Last year, China started construction on an estimated 95 gigawatts (GW) of new coal power capacity, enough to power the entire UK twice over.

It accounted for 93% of new global coal-power construction in 2024.

The boom appears to contradict China’s climate commitments and its pledge to “strictly control” new coal power.

The fact that China already has significant underused coal power capacity and is adding enough clean energy to cover rising electricity demand also calls the necessity of the buildout into question.

Furthermore, so much new coal capacity provides an easy counterargument for claims that China is serious about the energy transition.

Did China really need more coal power?

And now that it is here, do all these brand-new power plants mean China’s greenhouse gas emissions will remain elevated for longer?

This article addresses four common talking points surrounding China’s ongoing coal-power expansion, explaining how and why the current wave of new projects might come to an end.

New coal is not needed for energy security

The explanation for China’s recent coal boom lies in a combination of policy priorities, institutional incentives and system-level mismatches, with origins in the widespread power shortages China experienced in the early 2020s.

In 2021, a “mismatch” between the price of coal and the government-set price of coal-fired power incentivised coal-fired power plants to cut generation. Furthermore, power shortages in 2020 and 2022 revealed issues of inflexible grid management and limited availability of power plants, when demand spiked due to extreme weather and elevated energy-intensive economic activity, compounded by coal shortages, reduced hydro output and insufficient imported electricity import.

Following this, energy security became a top priority for the central government. Local governments responded by approving new coal-power projects as a form of insurance against future outages.

Yet, on paper, China had – and still has – more than enough “dispatchable” resources to meet even the highest demand peaks. (Dispatchable sources include coal, gas, nuclear and hydropower.) It also has more than enough underutilised coal-power capacity to meet potential demand growth.

A bigger factor behind the shortages was grid inflexibility. During both the 2020 power crisis in north-east China and the 2022 shortage in Sichuan, affected provinces continued to export electricity while experiencing local shortages.

A lack of coordination between provinces and inflexible market mechanisms governing the “dispatch” of power plants – the instructions to adjust generation up or down – meant that existing resources could not be fully utilised.

Nevertheless, with coal power plants cheap to build and quick to gain approval, many provinces saw them as a reliable way to reassure policymakers, balance local grids and support industry interests, regardless of whether the plants would end up being economically viable or frequently used.

China’s average utilisation rate of coal power plants in 2024 was around 50%, meaning total coal-fired electricity generation could rise substantially without the need for any new capacity.

At the same time as adding new coal, the Chinese government also addressed energy security through improvements to grid operation and market reforms, as well as building more storage.

The country added dozens of gigawatts of battery storage, accelerated pumped hydro projects and improved trading linkages between electricity markets in different provinces.

Though these investments could have gone further, they have already helped avoid blackouts during recent summers – when few of the newly-permitted coal power plants had come online. As such, it is not clear that the new coal plants were needed to guarantee security of supply in the first place.

President Xi Jinping has stated that “energy security depends on developing new energy” – using the Chinese term for renewables excluding hydropower and sometimes including nuclear. According to the International Energy Agency, in the long run, resilience will come not from overbuilding coal, but from modernising China’s power system.

New coal power plants do not mean more coal use and higher emissions

It may seem intuitive to imagine that if a country is building new coal power plants, it will automatically burn more coal and increase its emissions.

But adding capacity does not necessarily translate into higher generation or emissions, particularly while the growth of clean energy is still accelerating.

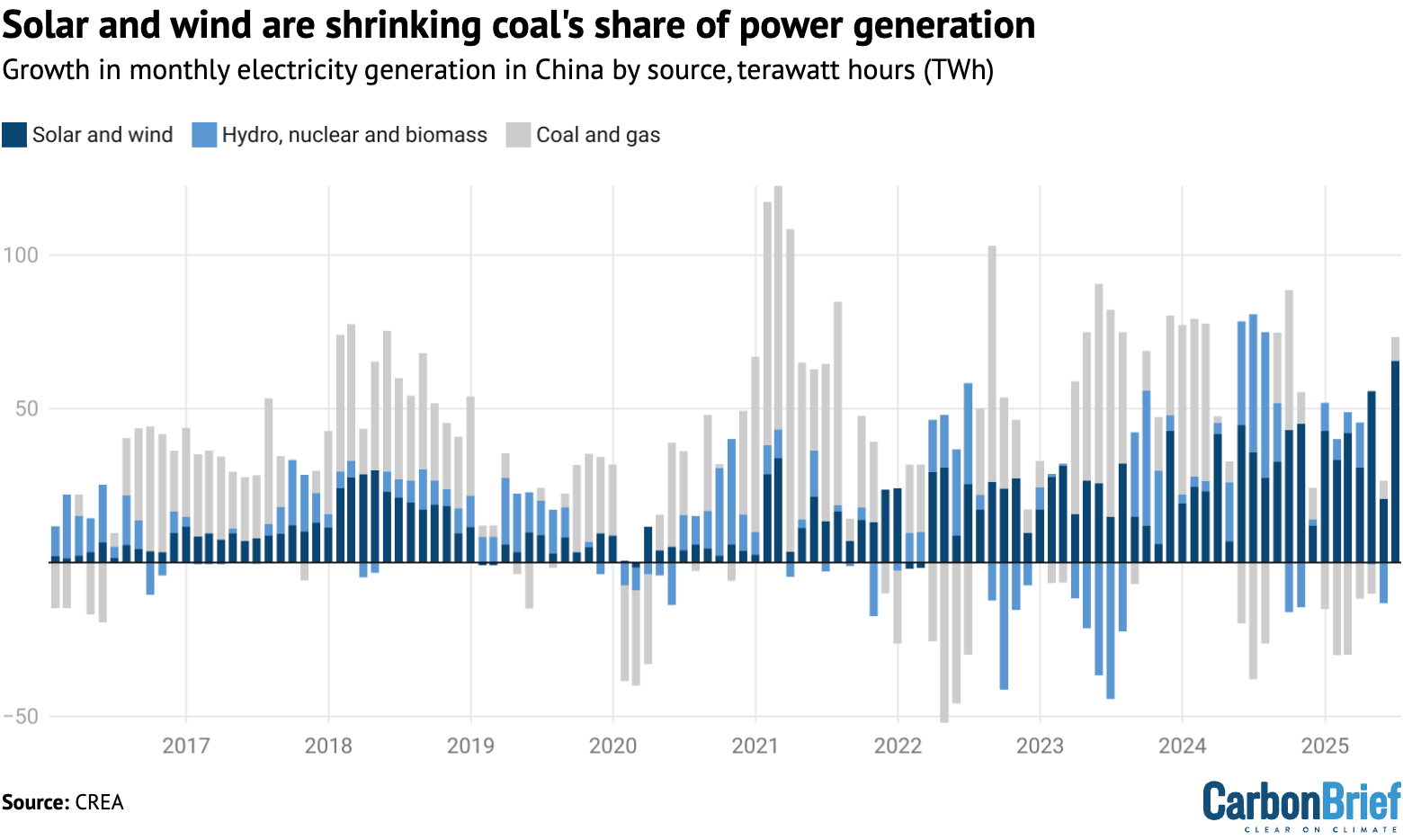

Coal power generation plays a residual role in China’s power system, filling the gap between the power generated from clean energy sources – such as wind, solar, hydro and nuclear – and total electricity demand. As clean-energy generation is growing rapidly, the space left for coal to fill is shrinking.

From December 2024, coal power generation declined for five straight months before ticking up slightly in May and June, mainly to offset weaker hydropower generation due to drought. Coal power generation was flat overall in the second quarter of 2025.

The chart below shows growth in monthly power generation for coal and gas (grey), solar and wind (dark blue) and other low-carbon power sources (light blue).

This illustrates how the rise in wind and solar growth is squeezing the residual demand left for coal power, resulting in declining coal-power output during much of 2025 to date.

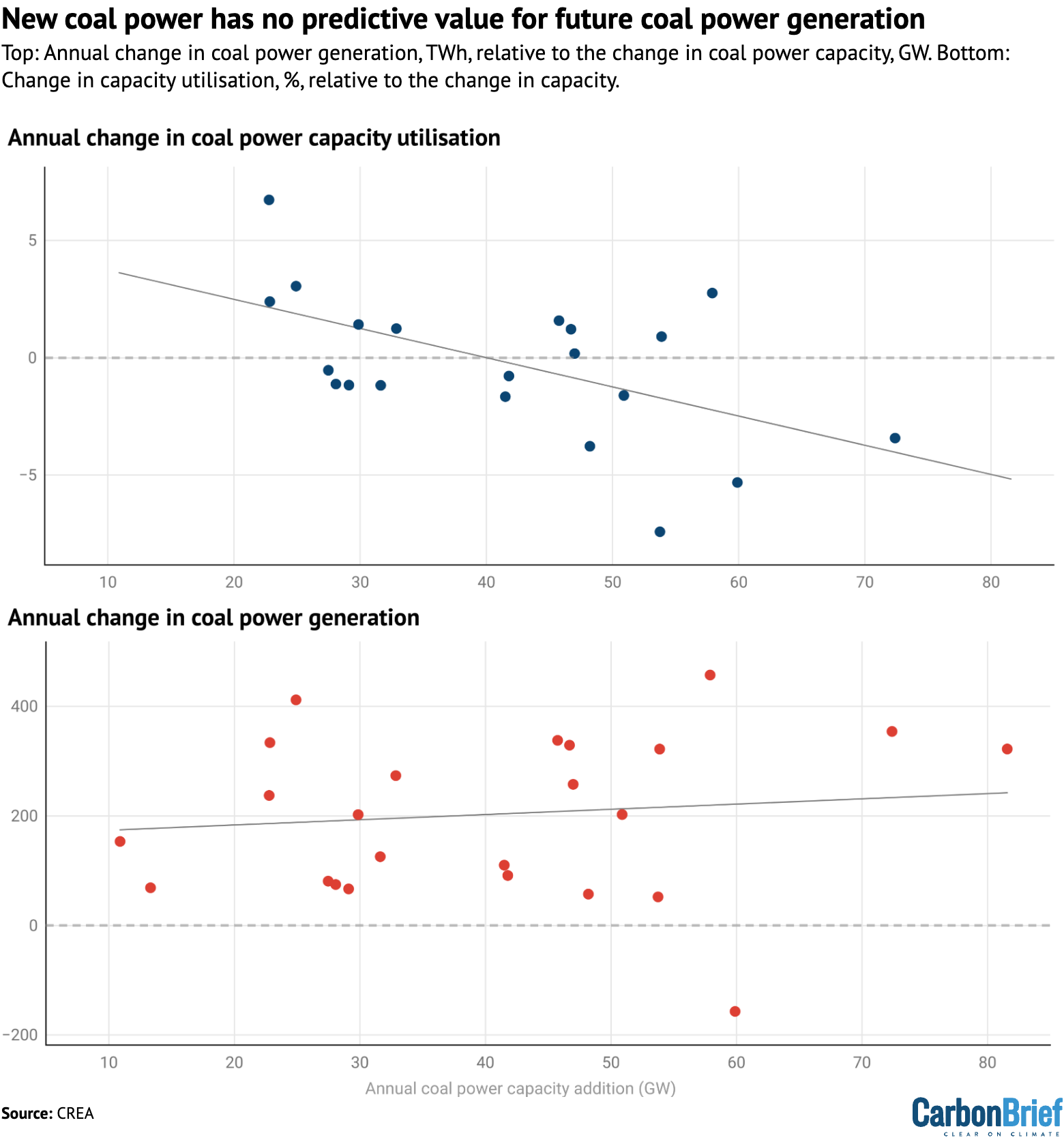

Another way to consider the impact of new coal-fired capacity is to test whether, in reality, it automatically leads to a rise in coal-fired electricity generation.

The top panel in the figure below shows the annual increase in coal power capacity on the horizontal axis, relative to the change in coal-power output on the vertical axis.

For example, in 2023, China added 47GW of new coal capacity and coal power output rose by 3.4TWh. In contrast, only 28GW was added in 2021, yet output still rose by 4.4TWh.

In other words, there is no correlation between the amount of new coal capacity and the change in electricity generation from coal, or the associated emissions, on an annual basis.

Indeed, the lower panel in the figure shows that larger additions of coal capacity are often followed by falling utilisation. This means that adding coal plants tends to mean that the coal fleet overall is simply used less often.

As such, while adding new coal plants might complicate the energy transition and may increase the risk of unnecessary greenhouse gas emissions, an increase in coal use is far from guaranteed.

If instead, clean energy is covering all new demand – as it has been recently – then building new coal plants simply means that the coal fleet will be increasingly underutilised, which poses a threat to plant profitability.

China is not unique in its approach to coal power

The dynamics behind last year’s surge in coal power project construction starts speak to the logic of China’s system, in which cost-efficiency is not always a central concern when ensuring that key problems are solved.

If a combination of three tools – coal power plants, storage and grid flexibility, in this case – can solve a problem more reliably than one alone, then China is likely to deploy all three, even at the risk of overcapacity.

This approach reflects not just a desire for reliability, but also deeper institutional dynamics that help to explain why coal power continues to be built.

But that does not mean that such a pattern is unique to China.

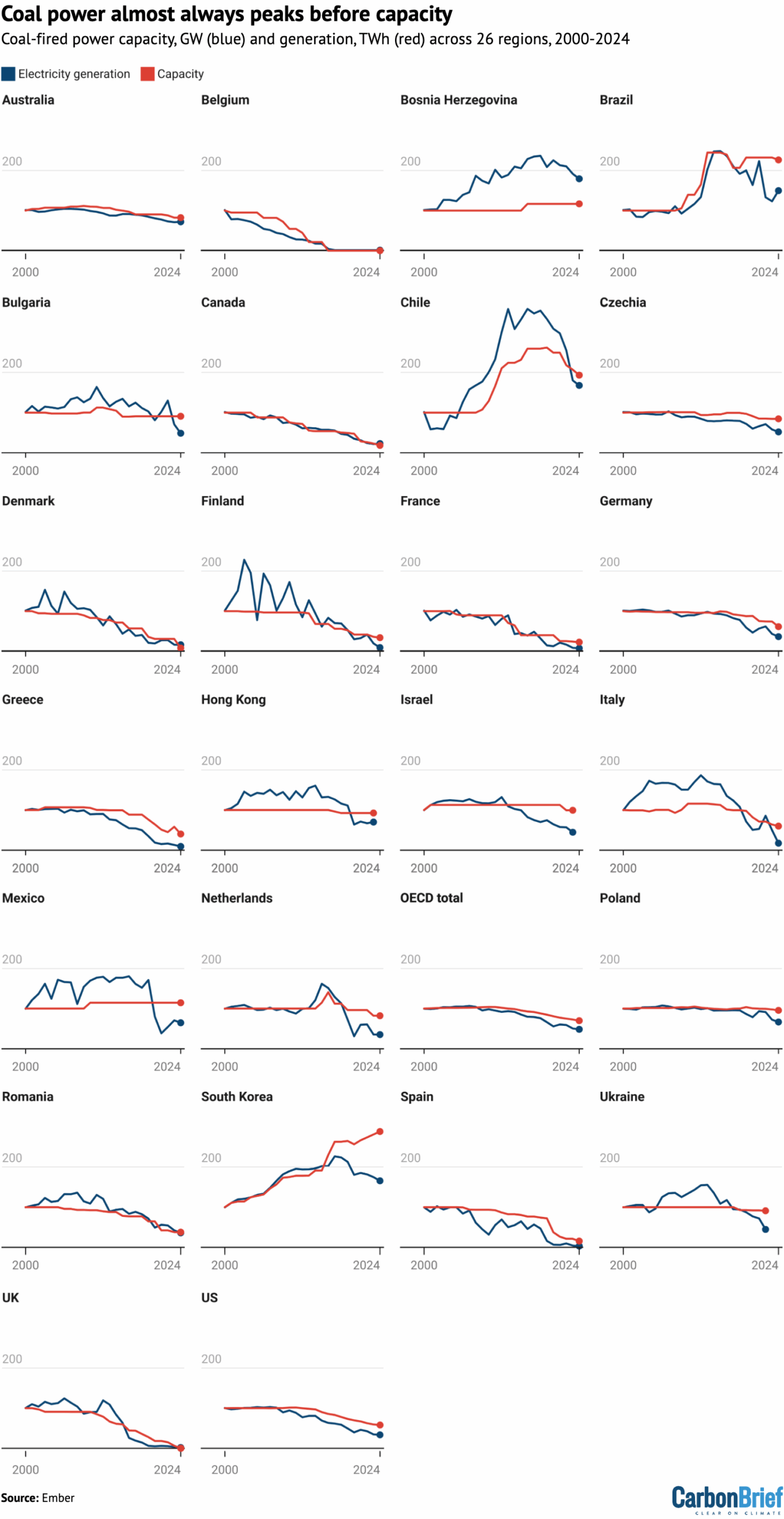

The figure below shows that, across 26 regions, a peak in coal-fired electricity generation (blue lines) almost always comes before coal power capacity (red) starts to decline.

Moreover, the data suggests that once there has been a peak, generation falls much more sharply than capacity, implying that remaining coal plants are kept on the system even as they are used increasingly infrequently.

In most cases, what ultimately stopped new coal power projects in those countries was not a formal ban, but the market reality that they were no longer needed once lower-carbon technologies and efficiency gains began to cover demand growth.

Coal phase-out policies have tended to reinforce these shifts, rather than initiating them. In China, the same market signals are emerging: clean energy is now meeting all incremental demand and coal power generation has, as a result, started to decline.

Coal is not yet playing a flexible ‘supporting’ role

Since 2022, China’s energy policy has stated that new coal-power projects should serve a “supporting” or “regulating” role, helping integrate variable renewables and respond to demand fluctuations, rather than operating as always-on “baseload” generators.

More broadly, China’s energy strategy also calls for coal power to gradually shift away from a dominant baseload role toward a more flexible, supporting function.

These shifts have, however, mostly happened on paper. Coal power overall remains dominant in China’s power mix and largely inflexible in how it is dispatched.

The 2022 policy provided local governments with a new rationale for building coal power, but many of the new plants are still designed and operated as inflexible baseload units. Long-term contracts and guaranteed operating hours often support these plants to run frequently, undermining the idea that they are just backups.

Old coal plants also continue to operate under traditional baseload assumptions. Despite policies promoting retrofits to improve flexibility, coal power remains structurally rigid.

Technical limitations, long-term contracts and economic incentives continue to prevent meaningful change. Coal is unlikely to shift into the flexible supporting role that China says it wants without deeper reform to dispatch rules, pricing mechanisms and contract structures.

Despite all this, China is seeing a clear shift away from coal. Clean-energy installations have surged, while power demand growth has moderated.

As a result, coal power’s share in the electricity mix has steadily declined, dropping from around 73% in 2016 to 51% in June 2025. The chart below shows the monthly power generation share of coal (dark grey), gas (light grey), solar and wind (dark blue), and other low-carbon sources (light blue) from 2016 to the present.

When will the coal boom end?

About a decade ago, the end of China’s coal power expansion also looked near. Coal power plant utilisation declined sharply in the mid-2010s as overcapacity worsened. In response, the government began restricting new project approvals in 2016.

With new construction slowing and power demand rebounding, especially during and after the height of the Covid-19 pandemic, utilisation rates recovered. Not long after, power shortages kicked off the recent coal building spree.

Now, there are new signs that the coal power boom is approaching its end. Permitting is becoming more selective again in some regions, especially in eastern provinces where demand growth is slowing and clean energy is surging. Meanwhile, system flexibility is advancing.

Compared to the late 2010s, the current shift appears more structural. It is driven by the rapid expansion of clean energy, which increasingly eliminates the need for large-scale new coal power projects.

Still, the pace of change will depend on how quickly institutions adapt. If grid operators become confident that peak loads can reliably be met with renewables and flexible backup, the rationale for new coal power plants will weaken.

Equally important, entrenched interests at the provincial and corporate levels continue to push for new plants, not just as insurance, but as sources of investment, employment and revenue. Through long-term contracts and utilisation guarantees, this represents institutional lock-in that may delay the shift away from coal.

The next major turning point will come when coal power utilisation rates begin to fall more sharply and persistently. With large amounts of capacity set to come online in the next two years and clean energy steadily displacing coal in the power mix, a sharp drop in coal power plant utilisation appears likely.

Once this happens, the central government might be expected to step in through administrative capacity cuts – forcing the oldest plants to retire – just as it did during overcapacity campaigns in the steel, cement and coal sectors around 2016 and 2017.

In that sense, China’s coal power phase-out may not begin with a single grand policy declaration, but with a familiar pattern of centralised control and managed retrenchment.

A key question is how quickly institutional incentives and grid operation will catch up with the dawning reality of coal being squeezed by renewable growth, as well as whether they will allow clean energy to lead, or continue to be held back by the legacy of coal.

The upcoming 15th five-year plan presents a crucial test of government priorities in this area. If it wants to bring policy back in line with its long-term climate and energy goals, then it could consider including clear, measurable targets for phasing down coal consumption and limiting new capacity, for example.

While China’s coal power construction boom looks, at first glance, like a resurgence,it currently appears more likely to be the final surge before a long downturn. The expansion has added friction and complexity to China’s energy transition, but it has not reversed it.

The post Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

Climate Change

“We are still here” – COP30 shows resolve to keep fighting climate crisis

COP30 came to a close on Saturday afternoon in the Amazon city of Belém with government delegates grumpy and exhausted after all-night talks. It ended with a political deal that was weaker than many had hoped for and which failed to tackle – or even directly mention – the elephant in the room: fossil fuels.

Strong resistance from oil, coal and gas-producing countries, including Saudi Arabia, Russia and India, made it impossible to include a roadmap to transition away from fossil fuels – which European nations had fought for hard – in the final negotiated package. Brazil, instead, said it would create one, along with another roadmap on halting deforestation.

There were some wins – not least that against a hostile geopolitical background, this year’s UN climate conference managed to land a deal with modest steps towards increasing ambition on cutting emissions and helping poor countries cope with worsening climate impacts.

COP30 fails to land deal on fossil fuel transition but triples finance for climate adaptation

At this weekend’s G20 summit, where the US was also absent, leaders of the world’s biggest economies confirmed their support for the Paris Agreement and efforts to limit global warming to its temperature goals, as well as enabling the Global South to access more finance for climate action.

In one of the few political wins from COP30, the poorest countries secured a promise to triple international funding for them to adapt to more extreme weather and rising seas by 2035, though that deadline was five years later than they wanted and lacking a firm number.

Perhaps the most celebrated result, however – slipping largely under the radar – was an agreement to set up a “just transition mechanism” to ensure that workers and their communities do not lose out from the shift from dirty to clean energy and get a fairer share of the benefits.

Trade was another new kid on the block, with governments deciding to hold a series of dialogues on cooperating “to promote a supportive and open international economic system that would lead to sustainable economic growth and development” in all countries.

Here’s a selection of reactions from top politicians, UN officials, experts and campaigners to the COP30 outcome:

Marina Silva, Brazil’s Minister of the Environment and Climate Change:

“I believe we can show today that, despite delays, contradictions and disputes, there is continuity between the ambition of Rio-92 and today’s effort. That we remain capable of cooperating, of learning, and of recognising that there are no shortcuts – and that the courage to confront the climate crisis is the result of persistence and collective effort.

“But even if those earlier versions of us were to say we have not gone as far as we once imagined we would – or needed to – they would nevertheless recognise something essential: we are still here. And we continue steadfast in our commitment to undertake the journey necessary to overcome our differences and contradictions in urgently confronting climate change.”

Juan Carlos Monterrey-Gomez, Special Representative for Climate Change & National Climate Change Director of the Ministry of Environment of Panama:

“Ten years after the adoption of the Paris Agreement, the negotiators that your governments sent to COP30 are not defending your future. They are defending the very industries that created this crisis: the fossil fuel industry and the forces driving global deforestation…

“A Forest COP with no commitment on forests is a very bad joke. A climate decision that cannot even say “fossil fuels” is not neutrality, it is complicity. And what is happening here transcends incompetence.”

António Guterres, Secretary-General of the United Nations:

“COPs are consensus-based – and in a period of geopolitical divides, consensus is ever harder to reach. I cannot pretend that COP30 has delivered everything that is needed.

“COP30 is over, but our work is not. I will continue pushing for higher ambition and greater solidarity. To all those who marched, negotiated, advised, reported and mobilised: do not give up. History is on your side – and so is the United Nations.”

Al Gore, former US Vice President:

“Despite petrostates’ attempt to veto the development of a roadmap away from fossil fuels, the Brazilian COP30 Presidency will lead an effort to develop this roadmap, bolstered by the more than 80 countries that already support the effort. Ultimately, petrostates, the fossil fuel industry, and their allies are losing power…

“The rest of the world is fed up with delay and denial. Now is the time to forge global partnerships among all levels of government, the private sector, finance, and civil society to cultivate and achieve the level of action necessary to fulfill the promise the world made to future generations under the Paris Agreement.”

Inger Andersen, United Nations Environment Programme Executive Director:

“COP30… reinforced the growing global momentum, both in and outside of the negotiating halls, to transition away from fossil fuels as agreed in Dubai at COP28, halt deforestation – including the launch of the Tropical Forest Forever Facility that now stands at US$6.7 billion – and pursue rapid, high-impact measures such as cutting methane emissions.

“The Action Agenda, the foundation to such an inclusive COP from the Brazil Presidency that saw unprecedented Indigenous Peoples leadership from the Amazon and across the world, reinforced momentum is coming from all sources, including businesses, cities and regions, local communities, civil society, women, people of African descent, youth, and many more.”

Toya Manchineri, Manchineri Peoples, Coordination of Indigenous Organizations of the Brazilian Amazon (COIAB):

“Indigenous Peoples will remain vigilant, mobilised, and present beyond COP30 to ensure that our voices are respected and that global decisions reflect the urgency we experience in our territories. For some, COP ends today, for us territorial defense in the heart of the Amazon is every day.”

Kaysie Brown, Associate Director, Climate Diplomacy & Geopolitics, E3G:

“In an increasingly turbulent and multi-polar world, COP30 was a litmus test of whether political will and commitment to multilateralism could keep pace with the momentum already evident in the real economy.

“A deal was always going to be hard-fought, and the outcome on the table shows that Parties were not consistently resolute in pursuing the level of collective ambition required. Even so, there are important foundations to build on – elements that can be translated into tangible acceleration of real-world progress.”

Li Shuo, Director of the China Climate Hub at the Asia Society Policy Institute:

“COP30 marks a new inflection point in global climate politics. As national climate ambition slows, international negotiations are now constrained by diminishing political will. When the United States steps back, others are left cautious and indecisive.

“Belém has laid bare an urgent truth: in the absence of strong political momentum for greater ambition, the climate agenda will be driven less by the COP process and more by the economic forces unfolding in the real world.”

Mohamed Adow, Director, Power Shift Africa:

“With an increasingly fractured geopolitical backdrop, COP30 gave us some baby steps in the right direction, but considering the scale of the climate crisis, it has failed to rise to the occasion.

“Among the green shoots to emerge was the creation of a Just Transition Action Mechanism – a recognition that the global move away from fossil fuels will not abandon workers and frontline communities.

“COP30 kept the process alive — but process alone will not cool the planet. Roadmaps and workplans will mean nothing unless they now translate into real finance and real action for the countries bearing the brunt of the crisis.”

Tasneem Essop, Executive Director, Climate Action Network International:

“We came here to get the Belém Action Mechanism – for families, for workers, for communities. The adoption of a Just Transition mechanism was a win shaped by years of pressure from civil society.

“This outcome didn’t fall from the sky; it was carved out through struggle, persistence, and the moral clarity of those living on the frontlines of climate breakdown. Governments must now honour this Just Transition mechanism with real action. Anything less is a betrayal of people – and of the Paris promise.”

Ani Dasgupta, President & CEO, World Resources Institute:

“COP30 delivered breakthroughs to triple adaptation finance, protect the world’s forests and elevate the voices of Indigenous people like never before. This shows that even against a challenging geopolitical backdrop, international climate cooperation can still deliver results…

“COP30 succeeded in putting people at the center of climate action. Indigenous Peoples participated in record numbers and made their voices heard. The Global Ethical Stocktake affirmed that fairness, inclusion, and responsibility must guide every decision. New commitments for Indigenous Peoples’ and communities’ land rights and finance offer a strong step forward, though far more is needed.”

The post “We are still here” – COP30 shows resolve to keep fighting climate crisis appeared first on Climate Home News.

“We are still here” – COP30 shows resolve to keep fighting climate crisis

Climate Change

COP30: Key outcomes agreed at the UN climate talks in Belém

A voluntary plan to curb fossil fuels, a goal to triple adaptation finance and new efforts to “strengthen” climate targets have been launched at the COP30 climate summit in Brazil.

After all-night negotiations in the Amazonian city of Belém, the Brazilian presidency released a final package termed the “global mutirão” – a name meaning “collective efforts”.

It was an attempt to draw together controversial issues that had divided the fortnight of talks, including finance, trade policies and meeting the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C temperature goal.

A “mechanism” to help ensure a “just transition” globally and a set of measures to track climate-adaptation efforts were also among COP30’s notable outcomes.

Scores of nations that had backed plans to “transition away” from fossil fuels and “reverse deforestation” instead accepted COP30 president André Corrêa do Lago’s compromise proposal of “roadmaps” outside the formal UN regime.

Billed as a COP of “truth” and “implementation”, the event – which took place 10 years on from the Paris Agreement – was seen as a moment to showcase international cooperation.

Yet, the lack of consensus on key issues and rising salience of “unilateral trade measures” and financial shortfalls revealed deep divisions.

The event itself also faced numerous logistical challenges, including a lengthy delay to negotiations when a fire broke out, forcing thousands of attendees to evacuate.

Here, Carbon Brief provides in-depth analysis of all the key outcomes in Belém – both inside and outside the COP.

(See Carbon Brief’s coverage of COP29, COP28, COP27, COP26, COP25, COP24, COP23, COP22, COP21 and COP20.)

Formal negotiations

Brazilian leadership

Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva first made his bid to host an “Amazon COP” at COP27 in Egypt in 2022, fresh from an election victory.

Speaking in front of a cheering crowd, he laid out a vision for reversing deforestation in Brazil and hosting a rainforest COP in 2025, telling delegates:

“I advocate in a very strong way that the conference should be held in the Amazon.”

Lula faced no challenges from other countries and, at COP28 in Dubai in 2023, it was formally confirmed that Brazil would host COP30, representing the Latin American and Caribbean Group (GRULAC).

Lula’s insistence that COP should take place in the Amazon left only a few viable host city options, including Manaus, the capital of Amazonas state, and Belém, capital of Pará state.

Though Manaus offered some advantages, such as having its own stadium built for the World Cup in 2014, Lula opted for Belém – with some suggesting the decision was linked to Pará state governor, Helder Barbadlho, being a key ally of Lula’s Workers’ party.

After Belém was chosen, concerns were immediately raised that the city would not have enough accommodation for COP30’s 56,000 registered delegates.

In February, Lula caused consternation when, according to Folha de São Paulo, he responded to the fears by saying:

“If you don’t have a four-star hotel, sleep in a three-star hotel. If you don’t have a three-star hotel, sleep [under the] stars in the sky, which will be wonderful…They have to know how much a carapanã [a common mosquito in the Amazon] bite hurts.”

Though rumours swirled that the conference would have to be relocated to Rio de Janeiro, preparations in Belém continued, with the number of available rooms increasing from 18,000 to 36,000 from January to May, according to Brasil de Fato.

In August, just three months before COP30, the Brazilian government launched the summit’s accommodation booking platform, following pressure to do so from a UN committee, Climate Home News reported.

Despite this, “markups and sky-high prices remained”, raising worries that delegates from developing countries would not be able to afford to access the talks, it added.

Just days before the talks began, the COP30 presidency attempted to address concerns by offering free cabins on cruise ships to delegates from African countries, small island states and the least-developed countries (LDCs) group, Reuters said.

The environmental credentials of Lula’s government also came under scrutiny in the run up to the talks.

In August, Lula signed into law what many called the “devastation bill” for its impact on Brazil’s environmental licensing structure, after it was approved by the nation’s largely opposition-led congress, Sumaúma reported.

Just weeks before the talks, Lula’s government approved new oil and gas drilling at the mouth of the Amazon river, drawing condemnation from environmental groups, Mongabay said.

Unusually for a COP, the two-day “high level segment” – where world leaders give speeches with their views and plans on climate change – took place before the summit’s official opening from 6-7 November.

The COP30 presidency said this was to allow more time to rally action – and to avoid the summit’s accommodation crisis.

Reflecting a difficult geopolitical situation heading into COP30, the leaders of China, the US and India – the “planet’s three biggest polluters” – were “notably absent” from the leaders summit, reported the Associated Press.

Lula used his speech at the event to call for “roadmaps” away from deforestation and fossil fuels – he later repeated this in his speech during COP30’s opening. (His call sparked a movement of countries to push for roadmaps in Belém. (See: Fossil-fuel roadmap and deforestation.)

André Corrêa do Lago – a Brazilian economist, diplomat and former climate negotiator – was appointed the president of COP30. (He is the first former negotiator to take up this position.)

Ahead of the opening plenary on the summit’s first day, his team managed to avoid a time-consuming “agenda fight” by telling parties that the presidency would hold consultations on four items some blocs had sought to add to the agenda. These “big four” were on trade measures, climate finance, ambitions to keep global warming to 1.5C and data transparency.

Corrêa do Lago said that the presidency consultations would be followed by a special “stocktaking plenary” on Wednesday, where it would be decided how to take the discussions forward.

Proceedings were disrupted on Tuesday evening, when dozens of Indigenous protesters forced their way into COP’s “blue zone”, leading to clashes with security staff who sustained minor injuries, Reuters said. The protesters were expressing anger at a lack of access to the negotiations, according to the newswire.

The breach prompted UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC) executive secretary, Simon Stiell, to write to both the COP30 presidency and the Brazilian government, to raise concerns about the “wellbeing of delegates and personnel”, Bloomberg reported.

Along with security concerns, Stiell said that delegates had been facing dangerously high temperatures due to faulty air conditioning units, in addition to water leakages and flooding inside the venue, the publication said. The presidency responded by promising to resolve all issues as quickly as possible.

At a press conference on Wednesday afternoon in the first week, COP30 strategy director Túlio Andrade gave an update on the presidency consultations for the additional items on trade measures, climate finance, 1.5C and transparency.

He said that seven hours of consultations had been held and stated that parties had been working together in a manner not witnessed in a “long, long time”.

Alongside him, Corrêa do Lago promised that the stocktaking plenary, scheduled for later that day, would bring “good news” for all, and agreed that the consultations had been “super constructive”.

However, when the plenary began just a few hours later, it ended abruptly, with Corrêa do Lago announcing that more consultations were needed and that the meeting would be rescheduled for Saturday.

As days passed with few new updates, some delegates theorised that the additional items would most likely be taken forward by some kind of “cover text” – an overarching political document that COP presidencies can choose to introduce, to summarise key negotiated outcomes, along with issues not on the official agenda.

However, Corrêa do Lago refused to be drawn on the possibility of a cover text in daily press conferences.

He also largely batted away questions about whether the outcome would include a reference to a “fossil-fuel roadmap” – as called for by Lula and a growing number of developed and developing countries at the summit.

On Thursday, the presidency announced the ministerial pairs of developed and developing nations that would steer key topics in the second week of negotiations.

This included the UK and Kenya on finance, Norway and UAE on the “global stocktake”, Germany and Gambia on adaptation, Spain and Egypt on mitigation, as well as Poland and Mexico on just transition.

On Saturday evening, Corrêa do Lago held the stocktaking plenary session, where he said the presidency consultations had been “rich with ideas”.

The following night, he then published a five-page “summary note”, which listed various options for how the discussions could be taken forward.

One of the possible outcomes listed was a “mutirão decision”, widely interpreted as a possible overarching text containing the key agreements from COP30.

On Monday afternoon, Corrêa do Lago held a muddled press conference, where he floated the possibility of “two packages” coming out of the summit: a “political package” covering the “big four” themes in consultations and another on negotiated tracks, plus other items.

After Corrêa do Lago rushed out to resume meetings, COP30 CEO Ana Toni became the first in the presidency to make an open reference to a “cover text”.

The presidency later followed up with a letter clarifying its position that it was looking to pursue an overall “Belém political package”, rather than a cover text.

The letter added that the presidency hoped to “complete a significant part of our work by tomorrow [Tuesday] evening, so that a plenary to gavel the Belém political package may take place by the middle of the week”.

The idea of finding agreement on the summit’s key text several days before the COP was scheduled to finish was something that had never been achieved before at international climate talks.

In the end, an early deal failed to materialise.

‘Global mutirão’

COP30 saw countries agree to a new “global mutirão” decision, a text calling for a tripling of adaptation finance by 2035 (later than some hoped), a new “Belem mission” to increase collective actions to cut emissions and – to the disappoint of many countries – no new “roadmaps” on transitioning away from fossil fuels and reversing deforestation.

(See Carbon Brief’s snap analysis and further detail in: Adaptation; Ambition and 1.5C, “Unilateral trade measures”; Fossil-fuel roadmap; and Deforestation.)

The first draft “global mutirão” text appeared during the summit’s second week, in the early hours of Tuesday morning.

“Mutirão” is a Portuguese word originating in the Indigenous Tupi-Guarani language that refers to people working together towards a common aim with a community spirit – something the COP30 presidency was keen to emphasise.

The presidency was also keen to stress that the mutirão text was not a cover text (sometimes referred to as a “cover decision”). However, like a cover text, it sought to bring together important issues that were not on the formal agenda with negotiated targets, acting as the key agreement from COP30.

The first draft drew together the “big four” issues of finance, trade, transparency and ambition.

For most of the major elements, the first draft listed various options.

For example, paragraph 56 listed three different options for how developed countries might triple spending on adaptation finance, while paragraph 35 floated three options for a possible “roadmap” away from fossil fuels, including one that simply said “no text”.

The first draft drew immediate condemnation from a group of 82 nations that wanted to see a more ambitious and certain call for a fossil-fuel “roadmap” included in the mutirão.

However, COP30 CEO Ana Toni told a press conference attended by Carbon Brief later that day that a “great majority” of country groups they had consulted saw a fossil-fuel roadmap as a “red line”. (A list of such countries was never made public.)

Lula returned to Belém on Wednesday and – as hopes of an early deal evaporated – he spent his time conducting bilateral meetings with delegations from different negotiating groups with the hope of moving negotiations forward.

Despite negotiations running late into the night on Wednesday, no new mutirão texts emerged by Thursday.

At around 2pm on Thursday, a major fire broke out in the Africa pavilion inside the COP venue, with large orange flames engulfing the surrounding area and burning a hole through the roof. The fire sent delegates in the pavilions area running for the exits.

The COP30 presidency and UNFCCC put out a joint statement saying the fire was extinguished within six minutes, all delegates were evacuated safely and 13 people were treated for smoke inhalation.

Pará state governor Helder Barbalho told local news outlet G1 that a generator failure or a short circuit in the pavilion may have started the fire, NPR reported.

(Carbon Brief understands there was also a fire in the green zone in the first week of the summit, also caused by an electrical fault.)

The fire temporarily put the negotiations on pause, but they were able to resume after 8pm on Thursday night, organisers said.

Early on Friday morning, a long-awaited second version of the draft “mutirão” text emerged.

This text called “for efforts to triple adaptation finance” by 2030, a presidency-led “Belém mission to 1.5C” and a voluntary “implementation accelerator”, as well as a series of “dialogues” on trade.

It did not refer to a “fossil-fuel roadmap”, sparking condemnation from some countries and campaigners. (See: Fossil-fuel roadmap.)

With different countries still poles apart on key issues in the mutirão, negotiations dragged all through Friday.

At one point on Friday afternoon, talks had “descended into turmoil”, as the presidency tried to move discussions into three “huddles” on trade, adaptation finance and ambition, according to several observers speaking to Carbon Brief.

Many countries objected to the lack of a huddle on fossil fuels, while Saudi Arabia said the idea of targeting the energy sector was “off the table”, the observers told Carbon Brief.

After a break, talks resumed, with four huddles being formed, including one on fossil fuels.

During the night, as tensions were rising, UK special climate envoy Rachel Kyte posted on LinkedIn saying that “ministers and negotiators are clutched in huddles, trying to negotiate with each other as opposed to having everything mediated through the Brazilian presidency”.

Speaking to a group of journalists on Saturday morning, EU climate commissioner Wopke Hoekstra described it as a “difficult and intense evening”.

At 10am, the presidency sent an email to delegates saying a new text would soon be circulated and that a closing plenary would follow.

The final version of the mutirão text emerged, “calling for” a tripling of adaptation finance, but with no clear baseline year and a target date of 2035, five years later than an earlier draft. It also contained no fossil-fuel roadmap. (See: Adaptation.)

At a closing plenary, the text was adopted with no objections.

After brief applause, Corrêa do Lago acknowledged that some countries were hoping for “more ambitious” outcomes from the text.

He then announced that the COP30 presidency would bring forward two roadmaps, on transitioning away from fossil fuels and deforestation, to present at the next COP.

He added that the fossil-fuel roadmap will be guided by an upcoming conference on transitioning away from fossil fuels hosted by Colombia and the Netherlands in April.

Corrêa do Lago went on to rapidly gavel more of COP30’s key texts, including on the “global goal on adaptation” (GGA), and the just transition and mitigation work programmes.

However, Panama, supported by other Latin American countries and the EU, took to the floor in plenary to say its attempt to raise an intervention ahead of the GGA being gavelled was ignored by the Brazilian presidency.

Colombia also took the floor, to say that its attempt to raise a flag before the adoption of the mitigation work programme was also ignored.

The closing plenary was suspended for an hour to allow for further consultations between the presidency and parties unhappy with the adoption process.

After the plenary resumed, delegates spent another six hours gavelling through more texts, including on gender equality and a host of more technical items, in addition to hearing more statements from countries and observers.

According to Carbon Brief calculations, in total, there were more than 150 pages of decision text adopted across the various bodies meeting at the COP.

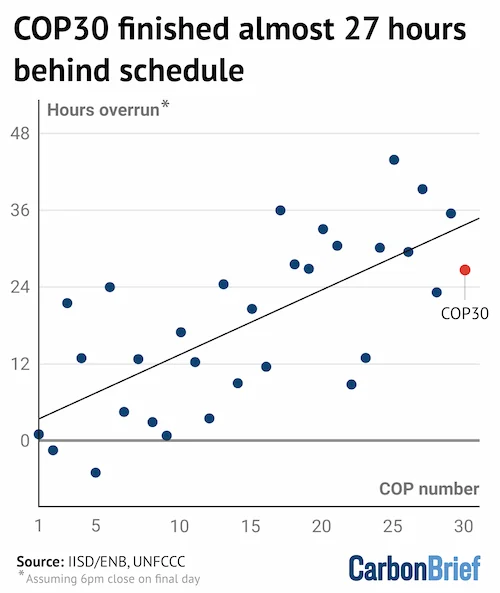

COP30 officially finished at 8:44pm on Saturday evening, making it only the 11th longest climate talks in history.

Adaptation

One of the biggest negotiated outcomes at COP30 concerned efforts to adapt to the impacts of climate change, with Corrêa do Lago dubbing it the “COP of adaptation”.

In particular, negotiators were expected to agree to a list of “indicators” that would allow countries to measure their progress under the global goal on adaptation (GGA). A much-reduced set of indicators was, ultimately, agreed at COP30.

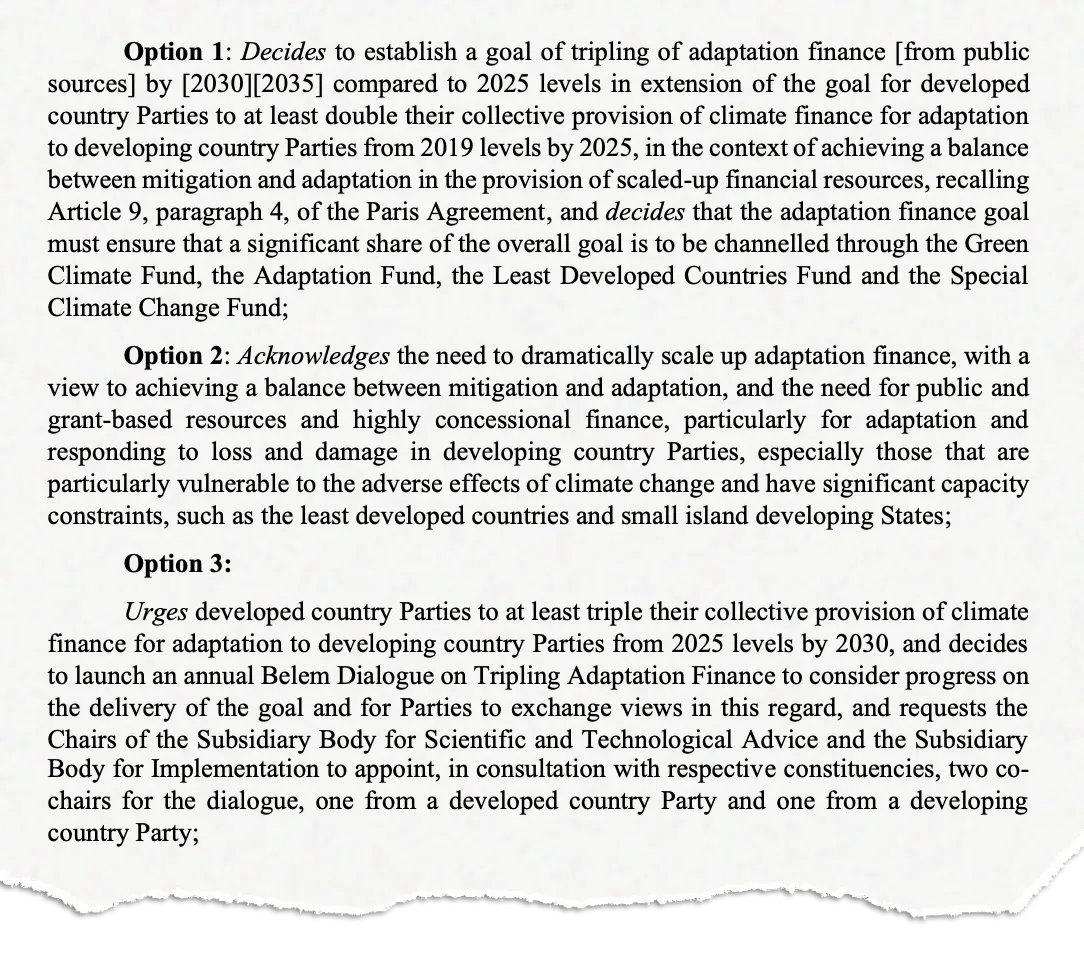

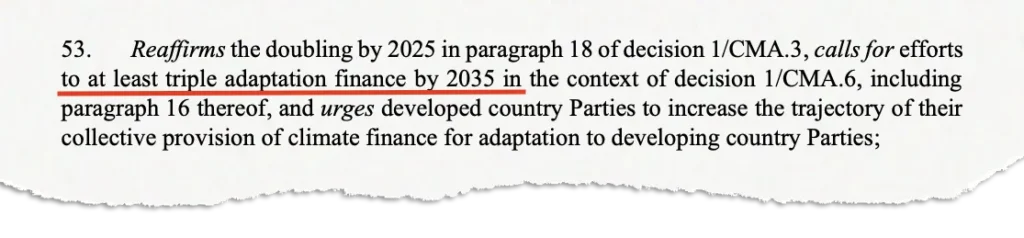

However, calls for a new adaptation finance target quickly drew focus. The key “global mutirão” decision at the talks “calls on” countries to triple adaptation finance by 2035.

This followed a request from the LDCs at climate talks in Bonn earlier this year for a target to triple adaptation finance by 2030.

In 2021, a target to double adaptation finance to $40bn by 2025 was agreed at COP26 in Glasgow, UK.

However, a recent report from the UN Environment Programme (UNEP) found that, in 2023, developed nations provided just $26bn in adaptation finance to developing nations.

This marks a drop from $28bn in 2022 and is far short of the annual adaptation-finance needs for these nations, which UNEP puts at around $310bn annually out to 2035.

UNEP warned that, based on current trends, developed nations will miss the Glasgow goal.

A negotiation on a new adaptation-finance target for the years after 2025 was not included in the COP30 agenda. Over the course of the first week, a new goal was proposed in discussions on the GGA, national adaptation plans (NAPs) and the adaptation fund.

The LDCs’ proposal to triple finance to $120bn by 2030 was supported by small-island states (AOSIS), the African group, Grupo Sur and others.

It faced opposition, primarily from developed countries in the EU and the Environmental Integrity Group (EIG), the latter of whom noted that reference to such a target would be construed as an attempt to renegotiate the “new collective quantified goal” (NCQG).

Speaking during a press huddle, Aichetou Seck, an LDC adaptation negotiator from Senegal, said:

“We cannot keep returning to debate figures; the figures will only grow if action does not follow. What is needed now is a COP that elevates adaptation and sends a clear signal that adaptation finance is indispensable.”

With no official home, the question of a new adaptation-finance target was taken up within the presidency consultations. (See: Global mutirão.)

The first mutirão draft included a number of options, including one to “establish a goal” of developed countries tripling their provision of adaptation finance, with options for this to come exclusively “from public sources” and proposed deadlines of either 2030 or 2035.

There were also less ambitious proposals, merely “urging” a tripling of adaptation finance or “acknowledging” the need for a general increase in this finance.

Simultaneously, negotiations got underway on the GGA. Over the past two years, experts worked to turn a list of 10,000 potential indicators for tracking adaptation into just 100.

Cracks quickly emerged at COP30. Unity within the G77 and China coalition of developing countries fractured on the first day of negotiations, when the African group proposed a two-year “political refinement” process ahead of indicator adoption. Latin American countries called for adoption at COP30.

The African group argued that the indicators were “intrusive” and that African countries required more adaptation finance to take them on.

Richard Muyungi, African group chair, told Carbon Brief in the first week:

“We need to put guardrails or caveats on the adoption [of the indicators]. For example…the indicators should not infringe on the sovereignty of countries, asking countries to change their laws, their strategies. I mean, you cannot ask my country to change laws, because they want to address the global goal.”

Speaking during a press conference, Jacobo Ocharan, head of political strategies at Climate Action Network (CAN) International, noted that 48 of the indicators required support and finance in order to be actionable.

He asked: “What are you going to measure…in two years if that finance is not there?”

Other areas of disagreement within the GGA included opposing views on topics such as the Baku adaptation roadmap, the concept of “transformational adaptation” and language on “cross-cutting considerations”.

However, the key sticking point remained the indicators. Jeffrey Qi, policy advisor with IISD’s resilience program, told Carbon Brief that negotiators were trying to find a “tricky” balance. He said this included keeping indicators around domestic resource mobilisation that developed countries wanted, but which developing nations opposed.

The issue was complicated by the continued divide within the developing-country groups.

Speaking in a media huddle, Latin American ministers highlighted adaptation finance, but continued to emphasise the need to adopt the indicators. Edgardo Ortuño Silva, environment minister of Uruguay, said:

“We will not accept less in our conference than the adoption of action indicators and implementation means consistent with the [UNFCCC] and the Paris Agreement.”

Draft negotiation texts showed little progress in the second week, with the number of undecided, bracketed parts of the text doubling to nearly 100.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Bethan Laughlin, senior policy specialist at the Zoological Society of London, said that the “massive elephant in the room is the lack of adaptation finance”, but that a goal within the presidency text could “unlock a huge amount of it”.

As negotiations drew to a close a new text seemingly found a landing ground. It included an annex of 59 of the potential 100 indicators, emphasising that they “do not create new financial obligations or commitments”.

The text also contained plans for a two-year “Belém-Addis vision” to further refine the indicators.

The only remaining bracket within the text was a placeholder for the final adaptation finance target from the mutirão.

This text was released on the same day and included weakened language that merely “call[ed] for efforts” to triple adaptation finance compared to 2025 levels by 2030.

Ana Mulio Alvarez, researcher on adaptation at thinktank E3G, told Carbon Brief that the indicator compromise was “satisfactory”, as it allowed the framework to advance while including further refinement, but that some aspects remained “ambiguous”.

She added that a small group of negotiators had altered some of the indicators, “render[ing] some unusable, suggesting the list may need to be revised again”.

The final GGA text retained the adoption of the 59 indicators and the two-year programme “aimed at developing guidance for operationalising the Belém adaptation indicators”.

The GGA was gavelled through during the closing plenary, but met with a mixed response. While there was clapping in the room, Latin American countries, the EU, Canada and others voiced criticism and said they could not support the outcome.

Panama, for example, referred to it as a “rushed draft” and argued that this “is not how we reach a global goal on adaptation”. The statement was met with a round of applause.

Following a pause in the plenary, Corrêa do Lago requested further work on the GGA at the Bonn climate talks in June 2026.

The GGA text retained the placeholder for an adaptation-finance goal within the final mutirão text.

Ultimately, this “reaffirm[ed]” the doubling goal from Glasgow, “call[ed] for efforts” to triple adaptation finance and “urge[ed]” developed countries to increase the “trajectory” of their finance provisions, largely mirroring the previous draft.

However, the deadline for the tripling target was pushed back by five years and the reference to 2025 as the baseline for this goal was removed.

Joe Thwaites, a senior advocate for international climate finance at NRDC, told Carbon Brief there was “ambiguity” in the goal, but added:

“The decision to triple was taken in 2025 and the old goal expires in 2025, so absent anything saying otherwise, that should be the assumption.”

Carbon Brief understands that, with no baseline officially in the text, the Standing Committee on Finance could provide a space where the baseline is defined by parties.

Beyond the GGA and adaptation finance, negotiations on NAPs followed on from tense sessions at COP29 and in Bonn, both of which ended without agreement.

According to Qi, within the NAP negotiations, “finance is the main issue…if you look at the text, it’s the same issue over and over again. So you just need to streamline everything.”

Ultimately, a decision was adopted in COP30’s closing plenary, marking an end to the stalemate in NAP negotiations.

Additionally, negotiations took place under the Adaptation Fund, with countries announcing financial pledges towards its annual target of $300m. The final text “notes with concern” that the target could not be met and “underscores the urgency of scaling up financial resources”.

Ambition and 1.5C

The key “global mutirão” decision at COP30 aims to keep the limit of 1.5C “within reach”, but says that the “carbon budget” for this is “now small and being rapidly depleted”.

For the first time in a COP text, it also acknowledges that there is likely to be an “overshoot” of 1.5C, saying that both the extent and duration of this needs to be “limit[ed]”.

It responds to this by launching two ill-defined voluntary initiatives, led by the COP presidencies: a “global implementation accelerator” (GIA) and a “Belém mission to 1.5C”.

It also “calls on” countries to “accelerat[e] the full implementation” of their climate pledges and to “striv[e] to do better”, as well as “inviting” them to draw up “implementation and investment plans”, to align their climate strategies with plans for economic development.

These measures fall well short of the outcomes that had been demanded by a broad coalition, including the EU and small-island states (AOSIS).

The decision does not mention fossil fuels, the largest source of planet-warming emissions, or a mooted “roadmap” to transition away from their use. (See: Fossil-fuel roadmap.)

In the closing plenary, the EU called the decision a “missed opportunity”. During heated negotiations on the penultimate day, it had called for a “concrete, annual process to…keeping 1.5C alive not in speeches, but in practice”. The outcome does not deliver this.

Fernanda Carvalho, head of policy for climate and energy at WWF, told Carbon Brief that the outcome reflected the “lowest common denominator, therefore [it] is weak”.

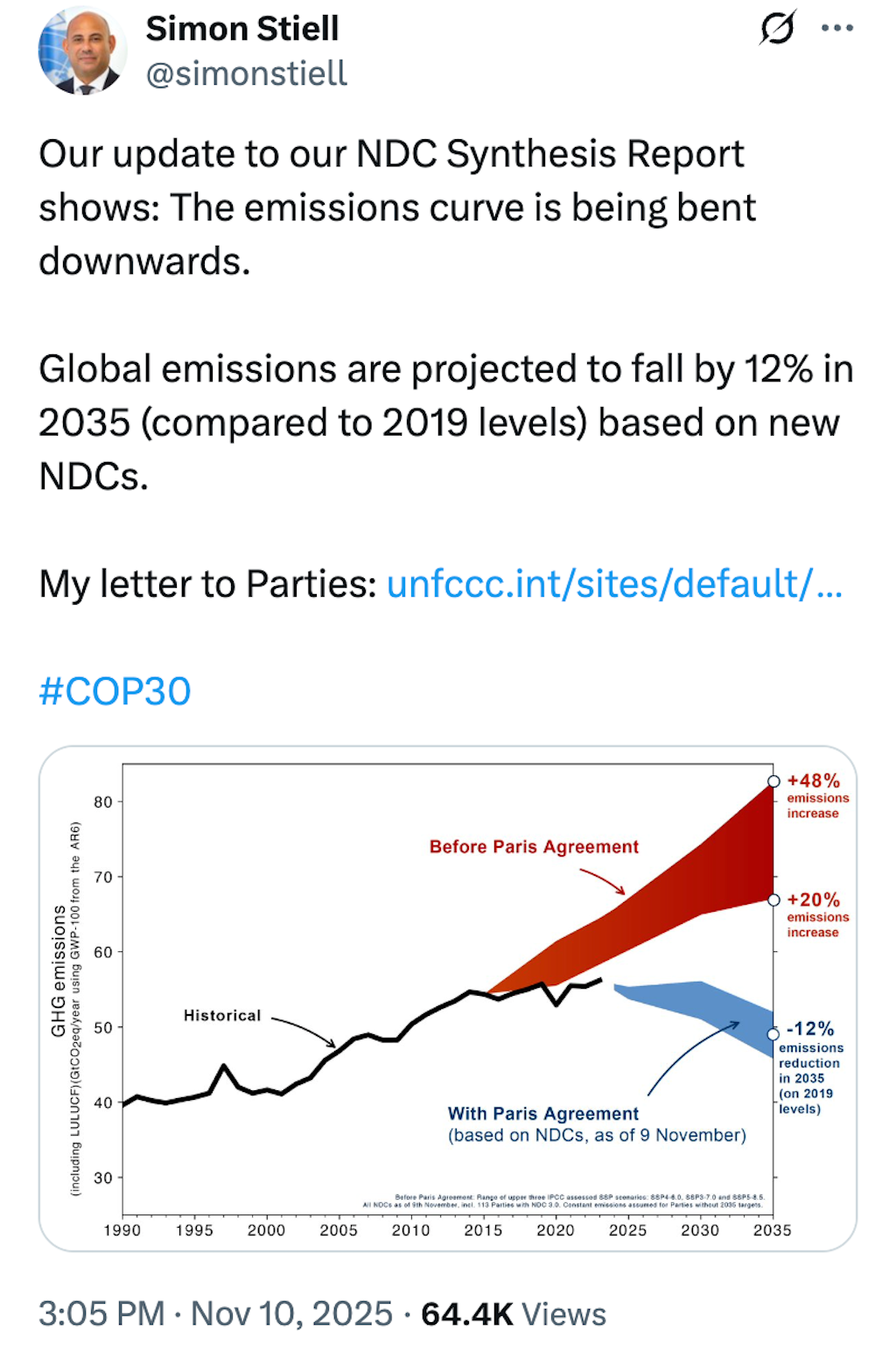

Countries had arrived in Brazil as a series of reports made clear that they remained badly off track for limiting warming to 1.5C, even though the outlook has improved since 2015.

Despite countries submitting more than 100 new climate plans, known as “nationally determined contributions” (NDCs), the world remains on track for 2.3-2.5C of warming by 2100.

Ahead of the summit, this had prompted AOSIS to propose a “dedicated space” on the COP agenda in which to “assess collective progress…and drive ambition toward 1.5C”.

This idea was not added to the official agenda. Instead, it was taken up in “presidency consultations” along with three other contentious topics, which went on to be combined into a single COP30 decision known as the “global mutirão”. (See: Global mutirão.)

After a week of closed-door discussions, the presidency published a draft of this outcome that included options related to the call from AOSIS and others. In paragraph 44, one option would have created annual NDC discussions linked to a “transition away from fossil fuels”.

Although this option reflected some of the priorities put forward by AOSIS, it did not include a clear process through which to take the “annual consideration of NDCs” forwards.

Separately, this draft also included an option making a direct link back to paragraphs 28 and 33 of the global stocktake, which called for fossil-fuel transition and ending deforestation.

However, this direct link back to the stocktake and the idea of annual discussions on NDCs were both opposed by the like-minded developing countries (LMDCs, including China, India and Saudi Arabia) and the African group, according to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin.

The second draft of the mutirão text, published on 21 November, made no mention of fossil fuels, roadmaps, paragraph 28 of the global stocktake or annual discussions on NDCs.

The final draft – published on 22 November after all-night negotiations – is broadly similar, but fleshes out the GIA, among other changes.

It adds “information sessions” to be held under the GIA in Bonn in June 2026 and at COP31 – where the COP30 and COP31 presidencies will report back – as well as a related “high-level event”.

It also ties the GIA to the “UAE consensus” – the overarching outcome of COP28, where the global stocktake and its paragraph 28 on energy transition was adopted.

This “implicitly keeps the transition away from fossil fuels alive”, said Cosima Cassel, climate diplomacy lead at E3G. The Belém mission to 1.5C also “has potential” to be linked to roadmaps on fossil fuels and deforestation launched by Brazil. She told Carbon Brief:

“Given the resistance from major [fossil-fuel] producers, even maintaining that implicit link was hard-won…What we have is essentially the most that could be agreed without triggering a veto. The ambition is lower than many wanted, but the political hooks do exist. Much will depend on how Brazil, Australia and Turkey choose to drive this agenda forward.”

(Notably, the G20 declaration, published after the COP30 deal had been wrapped up, includes text that explicitly “welcomes” the outcome of the stocktake, even as similar language had proved elusive in Belém.)

Catherine Abreu, director of the International Climate Politics Hub, told Carbon Brief that, in order for the UN climate talks to “get real”, they would need to address the key issues raised by different groups of countries, including finance, trade and the “social dimensions of transition”, as well as a “laser focus” on the biggest emissions sources, fossil fuels and deforestation. She said:

“Yet the final decisions made on these issues rely on dialogues and coalitions that aren’t binding and have few accountability anchors within the UN climate process. It will take diligent attention from countries and COP presidencies – and civil society – to ensure the processes launched in Belém actually work to drive implementation.”

There were also related discussions in Belém on taking forward the outcomes of the first global stocktake under the “UAE dialogue”. Efforts to agree what this dialogue should talk about had failed at COP29 in Baku.

At COP30, countries initially remained deeply divided, between groups that only wanted it to discuss climate finance and those that wanted to talk about all of the stocktake outcomes.

After a “bridging proposal” offering compromise language was put forward by Latin American countries (AILAC), negotiations closed in on a broad scope for the UAE dialogue, covering all outcomes of the stocktake, but with a particular focus on finance.

The final decision on the dialogue says it will be held at the Bonn meetings in 2026 and 2027, with countries and observers invited to submit their views three months in advance.

Reports of these sessions will feed into the second stocktake in 2028 and the UAE dialogue itself will conclude with a ministerial “roundtable” at COP32 in 2027.

The decision also “encourages” the scientific community, including the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), to “consider how best to provide inputs for the global stocktake in a timely manner”.

Manjeet Dhakal, adviser to the least-developed countries (LDCs) told Carbon Brief that “significant compromises” had been made in order to “keep the process moving”. He said:

“There is now a clear need for strong implementation and tracking of the first GST [global stocktake] outcome through the UAE dialogue next year. Looking ahead, the IPCC AR7 working group reports should serve as critical inputs for the second GST. The global stocktake must help drive ambition to keep 1.5C within reach and close the implementation gap.”

Climate finance

Finance to help developing countries deal with climate change was not top of the agenda at COP30, but still influenced much of the event.

An effort by India, Arab states and other developing countries to elevate the issue ended up forming part of the Belém summit’s core “mutirão” package. (See: Global mutirão.)

The package launched a new “work programme” for countries to discuss concerns about climate finance, as well as a new goal to triple adaptation finance. (See: Adaptation.)

Most finance-related issues at COP30 could be traced back to a new target agreed last year, which included a $300bn-a-year goal, as well as a vaguer effort to reach $1.3tn, both by 2035.

This “new collective quantified goal” (NCQG) faced a backlash from many developing countries at the time, who argued it was insufficient.

The parties responsible for providing finance – including the EU, the UK and Japan – have been unwilling to consider more ambitious targets, often citing domestic fiscal pressures.

These divergences spilled over into COP30. As negotiators debated fossil-fuel phaseout, just transition and adaptation, developing countries argued that they needed more finance for all these activities.

In particular, there was a focus on Article 9.1 of the Paris Agreement, which says developed countries “shall provide” climate finance. In practice, this means public money.

In contrast, the $300bn target covers both funds “provided” and climate finance from a “wide variety of sources”, such as “mobilised” private spending.

Some developing countries argue that this formulation will enable developed countries, many of which have cut their aid budgets, to meet the goal without raising their contributions much.

Ahead of COP30, the LMDCs and Arab group – together representing around 40 countries, including India, China and Saudi Arabia – called for a three-year “work programme” on implementing Article 9.1. They also had support from the African group.

Chandni Raina, the Indian climate-finance negotiator who caused a stir last year when she publicly rejected the NCQG, told Carbon Brief:

“[Article] 9.1 is the catalyst that can enable us to mobilise finance of the kind that we need for climate action…We understood that the developed countries didn’t want to discuss 9.1 at all, because that puts the onus on them.”

EU lead negotiator Jacob Werksman said the bloc’s view was that the whole of Article 9 – covering “a wide variety of sources” – was important. He told a press conference: “We are prepared to talk about 9.1, but in the context of Article 9 as a whole.”

Developed-country representatives also stressed the importance of expanding the donor base to include wealthy, developing countries and changing global financial architecture to boost finance.

The LMDC-Arab grouping’s push for an Article 9.1 work programme formed part of the wider presidency discussions that dominated so much of COP30. (See: Global mutirão.)

Not all developing countries appeared to feel as strongly about the issue of Article 9.1, specifically. Ziaul Haque, additional director general at the Bangladesh Ministry of Environment, told Carbon Brief:

“We need to have good discussions around 9.1, but whether there is dedicated space or not…We are flexible.”

In the end, the mutirão text contains the compromise of a two-year programme covering all of Article 9 and a footnote stating the decision does not “prejudge” NCQG implementation.

Avantika Goswami, a climate policy lead at the Centre for Science and Environment, told Carbon Brief that, despite being “suboptimal”, the programme would provide “a concrete space to raise various issues on climate finance in the coming years, including on public finance flows”.

Another finance element that made it into the mutirão package was the “Baku to Belém roadmap”. Launched as part of the NCQG, this presidency-led initiative was meant to lay out how the $1.3tn part of the goal could be met.

Independent analysis commissioned for the roadmap suggests the vast majority will likely come from private-sector investment.

The roadmap was launched just before COP30. During the first week of the summit there was a “high-level” event in which the Brazilian and Azerbaijani presidencies laid out the next steps.

Major donors voiced their support for the Baku to Belém roadmap at the event, while both Kenya and AILAC indicated that they wanted it reflected in COP30 negotiated outcomes. However, the roadmap was a lower priority than other finance issues for many developing countries.

“We are more interested in the $300bn goal, that is where the provision and mobilisation will primarily take place,” Raju Pandit Chhetri, an LDC advisor, told Carbon Brief.

In the end, the mutirão package only “takes note” of the roadmap. However, the text also “decides” – a relatively strong active verb from a legal perspective – to “urgently advance actions” to scale up finance to $1.3tn.

There were a number of other negotiating tracks that involved climate finance at COP30.

One track focused on Article 2.1c of the Paris Agreement, which concerns “making finance flows consistent” with climate goals.

The breadth of this topic is potentially huge, so countries have been engaged in a “dialogue” to arrive at a more shared understanding.

Ultimately, parties at COP30 decided to keep discussing the issue under a new “Veredas dialogue” until 2028, despite the Arab group initially wanting to end discussions.

Finally, another track saw negotiators discuss “biennial communications”, in which developed countries lay out plans for future climate-finance provision.

Parties had a chance at COP30 to update the information they should provide, to help developing countries plan for the future, but ultimately the changes were modest.

With little space for finance in formal negotiations, this workstream became an opportunity for developing countries to make ambitious demands, which did not make it into the final text. These included calling for the NCQG goal to exceed $300bn and for the developed nations to “reform [their] budgetary processes”.

‘Unilateral trade measures’

After several failed attempts to bring climate-related “unilateral trade measures” (UTMs) onto the agenda at previous COPs, the issue was taken up in Belém as part of presidency-led discussions and reflected in the key outcome of the summit, the “global mutirão”.

This decision creates three annual “dialogues” on trade, to be held at the Bonn meetings in 2026, 2027 and 2028. It also “reaffirms” that climate measures, “including unilateral ones, should not constitute” trade restrictions that are “arbitrary” or “discriminat[ory”.

This is the first-ever mention of trade measures in a COP cover decision.

In Belém, the issue of such trade measures had once again been raised by Bolivia on behalf of the like-minded developing countries (LMDCs, including China, India and others).

Within the presidency-led consultations, the LMDCs called for a recurring agenda item on trade, Tuvalu supported a dialogue and the African group proposed a system for countries to report trade measures to the UNFCCC.

Russia, meanwhile, warned that “killing off” UTMs again “will poison other issues and result in distrust”, reported the Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

On Sunday, the presidency published a summary of its consultations, containing five options for a decision on trade measures, including dialogues, roundtables or the creation of a platform.

In a first draft of the mutirão text, published on 18 November, the options had been refined to four.

David Waskow, director of the World Resources Institute’s international climate initiative, told a media briefing that trade is a “real issue” for some countries and not just a “bargaining tactic or some sort of chit that’s being put on the table”.

He added that the EU “feels strongly” about the ways trade measures support climate action, but also developing countries have “real concerns” about how those measures play out.

On what was scheduled to be the last day of COP30, the presidency published a second draft of the mutirão text “request[ing]” the subsidiary bodies to hold an annual dialogue in Bonn from 2026-2028 on trade and international cooperation.

Avantika Goswami, climate policy lead at Delhi-based thinktank the the Centre for Science and Environment, told Carbon Brief that, while “it is not ideal to not have a formal agenda item” on UTMs, the reference to the UN climate convention in the text “is welcomed”, as well as the dialogues that will take place over the next three years. Goswami added:

“At the very least, this will elevate the issue of unilateral trade measures to be more high-profile within the COP space and will provide a forum for countries to discuss their concerns and challenges, as well as possible solutions for the way forward.”

Alongside the discussions under the presidency, UTMs continued to crop up within different negotiation streams, including on just transition, “response measures” and technology.

In Baku in 2024, a four-year work plan to discuss response measures included an item on the “cross-border impacts” of “measures taken to combat” climate change. This established a formal space for trade-related climate measures and their impacts to be discussed and assessed, for the first time in climate talks.

Early options in draft texts for the response measures workstream at COP30 referred to presidency consultations on UTMs and to “cross-border impacts” of climate measures.

Subsequent drafts dropped the reference to UTMs, but retained language on cross-border impacts.

By the penultimate day of the talks, the presidency proposed a decision text for the response measures forum. This included a two-day global dialogue on response measures each year from 2026-29. After relatively few changes, this decision was adopted.

UTMs were also discussed in relation to just transition work programme (JTWP), following on from a LMDC proposal in Bonn to have them added to the agenda. The compromise in June was that trade measures were added to the work programme.

In Belém, Saudi Arabia said that unilateral trade measures would “hinder [climate] ambition, violate the right to development and exacerbate poverty, clearly attacking the very concept of just transitions”, according to Third World Network (TWN).

Meanwhile, China called UTMs “the new injustice”, whereas Japan did not support UTMs being discussed in the JTWP, TWN reported.

There was a particular focus on the EU’s “carbon border adjustment mechanism” (CBAM), with a draft text published in the second week, “not[ing] with concern” its potential impact.

Speaking during an EU press conference, European commissioner Wopke Hoekstra said the bloc is “more than happy to discuss” CBAM, but pushed back on criticism. He added that CBAM was not a unilateral trade measure, but “part of our climate toolbox”.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Meena Raman, head of the climate change programme at Third World Network, said:

“This is the issue about equity, linking it to the trade measure. So it’s not about saying that what the EU is doing is not important for its own industry, but it’s being viewed as a protectionist, discriminatory measure rather than cooperating. It feels punishing.”

However, the final decision on the JTWP removed all references to trade. Similarly, all references to “trade barriers” were removed in the final decision on the “technology implementation programme”.

Climate science

Bangladesh, the EU and the UK were among those left “disappointed” by COP30 conclusions on climate science, reached at the end of the first week of the summit.

The text on “research and systematic observation” (RSO) failed to endorse the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) as the “best available science”.

It noted the need for “the integrity of climate change information”, but – unlike an earlier draft – it made no mention of the need to “counter misinformation on climate change”.

The text also failed to mention the latest findings on the state of the climate, as presented to the summit by the IPCC, the World Meteorological Organization (WMO) and others.

Speaking in the closing plenary of the first week of COP30, Bangladesh said it was “deeply concerned” about efforts to avoid endorsing the IPCC. It said:

“We are also deeply concerned about the consistent attempt to weaken the reference of the IPCC as the provider of the best available science, not only under this agenda item, but across several others. The IPCC remains the cornerstone of credible policy-relevant climate knowledge and its integrity must be protected.”

Similar interventions came from Australia, Canada and New Zealand. In contrast, Saudi Arabia, speaking for the Arab group, as well as Iran, called for finance to support further climate research.

(The headline “global mutirão” decision, adopted a week later, “recognises the centrality of equity and the best available science…as provided by the IPCC”.)

The UK said it was “deeply concerned that…it was not possible to capture vital scientific observations of the state of the climate in our conclusions”.

(An earlier draft had noted that 2025 was on track to be among the three hottest years on record, “primarily [as a] result of greenhouse gas emissions”. It had also flagged “record increases” in CO2 concentrations and “irreversible changes” in the Earth’s icy regions.)

The EU contrasted this inability to acknowledge the state of the world’s climate with Brazilian president Lula’s description of the summit as the “COP of truth”.

According to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin, the Arab group and India opposed references to the IPCC and to specific findings from the WMO. It also reported that Saudi Arabia had “called for deleting a reference to enhancing efforts to ‘counter misinformation’.”

Several sources who were not authorised to speak with the media tell Carbon Brief that COP discussions on climate science have been “getting harder” and “more political”. One says that a “very small group of countries” is behind this resistance.

However, a summary of the first week at the COP from the research consortium CGIAR stresses the need to understand the motivations behind these tensions. It says:

“[T]o truly understand these tensions, we must go beyond labels like ‘anti-science’ or ‘denial’. As some observers noted, resistance to scientific references often stems from legitimate concerns about fairness, representation and historical imbalance in how science – especially the IPCC – is shaped.”

Still, a number of scientists expressed their “concern” over the COP30 outcome. Prof Pamela McElwee at Rutgers University said the situation “mirrors” recent discussions under the Convention on Biological Diversity, calling this a “concerning moment”.

Prof Piers Forster, director of the Priestley Centre, said it had been an “honour” to present the Indicators of Global Climate Change study to the COP.

He added that it had been “gutting to see paragraphs describing our work and that of WMO and IPCC colleagues removed and eroded”.

Similarly, Prof Joeri Rogelj, director of research at the Grantham Research Institute, responded to the situation by saying that it was “very disappointing”.

COP30 was also unable to agree on asking the IPCC to align its seventh assessment cycle (AR7) with the second “global stocktake” under the Paris Agreement, due in 2028.

This is a reprisal of ongoing disputes, which have also been taking place at the IPCC.

Instead, a separate decision “encourages” the scientific community to “provide the best available scientific inputs” and “invites” organisations including the IPCC to “consider how best to provide inputs for the [next] global stocktake in a timely manner”.

Finally, the RSO text does “note…with concern” the funding issues reported by the Global Climate Observing System (GCOS), described by Agence France-Presse as a “crucial UN-backed programme that tracks and evaluates data on the atmosphere, land and ocean”.

In an interview with the newswire, GCOS deputy chair Peter Thorne said budget cuts from the US left the system “under considerable strain”, adding:

“This is possibly the first time we’re looking at an acute reversal in our capability to monitor the Earth, just when we need it the most.…GCOS itself will close its doors at the end of 2027 without additional funds.”

Just transition work programme

The outcome of the “just transition work programme” (JTWP) at COP30 has been hailed by many in civil society as a “victory”, thanks to the adoption of a new institutional mechanism.

Ahead of the summit, a number of civil society groups put together a proposal for a mechanism they dubbed the “Belém action mechanism” (BAM). This would provide a centralised hub to support just transitions around the world.

Over the course of the two weeks, organisations published an open letter calling for the creation of the mechanism, numerous “actions” took place within the corridors of COP, banners bearing the “BAM!” logo were carried during the people’s protest and badges were worn by delegates.

On the second day of negotiations, the G77 plus China put forward a proposal for a just transition “mechanism”, which would provide technical assistance, international cooperation and help foster partnerships in an effort to address implementation gaps.

This proposal “fires the starting gun on serious negotiations,” Teresa Anderson, global lead on climate justice for ActionAid International, said in a statement.

Norway, the UK and others, however, opposed the creation of a mechanism, arguing it would duplicate existing systems, take at least five years to set up and citing a lack of funding, according to the Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB).

Speaking to Carbon Brief, Dr Leon Sealey-Huggins, a senior campaigner at the charity War on Want, said a mechanism would help resolve areas of duplication that already exist in the just transition space, by providing a centralised home for resources.

At the end of the first week, the EU proposed a just-transition “action plan” as an alternative to a mechanism, according to the ENB. It suggested this would be hosted by the UNFCCC and facilitate knowledge exchange, enhance capacity and ensure participation of non-party stakeholders.

JTWP co-chair Joseph Teo noted that there was overlap between the proposals for an action plan or a mechanism. However, Dr Amiera Sawas, head of research and policy at the Fossil Fuel Non Proliferation Treaty Initiative, told Carbon Brief that an action plan was a “less ambitious proposal” that was “more about mapping and understanding what potential initiative exists”.

In the second week of COP30, negotiators tried to find agreement on either a mechanism or an action plan.

A text published on 17 November listed both as options. Additionally, it included language on the “meaningful participation” of a range of groups, including, for the first time, people of African descent. This language made it into the final text.

Anabella Rosemberg, senior advisor on just transition at NGO umbrella group CAN International, told Carbon Brief that developed countries disliked the word “mechanism” more than the functions proposed within the text. But she said that the alternative proposal for an action plan had flaws, adding:

“It doesn’t give the sense [that] this is the single address where I can send my request and I will get an answer on where I can be supported. It sounds very silly, but there is a difference if you have a coordinating entity or you don’t. Because if you don’t, it’s just a dialogue. It’s a series of events.”

By the end of the summit, negotiations were able to converge on the idea of establishing a just transition “mechanism”, as set out in the final text.

Dr Sealey-Huggins welcomed the outcome, despite wider aspects of COP30 “falling short”. He added:

“This mechanism is not the end of the struggle, but it is a vital victory that anchors our fights for justice within the UN… BAM shows the power of grassroots and frontline leadership.”

However, other elements of the text were ultimately “watered down”, according to Antonio Hill, advisor at the Natural Resource Governance Institute (NRGI).

Other points of contention within the just-transition negotiations included the cross-border impact of climate-related trade measures (see: Unilateral trade measures) and suggestions for the inclusion of a footnote on gender (see: Gender).

There was also disagreement on some language in the texts, including on connecting a 1.5C warming limit with a just transition and mentions of a transition away from fossil fuels. There was also disagreement on the role of “transition fuels” and text about integrating the outcomes of the first “global stocktake” into the work programme.

Additionally, earlier drafts of texts included a paragraph that “recognise[d]” the “risks arising from the extraction and processing of critical minerals”.

This was the first time that minerals have been included in a text within the UNFCCC process. However, there were diverging views on the inclusion, Hill told Carbon Brief: