The first-ever international conference on the contentious topic of “overshoot” was held last week in a palace in the small town of Laxenburg in Austria.

The three-day conference brought together nearly 200 researchers and legal experts to discuss future temperature pathways where the Paris Agreement’s “aspirational” target to limit global warming to 1.5C is met “from above, rather than below”.

Overshoot pathways are those which exceed the 1.5C limit – before being brought back down again through techniques that remove carbon from the atmosphere.

The conference explored both the feasibility of overshoot pathways and the legal frameworks that could help deliver them.

Researchers also discussed the potential consequences of a potential rise – and then fall – of global temperatures on climate action, society and the Earth’s climate systems.

Speaking during a plenary session, Prof Joeri Rogelj, a professor of climate science and policy at Imperial College London, said that “moving into a world where we exceed 1.5C and have to manage overshoot” was an exercise in “managing failure”.

He said that it was “essential” that this failure was acknowledged, explaining that this would help set out the need to “minimise and manage” the situation and clarify the implications for “near-term action” and “long-term [temperature] reversal”.

Below, Carbon Brief draws together some of the key talking points, new research and discussions that emerged from the event.

- Defining overshoot

- Mitigation ambition and 1.5C viability

- Carbon removal

- Impacts of overshoot

- Adaptation

- Legal implications and loss and damage

- Communication challenges and next steps

Defining overshoot

The study of temperature overshoot has grown in recent years as the prospects of limiting global temperature rise to 1.5C have dwindled.

Conference organiser Dr Carl-Friedrich Schleussner – a senior research scholar at the International Institute for Applied Systems Analysis (IIASA) – explained the event was designed to bring together different research communities working on a “new field of science”.

He told Carbon Brief:

“If we look at [overshoot] in isolation, we may miss important parts of the bigger picture. That’s why we also set out the conference with very broad themes and a very interdisciplinary approach.”

The conference was split between eight conference streams: mitigation ambition; carbon dioxide removal (CDR); Earth system responses; climate impacts; tipping points; adaptation; loss and damage; and legal implications.

There was also a focus on how to communicate the concept of overshoot.

In simple English, “overshoot” means to go past or beyond a limit. But, in climate science, the term implies both a failure to meet a target – as well as subsequent action to correct that failure.

Today, the term is most often deployed to describe future temperature trajectories that exceed the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C limit – and then come back down.

(In the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change’s (IPCC’s) fifth assessment cycle, completed in 2014, the term was used to describe a potential rise and then fall of CO2 concentrations above levels recommended to meet long-term climate goals. A recent “conceptual” review of overshoot noted this was because, at the time, CO2 concentrations were the key metric used to contextualise emissions reductions).

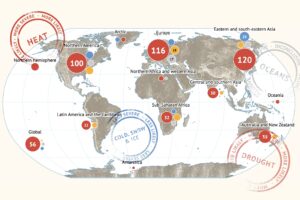

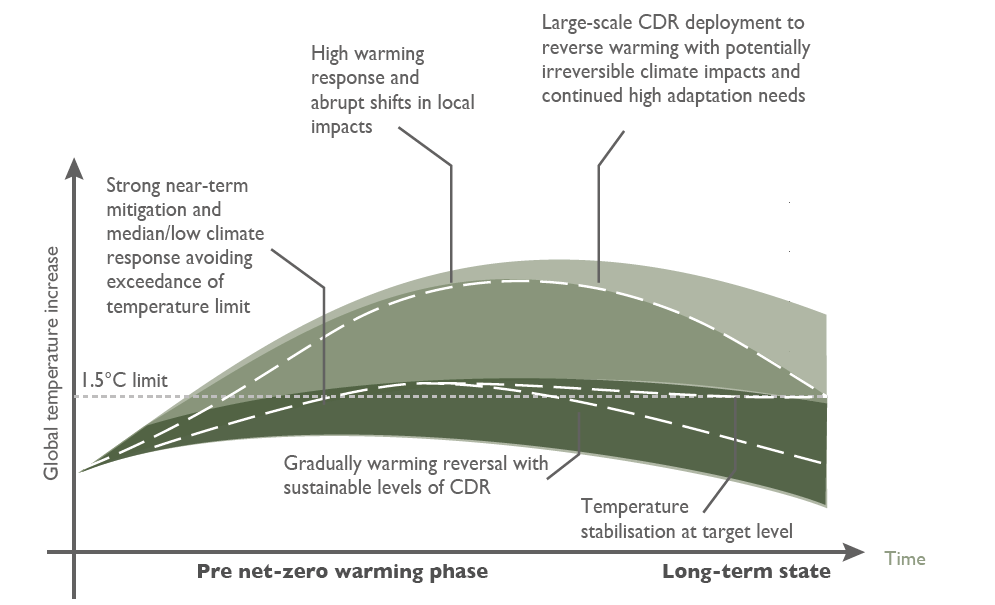

The plot below provides an illustration of three overshoot pathways. The most pronounced pathway sees global temperatures rise significantly above the 1.5C limit – before eventually falling back down again as carbon dioxide is pulled from the atmosphere at scale.

In the second and third pathways, global temperature rise breaches the limit by a smaller margin, before either falling enough just to stabilise around 1.5C, or dropping more dramatically due to larger-scale carbon removals.

In an opening address to delegates, Prof Jim Skea, who is the current chair of the IPCC, acknowledged the scientific interpretation of overshoot was not intuitive to non-experts.

“The IPCC has mainly used two words in relation to overshoot – “exceeding” and “limiting”. To a lay person, these can sound like opposites. Yet we know that a single emissions pathway can both exceed 1.5C in the near term and limit warming to 1.5C in the long term.”

Noting that different research communities were using the term differently, Skea urged researchers to be precise with terminology and stick to the IPCC’s definition of overshoot:

“We should give some thought to communication and keep this as simple as possible. When I look at texts, I hear more poetic words like “surpassing” and “breaching”. I would urge you to keep the range of terms as small as possible and make sure that we’re absolutely using them consistently.”

In the glossary for its latest assessment cycle, AR6, the IPCC defines “overshoot” pathways as follows:

IIASA’s Schleussner stressed that not all pathways that go beyond 1.5C qualify as overshoot pathways:

“The most important understanding is that overshoot is not any pathway that exceeds 1.5C. An overshoot pathway is specific to this being a period of exceedance. It is going to come back down below 1.5C.”

Mitigation ambition and 1.5C viability

Perhaps the most prominent topic during the conference was the implications of overshoot for global ambition to cut carbon emissions and the viability of the 1.5C limit.

Opening the conference, IIASA director general Prof Hans Joachim Schellnhuber shared his personal view that “1.5C is dead, 2C is in agony and 3C is looming”.

In a pre-recorded keynote speech, Ralph Regenvanu, Vanuatu’s minister for climate change, called for a rejection of the “normalisation of overshoot” and argued that “we must treat 1.5C as the absolute limit that it is” and avoid backsliding. He added:

“Minimising peak warming must be our lodestar, because every tenth of a degree matters.”

Prof Skea opened his keynote with some theology:

“I’m going to start with the prayer of St Augustine as he struggled with his youthful longings: ‘Lord grant me chastity and continence, but not yet.’ And it does seem that this is the way that the world as a whole is thinking about 1.5C: ‘Lord, limit warming to 1.5C above pre-industrial levels, but not yet.’”

Referencing the “lodestar” mentioned by Regenvanu, Skea warned that it is light years away and, “unless we act with a sense of urgency, [1.5C is] likely to remain just as remote”.

Speaking to Carbon Brief on the sidelines of the conference, Skea added:

“We are almost certain to exceed 1.5C and the viability of 1.5C is now much more referring to the long-term potential to limit it through overshoot.”

Schleussner told Carbon Brief that the framing of 1.5C in the conference is “one that further solidifies 1.5C as the long-term limit and, therefore, provides a backstop against the idea of reducing or backsliding on targets”.

If warming is going to surpass 1.5C, the next question is when temperatures are going to be brought back down again, Schleussner added, noting that there has been no “direct” guidance on this from climate policy:

“The [Paris Agreement’s] obligation to “pursue efforts” [to limit global temperature rise by 1.5C] points to doing it as fast as possible. Scientifically, we can determine what this means – and that would be this century. But there’s no clear language that gives you a specific date. It needs to be a period of overshoot – that is clear – and it should be as short as possible.”

In a parallel session on the “highest possible mitigation ambition under overshoot”, Prof Joeri Rogelj, professor of climate science and policy at Imperial College London, outlined how the recent ruling from the International Court of Justice (ICJ) provides guidance to countries on the level of ambition in their climate pledges under the Paris Agreement, known as “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs). He explained:

“[The ruling] highlights that the level of NDC ambition is not purely discretionary to a state and that every state must do its utmost to ensure its NDC reflects the highest possible ambition to meet the Paris Agreement long-term temperature goal.”

Rogelj presented some research – due to be published in the journal Environmental Research Letters – on translating the ICJ’s guidance “into a framework that can help us to assess whether an NDC indeed is following a standard of conduct that can represent the highest level of ambition”. He showed some initial results on how the first two rounds of NDCs measure up against three “pillars” covering domestic, international and implementation considerations.

In the same session, Prof Oliver Geden, senior fellow and head of the climate policy and politics research cluster at the German Institute for International and Security Affairs and vice-chair of IPCC Working Group III, warned that the concept of returning temperatures back down to 1.5C after an overshoot is “not a political project yet”.

He explained that there is “no shared understanding that, actually, the world is aiming for net-negative”, where emissions cuts and CDR together mean that more carbon is being taken out of the atmosphere than is being added. This is necessary to achieve a decline in global temperatures after surpassing 1.5C.

This lack of understanding includes developed countries, which “you would probably expect to be the frontrunners”, Geden said, noting that Denmark is the “only developed country that has a quantified net-negative target” of emission reductions of 110% in 2050, compared to 1990 levels. (Finland also has a net-negative target, while Germany announced its intention to set one last year. In addition, a few small global-south countries, such as Panama, Suriname and Bhutan, have already achieved net-negative.)

Geden pondered whether developed countries are a “little bit wary to commit to going to net-negative territory because they fear that once they say -110%, some countries will immediately demand -130% or -150%” to pay back a larger carbon debt.

Carbon removal

To achieve a decline in global temperatures after an initial breach of 1.5C would require the world to reach net-negative emissions overall.

There is a wide range of potential techniques for removing CO2 from the atmosphere, such as afforestation, direct air capture and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS). Captured carbon must be locked away indefinitely in order to be effective at reducing global temperatures.

However, despite its importance in achieving net-negative emissions, there are “huge knowledge gaps around overshoot and carbon dioxide removal”, Prof Skea told Carbon Brief. He continued:

“As it’s very clear from the themes of this conference, we don’t altogether understand how the Earth would react in taking carbon dioxide out of the atmosphere. We don’t understand the nature of the irreversibilities. And we don’t understand the effectiveness of CDR techniques, which might themselves be influenced by the level of global warming, plus all the equity and sustainability issues surrounding using CDR techniques.”

Skea notes that the seventh assessment cycle of the IPCC, which is just getting underway, will “start to fill these knowledge gaps without prejudging what the appropriate policy response should be”.

Prof Nebojsa Nakicenovic, an IIASA distinguished emeritus research scholar, told Carbon Brief that his “major concern” was whether there would be an “asymmetry” in how the climate would respond to large-scale carbon removal, compared to its response to carbon emissions.

In other words, he explained, would global temperatures respond to carbon removal “on the way down” in the same way they did “on the way up” to the world’s carbon emissions.

Nakicenovic noted that overshoot requires a change in focus to approaching the 1.5C limit “from above, rather than below”.

Schleussner made a similar point to Carbon Brief:

“We may fail to pursue [1.5C] from below, but it doesn’t relieve us from the obligation to then pursue it from above. I think that’s also a key message and a very strong overarching message that’s going to come out from the conference that we see…that pursuing an overshoot and then decline trajectory is both an obligation, but it also is well rooted in science.”

Reporting back to the plenary from one of the parallel sessions on CDR, Dr Matthew Gidden, deputy director of the Joint Global Change Research Institute at the Pacific Northwest National Laboratory, also noted another element of changing focus:

“When we’re talking about overshoot, we have become used to, in many cases, talking about what a net-zero world looks like. And that’s not a world of overshoot. That’s a world of not returning from a peak. And so communicating instead about a net-negative world is something that we could likely be shifting to in terms of how we’re communicating our science and the impacts that are coming out of it.”

On the need for both CDR and emissions cuts, Gidden noted that the discussions in his session emphasised that “CDR should not be at the cost of mitigation ambition”. But, he added, there is still the question of how “we talk about emission reductions needed today, but also likely dependence on CDR in the future”.

In a different parallel session, Prof Geden also made a similar point, noting that “we have to shift CDR from being seen as a barrier to ambition to an enabler of even higher ambition, but not doing that by betting on ever more CDR”.

Among the research presented in the parallel sessions on CDR was a recent study by Dr Jay Fuhrman from the JGCRI on the regional differences in capacity to deploy large-scale carbon removal. Ruben Prütz, from the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, presented on the risks to biodiversity from large-scale land-based CDR, which – in some cases – could have a larger impact than warming itself.

In another talk, the University of Oxford’s Dr Rupert Stuart-Smith explored how individual countries are “depending very heavily on [carbon] removals to meet their climate targets”. Stuart-Smith was a co-author on an “initial commentary” on the legal limits of CDR, published in 2023. This has been followed up with a “much more detailed legal analysis”, which should be published “very soon”, he added.

Impacts of overshoot

Since the Paris Agreement and the call for the IPCC to produce a special report on 1.5C, research into the impacts of warming at the aspirational target has become commonplace.

Similarly, there is an abundance of research into the potential impacts at other thresholds, such as 2C, 3C and beyond.

However, there is comparatively little research into how impacts are affected by overshoot.

The conference included talks on some published research into overshoot, such as the chances of irreversible glacier loss and lasting impacts to water resources. There were also talks on work that is yet to be formally published, such as the risks of triggering interacting tipping points under overshoot.

Speaking in a morning plenary, Prof Debra Roberts, a coordinating lead author on the IPCC’s forthcoming special report on climate change and cities and a former co-chair of Working Group II, highlighted the need to consider the implications of different durations and peak temperatures of overshoot.

For example, she explained, it is “important to know” whether the impacts of “overshoot for 10 years at 0.2C above 1.5C are the same as 20 years at 0.1C of overshoot”.

Discussions during the conference noted that the answer may be different depending on the type of impact. For heat extremes, the peak temperature may be the key factor, while the length of overshoot will be more relevant for cumulative impacts that build up over time, such as sea level rise.

Similarly, if warming is brought back down to 1.5C after overshoot, what happens next is also significant – whether global temperature is stabilised or net-negative emissions continue and warming declines further. Prof Schleussner told Carbon Brief:

“For example, with coastal adaptation to sea level rise, the question of how fast and how far we bring temperatures back down again will be decisive in terms of the long-term outlook. Knowing that if you stabilise that around 1.5C, we might commit two metres of sea level rise, right? So, the question of how far we can and want to go back down again is decisive for a long-term perspective.”

One of the eight themes of the conference centred specifically on the reversibility or irreversibility of climate impacts.

In his opening speech, Vanuatu’s Ralph Regenvanu warned that “overshooting 1.5C isn’t a temporary mistake, it is a catalyst for inescapable, irreversible harm”. He continued:

“No level of finance can pull back the sea in our lifetimes or our children’s. There is no rewind button on a melted glacier. There is no time machine for an extinct species. Once we cross these tipping points, no amount of later ‘cooling’ can restore our sacred reefs, it cannot regrow the ice that already vanished and it cannot bring back the species or the cultures erased by the rising tides.”

As an example of a “deeply, deeply irreversible” impact, Dr Samuel Lüthi, a postdoctoral research fellow in the Institute of Social and Preventive Medicine at the University of Bern, presented on how overshoot could affect heat-related mortality.

Using mortality data from 850 locations across the world, Lüthi showed how projections under a pathway where warming overshoots 1.5C by 0.1-0.3C, before returning to 1.5C by 2100 has 15% more heat-related deaths in the 21st century than a pathway with less than 0.1C of overshoot.

His findings also suggested that “10 years of 1.6C is very similar [in terms of impacts] to five years of 1.7C”.

Extreme heat also featured in a talk by Dr Yi-Ling Hwong, a research scholar at IIASA, on the implications of using solar geoengineering to reduce peak temperatures during overshoot.

She showed that a world where a return to 1.5C had been achieved through geoengineering would see different impacts from a world where 1.5C was reached through cutting emissions. For example, in her modelling study, while geoengineering restores rainfall levels for some regions in the global north, significant drying “is observed in many regions in the global south”.

Similarly, a world geoengineered to 1.5C would see extreme nighttime heat in some tropical regions that is more severe than in a 2C world with no geoengineering, Hwong added.

In short, she said, “this implies the risk of creating winners and losers” under solar geoengineering and “raises concerns about equity and accountability that need to be considered”.

After describing how overshoot features in the outlines of the forthcoming AR7 reports in his opening speech, Prof Skea told Carbon Brief that he expects a “surge of papers” on overshoot in time to be included.

But it was important to emphasise that a “lot of the science that people have been carrying out is relevant within or without an overshoot”, he added:

“At points in the future, we are not going to know whether we’re in an overshoot world or just a high-emissions world, for example. So a lot of the climate research that’s been done is relevant regardless of overshoot. But overshoot is a new kind of dimension because of this issue of focus on 1.5C and concerns about its viability.”

Adaptation

The implications of overshoot temperature pathways for efforts to prepare cities, countries and citizens for the impacts of climate change remains an under-researched field.

Speaking in a plenary, Prof Kristie Ebi – a professor at the University of Washington’s Center for Health and the Global Environment – described research into adaptation and overshoot as “nascent”. However, she stressed that preparing society for the impacts associated with overshoot pathways was as important as bringing down emissions.

She told Carbon Brief that there were “all kinds of questions” about how to approach “effective” adaptation under an overshoot pathway, explaining:

“At the moment, adaptation is primarily assuming a continual increase in global mean surface temperature. If there is going to be a peak – and, of course, we don’t know what that peak is – then how do you start planning? Do you change your planning? There are places, for instance when thinking about hard infrastructure, [where overshoot] may result in a change in your plan.”

IIASA’s Schleussner told Carbon Brief that the scientific community was only just “beginning to appreciate” the need to understand and “quantify” the implications of different overshoot pathways on adaptation.

In a parallel session, Dr Elisabeth Gilmore, associate professor in environmental engineering and public policy at Carleton University in Canada, made the case for overshoot modelling pathways to take greater account of political considerations.

“Not just, but especially, in situations of overshoot, we need to start thinking about this as much as a physical process as a socio-political process…If we don’t do this, we are really missing out on some key uncertainties.”

Current scenarios used in climate research – including the Shared Socioeconomic Pathways and Representative Concentration Pathways – are “a bit quiet” when it comes to thinking about governance, institutions and peace and conflict, Gilmore said. She added:

“Political institutions, legitimacy and social cohesion continue to shift over time and this is really going to shape how much we can mitigate, how much we adapt and especially how we would recover when adding in the dimension of overshoot.”

Gilmore argued that, from a social perspective, adaptation needs are greatest “before the peak” of temperature rise – because this is when society can build the resilience to “get to the other side”. She said:

“Orthodoxy in adaptation [research] that you always want to plan for the worst [in the context of adaptation, peak temperature rise]… But we don’t really know what this peak is going to be – and we know that the politics and the social systems are much more messy.”

Dr Marta Mastropietro, a researcher at Politecnico di Milano in Italy, presented the preliminary results of a study that used emulators – simple climate models – to explore how human development might be impacted under low, medium and high overshoot pathways.

Mastropietro noted how, under all overshoot scenarios studied, both the drop to the human development index (HDI) – an index which incorporates health, knowledge and standard of living – and uncertainty increases as the peak temperature increases.

However, she said “the most important takeaway” from the preliminary results was around society’s constrained ability to recover from damage.

“This percentage of damages that are absorbed is always less than 50%. So, even in the most optimistic scenarios of overshoot, we will not be able to reabsorb these damages, not even half of them. And this is considering a damage function which does not consider irreversible impacts like sea level rise.”

Meanwhile, Dr Inês Gomes Marques from the University of Lisboa in Portugal, shared the results of an as-yet-unpublished study investigating whether the Lisbon metropolitan area holds enough public spaces to offer heatwave relief to the population under overshoot scenarios. The 1,900 “climate refugia” counted by researchers included schools, museums and churches.

Marques noted that most of the population were found to be within one kilometre of a “climate refugia” – but noted that “nuances” would need to be added to the analysis, including a function which considers the limited mobility of older citizens.

She explained that the researchers were aiming to “establish a framework” for this type of analysis that would be relevant to both the science community and municipalities tasked with adaptation. She added:

“The main point is that we need to think about this now, because we will face some big problems if we don’t”.

Legal implications and loss and damage

Significant attention was given throughout the conference to the legal considerations of the breach of – and impetus to return to – the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C warming limit.

This included discussions about how the international legal frameworks should be updated for an “overshoot” world where countries would need to pursue “net-negative” strategies to bring temperatures down to 1.5C.

There were also discussions around governance of geoengineering technologies and the fairness and justice considerations that arise from the real-world impacts of breached targets.

The conference was being held just months after the ICJ’s advisory decision that limiting temperature increase to 1.5C should be considered countries’ “primary temperature goal”.

IIASA’s Shleussner told Carbon Brief that the decision provided “clarity” that countries had a “clear obligation to bring warming back to 1.5C”. He added:

“We may fail to pursue it from below, but it doesn’t relieve us from the obligation to then pursue it from above.”

Prof Lavanya Rajamani, professor of international environmental law at the University of Oxford, insisted that “1.5C was very much alive and well in the legal world”, but noted there were “very significant limits” to what could be achieved through the UN Framework Convention for Climate Change (UNFCCC) – the global treaty for coordinating the response to climate change – both today and in the future.

Summarising discussions around how countries can be pushed to deliver the “highest possible ambition” in future climate plans submitted to the UN, Rajamani urged delegates to be “tempered in [its] expectations of what we’re going to get from the international regime”. She added:

“Changing the narratives and practices at the national level are far more likely to filter up to the international level than trying to do it from a top-down perspective.”

In a parallel session, Prof Christina Voigt, a professor of international law at the University of Oslo, pointed out that overshoot would require countries to aspire beyond “net-zero emissions” as “the end climate goal” in national plans.

Stabilising emissions at “net-zero” by mid-century would result in warming above 1.5C, she explained, whereas “net-negative” emissions are required to deliver overshoot pathways that return temperatures to below the Paris Agreement’s aspirational limit. She continued:

“We will need frontrunners. Leaders, states, regions would need to start considering negative-emission benchmarks in their climate policies and laws from around mid-century. There will be an expectation that developed country parties take the lead and explore this ‘negativity territory’.”

Voigt added that it was “critical” that nations at the UNFCCC create a “shared understanding” that 1.5C remains the “core target” for nations to aim for, even after it has been exceeded. One possible place for such discussions could be at the 2028 global stocktake, she noted.

She said there would need to be more regulation to scale up CDR in a way that addresses “environmental and social challenges” and an effort to “recalibrate policies and measures” – including around carbon markets – to deliver net-negative outcomes.

In a presentation exploring governance of solar radiation management (SRM), Ewan White, a DPhil student in environmental law at the University of Oxford, said the ICJ’s recent advisory opinion could be interpreted to be “both for and against” solar geoengineering.

Countries tasked with drawing up global rules around SRM in an overshoot world would need to take a “holistic approach to environmental law”, White said. In his view, this should take into account international legal obligations beyond the Paris Agreement and consider issues of intergenerational equity, biodiversity protection and nations’ duty to cooperate.

Dr Shonali Pachauri, research group leader at IIASA, provided an overview of the equity and justice implications that might arise in an overshoot world.

First, she said that delays to emissions reductions today are “shifting the burden” to future generations and “others within this generation” – increasing the need for “corrective justice” and potential loss-and-damage payments.

Second, she said that adaptation efforts would need to increase – which, in turn, would “threaten mitigation ambition” given “constrained decision-making”.

Finally, she pointed to resource consumption issues that might arise in a world of overshoot:

“The different technologies that one might use for CDR often depend on the use of land, water, other materials – and this, of course, then means competing with many other uses [of resources].”

A separate stream focused on loss and damage. Session chair Dr Sindra Sharma, international policy lead at the Pacific Islands Climate Action Network, noted that the concept of loss and damage was “fundamentally transformed” by overshoot – adding there were “deep issues of justice and equity”.

However, Sharma said that the literature on loss and damage “has not yet deeply engaged with the specific concept of overshoot” despite it being “an important, interconnected issue”.

Sessions on loss and damage explored the existence of “hard social limits” under future overshoot scenarios, insurance and the need to bring more factors into assessments of habitability, including biophysical and social-economic constraints.

Communication challenges and next steps

At the conference, scientists and legal experts collaborated on a series of statements that summarised discussions at the conference – one for each research theme and an overarching umbrella statement.

IIASA’s Schleussner told Carbon Brief that the statements represented a “key outcome of the conference” that could provide a “framework” to guide future research.

Nevertheless, he noted that statements are a “work in progress” and set to be “further refined” following feedback from experts not able to attend the conference.

At the time of going to press, the overarching conference statement read as follows:

“Global warming above 1.5C will increase irreversible and unacceptable losses and damages to people, societies and the environment.

“It is imperative to minimise both the maximum warming and duration of overshoot above 1.5C to reduce additional risks of human rights violations and causing irreversible social, ecological and Earth system changes including transgressing tipping points.

“This is required by international law and possible by removing CO2 from the atmosphere and further reducing remaining greenhouse emissions.”

Conference organisers also pointed delegates to an open call for research on “pathways and consequences of overshoot” in the journal Environmental Research Letters. The special issue will be guest edited by a number of scientists who played a key role in the conference.

Meanwhile, communications experts at the conference discussed the challenges inherent in conveying overshoot science to non-experts, noting potential confusion around the word “overshoot” and the difficulties in explaining that the 1.5C limit, while breached, was still a goal.

Holly Simpkin, communications manager at the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, urged caution when communicating overshoot science to the general public:

“I don’t know whether ‘overshoot’ is an effective communication framing. It is an important scientific question, but when it comes to near-term action and the requirements that an ambitious overshoot pathway would ask of us, emissions are what are in our control.

“We could spend 10 more years defining this and, actually, it’s quite complex…I think it’s better to be honest about that and to try to be more simple in that frame of communication, knowing that this community is doing a wealth of work that provides a technical basis for those discussions.”

The post Overshoot: Exploring the implications of meeting 1.5C climate goal ‘from above’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Overshoot: Exploring the implications of meeting 1.5C climate goal ‘from above’

Climate Change

Q&A: Why does gas set the price of electricity – and is there an alternative?

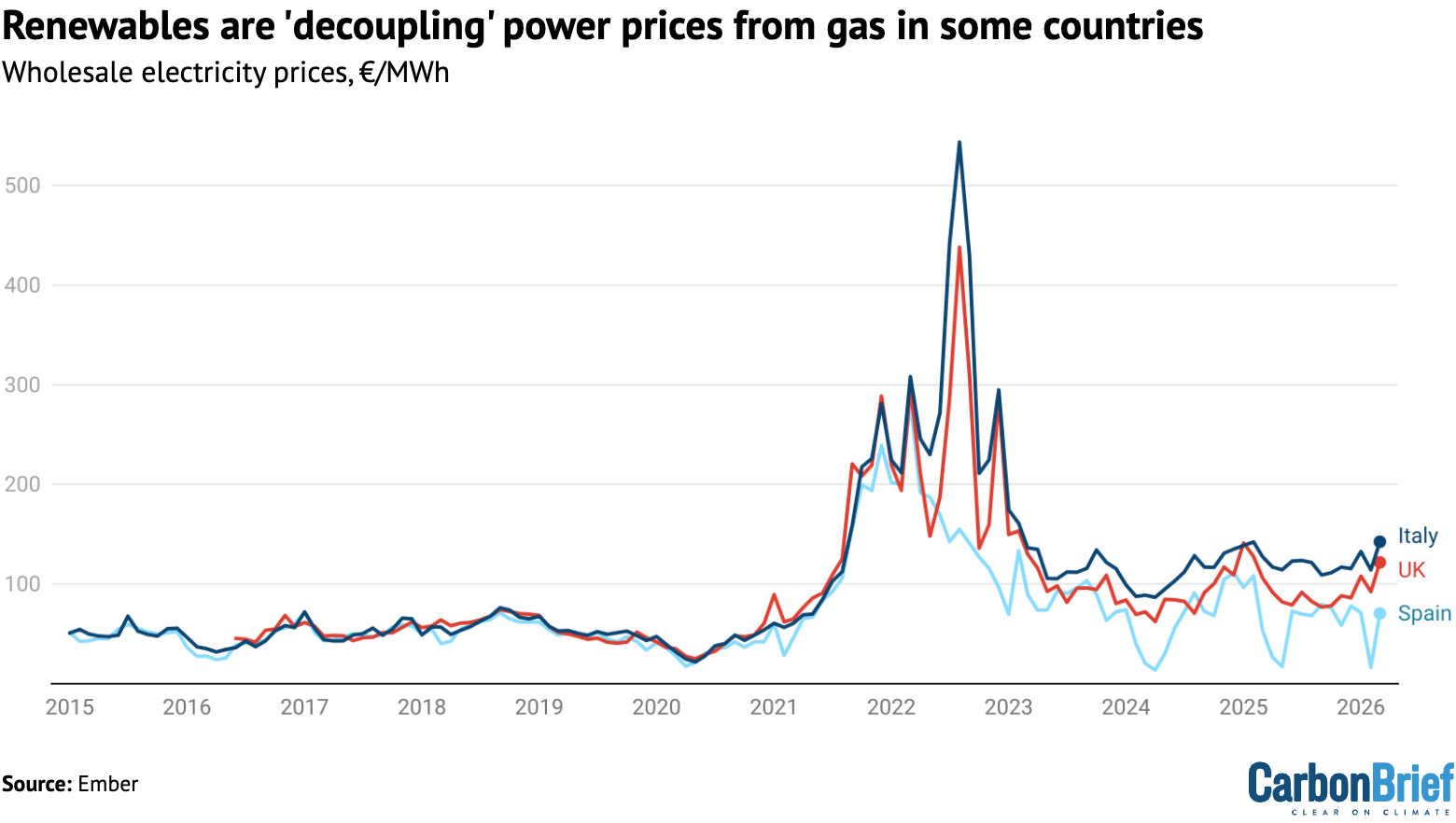

A surge in gas prices triggered by the Iran war has caused a knock-on spike in the price of electricity in the UK, Italy and many other European markets.

This is because gas almost always sets the price of power in these countries, even though a significant share of their electricity comes from cheaper sources.

This “coupling”, which is part of what UK energy secretary Ed Miliband calls the “fossil-fuel rollercoaster”, is due to the “marginal pricing” system used in most electricity markets globally.

After another fossil-fuel price shock, just four years after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, this coupling between gas and electricity prices is once again under the spotlight, in the UK and the EU.

There are various alternatives that have been put forward as ways to break – or “decouple” – the link between gas and electricity prices.

Electricity prices could be “decoupled” from gas prices by changing the way the market works, but ideas for doing this either have not been tested or have problems of their own.

Some people have implied that the UK could insulate itself from high and volatile international gas prices by extracting more gas from the North Sea.

However, contrary to false claims by, for example, the hard-right climate-sceptic Reform UK party, this would not be expected to cut energy bills, because gas prices are set on international markets.

Finally, electricity prices can be “decoupled” from gas by burning less of it, a shift that is nearly complete in Spain and that is already having an impact in the UK.

- Why does gas set the price of electricity?

- What is the impact of gas setting the electricity price?

- What market reforms have been proposed?

- Why is ‘marginal pricing’ in the news again?

- Would it help if more gas were extracted domestically?

- Would burning less gas stop it setting electricity prices?

Why does gas set the price of electricity?

In liberalised economies, electricity is bought and sold via market trading. The market uses a system called “marginal pricing” to match buyers with enough supply to meet their demand.

(The same system is used in most commodity markets, including for oil, gas or food products.)

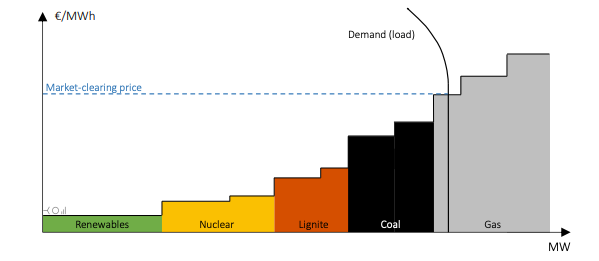

All of the power plants that are available to generate make “bids” to sell electricity at a particular price. The bids are arranged in a “merit order stack”, from the cheapest to the most expensive, shown in the illustrative schematic below.

This means that the price of gas sets the price of electricity, whenever gas plants are at the margin.

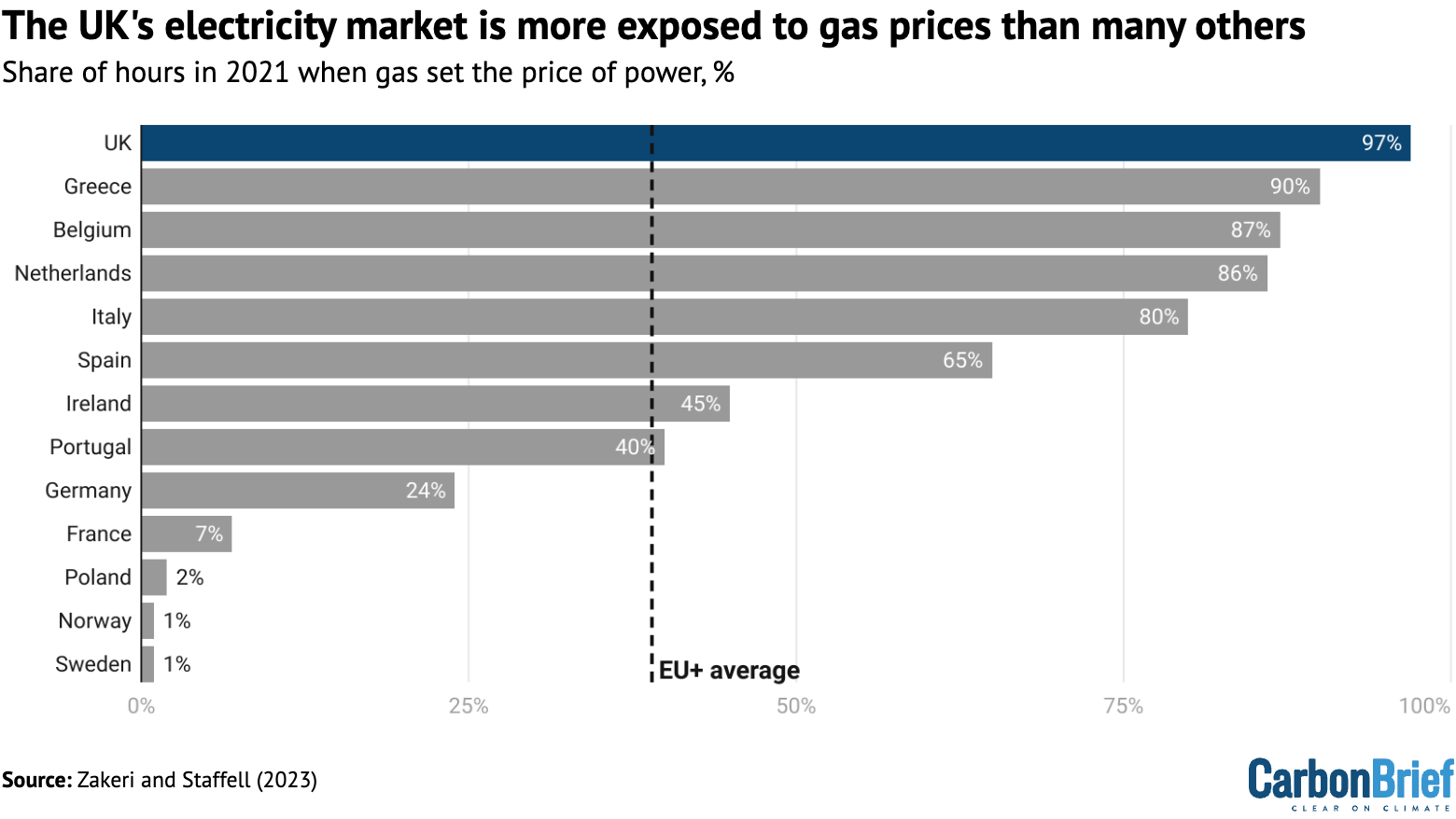

In the UK, the marginal unit is almost always a gas-fired power plant. As a result, one widely cited academic analysis found that gas set the price of power 97% of the time in the UK in 2021.

In contrast, the analysis found that gas only sets the price of power 7% of the time in France, as shown in the figure below. This is because the French market is dominated by nuclear power.

The “pay as clear” marginal-pricing system means that gas sets the price of power more often than might be expected, given its share of electricity generation overall.

For example, gas set the price of power 97% of the time in 2021, even though it only accounted for 37% of electricity generation that year. Equally, even though renewables now make up around half of UK electricity supplies, gas still usually sets the price of power in the UK.

(There are some important subtleties to this, due to the fact that not all gas-fired power plants are equally expensive to run. This is discussed further below.)

Overall, the fact that gas hardly ever sets the price of power in some European markets hints at the potential to decouple electricity prices from gas, by shifting towards alternative sources.

What is the impact of gas setting the electricity price?

The tight coupling of gas and electricity prices in the UK and other markets is the source of significant political debate, particularly during periods when the price of gas soars.

When gas prices hit record highs after Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, politicians, commentators and the media rushed to understand why this also spiked electricity bills.

The same dynamic is playing out in 2026, following the attacks on Iran by the US and Israel, the closure of the Strait of Hormuz and the resulting surge in international gas prices.

An editorial in the Financial Times published earlier this month is headlined: “The déjà vu of Europe’s energy shock.” It says the crisis is once again raising questions over electricity pricing:

“In Britain, in particular, questions remain on how to reform its electricity pricing, which currently leaves it highly exposed to volatile wholesale gas prices.”

This exposure is illustrated in the figure below, which shows the tight link between prices on the “day-ahead” markets for gas and electricity.

Indeed, recent analysis from the UK Energy Research Centre (UKERC), published before the Iran war, found that high gas prices were still the biggest driver of high UK electricity bills.

The UK is not the only market being hit by high electricity prices after the outbreak of war in the Middle East. Italy is also suffering, at a time when it was already in the midst of a major debate over how to cut electricity prices, which are also high due to its heavy reliance on gas power.

What market reforms have been proposed?

Historically, some governments set the price of electricity themselves. However, this is increasingly rare and most countries now have “liberalised” electricity markets to determine prices.

These markets use the “pay as clear” system of marginal pricing, described above, to balance supply and demand in each hour of the day.

Alternative models include “pay as bid”, where each power plant is only paid the amount that it bid to supply electricity, rather than the higher price of the marginal unit.

However, this “would not provide cheaper prices”, according to the European Commission, because bidders would seek to maximise their profits by guessing the clearing price:

“In the pay-as-bid model, producers (including cheap renewables) would simply bid at the price they expect the market to clear, not at zero or at their generation costs.”

Another option would be to create two separate markets, one “green power pool” for renewables and another for conventional sources of electricity.

One proponent of this idea is Prof Michael Grubb at University College London. In a March 2026 post on LinkedIn he says:

“The impact of surging gas prices on electricity will again highlight the oddities of our current electricity market – which make sense to many economists, but to hardly anyone else.”

Explaining his rationale for creating separate power markets, he continues:

“The crisis again emphasises that gas-generated power and renewables are not really the same commodity and deserve distinct and tailored market structures to also enhance transparency. Unless and until that occurs, no amount of policy tinkering can overcome the volatility imposed by geopolitical events outside our control.”

However, the UK government concluded in 2024 that it “[did] not consider [a green power pool] to be deliverable”, adding that, even if it were possible, it “would not provide additional benefits”.

This was part of the UK government “review of electricity market arrangements” (REMA), which considered – and then rejected – a series of alternative ways to structure the market.

Similarly, it is less than two years since the European Commission also considered – and then rejected – alternatives to the marginal pricing system, notes Jon Ferris, head of flexibility and storage at consultancy LCP Delta, in a LinkedIn post. The commission explains:

“This model provides efficiency, transparency and incentives to keep costs as low as possible. There is general consensus that the marginal model is the most efficient for liberalised electricity markets.”

In the UK, a debate in parliament in early March 2026 saw Labour MP Toby Perkins questioning the marginal pricing system, which he said was now “far less robust”. He said:

“Because renewables are cheaper, should we not look to benefit from that, rather than having a system that allows gas to set the price, even if it accounts for only 1% of our energy?”

Ultimately, however, marginal pricing is the “worst approach to clearing markets apart from all the others”, Ferris tells Carbon Brief.

The Iran crisis has also been used to resurface a more radical option, put forward last year by consultancy Stonehaven and NGO Greenpeace, of taking gas out of the market completely.

The idea would effectively see gas plants being taken into a strategic reserve, where they would receive a regulated return for remaining open. They would be managed centrally and called on to generate power as needed outside of the market, which would continue to use marginal pricing.

Adam Bell, partner at Stonehaven and the government’s former head of energy policy, tells Carbon Brief that it would be possible to implement within 18 months, but only if moving at a pace that the civil service might describe as “brave”.

Why is ‘marginal pricing’ in the news again?

Despite the decisions at UK and EU level to reject the alternatives, interest in moving away from marginal pricing has recently been reignited – even before the shock of the Iran war.

For example, in a speech in February, European Commission president Ursula von der Leyen said a recent meeting of member states had seen “intense discussion” over marginal pricing:

“We did not come to a conclusion. I want to be very clear on this one. But to the next European Council, I will bring different options and findings on whether it is time to move forward on the market design or whether we are still good on this market design.”

A subsequent leak from the commission, seen by Carbon Brief, also implies that marginal pricing is up for debate, as part of ongoing discussions on how to tackle high energy prices.

Subsequently, Philippe Lamberts, climate advisor to von der Leyen, made comments implying that the marginal pricing system was problematic.

In response, ahead of a meeting of EU governments in the week beginning 16 March, a group of seven member states wrote to the commission warning against market reform.

Their letter says that “no satisfactory alternative model has been identified” and that “all other options discussed would introduce inefficiencies”, compared with sticking to marginal pricing.

Industry group Eurelectric makes similar comments in its own letter, as well as warning about the uncertainty that would be created by market reform. It says:

“Delivering massive investments in clean power generation is the structural answer to reduce our dependence on fossil fuels. Reopening the fundamental principles of market design risks increasing uncertainty, delaying investment decisions and, ultimately, raising system costs.”

Another element to the debate has come from Italian government proposals to subsidise gas plants, in an effort to reduce electricity prices in the country.

The proposal has drawn comparisons with the so-called “Iberian mechanism”, under which the governments of Spain and Portugal subsidised gas power during the 2022 energy crisis.

This support did yield “short-term price relief”, says Chris Rosslowe, senior analyst at thinktank Ember in a post on LinkedIn. However, he says it also had “perverse consequences”, including increasing demand for gas “in the middle of a gas supply crisis”.

These sorts of ideas “would cause a lot of collateral damage” in terms of market efficiency, investor confidence and other areas, says Prof Lion Hirth at the Hertie School in Berlin, in a LinkedIn post.

Jean-Paul Harreman, director at consultancy Montel Analytics, writes in an article on LinkedIn:

“[R]eplacing transparent marginal pricing with political price formation is often like replacing a thermometer because you dislike the temperature reading. It may feel satisfying. It does not change the weather.”

Would it help if more gas were extracted domestically?

In the UK, there has also been intense pressure from opposition politicians and some sections of the media to expand gas production in the North Sea.

Nigel Farage, the climate-sceptic head of Reform UK, was recently quoted by Bloomberg as claiming: “Producing our own gas would reduce everybody’s electricity bills significantly.”

There is no evidence to support this claim.

While the opposition Conservatives have also been loudly calling for an expansion of North Sea drilling, they have been more circumspect about any impact on bills.

Writing in the Daily Telegraph, Conservative leader Kemi Badenoch only indirectly links such an expansion in domestic gas production with lower bills. She writes:

“[P]art of the reason we’re being hit so hard by [the Iran war] is because we are not drilling our own oil and gas thanks to [the government’s] net-zero madness.”

Badenoch’s own shadow energy secretary Claire Coutinho contradicted this idea in 2023, when she was in government. She said at the time that awarding new oil and gas licensing “wouldn’t necessarily bring energy bills down”.

This is because, as the UK’s energy minister Michael Shanks said at a recent event: “We will always be a price taker in international fossil-fuel markets, not a price maker.”

What he is saying is that UK gas production is small relative to the size of the European and global market for the fuel. As such, any increases in UK production would not materially affect prices.

Moreover, North Sea gas production has been in decline for decades and this is set to continue, whether or not the government allows new drilling to take place. This is because much of the gas it once contained has already been extracted and burned.

Would burning less gas stop it setting electricity prices?

The final idea for breaking the link between gas and electricity prices is simply to burn less gas.

This is one of the key motivations behind the UK government’s “clean power 2030” plan, which aims to largely decarbonise electricity supplies by 2030.

The government said when launching its plan:

“These investments will protect electricity consumers from volatile gas prices and be the foundation of a UK energy system that can bring down consumer bills for good.”

In 2026, however, UK electricity prices are still largely dictated by gas prices, as described above.

Yet this does not mean that the expansion of renewables has had no impact. Indeed, analysis by thinktank the Energy and Climate Intelligence Unit (ECIU) suggests that renewables have already reduced UK wholesale electricity prices by a third in 2025.

As more renewable generation is added to the system, the most expensive gas plants in the merit order “stack” are knocked out of the market. Even though another gas plant may still be setting power prices, it will be a cheaper and more efficient unit.

This intermediate impact of renewables is already visible when comparing electricity prices in the UK with those in Italy and Spain, as shown in the figure below.

The figure shows that UK wholesale electricity prices have been lower than those in Italy, as a result of the expansion of renewable sources over the past decade. (Prior to this, wholesale prices were similar in both countries.)

The contrast with prices in Spain is even larger , where Ember says “strong solar and wind growth [has] reduced the influence of expensive coal and gas power on the electricity market”.

The UK is already seeing electricity prices that are “decoupled” from gas prices on windy days. In addition, an increasing amount of electricity is set to be generated by renewable sources that hold “contracts for difference” (CfDs).

CfD projects are paid a fixed price for the electricity they generate, regardless of the price on the “day-ahead” wholesale market. As such, they dilute the impact of gas on consumer bills.

In 2022, when the last energy crisis hit, only 7% of UK generation was covered by CfDs, according to freelance “energy geek” Ben Watts. As of 2026, he says this has climbed to 13%.

By 2030, CfD projects will make up as much as half of total electricity supplies in the UK.

Callum McIver, research fellow at the University of Strathclyde and a member of the UKERC, tells Carbon Brief that CfDs are a “mechanism to decouple bills from the cost of gas”. He adds:

“With significant volumes of new and lower cost renewables on CfDs expected to connect to the system over the next few years, the impact of the scheme on price decoupling should accelerate…This provides an ever increasing hedge against future price shocks.”

Power-purchase agreements (PPAs) can have a similar effect. Here, large users such as industrial sites sign a contract with a power plant to buy the electricity they generate at a fixed price. Again, this takes some electricity out of the wholesale market, diluting the impact of gas prices.

Increases in UK renewable generation are yet to unseat gas from its role in determining electricity prices in most hours of the year, but this shift is starting to have an impact.

Analysis by consultancy Modo Energy suggests that electricity prices in the UK were above the price of gas power in nearly 90% of hours in 2018, a figure that had fallen to below 80% in 2024. Modo’s director Ed Porter said on Twitter: “The link between gas and power prices is weakening.”

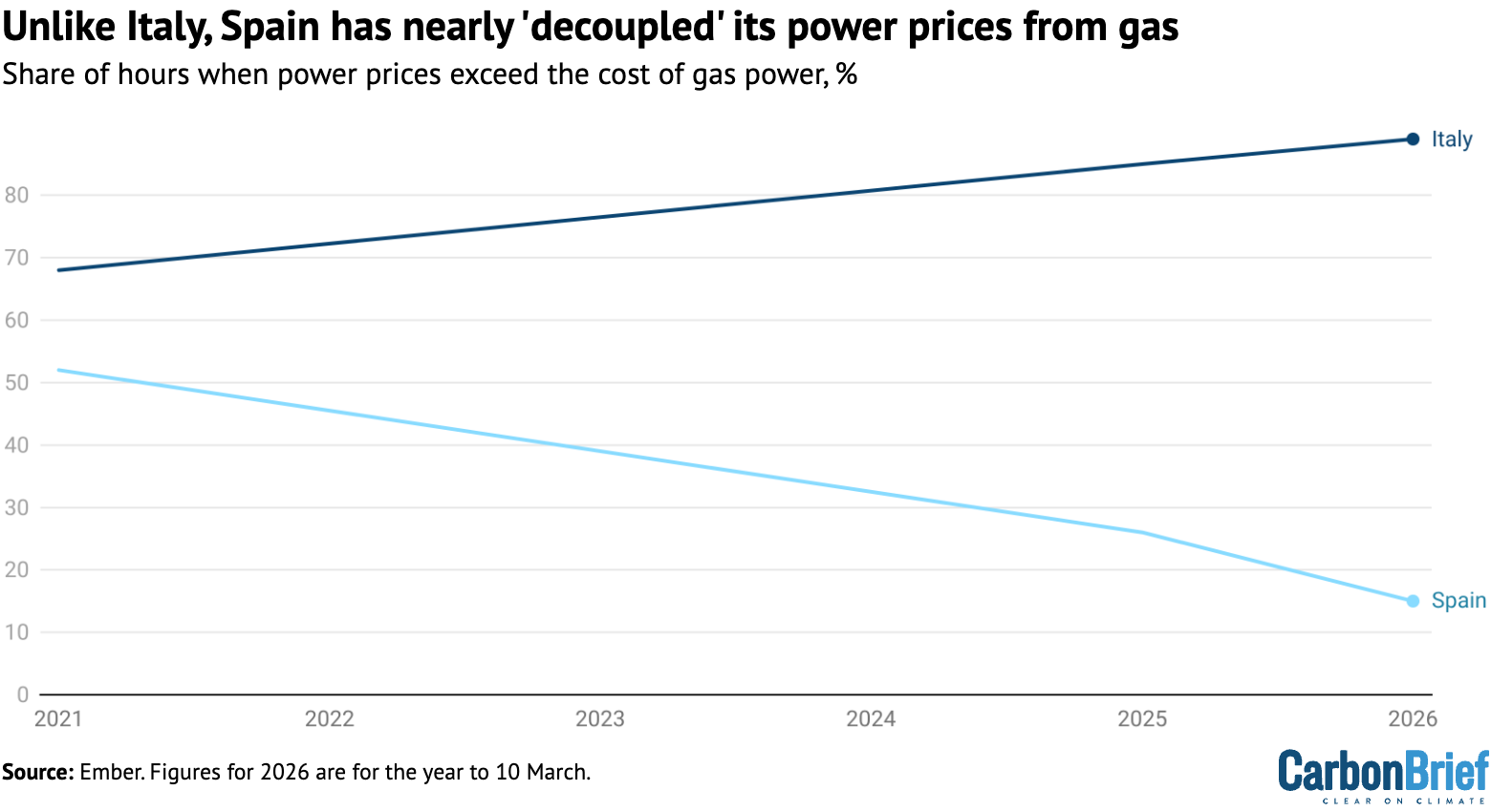

In Spain, analysis by Ember shows that the link is well on the way to being completely broken. Ember data shared with Carbon Brief shows that power prices were above the cost of gas power in 52% of hours in 2021, but this had fallen to 15% of hours in 2026 to date.

This data, shown in the figure below, is in stark contrast with Italy, where the influence of gas on electricity prices has actually increased in recent years.

A similar effect would be possible for the UK. Recent analysis from LCP Delta shows that the UK electricity system would be “almost entirely insulated from gas price shocks”, if it reaches the government’s clean-power 2030 targets.

Posting on LinkedIn, Sam Hollister, principal and head of UK market strategy, writes that a spike in gas prices similar to current levels would only increase household bills by 8%, if the 2030 targets are met. In contrast, bills would rise by 45%, if no CfD-backed renewables were on the system.

In his LinkedIn article, Montel’s Harreman concludes:

“The real structural solution to high power prices is not to mute marginal pricing, but to reduce exposure to fossil fuels and accelerate clean capacity, grids and flexibility. That lowers marginal costs structurally rather than cosmetically.”

“Marginal pricing is uncomfortable in volatile times. But discomfort is not evidence of failure. It is often evidence that the system is telling the truth. And, in energy markets, obscuring the truth is usually more expensive than confronting it.”

The post Q&A: Why does gas set the price of electricity – and is there an alternative? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: Why does gas set the price of electricity – and is there an alternative?

Climate Change

DeBriefed 13 March 2026: War and oil | Why gas drives electricity prices | Japan’s ‘vulnerability’ to Iran crisis

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

War and oil

HISTORIC: Leaders from 32 countries agreed to the “biggest emergency oil release in history” in response to the energy crisis sparked by the Iran war, reported Politico. The coordinated release of 400m barrels of oil by member nations of the International Energy Agency (IEA) is “more than twice” the amount released following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine in 2022, the outlet continued.

$100 BARREL: The agreement came as oil surged past $100 a barrel for the first time in four years on Monday, as “traders bet widening conflict in the Middle East would lead to weeks-long supply disruptions”, said the Financial Times. According to a report from the US Energy Information Administration, crude oil prices are likely to remain above $95 a barrel in the next two months, before falling to around $70 by the end of this year, reported Reuters. Research consultancy Wood Mackenzie, meanwhile, said oil prices could yet reach $150 per barrel, according to Reuters.

KREMLIN: The war in Iran has pushed up demand for Russian oil and gas, with the nation making €6bn (£5bn) in fossil-fuel sales in the last fortnight, according to analysis by the Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air covered by the Guardian. Read Carbon Brief’s Q&A on what the war means for the energy transition and climate action.

Around the world

- FLOODS: A month’s worth of rain in 24 hours triggered floods that killed more than 40 people in Kenya, reported the country’s Daily Nation newspaper.

- NET-ZERO: A new report from the UK’s Climate Change Committee outlined that achieving net-zero by 2050 will have less of a financial impact than the kind of fossil-fuel price rises experienced during the 2022 energy crisis, reported Carbon Brief.

- SOLAR: The amount of solar energy installed in the US fell by 14% between 2024 and 2025, according to an industry report, reported the New York Times.

- WATCHING: A Paris Agreement “watchdog” will discuss this month how to respond to countries who have failed to submit their latest national climate plan, Climate Home News reported, adding that about a third of countries are yet to submit more than a year after the deadline.

99%

The amount by which UK gas production in the North Sea is set to fall by 2050, when compared to 2025, as a result of a long-term decline in the basin.

97%

The amount by which North Sea gas production is set to decline from 2025 to 2050 if the government allows new drilling, according to new Carbon Brief analysis.

Latest climate research

- One-third of the world’s population lives in areas where heat and humidity would “severely limit activity for younger adults” | Environmental Research: Health

- The increase in extreme fire weather over 1980-2023 bears a “clear externally-forced signal” that is attributable to human-caused climate change | Science

- More than 85,000 social media posts from commuters in Boston, London and New York reveal “widespread thermal discomfort” in metro systems | Nature Cities

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

Gas almost always sets the price of power in the UK and many other European countries, due to the “marginal pricing” system used in most electricity markets. A new Carbon Brief Q&A explored why this is the case and whether there are alternatives.

Spotlight

Japan’s ‘vulnerability’ to Iran energy crisis

Carbon Brief talks to experts about the implications of the Iran war for Japan’s energy and economy.

Japan, the world’s fifth largest economy and eighth largest greenhouse gas emitter, is among the countries reeling from the energy crisis fuelled by war in Iran.

Japan’s energy system is “structurally dependent” on imported fossil fuels, making the country “highly vulnerable” to geopolitical shocks, Yuri Okubo, a senior researcher at the Renewable Energy Institute in Tokyo, told Carbon Brief.

Japan currently imports 87% of its energy supply, with the vast majority of that coming from fossil fuels. According to the IEA, 36% of its total supply is met by oil alone.

Some 95% of Japan’s oil comes from the Middle East, with about 70% travelling via the Strait of Hormuz – a crucial shipping route currently under effective blockade, reported Reuters.

That means approximately two-thirds of Japan’s oil supply could currently be prevented from reaching its destination.

‘80 million barrels’

On Wednesday, as the International Energy Agency called for an emergency release of global oil reserves, Japanese prime minister Sanae Takaichi announced she would “release” 45 days of stockpiled oil, the largest volume in Japan’s history, according to the Asahi Shimbun.

This is only a portion of the 254 days of oil Japan has stockpiled, but if a supply shortage were to become severe, the prime minister may have to consider “restriction of energy usage”, like that seen during the oil shocks of the 1970s, Ichiro Kutani, director of the energy security unit at the Institute of Energy Economics, told Carbon Brief.

In 1973, the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries (OAPEC) launched an oil embargo against countries suspected of supporting Israel during the 1973 Yom Kippur war, including Japan.

The subsequent shock for Japan’s economy was a major factor in the country’s shift from heavy industries to lighter industries such as electronics, academics have said.

Kutani told Carbon Brief:

“The failure to achieve the goal of reducing dependence on the Middle East for crude oil – pursued for more than 50 years since the 1970s oil crisis – is a bitter lesson.”

‘Nuclear’

On Monday, an opposition leader called on Takaichi to reopen Japan’s remaining fleet of nuclear power plants “as a carbon-free power source with less dependence on overseas sources”.

Prior to the Fukushima disaster in 2011, nuclear power provided roughly 30% of Japan’s electricity.

All 54 of Japan’s nuclear power plants were taken offline in 2011 after the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear plant meltdowns.

Over the past decade these have been slowly coming back online, but 18 out of 33 operable plants remain closed.

Takaichi has previously been vocal in her support of restarting Japan’s fleet of nuclear power plants, but developments in Iran “may add urgency to the debate”, Yuko Nakano of the Center for Strategic and International Studies told Carbon Brief.

Takeo Kikkawa, president of the International University of Japan, told S&P Global that the expansion of renewables has played a role in making up the shortfall from less nuclear power, adding:

“Now, with nuclear reduced to about 8%, renewables, especially solar, have increased to make up some of the difference. But overall, the combined self-sufficiency rate is still only about 15%.”

‘US-Japan summit’

Takaichi has so far resisted condemning or endorsing the attacks on Iran and refrained from making an assessment on the legality of US-Israeli strikes.

This could change next week, however, when she meets president Donald Trump for a US-Japan summit arranged before the war broke out.

In Washington DC, she may be expected to provide a more “full-throated endorsement” of the US war effort, “if not an outright request for Japan to dispatch its forces in support of US military activities in the Persian Gulf,” Tobias Harris, founder of Japan Foresight, a Japan-focused advisory firm in the US, said in a statement.

The Japanese government was already increasing oil imports from the US to diversify after the supply shocks from the Russia-Ukraine war – a trend that will likely be “further encouraged” by the Middle East war, said Dr Jennifer Sklarew, assistant professor of energy and sustainability at George Mason University. She told Carbon Brief:

“The overall effect of the war in the Middle East, thus, may be greater Japanese dependence on US oil and gas.”

Watch, read, listen

PLEDGE WATCH: The Cypress Climate Advisory group released a “NDC benchmarker” that monitors countries’ emissions against their nationally determined contributions (NDC) under the Paris Agreement.

FEMALE LEADERSHIP: A comment piece in Climate Home News explored why women’s leadership is “central” to unlocking the global phaseout of fossil fuels.

NOW OR NEVER: Martin Wolf, the chief economics commentator at the Financial Times, argued that one of the economic lessons from the Iran war is the “need to invest in renewables, in order to reduce vulnerability”.

Coming up

- 9-19 March: 31st Annual Session of the International Seabed Authority, Kingston, Jamaica

- 15 March: Republic of the Congo presidential election

- 15 March: Vietnam parliamentary election

Pick of the jobs

- Grantham Institute for Climate Change, assistant professor or associate professor | Salary: £70,718-£80,148 or £82,969. Location: London

- Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), China analyst | Salary: Unknown. Location: Remote/London

- Climate Action Network, campaign officer | Salary: £31,069-£33,140. Location: Flexible

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 13 March 2026: War and oil | Why gas drives electricity prices | Japan’s ‘vulnerability’ to Iran crisis appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Q&A: How climate change and war threaten Iran’s water supplies

Climate change, war and mismanagement are putting Iran’s water supply under major strain, experts have warned.

The Middle Eastern country has faced years of intense drought, which scientists have found was made more intense due to human-caused climate change.

In recent years, Iranian citizens have protested against the government’s management of water supplies, pointing the blame at decades of poor planning and shortsighted policies.

As water supplies run low, authorities warned last year that several of Iran’s major cities – including the capital, Tehran – could soon face “water day zero”, when a city’s water service is turned off and existing supplies rationed.

Meanwhile, recent air strikes on desalination plants in Iran and Bahrain are driving wider questions about how the war might exacerbate water insecurity across the Middle East.

One expert tells Carbon Brief the conflict is “straining an already-fragile [water] system” within Iran.

In this article, Carbon Brief looks at how conflict is combining with climate change and unsustainable use to place pressure on Iran’s water supplies.

- How close are Iran’s major cities to a ‘water day zero’?

- What role is climate change playing?

- What other factors are involved?

- How could attacks on desalination plants impact water supplies in the Middle East?

- What policies could help Iran avoid a ‘water day zero’?

How close are Iran’s major cities to a ‘water day zero’?

Iran is one of the most water-stressed countries in the world and is currently in the grips of an unprecedented, multi-year drought.

The country’s hot and dry climate means that freshwater is scarce. However, many Iranian citizens also blame decades of government mismanagement for the present-day water shortages.

In January, the Guardian explained that over multiple decades, Iranian officials abandoned the country’s “qanat aquifer system”, which consists of tens of thousands of tunnels dug into hillsides across the country that lead to underground water storage. This system has been “supplying [Iran’s] cities and agriculture with freshwater for millennia”, the newspaper said.

To replace the aquifer system, the government built dozens of dams over the second half of the 20th century, which together hold around a quarter of the country’s total water resource, according to the Guardian. However, it added:

“But by putting major dams on rivers too small to sustain them, the authorities brought short-term relief at the cost of longer-term water loss: evaporation from reservoirs increased while upland areas were deprived of water, now trapped behind the dams.”

Yale Environment 360 noted in December that “in the past half century, around half of Iran’s qanats have been rendered waterless through poor maintenance or as pumped wells have lowered water tables within hillsides”.

Agriculture is responsible for 90% of Iran’s water use. Over 2003-19, Iran lost around 211 cubic kilometres of groundwater – around twice the country’s annual water consumption – largely due to unregulated water pumping for farming.

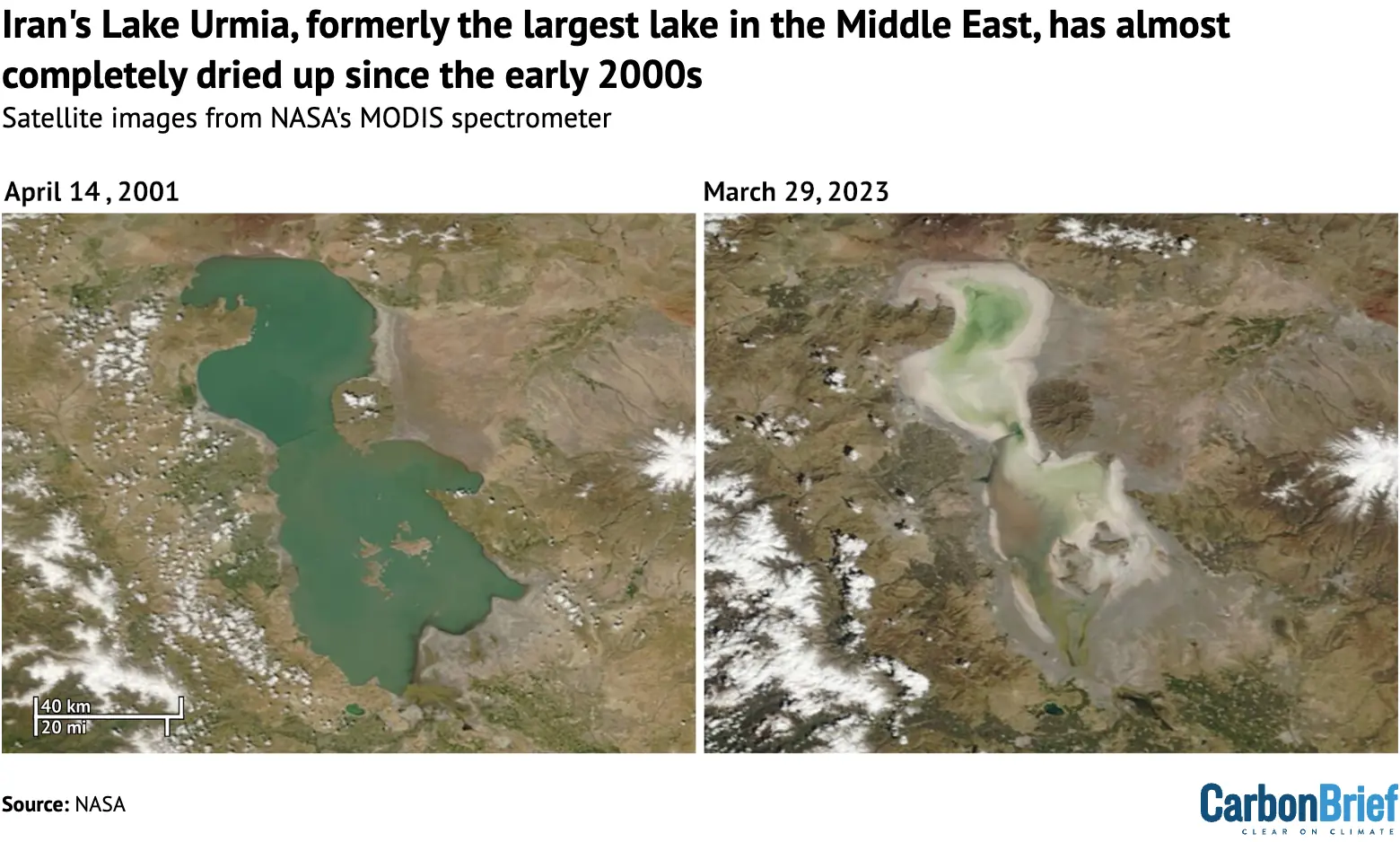

The images below show how Lake Urmia in the north-west of the country – once the largest lake in the Middle East – has almost completely dried up since 2001 as water that feeds that lake has been diverted.

Towards the end of 2025, Iran’s Meteorological Organisation warned that the main dams supplying drinking water to major cities, such as Tehran, Tabriz and Mashhad, were close to “water day zero”.

The term “water day zero” has been used by academics, media and governments to describe the moment when a city or region’s municipal water supply becomes so depleted that authorities have to turn off taps and implement water rationing. It has been used to describe water crises in Cape Town, South Africa and Chennai, India.

In a televised national address in November, Iranian president Masoud Pezeshkian reportedly said the government had “no other choice” but to relocate the capital due to “extreme pressure” on water, land and infrastructure systems.

(This came after the government announced in January it would relocate its capital to the southern coastal region of Makran, citing Tehran’s enduring overpopulation, power shortages and water scarcity.)

Tehran is home to 10 million people and consumes nearly a quarter of Iran’s water supplies.

The water shortages have fuelled nation-wide protests, which have been often-violently suppressed by the government.

Prof Kaveh Madani, former deputy vice-president of Iran and the director of the UN University Institute for Water, Environment and Health, tells Carbon Brief that recent rainfall means the threat of “water day zero” has subsided in Iran in recent months.

However, he stresses that a combination of climate change and “local human factors” mean “many, many places in Iran are in ‘water bankruptcy’ mode”.

“Water bankruptcy” is when water systems have been overused to the point they can no longer meet demand without causing irreversible damage to the environment, according to Madani’s own research.

What role is climate change playing?

Iran is currently facing its sixth year of consecutive drought conditions.

An update posted in November by the National Iranian American Council quoted Mohsen Ardakani – managing director of Tehran Water and Wastewater Company – as saying:

“We are entering our sixth consecutive drought year. Since the start of the 2025-26 water year (about a month ago), not a single drop of rain has fallen anywhere in the country.”

The country’s most recent “water year”, which ran from September 2024 to September 2025, was one of the driest on record. Over the 12-month period, the country recorded 81% less rainfall than the historical average.

Meanwhile, temperatures in Iran can soar above 50C in the hot season, pushing the limits of human survivability and exacerbating water loss through evaporations from reservoirs of water.

Multiple attribution studies have shown that climate change is making the country’s hot and dry conditions more intense and likely.

In 2023, the World Wealth Attribution service (WWA) carried out an analysis on the drought conditions in Iran over 2020-23.

This study investigated agricultural drought, which focuses on the difference between rainfall amounts and levels of evapotranspiration from soils and plants.

The study explored how often a drought of a similar intensity would have occurred in a world without warming and how often it could occur in the climate of 2023. The researchers found that the drought would have been a one-in-80 year event without global warming, but a one-in-five year event in 2023’s climate.

They added that if the planet continues to heat, reaching a warming level of 2C above pre-industrial temperatures, Iran could expect a drought of 2023’s severity, on average, every other year.

The graphic below illustrates these results, where a pink dot indicates the number of years in every 81 with an event like the 2020-23 drought over Iran.

The box on the left shows how often such a drought would be expected in a pre-industrial climate, in which there is no human-driven warming. The box in the centre shows 2023’s climate, which has warmed 1.2C as a result of human-caused climate change. The box on the right shows a world in which the climate is 2C warmer than in the pre-industrial period.

Two years later, WWA carried out another study on drought in Iran, this time focusing on the five-year drought over 2021-25. The authors found an “even stronger impact” of climate change than their previous analysis.

A range of other attribution studies for Iran over the past five years have concluded that climate change made heatwaves and droughts over the region more intense and likely.

Meanwhile, the World Meteorological Organization’s (WMO’s) “state of the climate in the Arab region 2024” report warned about the impact of climate change on water security across the region.

In a statement, WMO secretary general Prof Celeste Saulo warned that “droughts are becoming more frequent and severe in one of the world’s most water-stressed regions”.

What other factors are involved?

Climate change is not the only – or even the primary – driver of water scarcity in Iran.

Madani explains:

“We have both the human factors and the climatic factors…A lot of times, local human factors are much more important and significant than the global factors.”

For example, Madani says, the country has experienced large population growth, but its population is concentrated in “a very few large metropolitan” areas, meaning it can struggle to provide enough water to those places. He also points to inefficient agricultural practices and overreliance on technological solutions, including dams and desalination plants.

The vast majority of the country’s water stress comes from its agricultural sector, which accounts for more than 90% of Iran’s water use.

Dr Assem Mayar, an independent researcher focused on water resources and climate security, tells Carbon Brief that Iran’s arid climate means that it uses more water per unit area for cultivating crops than other countries. This issue is compounded by government policies promoting domestic agriculture, he says:

“[Iran’s] government tries to be self-reliant in [the] food sector, which consumes the most share of water in the country.”

Both of the country’s main water sources – surface water and groundwater – are overexploited, Mayar says.

A 2021 study on the drivers of groundwater depletion in Iran found that between 2002 and 2015, Iran’s aquifers were depleted by around 74 cubic kilometres – 1.6 times larger than the amount of water stored in Iran’s largest lake, Lake Urmia, at its highest recorded levels.

The study also found that some basins had experienced depletion rates of up to 2,600% in that timeframe.

Groundwater aquifers naturally “recharge” as water percolates down from the surface. However, a 2023 study also found that this rate of recharge has been declining since the early 2000s.

When groundwater or other resources are extracted from the ground in high quantities, the land above the aquifer can compact and the aquifers themselves can collapse, leading to “subsidence” as the land surface sinks. Iran is one of the countries with the largest subsidence rates in the world, according to a 2024 study.

In late 2025, BBC News reported that Iran had begun “cloud seeding” – injecting salt particles into clouds to promote condensation, in an effort to “combat the country’s worst drought in decades”.

The country has been employing the technique since 2008 and reports that rainfall increased by 15% in the targeted areas as a result.

However, this does little to address the root of the problem, experts tell Carbon Brief.

Prof Nima Shokri, director of the Institute of Geo-Hydroinformatics at Hamburg University of Technology, tells Carbon Brief:

“Iran’s water crisis stems primarily from decades of policy choices that prioritised ideological and geopolitical objectives over sustainable resource management. A costly foreign policy posture and prolonged international isolation have limited access to foreign investment, modern technology and diversified economic development.

“Domestically, this has translated into policies that encouraged groundwater-dependent agriculture, expanded irrigated land without enforceable extraction limits, maintained heavy energy and water subsidies and underinvested in wastewater reuse, leakage reduction and monitoring systems.”

How could attacks on desalination plants impact water supplies in the Middle East?

A pair of attacks on desalination plants has led to significant media speculation around how the conflict might exacerbate freshwater supplies, both in Iran and across the Middle East.

On Saturday 7 March, Iran accused the US of attacking a desalination plant on Qeshm Island in the Strait of Hormuz.

Describing the attack on the critical water infrastructure as “blatant and desperate crime”, foreign minister Seyed Abbas Araghchi said water supply in 30 villages had been impacted.

The next day, Bahrain government said Iran had caused “material damage” to one of its desalination plants during a drone attack.

David Michel, senior fellow for water security at the Centre for Strategic and International Studies, told the Daily Mail that attacks on water plants in Gulf states by Iran could be designed to “impose costs” that push them to intervene or call for the end of the war.

There has been a boom in desalination across the Middle East in recent decades, as water-scarce countries have turned to the technology – which transforms seawater into freshwater – to boost freshwater supplies.

Collectively, the Middle East accounts for roughly 40% of global desalinated water production, producing 29m cubic metres of water every day, according to a 2026 review. This is shown in the chart below.

Iran has more than 163 desalination plants. However, it is less reliant on these plants than smaller countries in the region with fewer water reserves.

In a 2022 policy paper, the Institut Français des Relations Internationales noted Kuwait, Qatar and Oman sourced 90%, 90% and 86% of drinking water from desalination plants, respectively.

In contrast, an official from Iran’s state-run water company told the Tehran Times in 2022 that just 3% of the country’s drinking water came from desalination plants. (Iran’s water supply is sourced primarily from groundwater and rivers and reservoirs.)

Shrokri says the ongoing conflict is “hitting water security” in Iran through “direct and indirect” attacks on critical infrastructure – including desalination plants, power stations and water networks. He adds:

“The conflict is straining an already fragile system inside Iran. The country entered the war with severe drought, depleted groundwater and shrinking reservoirs, so any disruption to energy systems, industrial facilities or supply chains can quickly cascade into water shortages.”

Shokri also highlights that attacks on desalination plants in the Gulf could have serious consequences for major cities – including Dubai, Doha and Abu Dhabi – “rely heavily” on desalinated seawater for drinking water. He says:

“Without desalination plants, large parts of the region’s modern urban system will struggle to exist. The ripple effects would extend far beyond drinking water. Sanitation systems would begin to fail, public health risks would rise and economic activity could slow dramatically.”

Experts have pointed out that attacks on electricity infrastructure could also impact provision of drinking water, given desalination plants are energy-intensive and often co-located with power plants.

Dr Raha Hakimdavar, a hydrologist at Georgetown University, told Al Jazeera that attacks on desalination plants could also impact domestic food production in the long-term, if groundwater is diverted away from agriculture and towards households.

What policies could help Iran avoid a ‘water day zero’?

Experts tell Carbon Brief that the conflict could make chronic water shortages in Iran more likely – even if hostilities are unlikely to directly force a “water day zero”.

Shokri says:

“The war could accelerate the timeline, but it didn’t create the risk of day zero. Iran’s water system was already under extreme pressure from long-term mismanagement and distorted policy priorities. Conflict simply reduces the margin for error.”

Mayar says the war is “unlikely to force day zero nationwide”, but could bring forward “localised day‑zero conditions in already stressed regions”. These effects could be felt most acutely in Iran’s islands and cities that are already “facing chronic shortages”, he continues.

Since agriculture is such a large contributor to the country’s water usage, potential solutions must focus on that sector, experts say.

Mayar says the government should “phase out subsidy policies that encourage overuse”.

In 2018, researchers at Stanford University released a “national adaptation plan for water scarcity in Iran”, as part of a programme looking at the country’s long-term sustainable development.

That report lays out two sets of adaptation actions: those that work to improve the efficiency of water use and those that end water-intensive activities. Among the specific actions recommended by the report are reusing treated wastewater, reducing irrigated farming and enhancing crop-growing productivity through technological solutions.

The adaptation report concludes:

“The underlying solution to address Iran’s water problem is obvious: consumption should be regulated and reduced, water productivity should be improved and wastewater should be treated and reused in the system.”