Marking the 10th anniversary of the Paris Agreement, COP30 is seen as a crucial test of the world’s resolve to tackle climate change. At a time of faltering multilateralism, worsening climate-related destruction and a lack of ambition in national pledges to cut greenhouse gas emissions, the stakes for the UN climate summit in Belèm are higher than ever.

We take a look at the big questions facing this Amazon COP – from efforts to raise weak national climate targets and transition away from fossil fuels, to long-overdue action on adaptation and forest finance.

How will COP30 address the global ambition shortfall?

In the year leading up to COP30, the global climate community watched closely for countries’ new national targets, a key gauge of the world’s commitment to cutting greenhouse gas emissions. As the nationally determined contributions (NDCs) belatedly trickled in, a clear picture emerged: the plans fall far short of what is needed to avoid the worst climate impacts.

If those commitments are turned into action, global emissions are still only expected to fall about 10% below 2019 levels by 2035, a preliminary UN climate assessment found – far short of the roughly 60% cut IPCC scientists say is needed to limit global warming to 1.5C.

“Current commitments still point to climate breakdown,” said UN Secretary-General António Guterres, indicating that a temporary overshoot of the more ambitious Paris temperature goal is now “inevitable”.

Heading into COP30, he called on world leaders to deliver “a bold and credible response plan” to close the gap. This leaves the Brazilian COP30 presidency with the unenviable task of trying to push countries to ramp up their ambition and go beyond the NDCs that they have just submitted.

How – or even whether – that will happen is still unclear.

A round of informal consultations in September brought a clash of views into public view. Large emerging economies, including China, Saudi Arabia and India, pushed back on the need to discuss climate plans – arguing the topic is not on the summit’s agenda and will be taken up in the next Global Stocktake. But rich nations, least-developed countries (LDCs), small island states and Latin American nations want a COP30 decision that lays out a pathway for accelerating climate action in the years ahead.

If countries were to ultimately agree on a collective response, a negotiated cover decision could be a natural home for it. Brazil professed its strong opposition to that option for months, but it recently warmed up to the idea of producing an “omnibus” decision that could incorporate all the main outcomes of the summit, including those not covered by the formal agenda.

But some seasoned COP participants want Brazil to take a radically different approach. That could mean, for example, producing an “Implementation Plan“, that, instead of listing vague promises, provides detailed guidance on the way forward while trying to connect the negotiations to the real world.

What’s next for the fossil fuel transition?

At COP28 in Dubai, countries reached a landmark agreement to transition away from fossil fuels in their energy systems in a historic first for a UN climate summit. Yet, nearly two years later, those words have not been matched by meaningful action.

According to the latest Production Gap Report, governments are collectively planning even higher levels of fossil fuel production than they were at the time of the Dubai deal. By 2030, planned production is projected to exceed levels consistent with limiting global warming to 1.5C by more than 120%.

And in their latest national climate plans submitted this year, only about a third of countries express some form of support for the transition away from fossil fuels, an analysis by Carbon Brief found.

Leo Roberts, a programme lead on energy transitions at think-tank E3G, said there needs to be a high-level visible signal emerging from this COP, but that is unlikely to come from the formal negotiations. Oil-producing nations have blocked any progress on the fossil fuel transition at COP29 last year and at last June’s mid-year session in Bonn.

“What we need to see is some process that can act as a bridge between the real world and negotiations,” added Roberts, “a dialogue space that can ultimately produce some form of roadmap on the transition away from fossil fuels”.

This idea should count on political backing from Brazil, despite the country’s plans to expand oil and gas production. The need for a roadmap was first floated in the country’s NDC last year and Environment Minister Marina Silvia has been publicly championing it in the run-up to COP30.

Last week, she called on world leaders to send a clear message on the need for a “just, planned, gradual and long-term decommissioning of fossil fuels” as they take to the stage in Belém this week.

Several other nations should be getting behind this push. Ministers from 23 countries, including the UK, Germany, France and small-island nations, said “international cooperation and global tracking” are needed to make sure the transition happens fast enough in a joint statement published on the sidelines of the UN General Assembly.

The European Union wants the COP30 outcome to ask all nations, and particularly major emitters, “to operationalise their contribution” to the global call to transition away from fossil fuels. Colombia is set to host the first international conference on phasing out fossil fuels in April 2026, aiming to give countries a global platform for co-operating on the transition away from coal, oil and fossil gas.

Big banks’ lending to coal backers undermines Indonesia’s green plans

In the formal negotiations, Brazil has made advancing the just transition work programme one of its top priorities, after countries failed at COP29 to agree on a deal to support workers and communities affected by the shift to cleaner energy.

Civil society groups are pushing the idea of a new “Belém Action Mechanism” under the programme, an initiative aimed at unifying and strengthening global efforts to ensure that the shift away from fossil fuels is fair, inclusive, and equitable. The idea is to identify barriers, opportunities and international support by providing countries with global coordination.

Will adaptation take centre stage?

As the world fails to limit global warming to agreed levels, climate impacts are expected to grow even more intense and frequent. This grim outlook translates into an increasingly urgent need to strengthen countries’ ability to withstand worsening floods, deadlier heatwaves and more prolonged droughts.

But adaptation – often described as the “Cinderella” of climate action – remains largely overlooked and severely underfunded. Brazil has pledged to change that, putting adaptation at the centre of this year’s UN climate summit.

“Climate adaptation is no longer a choice that follows mitigation – it is the first half of our survival,” COP30 president André Aranha Corrêa do Lago said in a recent letter calling for “urgent and tangible” outcomes in Belém.

In the formal negotiations, the big-ticket item will be the Global Goal on Adaptation (GGA). Governments should agree on a set of indicators that can be used to measure progress towards the GGA’s broad targets on areas including sanitation, food, health and infrastructure.

Technical experts have whittled down thousands of proposed indicators to a more manageable list of 100, which will serve as the basis of discussions in Belèm.

Natalie Unterstell, president of Brazil’s Instituto Talanoa, told a Climate Home briefing that would “really help us to start having a common language to measure progress on resilience” – comparing it to the Paris temperature goals.

Vulnerable countries also hope that clearer parameters will help unlock more funding for adaptation efforts.

Sounding the alarm over a “yawning gap” in adaptation finance, the UN Environment Programme estimates that developing countries will need to spend between $310 billion and $365 billion a year on resilience measures by 2035 — about 12 times current international public funding levels.

But the outlook for adaptation finance is growing increasingly bleak. The COP26 pledge by developed nations to double funding for developing countries by 2025 appears likely to have been missed, as governments cut overseas spending amid mounting geopolitical tensions and domestic fiscal pressures.

While an official assessment will not be available until 2027, the LDCs are pushing for a new goal to be set at COP30 to boost adaptation finance to about $120 billion a year by 2030. Manjeet Dhakal, a Nepalese negotiator for the group, said that would be the “bare minimum, or otherwise it will be very difficult for us”.

Where those resources could come from remains to be seen. But Corrêa do Lago told Reuters he hoped to produce a “package of resources” for adaptation with rich countries, multilateral development banks and philanthropic organisations all contributing.

How will fractured geopolitics influence discussions?

Geopolitical tensions linked to wars and growing trade rivalries are inevitably casting a long shadow over the climate agenda and hampering multilateral cooperation.

The most disruptive force – US President Donald Trump’s administration – will not be present on the ground in Belèm, barring a last-minute U-turn. The White House told several media outlets that no high-level officials will be sent to the talks, which come a month before the US will officially leave the Paris Agreement.

Many diplomats are likely breathing a sigh of relief after seeing the US use what some observers described as “bully-boy tactics” to sink a landmark deal to cut emissions in the shipping sector last month.

The Trump administration may not be in the room in Belém, but its shadow is likely to hang over the summit. Laurence Tubiana, a key architect of the Paris Agreement, warned that she has never seen such an aggressive stance against climate policy as that emanating from Washington. “We are really confronted with an ideological battle where climate change is in the package the US government wants to defeat,” she told reporters.

Tubiana added that other countries need to stand up and make COP “a turning point”.

The spotlight is expected to fall primarily on the EU, which will carry the torch for rich countries, and large emerging economies, including China, India and COP30 host Brazil.

For Li Shuo, director of the China Climate Hub at the Asia Society Policy Institute, this year’s summit could mark a “collective graduation ceremony” for Global South countries fast-tracked by the retreat of the US.

“When I look at that part of the world, I’m seeing stronger alignment among many countries between their economic growth and the decarbonisation agenda,” he said.

The EU has been walking a tightrope between trying to reaffirm its climate leadership and grappling with internal discord that has threatened to undermine its credibility.

Tubiana said Europe “must stop patronising” and recognise that “we are all interdependent”. “We cannot execute the green transition without cooperation and help from other countries,” she added. “That means we have to propose ways of working, investing and trading that are truly equitable.”

Echoing her words, Arunabha Ghosh, CEO of the Delhi-based Council on Energy, Environment and Water, said countries need to show a different level of solidarity across the [Global] North and the South.

“We are all under collective siege, and when you are under siege, the more you hunker down together, the better chances you have to survive the real and metaphorical hurricanes,” he told reporters.

Will an Amazon COP turn the tide on deforestation?

When Brazilian President Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva picked the Amazon city of Belèm as the venue for COP30, he wanted to make sure that, for the first time, forests would be literally at the heart of the talks as their crucial role in storing carbon and regulating the climate comes under growing threat.

Global deforestation has not slowed significantly in the four years since countries committed at COP26 to halt and reverse forest loss and degradation by 2030.

Last year, the world lost 8.1 million hectares of forest – an area the size of England – leaving the world 63% off track from meeting that pledge, according to the annual Forest Declaration Assessment. Fires and land clearing for agriculture and other commodities remain the leading causes of deforestation.

How could COP30 start turning this negative trend around? The most highly anticipated initiative falls outside of the negotiations, but is being billed as potentially one of Brazil’s biggest legacies as COP host: the launch of the Tropical Forests Forever Facility (TFFF).

World failing on goal to halt deforestation by 2030, raising stakes for Amazon COP

Acting as an investment fund, the mechanism would invest in financial markets and use some of the expected returns to reward forest-rich nations that manage to keep trees standing. It aims to receive an initial capital of $25 billion from governments, which would then be used to attract $100 billion from private investors.

“Think of a bank that runs normal market operations but that directs its profits not to shareholders but to forests,” said João Paulo de Resende, undersecretary for economic and fiscal affairs at Brazil’s Finance Ministry.

The TFFF’s main strategy is to get cheap money from investors and lend money to emerging economies at much higher interest rates. Emerging market bonds would account for as much as 80% of its investments. Exploiting this arbitrage opportunity should guarantee enough returns to pay back investors and channel cash into forest protection, according to its proponents.

But the mechanics of the fund have come in for criticism, with some analysts saying the fund rests on “a fragile illusion” of free revenues to be harvested from the bond market, where higher yields represent bigger real risks.

Potential donors have also been asking “very tough questions” about the fund’s configuration, one of its promoters told Climate Home’s webinar last month. The UK government was reportedly divided over whether to offer cash for the initiative with the Treasury questioning its costs, Politico reported.

So far, only Brazil and Indonesia have committed money to the TFFF, with each pledging $1 billion. But Lula, who has personally championed the initiative, will be hoping to announce more contributions at the flagship launch event on Thursday.

The post Five big questions hanging over COP30 appeared first on Climate Home News.

Climate Change

Climate change could lead to 500,000 ‘additional’ malaria deaths in Africa by 2050

Climate change could lead to half a million more deaths from malaria in Africa over the next 25 years, according to new research.

The study, published in Nature, finds that extreme weather, rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns could result in an additional 123m cases of malaria across Africa – even if current climate pledges are met.

The authors explain that as the climate warms, “disruptive” weather extremes, such as flooding, will worsen across much of Africa, causing widespread interruptions to malaria treatment programmes and damage to housing.

These disruptions will account for 79% of the increased malaria transmission risk and 93% of additional deaths from the disease, according to the study.

The rest of the rise in malaria cases over the next 25 years is due to rising temperatures and shifting rainfall patterns, which will change the habitable range for the mosquitoes that carry the disease, the paper says.

The majority of new cases will occur in areas already suitable for malaria, rather than in new regions, according to the paper.

The study authors tell Carbon Brief that current literature on climate change and malaria “often overlooks how heavily malaria risk in Africa is today shaped by climate-fragile prevention and treatment systems”.

The research shows the importance of ensuring that malaria control and primary healthcare is “resilient” to the extreme weather, they say.

Malaria in a warming world

Malaria kills hundreds of thousands of people every year. The World Health Organization (WHO) estimates that 610,000 people died due to the disease in 2024.

In 2024, Africa was home to 95% of malaria cases and deaths. Children under the age of five made up three-quarters of all African malaria deaths.

The disease is transmitted to humans by bites from mosquitoes infected with the malaria parasite. The insects thrive in high temperatures of around 29C and need stagnant or slow-moving water in which to lay their eggs. As such, the areas where malaria can be transmitted are heavily dependent on the climate.

There is a wide body of research exploring the links between climate change and malaria transmission. Studies routinely find that as temperatures rise and rainfall patterns shift, the area of suitable land for malaria transmission is expanding across much of the world.

Study authors Prof Peter Gething and Prof Tasmin Symons are researchers at the Curtin University’s school of population health and the Malaria Atlas Project from the The Kids Research Institute, Australia.

They tell Carbon Brief that this approach does not capture the full picture, arguing that current literature on climate change and malaria “often overlooks how heavily malaria risk in Africa is today shaped by climate-fragile prevention and treatment systems”.

The paper notes that extreme weather events are regularly linked to surges in malaria cases across Africa and Asia. This is, in-part, because storms, heavy rainfall and floods leave pools of standing water where mosquitoes can breed. For example, nearly 15,000 cases of malaria were reported in the aftermath of Cyclone Idai hitting Mozambique in 2019.

However, the study authors also note that weather extremes often cause widespread disruption, which can limit access to healthcare, damage housing or disrupt preventative measures such as mosquito nets. These factors can all increase vulnerability to malaria, driving the spread of the disease.

In their study, the authors assess both the “ecological” effects of climate change – the impacts of temperature and rainfall changes on mosquito populations – and the “disruptive” effects of extreme weather.

Mosquito habitat

To assess the ecological impacts of climate change, the authors first identify how temperature, rainfall and humidity affect mosquito lifecycles and habitats.

The authors combine observational data on temperature, humidity and rainfall, collected over 2000-22, with a range of datasets, including mosquito abundance and breeding habitat.

The authors then use malaria infection prevalence data, collected by the Malaria Atlas Project, which describes the levels of infection in children aged between two and 10 years old.

Symons and Gething explain that they can then use “sophisticated mathematical models” to convert infection prevalence data into estimates of malaria cases.

Comparing these datasets gives the authors a baseline, showing how changes in climate have affected the range of mosquitoes and malaria rates across Africa in the early 21st century.

The authors then use global climate models to model future changes over 2024-49 under the SSP2-4.5 emissions pathway – which the authors describe as “broadly consistent with current international pledges on reduced greenhouse gas emissions”.

The authors also ran a “counterfactual” scenario, in which global temperatures do not increase over the next 25 years. By comparing malaria prevalence in their scenarios with and without climate change, the authors could identify how many malaria cases were due to climate change alone.

Overall, the ecological impacts of climate change will result in only a 0.12% increase in malaria cases by the year 2050, relative to present-day levels, according to the paper.

However, the authors say that this “minimal overall change” in Africa’s malaria rates “masks extensive geographical variation”, with some areas seeing a significant increase in malaria rates and others seeing a decrease.

Disruptive extremes

In contrast, the study estimates that 79% of the future increase in malaria transmission will be due to the “disruptive” impacts of more frequent and severe weather extremes.

The authors explain that extreme weather events, such as flooding and cyclones, can cause extensive damage to housing, leaving people without crucial protective equipment such as mosquito nets.

It can also destroy other key infrastructure, such as roads or hospitals, preventing people from accessing healthcare. This means that in the aftermath of an extreme weather event, people face a greater risk of being infected with malaria.

The climate models run by the study authors project an increase in “disruptive” extreme weather events over the next 25 years.

For example, the authors find that by the middle of the century, cyclones forming in the Indian Ocean will become more intense, with fewer category 1 to category 4 events, but more frequent category 5 events. They also find that climate change will drive an increase in flooding across Africa.

The study finds that without mitigation measures, these disruptive events will drive up the risk of malaria – especially in “main river systems” and the “cyclone-prone coastal regions of south-east Africa”.

Between 2024 and 2050, 67% of people in Africa will see their risk of catching malaria increase as a result of climate change, the study estimates.

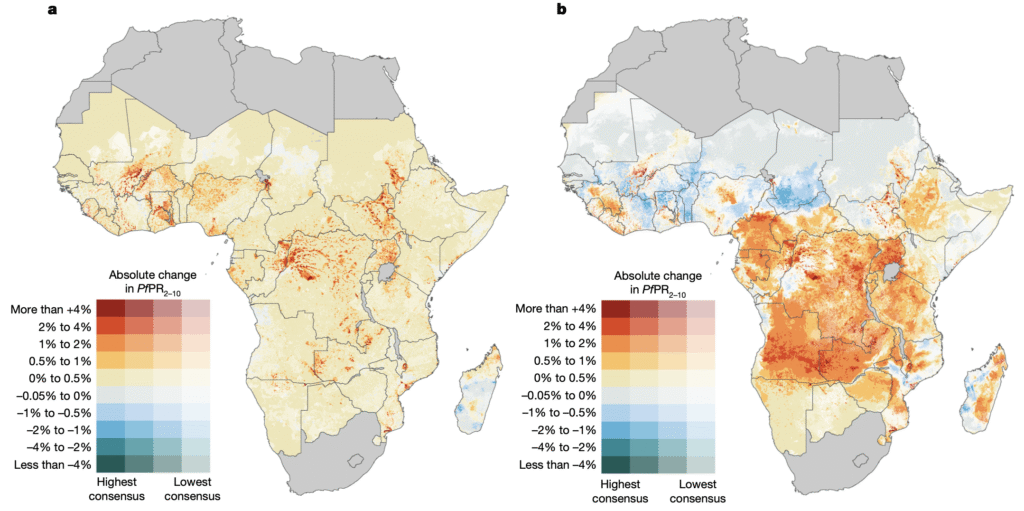

The map below shows the percentage change in malaria transmission rate in the 2040s due to the disruptive impacts of climate change alone (left) and a combination of the disruptive and ecological impacts (right), compared to a scenario in which there is no change in the climate. Red and yellow indicate an increase in malaria risk, while blue indicates a reduction.

Colours in lighter shading indicate lower model confidence, while stronger colours indicate higher model confidence.

The maps show that the “disruptive” effects of climate change have a more uniform effect, driving up malaria risk across the entire continent.

However, there is greater regional variation when these effects are combined with “ecological” drivers.

The authors find that warming will increase malaria risk in regions where the temperature is currently too low for mosquitoes to survive. This includes the belt of lower latitude southern Africa, including Angola, southern Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC) and Zambia, as well as highland areas in Burundi, eastern DRC, Ethiopia, Kenya and Rwanda.

Meanwhile, they find that warming will drive down malaria transmission in the Sahel, as temperatures rise above the optimal range for mosquitoes.

Rising risk

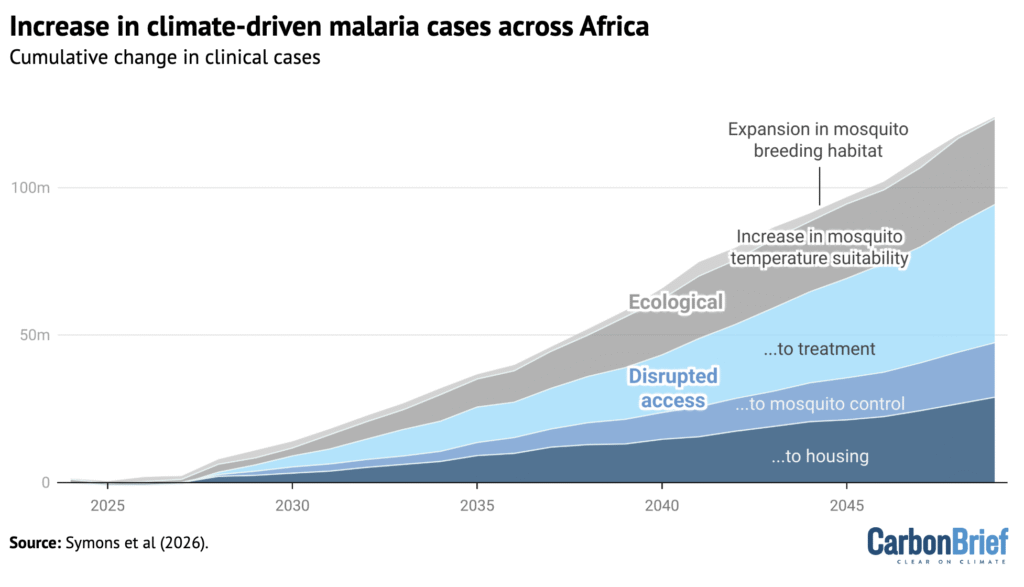

The combined “disruptive” and “ecological” impacts of climate change will drive an additional 123m “clinical cases” of malaria across Africa, even if the current climate pledges are met, the study finds.

This will result in 532,000 additional deaths from malaria over the next 25 years, if the disease’s mortality rate remains the same, the authors warn.

The graph below shows the increase in clinical cases of malaria projected across Africa over the next 25 years, broken down into the different ecological (yellow) and disruptive (purple) drivers of malaria risk.

However, the authors stress that there are many other mechanisms through which climate change could affect malaria transmission – for example, through food insecurity, conflict, economic disruption and climate-driven migration.

“Eradicating malaria in the first half of this century would be one of the greatest accomplishments in human history,” the authors say.

They argue that accomplishing this will require “climate-resilient control strategies”, such as investing in “climate-resilient health and supply-chain infrastructure” and enhancing emergency early warning systems for storms and other extreme weather.

Dr Adugna Woyessa is a senior researcher at the Ethiopian Public Health Institute and was not involved in the study. He tells Carbon Brief that the new paper could help inform national malaria programmes across Africa.

He also suggests that the findings could be used to guide more “local studies that address evidence gaps on the estimates of climate change-attributed malaria”.

Study authors Symons and Gething tell Carbon Brief that during their study, they interviewed “many policymakers and implementers across Africa who are already grappling with what climate-resilient malaria intervention actually looks like in practice”.

These interventions include integrating malaria control into national disaster risk planning, with emergency responses after floods and cyclones, they say. They also stress the need to ensure that community health workers are “well-stocked in advance of severe weather”.

The research shows the importance of ensuring that malaria control and primary healthcare is “resilient” to the extreme weather, they say.

The post Climate change could lead to 500,000 ‘additional’ malaria deaths in Africa by 2050 appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate change could lead to 500,000 ‘additional’ malaria deaths in Africa by 2050

Climate Change

Court rules Netherlands is not doing enough to meet 1.5C goal and protect Bonaire

A court in the Netherlands has ruled that the government’s emissions-cutting and adaptation policies discriminated against and failed to protect citizens of the Dutch Caribbean island of Bonaire from climate change, in violation of the European Convention of Human Rights (ECHR).

In a case brought by Greenpeace, the Hague District Court ruled the government breached Bonaire islanders’ right to a private and family life and discrimininated against them by drawing up policies to adapt Bonaire to climate change later and less systematically than they did for the European part of the Netherlands, despite the islands being more vulnerable to climate change.

Onnie Emerenciana, a farmer plaintiff in the case and one of the 26,000 residents in the Caribbean island, celebrated the decision, saying that the Dutch government can no longer ignore Bonaire’s islanders.

“The court is drawing a line in the sand,” he said, “our lives, our culture, and our country are being taken seriously. The State can no longer look the other way. The next step is to free up funding and expertise for concrete action plans to protect our island. We truly have to do this together; Bonaire cannot solve this alone.”

The Dutch island is located off the Venezuelan coast in the Southern Caribbean, an area that is highly prone to hurricanes, extreme heat and sea level rise. The World Bank estimates that Bonaire could lose up to 12% of its GDP to tropical storms.

ClientEarth fundamental rights lawyer Vesselina Newman said the judgement was “totally groundbreaking” as “it’s the first successful national adaptation case of this scale. The ruling, based on discrimination against the inhabitants of Bonaire, is significant, and will surely open doors for a host of comparable cases around the world – in particular other Global North countries with overseas territories.”

To comply with the convention and the Paris Agreement, the court said the government must submit a new binding emissions-cutting target, which includes international aviation and shipping, for 2030 and other interim targets on the way to net zero by 2050. The current 55% on 2019 levels target is non-binding and, as the court noted, the government accepts it is “highly unlikely” to meet it.

Rebuke to rich nations

Wealthy nations have argued that their climate targets are compatible with the Paris Agreement goal to limit global warming to 1.5C because they plan to reduce emissions faster than the necessary global average. But the court in The Hague ruled Dutch climate policy “does not make an equitable contribution” to meeting this goal.

The panel of three judges ruled that the Netherlands has emitted more than its fair share carbon through its historic emissions, and has not explained how it is “equitable” that the country’s climate plan allows for higher emissions per person than the global average.

The ruling added that, by not including international aviation and shipping, the Dutch and EU emissions reduction targets are “lower than the UN minimum standards” for developed countries.

Most countries’ climate targets do not include international aviation and shipping, arguing that they should be dealt with globally under the International Civil Aviation Organisation (ICAO) and International Maritime Organisation (IMO).

The judges also criticised the government’s adaptation policies as “there is still no climate adaptation plan or integrated climate adaptation policy for Bonaire, even though it has been known for three decades that the island is particularly vulnerable to the negative effects of climate change”. But it said there was still time for adaptation goals under the UN climate regime, which are mostly for 2030, to be met.

Judges order review of climate plan

The ruling gives 18 months to the Dutch government to establish binding targets, enshrined in national legislation, that reduce greenhouse gas emissions in the whole economy. It also ordered the government to develop an adaptation plan for Bonaire that can be implemented by 2030.

Dutch climate minister Sophie Hermans said in a statement that the court delivered a “ruling of significance” and that the government would carefully review it. The ruling could still be appealed.

The Netherlands has long positioned itself as a climate leader on the global stage and is currently leading a global coalition to phase out fossil fuel subsidies and co-chairing an upcoming conference on phasing out fossil fuels in the Colombian city of Santa Marta.

After elections in October 2025, the government which will respond to the ruling is likely to be liberal Rob Jetten. He was environment minister in the previous government and personally promoted the launch of the coalition against fossil fuel subsidies at COP28 in 2023. “My message to Rob Jetten : bring this ruling to the cabinet’s negotiating table tonight,” said Greenpeace Netherlands managing director Marieke Vellekoop.

The court case builds upon the 2024 ruling of the ECHR that the Swiss government breached older Swiss women’s right to a private and family life by not doing enough to cut emissions. Other ECHR members – most of which have similar or less ambitious climate targets and policies to the Netherlands – include most European nations inside and outside of the EU and Turkiye.

The post Court rules Netherlands is not doing enough to meet 1.5C goal and protect Bonaire appeared first on Climate Home News.

Court rules Netherlands is not doing enough to meet 1.5C goal and protect Bonaire

Climate Change

Cropped 28 January 2026: Ocean biodiversity boost; Nature and national security; Mangrove defence

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter. Subscribe for free here. This is the last edition of Cropped for 2025. The newsletter will return on 14 January 2026.

Key developments

High Seas Treaty enters force

OCEAN BOOST: The High Seas Treaty – formally known as the “biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction”, or “BBNJ” agreement – entered into force on 17 January, following its ratification by 60 states, reported Oceanographic Magazine. The treaty establishes a framework to protect biodiversity in international waters, which make up two-thirds of the ocean, said the publication. For more, see Carbon Brief’s explainer on the treaty, which was agreed in 2023 after two decades of negotiations.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “Cropped” email newsletter. A fortnightly digest of food, land and nature news and views. Sent to your inbox every other Wednesday.

DEEP-SEA MINING: Meanwhile, the US – which is not a party to the BBNJ’s parent Law of the Sea – is pushing on with an effort to accelerate permitting for companies wanting to hunt for deep-sea minerals in international waters, reported Reuters. The newswire described it as a “move that is likely to face environmental and legal concerns”.

UK biodiversity probe

SECURITY RISKS: The global decline of biodiversity and potential collapse of ecosystems pose serious risks to national security in the UK, a report put together by government intelligence experts has concluded, according to BBC News. The report was due to be published last autumn, but was “suppressed” by the prime minister’s office over fears it was “too negative”, said the Times.

COLLAPSE CONCERNS: Following a freedom-of-information (FOI) request, the government published a 14-page “abridged” version of the report, explained the Times. A fuller version seen by both the Times and Carbon Brief looked in detail at the potential security consequences of ecosystem collapse, including shifting global power dynamics, more migration to the UK and the risk of “protests over falling living standards”.

News and views

- OZ BUSHFIRES: Bushfires continued to blaze in Victoria, Australia, amid record-breaking heat, said the Guardian. A recent rapid attribution analysis found that the “extreme” Australian heat in early January was made around five times more likely by fossil-fuelled climate change.

- MERCO-SOURED: On 17 January, the EU signed its “largest-ever trade accord” with the Mercosur bloc of countries – Argentina, Brazil, Paraguay and Uruguay – after 25 years of negotiations, per Reuters. On 21 January, amid looming new US sanctions, EU lawmakers voted to send the pact to the European Court of Justice, which could delay the deal by almost two years, according to the New York Times.

- SOY IT ISN’T SO: Meanwhile, the Guardian reported that UK and EU supermarkets have “urged” traders who had “abandoned” the Amazon soya moratorium to stick to its core principles: “not to source the grain from Amazon land cleared after 2008”.

- WATER ‘BANKRUPTCY’: A new UN report warned that the world is facing irreversible “water bankruptcy” caused by overextracting water reserves, along with shrinking supplies from lakes, glaciers, rivers and wetlands, Reuters reported. Lead author Prof Kaveh Madani told the Guardian that the situation is “extremely urgent [because] no one knows exactly when the whole system would collapse”.

- KRUGER UNDER WATER: Flood damages to South Africa’s Kruger National Park could “take years to repair” and cost more than $30m, said the country’s environment minister, quoted in Reuters. Rivers running through the park “burst their banks” and submerged bridges, with “hippos seen…among treetops”, it added.

- FORESTS VS COPPER: A Mongabay report examined how “community forests stand on the frontline” of critical-minerals mining in the Democratic Republic of the Congo’s copper-cobalt belt.

Spotlight

Nature’s coast guard, with backup

This week, Cropped speaks to the lead author of a new study that looks at how – and where – mangrove restoration can be best supported across the world.

Along Mumbai’s smoggy shoreline, members of the city’s Indigenous Koli community wade through the mangroves at dawn to catch fish. Behind their boats, giant industrial cranes whir to life, building new stretches of snaking coastal highway that blot out the horizon.

Mumbai’s mangrove cover is possibly the highest for any major city. With their tangled, stilt roots, mangrove species serve as a natural defence for a city that experiences storm surges and urban flooding every year. These events disproportionately affect the city’s poor – particularly its fishing communities.

This mangrove buffer is being increasingly threatened, as the city chooses coastal roads and other large development projects over green cover, despite protests. But can green and grey infrastructure coexist to protect vulnerable communities in a warming world?

A new global-scale assessment published last week tallied the benefits of mangrove restoration for flood risk reduction, factoring in future climate change, development and poverty.

It advanced the idea of “hybrid” coastal defence measures. These combine pairing tropical ecosystems with modern, engineered defences for sea level rise, such as dykes and levees.

When Carbon Brief contacted lead author and climate scientist Dr Timothy Tiggeloven of Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam, he was in Kagoshima in Japan, home to the world’s northernmost mangrove forests. Why combine mangroves and dykes? Tiggeloven explained:

“Mangroves are like active barriers: they reduce incoming energy from waves, but they will not stop the water coming in from storms, because water can flow through the branches. But wave energy can still be overtopped. So if you reduce wave energy via mangroves and have dykes behind this, they very much have a synergy together and we wanted to quantify the benefits for future adaptation.”

According to the study, if mangrove-dyke systems were built along flood-prone coastlines, mangrove restoration could reduce damages by $800m a year, with an overall return-on-investment of up to $125bn.

It could also protect 140,000 people a year from flood risk – and 12 times that number under future climate change and socioeconomic projections, the study said.

According to the study, south-east Asia could reap the “highest absolute benefits” from mangrove restoration under current conditions. Countries that could see the “highest absolute potential risk reduction” – considering future climate damages in 2080 – are Nigeria ($5.6bn), Vietnam ($4.5bn), Indonesia ($4.3 bn), and India ($3.8bn), it estimated.

Maharashtra – which Mumbai serves as the state capital for – is one of two subnational regions globally that could reap the largest benefits of restoration.

Tiggeloven emphasised that the goal of the study was to examine how restoration impacts people, “because if we’re looking only at monetary terms, we’re only looking at large cities with a lot of assets”, he told Carbon Brief.

A pattern that his team found across multiple countries was that people with lower incomes are disproportionately living in flood-prone coastal areas where mangrove restoration is suitable. He elaborated:

“Wealthier areas might have higher absolute damages, but poor communities are more vulnerable, because they lack alternatives to easily relocate or rebuild, so the relative impact on their wellbeing is much greater.”

Poorer rural coastal communities with fewer engineered protections, such as sea walls, could benefit the most from restoration as an adaptive measure, the study found. But as the study’s map showed, there are limits to restoration. Tiggoloven concluded:

“We also should be very careful, because mangroves cannot grow anywhere. We need to think ‘conservation’ – not only ‘restoration’ – so we do not remove existing mangroves and make room for other infrastructure.”

Watch, read, listen

DU-GONE: A feature in the Guardian examined why so many dugongs have gone missing from the shores of Thailand.

WILD LONDON: Sir David Attenborough explored wildlife wonders in his home city of London. The one-off documentary is available in the UK on BBC iPlayer.

GREAT BARRIER: A Vox exclusive photo-feature looked at the “largest collective effort on Earth ever mounted” to protect Australia’s Great Barrier Reef.

‘SURVIVAL OF THE SLOWEST’: A new CBC documentary filmed species – from sloths to seahorses – that “have survived not in spite of their slowness, but because of it”.

New science

- Including carbon emissions from permafrost thaw and fires reduces the remaining carbon budget for limiting warming to 1.5C by 25% | Communications Earth and Environment

- Penguins in Antarctica have radically shifted their breeding seasons in response to rising temperatures | Journal of Animal Ecology

- Increasing per-capita meat consumption by just one kilogram a year is “linked” to a nearly 2% increase in embedded deforestation elsewhere | Environmental Research Letters

In the diary

- 31 January: Deadline for inputs on food systems and climate change for a report by the UN special rapporteur on climate change

- 1 February: Costa Rica elections

- 2-6 February: First session of the plenary of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Panel on Chemicals, Waste and Pollution | Geneva

- 2-8 February: Twelfth plenary session of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services | Manchester, UK

- 5 February: Future Food Systems Summit | London

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz. Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 28 January 2026: Ocean biodiversity boost; Nature and national security; Mangrove defence appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Cropped 28 January 2026: Ocean biodiversity boost; Nature and national security; Mangrove defence

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits