After agreeing an interim set of rules for how it will operate, the global Fund for Responding to Loss and Damage (FRLD) will next month launch a call for proposals on how to address and repair the destruction caused by climate change.

At a meeting in the Philippines this week, the FRLD’s board decided on how the fund will operate next year, before permanent rules are agreed. In this interim period, it will have at least $250 million to spend and, at November’s COP30 climate summit in Belém, will ask for project proposals it could fund.

The board’s co-chair, South African climate negotiator Richard Sherman, said he expects to adopt the first set of proposals within six months. The fledgling fund – which was set up under the UN climate process – will then ask wealthy governments for more money, through a replenishment process, in 2027.

Elizabeth Thompson, an FRLD board member from the government of Barbados, said she was “happy” to see the fund’s interim rules adopted and hopes they will “spur innovative approaches” to allow countries “access to resources at scale – and that it will be a source of real support against rapid and slow onset climate events”.

“That cannot happen however,” she warned, “unless the fund is filled, as the need and scale of the crisis far outstrip the monies in the fund to date.”

Citing the recent International Court of Justice advisory opinion on climate change, she said that “the countries responsible for the climate crisis need to fund the cost of loss and damage suffered by affected countries – this is now an urgent and legal matter and countries need to accept their responsibility.”

The Independent High-Level Expert Group on Climate Finance has estimated that, by 2030, developing countries could require $200 billion-$400 billion a year to address loss and damage caused by storms, droughts, flooding, extreme heat and rising seas made worse by climate change.

Since the fund was formally agreed two years ago, developed countries have pledged $788 million, signed commitments for over $560 million, and actually transferred less than $400 million of that total.

‘Fill the fund’ campaign

Harjeet Singh, founding director of India’s Satat Sampada Climate Foundation, told a press conference after the FRLD board meeting ended on Thursday that this amount was “absolutely insignificant compared to what is needed by communities and countries”, adding that civil society’s “Fill the Fund” campaign would push developed countries to make new pledges.

Italy is responsible for the biggest chunk of the gap between pledges and cash transfers. At COP28 two years ago, Prime Minister Giorgia Meloni promised €100 million ($115 million) to the fund but has yet to convert the pledge into a formal agreement that sets out how the money will be provided.

“Looking at official documents, the loss and damage fund is not mentioned anywhere,” Caterina Molinari, policy advisor on finance at Italian think-tank Ecco, told Climate Home News. “This is not some spending that Italy is planning to make,” she said, adding “they need to put their money where their mouth is”.

Comment: The ICJ climate ruling has major implications for the loss and damage fund

At this week’s board meeting, government representatives from developed and developing countries were unable to agree on a strategy to mobilise additional resources due to divisions on the role of capital markets and innovative sources of finance – like taxes on first-class plane tickets.

Other areas of disagreement – according to a draft document seen by Climate Home News – include how much funding should be loans versus grants, and how regular fundraising rounds should be. The board now aims to decide this at its board meeting in October 2026.

The post Loss and damage fund will launch call for proposals at COP30 appeared first on Climate Home News.

Loss and damage fund will launch call for proposals at COP30

Climate Change

The Voracious Vine That ‘Ate the South’ Can Also Fuel Wildfires

Brought to the United States as an ornamental porch decoration, the kudzu vine has reshaped itself into ladder fuel for wildfires.

Nearly every Monday morning, five restorationists with Conserving Carolina guide volunteers through the steep hills of Norman Wilder Forest in Tryon, North Carolina. Armed with chainsaws, thick gloves and a pickaxe-like mattock, the group goes hunting for a wily prey: kudzu.

The Voracious Vine That ‘Ate the South’ Can Also Fuel Wildfires

Climate Change

New Jersey’s Balancing Act: Cut Utility Bills Without Derailing Clean Energy

Governor Mikie Sherrill wants to tap clean-energy funds to cushion residents from rising electricity bills.

Halfway through her inaugural speech in front of thousands of New Jerseyans in late January, newly elected governor Mikie Sherrill paused to write her signature on two documents. They were her first two executive orders.

New Jersey’s Balancing Act: Cut Utility Bills Without Derailing Clean Energy

Climate Change

Q&A: What does Trump’s repeal of US ‘endangerment finding’ mean for climate action?

On 12 February, US president Donald Trump revoked the “endangerment finding”, the bedrock of federal climate policy.

The 2009 finding concluded that six key greenhouse gases, including carbon dioxide (CO2), were a threat to human health – triggering a legal requirement to regulate them.

It has been key to the rollout of policies such as federal emission standards for vehicles, power plants, factories and other sources.

Speaking at the White House, US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) administrator Lee Zeldin claimed that the “elimination” of the endangerment finding would save “trillions”.

The revocation is expected to face multiple legal challenges, but, if it succeeds, it is expected to have a “sweeping” impact on federal emissions regulations for many years.

Nevertheless, US emissions are expected to continue falling, albeit at a slower pace.

Carbon Brief takes a look at what the endangerment finding was, how it has shaped US climate policy in the past and what its repeal could mean for action in the future.

- What is the ‘endangerment finding’?

- How has it shaped federal climate policy?

- How is the finding being repealed and will it face legal challenge?

- What does this mean for federal efforts to address climate change?

- What has the reaction been?

- What will the repeal mean for US emissions?

What is the ‘endangerment finding’?

The challenges of passing climate legislation in the US have meant that the federal government has often turned instead to regulations – principally, under the 1970 Clean Air Act.

The act requires the EPA to regulate pollutants, if they are found to pose a danger to public health and the environment.

In a 2007 legal case known as Massachusetts vs EPA, the Supreme Court ruled that greenhouse gases qualify as pollutants under the Clean Air Act. It also directed the EPA to determine whether these gases posed a threat to human health.

The 2009 “endangerment finding” was the result of this process and found that greenhouse gas emissions do indeed pose such a threat. Subsequently, it has underpinned federal emissions regulations for more than 15 years.

In developing the endangerment finding, the EPA pulled together evidence from its own experts, the US National Academies of Sciences, Engineering and Medicine and the wider scientific community.

On 7 December 2009, it concluded that US greenhouse gas emissions “in the atmosphere threaten the public health and welfare of current and future generations”.

In particular, the finding highlighted six “well-mixed” greenhouse gases: carbon dioxide (CO2); methane (CH4); nitrous oxide (N2O); hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs); perfluorocarbons (PFCs); and sulfur hexafluoride (SF6).

A second part of the finding stated that new vehicles contribute to the greenhouse gas pollution that endangers public health and welfare, opening the door to these emissions being regulated.

At the time, the EPA noted that, while the finding itself does not impose any requirements on industry or other entities, “this action was a prerequisite for implementing greenhouse gas emissions standards for vehicles and other sectors”.

On 15 December 2009, the finding was published in the federal register – the official record of US federal legislation – and the final rule came into effect on 14 January 2010.

At the time, then-EPA administrator Lisa Jackson said in a statement:

“This finding confirms that greenhouse gas pollution is a serious problem now and for future generations. Fortunately, it follows President [Barack] Obama’s call for a low-carbon economy and strong leadership in Congress on clean energy and climate legislation.

“This pollution problem has a solution – one that will create millions of green jobs and end our country’s dependence on foreign oil.”

How has it shaped federal climate policy?

The endangerment finding originated from a part of the Clean Air Act regulating emissions from new vehicles and so it was first applied in that sector.

However, it came to underpin greenhouse gas emission regulation across a range of sectors.

In May 2010, shortly after the Obama EPA finalised the finding, it was used to set the country’s first-ever limits on greenhouse gas emissions from light-duty engines in motor vehicles.

The following year, the EPA also released emissions standards for heavy-duty vehicles and engines.

However, findings made under one part of the Clean Air Act can also be applied to other articles of the law. David Widawsky, director of the US programme at the World Resources Institute (WRI), tells Carbon Brief:

“You can take that finding – and that scientific basis and evidence – and apply it in other instances where air pollutants are subject or required to be regulated under the Clean Air Act or other statutes.

“Revoking the endangerment finding then creates a thread that can be pulled out of not just vehicles, but a whole lot of other [sources].”

Since being entered into the federal register, the endangerment finding has also been applied to stationary sources of emissions, such as fossil-fuelled power plants and factories, as well as an expanded range of non-stationary emissions sources, including aviation.

(In fact, the EPA is compelled to regulate emissions of a pollutant – such as CO2 as identified in the endangerment finding – from stationary sources, once it has been regulated anywhere else under the Clean Air Act.)

In 2015, the EPA finalised its guidance on regulating emissions from fossil-fuelled power plants. These performance standards applied to newly constructed plants, as well as those that underwent major modifications.

This ruling noted that “because the EPA is not listing a new source category in this rule, the EPA is not required to make a new endangerment finding…in order to establish standards of performance for the CO2”.

The following year, the agency established rules on methane emissions from oil and gas sources, including wells and processing plants. Again, this was based on the 2009 finding.

The 2016 aircraft endangerment finding also explicitly references the vehicle-emissions endangerment finding. That rule says that the “body of scientific evidence amassed in the record for the 2009 endangerment finding also compellingly supports an endangerment finding” for aircraft.

The endangerment finding has also played a critical role in shaping the trajectory of climate litigation in the US.

In a 2011 case, American Electric Power Co. vs Connecticut, the Supreme Court unanimously found that, because greenhouse gas emissions were already regulated by the EPA under the Clean Air Act, companies could not be sued under federal common law over their greenhouse gas emissions.

Widawsky tells Carbon Brief that repealing the endangerment finding therefore “opens the door” to climate litigation of other kinds:

“When plaintiffs would introduce litigation in federal courts, the answer or the courts would find that EPA is ‘handling it’ and there’s not necessarily a basis for federal litigation. By removing the endangerment finding…it actually opens the door to the question – not necessarily successful litigation – and the courts will make that determination.”

How is the finding being repealed and will it face legal challenge?

The official revocation of the endangerment finding is yet to be posted to the federal register. It will be effective 60 days after the text is published in the journal.

It is set to face no shortage of legal challenges. The state of California has “vowed” to sue, as have a number of environmental groups, including Sierra Club, Earthjustice and the National Resources Defense Council.

Dena Adler, an adjunct professor of law at New York University School of Law, tells Carbon Brief there are “significant legal and analytical vulnerabilities” in the EPA’s ruling. She explains:

“This repeal will only stick if it can survive legal challenge in the courts. But it could take months, if not years, to get a final judicial decision.”

At the heart of the federal agency’s argument is that it claims to lack the authority to regulate greenhouse gas emissions in response to “global climate change concerns” under the Clean Air Act.

In the ruling, the EPA says the section of the Act focused on vehicle emissions is “best read” as authorising the agency to regulate air pollution that harms the public through “local or regional exposure” – for instance, smog or acid rain – but not pollution from “well-mixed” greenhouse gases that, it claims, “impact public health and welfare only indirectly”.

This distinction directly contradicts the landmark 2007 Supreme Court decision in Massachusetts vs EPA. (See: What is the ‘endangerment finding’?)

The EPA’s case also rests on an argument that the agency violated the “major questions doctrine” when it started regulating greenhouse gas emissions from vehicles.

This legal principle holds that federal agencies need explicit authorisation from Congress to press ahead with actions in certain “extraordinary” cases.

In a policy brief in January, legal experts from New York University School of Law’s Institute of Policy Integrity argued that the “major questions doctrine” argument “fails for several reasons”.

Regulating greenhouse gas emissions under the Clean Air Act is “neither unheralded nor transformative” – both of which are needed for the legal principle to apply, the lawyers said.

Furthermore, the policy brief noted that – even if the doctrine were triggered – the Clean Air Act does, in fact, supply the EPA with the “clear authority” required.

Mark Drajem, director of public affairs at NRDC, says the endangerment finding has been “firmly established in the courts”. He tells Carbon Brief:

“In 2007, the Supreme Court directed EPA to look at the science and determine if greenhouse gases pose a risk to human health and welfare. EPA did that in 2009 and federal courts rejected a challenge to that in 2012.

“Since then, the Supreme Court has considered EPA’s greenhouse gas regulations three separate times and never questioned whether it has the authority to regulate greenhouse gases. It has only ruled on how it can regulate that pollution.”

However, experts have noted that the Trump administration is banking on legal challenges making their way to the Supreme Court – and the now conservative-leaning bench then upholding the repeal of the endangerment finding.

Elsewhere, the EPA’s new ruling argues that regulating emissions from vehicles has “no material impact on global climate change concerns…much less the adverse public health or welfare impacts attributed to such global climate trends”.

“Climate impact modelling”, it continues, shows that “even the complete elimination of all greenhouse gas emissions” of vehicles in the US would have impacts that fall “within the standard margin of error” for global temperature and sea level rise.

In this context, it argues, regulations on emissions are “futile”.

(The US is more historically responsible for climate change than any other country. In its 2022 sixth assessment report, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change said that further delaying action to cut emissions would “miss a brief and rapidly closing window of opportunity to secure a liveable and sustainable future for all”.)

However, the final rule stops short of attempting to justify the plans by disputing the scientific basis for climate change.

Notably, the EPA has abandoned plans to rely on the findings of a controversial climate science report commissioned by the Department of Energy (DoE) last year.

This is a marked departure from the draft ruling, published in August, which argued there were “significant questions and ambiguities presented by both the observable realities of the past nearly two decades and the recent findings of the scientific community, including those summarised in the draft CWG [‘climate working group’] report”.

The CWG report – written by five researchers known for rejecting the scientific consensus on human influence on global warming – faced significant criticism for inaccurate conclusions and a flawed review process. (Carbon Brief’s factcheck found more than 100 misleading or false statements in the report.)

A judge ruled in January that the DoE had broken the law when energy secretary Chris Wright “hand-picked five researchers who reject the scientific consensus on climate change to work in secret on a sweeping government report on global warming”, according to the New York Times.

In a press release in July, the EPA said “updated studies and information” set out in the CWG report would serve to “challenge the assumptions” of the 2009 finding.

But, in the footnotes to its final ruling, the EPA notes it is not relying on the report for “any aspect of this final action” in light of “concerns raised by some commenters”.

Legal experts have argued that the pivot away from arguments undermining climate science is designed with future legal battles over the attempted repeal in mind.

What does this mean for federal efforts to address climate change?

As mentioned above, a number of groups have already filed legal actions against the Trump administration’s move to repeal the endangerment finding – leaving the future uncertain.

However, if the repeal does survive legal challenges, it would have far-reaching implications for federal efforts to address greenhouse gas emissions, experts say.

In a blog post, the WRI’s Widawsky said that the repeal would have a “sweeping” impact on federal emissions regulations for cars, coal-fired power stations and gas power plants, adding:

“In practical terms, without the endangerment finding, regulating greenhouse gas emissions is no longer a legal requirement. The science hasn’t changed, but the obligation to act on it has been removed.”

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Widawsky adds that, despite this large immediate impact, there are “a lot of mechanisms” future US administrations might be able to pursue if they wanted to reinstate the federal government’s obligation to address greenhouse gas emissions:

“Probably the most direct way – rather than talk about ‘pollutants’, in general, and the EPA, say, making a science-specific finding for that pollutant – [is] for Congress simply to declare a particular pollutant to be a hazard for human health and welfare. [This] has been done in other instances.”

If federal efforts to address greenhouse gas emissions decline, there will likely still be attempts to regulate at the state level.

Previous analysis from the University of Oxford noted that, despite a walkback on federal climate policy in Trump’s second presidential term, 19 US states – covering nearly half of the country’s population – remain committed to net-zero targets.

Widawksy tells Carbon Brief that it is possible that states may be able to leverage legislation, including the Clean Air Act, to enact regulations to address emissions at the state level.

However, in some cases, states may be prevented from doing so by “preemption”, a US legal doctrine where higher-level federal laws override lower-level state laws, he adds:

“There are a whole lot of other sections of the Clean Air Act that may either inhibit that kind of ability for states to act through preemption or allow for that to happen.”

What has the reaction been?

The Trump administration’s decision has received widespread global condemnation, although it has been celebrated by some right-wing newspapers, politicians and commentators.

In the US, former US president Barack Obama said on Twitter that the move will leave Americans “less safe, less healthy and less able to fight climate change – all so the fossil-fuel industry can make even more money”.

Similarly, California governor Gavin Newsom called the decision “reckless”, arguing that it will lead to “more deadly wildfires, more extreme heat deaths, more climate-driven floods and droughts and greater threats to communities nationwide”.

Former US secretary of state and climate envoy John Kerry called the decision “un-American”, according to a story on the frontpage of the Guardian. He continued:

“[It] takes Orwellian governance to new heights and invites enormous damage to people and property around the world.”

An editorial in the Guardian dubbed the repeal as “just one part of Trump’s assault on environmental controls and promotion of fossil fuels”, but added that it “may be his most consequential”.

Similarly, an editorial in the Hindu said that Trump is “trying to turn back the clock on environmental issues”.

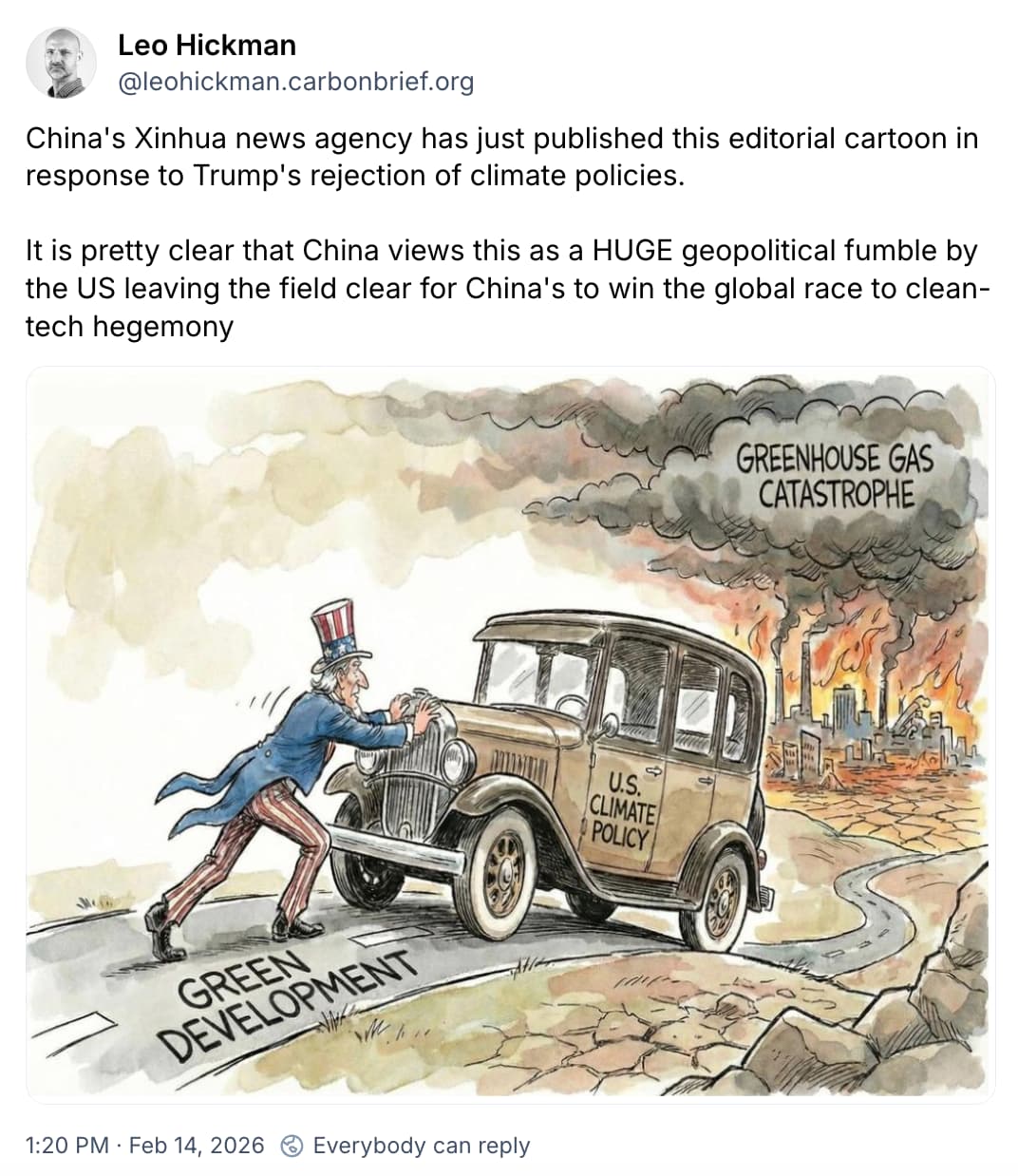

In China, state-run news agency Xinhua published a cartoon depicting Uncle Sam attempting to turn an ageing car, marked “US climate policy”, away from the road marked “green development”, back towards a city engulfed in flames and pollution that swells towards dark clouds labelled “greenhouse gas catastrophe”.

Conversely, Trump described the finding as “the legal foundation for the green new scam”, which he claimed “the Obama and Biden administration used to destroy countless jobs”.

Similarly, Al Jazeera reported that EPA administrator Zeldin said the endangerment finding “led to trillions of dollars in regulations that strangled entire sectors of the US economy, including the American auto industry”. The outlet quoted him saying:

“The Obama and Biden administrations used it to steamroll into existence a left-wing wish list of costly climate policies, electric vehicle mandates and other requirements that assaulted consumer choice and affordability.”

An editorial in the Washington Post also praises the move, saying “it’s about time” that the endangerment finding was revoked. It argued – without evidence – that the benefits of regulating emissions are “modest” and that “free-market-driven innovation has done more to combat climate change than regulatory power grabs like the ‘endangerment finding’ ever did”.

The Heritage Foundation – the climate-sceptic US lobby group that published the influential “Project 2025” document before Trump took office – has also celebrated the decision.

Time reported that the group previously criticised the endangerment finding, saying that it was used to “justify sweeping restrictions on CO2 and other greenhouse gas emissions across the economy, imposing huge costs”. The magazine added that Project 2025 laid out plans to “establish a system, with an appropriate deadline, to update the 2009 endangerment finding”.

Climate scientists have also weighed in on the administration’s repeal efforts. Prof Andrew Dessler, a climate scientist at Texas A&M University in College Station, argued that there is “no legitimate scientific rationale” for the EPA decision.

Similarly, Dr Katharine Hayhoe, chief scientist at the Nature Conservancy, said in a statement that, since the establishment of the 2009 endangerment finding, the evidence showing greenhouse gases pose a threat to human health and the environment “has only grown stronger”.

Dr Gretchen Goldman, president and CEO of the Union of Concerned Scientists and a former White House official, gave a statement, arguing that “ramming through this unlawful, destructive action at the behest of polluters is an obvious example of what happens when a corrupt administration and fossil fuel interests are allowed to run amok”.

In the San Francisco Chronicle, Prof Michael Mann, a climate scientist at the University of Pennsylvania, and Bob Ward, policy and communications director at the Grantham Research Institute, wrote that Trump is “slowing climate progress”, but that “it won’t put a stop to global climate action”. They added:

“The rest of the world is moving on and thanks to Trump’s ridiculous insistence that climate change is a ‘hoax’, the US now stands to lose out in the great economic revolution of the modern era – the clean-energy transition.”

What will the repeal mean for US emissions?

Federal regulations and standards underpinned by the endangerment finding have been at the heart of US government plans to reduce the nation’s emissions.

For example, NRDC analysis of EPA data suggests that Biden-era vehicle standards, combined with other policies to boost electric cars, were set to avoid nearly 8bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent (GtCO2e) over the next three decades.

By removing the legal requirement to regulate greenhouse gases at a federal level from such high-emitting sectors, the EPA could instead be driving higher emissions.

Nevertheless, some climate experts argue that the repeal is more of a “symbolic” action and that EPA regulations have not historically been the main drivers of US emissions cuts.

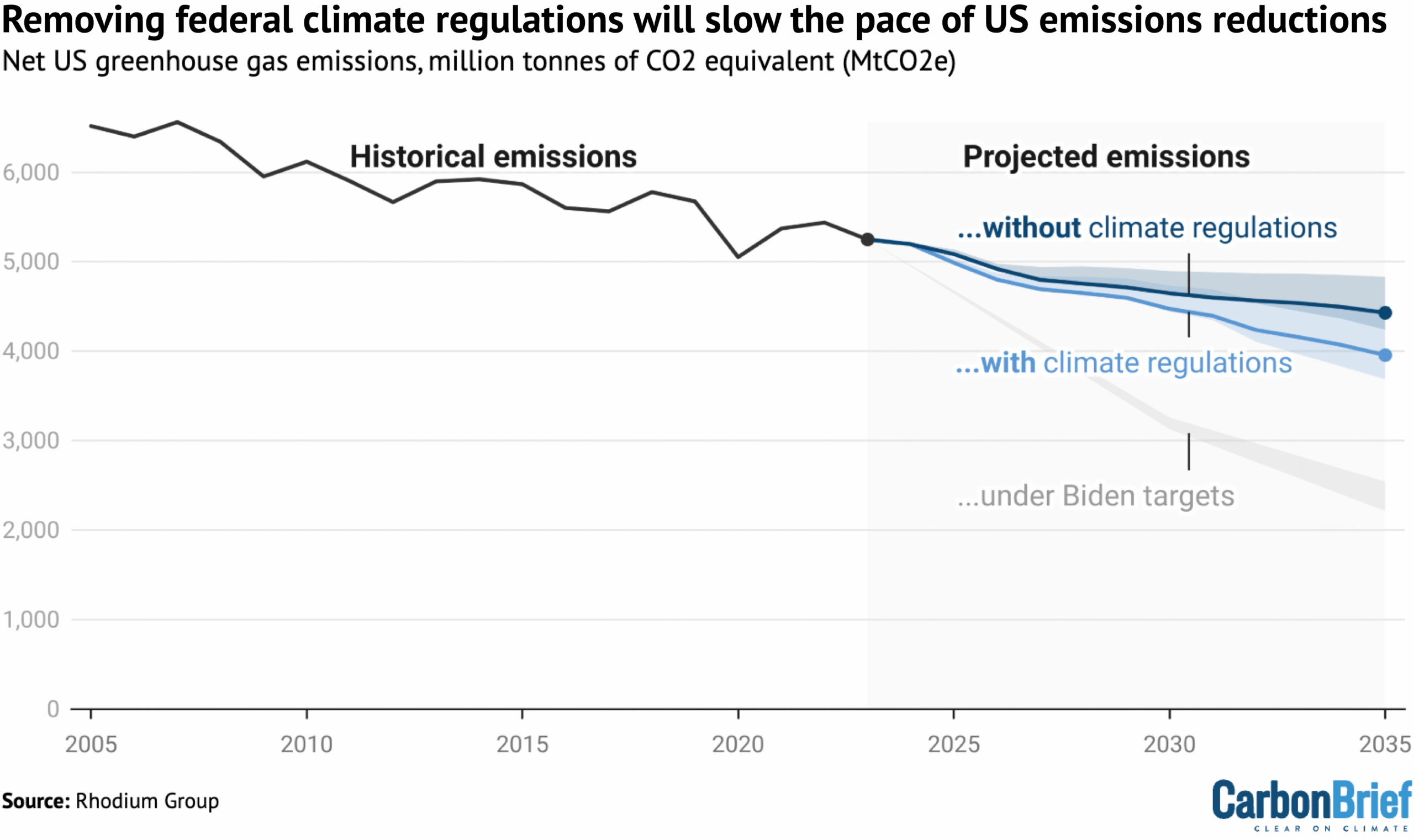

Rhodium Group analysis last year estimated the impact of the EPA removing 31 regulatory policies, including the endangerment finding and “actions that rely on that finding”. Most of these had already been proposed for repeal independently by the Trump administration.

Ben King, the organisation’s climate and energy director, tells Carbon Brief this “has the same effect on the system as repealing the endangerment finding”.

The Rhodium Group concluded that, in this scenario, emissions would continue falling to 26-35% below 2005 levels by 2035, as the chart below shows. If the regulations remained in place, it estimated that emissions would fall faster, by around 32-44%.

(Notably, neither of these scenarios would be in line with the Biden administration’s international climate pledge, which was a 61-66% reduction by 2035).

There are various factors that could contribute to continued – albeit slower – decline in US emissions, in the absence of federal regulations. These include falling costs for clean technologies, higher fossil-fuel prices and state-level legislation.

Despite Trump’s rhetoric, coal plants have become uneconomic to operate in the US compared with cheaper renewables and gas. As a result, Trump has overseen a larger reduction in coal-fired capacity than any other US president.

Meanwhile, in spite of the openly hostile policy environment, relatively low-cost US wind and solar projects are competitive with gas power and are still likely to be built in large numbers.

The vast majority of new US power capacity in recent years has been solar, wind and storage. Around 92% of power projects seeking electricity interconnection in the US are solar, wind and storage, with the remainder nearly all gas.

The broader transition to low-carbon transport is well underway in the US, with electric vehicle sales breaking records during nearly every month in 2025.

This can partly be attributed to federal tax credits, which the Trump administration is now cutting. However, cheaper models, growing consumer preference and state policies are likely to continue strengthening support.

Even if emissions continue on a downward trajectory, repealing the endangerment finding could make it harder to drive more ambitious climate action in the future. Some climate experts also point to the uncertainty of future emissions reductions.

“[It] depends on a number of technology, policy, economic and behavioural factors. Other folks are less sanguine about greenhouse gas declines,” WRI’s Widawsky tells Carbon Brief.

The post Q&A: What does Trump’s repeal of US ‘endangerment finding’ mean for climate action? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: What does Trump’s repeal of US ‘endangerment finding’ mean for climate action?

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits