At 12.33pm on Monday 28 April, most of Spain and Portugal were plunged into chaos by a blackout.

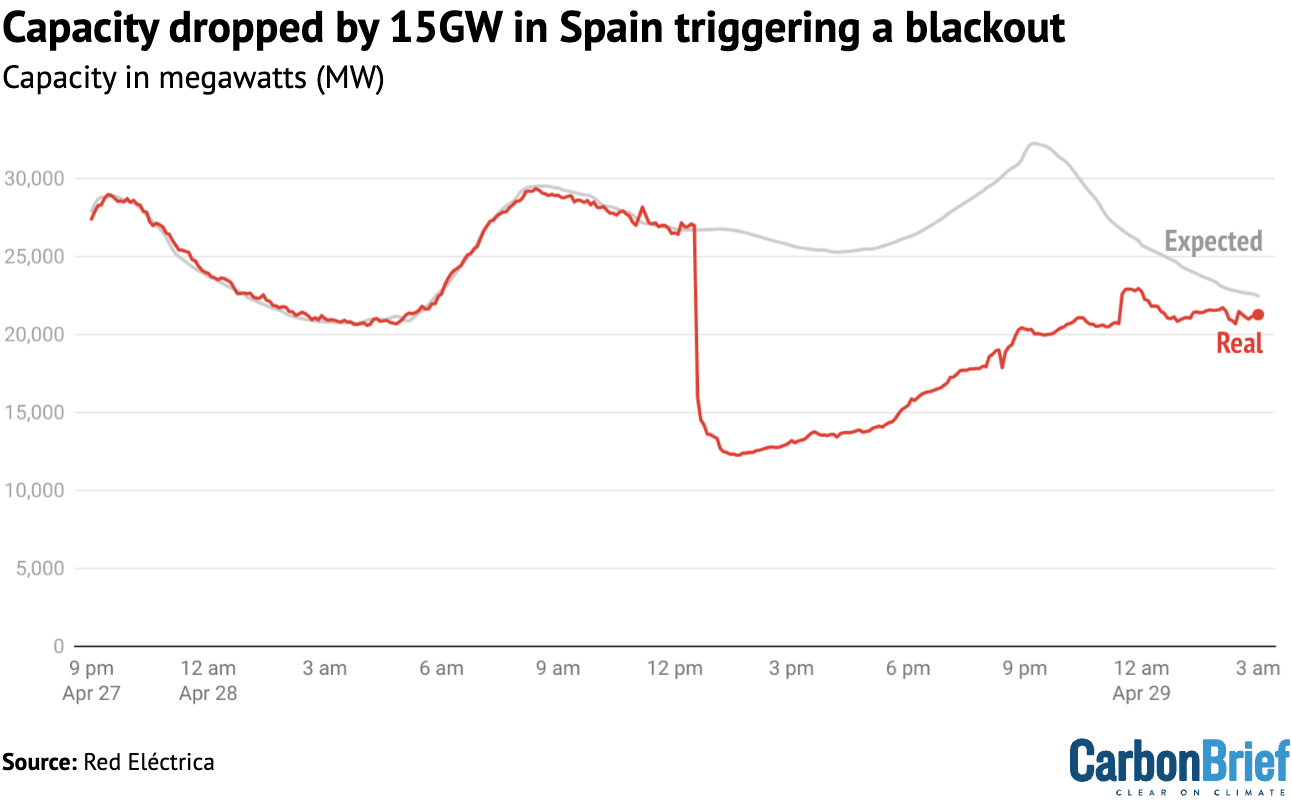

While the initial trigger remains uncertain, the nationwide blackouts took place after around 15 gigawatts (GW) of electricity generating capacity – equivalent to 60% of Spain’s power demand at the time – dropped off the system within the space of five seconds.

The blackouts left millions of people without power, with trains, traffic lights, ATMs, phone connections and internet access failing across the Iberian peninsula.

By Tuesday morning, almost all electricity supplies across Spain and Portugal had been restored, but questions about the root cause remained.

Many media outlets were quick to – despite very little available data or information – blame renewables, net-zero or the energy transition for the blackout, even if only by association, by highlighting the key role solar power plays in the region’s electricity mix.

Below, Carbon Brief examines what is known about the Spanish and Portuguese power cuts, the role of renewables and how the media has responded.

What happened and what was the impact?

The near-total power outage in the Iberian Peninsula on Monday affected millions of people.

Spain and Portugal experienced the most extensive blackouts, but Andorra also reported outages, as did the Basque region of France. According to Reuters, the blackout was the biggest in Europe’s history.

In a conference call with reporters, Spanish grid operator Red Eléctrica set out the order of events.

Shortly after 12.30pm, the grid suffered an “event” akin to loss of power generation, according to a summary of the call posted by Bloomberg’s energy and commodities columnist Javier Blas on LinkedIn. While the grid almost immediately self-stabilised and recovered, about 1.5 seconds later a second “event” hit, he wrote.

Around 3.5 seconds later, the interconnector between the Spanish region of Catalonia and south-west France was disconnected due to grid instability. Immediately after this, there was a “massive” loss of power on the system, Blas said.

This caused the power grid to “cascade down into collapse”, causing the “unexplained disappearance” of 60% of Spain’s generation, according to Politico.

It quoted Spanish prime minister Pedro Sánchez, who told a press conference late on Monday that the causes were not yet known:

“This has never happened before. And what caused it is something that the experts have not yet established – but they will.”

The figure below shows the sudden loss of 15GW of generating capacity from the Spanish grid at 12.33pm on Monday. In addition, a further 5GW disconnected from the Portuguese grid.

The Guardian noted in its coverage that “while the system weathered the first event, it could not cope with the second”.

A separate piece from the publication added that “barely a corner of the peninsula, which has a joint population of almost 60 million people, escaped the blackout”.

El País reported that “the power cut…paralysed the normal functioning of infrastructures, telecommunications, roads, train stations, airports, stores and buildings. Hospitals have not been impacted as they are using generators.”

According to Spanish newswire EFE, “hundreds of thousands of people flooded the streets, forced to walk long distances home due to paralysed metro and commuter train services, without mobile apps as telecommunications networks also faltered”.

It added that between 30,000 and 35,000 passengers had to be evacuated from stranded trains.

The New York Times reported that Portuguese banks and schools closed, while ATMs stopped working across the country and Spain. People “crammed into stores to buy food and other essentials as clerks used pen and paper to record cash-only transactions”, it added.

Spain’s interior ministry declared a national emergency, according to Reuters, deploying 30,000 police to keep order.

Both Spain and Portugal convened emergency cabinet meetings, with Spain’s King Felipe VI chairing a national security council meeting on Tuesday to discuss an investigation into the power outage, Sky News reported.

By 10pm on Monday, 421 out of Spain’s 680 substations were back online, meaning that 43% of expected power demand was being met, reported the Guardian.

By Tuesday morning, more than 99% of the total electricity supply had been recovered, according to Politico, quoting Red Eléctrica.

In Portugal, power had been restored to every substation on the country’s grid by 11.30pm on Monday. In a statement released on Tuesday, Portuguese grid operator REN said the grid had been “fully stabilised”.

What caused the power cuts?

In the wake of the power cuts, politicians, industry professionals, media outlets, armchair experts and the wider public scrambled to make sense of what had just happened.

Spanish prime minister Sánchez said on the afternoon of the blackout that the government did not have “conclusive information” on its cause, adding that it “[did] not rule out any hypothesis”, Spanish newspaper Diario Sur reported.

Nevertheless, some early theories were quickly rejected by officials.

Red Eléctrica, “preliminarily ruled out that the blackout was due to a cyberattack, human error or a meteorological or atmospheric phenomenon”, El País reported the day after the event.

Politico noted that “people in the street in Spain and some local politicians” had speculated about a cyberattack.

However, it quoted Eduardo Prieto, Red Eléctrica’s head of system operation services, saying that while the conclusions were preliminary, the operator had “been able to conclude that there has not been any type of intrusion in the electrical network control systems that could have caused the incident”.

The Majorca Daily Bulletin reported that Spain’s High Court said it would open an investigation into whether the event was the result of a cyberattack.

Initial reporting by news agencies blamed the power cuts on a “rare atmospheric phenomenon”, citing the Portuguese grid operator REN, according to the Guardian. The newspaper added that REN later said this statement had been incorrectly attributed to it.

The phenomenon in question was described as an “induced atmospheric vibration”.

Prof Mehdi Seyedmahmoudian, an electrical engineer at Swinburne University of Technology in Australia, explained in the Conversation that this was “not a commonly used term”.

Nevertheless, he said the phenomenon being described was familiar, referring to “wavelike movements” in the atmosphere caused by sudden changes in temperature or pressure.

In general terms, Reuters explained that power cuts are often linked to extreme weather, but that the “weather at the time of Monday’s collapse was fair”. It added that faults at power stations, power distribution lines or substations can also trigger outages.

Another theory was that a divergence of electrical frequency from 50 cycles per second (Hz), the European standard, could have caused parts of the system to shut down in order to protect equipment, France 24 explained.

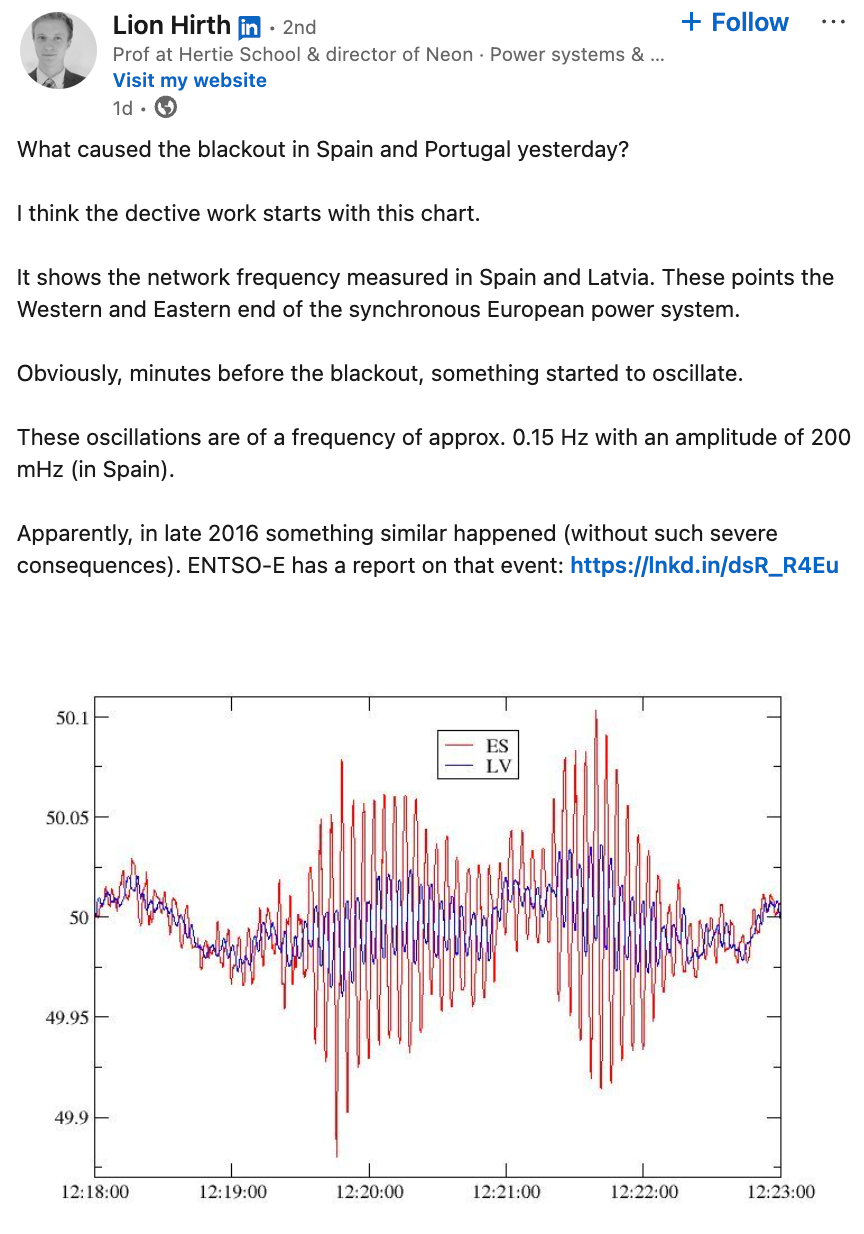

Some analysts noted that “oscillations” in grid frequency shortly before the events in Spain and Portugal could be related to the power cuts. Tobias Burke, policy manager at Energy UK, explained this theory in his Substack:

“The fact these frequency oscillations mirrored those in Latvia…at the other extreme of the Europe-spanning ENTSO-E network, might suggest complex inter-area oscillations across markets could be the culprit.”

This phenomenon can be seen in a chart shared by Prof Lion Hirth, an energy researcher at Hertie School, on LinkedIn.

With many details still unknown, much of the media speculation has focused on the role that renewable energy could have played in the blackouts. (See: Did renewable energy play a role in the cut?)

Many of the experts cited in the media emphasised the complexity of determining the cause of the outages. Eamonn Lannoye, managing director at the Electric Power Research Institute Europe, was quoted by the Associated Press stating:

“There’s a variety of things that usually happen at the same time and it’s very difficult for any event to say ‘this was the root cause’.”

Nevertheless, there are several efforts now underway to determine what the causes were.

Portugal’s prime minister, Luís Montenegro, announced on Tuesday that the government would set up an independent technical commission to investigate the blackouts, while stressing that the problem had originated in Spain, according to Euractiv.

Finally, EU energy commissioner Dan Jørgensen has indicated that the EU will open a “thorough investigation” into the reasons behind the power cuts, BBC News noted.

Did renewable energy play a role in the blackouts?

As commentators began to look into the cause of the blackout, many pointed to the high share of renewables in Spain’s electricity mix.

On 16 April, Spain’s grid had run entirely on renewable sources for a full day for the first time ever, with wind accounting for 46% of total output, solar 27%, hydroelectric 23% and solar thermal and others meeting the rest, according to PV Magazine.

Spain is targeting 81% renewable power by 2030 and 100% by 2050.

At the time of the blackout on Monday, solar accounted for 59% of the country’s electricity supplies, wind nearly 12%, nuclear 11% and gas around 5%, reported the Independent.

The initial “event” is thought to have originated in the south-western region of Extremadura, noted Politico, “which is home to the country’s most powerful nuclear power plant, some of its largest hydroelectric dams and numerous solar farms.”

On Tuesday, Red Eléctrica’s head of system operation services Eduardo Prieta said that it was “very possible that the affected generation [in the initial ‘events’] could be solar”.

This sparked further speculation about how grids that are highly reliant on variable renewables can be managed so as to ensure security of supply.

Political groups such as the far-right VOX – which has historically pushed back against climate action such as the expansion of renewables – also pointed to the blackout as evidence of “the importance of a balanced energy mix”.

However, others rejected this suggestion, with EU energy chief Dan Jørgensen telling Bloomberg that the blackout could not be pinned on a “specific source of energy”:

“As far as we know, there was nothing unusual about the sources of energy supplying electricity to the system yesterday. So the causes of the blackout cannot be reduced to a specific source of energy, for instance renewables.”

Others have sought to highlight that, while it was possible solar power was involved in the initial frequency event, this does not mean that it was ultimately the cause of the blackout.

Writing on LinkedIn, chief technology officer of Arenko, a renewable energy software company, Roger Hollies, noted:

“The initial trip may well have been a solar plant, but trips happen all the time across all asset types. Networks should be designed to withstand multiple loss of generators. 15GW is not one power station, this is the equivalent of 10 large gas or nuclear power stations or 75 solar parks.”

Others pointed to what they said was insufficient nuclear power on the grid – a notion that prime minister Sánchez rejected, according to El País.

Speaking on Tuesday, he said that those arguing the blackouts showed a need for more nuclear power were “either lying or showing ignorance”, according to the newspaper. It said he highlighted that nuclear plants were yet to fully recover from the event.

One key aspect of the transition away from electricity systems built around thermal power stations burning coal, gas or uranium is a loss of “inertia”, the Financial Times highlighted.

Thermal power plants generate electricity using large spinning turbines, which rotate at the same 50 cycles per second (Hz) speed as the electrical grid oscillates. The weight of these “large lump[s] of spinning metal” gives them “inertia”, which counteracts changes in frequency on the rest of the grid.

When faults cause a rise or fall in grid frequency, this inertia helps lower the rate of change of frequency, giving system operators more time to respond, noted Adam Bell, director of policy at Stonehaven, in a post on LinkedIn.

Solar does not include a spinning generator, and therefore, critics pointed to the lack of inertia on the grid due to the high levels of the technology as a cause of the blackout.

As Bell pointed out, this ignores the inertia provided by nuclear, hydro and solar thermal on the grid at the time of the blackout, alongside the Spanish grid operator having built “synchronous condensers” to help boost inertia and grid stability.

Bell added:

“A lack of inertia was therefore not the main driver for the blackout. Indeed, post the frequency event, no fossil generation remained online – but wind, solar and hydro did.”

While the ultimate cause of the blackouts remains to be seen, they have highlighted the need for an increased focus on grid stability, particularly as the economy is electrified.

A selection of comments from experts published in Review Energy emphasises the need for further resilience to be built into the grid as it transitions away from fossil fuels.

How has the media responded to the power cut?

As the crisis was still unfolding and its cause remained unknown, several climate-sceptic right-leaning UK publications clamoured to draw a link between the blackouts and the nations’ reliance on renewable energy.

It comes as right-leaning titles have stepped up their campaigning against climate policy over the past year.

On Tuesday, the Daily Telegraph carried a frontpage story headlined: “Net-zero blamed for blackout chaos.”

But the article contradicted its own headline by concluding: “What exactly happened remains unclear for now. And the real answer is likely to involve several factors, not just one.”

None of the experts quoted in the piece blamed “net-zero” for the incident.

The Daily Telegraph also carried an editorial seeking to argue renewable energy was the cause of the blackouts, which claimed that “over-reliance on renewables means a less resilient grid”.

The Daily Express had an editorial (not online) claiming that the blackout shows “relying on renewables is dim”.

Additionally, the Standard carried a comment by notorious climate-sceptic commentator Ross Clark breathlessly blaming the blackout on “unreliable” renewables, with a fear-monguering warning that the “same could happen in the UK”.

The Daily Mail published a comment by Rupert Darwall, a climate-sceptic author who is part of the CO2 Coalition – an organisation seeking to promote “the important contribution made by carbon dioxide to our lives” – which claimed that the blackout showed “energy security is being sacrificed at the altar of green dogma”.

Climate-sceptic libertarian publication Spiked had a piece by its deputy editor Fraser Myers titled: “Spain’s blackouts are a disaster made by net-zero.” The article claimed that “our elites’ embrace of green ideology has divorced them from reality”.

In Spanish media, Jordi Sevilla, the former president of Red Eléctrica, wrote in the financial publication Cinco Días that, while it is not known what caused the blackout, it is clear that the country’s grid “requires investments to adapt to the technical reality of the new generation mix”. He continued:

“In Spain, in the last decade, there has been a revolution in electricity generation to the point that renewable technologies ([solar] photovoltaic and wind, above all) now occupy the majority of the energy mix. This has had very positive impacts on CO2 emissions, lower electricity prices and increased national autonomy.

“But there is a technical problem: photovoltaic and wind power are not synchronous energies, whereas our transmission and distribution networks are designed to operate only with a minimum voltage in the energy they transport. Therefore, to operate with current technology, the electrical system must maintain synchronous backup power, which can be hydroelectric, gas or nuclear, to be used when photovoltaic and wind power are insufficient, either due to their intermittent nature (there may be no sun or wind) or due to the lack of synchronisation required by the generators to operate.”

For Bloomberg, opinion columnist Javier Blas said that “Spain’s blackout shouldn’t trigger a retreat from renewables”, but shows that “an upgraded grid is urgently needed for the energy transition”. He added:

“The world didn’t walk away from fossil-fuel and nuclear power stations because New York suffered a massive blackout in 1977. And it shouldn’t walk away from solar and wind because Spain and Portugal lost power for a few hours.

“But we should learn that grid design, policy and risk mapping aren’t yet up to the task of handling too much power from renewable sources.”

The post Q&A: What we do – and do not – know about the blackout in Spain and Portugal appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: What we do – and do not – know about the blackout in Spain and Portugal

Climate Change

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

The country’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas benefited from what critics say is a questionable IRS interpretation of tax credits.

Cheniere Energy, the largest producer and exporter of U.S. liquefied natural gas, received $370 million from the IRS in the first quarter of 2026, a payout that shipping experts, tax specialists and a U.S. senator say the company never should have received.

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

Climate Change

DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Absolute State of the Union

‘DRILL, BABY’: US president Donald Trump “doubled down on his ‘drill, baby, drill’ agenda” in his State of the Union (SOTU) address, said the Los Angeles Times. He “tout[ed] his support of the fossil-fuel industry and renew[ed] his focus on electricity affordability”, reported the Financial Times. Trump also attacked the “green new scam”, noted Carbon Brief’s SOTU tracker.

COAL REPRIEVE: Earlier in the week, the Trump administration had watered down limits on mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants, reported the Financial Times. It remains “unclear” if this will be enough to prevent the decline of coal power, said Bloomberg, in the face of lower-cost gas and renewables. Reuters noted that US coal plants are “ageing”.

OIL STAY: The US Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments brought by the oil industry in a “major lawsuit”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper said the firms are attempting to head off dozens of other lawsuits at state level, relating to their role in global warming.

SHIP-SHILLING: The Trump administration is working to “kill” a global carbon levy on shipping “permanently”, reported Politico, after succeeding in delaying the measure late last year. The Guardian said US “bullying” could be “paying off”, after Panama signalled it was reversing its support for the levy in a proposal submitted to the UN shipping body.

Around the world

- RARE EARTHS: The governments of Brazil and India signed a deal on rare earths, said the Times of India, as well as agreeing to collaborate on renewable energy.

- HEAT ROLLBACK: German homes will be allowed to continue installing gas and oil heating, under watered-down government plans covered by Clean Energy Wire.

- BRAZIL FLOODS: At least 53 people died in floods in the state of Minas Gerais, after some areas saw 170mm of rain in a few hours, reported CNN Brasil.

- ITALY’S ATTACK: Italy is calling for the EU to “suspend” its emissions trading system (ETS) ahead of a review later this year, said Politico.

- COOKSTOVE CREDITS: The first-ever carbon credits under the Paris Agreement have been issued to a cookstove project in Myanmar, said Climate Home News.

- SAUDI SOLAR: Turkey has signed a “major” solar deal that will see Saudi firm ACWA building 2 gigawatts in the country, according to Agence France-Presse.

$467 billion

The profits made by five major oil firms since prices spiked following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine four years ago, according to a report by Global Witness covered by BusinessGreen.

Latest climate research

- Claims about the “fingerprint” of human-caused climate change, made in a recent US Department of Energy report, are “factually incorrect” | AGU Advances

- Large lakes in the Congo Basin are releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere from “immense ancient stores” | Nature Geoscience

- Shared Socioeconomic Pathways – scenarios used regularly in climate modelling – underrepresent “narratives explicitly centring on democratic principles such as participation, accountability and justice” | npj Climate Action

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

The constituency of Richard Tice MP, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of Reform UK, is the second-largest recipient of flood defence spending in England, according to new Carbon Brief analysis. Overall, the funding is disproportionately targeted at coastal and urban areas, many of which have Conservative or Liberal Democrat MPs.

Spotlight

Is there really a UK ‘greenlash’?

This week, after a historic Green Party byelection win, Carbon Brief looks at whether there really is a “greenlash” against climate policy in the UK.

Over the past year, the UK’s political consensus on climate change has been shattered.

Yet despite a sharp turn against climate action among right-wing politicians and right-leaning media outlets, UK public support for climate action remains strong.

Prof Federica Genovese, who studies climate politics at the University of Oxford, told Carbon Brief:

“The current ‘war’ on green policy is mostly driven by media and political elites, not by the public.”

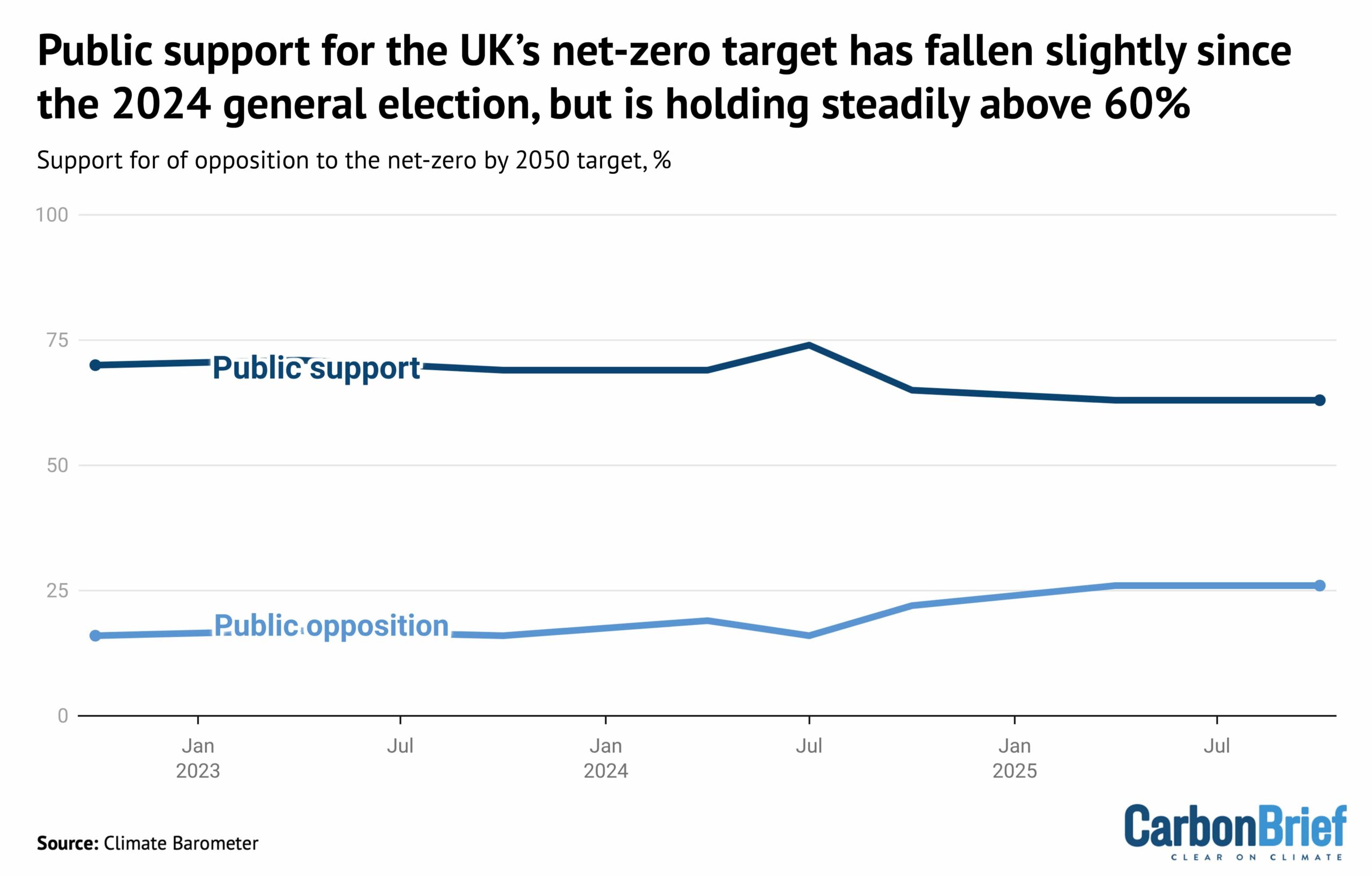

Indeed, there is still a greater than two-to-one majority among the UK public in favour of the country’s legally binding target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, as shown below.

Steve Akehurst, director of public-opinion research initiative Persuasion UK, also noted the growing divide between the public and “elites”. He told Carbon Brief:

“The biggest movement is, without doubt, in media and elite opinion. There is a bit more polarisation and opposition [to climate action] among voters, but it’s typically no more than 20-25% and mostly confined within core Reform voters.”

Conservative gear shift

For decades, the UK had enjoyed strong, cross-party political support for climate action.

Lord Deben, the Conservative peer and former chair of the Climate Change Committee, told Carbon Brief that the UK’s landmark 2008 Climate Change Act had been born of this cross-party consensus, saying “all parties supported it”.

Since their landslide loss at the 2024 election, however, the Conservatives have turned against the UK’s target of net-zero emissions by 2050, which they legislated for in 2019.

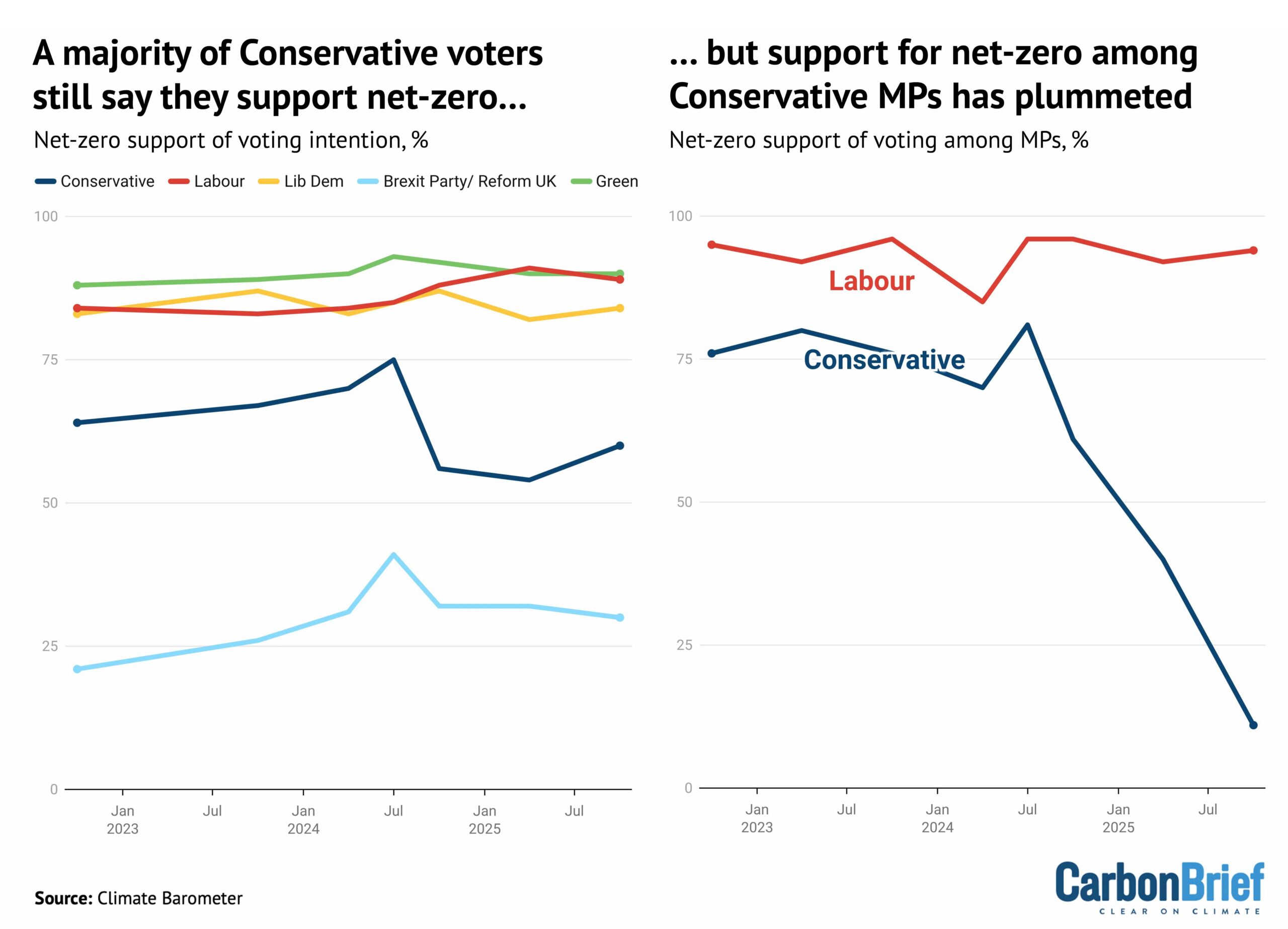

Curiously, while opposition to net-zero has surged among Conservative MPs, there is majority support for the target among those that plan to vote for the party, as shown below.

Dr Adam Corner, advisor to the Climate Barometer initiative that tracks public opinion on climate change, told Carbon Brief that those who currently plan to vote Reform are the only segment who “tend to be more opposed to net-zero goals”. He said:

“Despite the rise in hostile media coverage and the collapse of the political consensus, we find that public support for the net-zero by 2050 target is plateauing – not plummeting.”

Reform, which rejects the scientific evidence on global warming and campaigns against net-zero, has been leading the polls for a year. (However, it was comfortably beaten by the Greens in yesterday’s Gorton and Denton byelection.)

Corner acknowledged that “some of the anti-net zero noise…[is] showing up in our data”, adding:

“We see rising concerns about the near-term costs of policies and an uptick in people [falsely] attributing high energy bills to climate initiatives.”

But Akehurst said that, rather than a big fall in public support, there had been a drop in the “salience” of climate action:

“So many other issues [are] competing for their attention.”

UK newspapers published more editorials opposing climate action than supporting it for the first time on record in 2025, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Global ‘greenlash’?

All of this sits against a challenging global backdrop, in which US president Donald Trump has been repeating climate-sceptic talking points and rolling back related policy.

At the same time, prominent figures have been calling for a change in climate strategy, sold variously as a “reset”, a “pivot”, as “realism”, or as “pragmatism”.

Genovese said that “far-right leaders have succeeded in the past 10 years in capturing net-zero as a poster child of things they are ‘fighting against’”.

She added that “much of this is fodder for conservative media and this whole ecosystem is essentially driving what we call the ‘greenlash’”.

Corner said the “disconnect” between elite views and the wider public “can create problems” – for example, “MPs consistently underestimate support for renewables”. He added:

“There is clearly a risk that the public starts to disengage too, if not enough positive voices are countering the negative ones.”

Watch, read, listen

TRUMP’S ‘PETROSTATE’: The US is becoming a “petrostate” that will be “sicker and poorer”, wrote Financial Times associate editor Rana Forohaar.

RHETORIC VS REALITY: Despite a “political mood [that] has darkened”, there is “more green stuff being installed than ever”, said New York Times columnist David Wallace-Wells.

CHINA’S ‘REVOLUTION’: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast reported from China on the “green energy revolution” taking place in the country.

Coming up

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean, Brasília

- 3 March: UK spring statement

- 4-11 March: China’s “two sessions”

- 5 March: Nepal elections

Pick of the jobs

- The Guardian, senior reporter, climate justice | Salary: $123,000-$135,000. Location: New York or Washington DC

- China-Global South Project, non-resident fellow, climate change | Salary: Up to $1,000 a month. Location: Remote

- University of East Anglia, PhD in mobilising community-based climate action through co-designed sports and wellbeing interventions | Salary: Stipend (unknown amount). Location: Norwich, UK

- TABLE and the University of São Paulo, Brazil, postdoctoral researcher in food system narratives | Salary: Unknown. Location: Pirassununga, Brazil

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

Seven Pacific island nations say they will demand heftier levies on global shipping emissions if opponents of a green deal for the industry succeed in reopening negotiations on the stalled accord.

The United States and Saudi Arabia persuaded countries not to grant final approval to the International Maritime Organization’s Net-Zero Framework (NZF) in October and they are now leading a drive for changes to the deal.

In a joint submission seen by Climate Home News, the seven climate-vulnerable Pacific countries said the framework was already a “fragile compromise”, and vowed to push for a universal levy on all ship emissions, as well as higher fees . The deal currently stipulates that fees will be charged when a vessel’s emissions exceed a certain level.

“For many countries, the NZF represents the absolute limit of what they can accept,” said the unpublished submission by Fiji, Kiribati, Vanuatu, Nauru, Palau, Tuvalu and the Solomon Islands.

The countries said a universal levy and higher charges on shipping would raise more funds to enable a “just and equitable transition leaving no country behind”. They added, however, that “despite its many shortcomings”, the framework should be adopted later this year.

US allies want exemption for ‘transition fuels’

The previous attempt to adopt the framework failed after governments narrowly voted to postpone it by a year. Ahead of the vote, the US threatened governments and their officials with sanctions, tariffs and visa restrictions – and President Donald Trump called the framework a “Green New Scam Tax on Shipping”.

Since then, Liberia – an African nation with a major low-tax shipping registry headquartered in the US state of Virginia – has proposed a new measure under which, rather than staying fixed under the NZF, ships’ emissions intensity targets change depending on “demonstrated uptake” of both “low-carbon and zero-carbon fuels”.

The proposal places stringent conditions on what fuels are taken into consideration when setting these targets, stressing that the low- and zero-carbon fuels should be “scalable”, not cost more than 15% more than standard marine fuels and should be available at “sufficient ports worldwide”.

This proposal would not “penalise transitional fuels” like natural gas and biofuels, they said. In the last decade, the US has built a host of large liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals, which the Trump administration is lobbying other countries to purchase from.

The draft motion, seen by Climate Home News, was co-sponsored by US ally Argentina and also by Panama, a shipping hub whose canal the US has threatened to annex. Both countries voted with the US to postpone the last vote on adopting the framework.

The IMO’s Panamanian head Arsenio Dominguez told reporters in January that changes to the framework were now possible.

“It is clear from what happened last year that we need to look into the concerns that have been expressed [and] … make sure that they are somehow addressed within the framework,” he said.

Patchwork of levies

While the European Union pushed firmly for the framework’s adoption, two of its shipping-reliant member states – Greece and Cyprus – abstained in October’s vote.

After a meeting between the Greek shipping minister and Saudi Arabia’s energy minister in January, Greece said a “common position” united Greece, Saudi Arabia and the US on the framework.

If the NZF or a similar instrument is not adopted, the IMO has warned that there will be a patchwork of differing regional levies on pollution – like the EU’s emissions trading system for ships visiting its ports – which will be complicated and expensive to comply with.

This would mean that only countries with their own levies and with lots of ships visiting their ports would raise funds, making it harder for other nations to fund green investments in their ports, seafarers and shipping companies. In contrast, under the NZF, revenues would be disbursed by the IMO to all nations based on set criteria.

Anais Rios, shipping policy officer from green campaign group Seas At Risk, told Climate Home News the proposal by the Pacific nations for a levy on all shipping emissions – not just those above a certain threshold – was “the most credible way to meet the IMO’s climate goals”.

“With geopolitics reframing climate policy, asking the IMO to reopen the discussion on the universal levy is the only way to decarbonise shipping whilst bringing revenue to manage impacts fairly,” Rios said.

“It is […] far stronger than the Net-Zero Framework that is currently on offer.”

The post Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen appeared first on Climate Home News.

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits