From canola farmers in Canada to car owners in India, biofuels have become the subject of everyday debate across the world.

Liquid biofuels feature heavily in the climate plans of many countries, as governments prioritise domestic energy security amid geopolitical challenges, while looking to meet their climate targets and bolster farm incomes.

Despite a rapid shift towards electrified transportation, biofuels continue to play a leading role in efforts to reduce road-transport emissions, as they work well with many existing car engines.

At the same time, biofuels are expected to play an important role in decarbonising sectors where emissions are particularly challenging to mitigate, such as shipping, trucking and aviation.

Heated debates continue around using food sources as fuel in the face of record hunger levels, given competing demands for land and crops.

Despite these arguments, biofuels are seeing heightened demand bolstered by a strong policy push, particularly in developing countries.

They are expected to feature heavily on the COP30 agenda this year as a key feature of the host Brazil’s “bioeconomy”.

Below, Carbon Brief unpacks what biofuels are, their key benefits and criticisms, plus how they are being used to meet climate targets.

- What are biofuels?

- What are the most common biofuels being used today?

- What are the main arguments for biofuels?

- What are some of the main criticisms of biofuels?

- How are countries using biofuels to meet their climate targets?

- How could climate change impact biofuel production?

What are biofuels?

Bioenergy refers to all energy derived from biomass, a term used to describe non-fossil material from biological sources. Biofuels, in turn, are liquid fuels that are produced from biomass.

These sources are wide-ranging, but commonly include food crops, vegetable oils, animal fats, algae and municipal or agricultural waste, along with synthetic derivatives from these products.

Glossary

Biomass

Non-fossil material of biological origin

Biofuel

Fuels produced directly or indirectly from biomass

Feedstock

Types of biomass used as sources for biofuels, such as crops, grasses, agricultural and forestry residues, wastes and microbial biomass

Bioenergy

All energy derived from biofuels

Bioethanol

A biofuel used as a petrol substitute, produced from the fermentation of biomass from plants like corn, sugarcane and wheat

Biodiesel

A biofuel used as a diesel substitute, derived from vegetable oils or animal fats through a process called transesterification

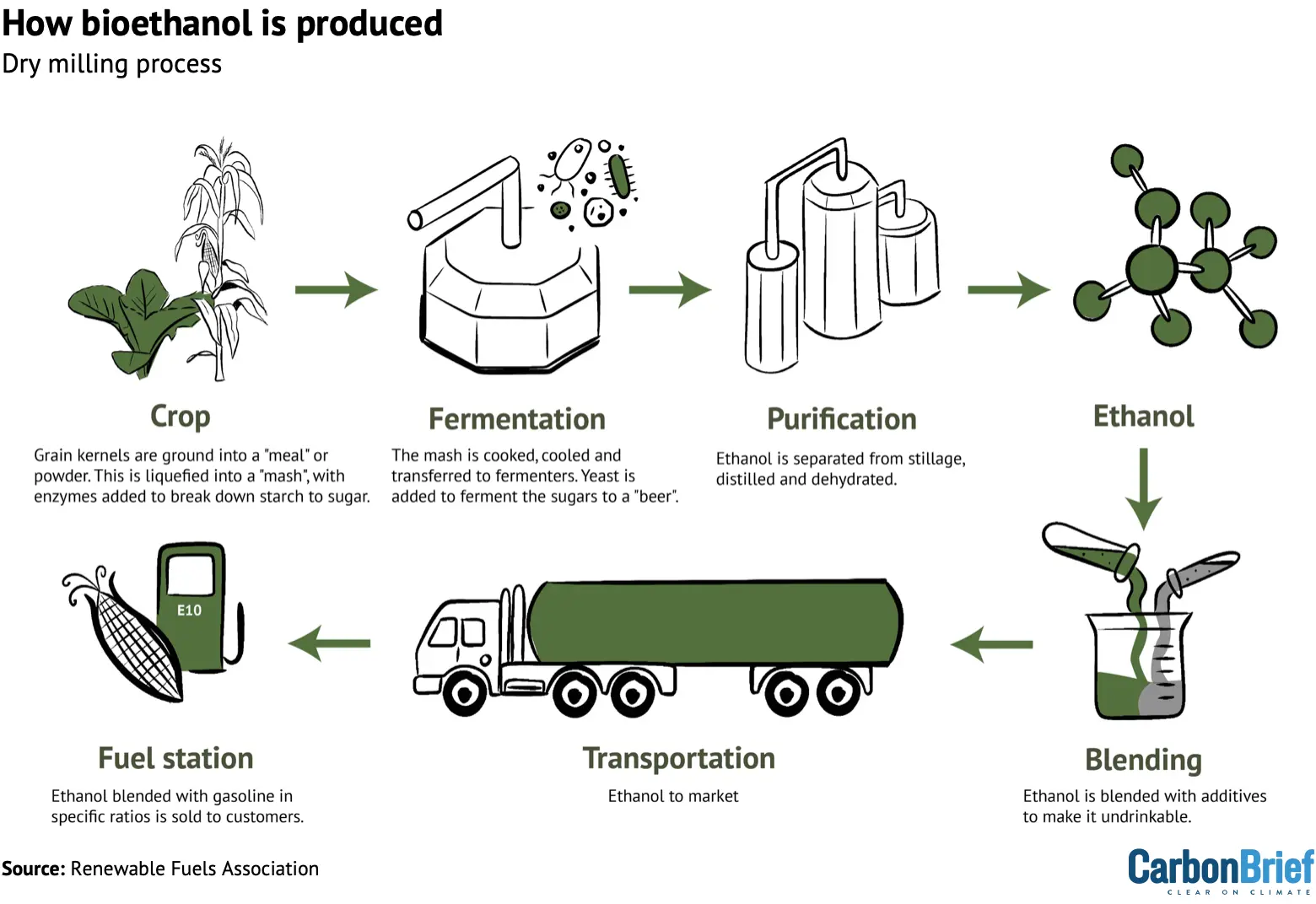

The different types of biomass are referred to as “feedstocks”. They are converted to fuel through one or more processes, such as fermentation or treating them with high temperatures or hydrogen.

Biofuels are frequently blended with petroleum products in an effort to reduce emissions and reliance on fossil-fuel imports.

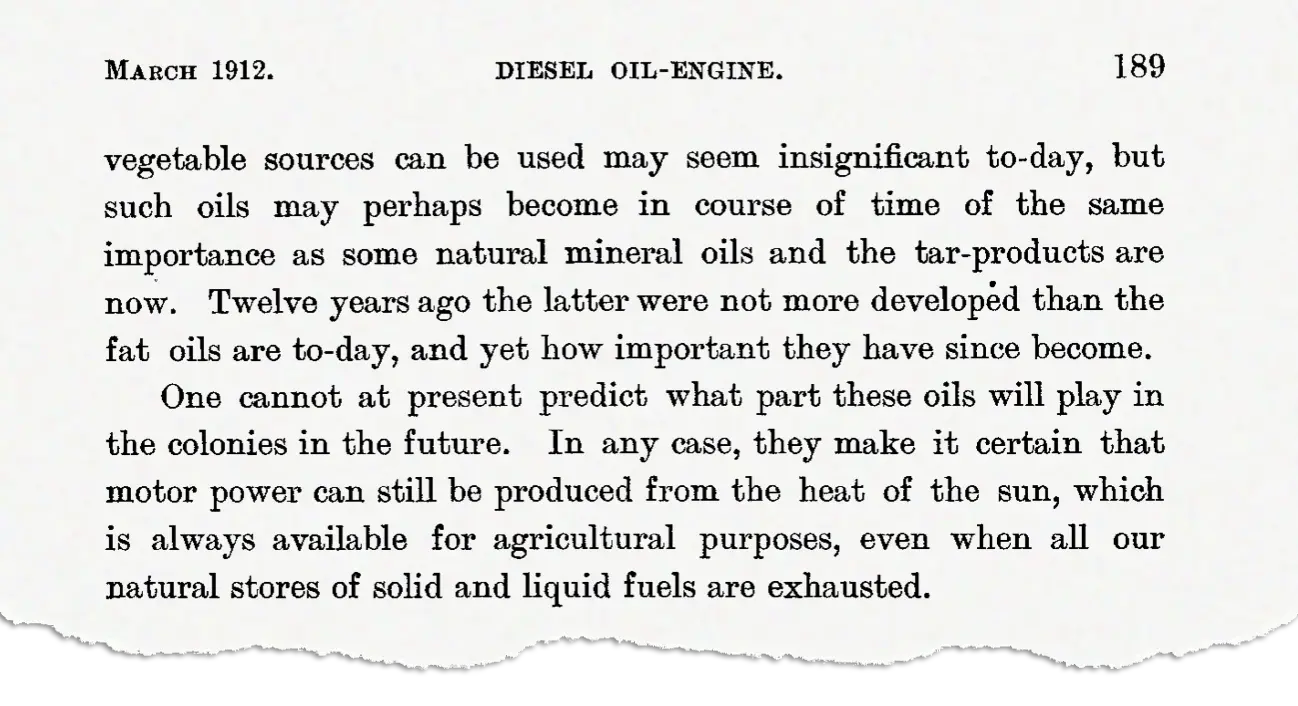

Experiments to test whether vegetable oils could run in combustion engines began in the early 1900s. In a 1912 paper, Rudolf Diesel – the inventor of the diesel engine – presciently noted that these oils “make it certain that motorpower can still be produced from the heat of the sun…even when all our natural stores of solid and liquid fuels are exhausted”.

An extract from Rudolf Diesel’s 1912 paper, published in the Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers, outlining the importance biofuels could assume in the future. Credit: Proceedings of the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (1912)

Biofuels are divided into four “generations”, based on the technologies and feedstocks used to synthesise them.

| Type of biofuel | Source |

| First-generation | Food crops (eg, sugarcane, corn, wheat, rice) |

| Second-generation | Non-edible crops and materials (eg, straw, grasses, used vegetable oil, forest residues, waste) |

| Third-generation | Aquatic materials (eg, algae) |

| Fourth-generation | Genetically modified algae, bacteria and yeast, as well as electrofuels, synthetic fuels and e-fuels |

First-generation biofuels

The first – and earliest – generation of biofuels comes from edible crops, such as corn, sugarcane, soya bean and oil palm. Large-scale commercial production of these fuels began in the 1970s in Brazil and the US from sugarcane and corn, respectively.

Bioethanol, for instance, is drawn from the fermentation of sugars in corn, sugarcane and rice. Biodiesel is derived from vegetable oils – such as palm, canola or soya bean oil – or animal fats, through a process called transesterification, which makes them less viscous and more suitable as fuels.

Because they are derived directly from food crops, experts and campaigners have expressed concerns over the impacts of first-generation biofuels on forests, food security and the environment, as well as indirect land-use change impacts. (See: What are some of the main criticisms of biofuels?)

Several studies have found that the land-use emissions of first-generation biofuels are severely underestimated, but other experts tell Carbon Brief that this depends on how and where the crops are grown, processed and transported.

According to Dr Angelo Gurgel, principal research scientist at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) Center for Sustainability Science and Strategy, the “big image that biofuels are bad” is not always accurate. Gurgel explains:

“Some biofuels can be better than others, varying from place to place and feedstock to feedstock. It depends on where you produce them, how much farmers can increase yields, how effectively a country’s regulations help avoid land-use change and how closely it is connected to international markets.

“Some options may be very, very good in terms of reducing emissions and other options probably will be very bad.”

Second-generation biofuels

Second-generation biofuels are extracted from biomass that is not meant for human consumption.

Feedstocks for these biofuels are incredibly varied. They include agricultural waste, such as straw and corn stalks, grasses, forest residues left over from wood processing, used vegetable oil and solid waste. They can also be made from energy crops grown specifically to serve as biofuels, such as jatropha, switchgrass or pongamia.

Derived from “waste” or grown on “marginal” land, second-generation biofuels were developed in the early 2000s. These fuels aimed to overcome the food security and land-use issues tied to their predecessors, while increasing the amount of fuel drawn out from biomass, compared to first-generation feedstocks.

These feedstocks are either heated to yield oil or “syngas” and then cooled, or treated with enzymes, microorganisms or other chemicals to break down the tough cellulose walls of plants. They can be challenging to process and present significant logistical and land-use challenges.

Third-generation biofuels

Third-generation biofuels are primarily derived from aquatic organic material, particularly algae and seaweed. While the US Department of Energy began its aquatic species programme in 1978 to research the production of biodiesel from algae, algal biofuel research saw a “sudden surge” in the 1990s and “became the darling” of renewable energy innovation in the early 21st century, says Mongabay.

Because algae grows faster than terrestrial plants, is high in lipid (fatty organic) content and does not compete with terrestrial crops for land use, many scientists and industry professionals consider third-generation biofuels an improvement over their predecessors.

However, high energy, water and nutrient needs, high production costs and technical challenges are key obstacles to the large-scale production of algae-based biofuels. Since the early 2010s, many companies, including Shell, Chevron, BP and ExxonMobil, have abandoned or cut funding to their algal biofuel development programmes.

Fourth-generation biofuels

Genetically modified algae, bacteria and yeast engineered for higher yields serve as the feedstock for fourth-generation biofuels. These fuels have been developed more recently – from the early 2010s onwards – and are an area of ongoing research and development.

Some of these organisms are engineered to directly or artificially photosynthesise solar energy and carbon dioxide (CO2) into fuel; these are called solar biofuels.

Others – called electrofuels, synthetic fuels or e-fuels – are produced when CO2 captured from biomass is combined with hydrogen and converted into hydrocarbons through other processes, typically using electricity generated from renewable sources.

Fourth-generation biofuels are technology- and CO2-intensive and expensive to produce. They also run up against public perception and legal limitations on genetically modified organisms, as well as concerns around biosafety and health.

What are the most common biofuels being used today?

Bioethanol is the most commonly used liquid biofuel in the world, followed by biodiesel.

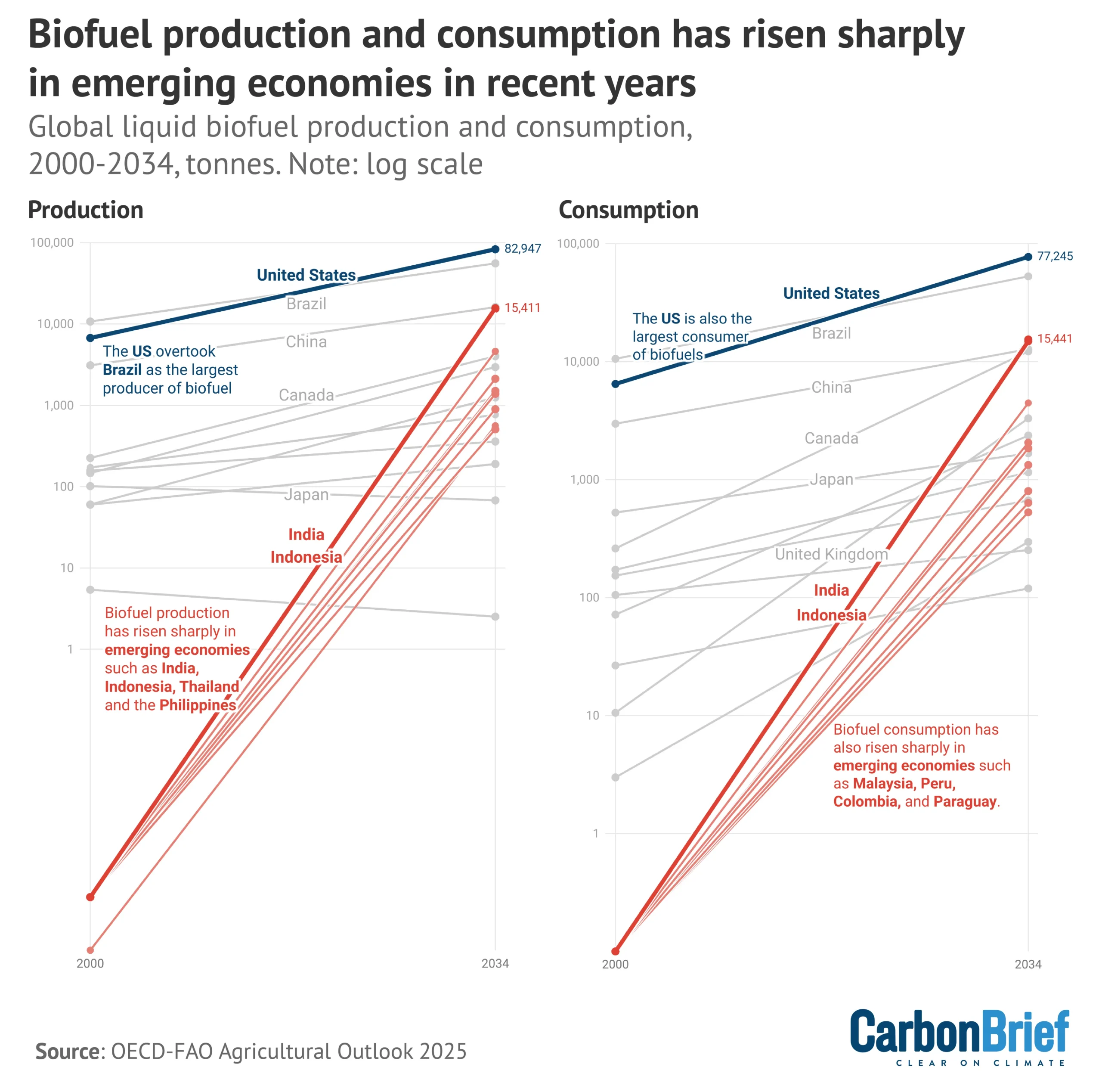

In 2024, global liquid biofuel production increased by 8% year-on-year, with the US (37%) and Brazil (22%) accounting for the largest overall share of production, according to the 2025 Statistical Review of World Energy from the Energy Institute.

Other countries that saw a notable increase in production between 2023-24 were Sweden (62%), Canada (39%), China (30%), India (26%) and Argentina (24%).

Bioethanol is the most commonly used biofuel in the world, with a consumption rate of 1.1m barrels of oil equivalent per day in 2024, according to the report. This is closely followed by biodiesel, at 1m barrels of oil equivalent per day.

In 2024, the US, Brazil and the EU accounted for nearly three-quarters of all biofuels consumed globally. However, while India’s biofuel demand grew by 38%, demand for biofuels in the EU fell by 11% in 2024, according to the review, echoing outlooks that show that middle-income countries are driving biofuel growth.

The chart below shows how biofuel production and consumption have changed since 2000, and how they are projected to change through 2034.

What are the main arguments for biofuels?

From lowered oil imports and emissions through to boosting farm livelihoods, countries that have boosted biofuels programmes cite several benefits in biofuels’ favour.

‘Renewable’ energy and lowered emissions

Biofuels are often described as “renewable” fuels, since crops can be grown over and over again.

In order to achieve this, crops for biofuels must be continuously replanted and harvested to meet energy demand. Growing crops – particularly in the monoculture plantations typically used for growing feedstocks – can require high use of fossil fuels, in the form of machinery and fertiliser. Furthermore, in the case of wood as a feedstock, regrowth can take decades.

While some biofuels offer significant emissions reductions, others, such as palm biodiesel, generate similar or sometimes higher emissions as fossil fuels when burned. However, ancillary emissions for biofuels are much smaller than for oil and gas operations.

One of the main cited benefits of biofuels is that plants capture CO2 from the atmosphere as they grow, potentially serving to mitigate emissions. However, several lifecycle-assessment studies have questioned just how much plants can offset emissions. These studies come up with varying estimates based on feedstock types, geography, production routes and methodology.

This divergence is echoed in the UN Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC) Sixth Assessment Report (AR6), which points to “contrasting conclusions” even when similar bioenergy systems and conditions are analysed.

Per the report, there is “medium agreement” on the emissions-reduction potential of second-generation biofuels derived from wastes and residues by 2050.

At the same time, the IPCC adds that “technical land availability does not imply that dedicated biomass production for bioenergy…is the most effective use of this land for mitigation”.

It also warns that larger-scale biofuel use “generally translates into higher risk for negative outcomes for greenhouse gas emissions, biodiversity, food security and a range of other sustainability criteria”.

Along with the IPCC, many other groups and experts – including the UK’s Climate Change Commission – have called for a “biomass hierarchy”, pointing to a limited amount of sustainable bioenergy resources available and how best to prioritise their use.

Use in hard-to-abate sectors

In many countries, such as the US and UK, biofuels are part of a standard grade of diesel and petrol (gasoline) available at most fuel pumps.

Biofuels have also been the leading measure for decarbonising road transport in emerging economies, where electric vehicle systems were not as developed as in many western nations.

According to the International Energy Agency (IEA), most new biofuel demand is coming from these countries, including Brazil, India and Indonesia.

Biofuels are also one of the key options being explored to decarbonise the emissions-heavy, but “hard-to-abate”, sectors of aviation and shipping.

The AR6 report notes that the “faster-than-anticipated adoption of electromobility” has “partially shifted the debate” from using biofuels primarily in land transport towards using them in shipping and aviation.

At the same time, experts question how this can be done sustainably, given the limited availability of advanced biofuels and the rising demand for them.

Government reports – such as those released by the EU Commission – recognise that, in some circumstances, so-called sustainable aviation fuels (SAFs) could produce just as many emissions as fossil fuels when burned in order to power planes.

However, SAFs do generally – although not always – have a lower overall “lifecycle” carbon footprint than petroleum-based jet fuel. This is due to the CO2 absorbed when growing plants for biofuels, or emissions that are avoided by diverting waste products to be used as fuels.

Unlike the road sector, where “electrification is mature…aviation and shipping cannot be electrified so easily”, says Cian Delaney, fuels policy officer at the Brussels-based advocacy group Transport & Environment (T&E).

According to a 2025 T&E briefing, the 2030 demand for biofuels from global shipping alone could require an area the “size of Germany”. Delaney tells Carbon Brief:

“In aviation in particular, where you still need some space to transition, you still need a certain amount of biofuels. But these biofuels should be advanced and waste biofuels derived from true waste and residues, and they are available in truly limited amounts, which is why, in parallel, we need to upscale the production of e-fuels [synthetic fuels derived from green hydrogen] for aviation.”

In February this year, more than 65 environmental organisations from countries including the US, Indonesia and the Netherlands wrote to the International Maritime Organization, urging its 176 member states to “exclude biofuels from the industry’s energy mix”.

The organisations cited the “devastating impacts on climate, communities, forests and other ecosystems” from biofuels, cautioning that fuels such as virgin palm oil are often “fraud[ulently]” mislabelled as used cooking oil – a key feedstock for SAF.

Meanwhile, the AR6 report has “medium confidence” that heavy-duty trucks can be decarbonised through a combination of batteries and hydrogen or biofuels. And despite growing interest in the use of biofuels for aviation, it says, “demand and production volumes remain negligible compared to conventional fossil aviation fuels”.

Energy security and reducing import dependence

In many countries, such as India and Indonesia, biofuels are seen as a part of a suite of measures to increase energy security and lessen dependence on fossil-fuel imports from other countries. This imperative received increasing emphasis after the Covid-19 pandemic and Russia’s war on Ukraine.

In developing countries, the “main motivation” behind biofuel policy is to find an alternative to excessive dependence on imported fossil fuels that are a “major drain” on foreign exchanges and subject to volatility and price shocks, says Prof Nandula Raghuram, professor of biotechnology at the Guru Gobind Singh University in New Delhi.

Raghuram, who formerly chaired the International Nitrogen Initiative, tells Carbon Brief that, in order for developing countries to “earn those precious dollars to finance our petroleum imports”, they have to export “valuable primary commodities”, such as grain and vegetables, at the cost of nutritional self-reliance. He adds:

“And so we have to see the biofuel approach as not so much a proactive strategy, but as a sort of reactive strategy to use whatever domestic capacity we have to produce whatever domestic fuel, including biofuels, to reduce that much burden on the exchequer for imports.”

Boost to agriculture

Many governments also see biofuels as an alternative income stream for farmers and a means to revitalise rural economies.

An increasing demand for biofuels could, for example, offer farmers higher returns on their crops, attract industry and services to agrarian areas and help diversify farm incomes.

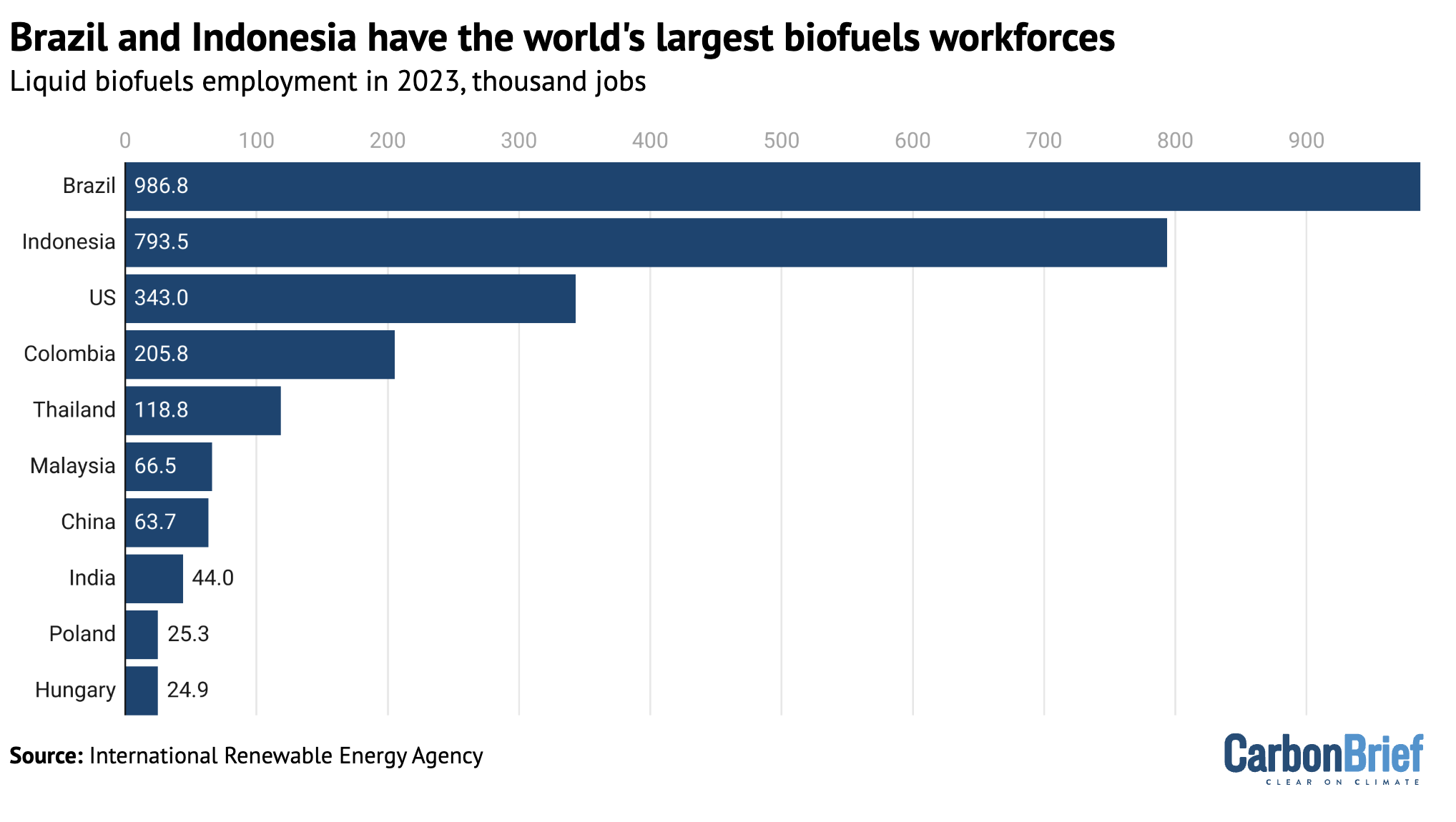

In 2023, a report by the International Labour Organization (ILO) and the International Renewable Energy Agency (IRENA) estimated that the liquid biofuel industry employed approximately 2.8 million people worldwide.

The bulk of these jobs were in Latin America and Asia, where farming is more labour-intensive and relies on informal and seasonal employment. Brazil’s biofuel sector alone employed nearly one million people in 2023, according to the report.

Meanwhile, North America and Europe accounted for only 12% and 6% of biofuel jobs in 2023, respectively, according to the report.

The chart below shows the number of jobs in the biofuel sector in the top 10 biofuel-producing countries.

Delaney points out that biofuel-related jobs account for less than 1% of all jobs in the EU, adding that the “most-consumed biofuel feedstocks” in the bloc are vegetable oils that are imported from countries such as Brazil and Indonesia. (See: How are countries using biofuels to meet their climate targets?)

He tells Carbon Brief:

“Despite strong biofuels mandates in the EU, the sector didn’t create as many jobs in the end for EU farmers, but, instead, benefited the big fuel suppliers and industry players.”

What are some of the main criticisms of biofuels?

Despite their widespread use and increasing adoption, experts recognise that biofuels “may also carry significant risks” and cause impacts that can undermine their sustainability, if not managed carefully.

Production emissions, land-use change and deforestation

The different chemical processes involved in making biofuels require varying amounts of energy and, therefore, the associated emissions depend on how “clean” a producer country’s energy mix is.

At the same time, growing biofuel crops often relies on emissions-intensive fertilisers and pesticides to keep yields high and consistent. (See Carbon Brief’s detailed explainer on what the world’s reliance on fertilisers means for climate change.)

Biofuel production processes, such as fermentation, also release CO2 and other greenhouse gases, including methane and nitrous oxide.

MIT’s Gurgel tells Carbon Brief that it is “relatively straightforward” to measure these direct emissions from biofuel production.

However, given how different countries account for deforestation, tracking direct land-use change emissions related to biofuel production is slightly more challenging – although still possible, Gurgel says. These emissions can come from clearing forests or converting other land specifically for growing energy crops.

For example, in many tropical forest countries, native rainforests and peatland have been cleared to grow oil palm for biodiesel or sugarcane for bioethanol.

According to one 2011 study by the Centre for International Forestry Research and World Agroforestry (CIFOR-ICRAF), it could take more than 200 years to reverse the carbon emissions caused by clearing peatland to grow palm oil.

Gurgel tells Carbon Brief:

“What is really very hard – I would say impossible – to measure are the indirect impacts of biofuels on land.”

Indirect land-use change occurs when a piece of land used to grow food crops is used instead for biofuels. This can, in turn, require deforestation somewhere else to produce the same amount of crops for food as the original piece of land.

Indirect land-use change can mean a loss of natural ecosystems, with “significant implications for greenhouse gas emissions and land degradation”, according to a 2024 review paper.

Gurgel explains:

“If you provoke a chain of reactions in the market, that can lead to expansion of cropland in another region of the world and then this can push the agricultural frontier further and cause some deforestation…It’s quite hard to know exactly what’s going to happen and those things are interactions in the market that are impossible to measure.”

The “best that scientists can do” to determine if such a “biofuel shock” could indeed cause land-use change in a forest or grassland elsewhere “is try to project those emissions using models, or do very careful statistical work that will never be complete”, he adds.

Delaney, from Transport and Environment, contends that there is enough scientific research to “show that indirect land-use change is real” and to quantify the expansion of “certain food and feedstocks into high-carbon stock” areas, such as forests.

While this is “not easy” to do, he points to the European Commission’s indirect land-use change directive, the accompanying methodology and its scientific teams who study agricultural expansion rates. Delaney continues:

“What we all agree with at this point is that indirect land-use change exists, that it’s a problem, that certain feedstocks like palm and soya are particularly problematic from this perspective and that it is an issue that we need to tackle and capture in the best possible way.

“You cannot just be vague and descriptive without having proper figures behind it – and I think that’s something that at least the EU have tried and that they continue trying to implement. And I hope that, at the global level as well, this will be more recognised.”

Impacts on food, biodiversity and water security

Biofuel-boosting policies have been subjected to intense scrutiny during periods of global food-price spikes in 2008, 2011 and 2013.

Following the spikes, critics attributed increasing biofuel production as a major factor in the near-doubling of cereal prices. Studies have shown that they played a more “modest” role in some of these spikes and a more substantial one in others.

Severalexperts have linked food-price spikes to protests in north Africa and the Middle-East, including the Arab Spring.

In more recent years, the “food vs fuel debate” has come back to the fore since the start of the war in Ukraine in 2022.

This was in part due to the world’s reliance on Ukraine and Russia’s food and energy systems – particularly some of the most food-insecure countries, who had to contend with record-high food prices that peaked in March 2022, but still persist. The war also saw heightened calls for the US and EU to overturn biofuel-boosting policies to free up land to increase domestic food production and bring down food prices.

In developing countries, such as India, the use of cereals and oils to make biofuels while large sections of the population still lack access to adequate nutrition has attracted criticism from experts.

While first-generation biofuels rely on fertilisers to guarantee consistently high yields, second-generation biofuels could directly compete with feed for livestock or their return to soil as nutrients.

According to a 2013 report by the panel of scientists that advises the UN Committee on World Food Security (CFS):

“All crops compete for the same land or water, labour, capital, inputs and investment, and there are no current magic non-food crops that can ensure more harmonious biofuel production on marginal lands.”

This competition, along with clearing forests and other ecosystems for cropland, has consequences not just for emissions, but also for biodiversity, water and nutrients.

According to one 2021 review paper, local species richness and abundance were 37% and 49% lower, respectively, in places where first-generation biofuel crops were being grown than in places with primary vegetation. Additionally, it found that soya, wheat, maize and palm oil had the “worst effects” on local biodiversity, with Asia and central and South America being the most-impacted regions.

Biofuels’ impact on water resources, similarly, is highly crop- and location-specific.

For instance, growing a “thirsty” crop such as sugarcane in Brazil could have minimal impacts on local water resources, due to the region’s abundant rainfall. But in drought-prone India, experts have estimated that a litre of sugarcane ethanol requires more than 2,500 litres of water to produce and relies entirely on irrigation. Research has also found that nearly half of China’s maize crop requires irrigation to grow.

According to agricultural economist Dr Shweta Saini, meeting India’s 2025-26 biofuels target will require 275m tonnes of sugarcane, 6m tonnes of maize and 5.5m tonnes of rice. According to one 2020 study cited by Bloomberg columnist David Fickling, increasing sugarcane production to meet India’s biofuel targets “could consume an additional 348bn cubic metres of water…around twice what is used by every city” in the country.

Prof Raghuram tells Carbon Brief:

“Water resources are drying up everywhere in the country and by incentivising, through policy, a water-guzzling industry like this, we are inviting a sustainability crisis.”

‘Feedstock crunch’

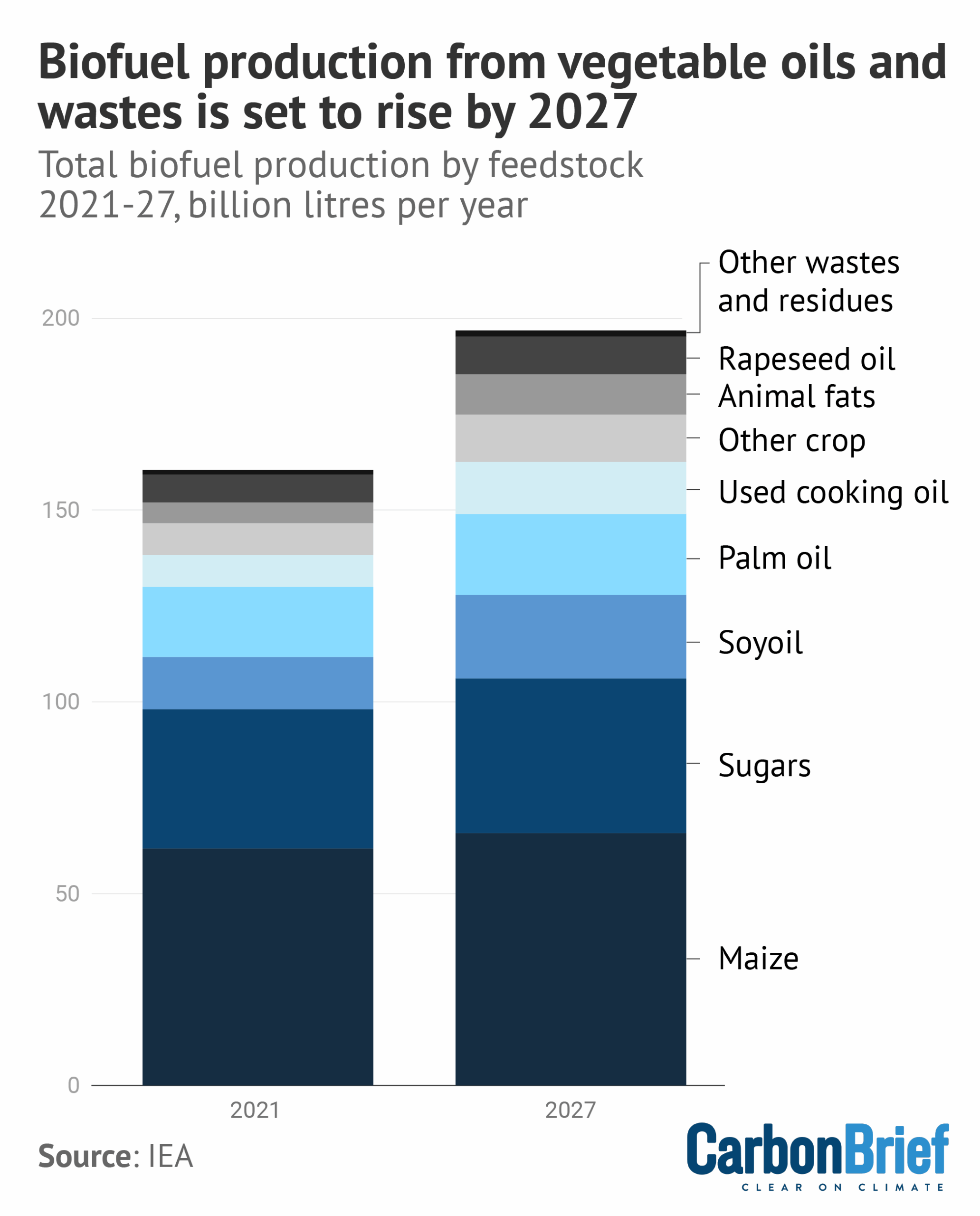

Another concern surrounding biofuels is that there may not be enough supply to go around to meet rising demand. The IEA described the potential shortfall as a “feedstock supply crunch” in a 2022 report.

Fuels derived from the most commonly used waste and residues, in particular, could be approaching supply limits, the IEA warns, as these fuels satisfy both sustainability and feedstock policy objectives in the US and EU.

Consumption of vegetable oil for biofuel production is expected to soar by 46% over 2022-27, the report says. Meanwhile, the world is estimated to “nearly exhaust 100% of supplies” of used cooking oil and animal fats within the decade.

For the world to stay on a net-zero trajectory, “a more than three times production increase” would be required, the report adds. It warns that if the limited availability of second-generation feedstocks continues unchanged, “the potential for biofuels to contribute to global decarbonisation efforts could be undermined”.

The chart below shows the biofuel demand share of global crop production from 2022-27.

How are countries using biofuels to meet their climate targets?

Broadly, biofuel policies are divided into two categories.

Technology “push” policies focus on the research and development of new technologies and include measures such as research funding, pilot plants and government support for commercialising nascent technologies.

Meanwhile, market “pull” policies drive demand for existing and emerging biofuels through measures such as “biofuel blending mandates” – where countries prescribe a certain percentage of biofuel with fossil fuels – and tax breaks for producers and vehicle owners.

US

The US Renewable Fuel Standard (RFS) is the world’s largest existing biofuel programme. Its mandates are keenly watched and contested by the country’s farm and petroleum lobbies.

Under RFS, the US Environmental Protection Agency sets out minimum levels of biofuels that must be blended into the US’s transport, heating and jet fuel supplies.

Under the policy, oil refiners can either blend mandated volumes of biofuels into the nation’s fuel supply or buy credits – called Renewable Identification Numbers (RINS) – from those that do.

While the programme sets out emissions reduction targets, the environmental impacts of cropland expansion and monoculture driven by the policy have been cause for concern by experts.

According to one 2022 study, the RFS programme increased US fertiliser use by 3-8% each year between 2008-16 and caused enough domestic emissions from land-use change that the carbon intensity of corn ethanol was “no less than that of gasoline and likely at least 24% higher”. Additionally, the programme’s impacts on biodiversity have not yet been fully assessed.

In June 2025, the Trump administration announced plans to expand the biofuel mandate to a “record 24.02bn gallons” next year – an 8% increase from its 2025 target – while seeking to discourage imported biofuels.

EU

In the EU, policymakers have promoted biofuels since 2003 to reduce emissions in the transport system. As part of the EU’s Renewable Energy Directive (RED), biofuels have been explicitly linked to emissions targets.

Under the current iteration of RED (REDIII) – revised as part of the EU’s Fit for 55 package – EU countries are required to either achieve a share of 29% of renewable energy in transport or to reduce the emissions intensity of transport fuels by 14.5%. Additionally, it sets out a sub-target for “advanced biofuels” of 5.5% and excludes the use of food and feed-based biofuels in aviation and shipping.

In 2015, the European Commission acknowledged that the indirect land-use change emissions of first-generation biofuels could “fully negate” any emission savings by biofuels. The commission capped the use of first-generation biofuels in each member country at 7% of all energy used in transport by 2020, but did not announce plans to phase them out.

As of 2021, nearly 60% of all biofuels used in the EU were still made from food and feed crops, according to analysis by Oxfam. While the latest RED legislation continues to push for the use of advanced and waste biofuels, campaigners warn that a lack of clear definitions could increase the risk of “loopholes” and fraud, exacerbated by increased demand.

T&E’s Delaney tells Carbon Brief:

“You’re putting a lot of pressure on the land – you might require a lot of pesticides and irrigation – and there is not even enough land in Europe for this. How can you make sure true sustainability safeguards are in place so that you’re not actually driving additional demand for land in [biodiverse countries such as] Brazil?”

Brazil

Brazil has the world’s oldest biofuels mandate, dating back to the 1970s, established in a bid to insulate the country from expensive oil imports.

In 2017, Brazil announced a state policy called RenovaBio that set out national carbon intensity reduction targets for transport, decided biofuel mandates and created an open market for biofuel decarbonisation carbon reduction credits called CBIO.

In October 2024, Brazil enacted a “Fuels of the Future” law that replaced RenovaBio, with president Lula declaring that “Brazil will lead the world’s largest energy revolution”. The law aims to boost biofuel and sustainable aviation fuel (SAF) use, increasing biodiesel blending mandates by 1% every year starting in 2025 until it reaches 20% by March 2030.

Biofuels now account for 22% of the energy that fuels transport in Brazil and its ethanol market is “second in size only” to the US.

In June this year, Brazil announced that the country was increasing its biofuel blending mandates from 1 August in a bid to make the country “gasoline self-sufficient for the first time in 15 years”, reported Reuters.

Indonesia

As the world’s biggest palm oil producer, Indonesia has continued to raise its biodiesel blending mandates to meet its domestic energy needs.

The country first introduced mandatory biodiesel blending in 2008, at 2.5%. The mandate is currently at 40% in 2025 and, starting next year, could go up to 50% with an eventual goal of 100%.

While Indonesia’s president Prabowo Subianto has stated that implementing 50% blending could save the country $20bn in reduced diesel imports, the move would need an estimated 2.3m hectares of land, including protected forests, resulting in the “country’s largest-ever deforestation project”, according to Mongabay.

It could also compete with palm oil meant for domestic and international food markets, impacting already soaring prices and signalling the “end of cheap palm oil”.

India

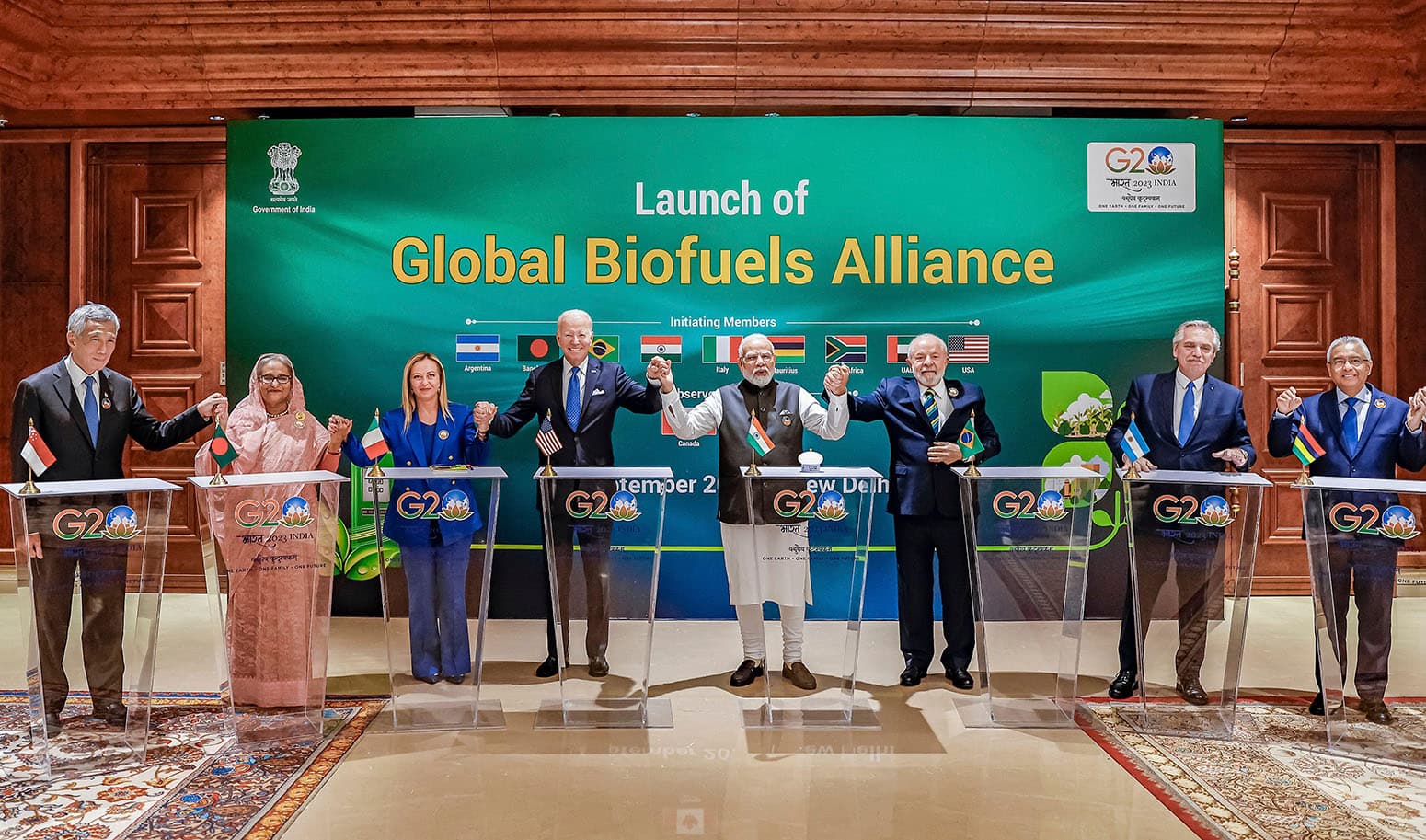

India has quickly joined the ranks of major biofuel producers, due to high-level political support, policies and a diversity of feedstocks. In 2023, India launched the Global Biofuels Alliance as one of its key priorities of its G20 presidency.

Biofuel mandates are outlined in the country’s National Policy on Biofuels, first published in 2009 and subsequently amended in 2018 and 2022. In 2022, India achieved its 10% ethanol blending target ahead of schedule and is pursuing a 20% blending target by 2025, as well as a 5% biodiesel blending target by 2030.

India’s rapid biofuel push, however, has been criticised by food security experts as hunger levels rise, for its impact on endemic rainforests and, most recently, by vehicle owners for the impact of blended fuel on car engines.

Prof Raghuram says:

“From a sheer governance angle and sustainability angle, there are a lot of compromises being made to somehow push this whole thing. Even the land available in India is shrinking, as various reforms and dilution of environmental safeguards in the last 10 years have made it relatively easier to convert farm and forest land for non-agricultural purposes.”

China

China developed its first biofuel policies over 20 years ago and is one of the world’s biggest biofuel producers.

In 2017, China announced a new mandate expanding the use of fuel including bioethanol from 11 trial provinces to the entire country by 2020. However, Reuters and South China Morning Post reported that this was suspended in 2020. Only 15 provinces still maintain biofuel mandates, according to the US Department of Agriculture, which notes that a “lack of meaningful support for domestic biofuel consumption while aggressively promoting electric vehicles indicates a strategic choice to pursue transportation decarbonisation through electrification rather than liquid biofuels”.

At the same time, biofuel production in China grew by 30% in 2024, according to the Energy Institute’s Statistical Review.

While most of China’s biofuel production is grain-based, tax incentives for ethanol production have been gradually phased out and alternative biofuels have been incentivised, according to the IEA. China is currently piloting a scheme to increase biodiesel consumption at home, even as it exports biodiesel and used cooking oil to the EU and US.

How could climate change impact biofuel production?

Despite the well-documented impacts of climate change-induced extreme weather on land, agriculture and forests, there is currently little scientific literature examining how continued warming will impact global biofuel production.

One 2020 study found that bioethanol availability globally could drop – by 23% under a “very high emissions scenario” and by 4.3% under a “low emissions” scenario by 2060 – “if climate change risk is not adequately mitigated” and corn continues to be the dominant feedstock.

The study “encourages” changing out corn for switchgrass as a key source of bioethanol.

Another 2021 study examining the viability of China’s planned biofuel targets estimated that energy crop yields in China in the 2050s will decrease significantly compared to the 2010s, due to the impacts of climate change.

It found that climate change is expected to have a “substantial impact” on the land available for biofuel production in the 2050s, under both scenarios used in the study.

Gurgel, from MIT, tells Carbon Brief that it is “very hard to take into account how much climate change will damage bio-energy production” at this point, given the uncertainty of what emissions pathway the world will follow.

While most climate models “do a very good job” at forecasting average temperature change in the future, they do an “average job” at projecting rainfall change, or how many extreme weather events countries will see in the future, he says.

This is important because many biofuel crops, such as sugarcane and palm oil, are water-intensive and thrive in regions with abundant rainfall, but yields may fail in drier parts of the world that could see more drought.

Given this “cascade of uncertainties”, he continues, “we don’t have a clear picture of how bad the future [of agriculture] will be – we just know it will be more challenging than today”.

Delaney, meanwhile, asks whether investing in biofuels, which will be impacted by climate change, is a “good investment” for the long term. He tells Carbon Brief:

“I think these are the questions that we need to ask ourselves when we see – not just in India, but Indonesia, Brazil, everywhere around the world right now – this growing appetite for biofuels. Can we really keep the promises that we made at the end of the day?”

The post Q&A: How countries are using biofuels to meet their climate targets appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: How countries are using biofuels to meet their climate targets

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 21 November 2025: [COP30 DeBriefed] ‘Mutirão’ text latest; ‘Roadmaps’ explained; COP finish times plotted

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Key ‘mutirão’ text emerges

‘MUTIRÃO’ 2.0: After many late nights, but little progress – and a dramatic fire at the COP30 venue – the much-awaited second draft of the summit’s key agreement, called the “mutirão” text, finally dropped this morning. The new mutirão text “calls for efforts to triple adaptation finance” by 2030 and would launch a presidency-led “Belém mission to 1.5C” alongside a voluntary “implementation accelerator”, as well as a series of “dialogues” on trade. It “decides to establish” a two-year work programme on climate finance, including on a key section of the Paris Agreement called Article 9.1, but has a footnote saying this will not “prejudge” how the climate finance goal agreed last year is met.

ROADMAPS TO NOWHERE: The latest draft does not refer to the idea of a “fossil-fuel roadmap”, which is not on the COP30 agenda, but has been pushed by Brazil’s president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva and a group of parties (see below). A letter to the presidency, seen by Carbon Brief and reportedly backed by at least 29 countries, including Colombia, Germany, Palau, Mexico and the UK, says: “We cannot support an outcome that does not include a roadmap [on fossil fuels].” It also flags the lack of a roadmap on deforestation. The letter asks for a revised text.

PLENARY WHEN: The latest draft of the mutirão text is unlikely to be the last. There is also a set of draft decisions that have not been fully resolved. For instance, this morning, the Brazilian COP presidency floated a draft decision on what it is calling the “Belém gender action plan”, with three brackets versus the 496 brackets in the previous version. At a short, informal stocktaking plenary, COP30 president André Corrêa do Lago invited countries to react to the drafts in a “mutirão” meeting, namely, in the “spirit of cooperation”. But expect all timings to be flexible, as they work to iron out differences in closed-door meetings.

Adaptation COP

TRIPLING TARGET: A new text for the global goal on adaptation dropped alongside the mutirão text this morning, after days of tense negotiations. Crucially, it includes the adoption of some of the indicators, which will be used to track countries’ progress on adaptation. Last week, the African Group and others called for the indicators not to be adopted at COP30 – one of the key expectations ahead of the summit – and, instead, a two-year work programme to further refine them due to concerns around adaptation finance.

INDICATORS: The latest text adopts an annex of 59 of the potential 100 indicators, emphasises that they “do not create new financial obligations or commitments” and decides to establish a two-year “Belém-Addis vision” on adaptation to further refine the indicators. The only remaining bracket within the text is to allow for the addition of the final adaptation finance target from the mutirão – which, currently, “calls for efforts to triple adaptation finance compared to 2025 levels by 2030”.

WHAM BAM: The latest text for another key negotiating stream on the “just transition work programme” (JTWP) “decides to develop a just transition mechanism”. This has been a point of particular contention within negotiations. Civil society developed the concept of the Belém Action Mechanism (BAM) over the past year and the G77 and China, a large group of global-south nations, tabled it within the JTWP in the first week. However, there was pushback from the EU, UK and others, with the former instead proposing an “action plan” as an alternative.

CRITICAL MINERALS: While landing on the inclusion of a mechanism is being welcomed by civil society and others, the latest text removes the reference to critical minerals included in its predecessor. If included, it would be the first time a reference to “critical minerals” is adopted in the JTWP.

Around the COP

- Turkey will host COP31, while Australia will take on the presidency and lead the negotiations, under a compromise deal reached between the two nations on Thursday, Reuters reported.

- Brazil set out a plan before COP30 to reform the “action agenda” – which includes 117 “plans to accelerate solutions” outside of the negotiations, covering everything from fossil-fuel phaseout to “sustainable diets for all”. On Wednesday, the presidency rounded off a series of events that have been used to promote this vision.

- China called for the creation of a “practical roadmap” for delivering climate finance by developed countries, which delegation head Li Gao said would help “prevent further erosion of trust between developed and developing countries”.

- An estimated 70,000 people marched in 32C heat in Belém on Saturday, marking the largest COP protest since COP26 in Glasgow.

52

The number of COP30 agenda items that had been agreed by the time DeBriefed was sent to readers.

51

The number of COP30 agenda items not yet agreed.

Latest climate research

- A five-year drought in Iran and around the Euphrates and Tigris basins “would have been very rare” without human-caused climate change | World Weather Attribution

- Integrating nature-based solutions into urban planning could reduce daytime temperatures by 2C during hot periods | Nature Cities

- Warming of the “deep Greenland basin” has exerted “obvious impacts” on the deep waters of the Arctic Ocean | Science Advances

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

This week saw the Brazilian presidency pledge to conclude some of the most controversial issues at COP30 a whole two days early. In the end, no early deal materialised. As the event approaches its official end time later today, with none of the major negotiations finished, this chart serves to remind that COPs have not finished on time for more than two decades.

Spotlight

‘Roadmaps’ explained

This week, Carbon Brief explains the push for new “roadmaps” away from fossil fuels and deforestation at COP30.

Speaking during the world leaders summit in Belém ahead of COP30, Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva said that the world “need[s] roadmaps to justly and strategically reverse deforestation [and] overcome dependence on fossil fuels”.

His words appeared to spark a movement of countries to call for new roadmaps away from fossil fuels and deforestation to feature as key outcomes of this COP – despite not being on the official agenda for the negotiations.

While momentum for each roadmap has grown, they were referenced only as an option in the first version of COP30’s key text, called the “global mutirão” – and in the second version the reference to roadmaps has disappeared entirely.

Below, Carbon Brief explains the origins of each roadmap, how support for them has grown and how they might feature in COP’s final outcome.

Fossil-fuel roadmap

Most people cite Lula’s pre-COP speech as the start of the movement for a fossil-fuel roadmap.

However, an observer close to the process told Carbon Brief that the COP30 presidency had, in fact, been consulting on the possibility of a roadmap months earlier – drawing help from the Beyond Oil and Gas Alliance, a small group of nations who have pledged to phase out all fossil fuels.

While Brazil was the first country to support the fossil-fuel roadmap, it was joined in the first few days of COP by eight Latin American countries that form the Alliance of Latin America and the Caribbean (AILAC) and by the Environmental Integrity Group (EIG), which includes Mexico, Liechtenstein, Monaco, South Korea, Switzerland and Georgia.

The call for a roadmap was also backed by the Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS), a group of 39 small low-lying island nations.

As momentum grew, the first global mutirão text appeared on Wednesday 19 November. Paragraph 35 of the text listed three options for where a reference to a fossil-fuel roadmap map might be incorporated, including one option for “no text”.

Later that day, ministers and climate envoys from more than 20 countries united for a packed-out press conference, where they called the current reference to the fossil-fuel roadmap “weak”, adding that it must be “strengthened and adopted”.

At the sidelines of the conference, UK climate envoy Rachel Kyte told journalists that around 80 countries now backed the call for a roadmap. (Carbon Brief obtained the list of 82 countries that have expressed their support.)

However, COP30 CEO Ana Toni told a press conference later that day that a “great majority” of country groups they had consulted saw a fossil-fuel roadmap as a “red line”.

In an interview with Carbon Brief, Dr Osama Faqeeha, deputy environment minister for Saudi Arabia, refused to be drawn on whether a fossil-fuel roadmap was a red line, but said:

“I think the issue is the emissions, it’s not the fuel. And our position is that we have to cut emissions regardless.”

The next day, the EU officially threw its weight behind the call for a fossil-fuel roadmap, after initial delay caused by hesitation to join the movement from Italy and Poland, Climate Home News reported.

The EU circulated its own proposal for how a fossil-fuel roadmap could be referenced in the global mutirão text, the publication added.

However, the latest version of the global mutirão text, released today, does not reference a roadmap at all. It has already sparked condemnation from a range of countries and observers.

It is expected that at least one more iteration of the text will emerge before the COP30 presidency attempts to find agreement, which could see a reference to the roadmap reappear.

Deforestation roadmap

While Lula called for roadmaps away from both fossil fuels and deforestation, the latter has received less attention, with one observer joking to Carbon Brief it had become the “sad forgotten cousin”.

A roadmap away from deforestation was originally only backed by Brazil, the EIG and AILAC.

However, the EU became a relatively early backer – announcing its support for a deforestation roadmap before a fossil-fuel roadmap.

The Democratic Republic of the Congo – one of the world’s “megadiverse” nations and one of the countries responsible for the Congo rainforest – has also announced its support. (See Carbon Brief’s list of supporters.)

As with the fossil-fuel roadmap, a reference to a deforestation roadmap appeared in the first iteration of the mutirão text, but has disappeared from the second. It may – or may not – appear in another version of the text before COP30’s finale.

Watch, read, listen

FOREST TALES: In a new video series from Earthday.org and the Pulitzer Centre, three investigative journalists discussed their reporting on deforestation in Brazil and the Democratic Republic of the Congo.

AI IMPACTS: Google CEO, Sundar Pichai, spoke to BBC News about the climate impacts of AI, among other topics.

MISSING DATA: Columnist George Monbiot wrote in the Guardian about the “vast black hole” of climate data in some parts of the world – which he says is a “gift” to climate deniers.

Coming up

- 22-23 November: G20 summit, Johannesburg, South Africa

- 24 November-5 December: 20th meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on International Trade in Endangered Species (CITES), Samarkand, Uzbekistan

- 24-29 November: 11th session of the governing body of the International Treaty on Plant Genetic Resources for Food and Agriculture, Lima, Peru

Pick of the jobs

- Department for Energy Security and Net Zero, chief press officer | Salary: £60,620-£67,565. Location: London

- World Bank Group, climate change specialist | Salary: Unknown. Location: New Delhi, India

- University of Buffalo, Center for Climate Change and Health Equity, postdoctoral associate | Salary: $50,000-$55,000. Location: Buffalo, New York

- University of Oxford, Queens College, junior fellow in climate change research | Salary: £37,694. Location: Oxford, UK

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 21 November 2025: [COP30 DeBriefed] ‘Mutirão’ text latest; ‘Roadmaps’ explained; COP finish times plotted appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Cropped 19 November 2025: COP30 edition

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

COP30 nears its end

COP TALK: The COP30 climate summit is entering its final days in Belém – and food, forests and land have all featured across the two weeks of talks. The formal agriculture negotiations track at climate COPs is the Sharm-el-Sheikh joint work on climate action for agriculture and food security (SWJA). Talks, however, came to an abrupt halt last Thursday evening, with countries agreeing to continue discussions on a draft text – with elements ranging from agroecology to precision agriculture – in Bonn next year.

DEFORESTATION ROADMAP: WWF and Greenpeace called for a roadmap at COP30 to end deforestation. There has been a lot of chatter about roadmaps in Belém, with more than 80 countries backing calls for a roadmap for phasing out fossil fuels, the Guardian said. Kirsten Schuijt from WWF told a press conference that a similar plan on ending deforestation should include “real actions and ambition to bend the curve on forest loss”. Writing for Backchannel, Colombia’s environment minister Irene Vélez-Torres said: “We need to see the global north come behind a roadmap – and quickly”. (Carbon Brief’s Daisy Dunne has started tracking the countries in favour, such as Colombia.)

CARBON MARKETS: Elsewhere at the talks, nature-based solutions featured in an early draft text of carbon market negotiations. (Carbon Brief’s Aruna Chandrasekhar took a closer look at some of these references.) In addition, the Brazilian presidency launched a global coalition of “compliance carbon markets” on 7 November, which was endorsed by 18 countries.

BIG AG IN BELÉM: More than 300 industrial agriculture lobbyists attended COP30, according to an investigation by DeSmog and the Guardian. This is a 14% increase on last year, DeSmog reported, and larger than Canada’s entire delegation. One in four agricultural lobbyists attended the talks as part of an official country delegation, the outlet noted. Elsewhere, Unearthed found that the sustainable agriculture pavilion at COP30 was “sponsored by agribiz interests linked to deforestation and anti-conservation lobbying”. Brazilian outlet Agência Pública reported that Brazil placed the “billionaire brothers” who own JBS, the world’s largest beef producer, on a “VIP list” at the summit.

TRACKING PROGRESS: A UN report found that while progress has been made towards a global pledge to cut methane emissions by 30% by 2030, emissions of the potent greenhouse gas continue to rise. The report said agricultural methane is projected to increase by 4-8% by 2030, but could instead reduce by 8% with methane-reduction measures. Elsewhere, a report covered by Down to Earth found that countries need more than 1bn hectares of land, “an area larger than Australia”, to meet carbon removal pledges.

Indigenous presence in Belém

QUESTIONED PARTICIPATION: Ahead of COP30, Brazil’s presidency had expected the arrival of 3,000 Indigenous peoples in Belém. Indigenous peoples from the Amazon were at COP30 “in greater numbers than ever before”, with 900 representatives granted access to the negotiations, the New York Times reported. However, only four people from Brazil’s afro-descendant Quilombolas communities held such accreditation, Climate Home News and InfoAmazonia reported. A boat journey that took 62 Indigenous representatives across the Amazon river to attend the COP30 was covered by Folha de São Paulo, Reuters and El País.

VARIED DEMANDS: Indigenous leaders arrived in Belém with a variety of demands, including the inclusion of their land rights within countries’ climate plans, the New York Times added. It wrote that land demarcation “would provide legal protection against incursion by loggers, farmers, miners and ranchers”. Half of the group that sailed across the Amazon river were youths that brought demands from Amazon peoples to the climate summit, El País reported. A small Indigenous group from Cambodia attended COP30 to combat climate disinformation and call for ensuring Indigenous rights in forest projects, Kiri Post reported.

FROM BLOCKADES TO THE STREETS: During the first week of COP30, Indigenous protesters blocked the entrance of the conference and clashed with police officers when demanding climate action and forest protection, Reuters reported. Tens of thousands of protesters, including Indigenous peoples, took to the streets of Belém on Saturday to demand climate justice and hold a funeral for fossil fuels, Mongabay and the Guardian reported.

News and views

AGRI DISASTERS: Disasters have driven $3.26tn in agricultural losses worldwide over the past 33 years, amounting to around 4% of global agricultural GDP, according to a new report from the UN Food and Agriculture Organization. The report assessed how disasters – including droughts, floods, pests and marine heatwaves – are disrupting food production, livelihoods and nutrition. It found that Asia saw nearly half of global losses, while Africa recorded the highest proportional impacts, losing 7.4% of its agricultural GDP.

WATER ‘CATASTROPHE’: Iran is facing “nationwide catastrophe” due to “worsening droughts, record-low rainfall and decades of mismanaged water resources”, Newsweek reported. According to Al Jazeera, the country is facing its sixth consecutive drought year, following high summertime temperatures. The outlet added: “Iran spends 90% of its water on low-yield agriculture in a pursuit of self-sufficiency that exacerbates drought.” BBC News reported that authorities in the country have “sprayed clouds” with salts to “induce rain, in an attempt to combat” the worsening drought.

TRUMP THREAT: The Trump administration will allow oil and gas drilling in Alaska’s North Slope – home to “some of the most important wildlife habitat in the Arctic” – the New York Times reported. The announcement reverses a decision made during the Biden administration to restrict development in half of the National Petroleum Reserve in Alaska, the newspaper said. Separately, Reuters reported that the US Department of Agriculture directed its staff to identify grants for termination at the start of Trump’s second administration by searching for “words and phrases related to diversity and climate change”.

FIELDS FLATTENED: Thousands of acres of sugarcane plantations in the Philippines’ Visayas islands were destroyed by Typhoon Tino earlier this month, the Philippine Star reported. Damages to the country’s sugar industry have been estimated at 1.2bn Philippine dollars (£15.5m), it added. Sugar regulator administrator Pablo Luis Azcona told the Manila Times: “We have seen entire fields decimated by Tino, especially in the fourth and fifth districts of Negros Occidental, where harvestable canes were flattened and flooded. We can only hope that these fields will be able to recover.”

FARMS AND TREES: EU countries and the European parliament have provisionally agreed on an “overhaul” of farming subsidies, Reuters reported. The changes would “exempt smaller farmers from baseline requirements tying their subsidies to efforts to protect the environment” and increase their potential payments, the newswire said. Campaigners told Reuters that these changes would make farmers more vulnerable to climate change. Elsewhere, Bloomberg said EU countries are “pushing for a one-year delay” of the bloc’s planned anti-deforestation law – “seeking more time to comply” with the law compared to different proposed changes from the European Commission.

ANOTHER FUND: Brazil is mulling over the creation of a new fund for preserving different biomes, such as the Cerrado, inspired by the Amazon Fund, Folha de São Paulo reported. Discussions are underway between Brazil’s president and the Brazilian Development Bank (BNDES), according to the newspaper. Separately, the Washington Post reported on how Brazil’s efforts to position itself as a climate leader at COP30 has been undermined by Lula’s approval of new oil drilling in the Amazon and elimination of environmental permits.

Spotlight

Key COP30 pledges

This week, Carbon Brief outlines four of the biggest COP30 initiatives for food, land and forests.

Tropical Forest Forever Facility

Brazil’s tropical forest fund – arguably the biggest forest announcement from this year’s climate talks – was hailed by WWF and others as a “gamechanger” upon its launch almost two weeks ago. Since then, the fund has raised $5.5bn – far below even Brazil’s reduced target of $10bn by next year.

Norway, Brazil, Indonesia, Portugal, France and the Netherlands have all committed to pay into the fund, while Germany has said it will announce its contribution soon. The UK and China, on the other hand, do not plan to pay in.

Intergovernmental Land Tenure Commitment

This new “landmark” commitment aimed to “recognise and strengthen” the land rights on 160m hectares of Indigenous peoples and local community land by 2030, according to the Forest & Climate Leaders’ Partnership.

It has been backed by 14 countries, including Brazil, Colombia, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Indonesia and the UK.

Relatedly, $1.8bn has been pledged from public and private funding to help secure land rights for Indigenous peoples, local communities and Afro-descendent communities in forests and other ecosystems.

Belém Declaration on Hunger, Poverty and People-Centered Climate Action

Signatories of this declaration committed to a number of actions aiming to address the “unequal distribution of climate impacts”, including expanding social protection systems and supporting climate adaptation for small farmers.

It was adopted by 43 countries and the EU. A German minister described it as a “pioneering step in linking climate action, social protection and food security”.

Belém 4X

This initiative aimed to gather high-level support to quadruple the production and use of “sustainable fuels”, such as hydrogen and biofuels, by 2035.

It was launched by Brazil and has been backed by 23 countries so far, including Canada, Italy, Japan and the Netherlands.

However, the pledge has been “rejected” by some NGOs, including Climate Action Network and Greenpeace, who criticised the environmental impact of biofuels.

Watch, read, listen

FOOD CHAT: Bite the Talk, a podcast by the Global Alliance for Improved Nutrition, explored the “critical intersection of climate change and nutrition”.

TRUE SAVIOURS: On Instagram, the Washington Post published a list of 50 plant and animal species that “have enriched and even saved human lives”.

NO MORE WASTE: A comment piece by the founder of London’s Community Kitchen in the Independent addressed the relevance of food waste to the climate agenda.

FOREST FRENZY: The Financial Times spoke to Amazon climate scientist Prof Carlos Nobre about tipping points and his “zeal for saving the rainforest”.

New science

- Floods led to a 4.3% global reduction in annual rice yield over 1980-2015, with crop losses accelerating after the year 2000 – “coinciding with a climate change-induced uptick in the frequency and severity” of floods | Science Advances

- Loss of African montane forests led to local “microclimate” warming of 2.0-5.6C over 2003-22, diminishing the “temperature-buffering capacity” of the forests | Communications Earth & Environment

- “Prolonged” drought is linked to an increase in conflict between humans and wildlife – especially carnivores | Science Advances

In the diary

- 10-21 November: COP30 UN climate summit | Belém, Brazil

- 22-23 November: G20 leaders’ summit | Johannesburg, South Africa

- 24-29 November: 11th session of the governing body of the international treaty on plant genetic resources for food and agriculture | Lima, Peru

- 1-5 December: XIX World Water Congress | Marrakech, Morocco

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz. Ayesha Tandon also contributed to this issue. Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 19 November 2025: COP30 edition appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

COP30: Carbon Brief’s second ‘ask us anything’ webinar

As COP30 reaches its midway point in the Brazilian city of Belém, Carbon Brief has hosted its second “ask us anything” webinar to exclusively answer questions submitted by holders of the Insider Pass.

The webinar kicked off with an overview of where the negotiations are on Day 8, plus what it was like to be among the 70,000-strong “people’s march” on Saturday.

At present, there are 44 agreed texts at COP30, with many negotiating streams remaining highly contested, as shown by Carbon Brief’s live text tracker.

Topics discussed during the webinar included the potential of a “cover text” at COP30, plus updates on negotiations such as the global goal on adaptation and the just-transition work programme.

Journalists also answered questions on the potential for a “fossil-fuel phaseout roadmap”, the impact of finance – including the Baku to Belém roadmap, which was released the week before COP30 – and Article 6.

The webinar was moderated by Carbon Brief’s director and editor, Leo Hickman, and featured six of our journalists – half of them on the ground in Belém – covering all elements of the summit:

- Dr Simon Evans – deputy editor and senior policy editor

- Daisy Dunne – associate editor

- Josh Gabbatiss – policy correspondent

- Orla Dwyer – food, land and nature reporter

- Aruna Chandrasekhar – land, food systems and nature journalist

- Molly Lempriere – policy section editor

A recording of the webinar (below) is now available to watch on YouTube.

Watch Carbon Brief’s first COP30 “ask us anything” webinar here.

The post COP30: Carbon Brief’s second ‘ask us anything’ webinar appeared first on Carbon Brief.

-

Climate Change3 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases3 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Greenhouse Gases1 year ago

Greenhouse Gases1 year ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change1 year ago

Climate Change1 year ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Renewable Energy4 months ago

US Grid Strain, Possible Allete Sale