Since 2011, the UK has spent at least £12.63bn on 490 climate-related projects in developing countries from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe.

A new investigation by Carbon Brief reveals exactly how much of the UK’s foreign-aid budget is being used – and how – to help nations in the global south to cut emissions and better prepare for rising temperatures.

Freedom-of-information (FOI) requests submitted to the UK government have yielded new, detailed information about more than a decade of foreign-aid spending on climate change.

This comes at a time of intense scrutiny for the UK’s climate-finance spending, which it is legally bound to deliver under the terms of the Paris Agreement.

The government has slashed its aid budget and, as Carbon Brief’s analysis reveals, fallen behind on its pledge to spend £11.6bn on climate finance between 2021 and 2026.

Key findings from Carbon Brief’s analysis include:

- Annual climate finance spending has more than tripled from £392.5m in 2011/12 to nearly £1.40bn in 2022/23.

- Ethiopia has received the most single-country funding overall since 2011, a total of £377.5m. Kenya, Bangladesh and Uganda were also major recipients.

- Combined with government-reported public and private finance “mobilised” by UK funds, the UK’s total climate-finance contribution reached £26.49bn by 2023.

- Around 80% of climate funds go to projects targeting “developing countries” in general or regional funds, which are often run by large multilateral institutions.

In this analysis, Carbon Brief walks through the key findings and trends that emerge from this 12-year dataset.

- Carbon Brief’s FOI and project database

- How much climate finance has the UK spent?

- Where is UK climate finance being spent?

- What results has this climate finance produced?

- Methodology

Carbon Brief’s FOI and project database

Developed countries, such as the UK, have committed to providing “climate finance” to developing countries to help them cut emissions and prepare for a warming world.

In practice, this money is generally drawn from countries’ foreign-aid budgets. In the UK, this kind of aid is termed International Climate Finance (ICF).

The nation has been supporting ICF projects since 2011 and, throughout this period, it has funded everything from providing households in Nepal with solar power to ensuring flood-stricken communities in Malawi have enough to eat.

Climate finance is a highly politicised issue and developed countries are under intense pressure to deliver the money they have promised repeatedly to developing countries – and to spend it in ways that are “efficient” and achieve the greatest impact.

Specifically, they have a still-outstanding pledge to raise $100bn annually by 2020 and now must decide on a more ambitious goal by 2024. There are also questions around whether rich countries, including the UK, are paying their “fair share” based on their historic responsibility for climate change.

Over the past decade, the UK has been the world’s fifth-largest national provider of climate finance after – in descending order – Japan, Germany, France and the US, according to the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Carbon Brief carried out an earlier FOI request in 2017, obtaining information about all the climate finance projects the UK had funded since 2011, the year when ICF began. The findings were mapped and presented in full.

The UK government provides a catalogue of its foreign-aid projects on the Development Tracker website. However, while this service allows users to search for projects with an ICF component, it does not provide the breakdown or percentage of how much of each budget is solely allocated for ICF.

The government has also been submitting detailed information about how much funding from its foreign-aid projects is “climate-specific” to the UN. But these reports contain less information than Development Tracker and only go as far as 2020.

Given this, Carbon Brief has successfully repeated its earlier FOI, this time for the financial years 2017/18 to 2022/23. The government provided this data to Carbon Brief in May 2023.

The resulting data has now been combined with the original dataset, plus data extracted from Development Tracker project pages, to produce a new interactive table detailing every project that includes ICF spending between the financial years 2011/12 and 2022/23 – and the amount of funding that is climate-specific for each one. This can be viewed below.

The total includes £12.63bn of climate finance spent across 490 projects over this 11-year period.

Many ICF projects overseen by the Foreign, Commonwealth and Development Office (FCDO) and its predecessor the Department for International Development (DFID) are only partly related to climate change, meaning they may also cover other issues, such as education and healthcare. For these projects, only the climate-relevant proportion of spending – as determined by the FCDO – is included in Carbon Brief’s database.

Virtually all of the money included in this table is straightforward ICF. However, in their FOI responses, government departments also provided some additional funds that are counted towards their climate-finance totals.

These include “R&I [research and innovation] funds” – namely the Newton Fund and the Global Challenges Research Fund – which support scientific research in developing countries. Between 2018 and 2023, £117.5m from these funds was used as climate finance. (These funds cover a range of projects but have been grouped together here under one project name.)

While these funds were not initially counted towards the UK’s climate-finance goals, budgetary pressure over the years has led to climate-related projects from these schemes being used to make up ICF totals. The reverse has also happened when climate-related R&I projects were in danger of losing funding.

Another notable outlier is funding for “COP costs”. The government counts £99m that it spent hosting the COP26 climate summit in Glasgow in 2021 towards its goals.

(A read-only Google Sheet with the full dataset can be viewed here. For more information about this data, see the Methodology section at the end of the article.)

How much climate finance has the UK spent?

The UK has more than tripled its annual climate-finance spending from £392.5m in 2011/12 to nearly £1.40bn in 2022/23.

In total, it has spent £12.63bn of development aid on ICF programmes across this period. This amounts to around 8% of total foreign-aid spending.

However, ICF funding has dropped over the past two years from a peak of £1.56bn in 2020/21, despite a 2019 government target to significantly scale up climate finance to £11.6bn over five years out to 2025/26. (For more on this dip in climate finance, see Carbon Brief’s separate analysis.)

Three government departments have been responsible for the UK’s climate-finance projects, although they have shifted titles and responsibilities several times over the past decade.

The majority of projects – 65% of the total funding across 417 projects – have been handled by DFID and, since September 2020, FCDO, which replaced it when the department was rolled into the Foreign and Commonwealth Office.

The second largest portion – 32% of total funding across 46 projects – has been overseen by the energy department, which has been known as the Department of Energy and Climate Change (DECC), the Department for Business, Energy and Industrial Strategy (BEIS) and, since February 2023, the Department for Energy Security and Net Zero (DESNZ).

The remaining 3% has been handled by the Department for Environment Food and Rural Affairs (Defra) across 27 projects. (Unlike the other departments, which released “provisional” data for 2022/23 to Carbon Brief, Defra declined to share data for this year.)

Where is UK climate finance being spent?

The map below shows where the UK has directed single-country funds since 2011 and the total spending in these nations across the 11-year period.

Countries in shades of blue have received climate finance from the UK and those in orange would be eligible to receive it, but have not. (Those in grey are not eligible to receive aid.)

Many factors contribute to which countries receive ICF funds from the UK, including vulnerability to climate change, regional expertise and diplomatic ties.

“It is aid money that is subject to the whim of the donor, who will naturally be funding what is aligned to its national interest – some would argue rightly so,” Faten Aggad, a climate diplomacy expert and adjunct professor at the University of Cape Town tells Carbon Brief.

Of the 37 nations and territories that have received single-country funds, 17 are members of the Commonwealth – a group primarily made up of former British Empire colonies. A further two recipients, St Helena and Montserrat, remain British overseas territories.

Eighteen of the recipients are “least developed countries” (LDCs) – a UN grouping of 46 predominantly African states that are entitled to preferential access to aid. Only three recipients are independent small-island territories – Dominica, Haiti and Fiji.

Ethiopia is, by far, the biggest recipient of single-country funds, with £377.5m in total.

Most of this money has been provided through two sizable programmes aimed at increasing the Ethiopian government’s resilience to humanitarian shocks and increasing food security.

Case study: Productive Safety Net Programme

Location: Ethiopia

ICF spend: £190.8m between 2015/16 and 2019/2020

A social safety net programme – one of the largest in Africa – launched by the Ethiopian government and a group of donors in 2005 to help food-insecure households. It involved handing out food and cash either in exchange for labour on public works projects or unconditionally, for those who cannot work. The UK classed part of its contribution as climate finance because the public works being built include climate-proofing local infrastructure and the rehabilitation of habitats such as shrubland, which it says will absorb carbon dioxide (CO2). Boosting people’s food security also helped to “build resilience to climate shocks”. Money has been provided both directly to the Ethiopian Ministry of Finance and Economic Cooperation and to the World Bank, which also supports the project.

Several major recipients are emerging economies, which often have high emissions and are relatively wealthy.

According to the UK’s Independent Commission for Aid Impact (ICAI), these funds are often provided as loans, with the aim of attracting private investment and potentially creating opportunities for UK firms.

India has seen a dramatic increase in single-country funding. Carbon Brief’s previous analysis in 2017 showed that the UK had spent a total of £5m of ICF there, but now, largely thanks to a new , the total has risen to £144.8m.

Clare Shakya, a climate finance expert at the International Institute for Environment and Development (IIED), tells Carbon Brief:

“The UK’s development finance has traditionally been focused on those countries that most need support from among Britain’s ex-colonies, such as Bangladesh, Uganda and Kenya, and those which hold a strategic interest for the UK, such as Ethiopia, India or Nepal. The current government has been expanding the countries that it partners with on development, largely on the basis of strategic interest.”

As the chart below shows, only £2.55bn has been handed out as direct, single-country funds. The remainder is spent either through regional funds or even more broadly on “developing countries” in general.

Case study: Supporting structural reform in the Indian power sector

Location: India

ICF spend: £13.1m between 2017/18 and 2022/23

This project aims to improve the reliability of electricity supply in India through power-sector reform. It worked alongside a decentralised renewables programme also funded by the UK. In line with the government’s approach to providing aid to India, this project aimed to assist through “world-class” expertise, “not through traditional grant support”. The consultancy KPMGwas hired to provide “technical assistance” to the Indian Ministry of Power and other agencies. Other organisations are also brought into the project. The Shell Foundation – a charitable initiative of the oil company – was hired to promote the employment of women in the energy sector. The Behavioural Insights Team, originally set up by the UK government and dubbed “the nudge unit”, was also employed to apply behavioural insights to the Indian power sector and “influence customer behaviour”.

This is because most ICF is channelled through multilateral development banks, large consultancies and other organisations that ultimately decide how the money will be spent, although often with oversight from the UK and other contributors. (See: Who is the UK paying to run these projects?)

What results has this climate finance produced?

Each year, the UK government publishes a report laying out the impact its climate finance has had and its progress towards a selection of key performance indicators (KPIs). This includes the additional finance that its ICF funds has “mobilised”.

“Mobilised” refers to money from private sources – such as banks and companies – or from external public sources – such as UN bodies, development banks and the governments of recipient countries – which has been spent on climate action due to initial investment using ICF aid money.

These figures are important, not least because the annual $100bn (£80bn) goal that developed countries have promised to meet includes “mobilising” such additional sources.

The chart below shows how, according to the government’s reporting on its KPIs, these climate-finance sources have grown between 2014 and 2023. Combined with ICF spending, they bring the UK’s cumulative total to £26.49bn by 2023. (The government notes that only 297 projects have reported this additional impact, so the real total could be larger.)

Case study: UK Caribbean Infrastructure Fund

Location: Caribbean

ICF spend: £69.5m between 2016/17 and 2022/23

As part of a “major re-engagement between the UK and the Caribbean” in 2015, this fund was launched to build “climate-resilient” infrastructure in eight Commonwealth Caribbean nations and Montserrat, a UK overseas territory. It was given a boost in 2018 to support reconstruction in Dominica and Antigua and Barbuda, after hurricanes Irma and Maria tore through the region.The fund is run largely by the Caribbean Development Bank (CDB), a multilateral institution based in Barbados, with small team of UK government staff to support its delivery.

Beyond additional financing, the government also has a range of additional KPIs. The most recent report on their progress includes cumulative data up to 2022/23.

The table below shows progress on these indicators between 2014/15 and 2022/23.

Among other things, the government states that its ICF spending has “supported” nearly 102 million people to deal with the impacts of climate change and “reduced or avoided” 87m tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (MtCO2e).

As of 2023, the UK has doubled its list of KPIs to include new metrics such as the number of social institutions with improved access to clean energy and area of deforestation avoided.

Methodology

This analysis is based on a full dataset of ongoing and closed ICF projects, between 2011/12 and 2022/23, that Carbon Brief has assembled using FOI data and data extracted from government web pages.

The government’s Development Tracker website provides information on all of the development aid projects that the UK has spent money on, divided up among the departments that administer them. It includes data on the total budget of each project, but it does not include the breakdown of how much money in each budget is specifically set aside to address climate change.

Similarly, while the UK’s submissions to the UN include data on “climate-specific” finance, it does not consistently include sufficient information to identify all of the projects and only go as far as 2020.

To obtain this data, Carbon Brief sent FOI requests on 17 March 2023 to the three government departments responsible for ICF projects – FCDO, Defra and DESNZ. These requests asked for project-level annual ICF spend for the period 2017/18 to 2022/23 and the project ID code for each project.

The data was provided by all three departments towards the end of May. FCDO and DESNZ provided figures for 2022/23, noting that they are “provisional”. Defra, which accounts for only around 3% of total ICF spend, declined to provide these figures as it said the department was “yet to finalise” them.

This was then combined with annual ICF data for the period 2011/12 to 2016/17, which Carbon Brief had obtained in 2017 with another FOI request. This was achieved using the project codes to match up projects that had continued across these two periods. Further information, such as project names, descriptions and start/end dates, was then added using data scraped from ICF-tagged Development Tracker pages in June 2023 – again using project codes to match up projects. Data was extracted by Carbon Brief’s Tom Prater using Import.io and Octoparse.

The dataset can be viewed in this read-only Google Sheet, which includes an annual breakdown of spending. There are a few points to consider when exploring this data:

- A handful of projects had changed names, changed project IDs or moved to different departments. Carbon Brief matched up these projects with the correct details as far as possible, checking on specific details with the relevant departments.

- There remain 16 projects where no Development Tracker pages could be identified and, therefore, some information is missing (four of these include work in Afghanistan, so might have been removed for security reasons). This does not include COP26 costs and R&I funds, which do not have Development Tracker pages.

- For 10 of those projects, amounting to £13.27m in funds, a project location could not be identified and this will have a small effect on the country analysis. “COP costs”, which amount to £99m, also do not have a location.

- Some lines show negative spending. This can occur for several reasons, including a case where an investment funded through ICF has brought in returns, or if ICF spend has been incorrectly recorded and corrected, following quality assurance.

- The total number of ICF projects is higher than the number recorded on the government’s Development Tracker website, due to the FOI responses including a more comprehensive list of projects.

There are also issues with a number of Development Tracker pages, with many showing incorrect details at the time of publication and some of the links to project pages breaking.

This would not impact the ICF totals quoted in the article, which are derived from FOI requests, but may result in discrepancies when comparing the data included in the interactive table with project pages. The government has confirmed to Carbon Brief that it is aware of these issues.

The post Analysis: How the UK has spent its foreign aid on climate change since 2011 appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: How the UK has spent its foreign aid on climate change since 2011

Climate Change

Trump’s EPA Claims Strong Enforcement. But the Data Tells a Different Story.

The EPA released its latest enforcement and compliance report and touted the agency’s crackdown on environmental crimes under the Trump administration, yet 75 percent of the criminal cases closed last fiscal year originated before the president took office.

For over a decade, Hino Motors Ltd. imported and sold more than 105,000 vehicles and engines with misleading or fabricated emissions data, until testing by the Environmental Protection Agency revealed the emissions-fraud scheme.

Trump’s EPA Claims Strong Enforcement. But the Data Tells a Different Story.

Climate Change

CCC: Net-zero will protect UK from fossil-fuel price shocks

The “cost” of cutting UK emissions to net-zero is less than the cost of a single fossil-fuel price shock, according to a new report from the Climate Change Committee (CCC).

Moreover, a net-zero economy would be almost completely protected from fossil-fuel price spikes in the future, says the government’s climate advisory body.

The report is being published amid surging oil and gas prices after the US and Israel attacked Iran, which has triggered chaos on international energy markets.

It builds on the CCC’s earlier advice on the seventh “carbon budget”, which found that it would cost the UK less than 0.2% of GDP per year to reach its net-zero target.

In the new report, the CCC sets out for the first time a full cost-benefit analysis of the UK’s net-zero target, including the cost of clean-energy investments, lower fossil-fuel bills, the health benefits of cleaner air and the avoided climate damages from cutting emissions.

It finds that the country’s legally binding target to reach “net-zero emissions” by 2050 will bring benefits worth an average of £110bn per year to the UK from 2025-2050, with a total “net present value” of £1,580bn.

The CCC states that its new report responds to requests from parliamentarians and government officials seeking to better understand its cost assumptions, amid the ongoing cost-of-living crisis in the UK.

The report also pushes back on “misinformation” about the cost of net-zero, with CCC chair Nigel Topping saying in a statement that it is “important that decision-makers and commentators are using accurate information to inform debates”.

Co-benefits outweigh costs

The CCC’s new report is the first to compare the overall cost of decarbonising with the wider benefits of avoiding dangerous climate change, as well as other “co-benefits”, such as cleaner air and healthier diets.

It sets the CCC’s previous estimate of the net cost of net-zero – some £4bn per year on average out to 2050 – against the value of avoided damages and other co-benefits.

These “co-benefits” are estimated to provide £2bn to £8bn per year in net benefit by the middle of the century, according to the report.

The CCC notes that this approach allowed it to “fully appraise the value of the net-zero transition”.

It concludes that the net benefits of reaching net-zero emissions by 2050 are an average of £110bn per year from 2025 to 2050.

These benefits to the UK amount to more than £1.5tn in total and start to outweigh costs as soon as 2029, says the CCC, as shown in the figure below.

In addition, the CCC says that every pound spent on net-zero will bring benefits worth 2.2-4.1 times as much.

This updated analysis includes the value of benefits from improved air quality being 20% higher in 2050 than previously suggested by the CCC.

However, the “most significant” benefit of the transition is the avoidance of climate damages, with an estimated value of £40-130bn in 2050. The report states:

“Climate change is here, now. Until the world reaches net-zero CO2 [carbon dioxide] emissions, with deep reductions in other greenhouse gases, global temperatures will continue to rise. That will inevitably lead to increasingly extreme weather, including in the UK.”

The CCC’s conclusion is in line with findings from the Office for Budget Responsibility (OBR) in 2025, which suggested that the economic damages of unmitigated climate change would be far more severe than the cost of reaching net-zero.

The CCC notes that its approach to the cost-benefit analysis of the net-zero target is in line with the Treasury’s “green book”, which is used to guide the valuation of policy choices across UK government.

It says that one of the key drivers of overall economic benefit is a more efficient energy system, with losses halved compared with today’s economy.

It says that the UK currently loses £60bn a year through energy waste. For example, it says nearly half of the energy in gas is lost during combustion to generate electricity.

In a net-zero energy system, such energy waste would be halved to £30bn per year, says the CCC, thanks to electrified solutions, such as electric vehicles (EVs) and heat pumps.

For example, it notes that EVs are around four times more efficient than a typical petrol car and so require roughly a quarter of the energy to travel a given distance.

Collectively, these efficiencies are expected to halve energy losses, saving the equivalent of around £1,000 per household, according to the CCC.

Net-zero protects against price spikes

The CCC tests its seventh carbon budget analysis against a range of “sensitivities” that reflect the uncertainties in modelling methodologies and assumptions for key technologies. This includes testing the impact of a fossil-fuel price spike between now and 2050.

In the original analysis, the committee had assumed that the cost of fossil fuels would remain largely flat after 2030.

However, the report notes that, in reality, fossil-fuel prices are “highly volatile”. It adds:

“Fossil-fuel prices are…driven by international commodity markets that can fluctuate sharply in response to geopolitical events, supply constraints, and global demand shifts. A system that relies heavily on fossil fuels is, therefore, exposed to significant price shocks and heightened risk to energy security.”

It draws on previous OBR modelling of the impact of a gas price spike. This suggested that future price spikes would cost the UK government between 2-3% of GDP in each year the spike occurs, assuming similar levels of support to households and businesses as was provided in 2022-23.

The CCC adapts this approach to test a gas-price spike during the seventh carbon budget period, which runs from 2038 to 2042.

It finds that, if a similar energy crisis occurred in 2040 and no further action had been taken to cut UK emissions, then average household energy bills would increase by 59%. In contrast, bills would only rise by 4%, if the UK was on the path to net-zero by 2050.

The committee says that when considering the impact on households, businesses and the government, a single fossil-fuel price shock of this nature would cost the country more than the total estimated cost of reaching.

The finding is particularly relevant in the context of rising oil and gas prices following conflict in the Middle East, which has prompted some politicians and commentators to call for the UK to slow down its efforts to cut emissions.

In his statement, Topping said that it was “more important than ever for the UK to move away from being reliant on volatile foreign fossil fuels, to clean, domestic, less wasteful energy”.

Angharad Hopkinson, political campaigner for Greenpeace UK, welcomed this finding, saying in a statement:

“Each time this happens it gets harder and harder to swallow the cost. The best thing the UK can do for the climate is also the best thing for the cost of living crisis – get off the uncontrollable oil and gas rollercoaster that drags us into wars we didn’t want but still have to pay for. Inaction on climate is unaffordable.”

Benefits remain even if key technologies are more expensive

In addition to testing the impact of more volatile fossil-fuel prices, the CCC also tests the implications if key low-carbon technologies are cheaper – or more expensive – than thought.

It concludes that the upfront investments in net-zero yield significant overall benefits under all of the “sensitivities” it tested. As such, it offers a rebuttal to the common narrative that net-zero will cost the UK trillions of pounds.

The net cost of net-zero comes out at between 0% and 0.5% of GDP between 2025 and 2050, says the CCC, under the various sensitivities it tested.

“This sensitivity analysis shows that an electrified energy system is both a more efficient and a more secure energy system,” adds the CCC.

Finally, the report takes into account the costs of the alternative to net-zero. It looks at what would need to be spent in an economy where net-zero was not pursued any further.

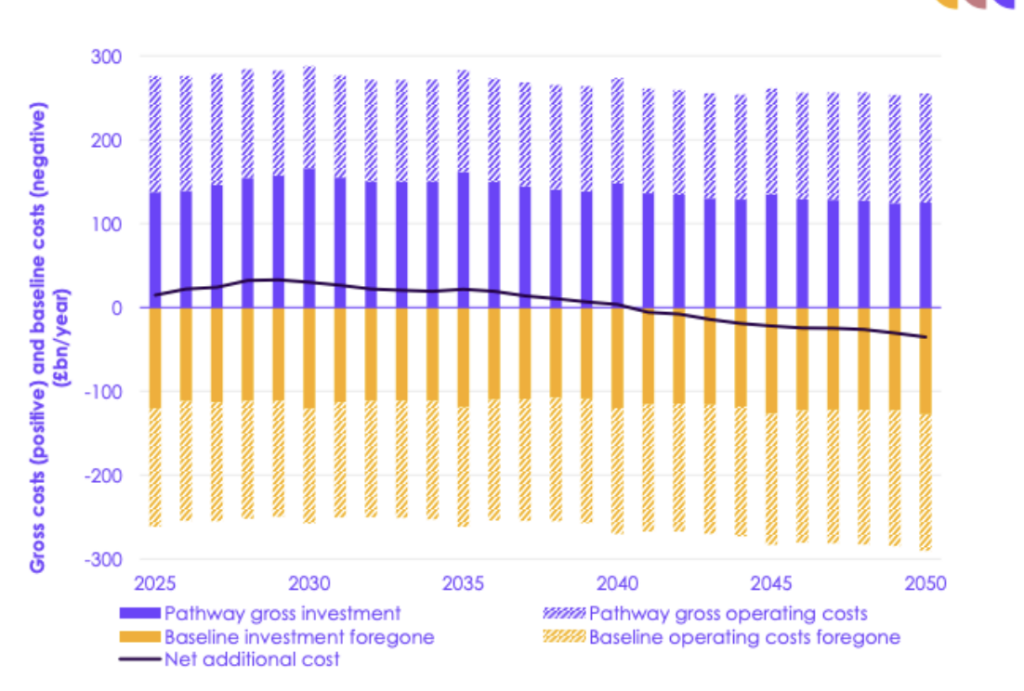

The CCC says that the gross system cost of the balanced pathway falls below the baseline cost from 2041, which is consistent with its previous seventh carbon budget advice.

As shown in the chart below, costs fall under a net-zero pathway between 2025 to 2050, whereas they rise in the baseline of no further action.

Moreover, the total costs of the alternatives are broadly similar, with the relatively small difference shown by the solid line.

The decline in energy system costs shown in the figure above is broadly driven by more efficient low-carbon technologies, says the CCC, helping costs to fall from 12% of GDP today to 7% by the middle of the century.

The CCC’s new analysis comes ahead of the UK parliament voting on and legislating for the seventh carbon budget, which it must do before 30 June 2026.

The post CCC: Net-zero will protect UK from fossil-fuel price shocks appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Following Months of Drought, Floods in Kenya Kill More Than 40 People

Climate change and urban development are exacerbating floods in the region, experts say.

After months of intense drought conditions, Kenya was inundated by rain late last week, triggering severe flooding that killed more than 40 people. In the country’s capital city, Nairobi, a month’s worth of rain fell in 24 hours.

Following Months of Drought, Floods in Kenya Kill More Than 40 People

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits