Scientists have long known that fires release substantial amounts of greenhouse gases and pollutants into the atmosphere.

However, estimating the total climate impact of fires is challenging.

Now, new satellite data has shed fresh light on the complex interplay between the climate and fires in different landscapes around the world.

It suggests that global emissions from fires are much higher than previously assumed.

In this article, we unpack the latest update to the Global Fire Emissions Database (GFED) – a resource that combines satellite information on fire activity and vegetation to estimate how fires impact the land and atmosphere.

The latest update to the database – explored in new research published in journal Scientific Data – includes data up to and including the year 2024.

It reveals that, once the data from smaller fires is included, fire emissions sit at roughly 3.4bn tonnes of carbon (GtC) annually – significantly higher than previous estimates.

It also shows that carbon emissions from fires have remained stable over the past two to three decades, as rising emissions from forest fires have been offset by a decline in grassland fire emissions.

The database update also illustrates how the amount of area burned around the world each year is falling as expanding agriculture has created a fragmented landscape and new restrictions on crop residue burning have come into force.

Landscape fires

Fire events vary widely in cause, size and intensity. They take place across the globe in many types of landscapes – deserts and ice sheets are the only biomes that are immune to fire.

When vegetation burns, it releases greenhouse gas emissions, which contribute to global warming. It also releases pollutants that cause local air pollution and, on a global scale, have a cooling effect on the climate.

Forest fires often generate considerable media attention, especially when they threaten places where people live.

However, the forest fires that make the news represent just a small fraction of all fires globally.

More than 95% of the world’s burned area occurs in landscapes with few trees, such as savannahs and grasslands.

Fires have helped maintain tropical savannah ecosystems for millions of years. Savannahs have the perfect conditions for fire: a wet season which allows grasses and other “fuels” to grow, followed by an extended dry season where these fuels become flammable.

Historically, these fires were ignited by lightning. Today, they are mostly caused – intentionally or accidentally – by humans.

And yet, despite their prevalence, these fires receive relatively little media attention. This is not surprising, as they have been part of the landscape for so long and rarely threaten humans, except for their impact on air quality.

Fires also occur in croplands. For example, farmers may use fire to clear agricultural residues after harvest, or during deforestation to clear land for cultivation.

The term “landscape fires” is increasingly used to describe all fires that burn on land – both planned and unplanned.

(The term “wildfire”, on the other hand, covers a subset of landscape fires which are unplanned and typically burn in underdeveloped and underinhabited land.)

Calculating the carbon emissions of landscape fires is important to better understand their impact on local air quality and the global climate.

New data

In principle, calculating carbon emissions from fires is straightforward. The amount of vegetation consumed by fire – or “fuel consumption” – in one representative “unit” of burned area has to be multiplied by the total area burned.

Fuel consumption can be determined through field measurements and satellite analysis.

For example, the burned area of a relatively small fire can be measured by walking around the perimeter with a GPS device. Fuel consumption, meanwhile, can be derived by measuring the difference in amount of vegetation before and after a fire, something that is usually only feasible with planned fires.

In practice, however, fires are unpredictable and highly variable, making accurate measurement difficult.

To track where and when fires occur, researchers rely on satellite observations.

For two decades, NASA’s MODIS satellite sensors have provided a continuous, global record of fire activity. To avoid too many false alarms, the algorithms these satellites use are built in a way so fires are flagged only when they burn an entire 500-metre grid cell.

However, this approach misses many smaller fires – resulting in conservative estimates of total burned area.

The latest update to the GFED includes, for the first time, finer-resolution satellite data, including from the European Space Agency’s “sentinel missions”.

This data shows that fires too small to be picked up by a satellite with a 500-metre spatial resolution are extremely common. So common, in fact, that they nearly double previous estimates of global burned area.

The data shows that, on average, 800 hectares of land – an area roughly the size of Australia – has burned annually over the past two decades.

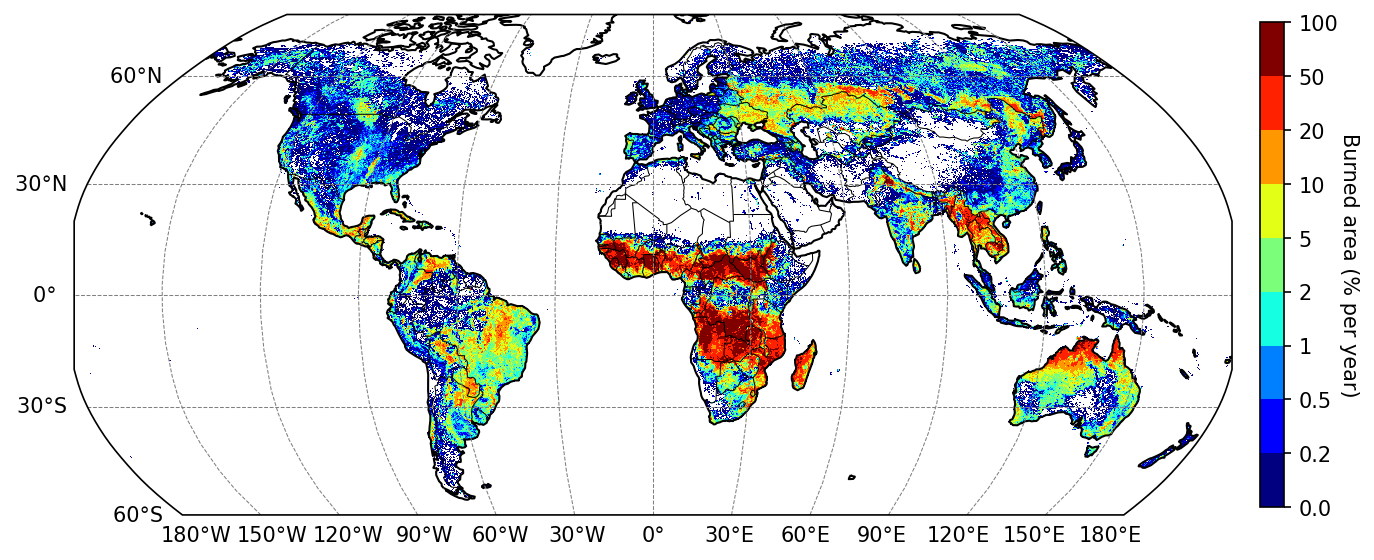

The map below shows the frequency of fires around the world. Regions shaded in dark red burn, on average, 50-100% each year. In other words, fires occur annually or biannually. Regions in dark blue, on the other hand, are those where fires occur, but are very infrequent. Most regions fall in between these extremes.

The map shows that the areas most prone to fire are largely found in the world’s savannah and agricultural regions.

Falling burned area

Over recent decades, the total burned area globally each year has been declining.

This is largely due to land-use change in regions which used to have frequent fires.

For example, savannah is being converted to croplands in Africa. This transforms a frequently burning land-use type to one that does not burn – and creates a more fragmented landscape with new firebreaks which limit the spread of fire.

The decline in burned area is also due to the introduction of more stringent air quality regulations limiting crop residue burning in much of the world, including the European Union.

The amount of “fuel” – or biomass – in a unit area of land varies greatly. Arid grasslands are biomass-poor and, therefore, produce less carbon emissions when burned, whereas fuel consumption in tropical forests with peat soils is extremely high.

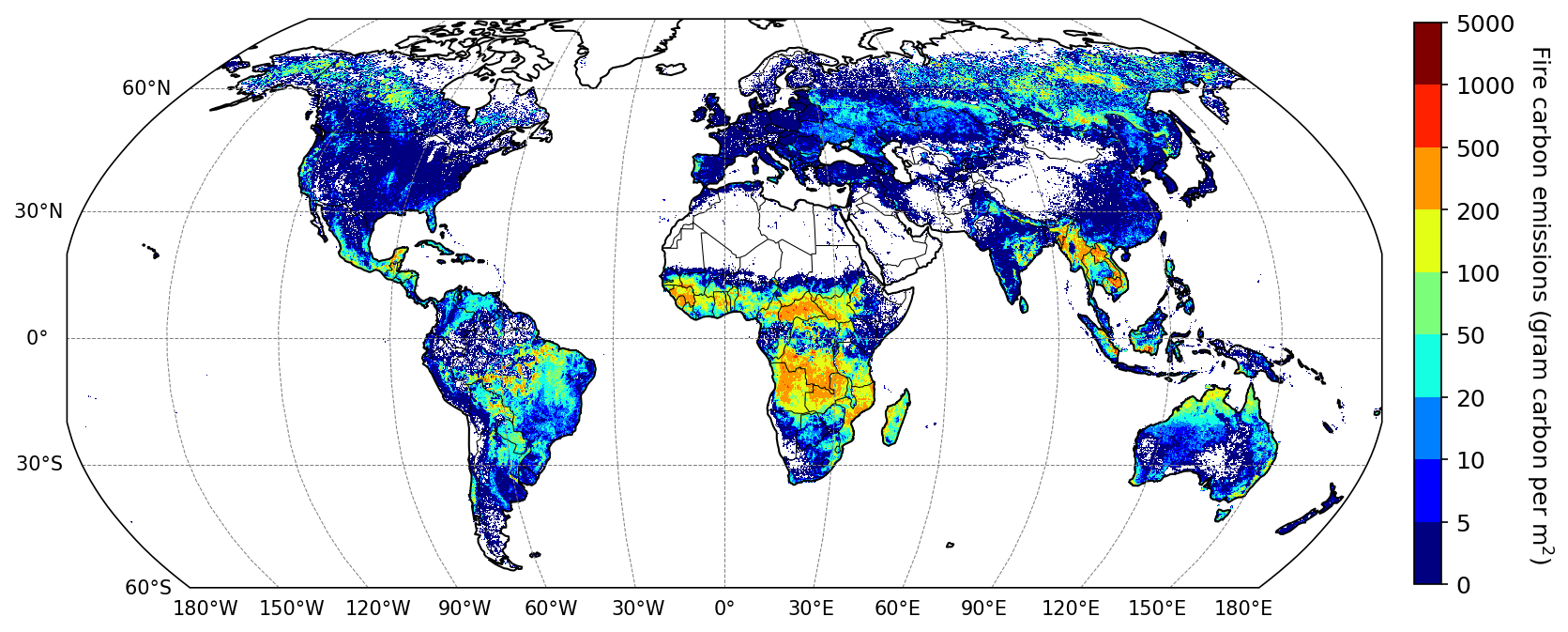

Maps of carbon emissions from fires closely resemble maps of burned area. However, they typically highlight biomass-rich areas, such as dense forests.

This is illustrated in the map below, which shows how fires in regions coloured dark red on the map produce, on average, 1,000-5,000 grams of carbon per square metre. In these places, much more carbon is lost during fires than gained through photosynthesis.

Meanwhile, much of the world’s savannah regions are coloured in yellow and orange on the map, indicating that fires here produce between 100-500 grams of carbon per square metre.

Rising forest fire carbon emissions

The boost in fire emissions captured by the latest version of the GFED is most pronounced in open landscapes, including savannahs, grasslands and shrublands.

Forest fire emissions, on the other hand, have barely changed in the updated version of the database. This is because most forest fires are relatively large and were already well captured by the coarse resolution satellite data used previously.

However, the trend in forest fire emissions is sloping upwards over the study period.

Overall, current estimates – which take into account the new data from smaller fires – suggest that, over 2002-22, global fire emissions averaged 3.4GtC per year.

This is roughly 65% higher than estimates set out in the previous update to the GFED, which was published in 2017.

For comparison, today’s fossil fuel emissions are around 10GtC per year.

Comparisons between fire and fossil fuel carbon emissions are somewhat flawed, as much of the carbon released by fires is eventually reabsorbed when vegetation regrows.

However, this is not the case for fires linked to deforestation or the burning of tropical peatlands, where regrowth is either much slower – or non-existent, if forests are converted to agriculture. These fires account for roughly 0.4GtC each year – just less than 12% of total fire emissions – and contribute directly to the long-term rise in atmospheric carbon dioxide (CO2).

The traditional view of forest fires as “carbon-neutral” is increasingly uncertain as the climate changes due to human activity. Longer fire seasons, drier vegetation and more lightning-induced ignitions are increasing fire frequency in many forested regions.

This is most apparent in the rapidly-warming boreal forests of the far-northern latitudes. The year 2023 saw the highest emissions ever recorded by satellites in boreal forests, breaking a record set just two years before.

Moreover, the fires in boreal forests are becoming more intense – meaning they burn hotter and consume a larger fraction of vegetation. This, in turn, jeopardises the recovery of forests.

In cold areas, fires also cause permafrost to break down faster. This happens because fires remove an organic soil layer that has an insulating effect which prevents permafrost thaw.

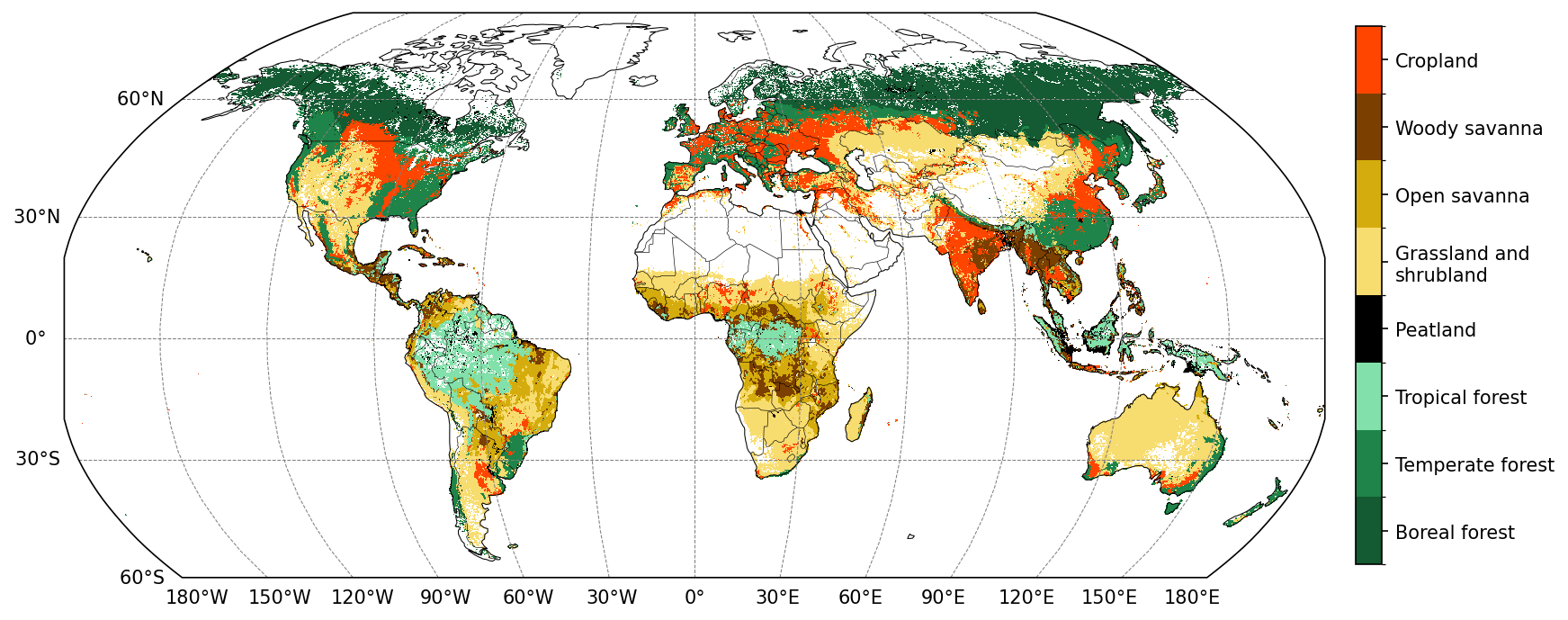

The map below shows the dominant fire type in different regions of the world, including boreal forest fires (dark green), cropland fires (red), open savannah (darker yellow) and woody savannah (brown).

Changing ‘pyrogeography’

Thanks to more precise satellite data we now know that fire emissions are higher than we thought previously, with the new version of GFED having 65% higher overall fire emissions than its predecessor.

However, all evidence suggests that emissions from fires have been stable over the past two to three decades. This is because an increase in forest fire emissions is being offset by a decline in grassland fire emissions.

The world’s changing “pyrogeography” is illustrated in the bar chart below, which breaks down annual fire emissions across different types of biome.

It shows how low-intensity grassland fires with modest fuel consumption – represented in yellow and brown – have declined over time, while high-intensity forest fires – illustrated in green colours – are becoming more prominent, albeit with substantial variability in emissions year-on-year.

The post Guest post: Why carbon emissions from fires are significantly higher than thought appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Guest post: Why carbon emissions from fires are significantly higher than thought

Climate Change

Petrochemical Expansion in Texas Will Fall Heavily on Communities of Color, Study Finds

Researchers in Houston analyzed the locations of 114 proposed industrial projects related to oil and gas in Texas, most of them involved in plastics production.

Researchers at Texas Southern University in Houston have analyzed demographic data around the locations of almost 100 industrial facilities proposed statewide and found that about 90 percent are located in counties with higher concentrations of people of color and families in poverty than statewide averages.

Petrochemical Expansion in Texas Will Fall Heavily on Communities of Color, Study Finds

Climate Change

For blighted Niger Delta communities, oil spill clean-ups are another broken promise

A thick, black liquid bubbles to the surface as Anthony Aalo pokes a stick into the muddy ground just outside Bodo, a fishing and farming community at the heart of Nigeria’s oil-drilling belt.

“You see? That’s oil,” the environmental activist said as he examined the sticky residue. “You can see the level of contamination, it’s still in the ground.”

Bodo, like other parts of Ogoniland in southern Nigeria’s Niger Delta region, still bears the scars of repeated oil spills spanning decades – despite being involved in two major clean-up operations over the last 10 years that promised to restore land and repair environmental damage.

Local fishermen say their catches have still not recovered from a massive 2008 oil spill that polluted the community’s water supplies and farmland, and decimated a nearby mangrove forest.

“Before you would have seen a lot of fish,” said Monday Saka, a 50-year-old fisherman, throwing a fishing net into the water from a traditional pirogue. “[Now], as you throw the net, nothing comes out.”

Big Oil’s environmental destruction

Bodo’s plight has become a symbol of the environmental destruction wrought by foreign oil companies in Nigeria, Africa’s largest oil producer, and the community continues to fight in the courts for adequate compensation to make up for lost livelihoods, health costs and environmental damage.

Shell agreed to pay the community compensation over the 2008 spill, and funded an environmental clean-up that ended last year.

Several sites in Bodo have also been earmarked for remediation as part of a $1-billion government-led clean-up for Ogoniland, billed by the United Nations as the world’s “most wide-ranging and long-term oil clean-up exercise” before work started six years ago.

UN experts accuse top oil firms of rights violations over Nigerian asset sales

The site in Bodo where Aalo, the activist, examined the oily ground was included in the first clean-up, but has yet to be reached by the ongoing Ogoniland-wide operation, known as the Hydrocarbon Pollution Remediation Project (HYPREP).

HYPREP, which is funded by a group of foreign oil companies and the Nigerian government, followed a damning 2011 assessment of oil-related damage by the UN Environment Programme (UNEP). The report said it could take 35 years to clean up Ogoniland.

But even as Nigerian President Bola Tinubu and some local leaders push for oil drilling to resume in Ogoniland for the first time in three decades, residents and environmental experts told Climate Home News and IrpiMedia that the government-led clean-up has fallen short of their expectations.

In line with the UNEP report, 65 sites were earmarked for the first phase of HYPREP’s soil and groundwater clean-up operations.

So far, 17 of them have been completed, the project’s leaders said in an update in June, detailing other achievements including the provision of drinking water distribution hubs, a power plant, a university centre of excellence for environmental restoration, and two new hospitals.

It also launched a coastal clean-up – not part of its original remit, which was over two-thirds done by October – as well as mangrove restoration that was 94% finished, according to a more recent statement. In addition, it notes 7,000 jobs have been created and 5,000 local people trained in a range of skills.

Nonetheless, some local activists and residents said HYPREP’s progress has been disappointing, with many blighted communities in Ogoniland not included in the initial list of sites to be remediated.

Others told this investigation that the project has strayed beyond its original remit into high-impact PR activities – such as the new hospitals and university centre, diverting focus from the laborious clean-up work. It takes about two years to clean each of the sites identified in the project’s first phase.

Funding shortfall

At the same time, there has been criticism over the disruption caused by frequent leadership changes.

A lack of money, however, is the biggest problem facing HYPREP today, said Evidence Ep-Aabari Enoch-Zorgbara, an oil and gas development expert and consultant who has previously worked for Shell and the Nigerian government. “Have we done enough? I will say no. Have we used the money well? I will say no. Have we done something? Yes. Are we at ground zero? No,” he said.

Colombia seeks to speed up a “just” fossil fuel phase-out with first global conference

The initial $1 billion in funding was meant to cover the first five years of work, but has not been topped up as planned, he said.

A 2025 UNEP assessment of the project said HYPREP’s long-term impacts depend on the replenishment of the trust fund underpinning the process, calling for the Nigerian government to work towards securing lasting funding for the ongoing implementation of HYPREP.

HYPREP and Nigeria’s Environment Ministry did not respond to repeated requests for comment on the project’s finances, but a senior HYPREP official told local media earlier this year that funding was not a problem – without addressing the issue of its future resources.

Doubts over efficacy of clean-up methods

Meanwhile, the labour-intensive work of cleaning contaminated water and farmland inches forward.

At a site near the settlement of K-Dere, contaminated water is pooled in basins, while polluted soil is excavated for treatment. Once the water and soil are cleaned and the pollutants fall below a certain threshold, it can be used again for traditional activities such as farming and fishing.

“We have a lot of work to do and we are trying to do it to the best of our abilities,” said team lead Israel Siglo, walking around the site in orange overalls and a protective helmet.

UNEP has rated such work positively, but independent monitors such as the NGO Stakeholder Development Network (SDN) have questioned some of the clean-up methods and their effectiveness.

Paul Samuel, from the SDN, said the group’s monitoring had found that treating soil with cleaning chemicals before transplanting it back does not tackle groundwater pollution nor make the land fit for agricultural use.

Without tackling contamination deeper in the ground, some experts fear progress made in the first phase could end up going to waste.

“We are about 20-30% of the way through the project, because groundwater remediation is still completely missing,” Enoch-Zorgbara said.

President: “Put this dark chapter behind us”

Last September, when announcing the push to resume oil production in Ogoniland for the first time since protests led by environmental activist Ken Saro-Wiwa in the 1990s, President Tinubu urged the Ogoni people to “put this dark chapter behind us and move forward as a united community”.

In a reminder of the persistent tensions between local people and government authorities 30 years since the execution of Saro-Wiwa by Nigeria’s then-military junta, security personnel with rifles slung over their shoulders keep guard at HYPREP’s headquarters in Port Harcourt.

In June, Tinubu’s government granted a posthumous pardon to Saro-Wiwa, whose killing sparked international outrage.

But for many Ogoni activists, such gestures are a government ploy to access the territory’s hydrocarbon reserves, as oil continues to leak from the aging pipelines criss-crossing the region.

“If there is anyone who needs a pardon, it is the federal government, not the Ogoni people who committed no offence,” said Celestine AkpoBari, a veteran environmental campaigner and coordinator of the Ogoni Solidarity Forum.

Not everyone in Ogoniland is opposed to new oil drilling, seeing it as a source of potential wealth for the region – as long as the lessons of the past are heeded.

Speaking to reporters from his palace in Port Harcourt, King Godwin Bebe Okpabi, the ruler of the Ogale community, said leaving the region’s oil riches in the ground “makes no sense” – even as the world strives to transition away from fossil fuels.

At the same time, King Okpabi is representing his community in a UK lawsuit against London-headquartered Shell and its former Nigerian subsidiary, which was taken over by Renaissance Africa Energy Company.

Having extracted oil in the area for decades, fossil fuel giants including Shell and Italy’s Eni are now accused by the local community of washing their hands of the responsibility for its aftermath by divesting from the region without adequately compensating for the pollution their activities caused.

Big banks’ lending to coal backers undermines Indonesia’s green plans

Shell has denied this, saying Renaissance will remain accountable for any clean-up and remediation work, while Eni has said that, at the time of the sale of its onshore operations, it had remediated “100% of the spills” on its joint venture assets.

TotalEnergies said it had fully met its financial obligations on remediation funding for environmental clean-up and site restoration purposes, including by contributing to HYPREP.

Oil firms blame spills on thieves

Energy companies have often blamed the frequent oil spills in Ogoniland on local oil thieves who drill holes in pipelines.

“This criminality is the cause of the majority of spills in the Bille and Ogale claims, and we maintain that Shell is not liable for the criminal acts of third parties or illegal refining,” a Shell spokesperson said.

But Enoch-Zorgbara and environmental activists say that the spills in Ogoniland were primarily caused by corrosion of aging oil infrastructure.

UNEP’s 2011 environmental assessment came in the wake of the devastating 2008 spill in Bodo, which took place when a decades-old pipeline, then operated by Shell, ruptured and leaked 3,900 barrels of oil for 72 consecutive days.

Black waves of crude swept through the fishing village and the surrounding areas, polluting rivers – a primary source of livelihood – contaminating fields, and destroying natural habitats.

After a group of Bodo residents took Shell to court, it acknowledged the environmental disaster had been caused by the erosion of the pipeline. Shell also agreed to restore the mangrove forest, which had shrunk by two-thirds as a result of the spill, and to pay £55 million ($72 million) in compensation to the community.

The 15,600 people behind the lawsuit received £2,200 each, with £20 million earmarked for community benefits, including a medical centre.

But for Saka, the fisherman in Bodo, the money does not make up for what the community has lost.

“Compared to what the oil destroyed in our river, the compensation is small – it cannot help us,” he said.

This article was published in partnership with IrpiMedia and Afrique XXI.

The post For blighted Niger Delta communities, oil spill clean-ups are another broken promise appeared first on Climate Home News.

For blighted Niger Delta communities, oil spill clean-ups are another broken promise

Climate Change

Europe must defend its deforestation law – for forests, business and its reputation

Stientje van Veldhoven is vice-president and regional director for Europe at the World Resources Institute. María Mendiluce is the CEO of the We Mean Business Coalition.

Europe aspires to be a competitive, innovative and investment-friendly economic bloc. Yet the foundations of such a market – political and financial stability and strong regulatory frameworks, as any economist will tell you – are exactly what the EU is undermining with its handling of the once pioneering EU Deforestation Regulation (EUDR).

The constant shifts in approach to this landmark law designed to counter global deforestation are bewildering, eroding Europe’s credibility as a stable, predictable market. The integrity of the EUDR suffered another blow last week in a vote by the European Parliament to further delay a year and simplify the regulation, which risks considerably changing the trajectory and the impact of the directive.

With no COP30 roadmap, hopes of saving forests hinge on voluntary initiatives

We call on the EU Commission to avert further horse-trading by withdrawing its earlier proposal to adjust the regulation.

Adopted in 2023 after years of negotiation, the EUDR is a well-communicated commitment to ensuring that goods – including coffee, cocoa, wood, beef and a few other commodities – placed on the EU market are not linked to deforestation or forest degradation. In effect, with the EUDR, the regulation draws a line between goods that deplete scarce natural capital and those that don’t.

Technical IT pause spirals

The stakes could not be higher. The EU is the second largest ‘deforester’ in the world, responsible for roughly 10% of global deforestation, despite representing only 6% of the world’s population. With that footprint comes the responsibility to limit its impact.

Since the directive passed, companies and producer-country governments have invested heavily in improving the traceability and transparency of their supply chains in preparation for the EU’s implementation. Yet the last two years have seen the regulation repeatedly weakened by one delay after another, each defended on ever more ambiguous grounds.

Comment: Investor action is crucial to maintaining progress on deforestation risk

To understand how we got here, it’s worth remembering that the European Commission’s initial proposal for a delay had a narrow and reasonable goal: resolving urgent, unforeseen technical issues with the EUDR’s IT system. There were also some smaller adjustments to reporting rules for micro and small companies directly selling their products on the EU market.

But what began as a technical pause to solve IT issues has spiralled into something far more unpredictable, political and messy. The new proposals approved by the EU Parliament now include another delay until the end of 2026 and a potential review of the impact of the regulation in April 2026, before it even comes into force. This would effectively open it back up for negotiation.

Rainforests suffering

What makes the EU’s capriciousness even more glaring are the near-simultaneous pleas at COP30 in Belém, made in front of many EU states, by Brazil’s President Lula and Environment Minister Marina Silva: to adopt a concrete, time-bound global forest roadmap to halt and reverse deforestation by 2030.

Their message was stark: the Amazon has suffered one of its most extreme droughts on record, accompanied by over 140,000 fires, mostly linked to land clearing for agriculture.

According to WRI’s Global Forest Watch, the world lost 6.7 million hectares of primary rainforest in 2024 alone – an area roughly the size of Ireland, or 18 football fields every minute. Emissions from these fires alone exceed India’s annual fossil fuel combustion.

Three problems of a weak EUDR

Being there, on the edge of the Amazon’s vast and breathtakingly biodiverse expanse, made the EU’s change of direction even more baffling to us. We see three major shortcomings in the EUDR proposals under consideration:

First, the proposal undermines market stability and business certainty. Major multinationals, including Nestlé, Mars, Ferrero, Danone, Olam Agri and Barry Callebaut have publicly warned against delaying the EUDR or inserting a review clause that would alter the contents of the law. They have invested heavily in traceability systems, supply-chain mapping and partnerships with producer countries, all under the assumption that the EUDR would be implemented as agreed. Reversing course now erodes trust, not just in the EUDR, but in the EU’s broader predictability as a market.

Second, delay allows European consumers to continue unknowingly driving deforestation. Most Europeans strongly reject the idea that their everyday purchases – from coffee and chocolate to steak or rubber tires – could be linked to forest destruction. Without the law in force, this environmental harm remains hidden in routine purchases, stripping consumers of their agency to ‘vote’ with their wallets.

Third, postponing the EUDR will slow global progress to halt and reverse deforestationat a moment when forests need urgent protection. Rainforests are far more than carbon reserves; they are the lungs and lifeblood of our planet, powering the global water cycle, sending rain across continents, and sustaining agriculture, rivers and food production for billions of people worldwide.

Commission should act now

The EUDR is not perfect, but the position of the EU Council and Parliament will only lead to more uncertainty. In previous cases, where the political compromise drifted far from the European Commission proposal, it has used its prerogative to withdraw an amended proposition.

The Commission now faces a clear choice: defend the EUDR, secure Europe’s market credibility, help protect forests that sustain life worldwide – or risk eroding all three.

The post Europe must defend its deforestation law – for forests, business and its reputation appeared first on Climate Home News.

Europe must defend its deforestation law – for forests, business and its reputation

-

Climate Change4 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases4 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits

-

Renewable Energy5 months ago

US Grid Strain, Possible Allete Sale