Besides the dust that cloaks pathways, windowsills and gardens, the towering grey heaps of discarded rock are another unwelcome reminder of the platinum mine next door to the South African township of Chaneng.

In and around the city of Rustenburg, the low-grade platinum ore that has made South Africa the world’s top producer of the silvery metal creates massive waste piled in large rocky heaps known as tailings. For every tonne of metal extracted, hundreds of tonnes of waste rock is left behind in huge piles.

The transition to cleaner energy system is expected to push up global demand for platinum group metals (PGM) – which include palladium and other precious metals, as well as platinum. They are used in hydrogen-related technologies such as fuel cells and electrolysers that split water molecules as well as in hybrid cars that need catalytic converters to curb pollution.

To secure supplies, mining companies are starting to make use of what was once considered waste.

Efforts to green lithium extraction face scrutiny over water use

Reprocessing mine tailings using new technology can be a more sustainable form of producing minerals and metals needed for the energy transition because it is expected to reduce the size of existing waste heaps and boost output without the need to open new mines, which can cause more environmental destruction and community displacement.

“Tailings reprocessing offers genuine benefits, reducing pressure for new mining [and] addressing existing environmental liabilities,” said Mathikoza Dube, an expert on critical minerals based in Rustenburg.

“It offers the world a pathway to secure supplies of energy transition minerals while remediating waste that’s contaminated communities for generations,” Dube added, cautioning it is not a “magic solution” and should be approached in a way that ensures local communities benefit.

In Chaneng, where the tailings dumps loom over backyards, residents are wary.

“Same theft in new clothes”

They fear the plan to reprocess mining tailings at the neighbouring mine – operated by South African platinum miner Sibanye-Stillwater – is being dressed up as sustainable when in reality it will mean more contamination, blasting, dust and no end to their community’s problems.

Despite decades of mining, unemployment in the area remains high, many people say they never received compensation for the loss of their agricultural land and most households still lack access to basic sanitation infrastructure.

Water testing carried out by SRK Consulting in 2009 found elevated nitrate levels exceeding World Health Organization guidelines in community boreholes, and health practitioners document dramatic increases in respiratory diseases.

“Now they want to dig up the waste piles and call it progress? Show us the ownership papers. Show us the rehabilitation plan. Otherwise, it’s the same theft in new clothes,” said Johannes Kgomo, a community leader.

South Africa’s mining legislation requires that 26% of mining assets are held by historically disadvantaged people including Black South Africans, and Chaneng residents are demanding a stake of 15% to 30% in any tailings operation on their land, allowing them to have a say in how the business is run.

They say that should be granted to them as compensation for the health and environmental problems they have endured as a result of the mine.

The community is also demanding comprehensive water testing and treatment, adequately resourced clinics with respiratory specialists, compensation for destroyed agricultural land, infrastructure repair and long-term health monitoring.

“We are not asking for handouts,” said Gideon Chitanga of the National Union of Mineworkers, which often takes the side of local communities in disputes with companies.

“These people have already paid with their health, their water, their land. That contamination, that suffering – that is their investment. Now they want returns and decision-making power,” Chitanga added.

A spokesperson for Sibanye-Stillwater declined to comment.

A mining industry source, who asked not to be identified, said conversations with community members were ongoing.

“Nobody disputes these communities have suffered. The question is how to structure ownership in a way that’s legally sound, financially viable, and genuinely empowering,” the source said.

New technology boosts metal recovery in waste

New reprocessing technology has made it economically viable to extract platinum group metals from tailings, and several operations are already underway in South Africa’s platinum mining belt, around the city of Rustenburg.

Sibanye-Stillwater already operates multiple retreatment facilities, processing thousands of tonnes of waste ore monthly.

Another South African miner Tharisa processes chromite from PGM tailings commercially. Chromite is used to obtain chromium, a metal used in the manufacture of wind turbines and some energy storage batteries.

“Historical tailings facilities contain economically viable concentrations that were unrecoverable with older technology,” said Leo Vonopartis from the University of the Witwatersrand’s BUGEMET research programme, which studies the geology of South Africa’s Bushveld Complex mining belt.

Tailings in the area around Rustenburg can contain up to 2.5 grammes per tonne of combined platinum, palladium and rhodium – along with chromite. Vanadium, cobalt and rare earth elements have also been found.

At current prices, which have rallied this year, it is worth extracting the rare metals, despite the challenges.

Breaking with the cycle of extraction and injustice

“The technology exists. The economics work. The question is whether we can structure these projects to genuinely benefit the people who have paid mining’s costs,” a spokesperson for one mining company said, asking not to be named.

Without that, local expert Dube said, the reprocessing of tailings is scarcely better than other forms of mining.

“Reprocessing tailings does not erase the damage that created them. If it is structured as extraction by another name – where companies profit and communities remain marginalised – we have just found a new way to perpetuate old injustices.”

Australia’s COP31 Co-President vows to fight alongside Pacific for a fossil fuel transition

Gesturing toward the tailings dam visible from her yard, Noxolo Mthembu recalls the days when her vegetable patch used to feed the family.

“We used to grow spinach, tomatoes, pumpkins,” she told Climate Home News. “Now nothing grows. The dust kills everything. My children have asthma. My husband died of lung disease at 54.”

Like many of her neighbours, she says any new cycle of mining activity – this time in the name of the clean energy transition – must not repeat the past.

“Show me the ownership papers with our names. Show me the water treatment plant. Show me the clinic with enough staff. Then I will believe this time is different.”

The post South Africa’s platinum mine dumps get a second look as clean energy lifts demand appeared first on Climate Home News.

South Africa’s platinum mine dumps get a second look as clean energy lifts demand

Climate Change

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of America’s Broken Health Care System

American farmers are drowning in health insurance costs, while their German counterparts never worry about medical bills. The difference may help determine which country’s small farms are better prepared for a changing climate.

Samantha Kemnah looked out the foggy window of her home in New Berlin, New York, at the 150-acre dairy farm she and her husband, Chris, bought last year. This winter, an unprecedented cold front brought snowstorms and ice to the region.

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of the Broken U.S. Health Care System

Climate Change

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Two Utah Congress members have introduced a resolution that could end protections for Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Conservation groups worry similar maneuvers on other federal lands will follow.

Lawmakers from Utah have commandeered an obscure law to unravel protections for the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, potentially delivering on a Trump administration goal of undoing protections for public conservation lands across the country.

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Climate Change

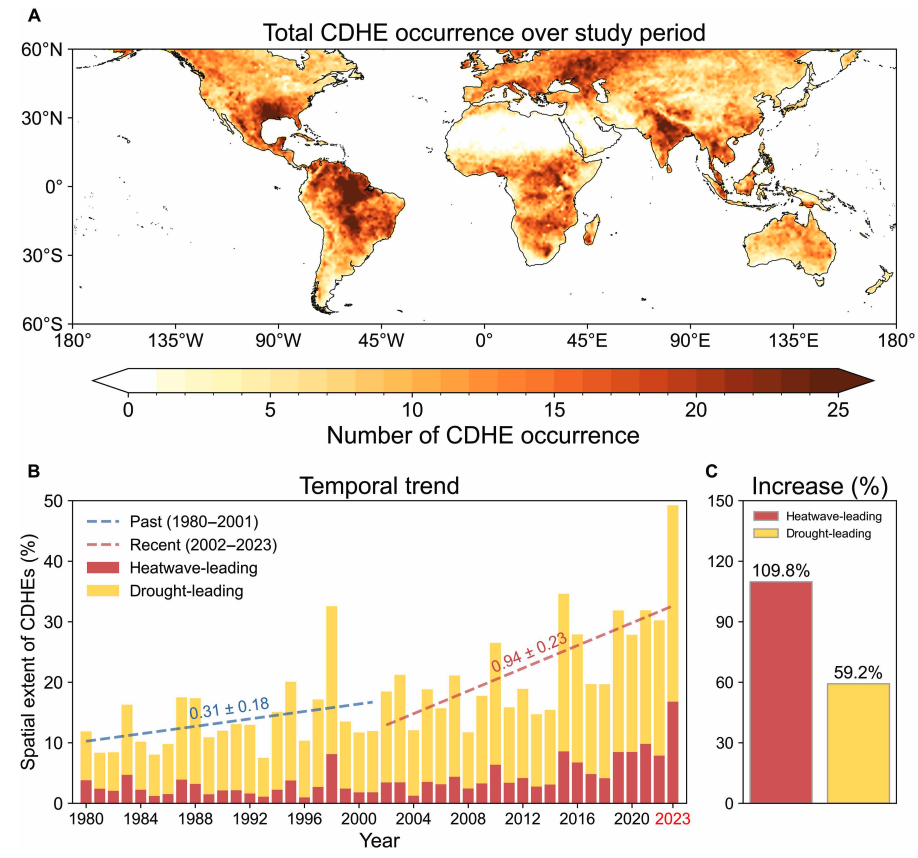

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

Drought and heatwaves occurring together – known as “compound” events – have “surged” across the world since the early 2000s, a new study shows.

Compound drought and heat events (CDHEs) can have devastating effects, creating the ideal conditions for intense wildfires, such as Australia’s “Black Summer” of 2019-20 where bushfires burned 24m hectares and killed 33 people.

The research, published in Science Advances, finds that the increase in CDHEs is predominantly being driven by events that start with a heatwave.

The global area affected by such “heatwave-led” compound events has more than doubled between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, the study says.

The rapid increase in these events over the last 23 years cannot be explained solely by global warming, the authors note.

Since the late 1990s, feedbacks between the land and the atmosphere have become stronger, making heatwaves more likely to trigger drought conditions, they explain.

One of the study authors tells Carbon Brief that societies must pay greater attention to compound events, which can “cause severe impacts on ecosystems, agriculture and society”.

Compound events

CDHEs are extreme weather events where drought and heatwave conditions occur simultaneously – or shortly after each other – in the same region.

These events are often triggered by large-scale weather patterns, such as “blocking” highs, which can produce “prolonged” hot and dry conditions, according to the study.

Prof Sang-Wook Yeh is one of the study authors and a professor at the Ewha Womans University in South Korea. He tells Carbon Brief:

“When heatwaves and droughts occur together, the two hazards reinforce each other through land-atmosphere interactions. This amplifies surface heating and soil moisture deficits, making compound events more intense and damaging than single hazards.”

CDHEs can begin with either a heatwave or a drought.

The sequence of these extremes is important, the study says, as they have different drivers and impacts.

For example, in a CDHE where the heatwave was the precursor, increased direct sunshine causes more moisture loss from soils and plants, leading to a drought.

Conversely, in an event where the drought was the precursor, the lack of soil moisture means that less of the sun’s energy goes into evaporation and more goes into warming the Earth’s surface. This produces favourable conditions for heatwaves.

The study shows that the majority of CDHEs globally start out as a drought.

In recent years, there has been increasing focus on these events due to the devastating impact they have on agriculture, ecosystems and public health.

In Russia in the summer of 2010, a compound drought-heatwave event – and the associated wildfires – caused the death of nearly 55,000 people, the study notes.

The record-breaking Pacific north-west “heat dome” in 2021 triggered extreme drought conditions that caused “significant declines” in wheat yields, as well as in barley, canola and fruit production in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, says the study.

Increasing events

To assess how CDHEs are changing, the researchers use daily reanalysis data to identify droughts and heatwaves events. (Reanalysis data combines past observations with climate models to create a historical climate record.) Then, using an algorithm, they analyse how these events overlap in both time and space.

The study covers the period from 1980 to 2023 and the world’s land surface, excluding polar regions where CDHEs are rare.

The research finds that the area of land affected by CDHEs has “increased substantially” since the early 2000s.

Heatwave-led events have been the main contributor to this increase, the study says, with their spatial extent rising 110% between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, compared to a 59% increase for drought-led events.

The map below shows the global distribution of CDHEs over 1980-2023. The charts show the percentage of the land surface affected by a heatwave-led CDHE (red) or a drought-led CDHE (yellow) in a given year (left) and relative increase in each CDHE type (right).

The study finds that CDHEs have occurred most frequently in northern South America, the southern US, eastern Europe, central Africa and south Asia.

Threshold passed

The authors explain that the increase in heatwave-led CDHEs is related to rising global temperatures, but that this does not tell the whole story.

In the earlier 22-year period of 1980-2001, the study finds that the spatial extent of heatwave-led CDHEs rises by 1.6% per 1C of global temperature rise. For the more-recent period of 2022-23, this increases “nearly eightfold” to 13.1%.

The change suggests that the rapid increase in the heatwave-led CDHEs occurred after the global average temperature “surpasse[d] a certain temperature threshold”, the paper says.

This threshold is an absolute global average temperature of 14.3C, the authors estimate (based on an 11-year average), which the world passed around the year 2000.

Investigating the recent surge in heatwave-leading CDHEs further, the researchers find a “regime shift” in land-atmosphere dynamics “toward a persistently intensified state after the late 1990s”.

In other words, the way that drier soils drive higher surface temperatures, and vice versa, is becoming stronger, resulting in more heatwave-led compound events.

Daily data

The research has some advantages over other previous studies, Yeh says. For instance, the new work uses daily estimations of CDHEs, compared to monthly data used in past research. This is “important for capturing the detailed occurrence” of these events, says Yeh.

He adds that another advantage of their study is that it distinguishes the sequence of droughts and heatwaves, which allows them to “better understand the differences” in the characteristics of CDHEs.

Dr Meryem Tanarhte is a climate scientist at the University Hassan II in Morocco, and Dr Ruth Cerezo Mota is a climatologist and a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Both scientists, who were not involved in the study, agree that the daily estimations give a clearer picture of how CDHEs are changing.

Cerezo-Mota adds that another major contribution of the study is its global focus. She tells Carbon Brief that in some regions, such as Mexico and Africa, there is a lack of studies on CDHEs:

“Not because the events do not occur, but perhaps because [these regions] do not have all the data or the expertise to do so.”

However, she notes that the reanalysis data used by the study does have limitations with how it represents rainfall in some parts of the world.

Compound impacts

The study notes that if CDHEs continue to intensify – particularly events where heatwaves are the precursors – they could drive declining crop productivity, increased wildfire frequency and severe public health crises.

These impacts could be “much more rapid and severe as global warming continues”, Yeh tells Carbon Brief.

Tanarhte notes that these events can be forecasted up to 10 days ahead in many regions. Furthermore, she says, the strongest impacts can be prevented “through preparedness and adaptation”, including through “water management for agriculture, heatwave mitigation measures and wildfire mitigation”.

The study recommends reassessing current risk management strategies for these compound events. It also suggests incorporating the sequences of drought and heatwaves into compound event analysis frameworks “to enhance climate risk management”.

Cerezo-Mota says that it is clear that the world needs to be prepared for the increased occurrence of these events. She tells Carbon Brief:

“These [risk assessments and strategies] need to be carried out at the local level to understand the complexities of each region.”

The post Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits