The UK should cut its emissions to 87% below 1990 levels by 2040 under its seventh five-yearly “carbon budget”, according to official advice from the Climate Change Committee (CCC).

This target, which includes greenhouse gas emissions from international aviation and shipping, would keep the UK on track for reaching net-zero by 2050, the CCC says.

The committee says electrification is the key to decarbonising the UK economy, with most vehicles shifting to electric and most homes using heat pumps by the middle of the century.

It says there would be small, but vital roles for energy efficiency, behaviour change, carbon removal and technologies, such as carbon capture and storage.

It says reaching net-zero would require significant up-front investment, but would enhance energy security, cut operating costs and reduce bills, by cutting demand for imported fossil fuels.

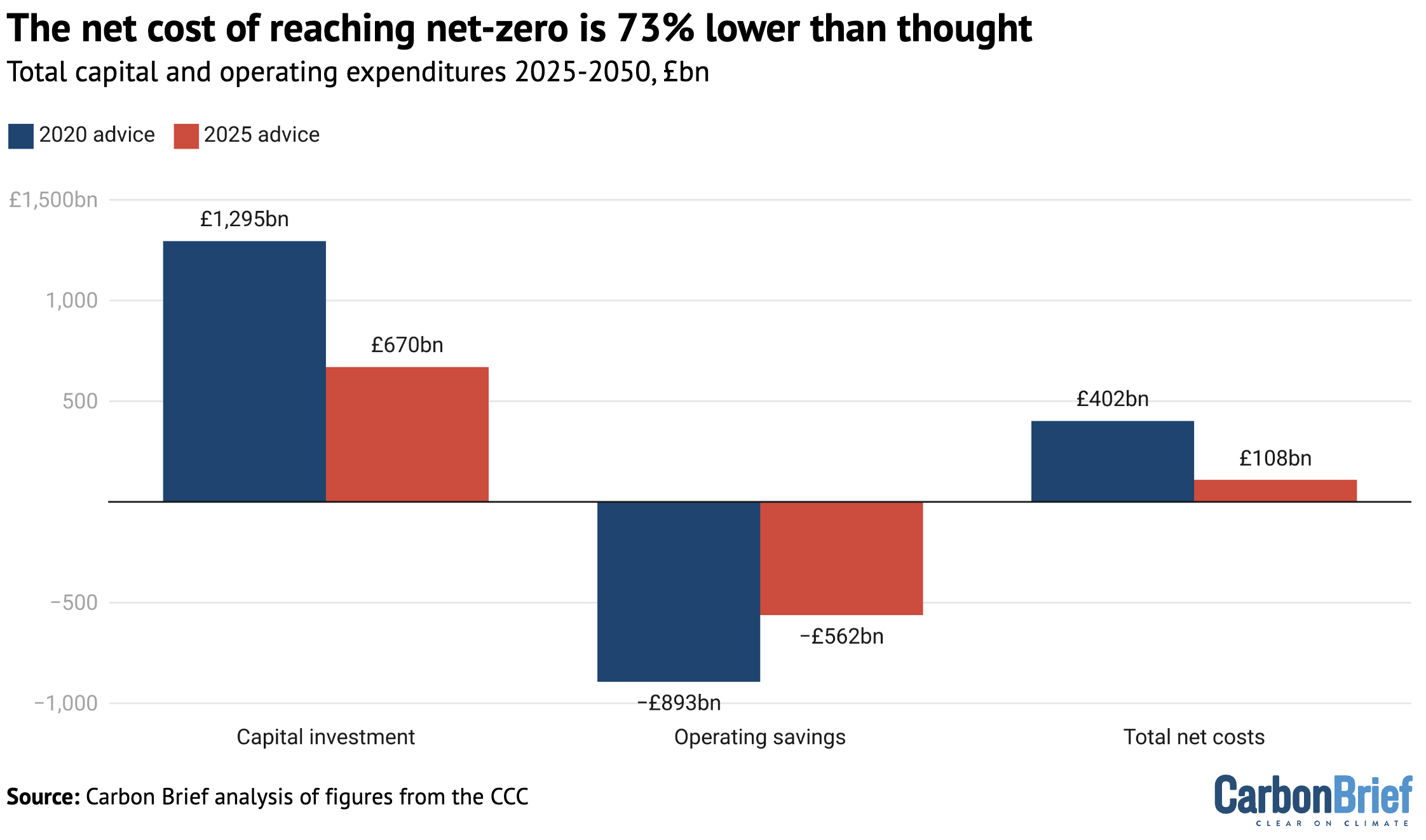

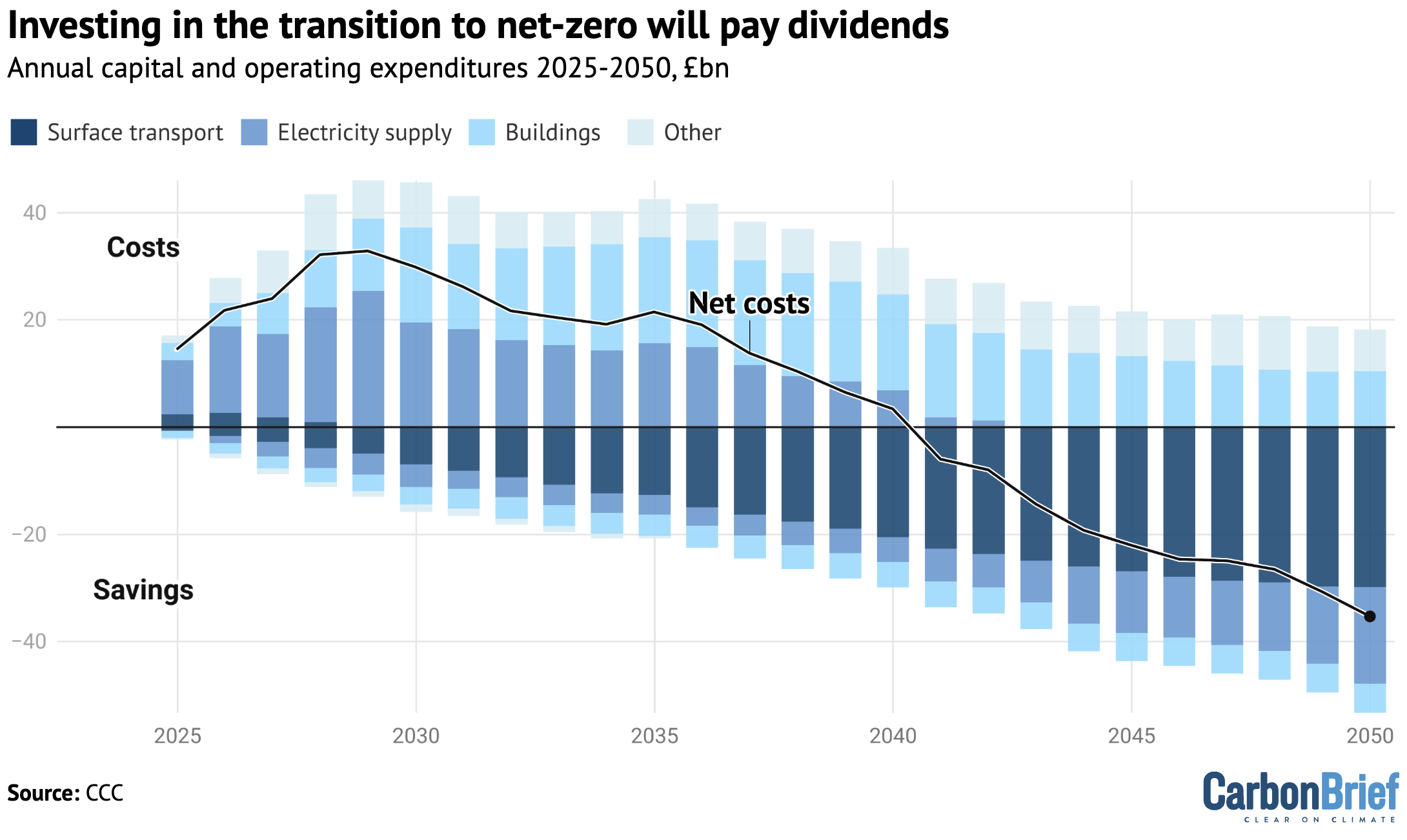

In total, the CCC says the transition would have a net cost of around £108bn out to 2050, which is £4bn per year, or less than 0.2% of GDP. This is 73% lower than previously thought under its sixth carbon budget advice, published in 2020.

Moreover, the transition to net-zero would cut average household energy bills to £700 below today’s levels by 2050 and cut household motoring costs by a similar amount, the CCC says.

The government has until 30 June 2026 to legislate for the seventh carbon budget, which covers the period from 2038-2042.

Previous governments – whether Conservative or Labour – have always followed the CCC’s advice on the level of UK carbon budgets.

- What is the ‘seventh carbon budget’?

- How could the UK cut emissions 87% by 2040?

- What are the costs and benefits of net-zero?

- What new climate policies does the CCC recommend?

- How would each sector need to change by 2040?

- What does the CCC say about imported emissions?

What is the ‘seventh carbon budget’?

The UK’s efforts to tackle global warming are governed by the 2008 Climate Change Act, which was legislated by a cross-party parliamentary consensus of 463 votes to five.

After being amended by the Conservative government in 2019, the long-term target of the act is to cut the UK’s emissions in 2050 to 100% below 1990 levels – usually referred to as “net-zero”.

(The Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) has affirmed that reaching net-zero is the only way to stop global warming from getting worse – and that emissions would need to reach net-zero by 2050 globally to limit the rise in temperatures to 1.5C.)

In addition to the 2050 target, the Act sets a framework for five-yearly “carbon budgets”, which are “stepping stones” for the UK’s emissions along the pathway towards net-zero.

The UK met its first three carbon budgets, covering the 15 years from 2008-2022, and is currently at the mid-point of the fourth carbon budget period for 2023-2027.

Under the Act, the CCC is required to offer advice to government on the level of each carbon budget, 12 years in advance. In doing so, it must take into account a range of factors, including the latest scientific evidence, technological trends, the state of the economy and public finances.

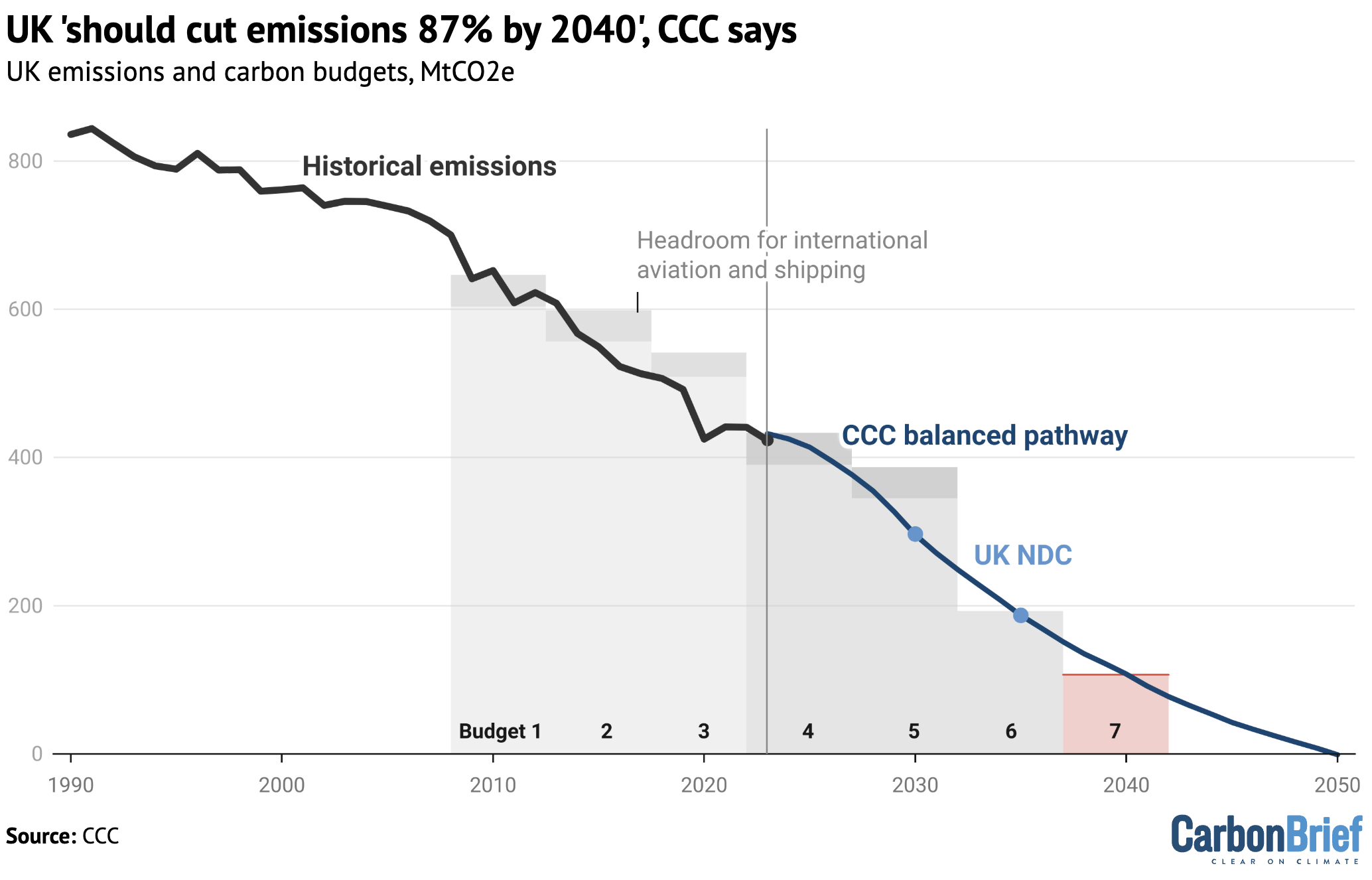

Its advice on the seventh carbon budget, covering 2038-2042, is for the UK to cut its emissions to 87% below the 1990 baseline – equivalent to a three-quarters reduction on current levels.

Specifically, the CCC says emissions should fall from around 400m tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e) in 2023 to just 107MtCO2e on average across 2038-2042.

This is shown in the figure below, alongside previously legislated budgets and the UK’s international climate pledges for 2030 and 2035 under the Paris Agreement.

Note that the sixth and seventh budgets were set in line with the net-zero target, whereas previous budgets were set on a pathway to 80% by 2050, hence the step change.

These budgets also include emissions from international aviation and shipping, whereas previous ones had allowed “headroom” for these emissions. (The CCC notes that the government has yet to reflect this shift in legislation and calls for it to do so, when setting the seventh carbon budget.)

Now that the CCC has offered its advice, the government must pass legislation setting the level of the seventh carbon budget by no later than 30 June 2026.

Previous governments – whether Conservative or Labour – have always followed the advice of the committee. However, the government can choose not to do so, if it explains why.

This legislation is subject to the “affirmative procedure” in parliament, which can reject the government’s proposal. It must be debated and voted through by both houses of parliament.

Notably, the CCC backs a proposal by the former prime minister Rishi Sunak for the government to publish its plan for meeting the seventh carbon budget, before the target is voted on by parliament.

It suggests the government could publish a draft plan ahead of the votes in parliament. (The Climate Change Act requires the government’s final plan for meeting carbon budgets to be published “after” the carbon budget has been set.)

In line with its long-standing position, the CCC says the seventh carbon budget should be met via domestic action “without resorting to international [emissions] credits”.

Note that the CCC’s full methodology report will be published on 21 May 2025, alongside its advice to the devolved administrations of Northern Ireland, Scotland and Wales.

How could the UK cut emissions 87% by 2040?

The CCC says its recommended 87% emissions cut for the seventh carbon budget is “ambitious”, but remains “deliverable provided action is taken rapidly”.

In order to illustrate what it would take to reach this target, the CCC advice includes a “balanced pathway” that extends out to net-zero by 2050.

Speaking to a pre-launch press briefing, CCC chief executive Emma Pinchbeck, who took up the role last November, said this was designed to prove the 87% target was “feasible and deliverable”.

However, she stressed that the committee does not set policy and that it was up to the government to choose its preferred route. (See: What new climate policies does the CCC recommend?)

Still, the balanced pathway offers useful insight into how the UK could reach the 87% target by 2040 – and what the country would look like as a result.

To date, most of the reductions in UK greenhouse gas emissions have come in the power sector thanks to the expansion of renewable energy and the phase-out of coal-fired generation.

By 2040, however, this would need to change significantly, with emissions cuts taking place across every sector of the UK economy. (See: How would each sector need to change by 2040?)

Specifically, the UK would massively reduce emissions from surface transport (86%), building heat (72%), industry (78%) and the power sector (88%), historically the country’s largest polluters.

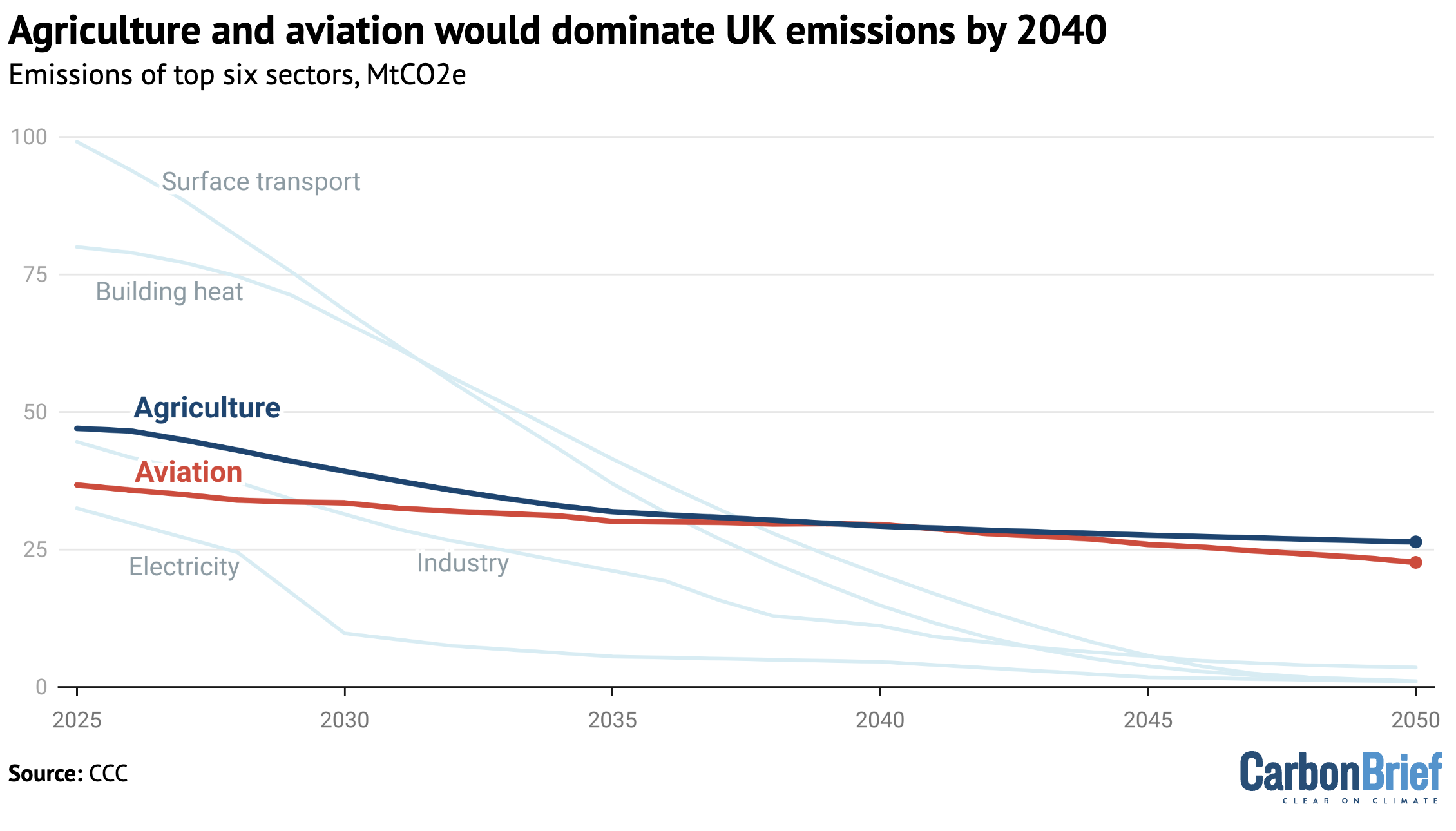

By 2040, aviation and agriculture would be the UK’s largest emitters, shown in the figure below. Even in 2050, these sectors would continue to have significant emissions.

Under the CCC’s net-zero pathway, natural carbon sinks in the land sector would balance out emissions from agriculture, while engineered carbon removals would balance aviation.

While emissions cuts would be needed across the whole economy to meet the seventh carbon budget, the power sector would remain the lynchpin for wider progress. This is because electrification is now seen as the key solution for decarbonising the rest of the economy.

Whereas the sixth carbon budget advice hedged, offering five different routes towards net-zero, the CCC now offers a single balanced pathway built around clean power. The report says:

“In many key areas, the best way forward is now clear. Electrification and low-carbon electricity supply make up the largest share of emissions reductions in our pathway.”

This includes heat pumps in homes and businesses. The CCC says very clearly that there is “no role” for hydrogen heat.

In addition, the CCC now sees a far greater role for electrification of transport, including all HGVs, as well as in heavy industry.

Furthermore, the CCC points to important roles for energy efficiency, such as improved home insulation, and continued gradual changes in behaviour, such as reduced red meat consumption.

Where electrification is not possible, the CCC says other technologies will be needed. This includes bioenergy, synthetic fuels, such as hydrogen or methanol, and the continued use of small amounts of fossil fuels – in “limited circumstances” – with carbon capture and storage (CCS).

(The CCC says: “We cannot see a route to net-zero that does not include CCS.”)

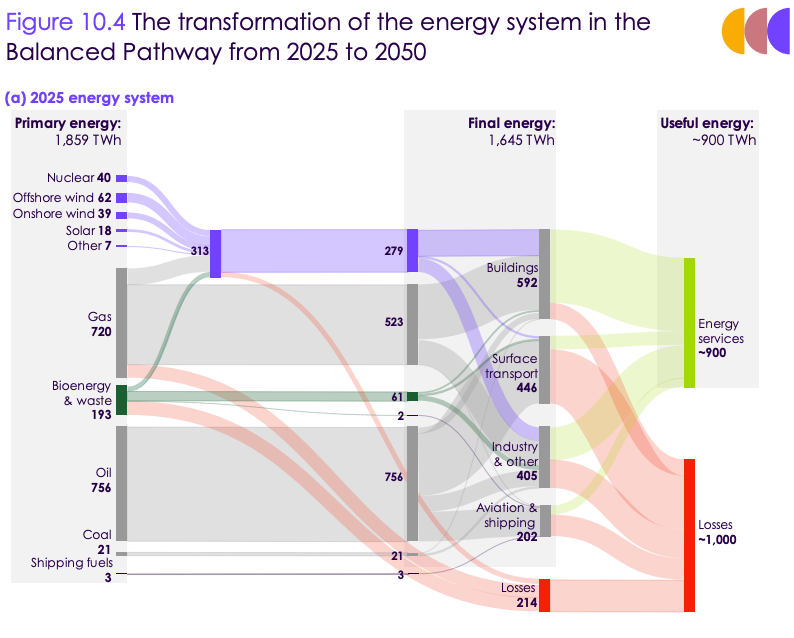

The Sankey diagram below shows how the UK’s energy system looks today – and how it would need to change by 2050, if the seventh carbon budget and net-zero target are to be met.

On the left, each figure shows inputs of “primary energy” into the economy from low-carbon sources or fossil fuels. The central section shows the conversion of these fuels into final energy delivered to consumers, such as electricity or road fuel. The right-hand section shows the useful “energy services” that this final energy is able to provide, such as heat, light or motion (green).

Notably, the energy system would shift away from relying on fossil fuels (grey) towards a much greater use of electricity (blue). Technologies such as heat pumps and electric vehicles are far more efficient than boilers or combustion engines. As a result, the UK would get more useful energy (green) using far less primary energy, thanks to waste heat losses being halved (red).

The huge reductions in fossil-fuel use and related increase in the overall efficiency of the UK system would yield significant economic benefits, the CCC explains, covered in the next section.

The CCC says that the shift to net-zero would cut oil imports tenfold from current levels by 2050 and cut gas imports by two-thirds over the same period.

What are the costs and benefits of net-zero?

The CCC’s advice comes against a backdrop of record global temperatures, with 2024 the first full year more than 1.5C hotter than pre-industrial times and escalating extreme weather impacts.

At the same time, there is growing hostility to climate action from large parts of the UK’s right-leaning media, as well as climate-sceptic, right-wing populist politicians, such as US president Donald Trump.

In addition, Russia’s 2021 invasion of Ukraine and the subsequent spike in fossil-fuel prices continue to cause geopolitical instability – and high energy bills.

The CCC presents the pathway towards net-zero as a solution to all of these problems.

It says reaching net-zero would not only end the UK’s contribution to climate change, but would also reduce high energy bills and energy insecurity caused by reliance on fossil-fuel imports.

Moreover, it says the up-front investment needed to reach net-zero is much smaller than thought in its previous 2020 advice, bringing the net cost down to just £108bn over 25 years (0.2% of GDP).

The new 2025 estimate of the net cost of reaching net-zero by 2050 is shown by the red bars in the figure below, compared with the previous sixth carbon budget advice from 2020 (blue). The chart also shows the capital investments and operational savings that make up the net cost overall.

Significantly, the new advice halves the CCC’s previous estimate published in 2020 of the capital investments needed to hit net-zero, from £1.3tn over 2025-2050 to £0.7tn. The earlier figure has been cited repeatedly by those attempting to undermine support for net-zero.

(Those attacking climate policy rarely mention the operational savings that would be delivered by investing in low-carbon technologies as a result of buying less oil and gas. Even under the earlier 2020 advice, the net cost of net-zero was £0.4tn, or around 0.6% of GDP.)

Notably, the large majority of the investment needed to reach net-zero would come from the private sector, according to the CCC, as long as the “right incentives” are in place.

It says that publicly funded outlays would need to range from £6-23bn per year out to 2035 and would never exceed 2% of government spending overall. Pinchbeck told a press briefing:

“We think 65-90% of the capital required is coming from the private sector…Wwhat the government needs to do is create the enabling environment to get that capital to move.”

There are several reasons for the fall in estimated net costs, with the largest contribution coming from the CCC assuming that EVs will be cheaper to buy than petrol equivalents within a few years.

This means that decarbonising the road transport sector would be cheaper than sticking with combustion engine cars, even before considering the considerable operational cost savings.

The figure below shows how the up-front investment needed for net-zero would deliver substantial operational cost savings from the 2040s under the CCC’s balanced pathway.

The figure shows that the largest capital cost would come in the buildings sector, where it expects the upfront cost of heat pumps could remain higher than gas boilers even in 2050.

As a result – and despite lower running costs, if electricity prices are cut in line with its advice – the CCC says the government would need to support households shifting to heat pumps.

In total, the CCC says that household energy bills for heat and power could fall to £700 below 2025 levels by 2050. In addition, it says that motoring bills would fall by another £700.

The advice considers distributional impacts for the first time, looking at how different types of households would be affected by the shift to net-zero. If the government reduces electricity costs then most types of households would see a cost saving. The exception to this would be homes unable to switch to heat pumps and using less efficient “resistive” heating instead.

In a pre-launch press briefing, Pinchbeck addressed those arguing against the transition:

“If you are an elected representative who is hostile to renewables, heat pumps, electric vehicles, what our numbers say is you are also hostile to your constituents saving £700 on their energy bill and [another] £700 on their fuel bill through making those changes.”

What new climate policies does the CCC recommend?

The CCC says that achieving its recommended targets will rely on a “combination of markets, government support and choices by the public”.

It stresses that a “stable” and “consistent” set of climate policies would help to provide confidence to people and businesses during the net-zero transition. It adds that certain policies are also needed to “provide financial incentives, where necessary”.

Under the previous government, the committee repeatedly warned that the UK required more comprehensive climate policies. This shortfall was exacerbated by the Conservative leadership’s decision in 2023 to roll back some of its own net-zero policies.

The CCC has also warned that the Labour government, which was elected last year, must take urgent action to “make up lost ground”.

However, the committee’s new recommendations are less prescriptive about specific policies than its previous advice. (The last carbon budget advice, in 2020, was accompanied by an additional 209-page report titled: “Policies for the sixth carbon budget and net-zero.”)

Speaking to journalists at a press briefing, interim CCC chair Prof Piers Forster explained this new approach:

“We went back to the Climate Change Act and we did have a look at our core responsibility within that act – and that is to give government and parliament the very best non-partisan advice possible…It’s not up to us to make the policy, it’s up to government.”

Nevertheless, the new report still includes 43 “priority recommendations” for the government to support the delivery of the proposed seventh carbon budget. There are “seven core themes that underpin most of these recommendations”, which are:

- “Making electricity cheaper”: Rebalancing prices to remove policy levies from electricity bills could incentivise people and businesses to choose low-carbon technologies, the CCC says.

- “Removing barriers”: Processes and rules around planning, consenting and regulatory funding – including those covering grid infrastructure – “need to enable rapid deployment of low-carbon technologies”, according to the CCC.

- “Providing certainty”: For technologies where markets have already “locked into a solution”, the committee says the government should introduce clear policies for phasing out old technologies and scaling up new ones.

- “Supporting households to install low-carbon heating”: Government support is specifically needed to tackle the high up-front costs of heat-pump installations and other barriers such as “misconceptions”, the report states.

- “Setting out how government will support businesses”: The CCC says businesses, including farmers, need clarity on how much government support they will receive and how much to rely on market mechanisms, such as the UK emissions trading scheme (ETS), to decarbonise.

- “Enabling the growth of skilled workforces and supporting workers in the transition”: Government, businesses and affected communities should plan for changes in some industries, plus ensure that there is a workforce available to enable the net-zero transition, according to the CCC.

- “Implementing an engagement strategy”: Finally, the committee stresses the importance of the government providing ”clear information to households and businesses”, including on the benefits of low-carbon choices.

There is some more specific guidance within these recommendations. This includes confirming that there will be no role for hydrogen in heating, no new properties connected to the gas grid from 2026 and no extended contracts for large biomass plants operating extensively beyond 2027.

CCC lead analyst Dr James Richardson tells Carbon Brief that such specificity reflects the committee’s certainty on some policies. He contrasts this with rebalancing electricity pricing, which the committee thinks is necessary, but could be achieved in a number of ways.

The report also calls for the government to publish its long-awaited land-use framework, which it is currently consulting on, as well as a common sustainability framework for biomass, which would support bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS).

More broadly, the CCC recommends that the government should produce a draft set of proposals and policies for delivering the seventh carbon budget. This would “aid parliamentary scrutiny in the setting of the budget level”, it says (See: What is the ‘seventh carbon budget’?).

It also says the government should introduce indicators to ensure emissions cuts are on track, as well as “contingency measures that could make up any shortfalls”.

Beyond emissions cuts, the CCC also calls for the government to strengthen the implementation of its third national adaptation plan, and introduce “clear objectives and measurable targets” across all departments.

How would each sector need to change by 2040?

The CCC lays out a detailed breakdown of how each sector in the UK economy could reduce its emissions in the coming years.

This analysis aligns with its balanced pathway, which reduces overall emissions in line with the seventh carbon budget and, ultimately, achieves net-zero by 2050.

The committee also details key metrics, from electric cars on the road to average meat consumption, and how they change on this trajectory.

Surface transport

Road and rail transport has been the sector with the highest emissions in the UK for a decade, currently accounting for around a quarter of the nation’s emissions.

It is also the sector that would see the biggest dip in emissions in the CCC’s pathway – dropping by 86% from 103MtCO2e in 2023 to 15MtCO2e in 2040.

As the chart below shows, that drop is driven predominantly by the electrification of cars and vans. This accounts for 72% of the emissions savings out to 2040.

Another 12% comes from zero-emission heavy-goods vehicles (HGVs) and 3% comes from other zero-emissions vehicles, such as buses and motorcycles. Most of these vehicles are also expected to be electric.

In total, by 2040 some 80% of cars, 74% of vans and 63% of HGVs would be electric, under the CCC’s balanced pathway.

The uptake of electric vehicles modelled by the CCC is faster than the trajectory in the government’s legally binding zero-emission vehicle (ZEV) mandate. The committee says this is achievable, noting that “there has been strong early electric vehicle growth in the UK”.

In the CCC’s pathway, the electric-vehicle transition is “propelled by the falling cost of batteries”, which allows electric cars to match the purchase price of petrol and diesel cars by 2026-2028.

The expansion of public charging points also plays an important role. The committee says there should also be efforts to make local public charging “more comparable to charging at home”.

The Labour government pledged to reintroduce the 2030 phaseout date for new petrol and diesel cars, which was delayed by Rishi Sunak’s Conservative government.

The CCC says the government should enact this pledge, as well as clarifying its position on similar phaseout dates for vans and HGVs with combustion engines.

Moreover, the committee says the government should consider including plug-in hybrid electric vehicles (PHEVs) in the phaseout. It says “ambitious targets” for the ZEV mandate would be needed beyond 2030, if PHEVs are not included in the ban.

The committee stresses that electric cars could also be included in a public information campaign to communicate their cost-saving potential. People have been “misinformed about battery longevity and electric vehicle lifecycle emissions”, the report says.

In addition, the committee says there is a need for a suite of policies, subsidies and regulatory mechanisms to scale up sales of electric vans and HGVs.

The CCC sees little or no role for hydrogen in any form of transport.

Another sizable chunk of emissions savings, amounting to 9% by 2040, comes from the replacement of 7% of car journeys with buses, walking and cycling. This is an “ambitious assumption” that the committee says is based on evidence from Germany and the Netherlands.

To achieve this shift, the committee says the government should “provide local authorities with long-term funding and powers”.

The CCC emphasises that many of the biggest benefits associated with net-zero will come from a switch to low-carbon forms of transport. For example, people will save money because electric cars are cheaper to run.

However, this also applies to the £2.4-8.2bn annual “co-benefits” that will accrue across the economy by 2050. Most of these benefits, including better air quality, fewer road accidents and reduced congestion, result from a switch to electric cars or away from cars altogether.

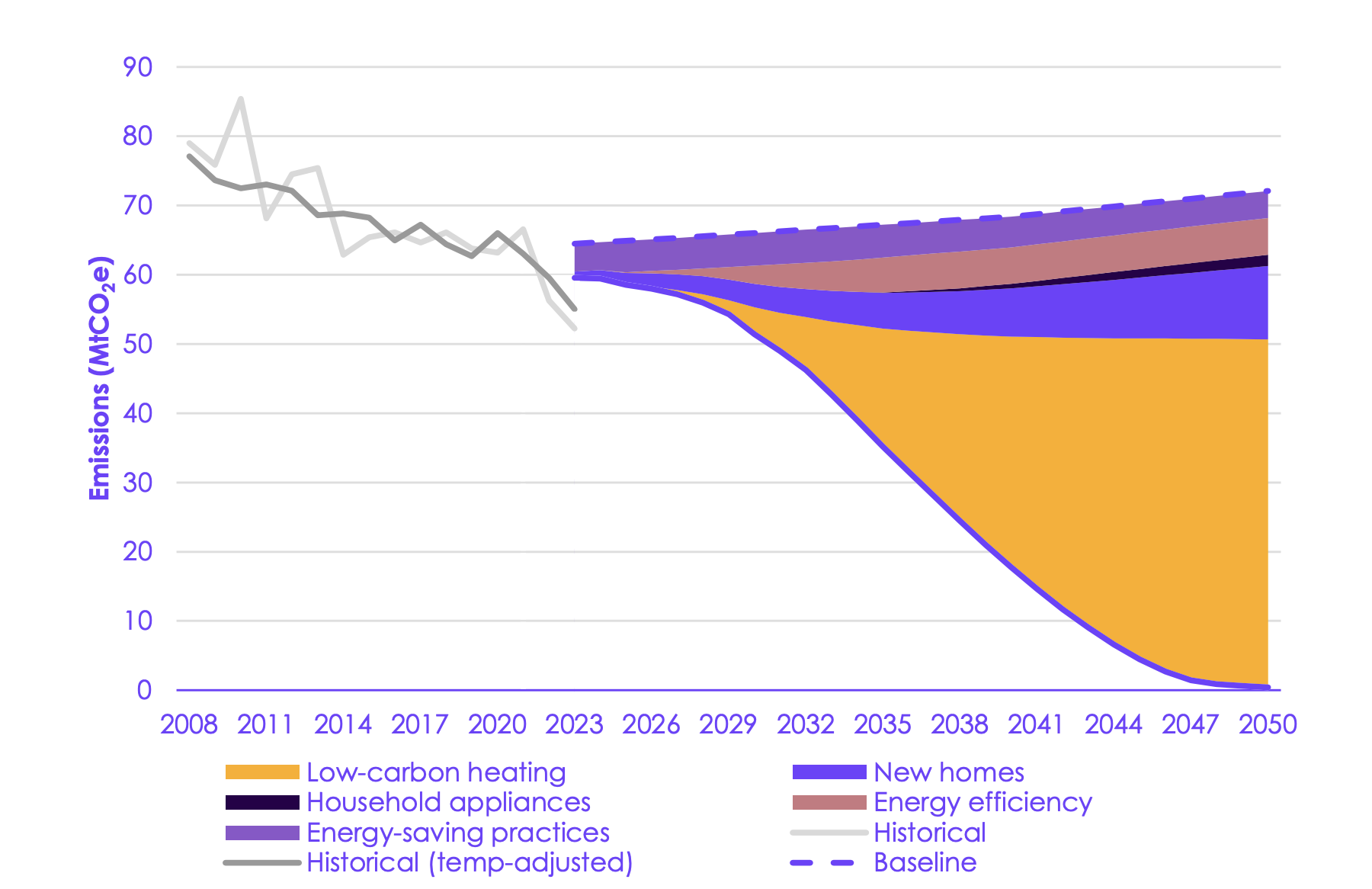

Building heat

Heat pumps are going to drive the biggest reduction in heating emissions in the UK, while there is “no role” for hydrogen in the sector, according to the CCC.

Residential buildings are currently the second highest emitting sector in the UK, accounting for 12% of emissions (52MtCO2e) in 2023.

The largest source of emissions within the sector is fossil fuels for space heating and hot water, representing 96% of emissions. Of this, 80% comes from gas, while oil and liquefied petroleum gas make up another 12%.

Emissions in the sector have gradually decreased since the early 2000s, driven by policies to improve the efficiency of heating technologies and invest in energy efficiency. A sharp decrease in emissions since 2021 has been caused by high gas prices and mild winters.

Under the CCC’s balanced pathway, emissions from residential heat would fall to 66% below 2023 levels by 2040. By the middle of the century, the sector could almost totally decarbonise.

Building emissions fall faster in the 2030s in the seventh carbon budget advice than in the sixth carbon budget report, predominantly due to the use of “S-curves” for the pickup of heat pumps.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, the CCC’s director of analysis Dr James Richardson says that, while the UK is behind other European countries in the installation of heat pumps, the advantage of being such a “laggard” is that it can learn from other markets, making the modelling “more precise”.

While there will be a limited role for other electric-heating technologies, there is no role for hydrogen heating in residential buildings, the CCC says.

Speaking during a briefing, Richardson highlighted the weight of research showing that hydrogen heat would be expensive and challenging to roll out. He said:

“Hydrogen is a limited resource. It’s quite costly to make and you need quite a lot of equipment that doesn’t already exist, so we can’t just magic it out of the air, as it were, and using it for heating is not a particularly efficient use of hydrogen.”

The share of existing homes with low-carbon heating increases from 8% in 2023 to 68% in 2040 under the CCC’s balanced pathway, including the share of homes with a heat pump growing from sound 1% to 52% over the same time period.

This would mean 75% of low-carbon heating systems installed by 2040 are heat pumps, with 94% of these being air-source heat pumps, the advice suggests.

In the CCC’s pathway, the rate of heat pump installations grows from 60,000 in 2023 to nearly 450,000 in 2030, and then 1.5m by 2035. While this represents a rapid increase, it falls short of the government’s target of 600,000 installations a year by 2028.

Other forms of low-carbon heating systems expected to grow are: communal heat pumps (3% by 2040); low-carbon heat networks (9%); and direct electric heat (13%).

In addition to getting rid of their boilers, most homes would also receive small energy efficiency improvements and 17% would see big efficiency improvements installed by 2050.

Energy efficiency would be responsible for 10% of emissions reductions in 2040, according to the CCC.

The committee’s balanced pathway assumes all new homes would be built to be highly efficient and have low-carbon heating systems. These represent 14% of emissions reductions in 2040.

There are substantial upfront capital-cost requirements for lowering emissions within the residential sector, but energy efficiency measures and low-carbon heating systems have additional social benefits beyond long-term savings. The CCC estimates the co-benefits of its pathways at £650m by 2040.

The transition represents an opportunity to reduce fuel poverty in the UK, it says, reducing the number of households in fuel poverty by 77% by 2050 compared to 2025.

To facilitate this transition, the CCC recommends electricity bills be made cheaper by removing levies and other policy costs, as well as decarbonising the electricity system. (See: Electricity below.)

Additionally, the government should confirm that there will be no role for hydrogen in home heating, reinstate regulations that all heating systems installed by 2035 are low carbon and provide long-term funding for energy efficiency, amongst other policy moves.

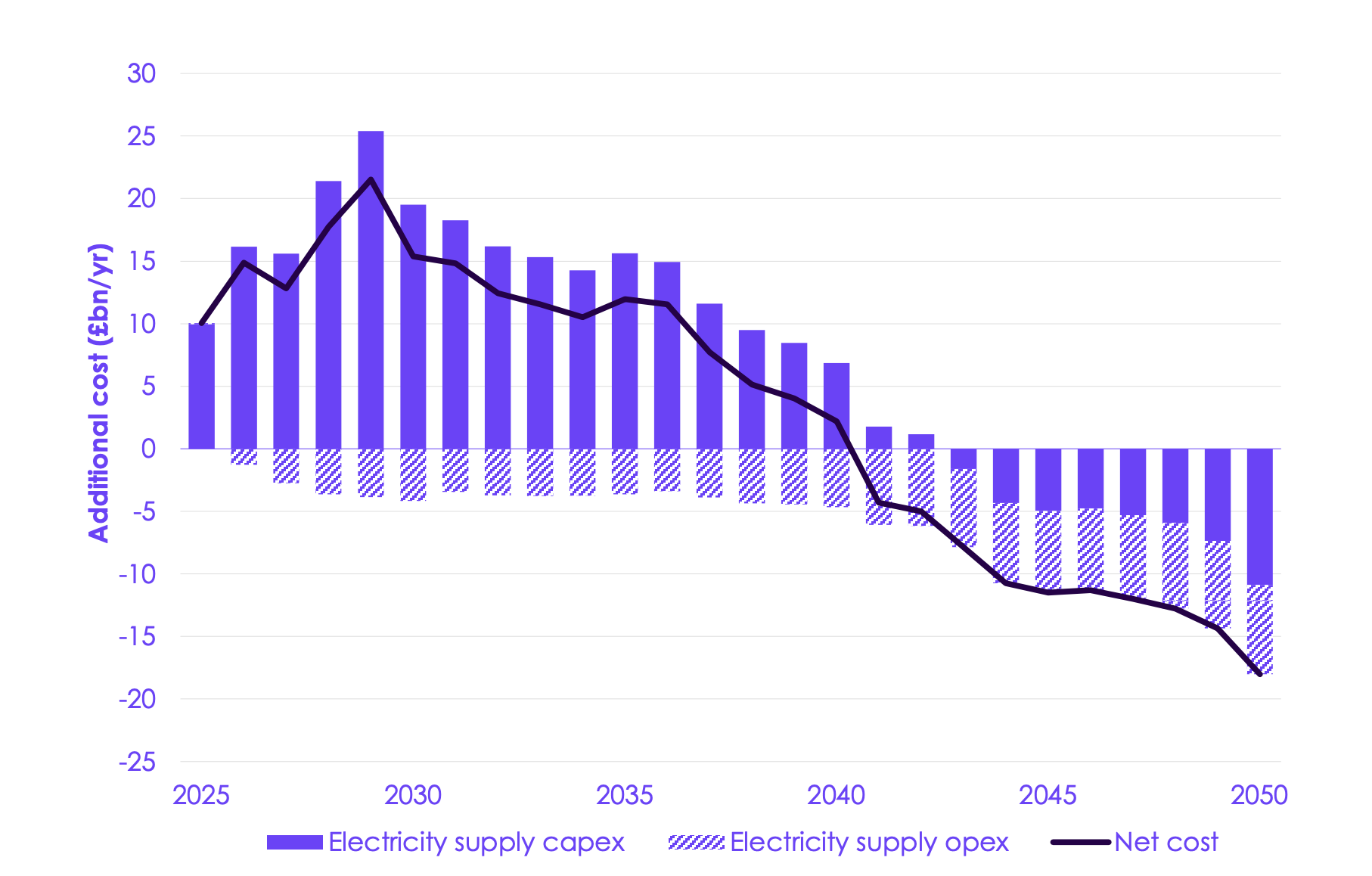

Electricity

Emissions from the electricity sector have fallen by 81% since 1990, to 38MtCO2e in 2023, according to the CCC.

The majority of this decrease has happened since 2012 due to the phase-out of coal – the UK’s last coal-fired power plant closed last year – and an increase in low-carbon generation.

Between 2010 and 2023, the share of generation from wind and solar rose from 3% to 34%, helping to displace coal and gas, the CCC notes. The remaining emissions in the electricity sector are largely from unabated gas, which accounted for 30% of UK generation in 2023.

Under the CCC’s balanced pathway, emissions from electricity supply fall by 88% to just 5MtCO2e in 2040. The committee notes that the sector can almost completely decarbonise by 2050.

Over the next 25 years, demand for electricity is expected to more than double, from 274 terawatt hours (TWh) in 2023 to 692TWh in 2050. This is due to the increase in electric vehicles, heat pumps and other electric technologies to decarbonise other sectors.

Renewable generation would make up 80% of generation in 2040. This would require the deployment of offshore wind – which would be the “backbone” of the system – to increase from around 1-2 gigawatts (GW) per year to 5.7GW per year out to 2030, before then maintaining a rate of 4GW per year, on average, out to the middle of the century.

Onshore wind would require an average deployment rate of 0.8GW per year, peaking at 1.9GW in 2030 – this is comparable to its historical peak of 1.8GW in 2017. Solar would need an average deployment rate of 3.4GW per year – below the historical peak seen in 2015 of 4.1GW.

The CCC says there are several potential barriers to deployment, including planning, grid connections and supply-chain bottlenecks.

The CCC expects “firm power” from nuclear and bioenergy with carbon capture and storage (BECCS) to make up 13% of generation in 2040. This would require an additional 5GW of nuclear capacity to be built, in addition to the Hinkley C new nuclear plant under construction in Somerset.

“Dispatchable” generation from gas with CCS or hydrogen-fired turbines would make up the final 7% of the mix, but with a large capacity of 38GW by 2050. The electricity network would also need to be expanded “at pace” to ensure that the growing demand for electricity is enabled.

The electricity system of the future would include much more grid storage, the CCC says, with 35GW of short-duration batteries by 2050, more than a ten-fold increase on 2023 levels. A range of medium-duration technologies are also expected to be rolled out, with 7GW on the grid by 2050.

Smart demand flexibility systems would need to be expanded and interconnectors to increase in capacity from around 10GW today to 28GW by 2050.

Together with storage, these would help manage grid security, with the CCC modelling a one-in-20 “adverse weather year” that includes wind droughts, to ensure the system would remain reliable.

The CCC states that these changes would allow the emissions intensity of electricity – its emissions per unit of generation – to fall by 95% by 2040 and 99% by 2050.

The growth of cheap renewable energy would displace unabated gas generation, resulting in operational savings, the CCC says, as shown in the chart below. In order for the effect of this to be felt by consumers, policy costs should be rebalanced away from electricity bills, the CCC adds.

Despite the “significant investment” required to decarbonise and expand the electricity system under the CCC’s pathway, the underlying costs of electricity supply fall compared to the baseline.

The shift provides a number of co-benefits as well, including industrial opportunities, increasing energy security by reducing reliance on volatile international prices and improving air quality.

To meet the requirements of the balanced pathway, the CCC calls on the government to ensure the funding and auction design for the next contracts-for-difference subsidy auctions are sufficient.

It also calls for reform processes and rules around planning and consenting of new projects, as well as clarity around electricity market arrangement, amongst other actions.

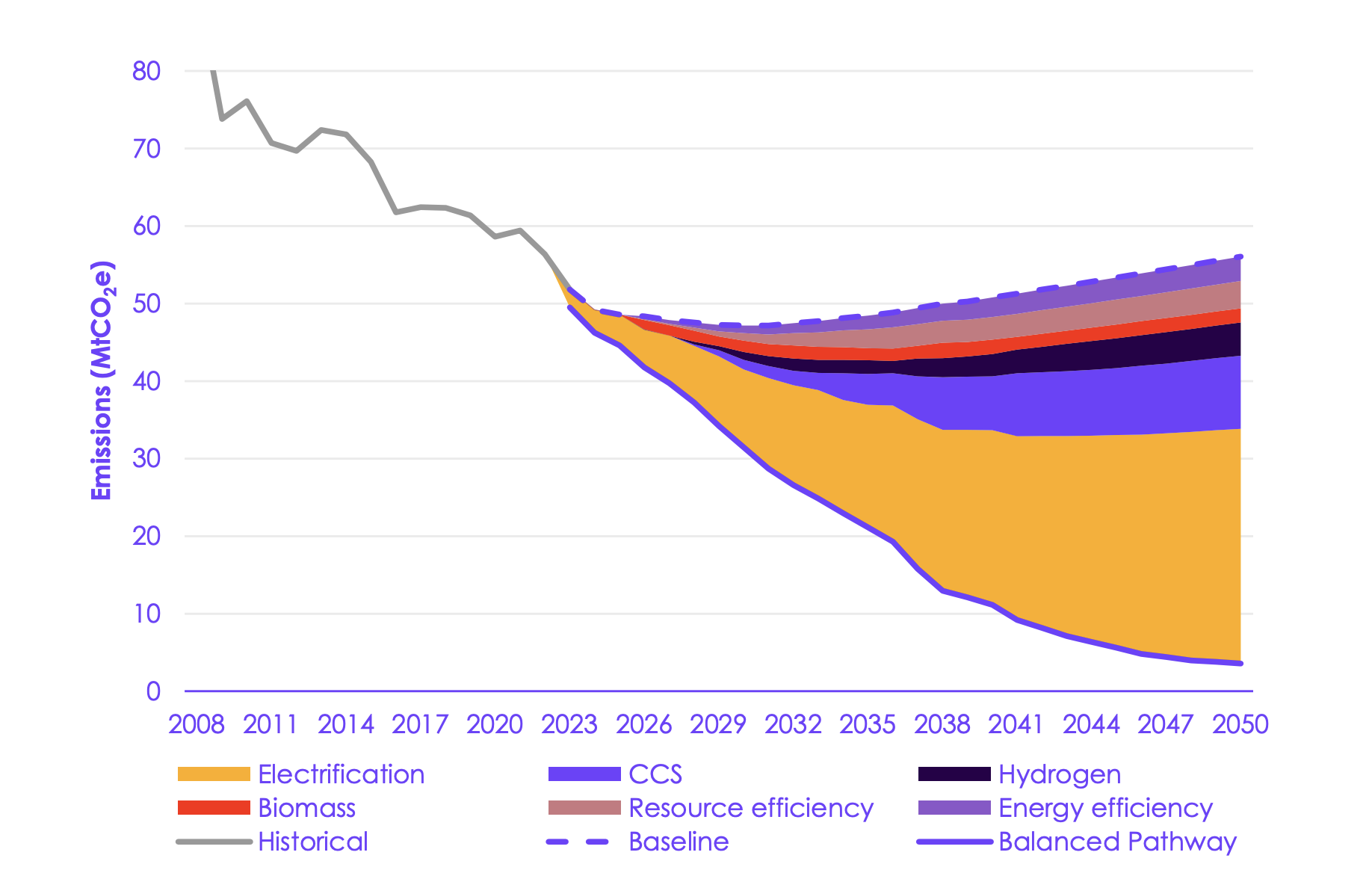

Industry

By 2040, the CCC’s balanced pathway sees emissions from industry falling by 78% from 52MtCO2e in 20223, with industrial output remaining largely unchanged.

It says that industry could almost completely decarbonise by 2050, with a large part of these reductions coming via electrification.

Emissions from industry have fallen by 63% since 1990, due predominantly to a steep decline in UK production of emissions-intensive materials.

A “structural shift” has seen lower-carbon, but higher-value industry outputs increase, such as pharmaceuticals and aerospace, allowing “gross value added” from the sector to grow by 26%, while energy consumption for each unit of output has fallen by 45% between 1998 and 2022.

At the same time, however, steel production has fallen from 18Mt in 1990 to 6Mt in 2023 and cement from 15Mt to 8Mt.

The closure of one of the UK’s last remaining blast furnaces, along with the expected closure of a second site, are expected to reduce emissions in the sector by at least another 8MtCO2e in 2024, the CCC says. It adds that the owners are planning to build electric arc furnaces at both sites, to maintain steel production with lower emissions.

Going forward, the largest share of emissions reduction for industry under the CCC’s balanced pathway is expected to come from electrification, representing 57% of savings in 2040.

The committee notes that there are already electrical alternatives to most types of fossil-fuelled heating used in industry, with many bringing “important advantages”, such as greater efficiency.

In cases where electrification is not possible, the CCC envisages fuel switching to hydrogen, as well as a limited amount of bioenergy and carbon capture and storage (BECCS) being used to compensate for industrial process emissions that cannot be avoided.

CCS is expected to account for 17% of industrial emissions cuts 2040, helping to tackle those from industrial subsectors with a high level of process emissions or where switching away from fossil fuels is not practical. As such, it is only deployed in two industrial subsectors within the balanced pathway: chemicals, and cement and lime.

The CCC has assumed that the capture rate of CCS technologies will be 90% until 2040, and 95% beyond that.

Hydrogen is expected to represent 7% of emissions reductions in 2040. In particular, it would play a “meaningful role” in decarbonising chemicals, glass and other minerals, iron and steel, as well as non-road mobile machinery.

Bioenergy is expected to reduce emissions by 5% by 2040. While many processes could, in theory, run on bioenergy, the CCC notes that it should be prioritised for subsectors that use CCS, particularly cement.

Combining bioenergy and CCS is expected to deliver 0.8 MtCO2e of CO2 removals by 2050.

Resource efficiency and energy efficiency are expected to represent 7% and 6% of emissions reductions in 2040, respectively.

The CCC’s pathway between 2025 and 2050 increases sector costs compared to a baseline. But there are potential additional benefits, for example, electrification offers an opportunity for manufacturers to provide more demand management services to the national grid.

It also notes that there is a potential competitive advantage for UK industry in decarbonising early, with low-carbon production expected to buck the wider trend of high-carbon goods demand falling.

To support the decarbonisation of industry, the CCC recommends that the government make electricity cheaper relative to gas, speed up the grid connection process, maintain support for CCS and hydrogen, plus strengthen the UK Emissions Trading Scheme, amongst other measures.

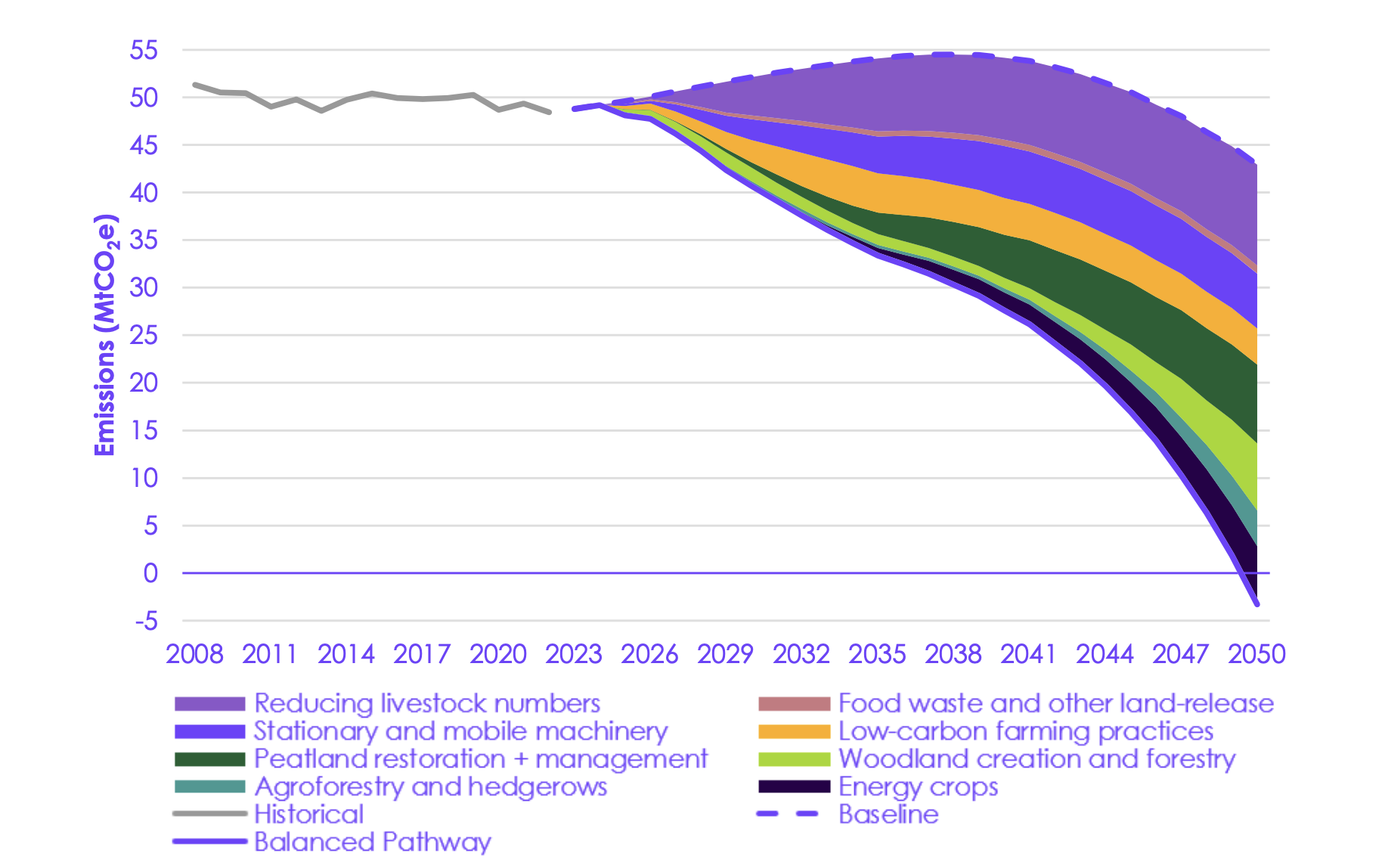

Agriculture and land use

Agriculture accounted for 11% of emissions in 2022 (47.7MtCO2e), while net emissions from land use, land-use change and forests were 0.8MtCO2e.

The CCC expects agricultural emissions to fall by 39% by 2040. Agricultural emissions will make up 27% of the UK’s emissions by 2040, making it the second-highest emitting sector at the time.

By 2050, the CCC’s pathway shows agricultural emissions falling to 26.4MtCO2e.

Emissions in the sector start lower in the seventh carbon budget’s modelling than in the previous iteration and fall further by around 10Mt. This is due to several factors, including changes to the inventory and emerging trends within meat consumption.

Speaking to Carbon Brief, the CCC’s director of analysis Dr James Richardson says:

“There is a trend in which red meat is losing ground within meat overall. And so we’ve reflected that trend in our assumptions that for any given amount of meat, less red meat within that reduces emissions. So that’s helping to bring down those agriculture numbers.”

Reducing livestock numbers is expected to reduce 32% of sectoral emissions by 2040 and release 68% of agricultural land by 2040. The government should support this shift, including helping to reduce average meat consumption by 25% by 2040 and 35% by 2050 compared to 2019 levels, according to the CCC.

Soils and livestock measures are expected to reduce emissions by 14% in 2040 and decarbonising machinery by 21%, as shown in the chart below. Other land-release measures are expected to reduce emissions by 2% and release 32% of land out of agriculture in 2040.

Land-use emissions are now 10MtCO2e lower than 1990 levels and are expected to become a small carbon sink of 1.9MtCO2e in 2040.

The CCC pathway sees peatland restoration and management reducing emissions by 17% in 2040. Woodland creation and management also reduce emissions by 4%, rising to 15% by 2050.

This follows the UK missing its tree-planting targets, failing to plant an area of forest nearly equivalent to the size of Birmingham, according to Carbon Brief analysis published last year.

Energy crops account for 7% of emissions reductions, with 0.7m hectares or almost 3% of UK land area allocated to three perennial crops – miscanthus, short-rotation coppice and short-rotation forestry by 2050. Agroforestry and hedgerows account for a 2% emissions reduction in 2040.

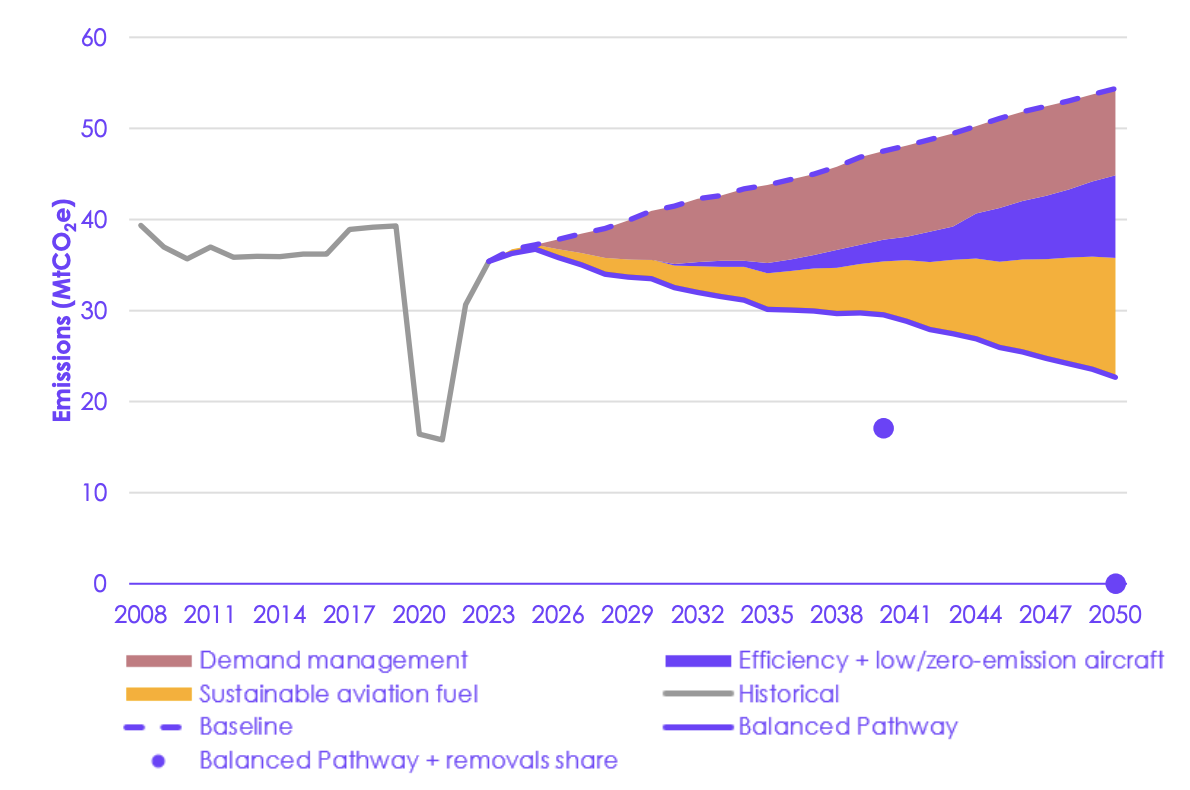

Aviation

Aviation emissions drop by 17% to 29.5MtCO2e in 2040 in the CCC’s balanced pathway. By which point, aviation would have risen from sixth position to be the highest-emitting sector, due to its slow pace of decarbonisation.

As aviation has “no credible way to completely decarbonise”, roughly 60% of the engineered CO2 removals by 2050 may need to balance out its emissions, according to the CCC. (These removals primarily come from bioenergy with carbon capture and storage.)

A core message within the CCC’s report is that the aviation sector should “pay for [its] share” of removals, as well as the broader costs of decarbonising and addressing the non-CO2 effects of flights on global warming. These costs would be “reflected in the price of flying”.

This, in turn, would help to discourage growth in the sector, which would also help to curb emissions, the CCC says. Overall, limiting the number of flights accounts for more than half of the emissions savings out to 2040.

However, this is compared to a baseline scenario in which per-capita distance flown grows 53% above 2025 levels by 2040. In the CCC’s pathway, demand remains fairly steady for the next decade, then increases 16% from 2025 levels by 2040

The advice comes in the wake of the government recently supporting the expansion of Heathrow and, potentially, other airports.

The CCC’s latest pathway allows for greater growth in passenger numbers than previous advice – 402 million by 2050, rather than 365 million. It has also dropped a previous recommendation that there should be “no net increase” in airport capacity.

However, it stresses that government and industry “may need to take additional demand management measures”, if technologies do not expand sufficiently to reduce emissions.

“Sustainable” aviation fuels (SAFs) account for 33% of emissions cuts by 2040 in the CCC’s pathway. This involves SAFs rising from meeting 1% of total demand today to 17%.

(The government and industry have emphasised their focus on SAFs, but many experts have doubts about how much they can be relied on to curb emissions.)

A further 13% of emissions savings in the CCC’s pathway come from efficiency improvements and, to a much lesser extent, the use of hybrid and zero-emission aircraft. The overall breakdown of emissions reductions is laid out in the chart below.

However, the CCC says that, with SAFs and CO2 removal still in the early stages of development, there remains great uncertainty around how aviation will decarbonise.

This means the final breakdown between these technologies and demand reduction could be very different. Therefore, it stresses that “all must be pursued” to ensure the UK meets its goals.

Finally, the CCC advises that the government should commit to monitoring and tackling the non-CO2 warming effects of aviation, as well as working with other countries to “go further” than the UN International Civil Aviation Organization (ICAO) to curb emissions from international flights.

Other sectors

The CCC’s balanced pathway also covers sectors that contribute smaller shares of UK emissions.

The largest of these is fuel supply – primarily, oil and gas production, as well as hydrogen and bioenergy – which accounts for 7% of UK emissions.

Even smaller shares come from waste and shipping, as well as fluorinated gases (F-gases), which are used in refrigeration, air conditioning, heat pumps and medical inhalers.

Here, Carbon Brief rounds up some of the key points and recommendations for these sectors:

- Fossil-fuel supply emissions are expected to decline even without any new policies, as North Sea production dwindles and demand falls due to electrification. Oil and gas production would fall 68% by 2040 and 85% by 2050 under the balanced pathway.

- The CCC says the government should provide incentives to encourage the electrification of oil and gas platforms and CCS use in refineries. It suggests “proactive transition plans” to help oil and gas workers find new employment.

- “Low-regret” hydrogen infrastructure, such as networks and storage, should be “fast-tracked” so it is available from the 2030s, the committee says.

- Bioenergy has an “important, but limited role in enabling decarbonisation”, met by increasing domestic supply of energy crops and fewer imports from overseas.

- Shipping emissions drop by 62% by 2040 and – unlike aviation – the sector could almost completely decarbonise by 2050 through improved efficiencies and a switch to low-carbon fuels and electricity, according to the CCC.

- Waste is one of the few sectors that is expected to continue emitting in 2050, due to hard-to-abate processes in wastewater, landfill methane emissions and uncaptured CO2 from energy from waste.

- The CCC says the UK will need to introduce regulations to replace F-gases with less harmful alternatives. It says 2024 EU regulations provide a useful model for what needs to be achieved.

What does the CCC say about imported emissions?

The CCC notes that a significant share of the UK’s overall carbon footprint is associated with goods and services imported from overseas.

Specifically, it says that imported emissions – at 381MtCO2e in 2021 – are of a similar scale to those that take place within the UK’s borders, which were 423MtCO2e that year.

Contrary to widespread perception, however, the committee notes that these imported emissions have barely changed over the past four decades.

In other words, emissions cuts within the UK’s borders have not been wiped out by increasingly “offshored” emissions embedded in imports.

Moreover, the report shows that nearly a third of these imported emissions – some 29% – relate to trade with the EU, whereas only 12% come from China. Similarly, the largest sectors are food and forestry imports (21%), rather than manufactured goods.

Many commentators have tried to argue that the UK should set climate goals based on its overall emissions footprint, on a so-called consumption basis rather than a territorial one.

However, the CCC explains that emissions taking place overseas are not under the jurisdiction of the UK government. It adds that attempting to regulate emissions imported into the UK “could undermine the accountability of other countries for their territorial emissions…[given] ultimate responsibility for reducing emissions lies with the producer”.

In addition, it notes that statistics on consumption-based emissions are “inherently uncertain”, which would make them “problematic” as a basis for legally binding carbon targets.

Instead, the CCC proposes a non-legally binding “benchmark” on imported emissions, which would set out the government’s expectations for how emissions from imports should decline over time.

The post CCC: Reducing emissions 87% by 2040 would help ‘cut household costs by £1,400’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

CCC: Reducing emissions 87% by 2040 would help ‘cut household costs by £1,400’

Climate Change

Satellites Reveal New Climate Threat to Emperor Penguins

Ice loss in the Antarctic Ocean may be killing the sea birds during their molting season.

Each year for millennia, emperor penguins have molted on coastal sea ice that remained stable until late summer—a haven during a span of several weeks when it’s dangerous for the mostly aquatic birds to enter the ocean to feed because they are regrowing their waterproof feathers.

Climate Change

States Sue to Block Trump’s ‘Anti-Science’ Vaccine Policy

Climate change helps spread vaccine-preventable diseases. But the Trump administration’s reduced vaccine schedule “throws science out the window,” and makes Americans more vulnerable to infections, state attorneys general charge in a new lawsuit.

Scientists have long warned that a warming world is likely to hasten the spread of infectious diseases, making vaccination even more critical to safeguard public health.

Climate Change

Hurricane Helene Is Headed for Georgians’ Electric Bills

A new storm recovery charge could soon hit Georgia Power customers’ bills, as climate change drives more destructive weather across the state.

Hurricane Helene may be long over, but its costs are poised to land on Georgians’ electricity bills. After the storm killed 37 people in Georgia and caused billions in damage in September 2024, Georgia Power is seeking permission from state regulators to pass recovery costs on to customers.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits