Global warming of 2C would see “extensive, long-term [and] essentially irreversible” losses from the Earth’s ice sheets and glaciers, warns a new report.

It would also lead to polar oceans that are “ice-free” in summer and suffering “essentially permanent corrosive ocean acidification”, the report says.

The 2023 “state of the cryosphere” report from the International Cryosphere Climate Initiative (ICCI) lays out the impacts on Earth’s frozen land and seas from sustained warming at 2C and the “catastrophic global damage” that would result.

These impacts would include “potentially rapid, irreversible sea level rise from the Earth’s ice sheets”, the report says, with a “compelling number of new studies” all pointing to thresholds of sustained ice loss for both Greenland and parts of Antarctica at well-below 2C.

This would commit the world to “between 12 and 20 metres” of sea level rise “if 2C becomes the new constant”.

Holding global warming of 2C would also not be enough to “prevent extensive permafrost thaw”, the authors say, bringing additional warming from the resulting CO2 and methane emissions. A 2C world would also see “widespread negative impacts on key fisheries and species” in polar and near-polar oceans.

First published in 2021, the focus of this year’s annual review on how 2C of warming is “too high” shows that the aspirational limit of 1.5C in the Paris Agreement “is not merely preferable to 2C”, but “the only option”, the report says.

The ICCI’s Dr James Kirkham, chief science advisor at the Ambition on Melting Ice high-level group, tells Carbon Brief that the conclusion that 2C is too high for the cryosphere “won’t come as a surprise at all” to most scientists.

With COP28 in Dubai coming later this month, Kirkham says it is time to make “crystal clear” that “2C must now be seen as an unacceptable outcome for the world because of the impacts from the cryosphere”.

In this Q&A, Carbon Brief unpacks the report’s findings for the world’s ice sheets, mountain glaciers, permafrost, sea ice and polar oceans.

- How can ‘very low’ emissions slow impacts on the cryosphere?

- Is the ‘true guardrail’ for preventing dangerous sea level rise actually 1C?

- Is today’s climate already too warm to preserve some mountain glaciers?

- What impact could permafrost emissions have on the carbon budget?

- What are the prospects for sea ice at the Earth’s poles?

- What do rising temperatures and CO2 mean for the polar oceans?

How can ‘very low’ emissions slow impacts on the cryosphere?

Past emissions of CO2 and other greenhouse gases (GHGs) have “pushed the planet into a risk zone”, the report warns, with very visible impacts on the cryosphere:

“Today’s 1.2C above pre-industrial already has caused massive drops in Arctic and Antarctic sea ice; loss of glacier ice in all regions across the planet; accelerating loss from both the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets; extensive permafrost thaw; and rising polar ocean acidification.”

The implications of these changes stretch beyond the Earth’s poles and mountain regions, the authors note, from accelerating sea level rise and disturbed ocean currents to declining water resources and greater carbon emissions.

Nearly all of these changes “cannot be reversed on human timescales”, the authors warn, and they will continue to grow with each additional 10th of a degree of temperature rise.

Kirkham likens the way the cryosphere responds to warming to a “bowling ball once thrown”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“The changes will continue to roll on long after its initial climatic push because the system has momentum.

“[This means] that many of the long-term challenges associated with the cryosphere are on the cusp of being locked in by decisions made by policymakers in the next few years, and the awareness in the policy world of this ‘lock in’ appears lost right now.”

While the aim of restricting global warming to “well-below” 2C is set out in the Paris Agreement, the report says the “physical reality” of the cryosphere’s response to warming means these changes “would become devastating” well before 2C is reached.

However, warming of 2C is not a “predetermined outcome”, the authors say, arguing that “only a strong, emergency scale course-correction towards 1.5C…can avert higher temperatures, to slow and eventually halt these cryosphere impacts within adaptable levels”.

A “very low” future emissions pathway that would keep warming within, or very close to, 1.5C – the more stringent part of the Paris goal – remains “physically, technologically and economically feasible”, the report says.

This is the “SSP1-1.9” pathway from the set of Shared Socioeconomic Pathways (SSPs) used in the sixth assessment report (AR6) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Under this pathway (see table below), fossil fuel emissions decline 40% by 2030 and global warming peaks at 1.6C before declining to around 1.4C by the end of the century.

| Emissions pathway | Pathway name | Median global warming in 2100 | CO2 levels in 2100 (parts per million) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Very low | SSP1-1.9 | 1.4C (after brief 1.5C overshoot) | 440 ppm |

| Low | SSP1-2.6 | 1.8C (and declining) | 450 ppm |

| Intermediate | SSP2-4.5 | 2.7C (and rising) | 650 ppm |

| High | SSP3-7.0 | 3.6C (and rising) | 800 ppm |

| Very high | SSP5-8.5 | 4.4C (and rising) | 1,000+ ppm |

IPCC AR6 emissions pathways. Credit: ICCI (2023)

Under very low emissions, the Earth’s cryosphere would “generally [begin] to stabilise in 2040-80”, the report says:

“Slow CO2 and methane emissions from permafrost continue for one-two centuries, then cease. Snowpack stabilises, though at lower levels than today. Steep glacier loss continues for several decades, but slows by 2100; some glaciers still will be lost, but others begin to show regrowth. Arctic sea ice stabilises slightly above complete summer loss. Year-round corrosive waters for shelled life are limited to scattered polar and near-polar regions for several thousand years.”

In addition, while “ice sheet loss and sea level rise will continue for several hundred to thousands of years due to ocean warming”, the authors say, it will “likely not exceed three metres globally and occur over centuries”.

All other emissions pathways, including “low” emissions where warming peaks at 1.8C, would “result in far greater committed global loss and damage from [the] cryosphere, continuing over several centuries”, the report warns.

Is the ‘true guardrail’ for preventing dangerous sea level rise actually 1C?

The Earth’s ice sheets on Greenland and Antarctica together hold enough ice to raise global sea levels by 65 metres. The risks of significant amounts of this ice being lost irreversibly on human timescales “increase as temperature and rates of warming rise”, the authors say.

When the ice sheets are in equilibrium, melting ice and the breaking off of icebergs are balanced by mass gain through snowfall. However, “observations now confirm that this equilibrium has been lost” on Greenland, West Antarctica, the Antarctic Peninsula and potentially for portions of East Antarctica, the report says.

This is illustrated in the maps below, which show the gain (blue) and loss (red) in ice on Greenland (left) and Antarctica (right) between 2003 and 2019.

Today, the loss of ice from Greenland is “three times what it was 20 years ago”, the report notes, while Antarctica’s contribution to sea level rise is “six times greater than it was 30 years ago”.

The report paints a bleak picture for the future of both ice sheets. It notes that a “compelling number of new studies” all point to thresholds where irreversible melt becomes inevitable for both Greenland and parts of Antarctica at well below 2C of warming.

This means that were 2C of warming to become “the new constant Earth temperature”, the planet would be committed to between 12 and 20 metres of sea level rise.

For example, evidence from proxy data suggests that, in Earth’s distant past, such thresholds have occurred at around 1C for West Antarctica and the Antarctic Peninsula and between 1.5C and 2C for Greenland, the report says. (These contain enough ice to raise sea levels by around five and seven metres, respectively.) It adds:

“It should be noted that changes around past thresholds were driven by slow increases in atmospheric greenhouse gases, but were paced by slow changes in Earth’s orbit – unlike today’s rapid, human-caused rates of change.”

As a result, “many ice sheet scientists now believe that by 2C, nearly all of Greenland, much of West Antarctica, and even vulnerable portions of East Antarctica will be triggered to very long-term, inexorable sea level rise”.

This occurs because a warmer ocean “will hold heat longer than the atmosphere”, in addition to “a number of self-reinforcing feedback mechanisms, so that it takes much longer for ice sheets to regrow (tens of thousands of years) than to lose their ice”.

This means that “once ice sheet melt accelerates due to higher temperatures, it cannot be stopped or reversed for many thousands of years” – even if temperatures stabilise or even decrease should the world reduce carbon emissions to net-zero, the authors warn.

Lowering sea level rise from newly reached highs would thus “not occur until temperatures go well below pre-industrial, initiating a slow ice sheet regrowth”, the report says:

“Overshooting the Paris Agreement [goal] would therefore cause essentially permanent loss and damage to the Earth’s ice sheets, with widespread impacts that are not reversible on human timescales.”

The report includes the chart below from a 2023 study, which highlights the long-term consequences of global warming. It shows projected global temperature change (top) and the implications for sea level rise (bottom) out to 2150 under four different SSPs.

Under “intermediate” emissions (SSP2-4.5, pink line), which most closely matches the path that the world is on today, sea levels continue to rise. Only “very low” emissions (SSP1-1.9, blue line) would slow and stabilise sea level rise, the report says, “preserving many coastal communities and giving others time to adapt”.

In the face of this evidence, “for a growing number of ice sheet experts”, the true “guardrail” to prevent dangerous levels and rates of sea level rise is “not 2C or even 1.5C, but 1C above pre-industrial”, the report concludes.

Staying as close as possible to the 1.5C limit will “allow us to return more quickly to the 1C level”, the authors say, “drastically slowing global impacts from ice sheet loss and especially West Antarctic ice sheet collapse”.

This would “reduce the risk of locking in significant amounts of long-term, irreversible sea level rise”, the report says. It would also “provide low-lying nations and communities more time to adapt through sustainable development, although some level of managed retreat from coastlines in the long-term is tragically inevitable”.

For world leaders, not committing to reducing emissions in line with the 1.5C limit is “de facto making a decision to erase many coastlines, displacing hundreds of millions of people – perhaps much sooner than we think”, the authors warn.

Is today’s climate already too warm to preserve some mountain glaciers?

Nearly all glaciers in the north Andes, east Africa and Indonesia – along with most mid-latitude glaciers outside the Himalaya and polar regions – could disappear if the 2C warming threshold is breached, the report warns.

Many of these glaciers are “disappearing too rapidly to be saved” even in the present climate and could be gone by 2050, while those large enough to survive the century have “already passed a point of no return”, according to the report’s latest projections.

The figure below shows projections of how much ice glaciers in tropical regions would retain, on average, over the next few centuries under different warming levels in 2100. The lines show the impact of warming by 10ths of a degree between 1.4C and 3C.

At 2C, even the Himalayas are slated to lose around half of today’s ice on average, the report estimates. In a very high emissions scenario, 70-80% of the current glacier volume in the Hindu Kush Himalaya could disappear by 2100, the report says, while low emissions would limit glacier loss to 30%.

Without human-induced warming, glaciers in the northern Andes could have served as a reliable source of water for “hundreds of thousands” of years, the report states. Their loss stands to particularly impact villages in northern Peru, Chile and Bolivia and major cities such as La Paz.

This threat to water security is “one of the greatest challenges posed by a melting cryosphere in a 2C world”, Dr Kirkham tells Carbon Brief, “especially in Asia where freshwater sourced from snow and ice provides a lifeline to over 2 billion people”. He adds:

“This loss of water will even impact some downstream countries that do not contain any snow and ice at all, such as Bangladesh, especially in years when the timing of the monsoon is unreliable.”

Mid-latitude glaciers in the Alps, the Rockies, the southern Andes, Patagonia, Scandinavia and New Zealand are also seeing severe losses.

The report quotes new findings in 2023 showing that the Swiss Alps lost 10% of its glacial ice in just two years over 2022-23, attributed especially to heatwaves, while the Andes witnessed “what may have been the most extreme heatwave on the planet in 2023” in winter.

Warmer temperatures at higher altitudes mean what should be snow is now falling as hazardous extreme rainfall, while other mountain areas face “snow droughts”.

The report finds that most glacier-covered regions outside the Himalaya and the poles have already passed a period of “peak water”, a point at which water availability will only decline each season.

Recovering lost glaciers could take hundreds to thousands of years and temperatures well below the records being set today, the authors note.

However, a low emissions scenario could limit glacier loss in the Himalaya to 30%, with steeper emission cuts stabilising high mountain Asia’s snowpack and glaciers. Some glaciers could eventually even begin to return, the report says.

Rapid cuts consistent with 1.5C of warming could preserve twice as much ice in Central Asia and the southern Andes, the report estimates.

This could benefit vulnerable communities that depend most on glacial water runoff for drinking water and subsistence agriculture while buying them time to adapt to dangerous climate impacts. For instance, one study cited by the report estimates that 15 million people across the world and especially in high mountain Asia and Peru are at risk of glacial lake outburst floods (GLOFs).

A very low emissions pathway could have benefits for cities and economies beyond agriculture, the report notes. The megacities of Delhi, Los Angeles, Marrakech and Kathmandu are all dependent on meltwater, to a degree, while new research shows growing climate-driven threats to hydropower projects in high mountain Asia due to retreating glaciers, thawing permafrost, GLOFs, avalanches and landslides.

Dealing with the changing water supply from glaciers and snow “may render many of these investments defunct before some of the projects are completed”, warns Kirkham.

Countries including Japan, the US and Switzerland also stand to lose significant revenues from snow-based tourism, while also being exposed to increased risk of wildfires and mudslides linked to the lack of snow cover.

The figure below contrasts the state of Switzerland’s Great Aletsch glacier today – the largest glacier in the Alps – with projections under current emissions and very low emissions scenarios in 2060 and 2100.

However, if warming were limited to 1.5C, the annual snowpack could stabilise – even if at a lower average amount than today. It adds:

“This visible snow and ice preservation, and its benefits for freshwater resources, may be one of the earliest and visible signs to humanity that steps towards low emissions have meaningful results.”

Dr Miriam Jackson, senior cryosphere specialist at the International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD) and author on the mountain glaciers chapter of the report, tells Carbon Brief:

“This latest cryosphere report shows, more clearly than ever, that we have a choice. We can continue as we are now and see 80% of glacier loss by the end of this century. Or we can follow a very low emissions pathway, where glaciers and snow cover in high mountain Asia stabilise and eventually begin to return. Millions of people’s livelihoods depend on us making the second choice.”

What impact could permafrost emissions have on the carbon budget?

A global temperature rise of 2C – “and even 1.5C” – is too high to prevent the widespread thawing of an icy layer spread across more than one-fifth of the northern hemisphere’s land, the report says.

Permafrost is a mixture of soil, rock and other materials on or under the Earth’s surface that has been frozen for at least two years. It stores a huge amount of ancient, organic carbon.

Research shows that permafrost areas are rapidly warming and, as a result, thawing. This process releases some of the stored carbon into the atmosphere as CO2 and methane, further fuelling global warming. This is known as a “positive feedback”.

“These emissions are irreversibly set in motion”, the report says, and will not slow for one-to-two centuries even if permafrost re-freezes at a later point.

This means that permafrost emissions can further diminish the remaining global “carbon budget” – the amount of CO2 that can still be released while keeping warming below global limits of 1.5 or 2C.

The report says that carbon budget calculations “must take these indirect human-caused emissions from permafrost thaw into account…not just through [to] 2100, but well into the future”. It adds:

“Permafrost emissions today and in the future are on the same scale as large industrial countries, but can be minimised if the planet remains at lower temperatures.”

The chart below shows the impact of permafrost emissions (pink shaded areas) on the remaining carbon budget (red bars) to stay within 1.5C and 2C of warming. Taking permafrost emissions into account significantly reduces the budget estimates, the report says.

Prof Julie Brigham-Grette, the geosciences graduate programme director at the University of Massachusetts Amherst and author on the report, says she is “very concerned” about permafrost thaw. She tells Carbon Brief:

“The bottom line is that we must reduce fossil fuel use urgently to slow down the demise of glaciers, ice sheets, permafrost, snow cover, sea ice…The climate crisis is real and it’s a threat-multiplier to social and political systems around the world.”

Currently, at 1.2C of warming, the annual emissions from permafrost are about the same as Japan – the sixth largest emitting country, based on 2019 figures, the report says.

Keeping temperatures below 1.4C would prevent “most additional new thaw”, the report says. But even at 1.5C, scientists predict a 40% loss of near-surface permafrost areas by 2100.

At a 2C global temperature rise, permafrost thawing and associated emissions would continue to climb.

At temperatures of 3C or higher by the end of this century, “much of the Arctic, and nearly all mountain” permafrost would reach the “thawed state”, where it would produce the equivalent of the combined annual GHG emissions of the US and the EU in 2019, for centuries, the report says.

As much as half of recent permafrost thaw occurred during extreme temperature events that were up to 12C above average, the authors say.

But the report notes that current global climate models do not include these “abrupt thaw” processes in their predictions. Scientists are “still working on these phenomena and what it means for emission rates”, Brigham-Grette says.

Studies analysed in the report found that, overall, permafrost thaw will have a number of “cascading impacts” with “severe” effects already being felt in the Arctic. The report adds:

“Thawing permafrost is causing the loss of Arctic lands, threatening cultural and subsistence resources, and damaging infrastructure, like roads, pipelines and houses, as the ground sinks unevenly beneath them.”

The “only means available” to reduce the problem is to “keep as much permafrost as possible in its current frozen state” and limiting global warming to 1.5C, according to the report.

What are the prospects for sea ice at the Earth’s poles?

Sea ice at the Earth’s poles undergoes an annual cycle of melting and regrowth. In the Arctic, sea ice melts during the warmer summer months towards its September minimum, before regrowing in the colder winter months. However, as the planet warms, sea ice extent at the September minimum is declining.

The area of Arctic sea ice that “survives” the summer has declined by at least 40% since 1979, the report says. Furthermore, it says, the Arctic ocean has “become dominated by a thinner, faster moving covering of seasonal ice, which typically doesn’t survive the summer”, as opposed to thick, multiyear sea ice.

The authors add:

“Ninety percent of Arctic sea ice loss can be directly attributed to anthropogenic emissions. A threshold has now been crossed in which ice-free conditions in the month of September will occur at times even with very low emissions, and with much slower and later surface freeze-up.”

There is widespread public and scientific interest in when the Arctic might see its first “ice-free” summer. The report highlights a recent study that suggests Arctic sea ice is more sensitive to GHG emissions than was described in the IPCC AR6 report.

The figure below shows projections of September Arctic sea ice area for different emissions scenarios. The different coloured lines indicate different models and the horizontal red line shows the threshold for a “practically ice-free” Arctic, which is one million square kilometres of ice. The lowest emission scenario is shown on the left and the highest emission scenario on the right.

The graphic shows that only the SSP1-1.9 scenario results in “sea ice recovery above ice-free conditions”. At 2C warming, the Arctic Ocean will be sea ice-free in summer “almost every year”, the report says.

The report concludes that the occurrence of the first ice-free Arctic summer is “unpredictable”, but “inevitable”, adding that it is likely to occur at least once before 2050 even under a “very low” emissions scenario.

Dr Zachary Labe is a postdoctoral research associate at the NOAA Geophysical Fluid Dynamics Laboratory and the Atmospheric and Oceanic Sciences Program at Princeton University, and was not involved in writing the report.

He praises the report, but adds:

“There are countless studies that have evaluated future Arctic sea ice trajectories using models and emergent constraint-like methods, so I advise caution in overly relying on mostly one new study.”

At the Earth’s other pole, Antarctic sea ice saw record-breaking melt in 2023 setting a summer minimum in February 2023. “The unprecedented reduction in Antarctic sea ice extent since 2016 represents a regime shift to a new state of inevitable decline caused by ocean warming,” the authors say.

According to the report, sea ice projections around Antarctica are “considerably less certain” than those in the Arctic. However, the authors say the record-low conditions in 2023 “indicate that its threshold for complete summer sea ice loss might be even lower than for the Arctic”.

The authors also highlight recent research that found thousands of emperor penguin chicks died because of the early breakup of Antarctic sea ice in 2022.

“Perhaps more so than for any other part of the cryosphere, 2C is far too high to prevent extensive sea ice loss at both poles, with severe feedbacks to global weather and climate,” the authors conclude.

What do rising temperatures and CO2 mean for the polar oceans?

The world’s oceans absorb around one-quarter of all human-produced CO2, which reacts with seawater to produce a weak acid in a process called ocean acidification.

Rates of ocean acidification are currently faster than they have been at any point in the past 300m years, the report finds. Polar waters in the Arctic and Southern oceans have absorbed up to 60% of the carbon taken up by the world’s oceans so far, because colder and fresher waters can hold more carbon, it notes, adding:

“The Arctic Ocean appears to be most sensitive: already today, it has large regions of persistent corrosive waters.”

In 2008, a group of scientists identified atmospheric CO2 levels of 450 parts per million (ppm) as an important threshold for “serious global ocean acidification”, according to the report. This atmospheric CO2 threshold corresponds to around 1.5C warming, it says.

However, it says that current national pledges to reduce emissions under the Paris Agreement – even if completely fulfilled – will result in CO2 levels above 500ppm, resulting in temperatures of around 2.1C.

The maps below show ocean acidification in scenarios of 3-4C (top) and a 1.5C (bottom) of warming by 2100. Red shading shows “undersaturated aragonite conditions” – a measure of ocean acidification meaning that shelled organisms have difficulty building or maintaining their shells. Darker red indicates greater levels of ocean acidification.

“There is currently no practical way for humans to reverse ocean acidification,” the authors warn, adding that it will take some 30-70,000 years to bring acidification and its impacts back to pre-industrial levels.

As polar oceans become more acidic, they are also warming at an “unusually rapid” rate, the report warns. The authors note that since 1982, summer surface water temperatures in the Arctic have increased by around 2C – mainly due to sea-ice loss that allows the sun’s rays to hit the water, and an inflow of warmer water from lower latitudes.

The map below shows the change in sea surface temperature over 1993-2021. Red indicates warming and blue indicates cooling, while the white at the highest polar latitudes is due to incomplete data for this period.

The map shows that near-polar waters such as the Barents Sea have warmed “extensively” over the past two decades. The colder patch in the south of Greenland is an exception which is partly due to cold freshwater being added as the Greenland ice sheet melts, it adds.

The authors add that increased run-off from glaciers, ice sheets and rivers is also affecting global ocean circulation, which could stall ocean currents such as the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC).

The report also warns that the dual impacts of ocean acidification and warming could have severe impacts for polar biodiversity, adding that “polar waters contain some of the world’s richest fisheries and most diverse marine ecosystems”.

Over the past decade, many polar species have experienced “lethal” temperatures which have caused mass-die offs, the report warns.

It also highlights the dangers of ocean acidification, including harm to key ocean-dwelling organisms which could “cascade” up the food chain. “Compound events combining marine heatwaves and extreme acidification have already caused population crashes even at today’s 1.2C,” the authors say.

The report concludes:

“2C will result in year-round, essentially permanent corrosive conditions in extensive regions of Earth’s polar and some near-polar seas; with widespread negative impacts on key fisheries and species.”

The post Q&A: Warming of 2C would trigger ‘catastrophic’ loss of world’s ice, new report says appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: Warming of 2C would trigger ‘catastrophic’ loss of world’s ice, new report says

Climate Change

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter.

Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Food inflation on the rise

DELUGE STRIKES FOOD: Extreme rainfall and flooding across the Mediterranean and north Africa has “battered the winter growing regions that feed Europe…threatening food price rises”, reported the Financial Times. Western France has “endured more than 36 days of continuous rain”, while farmers’ associations in Spain’s Andalusia estimate that “20% of all production has been lost”, it added. Policy expert David Barmes told the paper that the “latest storms were part of a wider pattern of climate shocks feeding into food price inflation”.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “Cropped” email newsletter. A fortnightly digest of food, land and nature news and views. Sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

NO BEEF: The UK’s beef farmers, meanwhile, “face a double blow” from climate change as “relentless rain forces them to keep cows indoors”, while last summer’s drought hit hay supplies, said another Financial Times article. At the same time, indoor growers in south England described a 60% increase in electricity standing charges as a “ticking timebomb” that could “force them to raise their prices or stop production, which will further fuel food price inflation”, wrote the Guardian.

‘TINDERBOX’ AND TARIFFS: A study, covered by the Guardian, warned that major extreme weather and other “shocks” could “spark social unrest and even food riots in the UK”. Experts cited “chronic” vulnerabilities, including climate change, low incomes, poor farming policy and “fragile” supply chains that have made the UK’s food system a “tinderbox”. A New York Times explainer noted that while trade could once guard against food supply shocks, barriers such as tariffs and export controls – which are being “increasingly” used by politicians – “can shut off that safety valve”.

El Niño looms

NEW ENSO INDEX: Researchers have developed a new index for calculating El Niño, the large-scale climate pattern that influences global weather and causes “billions in damages by bringing floods to some regions and drought to others”, reported CNN. It added that climate change is making it more difficult for scientists to observe El Niño patterns by warming up the entire ocean. The outlet said that with the new metric, “scientists can now see it earlier and our long-range weather forecasts will be improved for it.”

WARMING WARNING: Meanwhile, the US Climate Prediction Center announced that there is a 60% chance of the current La Niña conditions shifting towards a neutral state over the next few months, with an El Niño likely to follow in late spring, according to Reuters. The Vibes, a Malaysian news outlet, quoted a climate scientist saying: “If the El Niño does materialise, it could possibly push 2026 or 2027 as the warmest year on record, replacing 2024.”

CROP IMPACTS: Reuters noted that neutral conditions lead to “more stable weather and potentially better crop yields”. However, the newswire added, an El Niño state would mean “worsening drought conditions and issues for the next growing season” to Australia. El Niño also “typically brings a poor south-west monsoon to India, including droughts”, reported the Hindu’s Business Line. A 2024 guest post for Carbon Brief explained that El Niño is linked to crop failure in south-eastern Africa and south-east Asia.

News and views

- DAM-AG-ES: Several South Korean farmers filed a lawsuit against the country’s state-owned utility company, “seek[ing] financial compensation for climate-related agricultural damages”, reported United Press International. Meanwhile, a national climate change assessment for the Philippines found that the country “lost up to $219bn in agricultural damages from typhoons, floods and droughts” over 2000-10, according to Eco-Business.

- SCORCHED GRASS: South Africa’s Western Cape province is experiencing “one of the worst droughts in living memory”, which is “scorching grass and killing livestock”, said Reuters. The newswire wrote: “In 2015, a drought almost dried up the taps in the city; farmers say this one has been even more brutal than a decade ago.”

- NOUVELLE VEG: New guidelines published under France’s national food, nutrition and climate strategy “urged” citizens to “limit” their meat consumption, reported Euronews. The delayed strategy comes a month after the US government “upended decades of recommendations by touting consumption of red meat and full-fat dairy”, it noted.

- COURTING DISASTER: India’s top green court accepted the findings of a committee that “found no flaws” in greenlighting the Great Nicobar project that “will lead to the felling of a million trees” and translocating corals, reported Mongabay. The court found “no good ground to interfere”, despite “threats to a globally unique biodiversity hotspot” and Indigenous tribes at risk of displacement by the project, wrote Frontline.

- FISH FALLING: A new study found that fish biomass is “falling by 7.2% from as little as 0.1C of warming per decade”, noted the Guardian. While experts also pointed to the role of overfishing in marine life loss, marine ecologist and study lead author Dr Shahar Chaikin told the outlet: “Our research proves exactly what that biological cost [of warming] looks like underwater.”

- TOO HOT FOR COFFEE: According to new analysis by Climate Central, countries where coffee beans are grown “are becoming too hot to cultivate them”, reported the Guardian. The world’s top five coffee-growing countries faced “57 additional days of coffee-harming heat” annually because of climate change, it added.

Spotlight

Nature talks inch forward

This week, Carbon Brief covers the latest round of negotiations under the UN Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD), which occurred in Rome over 16-19 February.

The penultimate set of biodiversity negotiations before October’s Conference of the Parties ended in Rome last week, leaving plenty of unfinished business.

The CBD’s subsidiary body on implementation (SBI) met in the Italian capital for four days to discuss a range of issues, including biodiversity finance and reviewing progress towards the nature targets agreed under the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF).

However, many of the major sticking points – particularly around finance – will have to wait until later this summer, leaving some observers worried about the capacity for delegates to get through a packed agenda at COP17.

The SBI, along with the subsidiary body on scientific, technical and technological advice (SBSTTA) will both meet in Nairobi, Kenya, later this summer for a final round of talks before COP17 kicks off in Yerevan, Armenia, on 19 October.

Money talks

Finance for nature has long been a sticking point at negotiations under the CBD.

Discussions on a new fund for biodiversity derailed biodiversity talks in Cali, Colombia, in autumn 2024, requiring resumed talks a few months later.

Despite this, finance was barely on the agenda at the SBI meetings in Rome. Delegates discussed three studies on the relationship between debt sustainability and implementation of nature plans, but the more substantive talks are set to take place at the next SBI meeting in Nairobi.

Several parties “highlighted concerns with the imbalance of work” on finance between these SBI talks and the next ones, reported Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

Lim Li Ching, senior researcher at Third World Network, noted that tensions around finance permeated every aspect of the talks. She told Carbon Brief:

“If you’re talking about the gender plan of action – if there’s little or no financial resources provided to actually put it into practice and implement it, then it’s [just] paper, right? Same with the reporting requirements and obligations.”

Monitoring and reporting

Closely linked to the issue of finance is the obligations of parties to report on their progress towards the goals and targets of the GBF.

Parties do so through the submission of national reports.

Several parties at the talks pointed to a lack of timely funding for driving delays in their reporting, according to ENB.

A note released by the CBD Secretariat in December said that no parties had submitted their national reports yet; by the time of the SBI meetings, only the EU had. It further noted that just 58 parties had submitted their national biodiversity plans, which were initially meant to be published by COP16, in October 2024.

Linda Krueger, director of biodiversity and infrastructure policy at the environmental not-for-profit Nature Conservancy, told Carbon Brief that despite the sparse submissions, parties are “very focused on the national report preparation”. She added:

“Everybody wants to be able to show that we’re on the path and that there still is a pathway to getting to 2030 that’s positive and largely in the right direction.”

Watch, read, listen

NET LOSS: Nigeria’s marine life is being “threatened” by “ghost gear” – nets and other fishing equipment discarded in the ocean – said Dialogue Earth.

COMEBACK CAUSALITY: A Vox long-read looked at whether Costa Rica’s “payments for ecosystem services” programme helped the country turn a corner on deforestation.

HOMEGROWN GOALS: A Straits Times podcast discussed whether import-dependent Singapore can afford to shelve its goal to produce 30% of its food locally by 2030.

‘RUSTING’ RIVERS: The Financial Times took a closer look at a “strange new force blighting the [Arctic] landscape”: rivers turning rust-orange due to global warming.

New science

- Lakes in the Congo Basin’s peatlands are releasing carbon that is thousands of years old | Nature Geoscience

- Natural non-forest ecosystems – such as grasslands and marshlands – were converted for agriculture at four times the rate of land with tree cover between 2005 and 2020 | Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences

- Around one-quarter of global tree-cover loss over 2001-22 was driven by cropland expansion, pastures and forest plantations for commodity production | Nature Food

In the diary

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean | Brasília

- 5 March: Nepal general elections

- 9-20 March: First part of the thirty-first session of the International Seabed Authority (ISA) | Kingston, Jamaica

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz.

Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Cropped 25 February 2026: Food inflation strikes | El Niño looms | Biodiversity talks stagnate

Climate Change

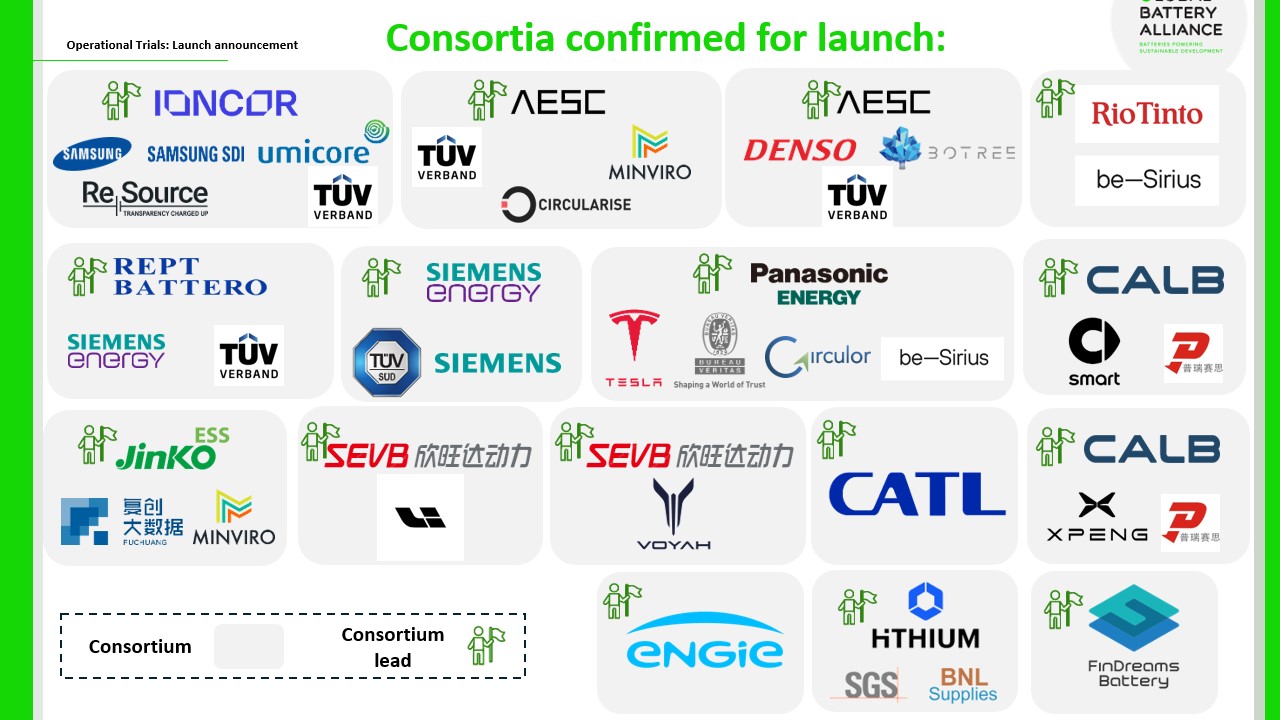

Battery passport plan aims to clean up the industry powering clean energy

For millions of consumers, the sustainability scheme stickers found on everything from bananas to chocolate bars and wooden furniture are a way to choose products that are greener and more ethical than some of the alternatives.

Inga Petersen, executive director of the Global Battery Alliance (GBA), is on a mission to create a similar scheme for one of the building blocks of the transition from fossil fuels to clean energy systems: batteries.

“Right now, it’s a race to the bottom for whoever makes the cheapest battery,” Petersen told Climate Home News in an interview.

The GBA is working with industry, international organisations, NGOs and governments to establish a sustainable and transparent battery value chain by 2030.

“One of the things we’re trying to do is to create a marketplace where products can compete on elements other than price,” Petersen said.

Under the GBA’s plan, digital product passports and traceability would be used to issue product-level sustainability certifications, similar to those commonplace in other sectors such as forestry, Petersen said.

Managing battery boom’s risks

Over the past decade, battery deployment has increased 20-fold, driven by record-breaking electric vehicle (EV) sales and a booming market for batteries to store intermittent renewable energy.

Falling prices have been instrumental to the rapid expansion of the battery market. But the breakneck pace of growth has exposed the potential environmental and social harms associated with unregulated battery production.

From South America to Zimbabwe and Indonesia, mineral extraction and refining has led to social conflict, environmental damage, human rights violations and deforestation. In Indonesia, the nickel industry is powered by coal while in Europe, production plants have been met with strong local opposition over pollution concerns.

“We cannot manage these risks if we don’t have transparency,” Petersen said.

The GBA was established in 2017 in response to concerns about the battery industry’s impact as demand was forecast to boom and reports of child labour in the cobalt mines of the Democratic Republic of the Congo made headlines.

The alliance’s initial 19 members recognised that the industry needed to scale rapidly but with “social, environmental and governance guardrails”, said Petersen, who previously worked with the UN Environment Programme to develop guiding principles to minimise the environmental impact of mining.

Digital battery passport

Today, the alliance is working to develop a global certification scheme that will recognise batteries that meet minimum thresholds across a set of environmental, social and governance benchmarks it has defined along the entire value chain.

Participating mines, manufacturing plants and recycling facilities will have to provide data for their greenhouse gas emissions as well as how they perform against benchmarks for assessing biodiversity loss, pollution, child and forced labour, community impacts and respect for the rights of Indigenous peoples, for example.

The data will be independently verified, scored, aggregated and recorded on a battery passport – a digital record of the battery’s composition, which will include the origin of its raw materials and its performance against the GBA’s sustainability benchmarks.

The scheme is due to launch in 2027.

A carrot and a stick

Since the start of the year, some of the world’s largest battery companies have been voluntarily participating in the biggest pilot of the scheme to date.

More than 30 companies across the EV battery and stationary storage supply chains are involved, among them Chinese battery giants CATL and BYD subsidiary FinDreams Battery, miner Rio Tinto, battery producers Samsung SDI and Siemens, automotive supplier Denso and Tesla.

Petersen said she was “thrilled” about support for the scheme. Amid a growing pushback against sustainability rules and standards, “these companies are stepping up to send a public signal that they are still committed to a sustainable and responsible battery value chain,” she said.

There are other motivations for battery producers to know where components in their batteries have come from and whether they have been produced responsibly.

In 2023, the EU adopted a law regulating the batteries sold on its market.

From 2027, it mandates all batteries to meet environmental and safety criteria and to have a digital passport accessed via a QR code that contains information about the battery’s composition, its carbon footprint and its recycling content.

The GBA certification is not intended as a compliance instrument for the EU law but it will “add a carrot” by recognising manufacturers that go beyond meeting the bloc’s rules on nature and human rights, Petersen said.

Raising standards in complex supply chain

But challenges remain, in part due to the complexity of battery supply chains.

In the case of timber, “you have a single input material but then you have a very complex range of end products. For batteries, it’s almost the reverse,” Petersen said.

The GBA wants its certification scheme to cover all critical minerals present in batteries, covering dozens of different mining, processing and manufacturing processes and hundreds of facilities.

“One of the biggest impacts will be rewarding the leading performers through preferential access to capital, for example, with investors choosing companies that are managing their risk responsibly and transparently,” Petersen said.

It could help influence public procurement and how companies, such as EV makers, choose their suppliers, she added. End consumers will also be able to access a summary of the GBA’s scores when deciding which product to buy.

US, Europe rush to build battery supply chain

Today, the GBA has more than 150 members across the battery value chain, including more than 50 companies, of which over a dozen are Chinese firms.

China produces over three-quarters of batteries sold globally and it dominates the world’s battery recycling capacity, leaving the US and Europe scrambling to reduce their dependence on Beijing by building their own battery supply chains.

Petersen hopes the alliance’s work can help build trust in the sector amid heightened geopolitical tensions. “People want to know where the materials are coming from and which actors are involved,” she said.

At the same time, companies increasingly recognise that failing to manage sustainability risks can threaten their operations. Protests over environmental concerns have shut down mines and battery factories across the world.

“Most companies know that and that’s why they’re making these efforts,” Petersen added.

The post Battery passport plan aims to clean up the industry powering clean energy appeared first on Climate Home News.

Battery passport plan aims to clean up the industry powering clean energy

Climate Change

Reheating plastic food containers: what science says about microplastics and chemicals in ready meals

How often do you eat takeaway food? What about pre-prepared ready meals? Or maybe just microwaving some leftovers you had in the fridge? In any of these cases, there’s a pretty good chance the container was made out of plastic. Considering that they can be an extremely affordable option, are there any potential downsides we need to be aware of? We decided to investigate.

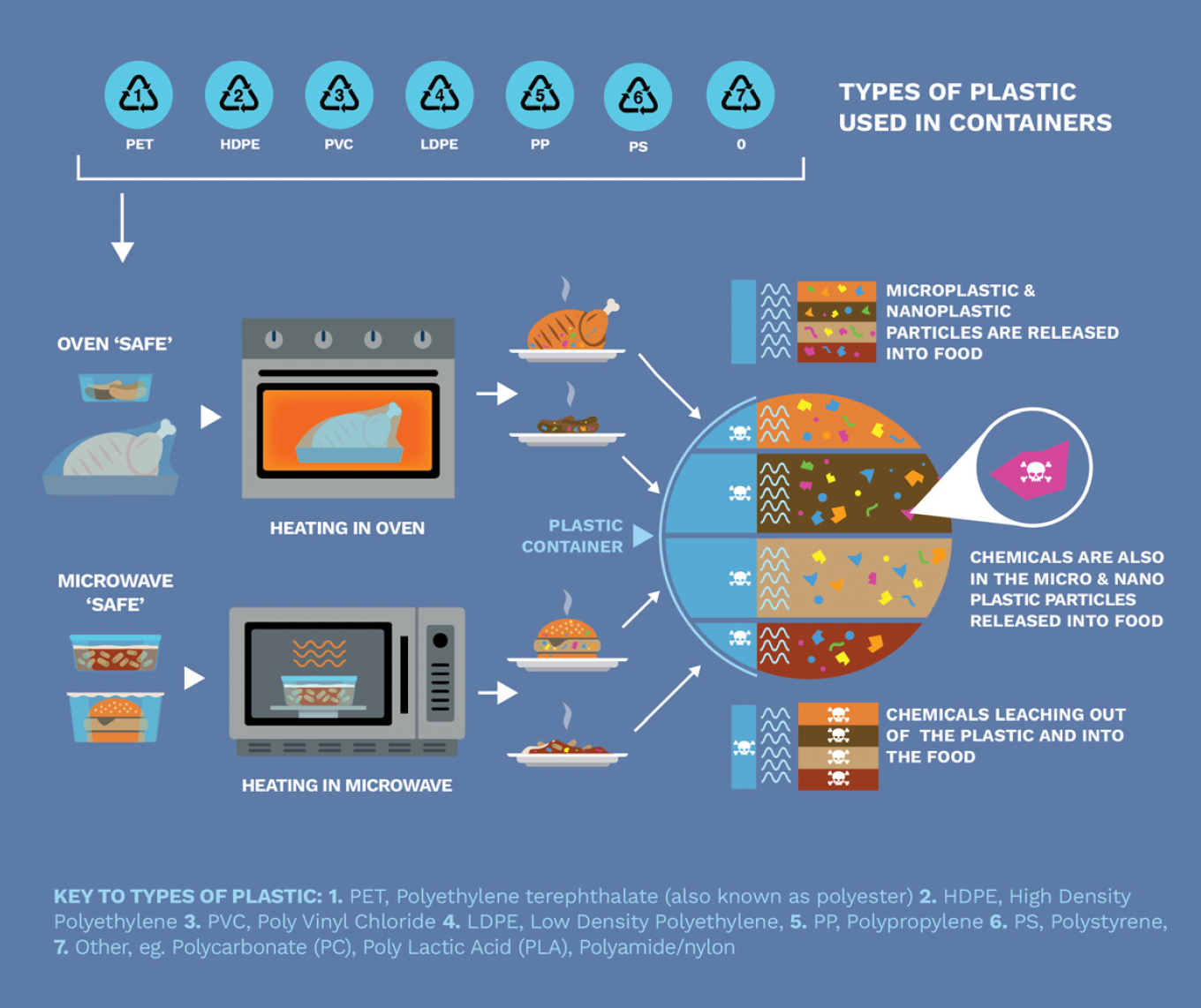

Scientific research increasingly shows that heating food in plastic packaging can release microplastics and plastic chemicals into the food we eat. A new Greenpeace International review of peer-reviewed studies finds that microwaving plastic food containers significantly increases this release, raising concerns about long-term human health impacts. This article summarises what the science says, what remains uncertain, and what needs to change.

There’s no shortage of research showing how microplastics and nanoplastics have made their way throughout the environment, from snowy mountaintops and Arctic ice, into the beetles, slugs, snails and earthworms at the bottom of the food chain. It’s a similar story with humans, with microplastics found in blood, placenta, lungs, liver and plenty of other places. On top of this, there’s some 16,000 chemicals known to be either present or used in plastic, with a bit over a quarter of those chemicals already identified as being of concern. And there are already just under 1,400 chemicals that have been found in people.

Not just food packaging, but plenty of household items either contain or are made from plastic, meaning they potentially could be a source of exposure as well. So if microplastics and chemicals are everywhere (including inside us), how are they getting there? Should we be concerned that a lot of our food is packaged in plastic?

Greenpeace analysis of 24 articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals found that the plastics we use to package our food are directly risking our health.

Heating food in plastic packaging dramatically increases the levels of microplastics and chemicals that leach into our food.

Plastic food packaging: the good, the bad, and the ugly

The growing trend towards ready meals, online shopping and restaurant delivery, and away from home-prepared meals and individual grocery shopping, is happening in every region of the world. Since the first microwaveable TV dinners were introduced in the US in the 1950s to sell off excess stock of turkey meat after Thanksgiving holidays, pre-packaged ready meals have grown hugely in sales. The global market is worth $190bn in 2025, and is expected to reach a total volume of 71.5 million tonnes by 2030. It’s also predicted that the top five global markets for convenience food (China, USA, Japan, Mexico and Russia) will remain relatively unchanged up to 2030, with the most revenue in 2019 generated by the North America region.

A new report from Greenpeace International set out to analyse articles in peer-reviewed, scientific journals to look at what exactly the research has to say about plastic food packaging and food contact plastics.

Here’s what we found.

Our review of 24 recent articles highlights a consistent picture that regulators, businesses and

consumers should be concerned about: when food is packaged in plastic and then microwaved, this significantly increases the risk of both microplastic and chemical release, and that these microplastics and chemicals will leach into the food inside the packaging.

And not just some, but a lot of microplastics and chemicals.

When polystyrene and polypropylene containers filled with water were microwaved after being stored in the fridge or freezer, one study found they released anywhere between 100,000-260,000 microplastic particles, and another found that five minutes of microwave heating could release between 326,000-534,000 particles into food.

Similarly there are a wide range of chemicals that can be and are released when plastic is heated. Across different plastic types, there are estimated to be around 16,000 different chemicals that can either be used or present in plastics, and of these around 4,200 are identified as being hazardous, whilst many others lack any form of identification (hazardous or otherwise) at all.

The research also showed that 1,396 food contact plastic chemicals have been found in humans, several of which are known to be hazardous to human health. At the same time, there are many chemicals for which no research into the long-term effects on human health exists.

Ultimately, we are left with evidence pointing towards increased release of microplastics and plastic chemicals into food from heating, the regular migration of microplastics and chemicals into food, and concerns around what long-term impacts these substances have on human health, which range from uncertain to identified harm.

The known unknowns of plastic chemicals and microplastics

The problem here (aside from the fact that plastic chemicals are routinely migrating into our food), is that often we don’t have any clear research or information on what long-term impacts these chemicals have on human health. This is true of both the chemicals deliberately used in plastic production (some of which are absolutely toxic, like antimony which is used to make PET plastic), as well as in what’s called non-intentionally added substances (NIAS).

NIAS refers to chemicals which have been found in plastic, and typically originate as impurities, reaction by-products, or can even form later when meals are heated. One study found that a UV stabiliser plastic additive reacted with potato starch when microwaved to create a previously unknown chemical compound.

We’ve been here before: lessons from tobacco, asbestos and lead

Although none of this sounds particularly great, this is not without precedence. Between what we do and don’t know, waiting for perfect evidence is costly both economically and in terms of human health. With tobacco, asbestos, and lead, a similar story to what we’re seeing now has played out before. After initial evidence suggesting problems and toxicity, lobbyists from these industries pushed back to sow doubt about the scientific validity of the findings, delaying meaningful action. And all the while, between 1950-2000, tobacco alone led to the deaths of around 60 million people. Whilst distinguishing between correlation and causation, and finding proper evidence is certainly important, it’s also important to take preventative action early, rather than wait for more people to be hurt in order to definitively prove the point.

Where to from here?

This is where adopting the precautionary principle comes in. This means shifting the burden of proof away from consumers and everyone else to prove that a product is definitely harmful (e.g. it’s definitely this particular plastic that caused this particular problem), and onto the manufacturer to prove that their product is definitely safe. This is not a new idea, and plenty of examples of this exist already, such as the EU’s REACH regulation, which is centred around the idea of “no data, no market” – manufacturers are obligated to provide data demonstrating the safety of their product in order to be sold.

Greenpeace analysis of 24 articles in peer-reviewed scientific journals found that the plastics we use to package our food are directly risking our health.

Heating food in plastic packaging dramatically increases the levels of microplastics and chemicals that leach into our food.

But as it stands currently, the precautionary principle isn’t applied to plastics. For REACH in particular, plastics are assessed on a risk-based approach, which means that, as the plastic industry itself has pointed out, something can be identified as being extremely hazardous, but is still allowed to be used in production if the leached chemical stays below “safe” levels, despite that for some chemicals a “safe” low dose is either undefined, unknown, or doesn’t exist.

A better path forward

Governments aren’t acting fast enough to reduce our exposure and protect our health. There’s no shortage of things we can do to improve this situation. The most critical one is to make and consume less plastic. This is a global problem that requires a strong Global Plastics Treaty that reduces global plastic production by at least 75% by 2040 and eliminates harmful plastics and chemicals. And it’s time that corporations take this growing threat to their customers’ health seriously, starting with their food packaging and food contact products. Here are a number of specific actions policymakers and companies can take, and helpful hints for consumers.

Policymakers & companies

- Implement the precautionary principle:

- For policymakers – Stop the use of hazardous plastics and chemicals, on the basis of their intrinsic risk, rather than an assessment of “safe” levels of exposure.

- For companies – Commit to ensure that there is a “zero release” of microplastics and hazardous chemicals from packaging into food, alongside an Action Plan with milestones to achieve this by 2035

- Stop giving false assurances to consumers about “microwave safe” containers

- Stop the use of single-use and plastic packaging, and implement policies and incentives to foster the uptake of reuse systems and non-toxic packaging alternatives.

Consumers

- Encourage your local supermarkets and shops to shift away from plastic where possible

- Avoid using plastic containers when heating/reheating food

- Use non-plastic refill containers

Trying to dodge plastic can be exhausting. If you’re feeling overwhelmed, you’re not alone. We can only do so much in this broken plastic-obsessed system. Plastic producers and polluters need to be held accountable, and governments need to act faster to protect the health of people and the planet. We urgently need global governments to accelerate a justice-centred transition to a healthier, reuse-based, zero-waste future. Ensure your government doesn’t waste this once-in-a-generation opportunity to end the age of plastic.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits