transition to renewable energy.

Virginia House Passes Data Center Tax Exemption, With Conditions

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits