My personal journey with Peace Coffee began out of a simple love for coffee, but it quickly evolved into a deeper understanding of the industry’s complexities and the importance of ethical practices. Working here has opened my eyes to how unfairly coffee farmers can be treated, and that realization has profoundly changed my relationship with coffee.

This awareness drives my commitment to sustainability and fair trade, recognizing that our choices today will have lasting effects on all life on Earth.

Working at Peace Coffee has shown me how important it is to “vote with my dollar” and support organizations creating sustainable and equitable products. Yet, when I go to the store, I see numerous confusing, misleading product labels boasting they are “green” as a marketing tactic. Their labels don’t require their business to commit to sustainable practices.

Here are a few questions to ask yourself the next time you are at the grocery store trying to buy sustainable:

1. Is it “Fair Trade” and “Organic” certified?

When you are in the grocery store aisle, check to see if the product is “certified organic and fair trade.” To be organically certified, coffee farmers must use natural, chemical-free processes to grow and harvest coffee beans while adhering to defined standards and practices. Similarly, fair trade coffee farms must be democratically organized and abide by international guidelines to ensure the premiums earned through this certification are distributed fairly and used to benefit whatever the farmers have collectively voted on.

Peace Coffee was founded by the Institute for Agriculture and Trade Policy (IATP) in 1996 with the primary goal of creating a proof-of-concept that it was possible to import and sell organic, fair-trade coffee in a way that benefited small-scale farmers rather than exploiting them—and it worked! Almost 30 years later, we’re still paying fair trade and organic premiums to our producer partners and ensuring they earn fair pay for their work. When browsing, watch for 100% organic and fair trade; rigorous standards are required to achieve that label.

2. Is it sustainable locally?

Local climate action is critical. This is especially true for our food! Sometimes, with products like coffee, it’s hard for a product to be 100% local. It’s important to buy local food if you can, and where that isn’t possible, it’s essential to see how an organization prioritizes sustainable practices at the local distribution level. For example, our local community means a lot to us, and we show that love in a few different ways. Our roastery is centrally located in the city, allowing us to deliver 50% of our coffee locally via bike all year— something we’ve been doing since day one! From composting to offering our burlap bags for gardening projects and so much more, we take our responsibility to the environment seriously, starting in our local community. If you are considering buying a product regularly, review their website to see how that business is taking action locally. Are they doing something concrete for the community? Do their values align with yours?

3. Is it B Corporation status?

What is a B Corporation Status? It’s a very high standard to achieve, and if you see this on a product, you know the food you are eating meets rigorous standards for both environmental and social good.

Peace Coffee is a certified B Corporation, meaning standards outlined by B Labs on social and environmental impact are met throughout our supply chain. The bar continues to be raised, so we’re incentivized to improve and continue pushing ourselves. Businesses that wish to achieve certification are scored on several key areas that reflect social and environmental impact. Things like transparency in operations, the wages and job security of the employees, involvement in charity work, efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, and even the quality of the product or service are all scored based on specific metrics and standards and to be certified your business must meet a minimum score threshold. Our current score is 118.7, 18.2 points more than our first score. The core of this process is transparency, so we welcome you to read a detailed breakdown of our score on the B Labs website.

These three questions will hopefully help you buy products that are truly sustainable and equitable. Coffee is a product that can be hard to fully know if the product you are buying is actually “green.” That’s why I love Peace Coffee. From our organic-only offerings since the beginning and our centrally located roastery making for convenient van and bike deliveries, to our reinvestments in our farming communities, meeting the rigorous standard set by B Lab, and so much more, we really mean it when we say we’re “In It For Good.” At Peace Coffee, we strive to lead by example in sustainable and ethical business practices. Join us on our journey and check out our website to learn more about our commitment to sustainability. Remember that protecting Earth is a team effort—we’re all in this together!

Amir Adan is Peace Coffee’s Social Media Specialist. As a Zoomer raised on the internet, he enjoys making fun content at work and for his personal social media pages. When he’s not at work, you can find him zipping around the Twin Cities on his e-bike, playing with his kitten, or cheering on our local pro-soccer team, Minnesota United FC.

The post Three questions to ask yourself buying groceries appeared first on Climate Generation.

Climate Change

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

Drought and heatwaves occurring together – known as “compound” events – have “surged” across the world since the early 2000s, a new study shows.

Compound drought and heat events (CDHEs) can have devastating effects, creating the ideal conditions for intense wildfires, such as Australia’s “Black Summer” of 2019-20 where bushfires burned 24m hectares and killed 33 people.

The research, published in Science Advances, finds that the increase in CDHEs is predominantly being driven by events that start with a heatwave.

The global area affected by such “heatwave-led” compound events has more than doubled between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, the study says.

The rapid increase in these events over the last 23 years cannot be explained solely by global warming, the authors note.

Since the late 1990s, feedbacks between the land and the atmosphere have become stronger, making heatwaves more likely to trigger drought conditions, they explain.

One of the study authors tells Carbon Brief that societies must pay greater attention to compound events, which can “cause severe impacts on ecosystems, agriculture and society”.

Compound events

CDHEs are extreme weather events where drought and heatwave conditions occur simultaneously – or shortly after each other – in the same region.

These events are often triggered by large-scale weather patterns, such as “blocking” highs, which can produce “prolonged” hot and dry conditions, according to the study.

Prof Sang-Wook Yeh is one of the study authors and a professor at the Ewha Womans University in South Korea. He tells Carbon Brief:

“When heatwaves and droughts occur together, the two hazards reinforce each other through land-atmosphere interactions. This amplifies surface heating and soil moisture deficits, making compound events more intense and damaging than single hazards.”

CDHEs can begin with either a heatwave or a drought.

The sequence of these extremes is important, the study says, as they have different drivers and impacts.

For example, in a CDHE where the heatwave was the precursor, increased direct sunshine causes more moisture loss from soils and plants, leading to a drought.

Conversely, in an event where the drought was the precursor, the lack of soil moisture means that less of the sun’s energy goes into evaporation and more goes into warming the Earth’s surface. This produces favourable conditions for heatwaves.

The study shows that the majority of CDHEs globally start out as a drought.

In recent years, there has been increasing focus on these events due to the devastating impact they have on agriculture, ecosystems and public health.

In Russia in the summer of 2010, a compound drought-heatwave event – and the associated wildfires – caused the death of nearly 55,000 people, the study notes.

The record-breaking Pacific north-west “heat dome” in 2021 triggered extreme drought conditions that caused “significant declines” in wheat yields, as well as in barley, canola and fruit production in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, says the study.

Increasing events

To assess how CDHEs are changing, the researchers use daily reanalysis data to identify droughts and heatwaves events. (Reanalysis data combines past observations with climate models to create a historical climate record.) Then, using an algorithm, they analyse how these events overlap in both time and space.

The study covers the period from 1980 to 2023 and the world’s land surface, excluding polar regions where CDHEs are rare.

The research finds that the area of land affected by CDHEs has “increased substantially” since the early 2000s.

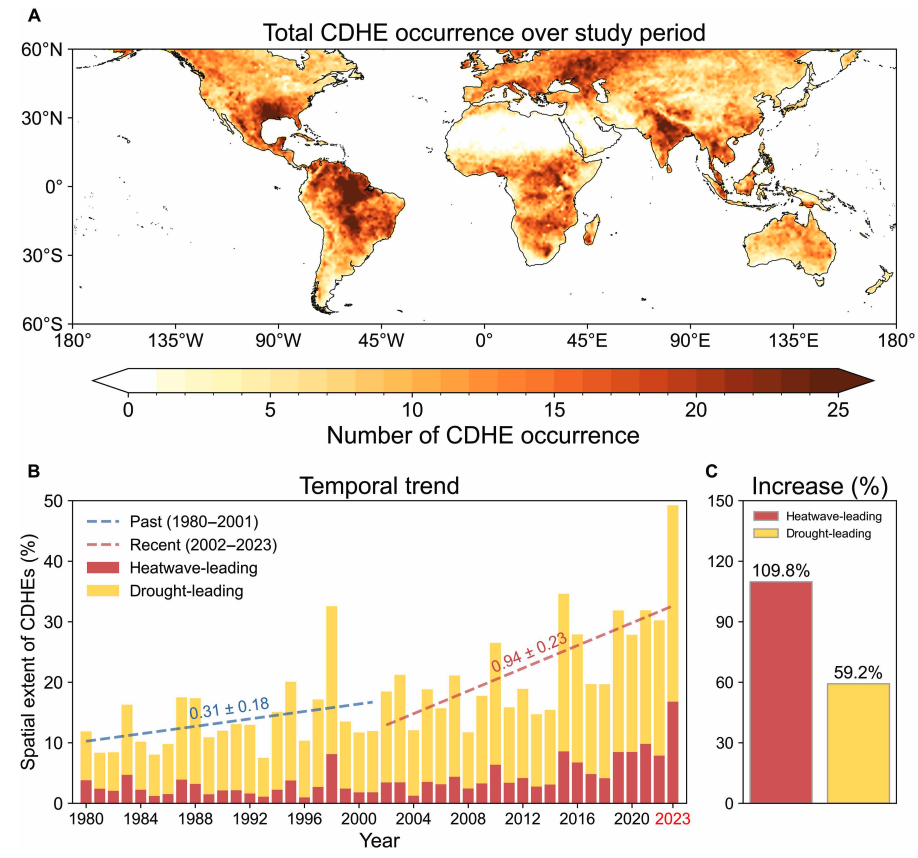

Heatwave-led events have been the main contributor to this increase, the study says, with their spatial extent rising 110% between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, compared to a 59% increase for drought-led events.

The map below shows the global distribution of CDHEs over 1980-2023. The charts show the percentage of the land surface affected by a heatwave-led CDHE (red) or a drought-led CDHE (yellow) in a given year (left) and relative increase in each CDHE type (right).

The study finds that CDHEs have occurred most frequently in northern South America, the southern US, eastern Europe, central Africa and south Asia.

Threshold passed

The authors explain that the increase in heatwave-led CDHEs is related to rising global temperatures, but that this does not tell the whole story.

In the earlier 22-year period of 1980-2001, the study finds that the spatial extent of heatwave-led CDHEs rises by 1.6% per 1C of global temperature rise. For the more-recent period of 2022-23, this increases “nearly eightfold” to 13.1%.

The change suggests that the rapid increase in the heatwave-led CDHEs occurred after the global average temperature “surpasse[d] a certain temperature threshold”, the paper says.

This threshold is an absolute global average temperature of 14.3C, the authors estimate (based on an 11-year average), which the world passed around the year 2000.

Investigating the recent surge in heatwave-leading CDHEs further, the researchers find a “regime shift” in land-atmosphere dynamics “toward a persistently intensified state after the late 1990s”.

In other words, the way that drier soils drive higher surface temperatures, and vice versa, is becoming stronger, resulting in more heatwave-led compound events.

Daily data

The research has some advantages over other previous studies, Yeh says. For instance, the new work uses daily estimations of CDHEs, compared to monthly data used in past research. This is “important for capturing the detailed occurrence” of these events, says Yeh.

He adds that another advantage of their study is that it distinguishes the sequence of droughts and heatwaves, which allows them to “better understand the differences” in the characteristics of CDHEs.

Dr Meryem Tanarhte is a climate scientist at the University Hassan II in Morocco, and Dr Ruth Cerezo Mota is a climatologist and a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Both scientists, who were not involved in the study, agree that the daily estimations give a clearer picture of how CDHEs are changing.

Cerezo-Mota adds that another major contribution of the study is its global focus. She tells Carbon Brief that in some regions, such as Mexico and Africa, there is a lack of studies on CDHEs:

“Not because the events do not occur, but perhaps because [these regions] do not have all the data or the expertise to do so.”

However, she notes that the reanalysis data used by the study does have limitations with how it represents rainfall in some parts of the world.

Compound impacts

The study notes that if CDHEs continue to intensify – particularly events where heatwaves are the precursors – they could drive declining crop productivity, increased wildfire frequency and severe public health crises.

These impacts could be “much more rapid and severe as global warming continues”, Yeh tells Carbon Brief.

Tanarhte notes that these events can be forecasted up to 10 days ahead in many regions. Furthermore, she says, the strongest impacts can be prevented “through preparedness and adaptation”, including through “water management for agriculture, heatwave mitigation measures and wildfire mitigation”.

The study recommends reassessing current risk management strategies for these compound events. It also suggests incorporating the sequences of drought and heatwaves into compound event analysis frameworks “to enhance climate risk management”.

Cerezo-Mota says that it is clear that the world needs to be prepared for the increased occurrence of these events. She tells Carbon Brief:

“These [risk assessments and strategies] need to be carried out at the local level to understand the complexities of each region.”

The post Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

Climate Change

DeBriefed 6 March 2026: Iran energy crisis | China climate plan | Bristol’s ‘pioneering’ wind turbine

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Energy crisis

ENERGY SPIKE: US-Israeli attacks on Iran and subsequent counterattacks across the Middle East have sent energy prices “soaring”, according to Reuters. The newswire reported that the region “accounts for just under a third of global oil production and almost a fifth of gas”. The Guardian noted that shipping traffic through the strait of Hormuz, which normally ferries 20% of the world’s oil, “all but ground to a halt”. The Financial Times reported that attacks by Iran on Middle East energy facilities – notably in Qatar – triggered the “biggest rise in gas prices since Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine”.

‘RISK’ AND ‘BENEFITS’: Bloomberg reported on increases in diesel prices in Europe and the US, speculating that rising fuel costs could be “a risk for president Donald Trump”. US gas producers are “poised to benefit from the big disruption in global supply”, according to CNBC. Indian government sources told the Economic Times that Russia is prepared to “fulfil India’s energy demands”. China Daily quoted experts who said “China’s energy security remains fundamentally unshaken”, thanks to “emergency stockpiles and a wide array of import channels”.

‘ESSENTIAL’ RENEWABLES: Energy analysts said governments should cut their fossil-fuel reliance by investing in renewables, “rather than just seeking non-Gulf oil and gas suppliers”, reported Climate Home News. This message was echoed by UK business secretary Peter Kyle, who said “doubling down on renewables” was “essential” amid “regional instability”, according to the Daily Telegraph.

China’s climate plan

PEAK COAL?: China has set out its next “five-year plan” at the annual “two sessions” meeting of the National People’s Congress, including its climate strategy out to 2030, according to the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post. The plan called for China to cut its carbon emissions per unit of gross domestic product (GDP) by 17% from 2026 to 2030, which “may allow for continued increase in emissions given the rate of GDP growth”, reported Reuters. The newswire added that the plan also had targets to reach peak coal in the next five years and replace 30m tonnes per year of coal with renewables.

ACTIVE YET PRUDENT: Bloomberg described the new plan as “cautious”, stating that it “frustrat[es] hopes for tighter policy that would drive the nation to peak carbon emissions well before president Xi Jinping’s 2030 deadline”. Carbon Brief has just published an in-depth analysis of the plan. China Daily reported that the strategy “highlights measures to promote the climate targets of peaking carbon dioxide emissions before 2030”, which China said it would work towards “actively yet prudently”.

Around the world

- EU RULES: The European Commission has proposed new “made in Europe” rules to support domestic low-carbon industries, “against fierce competition from China”, reported Agence France-Presse. Carbon Brief examined what it means for climate efforts.

- RECORD HEAT: The US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration has said there is a 50-60% chance that the El Niño weather pattern could return this year, amplifying the effect of global warming and potentially driving temperatures to “record highs”, according to Euronews.

- FLAGSHIP FUND: The African Development Bank’s “flagship clean energy fund” plans to more than double its financing to $2.5bn for African renewables over the next two years, reported the Associated Press.

- NO WITHDRAWAL: Vanuatu has defied US efforts to force the Pacific-island nation to drop a UN draft resolution calling on the world to implement a landmark International Court of Justice (ICJ) ruling on climate, according to the Guardian.

98

The number of nations that submitted their national reports on tackling nature loss to the UN on time – just half of the 196 countries that are part of the UN biodiversity treaty – according to analysis by Carbon Brief.

Latest climate research

- Sea levels are already “much higher than assumed” in most assessments of the threat posed by sea-level rise, due to “inadequate” modelling assumptions | Nature

- Accelerating human-caused global warming could see the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C limit crossed before 2030 | Geophysical Research Letters covered by Carbon Brief

- Future “super El Niño events” could “significantly lower” solar power generation due to a reduction in solar irradiance in key regions, such as California and east China | Communications Earth & Environment

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

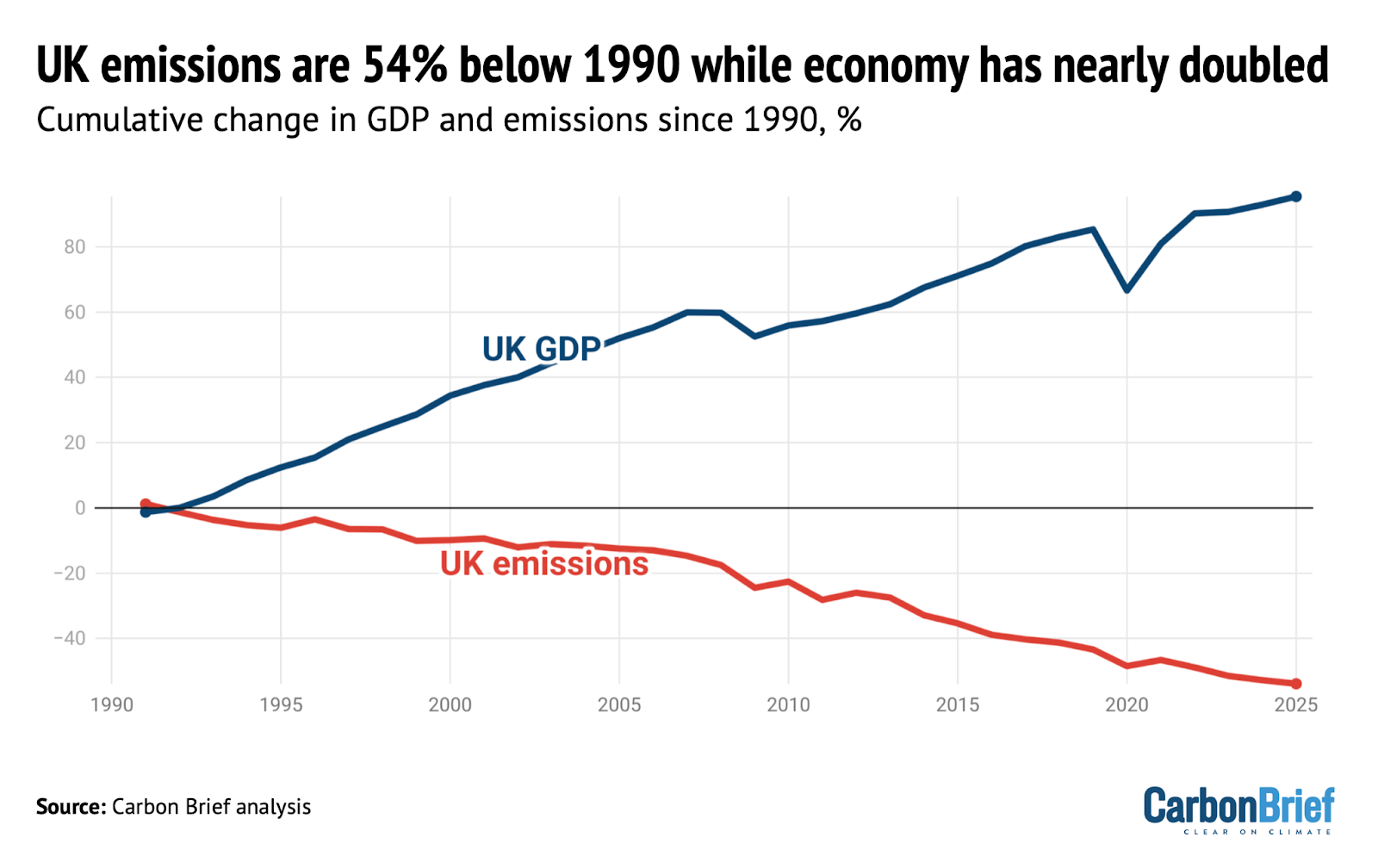

UK greenhouse gas emissions in 2025 fell to 54% below 1990 levels, the baseline year for its legally binding climate goals, according to new Carbon Brief analysis. Over the same period, data from the World Bank shows that the UK’s economy has expanded by 95%, meaning that emissions have been decoupling from growth.

Spotlight

Bristol’s ‘pioneering’ community wind turbine

Following the recent launch of the UK government’s local power plan, Carbon Brief visits one of the country’s community-energy success stories.

The Lawrence Weston housing estate is set apart from the main city of Bristol, wedged between the tree-lined grounds of a stately home and a sprawl of warehouses and waste incinerators. It is one of the most deprived areas in the city.

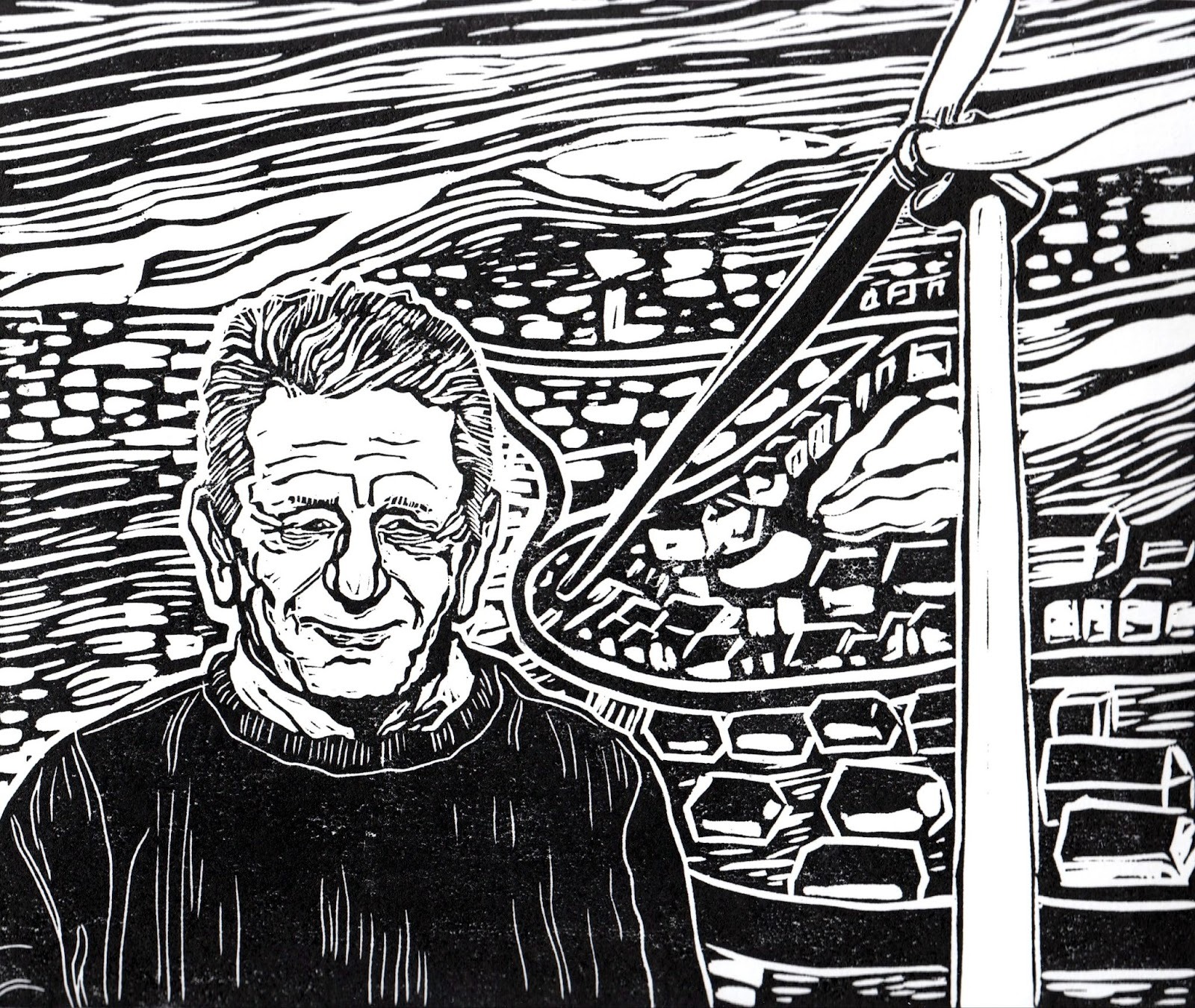

Yet, just across the M5 motorway stands a structure that has brought the spoils of the energy transition directly to this historically forgotten estate – a 4.2 megawatt (MW) wind turbine.

The turbine is owned by local charity Ambition Lawrence Weston and all the profits from its electricity sales – around £100,000 a year – go to the community. In the UK’s local power plan, it was singled out by energy secretary Ed Miliband as a “pioneering” project.

‘Sustainable income’

On a recent visit to the estate by Carbon Brief, Ambition Lawrence Weston’s development manager, Mark Pepper, rattled off the story behind the wind turbine.

In 2012, Pepper and his team were approached by the Bristol Energy Cooperative with a chance to get a slice of the income from a new solar farm. They jumped at the opportunity.

“Austerity measures were kicking in at the time,” Pepper told Carbon Brief. “We needed to generate an income. Our own, sustainable income.”

With the solar farm proving to be a success, the team started to explore other opportunities. This began a decade-long process that saw them navigate the Conservative government’s “ban” on onshore wind, raise £5.5m in funding and, ultimately, erect the turbine in 2023.

Today, the turbine generates electricity equivalent to Lawrence Weston’s 3,000 households and will save 87,600 tonnes of carbon dioxide (CO2) over its lifetime.

‘Climate by stealth’

Ambition Lawrence Weston’s hub is at the heart of the estate and the list of activities on offer is seemingly endless: birthday parties, kickboxing, a library, woodworking, help with employment and even a pop-up veterinary clinic. All supported, Pepper said, with the help of a steady income from community-owned energy.

The centre itself is kitted out with solar panels, heat pumps and electric-vehicle charging points, making it a living advertisement for the net-zero transition. Pepper noted that the organisation has also helped people with energy costs amid surging global gas prices.

Gesturing to the England flags dangling limply on lamp posts visible from the kitchen window, he said:

“There’s a bit of resentment around immigration and scarcity of materials and provision, so we’re trying to do our bit around community cohesion.”

This includes supper clubs and an interfaith grand iftar during the Muslim holy month of Ramadan.

Anti-immigration sentiment in the UK has often gone hand-in-hand with opposition to climate action. Right-wing politicians and media outlets promote the idea that net-zero policies will cost people a lot of money – and these ideas have cut through with the public.

Pepper told Carbon Brief he is sympathetic to people’s worries about costs and stressed that community energy is the perfect way to win people over:

“I think the only way you can change that is if, instead of being passive consumers…communities are like us and they’re generating an income to offset that.”

From the outset, Pepper stressed that “we weren’t that concerned about climate because we had other, bigger pressures”, adding:

“But, in time, we’ve delivered climate by stealth.”

Watch, read, listen

OIL WATCH: The Guardian has published a “visual guide” with charts and videos showing how the “escalating Iran conflict is driving up oil and gas prices”.

MURDER IN HONDURAS: Ten years on from the murder of Indigenous environmental justice advocate Berta Cáceres, Drilled asked why Honduras is still so dangerous for environmental activists.

TALKING WEATHER: A new film, narrated by actor Michael Sheen and titled You Told Us To Talk About the Weather, aimed to promote conversation about climate change with a blend of “poetry, folk horror and climate storytelling”.

Coming up

- 8 March: Colombia parliamentary election

- 9-19 March: 31st Annual Session of the International Seabed Authority, Kingston, Jamaica

- 11 March: UN Environment Programme state of finance for nature 2026 report launch

Pick of the jobs

- London School of Economics and Political Science, fellow in the social science of sustainability | Salary: £43,277-£51,714. Location: London

- NORCAP, innovative climate finance expert | Salary: Unknown. Location: Kyiv, Ukraine

- WBHM, environmental reporter | Salary: $50,050-$81,330. Location: Birmingham, Alabama, US

- Climate Cabinet, data engineer | Salary: hourly rate of $60-$120 per hour. Location: Remote anywhere in the US

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 6 March 2026: Iran energy crisis | China climate plan | Bristol’s ‘pioneering’ wind turbine appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Deep divisions persist as plastics treaty talks restart at informal meeting

Officials from about 20 countries met informally in Japan this week in a bid to bridge major differences in talks on a global treaty to curb plastic pollution, eight months after the last round of negotiations collapsed without agreement.

A participant told Climate Home News the closed-door meeting, hosted by Japan’s Environment Ministry, had been helpful to test ideas and restart conversations before formal talks resume, but said progress remained “challenging”, with national stances largely unchanged.

The meeting brought together countries pushing for efforts to rein in soaring plastic production, including European and Latin American nations, with major fossil fuel producers such as the United States, Saudi Arabia, Russia and Kuwait, which say the treaty should focus only on managing waste.

US hits out at EU and Pacific islands

In a sign of the persistent divisions, a spokesperson for the US State Department told Climate Home News after the meeting that Washington opposes “global plastic bans driven by the EU and Pacific Islands that would harm our economy and raise consumer prices”.

The EU and other members of the so-called High Ambition Coalition have called for the phase-out of certain plastic products that pose significant risks to human health and the environment, but have not advocated for any wide-ranging plastic ban.

“The EU is committed to securing a treaty with global measures across the full lifecycle of plastics, from production and consumption to waste management and end-of-life treatment,” a European Commission spokesperson told Climate Home News. “A global treaty can unlock economic opportunities, next to its environmental and health benefits,” the spokesperson added.

Dennis Clare, a negotiator for the Pacific island nation of Micronesia, told Climate Home News that the world produces too much plastic, driving the plastic and climate pollution that all countries are struggling so hard to reduce.

He said he hoped countries could agree on enough actions in the treaty to make some meaningful progress towards ending plastic pollution, but he added that there should be flexibility to adjust course along the way.

Rescuing talks from turmoil

Plastic production is set to triple by 2060 without intervention, according to the UN. As nearly all plastic is made from planet-heating oil, gas and coal, the sector’s trajectory will have a significant impact on global efforts to reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The informal talks this week were seen as an attempt to facilitate discussions between some of the key nations before formal negotiations guided by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) resume.

The process, which began in February 2022, was thrown into turmoil in the second half of last year. In August, nations left what was meant to be the last round of talks in Geneva with no agreement or a clear way forward after a chaotic night of negotiations. Two months later, the chair of the talks, Ecuadorean diplomat Luis Vayas Valdivieso, stepped down, citing personal and professional reasons.

Believing that countries can still deliver “a treaty for the ages”, the UNEP has been working to steer the process back on track. Veteran Chilean ambassador Julio Cordano was elected as the new chair during a one-day session in early February. In a letter to diplomats, Cordano acknowledged the task was “hard and complex”, but said establishing a global treaty was “not only achievable, but also urgently needed”.

Call for inclusivity

Andrés Del Castillo, a senior attorney at the Center for International Environmental Law (CIEL), said it was important to keep the process transparent and inclusive.

While Japan’s efforts to use its diplomatic leverage to address thorny issues are commendable, only a handful of countries – including “some of the biggest blockers” – attended the informal meeting, he said, while others championing stronger action were left out.

Explainer: Will AI data centres make or break the energy transition?

Following this week’s restricted gathering in Tokyo, all countries are set to exchange views on the way forward during an online meeting hosted by Cordano on March 12. It remains unclear when governments will reconvene for a formal negotiating session, but diplomats told Climate Home it is unlikely to take place in the first half of 2026.

A participant at the Tokyo meeting said countries must produce a significant shift in positions in the coming months to make reconvening formal negotiations worthwhile.

The post Deep divisions persist as plastics treaty talks restart at informal meeting appeared first on Climate Home News.

Deep divisions persist as plastics treaty talks restart at informal meeting

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits