This is the starting point for Europe’s lofty dreams of greener air travel – a collection point in Malaysia for greasy plastic bottles filled with discarded frying oil, thousands of miles from its final destination.

One Saturday morning last month in the city of Melaka, volunteers in green T-shirts rushed over as Adibah Rahim and her husband drove into the central square, eager to unpack, weigh and register her consignment of used cooking oil (UCO) – the “liquid gold” in European plans to ramp up production of sustainable aviation fuel (SAF).

Rahim left the collection point 90 ringgit ($21) richer, three ringgit per litre of oil – a welcome boost to her family’s household budget.

“We usually collect UCO from around 200 members of the public,” said Michael Andrew, sales manager for Evergreen Oil & Feed, the company running the Melaka collection with the local council and a supplier to leading European SAF producers including Spain’s Repsol, UK-based Shell and Finland’s Neste.

When made from waste such as UCO, rather than agricultural commodities like soy or palm oil, backers say SAF can slash planet-heating emissions by up to 80% over kerosene jet fuel, without taking up land that would otherwise be used for food crops, or fuelling forest destruction.

But behind SAF’s climate-friendly facade, a months-long investigation by Climate Home News and its partner The Straits Times has uncovered an opaque global supply chain that exposes jet fuel providers and their aviation clients to significant fraud risks, raising doubts about the climate benefits of the sector’s main green hope for the years ahead.

As SAF producers scramble for limited raw materials to meet new blending quotas in Europe and growing demand elsewhere, barely used and virgin palm oil is being passed off as UCO to traders that supply fuel companies, experts and industry operators told us. Palm oil that is not considered waste is not permitted under European Union rules for SAF because of its links to deforestation.

Our reporting focused on the UCO trade between Malaysia, the world’s second-biggest palm oil producer, and Spain, the EU’s largest aviation market and home to one of its SAF pioneers – oil-and-gas giant Repsol.

Fried in Spain?

Speaking at the World Economic Forum in Davos in January, Repsol CEO Josu Jon Imaz held up his company’s new 250-million-euro ($285 million) plant for renewable fuels, including SAF, near the historic Spanish port town of Cartagena as an example of how Europe can pursue a fair, green transition. Nearly half of the plant’s cost was financed by the EU’s lending arm, the European Investment Bank.

Repsol, which aims to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, started large-scale production of biodiesel and jet fuel – with its SAF mainly made from UCO – at the plant early last year.

Contrasting this with electric vehicles, many of them imported from China, Imaz said the raw material for Repsol’s renewable fuels “comes from Spanish farms and from the Spanish rural economy”.

In a promotional video for those fuels, Spanish celebrity chef Susi Díaz is seen dispensing advice to young cooks in the kitchen of her La Finca restaurant. Olive oil is then poured out of a pan into steel jugs as a voiceover explains how the waste cooking residue will be sent to the Repsol biofuels refinery.

Spain’s restaurants, however, are not the main source of Repsol’s UCO.

In 2024, more than 126,000 tonnes of UCO from Asia – enough to fill 50 Olympic-sized swimming pools – arrived in the Spanish region of Murcia, where Repsol’s flagship biofuels plant is located, according to trade data published by Spain’s tax agency.

Nearly two-thirds came from Malaysia, whose UCO exports to the region saw a 10-fold rise in the same year the energy heavyweight fired up its Cartagena SAF refinery.

The figures do not specify who provided or bought the raw material. But Climate Home obtained a list of shipments of UCO certified for the European market that were sourced from Malaysia by Repsol’s trading unit in Singapore, based on analysis of customs records provided by Data Desk, an investigative consultancy.

Repsol told Climate Home it “complements with imports when necessary” and receives raw material shipments from more than 20 countries. It declined to provide more details about its imports for “competitive reasons”.

The company is promoting the recycling of UCO from Spanish households – of which it says only 5% is currently collected – at its fuel stations across the country. But according to the trade data, Repsol purchased at least 53,000 tonnes of UCO from five Malaysian companies, including Evergreen Oil & Feed, in 2024.

No incidents involving fraudulent UCO were detected in Repsol’s supply chain, with its imports meeting EU rules on green certification. But our investigation found the company’s heavy reliance on Malaysian supplies exposes it to fraud risks that raise wider questions about global assertions over the sustainability of SAF.

-

Factbox: How we tracked Repsol’s UCO supply chain

Climate Home set out to find out what sustainable aviation fuels (SAF) are made of and how sustainable they really are. We focused on the supply chain of Repsol as the leading fuel supplier in the EU’s largest aviation market and a prominent advocate of SAF as a solution to decarbonising the sector.

Repsol does not publicly disclose detailed information on where the raw materials used in its SAF production are sourced from. A company representative told us that Repsol operates in “a global market, and for competitive reasons, we do not specify the origins or percentages of the raw materials”.

We analysed the summary audit report for the sustainability certificate issued for Repsol’s flagship SAF refinery in Cartagena. The document from International Sustainability and Carbon Certification (ISCC) lists the raw materials used at the plant, but provides only limited information on the origin of each specific feedstock.

We submitted a freedom of information request to the European Commission asking for a detailed list of shipments to Spain of used cooking oil (UCO), which we knew was Repsol’s main feedstock. In response, the Commission sent a highly redacted document obscuring the names of suppliers and recipients. We asked the Commission to review the decision, but after a nine-month wait, its original response was largely upheld.

Spanish authorities had asked for the names to be redacted, arguing that their disclosure would “infringe the legitimate interests” of those concerned, the Commission said.

We then analysed foreign trade records published by Spain’s tax authority. While the data did not include names of individual companies, it pointed to a spike in imports of UCO destined for the Murcia region – where Repsol’s SAF plant is located – from Malaysia and China in 2024.

Working with Data Desk – an investigative consultancy – we obtained a list of Malaysian companies that supplied UCO to Repsol’s trading unit in Singapore. This unit has said publicly that it is “deeply involved” in the supply chain for raw materials – mainly UCO – from Asia for renewable fuels, including SAF.

Having located Repsol’s suppliers, we then sent a reporter to attend a UCO collection event organised by the largest of these, Evergreen Oil & Feed, in the city of Melaka, where its owner confirmed it sells UCO to the Spanish energy giant.

Asked what steps it takes to fight fraud, Repsol said it operates a rigorous supplier monitoring system to ensure the sustainability and integrity of its SAF production. A “very strong” compliance process means dubious raw materials and suppliers suspected of misconduct are quickly weeded out, it added.

“Repsol firmly rejects any fraud that distorts competitiveness in the sector and supports all initiatives by relevant authorities to combat it,” the company said in emailed comments.

Shrinking air travel’s carbon footprint

Europe’s green aviation fuel refineries are boosting output because of new requirements by the EU and the UK for planes to use more SAF in the coming decades. From the start of this year, fuel supplied to airports across Europe needs to contain at least 2% of SAF, with targets rising gradually over the next 15 years, putting huge strain on tight global supplies.

SAF is crucial for shrinking aviation’s carbon footprint, according to industry body the International Air Transport Association (IATA), and is expected to account for 65% of emissions reductions by 2050, when the sector has committed to reaching net zero.

In 2023, emissions from international plane travel accounted for 2.5% of the world’s energy-related carbon emissions. As air travel increases, and other sectors are more easily able to decarbonise, that share is set to grow.

Repsol’s Imaz told financial analysts early last year that emissions-cutting alternatives to SAF – such as restricting short-haul flights – would represent “a drop in the ocean”.

But surging demand for SAF’s feedstock of choice, UCO, and a global certification system based on self-declaration at the start of the supply chain are encouraging fraud that undermines the new fuel’s green credentials.

‘Ridiculous’ collection numbers

This investigation found that by the time Asia-based traders ship UCO supplies overseas to refineries for processing into SAF, guaranteeing their environmental integrity is virtually impossible – despite the certification system on which fuel companies and airlines rely.

A source at a leading Malaysian UCO supplier to companies including Repsol told The Straits Times that some UCO collectors and restaurants are committing fraud by providing oil that does not qualify as used, although it is difficult to prove.

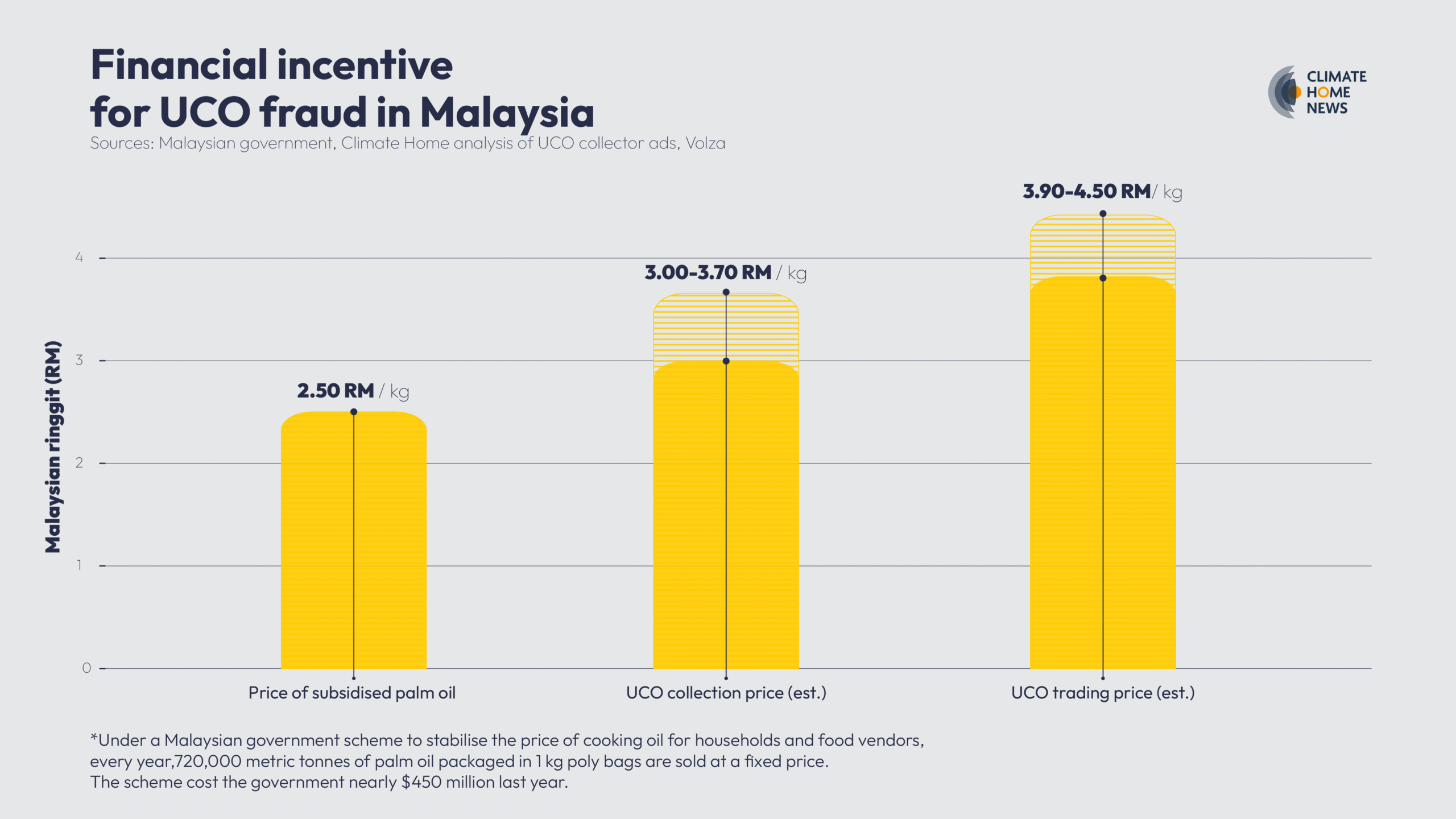

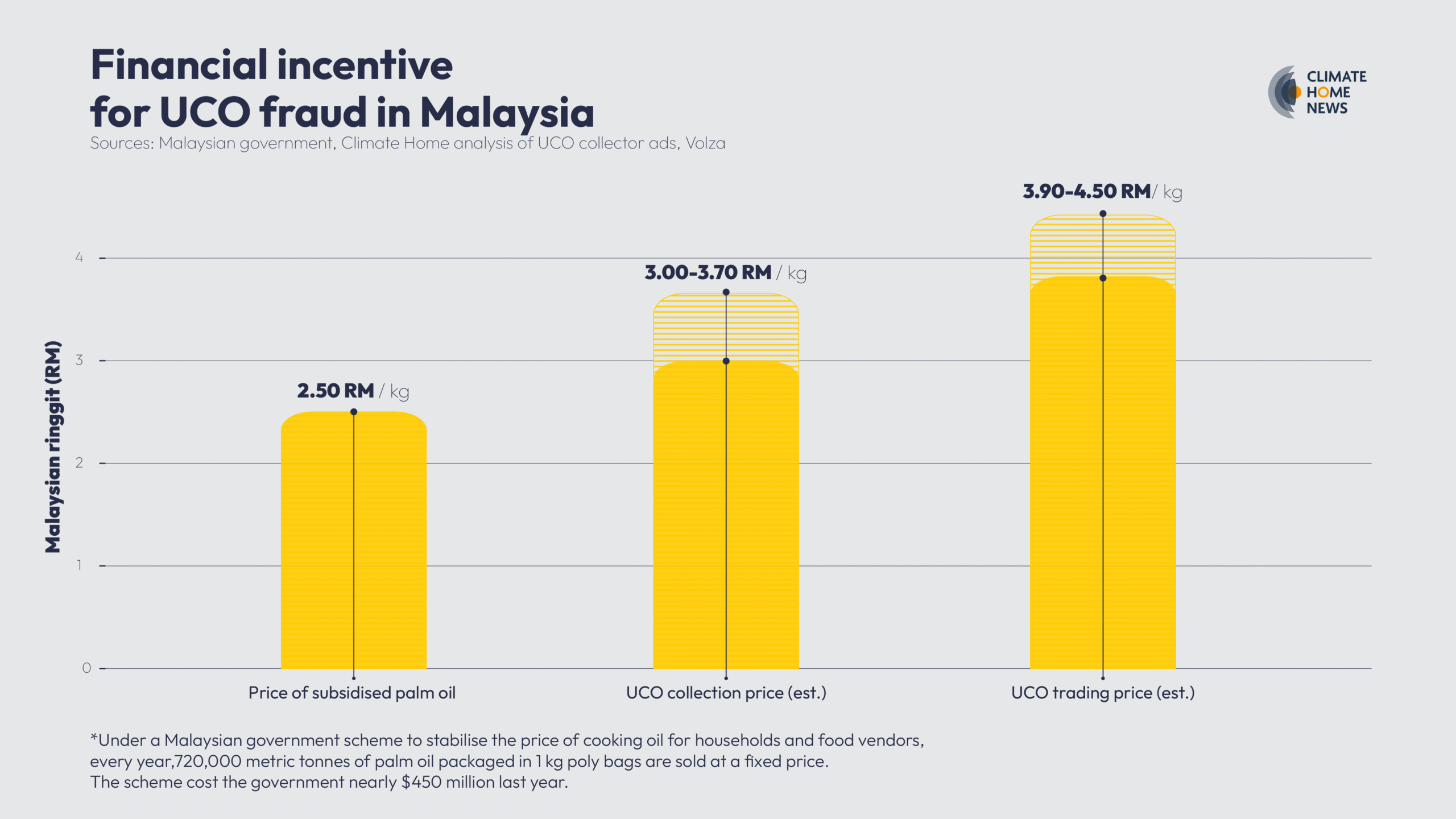

In Malaysia, which is among the world’s leading suppliers of both UCO and virgin palm oil, government-subsidised cooking oil is cheaper than UCO – providing a clear incentive for fraud.

In a 2024 report, Brussels-based environmental group Transport & Environment (T&E) cited figures showing that Malaysia already exports about three times as much UCO as it is estimated to collect domestically and import, raising concern about where that oil is coming from – and what it consists of.

The analysis by consultancy Stratas Advisors, used as a basis for the report, says the “substantial deficit” indicates the “risks of fraud and palm oil potentially compensating for the shortfall”.

In 2023, 458,000 tonnes of UCO originating in Malaysia were registered with International Sustainability and Carbon Certification (ISCC), the leading certification scheme recognised by the European Commission to demonstrate compliance with its biofuels sustainability criteria.

In absolute terms, that puts Malaysia second only to China. But if all that UCO were collected from its population, it would have had by far the highest volumes per person worldwide: 15.2 litres for each Malaysian inhabitant, compared with 0.9 litres per capita in neighbouring Indonesia and 3.8 litres in Spain.

Cian Delaney, campaigns coordinator at T&E, said that figure is “ridiculous”, adding that for it to be feasible, Malaysia would need to be “a world leading collection and refining system – which it isn’t”.

Exactly what it says on the bottle?

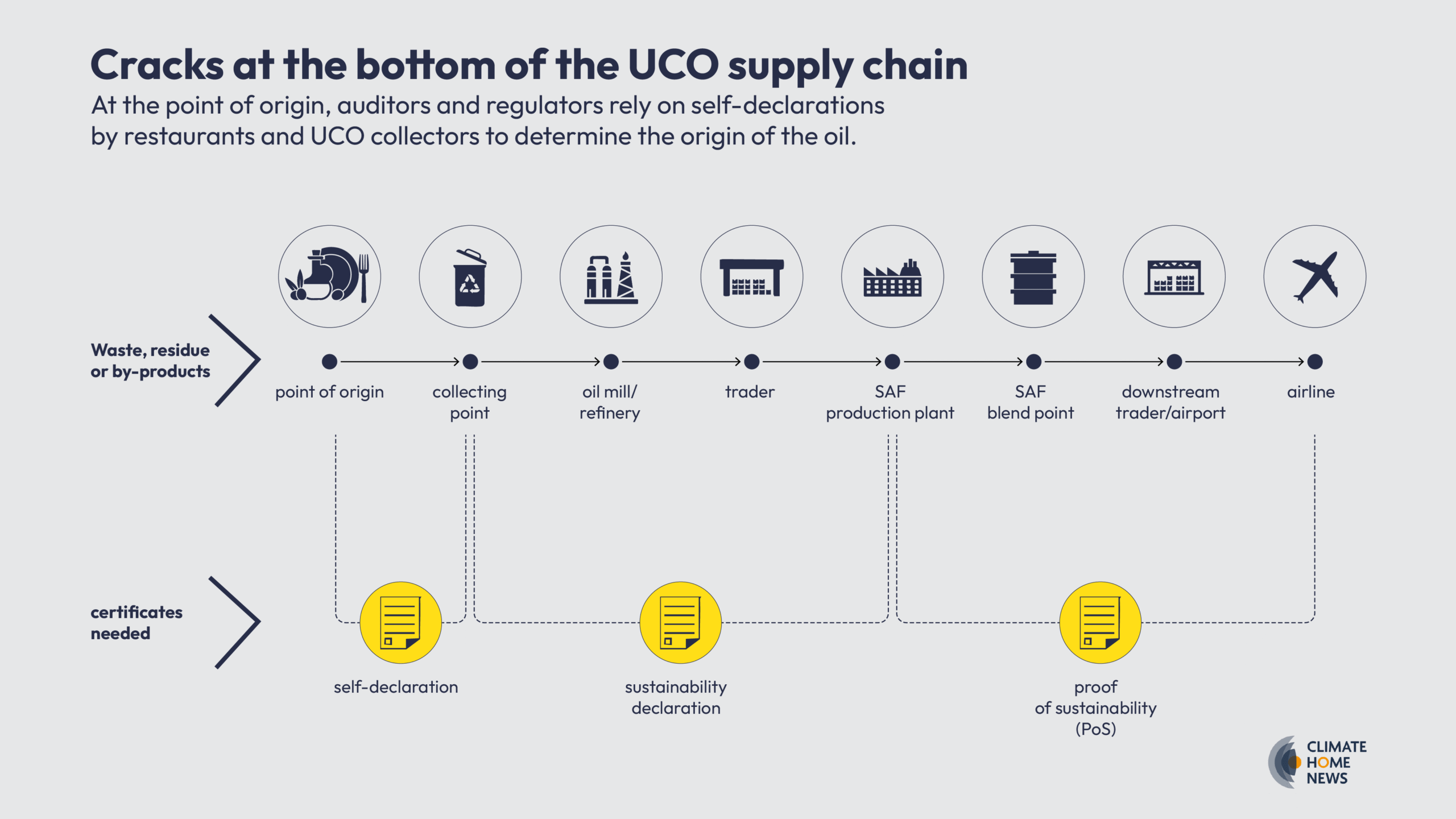

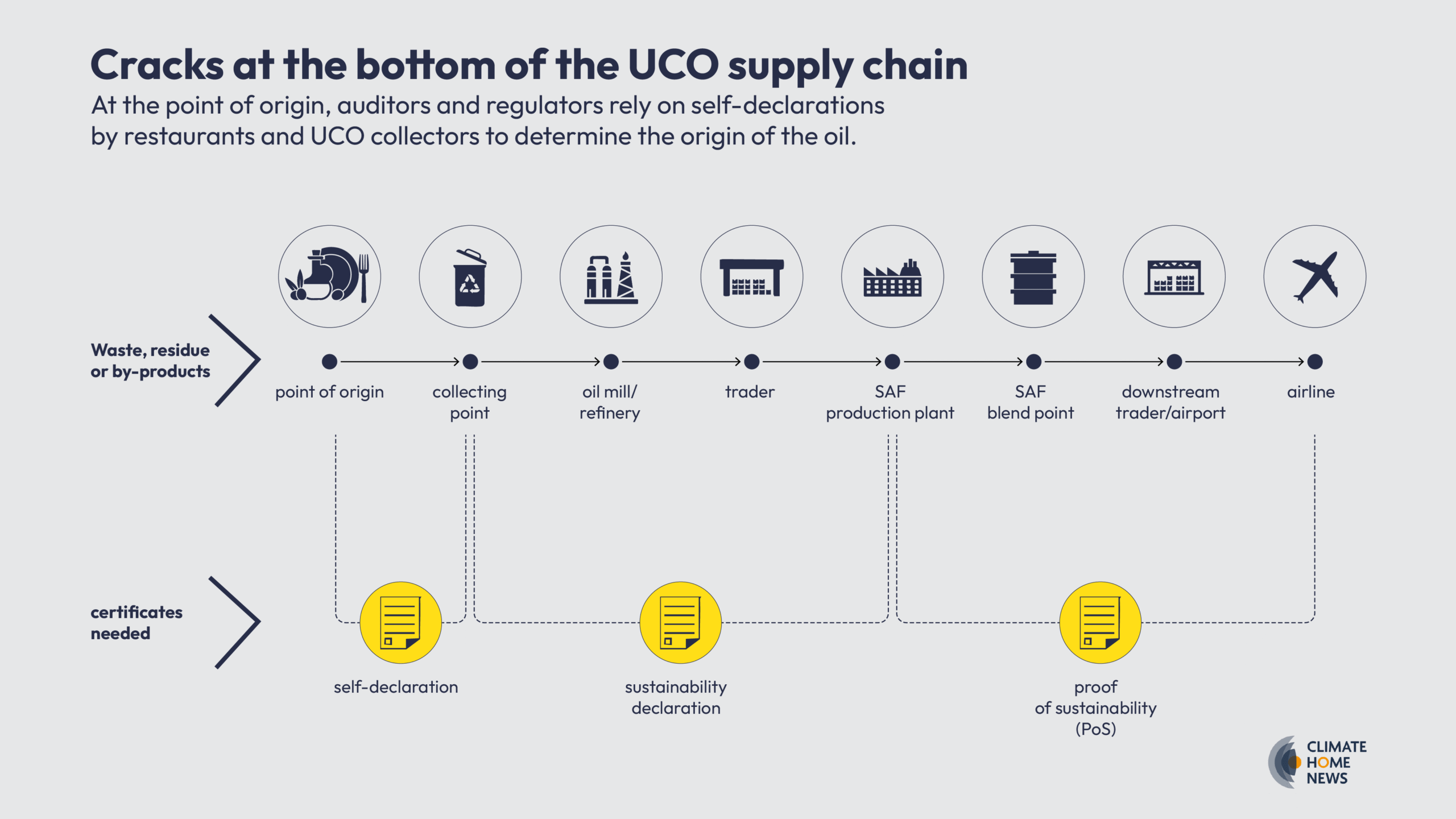

The waste ingredients from which SAF is made change hands multiple times in a largely opaque system. To verify their sustainability, European regulators rely on checks by private auditors and agencies that issue green certificates based on their findings.

But there is a blind spot: the restaurants, street stalls, households and factories from which the UCO is pooled self-declare the origin and authenticity of their contributions. Aside from ad-hoc spot checks and sampling, there is no way of knowing that all of these providers are telling the truth.

“The opportunity, or incidents, of fraud is very high,” said Vasu R Vasuthewan, the former Malaysia head for the ISCC.

Malaysian authorities recently uncovered criminal syndicates that had pocketed thousands of dollars a day by getting hold of large amounts of subsidised cooking oil, mixing it in with UCO, and then selling it on to industrial UCO traders.

Industry sources told Climate Home and The Straits Times that many households and restaurants are motivated to replace cooking oil after a single use – contrary to standard practice – and then sell it on as UCO. Cooking oil is considered waste when it is no longer fit for frying – generally after being used between three and five times.

“Restaurant compliance [with sustainability standards] may be very low,” said Vasuthewan, who now runs his own UCO import and export business. “Many will fake their declaration, hoping they won’t get caught.”

Malaysia’s Deputy Minister of Plantation and Commodities Chan Foong Hin, who has acknowledged that fraud is an issue in the UCO sector, said authorities are “actively monitoring the industry to prevent fraudulent activities” and strengthening enforcement mechanisms.

“To maintain supply chain integrity, various measures are in place, including traceability systems, certification requirements, and stringent export documentation,” he told The Straits Times.

Delaney of T&E said it is difficult for auditors to physically check the origin of the oil, since hundreds of restaurants can supply the same collection point, making it a “notable blind spot”.

Spot checks, patchy audits

In theory, there is a system in place to keep fraudulent stocks out of the supply chain. Buyers and regulators in Europe rely on audit companies to trace the raw materials used in SAF and prove their green credentials.

Those audits are verified by authorised certification systems like ISCC – which is led by the biofuels industry and, according to one source, enjoys “a kind of monopoly” in the sector. It then issues sustainability certificates to commodities traders and fuel suppliers.

ISCC says its certification process supports “sustainable, fully traceable, deforestation-free and climate-friendly supply chains”.

Yet while auditors conduct random field checks in some cases, that happens less often in countries outside the EU, industry experts say.

According to James Cogan, compliance and markets lead at Irish biofuel firm Clonbio, it is far easier for fraud to occur outside the EU where “it’s much less visible to us”.

An analysis by T&E in China, for example, showed that sampling of points of origin happened in less than 10% of the ISCC-approved audits, whereas in the EU it was about 30%.

Adam Kirby, ISCC’s senior sustainability manager, told Climate Home that auditors monitor volumes coming in and out of collection points for any suspicious behaviour, in addition to carrying out spot checks.

He added that the ISCC follows the requirements established by regulators like the European Commission.

-

Factbox: How ISCC verification works

Throughout the complex SAF supply chain, the ISCC requires operators to pass certified information on the origin of the raw materials and their carbon savings from one operator to another.

Traders typically receive UCO from individuals and restaurants at collection points or storage facilities audited under the scheme. But those bringing in the oil are mostly not vetted directly. In the majority of cases, they are simply required to fill out a self-declaration form stating that their UCO meets the definition of waste, meaning that it is not just regular palm oil, and is compliant with the ISCC’s sustainability criteria.

UCO collectors are required to keep all these forms in a database available for inspection by third-party auditors who check that the same amount of UCO coming into a facility is then going out.

If everything stacks up, the ISCC issues a “proof of sustainability” certificate which fuel producers like Repsol rely on to confidently buy the raw material in compliance with EU and/or international regulations.

Airlines are given access to these certificates as evidence they are buying SAF that meets sustainability requirements

In 2024, ISCC also conducted 79 special “integrity assessments” – around two-thirds targeting Asia-based suppliers – which independently monitored the work of auditors. In a third of cases, it found violations of its certification requirements, including an inability to demonstrate the traceability of products, leading to the withdrawal of 11 certificates.

From frying pan to frequent flier

Under the current system, the entire SAF supply chain relies on a long paper trail rooted in those self-declarations and sporadic inspections at the points where UCO is collected.

In Malaysia, Evergreen’s owner CK Lau told The Straits Times the company follows the “proper processes” in its collection based on the requirements established by the ISCC. He added that the documentation is “critical” as, otherwise, the company would not be able to export its UCO.

Repsol, for its part, said it requires “suppliers to be certified under European Commission-recognised voluntary regimes”.

In turn, airline companies that buy from Repsol such as International Airlines Group (IAG) – the parent company of British Airways, Iberia, Vueling, Aer Lingus and LEVEL – rely on documentation they get from it and other jet fuel providers, to show the SAF they are paying for has green certification.

In exceptional cases, IAG told Climate Home it has sent its own staff to carry out checks on the ground, as with a Shanghai-based Chinese supplier last year. It described the outcome of that audit – which included supply, record-keeping, environmental and health and safety standards – as “positive”.

Robert Boyd, Boeing’s Asia-Pacific sustainability lead who previously worked for IATA, thinks airlines’ exacting standards will bring positive change in the SAF industry. “You’ll see a race to the top… on sustainability, and it will, in a way, be self-regulated,” he added.

SAF certification faces EU scrutiny

In the meantime, following a string of fraud allegations about the authenticity of UCO-derived biofuels imported from China, the EU has been trying to ascertain whether the certification system governments and businesses rely on is fit for purpose.

EU authorities have been in talks to strengthen that system, leading to speculation that the ISCC could be suspended for failing to catch cases of biodiesel fraud. The ISCC denied in a statement that regulators had considered halting automatic EU-wide acceptance of its certificates, adding that its relationship with the European Commission remained constructive.

“There’s always bad actors, there’s always bad people, and there’s only a certain amount of policing that can be done in any industry,” said Kirby. “We at ISCC have done, I think, an incredible job.”

A European Commission spokeswoman said the bloc’s executive arm was “closely monitoring” the SAF market “to detect and prevent fraud, which risks undermining the EU’s ambition to effectively decarbonise air transport”.

Authorities in the US and Singapore, which wants to position itself as a regional SAF hub, have also voiced concern about fraud in the SAF supply chain.

“We are aware of concerns raised by various stakeholders, including the EU and the US, regarding fraudulent practices in the SAF supply chain. We share the same concerns as these pose risks to market confidence, fair trading and development of a nascent SAF market,” said Daniel Ng, chief sustainability officer at the Civil Aviation Authority of Singapore (CAAS).

He said the authority was working with the International Civil Aviation Organization’s Committee on Aviation Environmental Protection to develop “harmonised standards for feedstock verification to prevent further fraudulent practices”.

Demand for UCO sizzles

Whatever action regulators take to keep SAF fraud-free, leading European refiners such as Repsol are pushing for a level global playing field as well as more public funding to bring down costs and help develop the nascent sector on the continent.

IATA warned earlier this month that the European mandates had caused the SAF price paid by airlines to double because of hefty compliance fees being charged by producers.

Repsol’s aviation head Carlos Suárez Cubillo warned that fuel producers in parts of the world with laxer rules could produce SAF “with less regulation and less control of the feedstock… and here in Europe that could de-incentivise the production, the construction of new facilities”.

In Brazil, for example, an emerging SAF industry is gearing up to use crop-based feedstocks that are commonly linked to deforestation – and are therefore banned in Europe – such as soy and palm oil, as well as sugarcane-based ethanol, which has been linked to labour abuses and modern slavery.

An investigation by Climate Home’s partner in Brazil, InfoAmazonia, found that the palm oil producer behind a planned biorefinery in the Amazon region – billed as Brazil’s first SAF project – is growing the crop on land areas subject to sanctions by the national environment agency over illegal deforestation, and is struggling financially after rights abuse allegations.

Brazilian firm behind SAF plan found growing oil palm on deforested Amazon land

IATA hopes its efforts to put in place a global registry for SAF, launched in April as a voluntary initiative, will boost transparency around feedstocks and their greenhouse gas savings – and enable airlines to have some level of visibility and comparability between countries, fuel providers and airports.

SAF producers and airlines are also looking to other waste-based materials to meet rising mandates – especially as more advanced fuels made from green hydrogen and carbon dioxide, known as e-SAF, are still being developed and tested.

Air travel’s ‘holy grail’: Jet fuel made from CO2 and water prepares for take-off

Repsol, for example, recently closed a deal with US vegetable oils giant Bunge to source camelina and safflower – non-food crops that can grow on poor land – to produce hydrotreated vegetable oil (HVO) for biodiesel and SAF.

In January, it also announced it would invest more than 800 million euros ($906 million) in Europe’s first plant in the Catalan city of Tarragona to produce “renewable” methanol from organic urban waste that now ends up in landfill, for use in maritime, road and aviation transport from 2029.

But in the meantime, Europe’s overwhelming reliance on UCO means it will continue to import supplies from Asia – despite the concerns over fraud, said Sophie Byron, global head of biofuels pricing at S&P Global Commodity Insights.

“That trade flow is not going away anytime soon,” she said.

‘Token effort’ on aviation emissions?

At Repsol’s vast refinery complex near Cartagena, the colourful pipes and metal cylinders of the flagship SAF unit are dwarfed by the site’s traditional, fossil fuel-refining infrastructure.

Repsol’s plants processed 43.3 million tonnes of crude oil last year, according to its annual report. In contrast, its renewable fuels production capacity stands at 1.25 million tonnes per year – of which the Cartagena plant accounts for 250,000 tonnes, including SAF.

It is a token effort towards tackling rising aviation emissions, said Pedro Luengo of Spanish environmental network Ecologistas en Acción, standing on a hillside overlooking the complex.

As Spain’s airports prepare for another record-breaking summer holiday influx this year, Luengo warned that the hype around SAF could prove counter-productive in the fight against climate change by justifying yet more air travel.

“Instead of gradually substituting fossil fuels with other [green] sources and consuming less, what we are doing is expanding the opportunities because we have more fuels available to use,” he said. “That is a contradiction.”

This investigation was developed with the support of Journalismfund Europe.

The Straits Times in Singapore will publish a version of this story in the coming days.

The post Is the world’s big idea for greener air travel a flight of fancy? appeared first on Climate Home News.

Is the world’s big idea for greener air travel a flight of fancy?

Climate Change

A Tiny Caribbean Island Sued the Netherlands Over Climate Change, and Won

The case shows that climate change is a fundamental human rights violation—and the victory of Bonaire, a Dutch territory, could open the door for similar lawsuits globally.

From our collaborating partner Living on Earth, public radio’s environmental news magazine, an interview by Paloma Beltran with Greenpeace Netherlands campaigner Eefje de Kroon.

A Tiny Caribbean Island Sued the Netherlands Over Climate Change, and Won

Climate Change

Greenpeace organisations to appeal USD $345 million court judgment in Energy Transfer’s intimidation lawsuit

SYDNEY, Saturday 28 February 2026 — Greenpeace International and Greenpeace organisations in the US announce they will seek a new trial and, if necessary, appeal the decision with the North Dakota Supreme Court following a North Dakota District Court judgment today awarding Energy Transfer (ET) USD $345 million.

ET’s SLAPP suit remains a blatant attempt to silence free speech, erase Indigenous leadership of the Standing Rock movement, and punish solidarity with peaceful resistance to the Dakota Access Pipeline. Greenpeace International will also continue to seek damages for ET’s bullying lawsuits under EU anti-SLAPP legislation in the Netherlands.

Mads Christensen, Greenpeace International Executive Director said: “Energy Transfer’s attempts to silence us are failing. Greenpeace International will continue to resist intimidation tactics. We will not be silenced. We will only get louder, joining our voices to those of our allies all around the world against the corporate polluters and billionaire oligarchs who prioritise profits over people and the planet.

“With hard-won freedoms under threat and the climate crisis accelerating, the stakes of this legal fight couldn’t be higher. Through appeals in the US and Greenpeace International’s groundbreaking anti-SLAPP case in the Netherlands, we are exploring every option to hold Energy Transfer accountable for multiple abusive lawsuits and show all power-hungry bullies that their attacks will only result in a stronger people-powered movement.”

The Court’s final judgment today rejects some of the jury verdict delivered in March 2025, but still awards hundreds of millions of dollars to ET without a sound basis in law. The Greenpeace defendants will continue to press their arguments that the US Constitution does not allow liability here, that ET did not present evidence to support its claims, that the Court admitted inflammatory and irrelevant evidence at trial and excluded other evidence supporting the defense, and that the jury pool in Mandan could not be impartial.[1][2]

ET’s back-to-back lawsuits against Greenpeace International and the US organisations Greenpeace USA (Greenpeace Inc.) and Greenpeace Fund are clear-cut examples of SLAPPs — lawsuits attempting to bury nonprofits and activists in legal fees, push them towards bankruptcy and ultimately silence dissent.[3] Greenpeace International, which is based in the Netherlands, is pursuing justice in Europe, with a suit against ET under Dutch law and the European Union’s new anti-SLAPP directive, a landmark test of the new legislation which could help set a powerful precedent against corporate bullying.[4]

Kate Smolski, Program Director at Greenpeace Australia Pacific, said: “This is part of a worrying trend globally: fossil fuel corporations are increasingly using litigation to attack and silence ordinary people and groups using the law to challenge their polluting operations — and we’re not immune to these tactics here in Australia.

“Rulings like this have a chilling effect on democracy and public interest litigation — we must unite against these silencing tactics as bad for Australians and bad for our democracy. Our movement is stronger than any corporate bully, and grows even stronger when under attack.”

Energy Transfer’s SLAPPs are part of a wave of abusive lawsuits filed by Big Oil companies like Shell, Total, and ENI against Greenpeace entities in recent years.[3] A couple of these cases have been successfully stopped in their tracks. This includes Greenpeace France successfully defeating TotalEnergies’ SLAPP on 28 March 2024, and Greenpeace UK and Greenpeace International forcing Shell to back down from its SLAPP on 10 December 2024.

-ENDS-

Images available in Greenpeace Media Library

Notes:

[1] The judgment entered by North Dakota District Court Judge Gion follows a jury verdict finding Greenpeace entities liable for more than US$660 million on March 19, 2025. Judge Gion subsequently threw out several items from the jury’s verdict, reducing the total damages to approximately US$345 million.

[2] Public statements from the independent Trial Monitoring Committee

[3] Energy Transfer’s first lawsuit was filed in federal court in 2017 under the RICO Act – the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations Act, a US federal statute designed to prosecute mob activity. The case was dismissed in 2019, with the judge stating the evidence fell “far short” of what was needed to establish a RICO enterprise. The federal court did not decide on Energy Transfer’s claims based on state law, so Energy Transfer promptly filed a new case in a North Dakota state court with these and other state law claims.

[4] Greenpeace International sent a Notice of Liability to Energy Transfer on 23 July 2024, informing the pipeline giant of Greenpeace International’s intention to bring an anti-SLAPP lawsuit against the company in a Dutch Court. After Energy Transfer declined to accept liability on multiple occasions (September 2024, December 2024), Greenpeace International initiated the first test of the European Union’s anti-SLAPP Directive on 11 February 2025 by filing a lawsuit in Dutch court against Energy Transfer. The case was officially registered in the docket of the Court of Amsterdam on 2 July, 2025. Greenpeace International seeks to recover all damages and costs it has suffered as a result of Energy Transfers’s back-to-back, abusive lawsuits demanding hundreds of millions of dollars from Greenpeace International and the Greenpeace organisations in the US. The next hearing in the Court of Amsterdam is scheduled for 16 April, 2026.

Media contact:

Kate O’Callaghan on 0406 231 892 or kate.ocallaghan@greenpeace.org

Climate Change

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

The Trump administration’s relentless rollback of public health and environmental protections has allowed widespread toxic exposures to flourish, warn experts who helped implement safeguards now under assault.

In a new report that outlines a dozen high-risk pollutants given new life thanks to weakened, delayed or rescinded regulations, the Environmental Protection Network, a nonprofit, nonpartisan group of hundreds of former Environmental Protection Agency staff, warns that the EPA under President Donald Trump has abandoned the agency’s core mission of protecting people and the environment from preventable toxic exposures.

Former EPA Staff Detail Expanding Pollution Risks Under Trump

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits