Feeding the 8.2 billion people who inhabit the planet depends on healthy soils.

Yet, soil health has been declining over the years, with more than one-third of the world’s agricultural land now described by scientists as “degraded”.

Furthermore, the world’s soils have lost 133bn tonnes of carbon since the advent of agriculture around 12,000 years ago, with crop production and cattle grazing responsible in equal part.

As a result, since the early 1980s, some farmers have been implementing a range of practices aimed at improving soil fertility, soil structure and soil health to address this degradation.

Soil health is increasingly on the international agenda, with commitments made by various countries within the Global Biodiversity Framework, plus a declaration at COP28.

Yet, there is still a lack of knowledge about the state of soils, especially in developing countries.

Below, Carbon Brief explains the state of soil health across the world’s farmlands, the factors that lead to soil degradation and the potential solutions to regenerate agricultural soils.

- What is soil health?

- Why are agricultural soils being degraded?

- Why is soil health important for food security and climate mitigation?

- How can CO2 removal techniques improve soil carbon?

- How can agricultural soil be regenerated?

- What international policies promote soil health?

What is soil health?

Agricultural soil is composed of four layers, known as soil horizons. These layers contain varying quantities of minerals, organic matter, living organisms, air and water.

The upper layers of soil are rich in organic matter and soil organisms. This is where crops and plants thrive and where their roots can be found.

Below the topsoil is the subsoil, which is more stable and accumulates minerals such as clay due to the action of rain, which washes down these materials from the topsoil to deeper layers of the soil.

The subsoil often contains the roots of larger trees. The deeper layers include the substrate and bedrock, which consist of sediments and rocks and contain no organic matter or biological activity.

Soil organic matter consists of the remains of plants, animals and microbes. It supports the soil’s ability to capture water and prompts the growth of soil microorganisms, such as bacteria and fungi, says Dr Helena Cotler Ávalos, an agronomic engineer at the Geospatial Information Science Research Center in Mexico.

Some of these organisms can help roots find nutrients, even over long distances, while others transform nutrients into forms that plants can use. Cotler Ávalos tells Carbon Brief:

“Life in the soil always starts by introducing organic matter.”

Soil is typically classified into three types – clay, silt and sand – based on the size and density of the soil’s constituent parts, as well as the mineral composition of the soil. Porous, loamy soils – a combination of clay, silt and sand – are considered the most fertile type of soil. The mineral composition also influences the properties of the soil, such as colour.

Healthy soils contain three macronutrients – nitrogen, phosphorus and potassium – alongside a range of micronutrients. They also contain phytochemicals, which have antioxidant and anti-inflammatory properties and are important for human health.

Below is a graphic showing the elements that constitute healthy soils, including non-mineral elements such as hydrogen, carbon and oxygen (shown in green), according to the Nature Education Knowledge Project.

The concept of “soil health” recognises the role of soil not only in the production of biomass or food, but also in global ecosystems and human health. The Intergovernmental Technical Panel on Soils – a group of experts that provides scientific and technical advice on soil issues to the Global Soil Partnership at the UN Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO) – defines it as the “ability of the soil to sustain the productivity, diversity and environmental services of terrestrial ecosystems”.

Soils can sequester carbon when plants convert CO2 into organic compounds through photosynthesis, or when organic matter, such as dead plants or microorganisms, accumulate in the soil. Soils also provide other ecosystem services, such as improving air and water quality and contributing to biodiversity conservation.

Why are agricultural soils being degraded?

The term “soil degradation” means a decline in soil health, which reduces its ability to provide ecosystem services.

Currently, about 35% of the world’s agricultural land – approximately 1.66bn hectares – is degraded, according to the FAO.

Introduced during the Industrial Revolution, modern-era industrialised agriculture has spread to dominate food production in the US, Europe, China, Russia and beyond.

Modern modes of industrial agriculture employ farming practices that can be harmful to the soil. Examples include monocropping, where a single crop is grown repeatedly, over-tilling, where the soil is ploughed excessively, and the use of heavy machinery, pesticides and synthetic fertilisers.

Agricultural soils are also degraded by overgrazing, deforestation, contamination and erosion.

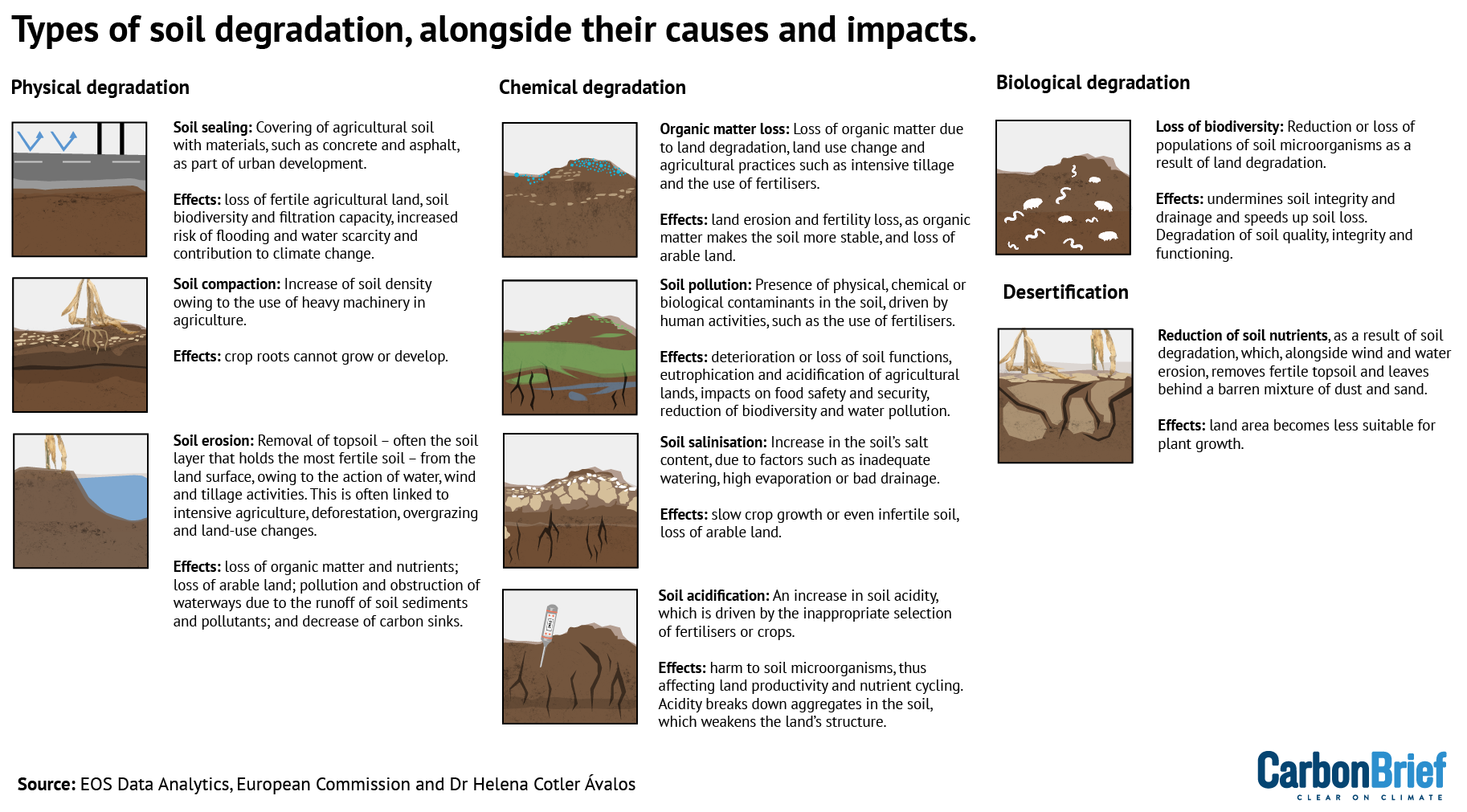

The diagram below depicts the different types of soil degradation: physical, chemical, biological and desertification.

Types of soil degradation, alongside their causes and impacts. Source: EOS Data Analytics, European Commission and Dr Helena Cotler Ávalos. Credit: Kerry Cleaver for Carbon Brief.

Industrial agriculture is responsible for 22% of global greenhouse gas emissions and also contributes to water pollution and biodiversity loss.

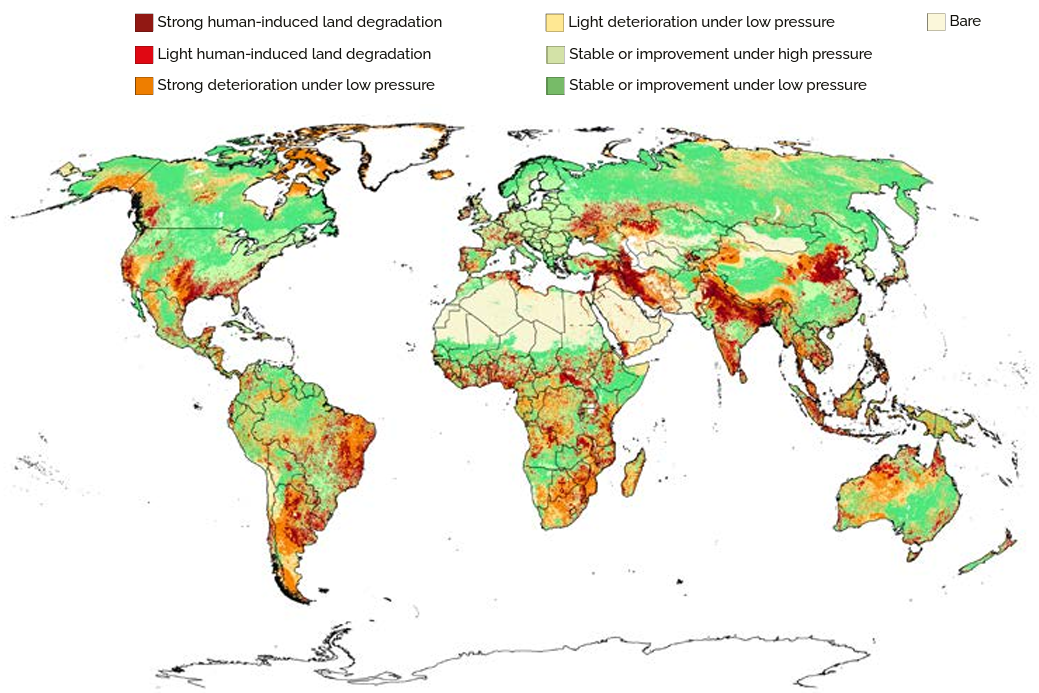

The map below, from the FAO, shows the state of land degradation around the world, from “strong” (dark red) to “stable or improv[ing]” (bright green).

It shows that the most degraded agricultural lands are in the southern US, eastern Brazil and Argentina, the Middle East, northern India and China.

Soil degradation became widespread following the Green Revolution in the 1940s, says Cotler Ávalos. During the Green Revolution, many countries replaced their traditional, diversified farming systems with monocultures. The Green Revolution also promoted the use of synthetic fertilisers and pesticides.

These changes led to a “dramatic increase” in yields, but also resulted in disrupting the interactions between microorganisms in the soil.

Cotler Ávalos tells Carbon Brief:

“It is the microorganisms that give life to soils. They require organic matter, which has been replaced by [synthetic] fertilisers.”

Today, there is a widespread lack of data on the condition of soils in developing countries.

For example, in sub-Saharan Africa, there are few studies measuring the rate and extent of soil degradation due to insufficient, reliable data. In Latin America, data on soil carbon dynamics are scarce.

Conversely, the EU released a report in 2024 about the state of its soils, spanning various indicators of degradation, including pollution, compaction and biodiversity change. The report estimates that 61% of agricultural soils in the EU are “degraded”, as measured by changes in organic carbon content, soil biodiversity and erosion levels.

The UK also has its own agricultural land classification maps, which classifies the condition of agricultural soils into categories ranging from “excellent” to “very poor”. This year, a report found that 40% of UK agricultural soils are degraded due to intensive agriculture.

Cotler Ávalos tells Carbon Brief:

“No country in the global south has data on how much of its soil is contaminated by agrochemicals, how much is compacted by the use of intensive machinery, how much has lost fertility due to the failure to incorporate organic matter.

“What is not studied, what is not known, seems to be unimportant. The problem of soil erosion is a social and political problem, not a technical one.”

Improved soil data, indicators and maps can help guide the sustainable management and regeneration of agricultural soils, experts tell Carbon Brief.

Why is soil health important for food security and climate mitigation?

As around 95% of the food the world consumes is produced, directly or indirectly, on soil, its health is crucial to global food security.

Food production needs to satisfy the demand of the global population, which is currently 8.2 billion and is expected to surpass 9 billion by 2037.

A 2023 review study pointed out that the total area of global arable land is estimated at 30m square kilometres, or 24% of the total land surface. Approximately half of that area is currently cultivated.

Studies have estimated that soil degradation has reduced food production by between 13% and 23%.

The 2023 review study also projected that land degradation could cut global food production by 12% in the next 25 years, increasing food prices by 30%.

Another recent study found that, between 2000 and 2016, healthy soils were associated with higher yields of rainfed corn in the US, even under drought conditions.

Research shows that soil health plays an important role in nutrition.

For example, a 2022 study found that a deficiency in plant nutrients in rice paddy soils in India is correlated with malnutrition. The country faces a growing amount of degraded land – currently spanning 29% of the total geographical area – and more than 15% of children are reported to suffer from deficiencies in vitamins A, B12 and D, along with folate and zinc, according to the study.

Soil health is also crucial for mitigating climate change.

Global agricultural lands store around 47bn tonnes of carbon, with trees contributing 75% of this total, according to a 2022 study.

Agricultural soils could sequester up to 4% of global greenhouse gas emissions annually and make a “significant contribution to reaching the Paris Agreement’s emissions reduction objectives”, according to a report from the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Some farming practices can reduce greenhouse gas emissions and improve soil carbon sequestration, such as improving cropland and grazing land management, restoring degraded lands and cultivating perennial crops or “cover crops” that help reduce erosion.

However, some scientists have warned that the amount of carbon that can be captured in global soils – and how long that carbon remains locked away – has been overestimated.

For example, an article published in Science in 2023 argued that one of the widely used models for simulating the flow of carbon and nitrogen in soils, known as DayCent, has “plenty of shortcomings”. It says:

“It doesn’t explicitly represent how soils actually work, with billions of microbes feasting on plant carbon and respiring much of it back to the atmosphere – while converting some of it to mineralised forms that can stick around for centuries.

“Instead, the model estimates soil carbon gains and losses based on parameters tuned using published experimental results.”

That, along with uncertainties associated with small-scale estimations, makes the model unable to accurately predict increases or decreases of soil carbon over time and, thus, a positive or negative impact on the climate, the outlet said.

How can CO2 removal techniques improve soil carbon?

Soils can also play a role in mitigating climate change through the use of CO2 removal techniques, such as biochar and enhanced rock weathering.

Biochar is a carbon-rich material derived from the burning of organic matter, such as wood or crop residues, in an oxygen-free environment – a process known as pyrolysis.

Biochar can be added to soils to enhance soil health and agricultural productivity.

Due to its porous nature, biochar holds nutrients in the soil, improving soil fertility, water retention, microbial activity and soil structure.

The long-term application of biochar can bring a range of benefits, such as improving yields, reducing methane emissions and increasing soil organic carbon, according to recent research that analysed 438 studies from global croplands.

However, the study added that many factors – including soil properties, climate and management practices – influence the magnitude of these effects.

Dr Dinesh Panday, a soil scientist at the agricultural research not-for-profit Rodale Institute and an expert in biochar, tells Carbon Brief that biochar typically is applied when soils have low carbon or organic matter content.

He adds that this technique is currently being used mostly in growing high-value crops, such as tomatoes, lettuce and peppers. For staple crops, including rice, wheat and maize, the use of biochar is only at a research stage, he adds.

Enhanced rock weathering is a process where silicate rocks are crushed and added to soils. The rocks then react with CO2 in the atmosphere and produce carbonate minerals, storing carbon from the atmosphere in the soil.

In the US, enhanced weathering could potentially sequester between 0.16-0.30bn tonnes of CO2 per year by 2050, according to a 2025 study.

Panday says that both biochar and enhanced weathering are mostly practised in developed countries at the moment and both have their own benefits and impacts. One of the disadvantages of biochar, he says, is its high cost, as producing it requires dedicated pyrolysis devices and the use of fossil gas. One negative effect of enhanced rock weathering is that it may alter nutrient cycling processes in the soil.

A 2023 comment piece by researchers from the University of Science and Technology of China raised some criticisms of biochar application, including the resulting emissions of methane and nitrous oxide, the enrichment of organic contaminants and heavy metals, and the dispersion of small particulate matter that can be harmful to human health.

Scientists still question how much carbon-removal techniques, such as enhanced rock weathering, can store in agricultural soils and for how long.

How can agricultural soil be regenerated?

Many types of farming practices can help conserve soil health and fertility.

These practices include minimising external inputs, such as fertilisers and pesticides, reducing tillage, rotating crops, using mixed cropping-livestock farming systems, applying manure or compost and planting perennial crops.

Low- or no-till practices involve stopping the large-scale turning over of soils. Instead, farmers using these systems plant seeds through direct drilling techniques, which helps maintain soil biodiversity. A 2021 review study found that in the south-eastern US, reducing tillage enhanced soil health by improving soil organic carbon, nitrogen and inorganic nutrients.

Mixed farming systems, which integrate the cultivation of crops with livestock, have also been found to be beneficial to soil health.

A 2022 study compared a conventional maize-soya bean rotation and a diverse four-year cropping system of maize, soya bean, oat and alfalfa in the mid-western US. It found that, compared to the conventional farm, the diversified system had a 62% increase in soil microbial biomass and a 157% increase in soil carbon.

One of the aims of soil regeneration is to make agricultural soil as much like a natural soil as possible, says Dr Jim Harris, professor of environmental technology at the Cranfield Environment Centre in the UK.

Harris, who is an expert in soil and ecological restoration, says that regenerating soils involves restoring the ecological processes that were once replaced by chemical inputs, while maintaining the soil’s ability to grow crops.

For example, he says, using regenerative agricultural approaches, such as rotational grazing, can help increase soil organic matter and fungi populations.

Which soil regeneration actions will be most successful will depend on the soil type, the natural climatic zone in which a farm is located, the rainfall and temperature regimes and which crops are being cultivated, he adds.

To measure the results of soil regeneration, farmers need to establish a baseline by determining the initial condition of the soil, then assess indicators of soil health. These indicators range from physical indicators, such as root depth, to biological indicators, such as earthworm abundance and microbial biomass.

In Sweden, researchers analysed these indicators in 11 farms that applied regenerative practices either recently or over the past 30 years. They found that the farms with no tillage, integration of livestock and organic matter permanent cover had higher levels of vegetation density and root abundance. Such practices had positive impacts on soil health, according to the researchers.

Switching from conventional to regenerative agriculture may take a farmer five to 10 years, Harris says. This is because finding the variants of a crop that are most resistant to, say, drought and pests could take a “long time”, but, ultimately, farms will have “more stable yields”, he says.

Harris tells Carbon Brief:

“Where governments can really help [is] in providing farmers with funds that allow them to make that transition over a longer period of time.”

Research has found that transitioning towards regenerative agriculture has economic benefits for farmers.

For example, farmers in the northern US who used regenerative agriculture for maize cropping had “29% lower grain production, but 78% higher profits over traditional corn production systems”, according to a 2018 study. (The profit from regenerative farms is due to low seed and fertiliser consumption and higher income generated by grains and other products produced in regenerative corn fields, compared to farms that only grow corn conventionally.)

A 2022 review study found that regenerative farming practices applied in 10 temperate countries over a 15-year period increased soil organic carbon without reducing yields during that time.

Meanwhile, a 2024 study analysing 20 crop systems in North America found that maize and soya bean yields increased as the crop system diversified and rotated. For example, maize income rose by $200 per hectare in sites where rotation included annual crops, such as wheat and barley. Under the same conditions, soya bean income increased by $128 per hectare, the study found.

The study pointed out that crop rotation – one of the characteristics of regenerative agriculture – contributes to higher yields, thanks to the variety of crops with different traits that allow them to cope with different stressors, such as drought or pests.

However, other research has questioned whether regenerative soil practices can have benefits for both climate mitigation and crop production.

A 2025 study modelled greenhouse gas emissions and yields in crops through to the end of the century. It found that grass cover crops with no tillage reduced 32.6bn tonnes of CO2-equivalent emissions by 2050, but reduced crop yields by 4.8bn tonnes. The lowest production losses were associated with “modest” mitigation benefits, with just 4.4bn tonnes of CO2e emissions reduced, the study added.

The authors explained that the mitigation potential of cover crops and no tillage was lower than previous studies that overlooked certain factors, such as soil nitrous oxide, future climate change and yields. Moreover, they warned, carbon removal using regenerative farming methods risks the release of emissions back into the atmosphere, if soil management returns to unsustainable practices.

Several of the world’s largest agricultural companies, including General Mills, Cargill, Unilever, Mars and Mondelez, have committed to regenerative agriculture goals. Nestlé, for example, has said that it is implementing regenerative agriculture practices in its supply chain that have had “promising initial results”. It adds that “farmers, in many cases, stand to see an increase in crop yields and profits”. As a result, the firm says it is committed to sourcing 50% of its ingredients from farms implementing regenerative agriculture by 2030.

However, Trellis, a sustainability-focused organisation, cautioned that “these results should be taken somewhat sceptical[ly]”, as there is no set definition on what regenerative agriculture is and measurement of the results is “lacking”.

In some places, the regeneration or recovery of agricultural soils is still practised alongside farmers’ traditional knowledge.

Ricardo Romero is an agronomist and the managing director of the cooperative Las Cañadas – Cloud Forest, lying 1300m above sea level in Mexico’s Veracruz mountains. There, cloud forests sit between tropical rainforest and pine forests, in what Romero considers “a very small ecosystem globally”, optimal for coffee plantations.

His cooperative is located on land previously used for industrial cattle farming. Today, the land is used for agroecological production of coffee, agroforestry and reforestation. The workers in the cooperative are mostly peasants who take on production and use techniques to improve soil fertility that they have learned by doing.

Romero says the soils in his cooperative have improved and crop yields have been maintained thanks to the compost they produce. He tells Carbon Brief:

“We are still in the learning stage. We sort of aspire to achieve what cultures such as the Chinese, Koreans and Japanese did. They returned all their waste to the fields and their agriculture lasted 4,000 years without chemical or organic fertilisers”.

What international policies promote soil health?

Soil health and soil regeneration feature in four of the targets under the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs).

(There are 169 targets under the SDGs that contain measurable indicators for assessing progress towards each of the 17 goals.)

For example, target 15.3 calls on countries to “restore degraded land and soil” and “strive to achieve a land-degradation neutral world”.

Soil health is increasingly being recognised in international negotiations under the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change (UNFCCC), UN Convention on Biological Diversity (UN CBD) and the UN Convention to Combat Desertification (UNCCD), says Katie McCoshan, senior partnerships and international engagement manager for the Food and Land Use Coalition (FOLU).

Each of these conventions has established its own work groups, declarations and frameworks around soil health in recent years.

Ideally, says McCoshan, action on soils should be integrated across the three different conventions, as well as in conversations around food and nutrition.

However, work across the three conventions remains siloed.

Currently, agriculture is formally addressed under the UNFCCC via the Sharm el-Sheikh joint work on implementation of climate action on agriculture and food security, a four-year work plan agreed at COP27 in 2022. This work group is meant to provide countries with technical support and facilitate collaboration and research.

The COP27 decision that created the Sharm el-Sheikh agriculture programme “recognised that soil and nutrient management practices and the optimal use of nutrients…lie at the core of climate-resilient, sustainable food production systems and can contribute to global food security”.

At COP28 in Dubai, the presidency announced the Emirates Declaration on Sustainable Agriculture, Resilient Food Systems and Climate Action. The 160 countries that signed the declaration committed to integrating agriculture and food systems into their nationally determined contributions, national adaptation plans and national biodiversity strategies and action plans (NBSAPs). The declaration also aims to enhance soil health, conserve and restore land.

Harris says the Emirates Declaration is a “great first step”, but adds that it will “take time to develop the precise on-the-ground mechanisms” to implement such policies in all countries, as “they are moving at different speeds”.

Within the UNFCCC process, soil has also featured in non-binding initiatives such as the 4 per 1000, adopted at COP21 in Paris. The initiative aims to increase the amount of carbon sequestered in the top 30-40cm of global agricultural soils by 0.4%, or four parts per thousand, per year.

The UNCCD COP16, which took place in 2024 in Saudi Arabia, delivered a decision to “encourage” countries to avoid, reduce and reverse soil degradation of agricultural lands and improve soil health.

Although COP16 did not deliver a legally binding framework to combat drought, it resulted in the creation of the Riyadh Global Drought Resilience Partnership, a global initiative integrated by countries, international organisations and other countries to allocate $12bn towards initiatives to restore degraded land and enhance resilience against drought.

The COP also resulted in the Riyadh Action Agenda, which aspires to conserve and restore 1.5bn hectares of degraded land globally by 2030.

Although soil health appears under both conventions, it is not included as formally in the UNFCCC as in the UNCCD – as in the latter there is a direct mandate for countries to address soil health and land restoration, McCoshan tells Carbon Brief.

Under the UNCCD, countries have to establish land degradation neutrality (LDN) targets by 2030. To date, more than 100 countries have set these targets.

Under the biodiversity convention, COP15 held in Montreal in 2022 delivered the Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework (GBF), a set of goals and targets aiming to “halt and reverse” biodiversity loss by 2030. Under the framework, targets 10 and 11 reference sustainable management of agriculture through agroecological practices, and the conservation and restoration of soil health, respectively.

A recent study suggests that restoring 50% of global degraded croplands could avoid the emission of more than 20bn tonnes of CO2 equivalent by 2050, which would be comparable to five times the annual emissions from the land-use sector. It would also bring biodiversity benefits and contribute to target 10 of the GBF and to UNCCD COP16 recommendations, the study added.

McCoshan tells Carbon Brief:

“[All] the pledges are important and they hold countries accountable, but that alone isn’t what we need. We’ve got to get the financing right and co-create solutions with farmers, Indigenous people, youth, businesses and civil society as well.”

The post Q&A: The role of soil health in food security and tackling climate change appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: The role of soil health in food security and tackling climate change

Climate Change

Climate at Davos: Energy security in the geopolitical driving seat

The annual World Economic Forum got underway on Tuesday in the Swiss ski resort of Davos, providing a snowy stage for government and business leaders to opine on international affairs. With attention focused on the latest crisis – a potential US-European trade war over Greenland – climate change has slid down the agenda.

Despite this, a number of panels are addressing issues like electric vehicles, energy security and climate science. Keep up with top takeaways from those discussions and other climate news from Davos in our bulletin, which we’ll update throughout the day.

From oil to electrons – energy security enters a new era

Energy crises spurred by geopolitical tensions are nothing new – remember the 1970s oil shock spurred by the embargo Arab producers slapped on countries that had supported Israel during the Yom Kippur War, leading to rocketing inflation and huge economic pain.

But, a Davos panel on energy security heard, the situation has since changed. Oil now accounts for less than 30% of the world’s energy supply, down from more than 50% in 1973. This shift, combined with a supply glut, means oil is taking more of a back seat, according to International Energy Agency boss Fatih Birol.

Instead, in an “age of electricity” driven by transport and technology, energy diplomacy is more focused on key elements of that supply chain, in the form of critical minerals, natural gas and the security buffer renewables can provide. That requires new thinking, Birol added.

“Energy and geopolitics were always interwoven but I have never ever seen that the energy security risks are so multiplied,” he said. “Energy security, in my view, should be elevated to the level of national security today.”

In this context, he noted how many countries are now seeking to generate their own energy as far as possible, including from nuclear and renewables, and when doing energy deals, they are considering not only costs but also whether they can rely on partners in the long-term.

In the case of Europe – which saw energy prices jump after sanctions on Russian gas imports in the wake of Moscow’s invasion of Ukraine – energy security rooted in homegrown supply is a top priority, European Commission President Ursula von der Leyen said in Davos on Tuesday.

Outlining the bloc’s “affordable energy action plan” in a keynote speech at the World Economic Forum, she emphasised that Europe is “massively investing in our energy security and independence” with interconnectors and grids based on domestically produced sources of power.

The EU, she said, is trying to promote nuclear and renewables as much as possible “to bring down prices and cut dependencies; to put an end to price volatility, manipulation and supply shocks,” calling for a faster transition to clean energy.

“Because homegrown, reliable, resilient and cheaper energy will drive our economic growth and deliver for Europeans and secure our independence,” she added.

Comment – Power play: Can a defensive Europe stick with decarbonisation in Davos?

AES boss calls for “more technical talk” on supply chains

Earlier, the energy security panel tackled the risks related to supply chains for clean energy and electrification, which are being partly fuelled by rising demand from data centres and electric vehicles.

The minerals and metals that are required for batteries, cables and other components are largely under the control of China, which has invested massively in extracting and processing those materials both at home and overseas. Efforts to boost energy security by breaking dependence on China will continue shaping diplomacy now and in the future, the experts noted.

Copper – a key raw material for the energy transition – is set for a 70% increase in demand over the next 25 years, said Mike Henry, CEO of mining giant BHP, with remaining deposits now harder to exploit. Prices are on an upward trend, and this offers opportunities for Latin America, a region rich in the metal, he added.

At ‘Davos of mining’, Saudi Arabia shapes new narrative on minerals

Andrés Gluski, CEO of AES – which describes itself as “the largest US-based global power company”, generating and selling all kinds of energy to companies – said there is a lack of discussion about supply chains compared with ideological positioning on energy sources.

Instead he called for “more technical talk” about boosting battery storage to smooth out electricity supply and using existing infrastructure “smarter”. While new nuclear technologies such as small modular reactors are promising, it will be at least a decade before they can be deployed effectively, he noted.

In the meantime, with electricity demand rising rapidly, the politicisation of the debate around renewables as an energy source “makes no sense whatsoever”, he added.

The post Climate at Davos: Energy security in the geopolitical driving seat appeared first on Climate Home News.

Climate at Davos: Energy security in the geopolitical driving seat

Climate Change

A Record Wildfire Season Inspires Wyoming to Prepare for an Increasingly Fiery Future

As the Cowboy State faces larger and costlier blazes, scientists warn that the flames could make many of its iconic landscapes unrecognizable within decades.

In six generations, Jake Christian’s family had never seen a fire like the one that blazed toward his ranch near Buffalo, Wyoming, late in the summer of 2024. Its flames towered a dozen feet in the air, consuming grassland at a terrifying speed and jumping a four-lane highway on its race northward.

A Record Wildfire Season Inspires Wyoming to Prepare for an Increasingly Fiery Future

Climate Change

Analysis: UK newspaper editorial opposition to climate action overtakes support for first time

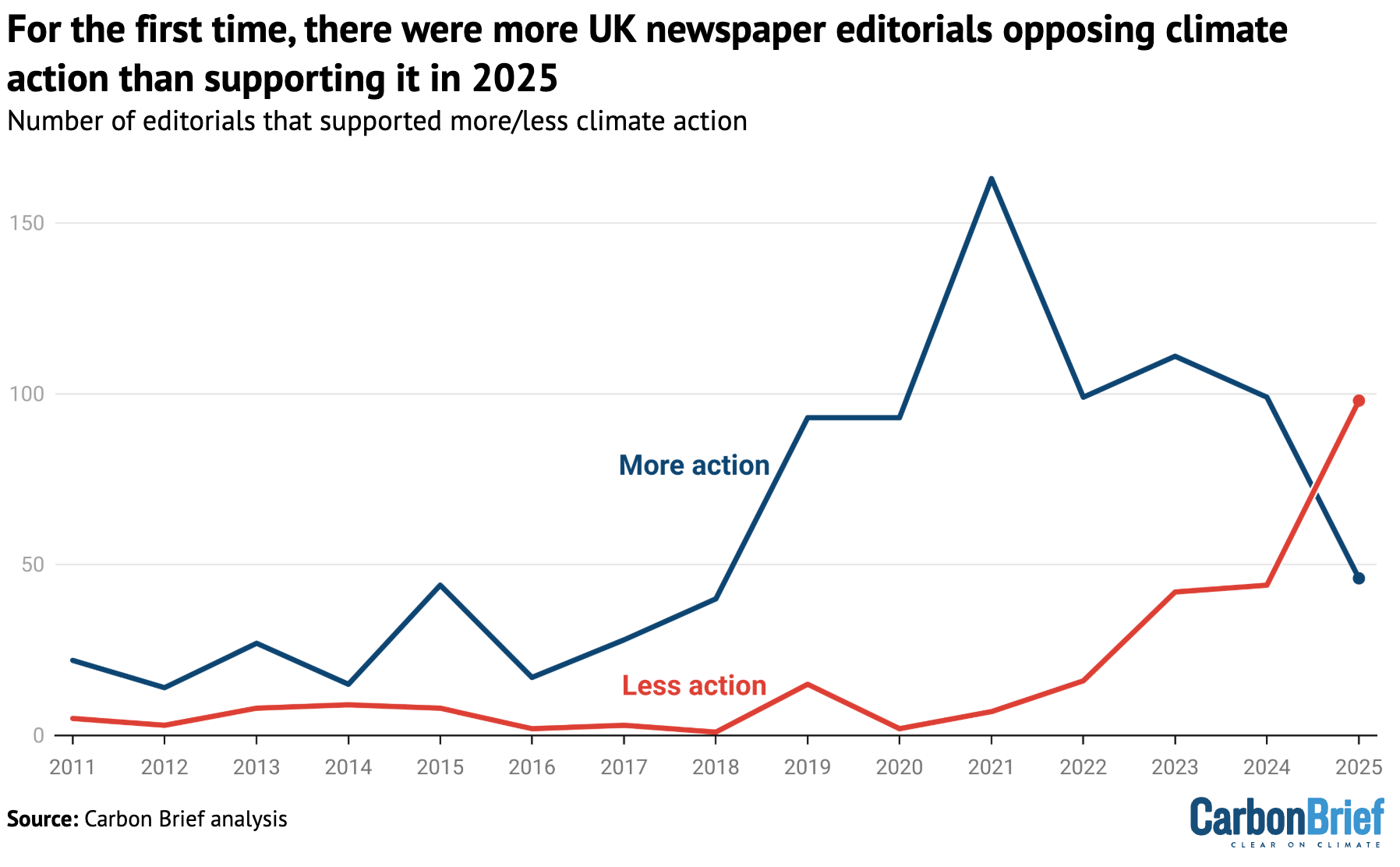

Nearly 100 UK newspaper editorials opposed climate action in 2025, a record figure that reveals the scale of the backlash against net-zero in the right-leaning press.

Carbon Brief has analysed editorials – articles considered the newspaper’s formal “voice” – since 2011 and this is the first year opposition to climate action has exceeded support.

Criticism of net-zero policies, including renewable-energy expansion, came entirely from right-leaning newspapers, particularly the Sun, the Daily Mail and the Daily Telegraph.

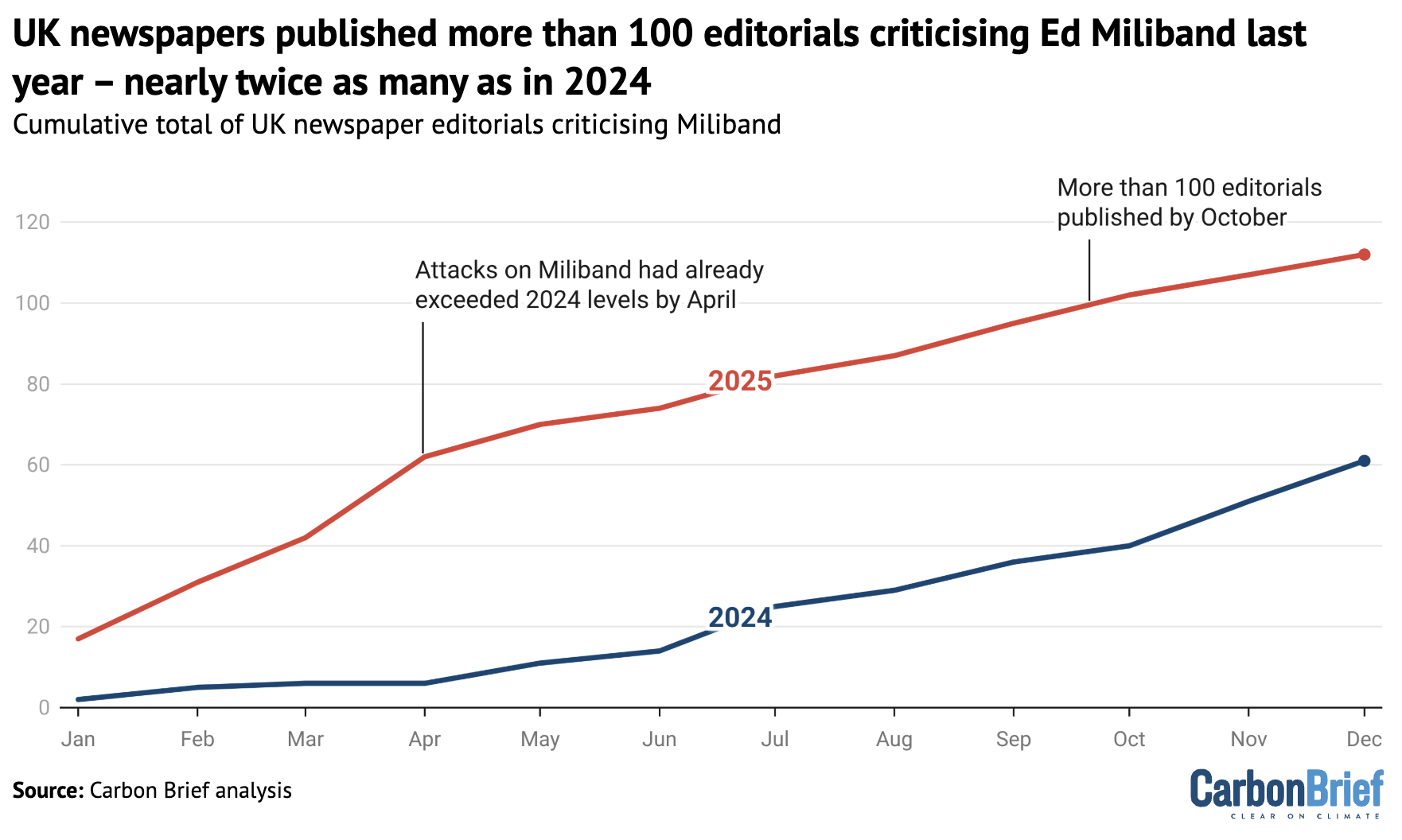

In addition, there were 112 editorials – more than two a week – that included attacks on Ed Miliband, continuing a highly personal campaign by some newspapers against the Labour energy secretary.

These editorials, nearly all of which were in right-leaning titles, typically characterised him as a “zealot”, driving through a “costly” net-zero “agenda”.

Taken together, the newspaper editorials mirror a significant shift on the UK political right in 2025, as the opposition Conservative party mimicked the hard-right populist Reform UK party by definitively rejecting the net-zero target that it had legislated for and the policies that it had previously championed.

Record climate opposition

Nearly 100 UK newspaper editorials voiced opposition to climate action in 2025 – more than double the number of editorials that backed climate action.

As the chart below shows, 2025 marked the fourth record-breaking year in a row for criticism of climate action in newspaper editorials.

This also marks the first time that editorials opposing climate action have overtaken those supporting it, during the 15 years that Carbon Brief has analysed.

This trend demonstrates the rapid shift away from a long-standing political consensus on climate change by those on the UK’s political right.

Over the past year, the Conservative party has rejected both the “net-zero by 2050” target that it legislated for in 2019 and the underpinning Climate Change Act that it had a major role in creating. Meanwhile, the Reform UK party has been rising in the polls, while pledging to “ditch net-zero”.

These views are reinforced and reflected in the pages of the UK’s right-leaning newspapers, which tend to support these parties and influence their politics.

All of the 98 editorials opposing climate action were in right-leaning titles, including the Sun, the Daily Mail, the Daily Telegraph, the Times and the Daily Express.

Conversely, nearly all of the 46 editorials pushing for more climate action were in the left-leaning and centrist publications the Guardian and the Financial Times. These newspapers have far lower circulations than some of the right-leaning titles.

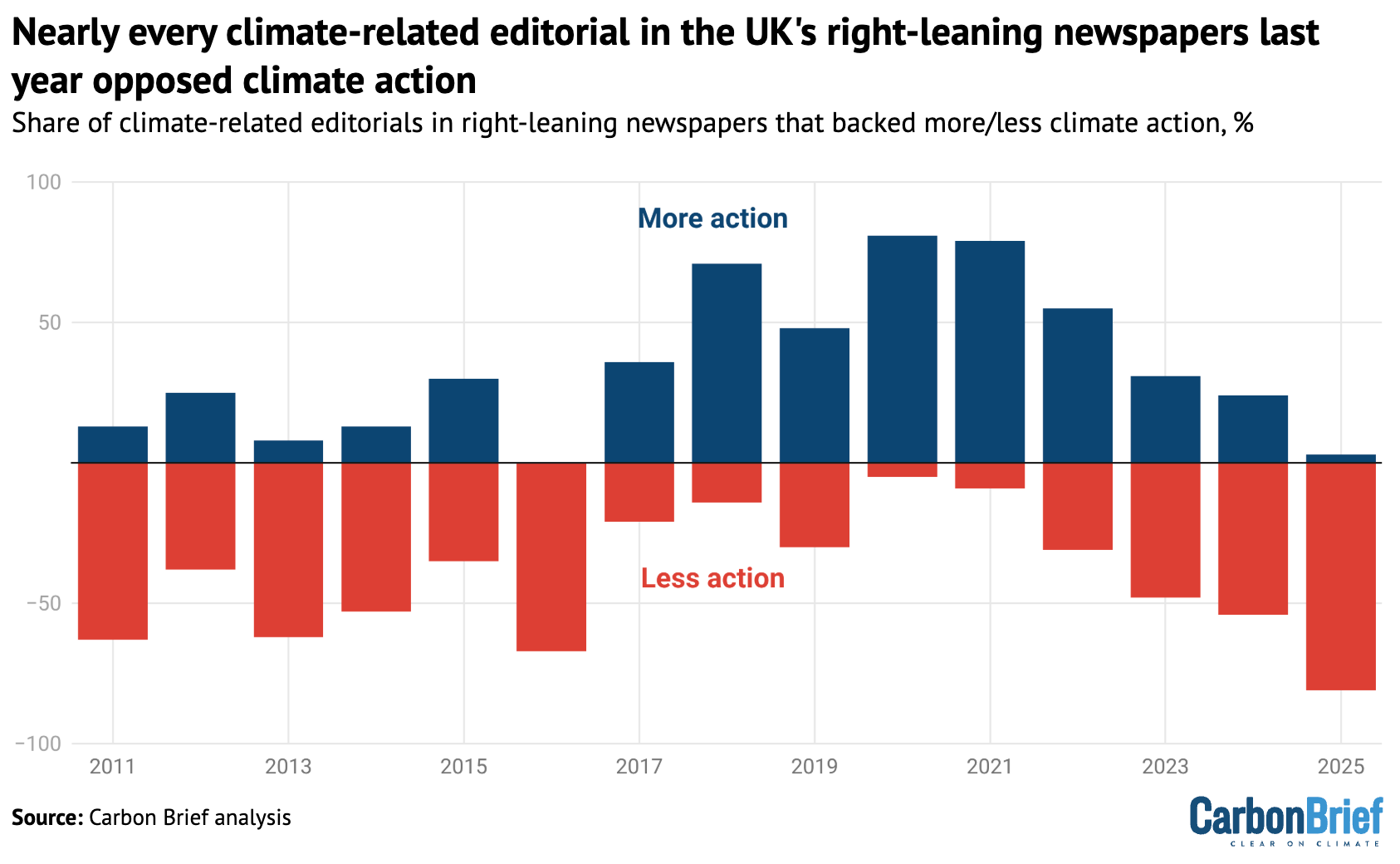

In total, 81% of the climate-related editorials published by right-leaning newspapers in 2025 rejected climate action. As the chart below shows, this is a marked difference from just a few years ago, when the same newspapers showed a surge in enthusiasm for climate action.

That trend had coincided with Conservative governments led by Theresa May and Boris Johnson, which introduced the net-zero goal and were broadly supportive of climate policies.

Notably, none of the editorials opposing climate action in 2025 took a climate-sceptic position by questioning the existence of climate change or the science behind it. Instead, they voiced “response scepticism”, meaning they criticised policies that seek to address climate change.

(The current Conservative leader, Kemi Badenoch, has described herself as “a net-zero sceptic, not a climate change sceptic”. This is illogical as reaching net-zero is, according to scientists, the only way to stop climate change from getting worse.)

In particular, newspapers took aim at “net-zero” as a catch-all term for policies that they deemed harmful. Most editorials that rejected climate action did not even mention the word “climate”, often using “net-zero” instead.

This supports recent analysis by Dr James Painter, a research associate at the University of Oxford, which concluded that UK newspaper coverage has been “decoupling net-zero from climate change”.

This is significant, given strong and broad UK public support for many of the individual climate policies that underpin net-zero. Notably, there is also majority support for the “net-zero by 2050” target itself.

Much of the negative framing by politicians and media outlets paints “net-zero” as something that is too expensive for people in the UK.

In total, 87% of the editorials that opposed climate action cited economic factors as a reason, making this by far the most common justification. Net-zero goals were described as “ruinous” and “costly”, as well as being blamed – falsely – for “driving up energy costs”.

The Sunday Telegraph summarised the view of many politicians and commentators on the right by stating simply that said “net-zero should be scrapped”.

While some criticism of net-zero policies is made in good faith, the notion that climate change can be stopped without reducing emissions to net-zero is incorrect. Alternative policies for tackling climate change are rarely presented by critical editorials.

Moreover, numerous assessments have concluded that the transition to net-zero can be both “affordable” and far cheaper than previously thought.

This transition can also provide significant economic benefits, even before considering the evidence that the cost of unmitigated warming will significantly outweigh the cost of action.

Miliband attacks intensify

Meanwhile, UK newspapers published 112 editorials over the course of 2025 taking personal aim at energy security and net-zero secretary Ed Miliband.

Nearly all of these articles were in right-leaning newspapers, with the Sun alone publishing 51. The Daily Mail, the Daily Telegraph and the Times published most of the remainder.

This trend of relentlessly criticising Miliband personally began last year in the run up to Labour’s election victory. However, it ramped up significantly in 2025, as the chart below shows.

Around 58% of the editorials that opposed climate action used criticism of climate advocates as a justification – and nearly all of these articles mentioned Miliband, specifically.

Editorials denounced Miliband as a “loon” and a “zealot”, suffering from “eco insanity” and “quasi-religious delusions”. Nicknames given to him include “His Greenness”, the “high priest of net-zero” and “air miles Miliband”.

Many of these attacks were highly personal. The Daily Mail, for example, called Miliband “pompous and patronising”, with an “air of moral and intellectual superiority”.

Frequently, newspapers refer to “Ed Miliband’s net-zero agenda”, “Ed Miliband’s swivel-eyed targets” and “Mr Miliband’s green taxes”.

These formulations frame climate policies as harmful measures that are being imposed on people by the energy secretary.

In fact, the Labour government decisively won an election in 2024 with a manifesto that prioritised net-zero policies. Often, the “targets” and “taxes” in question are long-standing policies that were introduced by the previous Conservative government, with cross-party support.

Moreover, the government’s climate policy not only continues to rely on many of the same tools created by previous administrations, it is also very much in line with expert evidence and advice. This is to prioritise the expansion of clean power and to fuel an economy that relies on increasing levels of electrification, including through electric cars and heat pumps.

Despite newspaper editorials regularly calling for Miliband to be “sacked”, prime minister Keir Starmer has voiced his support both for the energy secretary and the government’s prioritisation of net-zero.

In an interview with podcast The Rest is Politics last year, Miliband was asked about the previous Carbon Brief analysis that showed the criticism aimed at him by right-leaning newspapers.

Podcast host Alastair Campbell asked if Miliband thought the attacks were the legacy of his strong stance, while Labour leader, during the Leveson inquiry into the practices of the UK press. Miliband replied:

“Some of these institutions don’t like net-zero and some of them don’t like me – and maybe quite a lot of them don’t like either.”

Renewable backlash

As well as editorial attitudes to climate action in general, Carbon Brief analysed newspapers’ views on three energy technologies – renewables, nuclear power and fracking.

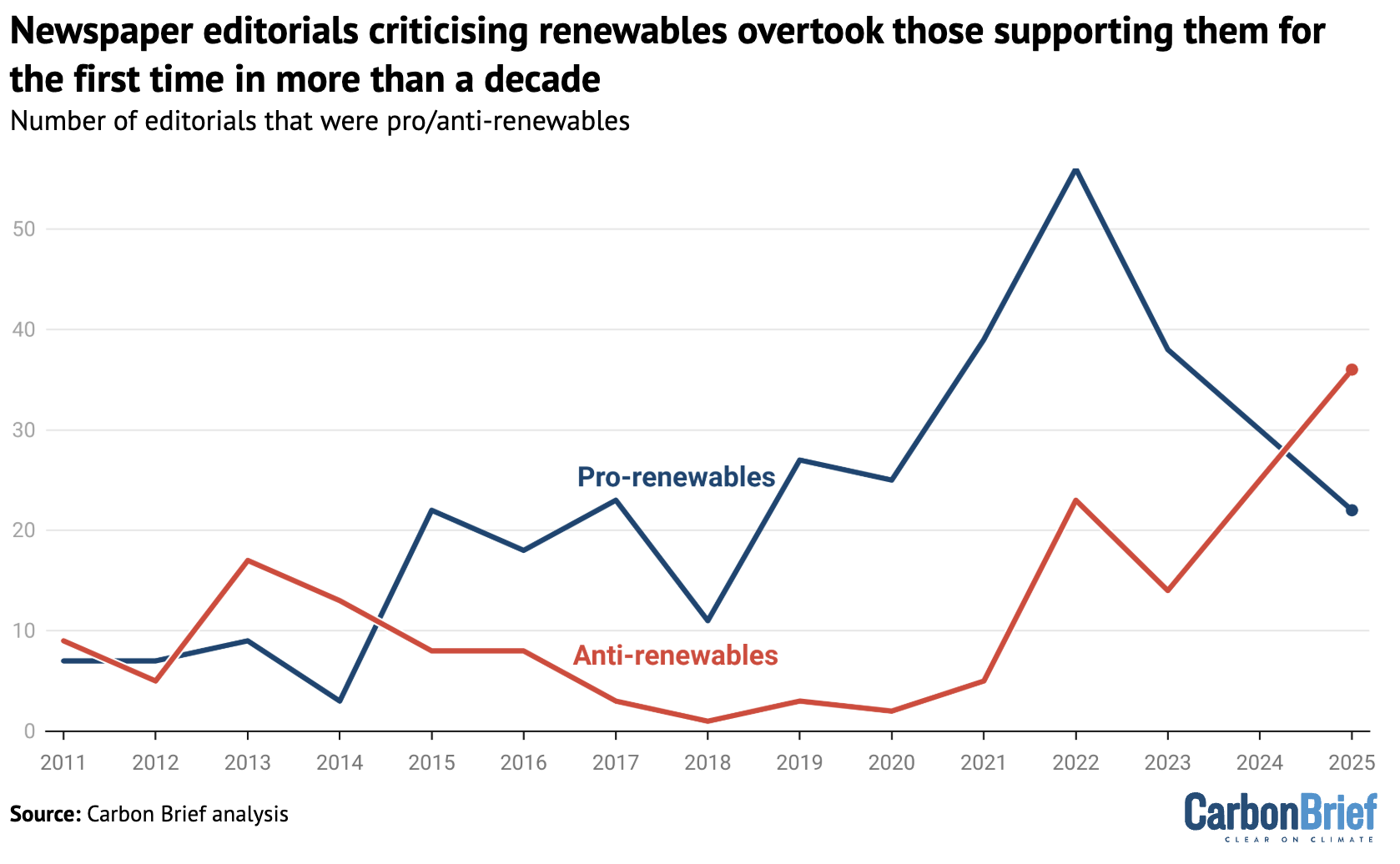

There were 42 newspaper editorials criticising renewable energy in 2025. This meant that, for the first time since 2014, there were more anti-renewables editorials than pro-renewables editorials, as the chart below shows.

As with climate action more broadly, this was a highly partisan issue. The Times was the only right-leaning newspaper that published any editorials supporting renewables.

By far the most common stated reason for opposing renewable energy was that it is “expensive”, with 86% of critical editorials using economic arguments as a justification.

The Sun referred to “chucking billions at unreliable renewables” while the Daily Telegraph warned of an “expensive and intermittent renewables grid”.

At the same time, editorials in supportive publications also used economic arguments in favour of renewables. The Guardian, for example, stressed the importance of building an “affordable clean-energy system” that is “built on renewables”.

There was continued support in right-leaning publications for nuclear power, despite the high costs associated with the technology. In total, there were 20 editorials supporting nuclear power in 2025 – nearly all in right-leaning newspapers – and none that opposed it.

Fracking was barely mentioned by newspapers in 2023 and 2024, after a failed push by the Conservatives under prime minister Liz Truss to overturn a ban on the practice in 2022. This attempt had been accompanied by a surge in supportive right-leaning newspaper editorials.

There was a small uptick of 15 editorials supporting fracking in 2025, as right-leaning newspapers once again argued that it would be economically beneficial.

The Sun urged current Conservative leader Badenoch to make room for this “cheap, safe solution” in her future energy policy. The government plans to ban fracking “permanently”.

North Sea oil and gas remained the main fossil-fuel policy focus, with 30 editorials – all in right-leaning newspapers – that mentioned the topic. Most of the editorials arguing for more extraction from the North Sea also argued for less climate action or opposed renewable energy.

None of these editorials noted that the UK is expected to be significantly less reliant on fossil-fuel imports if it pursues net-zero, than if it rolls back on climate action and attempts to squeeze more out of the remaining deposits in the North Sea.

Methodology

This is a 2025 update of previous analysis conducted for the period 2011-2021 by Carbon Brief in association with Dr Sylvia Hayes, a research fellow at the University of Exeter. Previous updates were published in 2022, 2023 and 2024.

The count of editorials criticising Ed Miliband was not conducted in the original analysis.

The full methodology can be found in the original article, including the coding schema used to assess the language and themes used in editorials concerning climate change and energy technologies.

The analysis is based on Carbon Brief’s editorial database, which is regularly updated with leading articles from the UK’s major newspapers.

The post Analysis: UK newspaper editorial opposition to climate action overtakes support for first time appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Analysis: UK newspaper editorial opposition to climate action overtakes support for first time

-

Greenhouse Gases5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change5 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits