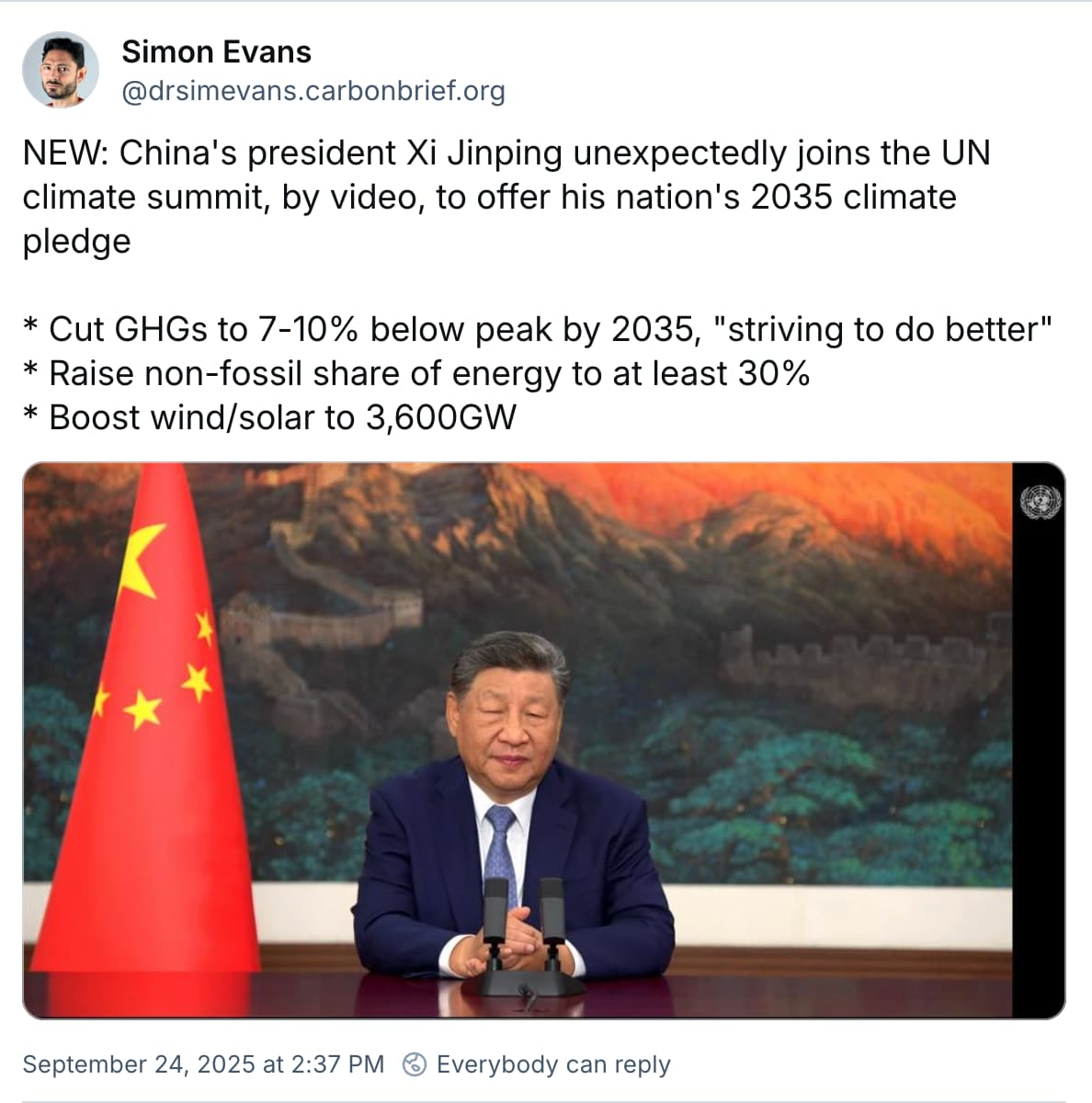

President Xi Jinping has personally pledged to cut China’s greenhouse gas emissions to 7-10% below peak levels by 2035, while “striving to do better”.

This is China’s third pledge under the Paris Agreement, but is the first to put firm constraints on the country’s emissions by setting an “absolute” target to reduce them.

China’s leader spoke via video to a UN climate summit in New York organised by secretary general António Guterres, making comments seen as a “veiled swipe” at US president Donald Trump.

The headline target, with its undefined peak-year baseline, falls “far short” of what would have been needed to help limit warming to well-below 2C or 1.5C, according to experts.

Moreover, Xi’s pledge for non-fossil fuels to make up 30% of China’s energy is far below the latest forecasts, while his goal for wind and solar capacity to reach 3,600 gigawatts (GW) implies a significant slowdown, relative to recent growth.

Overall, the targets for China’s new 2035 “nationally determined contribution” (NDC) under the Paris Agreement have received a lukewarm response, described as “conservative”, “too weak” and as not reflecting the pace of clean-energy expansion on the ground.

Nevertheless, Li Shuo, director of the China Climate Hub at the Asia Society Policy Institute (ASPI), tells Carbon Brief that the pledge marks a “big psychological jump for the Chinese”, shifting from targets that constrained emissions growth to a requirement to cut them.

Below, Carbon Brief unpacks what China’s new targets mean for its emissions and energy use, pending further details once its full NDC is formally published in full.

Carbon Brief is hosting a webinar about China’s new climate goals on Monday. Register here.

- What is in China’s new climate pledge?

- What is China’s first ‘absolute’ emissions reduction target?

- What has China pledged on non-fossil energy, coal and renewables?

- What does China say about non-CO2 emissions?

What is in China’s new climate pledge?

For now, the only available information on China’s 2035 NDC is the short series of pledges in Xi’s speech to the UN.

(This article will be updated once the NDC itself is published on the UN’s website.)

Xi’s speech is the first time his country has promised to place an absolute limit on its greenhouse gas emissions, marking a significant shift in approach.

Xi had previously pledged that China would peak its carbon dioxide (CO2) emissions “before 2030”, without defining at what level, reaching “carbon neutrality” by 2060.

He also outlined a handful of other key targets for 2035, shown in the table below against the goals set in previous NDCs.

| Indicators | Targets for 2035 | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| First NDC (2016) | NDC 2.0 (2021) | NDC 3.0 (2025) | |

| Emissions target | Peak CO2 “around 2030”, “making best efforts to peak early” | Peak CO2 “before 2030” and “achieve carbon neutrality before 2060” | Cut GHGs to 7-10% below peak levels by 2035 |

| CO2 intensity reduction (compared to 2005) | 60-65% | >65% | – |

| Non-fossil share in primary energy mix | Around 20% | Around 25% | 30% |

| Forest stock volume increase (compared to 2005) | Around 4.5bn cubic metres | 6bn cubic metres | 11bn cubic metres |

| Installed capacity of wind and solar power | – | >1,200GW | >3,600GW |

In his speech, Xi also said that, by 2035, “new energy vehicles” would be the “mainstream” for new vehicle sales, China’s national carbon market would cover all “major high-emission industries” and that a “climate-adaptive society” would be “basically established”.

This is the first time that China’s targets will cover the entire economy and all greenhouse gases (GHGs), a move that has been long signalled by Chinese policymakers.

In 2023, the joint China-US Sunnylands statement, released during the Biden administration, had said that both countries’ 2035 NDCs “will be economy-wide, include all GHGs and reflect…[the goal of] holding the increase in global average temperature to well-below 2C”.

Subsequently, the world’s first global stocktake, issued at COP28 in Dubai, “encourage[d]” all countries to submit “ambitious, economy-wide emission reduction targets, covering all GHGs, sectors and categories…aligned with limiting global warming to 1.5C”.

Responding to this the following year, executive vice-premier and climate lead Ding Xuexiang stated at COP29 in Baku that China’s 2035 climate pledge would be economy-wide and cover all GHGs. (His remarks did not mention alignment with 1.5C.)

This was reiterated by Xi at a climate meeting between world leaders in April 2025.

The absolute target for all greenhouse gases marks a turning point in China’s emissions strategy. Until now, China’s emissions targets have largely focused on carbon intensity, the emissions per unit of GDP, a metric that does not directly constrain emissions as a whole.

The change aligns with China’s broader shift from “dual control of energy” towards “dual control of carbon”, a policy that replaces China’s current tradition of setting targets for energy intensity and total energy consumption, with carbon intensity and carbon emissions.

Under the policy, in the 15th five-year plan period (2026-2030), China will continue to centre carbon intensity as its main metric for emissions reduction. After 2030, an absolute cap on carbon emissions will become the predominant target.

What is China’s first ‘absolute’ emissions reduction target?

In his UN address, Xi pledged to cut China’s “economy-wide net greenhouse gas emissions” to 7-10% below peak levels by 2035, while “striving to do better”.

This means the target includes not just CO2, but also methane, nitrous oxide (N2O) and F-gases, all of which make significant contributions to global warming. (See: What does China say about non-CO2 emissions?)

The reference to “economy-wide net” emissions means that the target refers to the total of China’s emissions, from all sources, minus removals, which could come from natural sources, such as afforestation, or via “carbon dioxide removal” technologies.

Outlining the targets, Xi told the UN summit that they represented China’s “best efforts, based on the requirements of the Paris Agreement”. He added:

“Meeting these targets requires both painstaking efforts by China itself and a supportive and open international environment. We have the resolve and confidence to deliver on our commitments.”

China has a reputation for under-promising and over-delivering.

Prof Wang Zhongying, director-general of the Energy Research Institute, a Chinese government-affilitated thinktank, told Carbon Brief in an interview at COP26 that China’s policy targets represent a “bottom line”, which the policymakers are “definitely certain” about meeting. He views this as a “cultural difference”, relative to other countries.

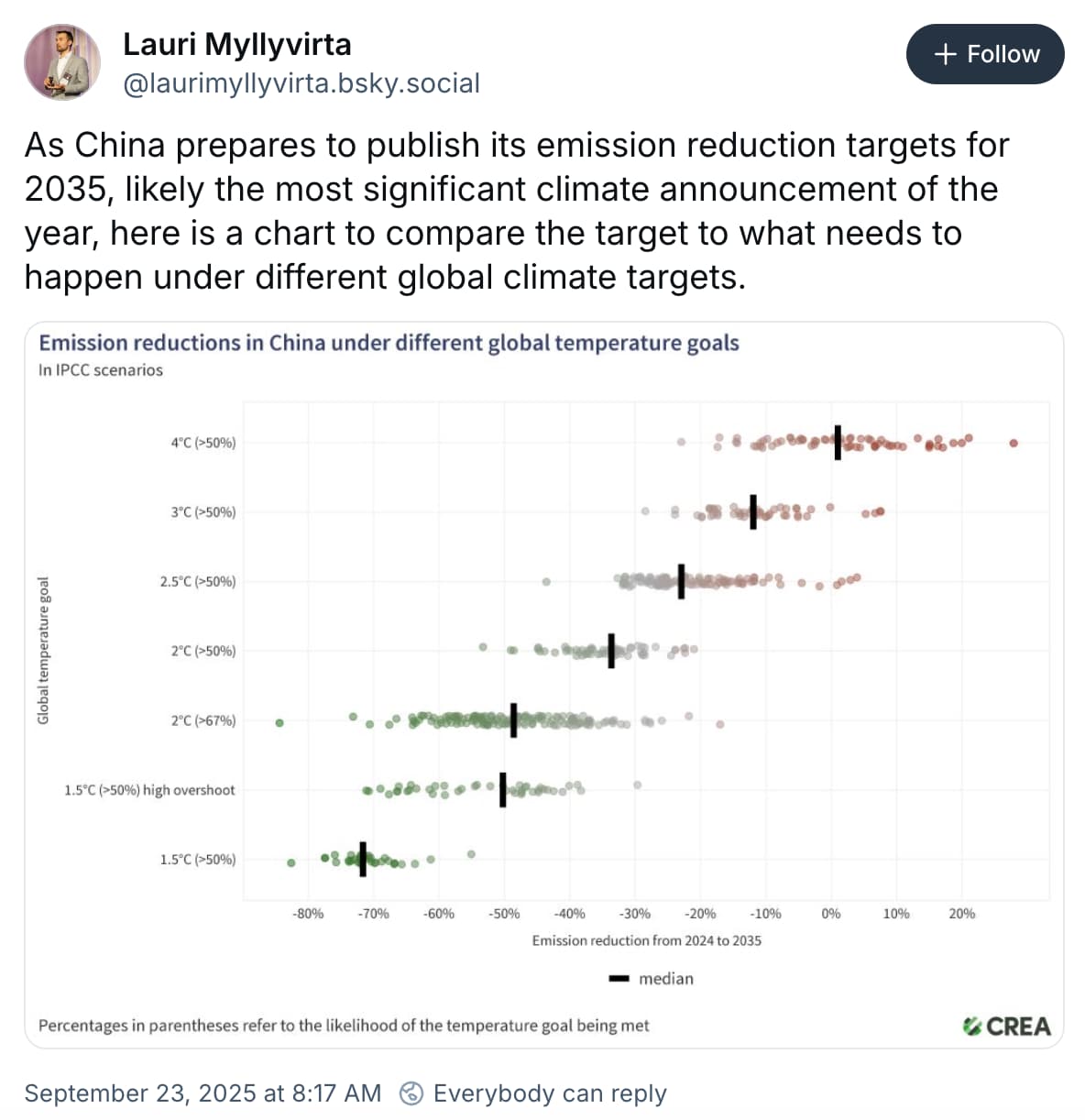

The headline target announced by Xi this week has, nevertheless, been seen as falling far short of what was needed.

A series of experts had previously told Carbon Brief that a 30% reduction from 2023 levels was the absolute minimum contribution towards a 1.5C global limit, with many pointing to much larger reductions in order to be fully aligned with the 1.5C target.

The figure below illustrates how China’s 2035 target stacks up against these levels.

(Note that the timing and level of peak emissions is not defined by China’s targets. The pledge trajectory is constrained by China’s previous targets for carbon intensity and expected GDP growth, as well as the newly announced 7-10% range. It is based on total emissions, excluding removals, which are more uncertain.)

Analysis by the Asia Society Policy Institute also found that China’s GHG emissions “must be reduced by at least 30% from the peak through 2035” in order to align with 1.5C warming.

It said that this level of ambition was achievable, due to China’s rapid clean-energy buildout and signs that the nation’s emissions may have already reached a peak.

Similarly, the International Energy Agency (IEA) said last October that implementing the collective goals of the first stocktake – such as tripling renewables by 2030 – as well as aligning near-term efforts with long-term net-zero targets, implied emissions cuts of 35-60% by 2035 for emerging market economies, a grouping that includes China.

In response to these sorts of numbers, Teng Fei, deputy director of Tsinghua University’s Institute of Energy, Environment and Economy, previously described a 30% by 2035 target as “extreme”, telling Agence France-Presse that this would be “too ambitious to be achievable”, given uncertainties around China’s current development trajectory.

In contrast, a January 2025 academic study, co-authored by researchers from Chinese government institutions and top universities and understood to have been influential in Beijing’s thinking, argued for a pledge to cut energy-related CO2 emissions “by about 10% compared with 2030”, estimating that emissions would peak “between 2028 and 2029”.

(Other assessments have pegged relevant indicators, such as emissions and coal consumption, as peaking in 2028 at the earliest.)

The relatively modest emissions reduction range pledged by Xi, as well as the uncertainty introduced by avoiding a definitive baseline year, has disappointed analysts.

In a note responding to Xi’s pledges, Li Shuo and his ASPI colleague Kate Logan write that he has “misse[d] a chance at leadership”.

Li tells Carbon Brief that factors behind the modest target include the “domestic economic slowdown and uncertain economic prospects, the weakening global climate momentum and the turbulent geopolitical environment”. He adds:

“I also think it is a big psychological jump for the Chinese, shifting for the first time after decades of rapid growth, from essentially climate targets that meant to contain further increase to all of a sudden a target that forces emissions to go down.”

Instead of a target consistent with limiting warming to 1.5C, China’s 2035 pledge is more closely aligned with 3C of warming, according to analysis by CREA’s Lauri Myllyirta.

Climate Action Tracker says that China’s target is “unlikely to drive down emissions”, because it was already set to achieve similar reductions under current policies.

What has China pledged on non-fossil energy, coal and renewables?

In addition to a headline emissions reduction target, Xi also pledged to expand non-fossil fuels as a share of China’s energy mix and to continue the rollout of wind and solar power.

This continues the trend in China’s previous NDC.

Notably, however, Xi made no mention of efforts to control coal in his speech.

In its second NDC, focused on 2030, China had pledged to “strictly control coal-fired power generation projects”, as well as “strictly limit” coal consumption between 2021-2025 and “phase it down” between 2026-2030. It also said China “will not build new coal-fired power projects abroad”.

It remains to be seen if coal is addressed in China’s full NDC for 2035.

The 2030 NDC also stated that China would “increase the share of non-fossil fuels in primary energy consumption to around 25%” – and Xi has updated this to 30% by 2035.

These targets are shown in the figure below, alongside recent forecasts from the Sinopec Economics and Development Research Institute, which estimated that non-fossil fuel energy could account for 27% of primary energy consumption in 2030 and 36% in 2035.

As such, China’s targets for non-fossil energy are less ambitious than the levels implied by current expectations for growth in low-carbon sources.

In a recent meeting with the National People’s Congress Standing Committee – the highest body of China’s state legislature – environment minister Huang Runqiu said that progress on China’s earlier target for increasing non-fossil energy’s share of energy consumption was “broadly in line” with the “expected pace” of the 2030 NDC.

On wind and solar, China’s 2030 NDC had pledged to raise installed capacity to more than 1,200GW – a target that analysts at the time told Carbon Brief was likely to be beaten. It was duly met six years early, with capacity standing at 1,680GW as of the end of July 2025.

Xi has set a 2035 target of reaching 3,600GW of wind and solar capacity.

This looks ambitious, relative to other countries and global capacity of around 3,000GW in total as of 2024, but represents a significant slowdown from the recent pace of growth.

Given its current capacity, China would need to install around 200GW of new wind and solar per year and 2,000GW in total to reach the 2035 target. Yet it installed 360GW in 2024 and 212GW of solar alone in the first half of this year.

Myllyvirta tells Carbon Brief this pace of additions is “not enough to even peak emissions [in the power sector] unless energy demand growth slows significantly”.

While the pace of demand growth is a key uncertainty, a recent study by Michael R Davidson, associate professor at the University of California, San Diego, with colleagues at Tsinghua University, suggested that deploying 2,910-3,800GW of wind and solar by 2035 would be consistent with a 2C warming pathway.

Davidson tells Carbon Brief that “most experts within China do not see the [recent] 300+GW per year growth as sustainable”. Still, he adds that the lower levels outlined in his study could be consistent with cutting power-sector emissions 40% by 2035, subject to caveats around whether new capacity is well-sited and appropriately integrated:

“We found that 40% emissions reductions in the power sector can be supported by 3,000-3,800GW wind and solar capacity [by 2035]. Most of the capacity modeling really depends on integration and quality of resources.”

Renewable energy’s share of consumption in China has lagged behind its record capacity installations, largely due to challenges with updating grid infrastructure and economic incentives that lock in coal-fired power.

In Davidson’s study, capacity growth of up to 3,800GW would see wind and solar reaching around 40% of total power generation by 2030 and 50% by 2035.

Meanwhile, China will need to install around 10,000GW of wind and solar capacity to reach carbon neutrality by 2060, according to a separate report by the Energy Research Institute, a Chinese government-affilitated thinktank.

What does China say about non-CO2 emissions?

This is the first time that one of China’s NDC pledges has explicitly covered the emissions from non-CO2 GHGs.

However, while Xi’s speech made clear that China’s headline emissions goal for 2035 will cover non-CO2 gases, such as methane, nitrous oxide and F-gases, he did not give further details on whether the NDC would set specific targets for these emissions.

In China’s 2030 NDC, the country stated it would “step up the control of key non-CO2 GHG emissions”, including through new control policies, but did not include a quantitative emissions reduction target.

In preparation for a comprehensive greenhouse gas emissions target, China has issued action plans for methane, hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs, one type of F-gas) and nitrous oxide.

The nitrous oxide action plan, published earlier this month, called for emissions per unit of production for specific chemicals to decrease to a “world-leading level” by 2030, but did not set overarching limits.

Similarly, the overarching methane action plan, issued in late 2023, listed several key tasks for reducing emissions in the energy, agriculture and waste sectors, but lacked numerical targets for emissions reduction.

A subsequent rule change in December 2024 tightened waste gas requirements for coal mines. Under the new rules, Reuters reports, any coal mine that releases “emissions with methane content of 8% or higher” must capture the gas, and either use or destroy it – down from a previous threshold of 30%.

But analysts believe that the true challenge of coal-mine methane emissions may come from abandoned mines, which, one study found, have surged in the past 10 years and will likely overtake emissions from active coal mines to become the prime source of methane emissions in the coal sector.

As the demand for coal could be facing a “structural decline”, the number of abandoned mines is expected to grow significantly.

Meanwhile, the HFC plan did set quantitative targets. The country aims to lower HFC production by 2029 by 10% from a 2024 baseline of 2GtCO2e, while consumption would also be reduced 10% from a baseline of 0.9gtCO2e in this timeframe – in line with China’s obligations under the Kigali Amendment to the Montreal Protocol on ozone protection.

From 2026, China will “prohibit” the production of fridges and freezers using HFC refrigerants.

However, the action plan does not govern China’s exports of products that use HFCs – a significant source of emissions.

The post Q&A: What does China’s new Paris Agreement pledge mean for climate action? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Q&A: What does China’s new Paris Agreement pledge mean for climate action?

Climate Change

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of America’s Broken Health Care System

American farmers are drowning in health insurance costs, while their German counterparts never worry about medical bills. The difference may help determine which country’s small farms are better prepared for a changing climate.

Samantha Kemnah looked out the foggy window of her home in New Berlin, New York, at the 150-acre dairy farm she and her husband, Chris, bought last year. This winter, an unprecedented cold front brought snowstorms and ice to the region.

On the Farm, the Hidden Climate Cost of the Broken U.S. Health Care System

Climate Change

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Two Utah Congress members have introduced a resolution that could end protections for Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument. Conservation groups worry similar maneuvers on other federal lands will follow.

Lawmakers from Utah have commandeered an obscure law to unravel protections for the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument, potentially delivering on a Trump administration goal of undoing protections for public conservation lands across the country.

A Little-Used Maneuver Could Mean More Drilling and Mining in Southern Utah’s Redrock Country

Climate Change

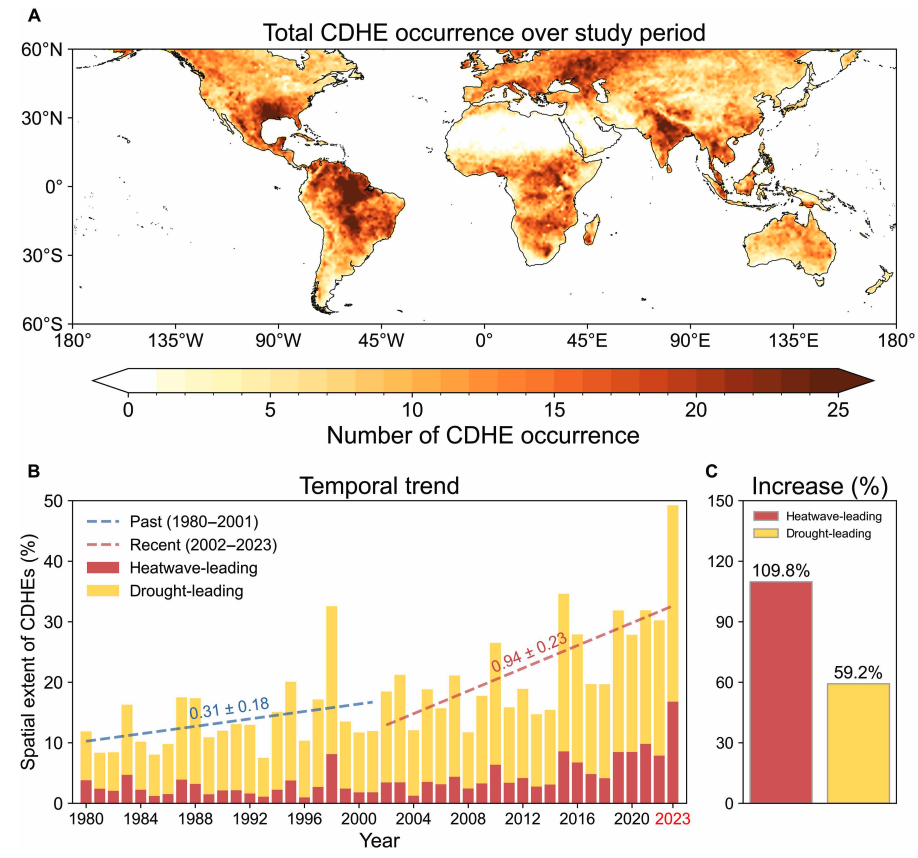

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

Drought and heatwaves occurring together – known as “compound” events – have “surged” across the world since the early 2000s, a new study shows.

Compound drought and heat events (CDHEs) can have devastating effects, creating the ideal conditions for intense wildfires, such as Australia’s “Black Summer” of 2019-20 where bushfires burned 24m hectares and killed 33 people.

The research, published in Science Advances, finds that the increase in CDHEs is predominantly being driven by events that start with a heatwave.

The global area affected by such “heatwave-led” compound events has more than doubled between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, the study says.

The rapid increase in these events over the last 23 years cannot be explained solely by global warming, the authors note.

Since the late 1990s, feedbacks between the land and the atmosphere have become stronger, making heatwaves more likely to trigger drought conditions, they explain.

One of the study authors tells Carbon Brief that societies must pay greater attention to compound events, which can “cause severe impacts on ecosystems, agriculture and society”.

Compound events

CDHEs are extreme weather events where drought and heatwave conditions occur simultaneously – or shortly after each other – in the same region.

These events are often triggered by large-scale weather patterns, such as “blocking” highs, which can produce “prolonged” hot and dry conditions, according to the study.

Prof Sang-Wook Yeh is one of the study authors and a professor at the Ewha Womans University in South Korea. He tells Carbon Brief:

“When heatwaves and droughts occur together, the two hazards reinforce each other through land-atmosphere interactions. This amplifies surface heating and soil moisture deficits, making compound events more intense and damaging than single hazards.”

CDHEs can begin with either a heatwave or a drought.

The sequence of these extremes is important, the study says, as they have different drivers and impacts.

For example, in a CDHE where the heatwave was the precursor, increased direct sunshine causes more moisture loss from soils and plants, leading to a drought.

Conversely, in an event where the drought was the precursor, the lack of soil moisture means that less of the sun’s energy goes into evaporation and more goes into warming the Earth’s surface. This produces favourable conditions for heatwaves.

The study shows that the majority of CDHEs globally start out as a drought.

In recent years, there has been increasing focus on these events due to the devastating impact they have on agriculture, ecosystems and public health.

In Russia in the summer of 2010, a compound drought-heatwave event – and the associated wildfires – caused the death of nearly 55,000 people, the study notes.

The record-breaking Pacific north-west “heat dome” in 2021 triggered extreme drought conditions that caused “significant declines” in wheat yields, as well as in barley, canola and fruit production in British Columbia and Alberta, Canada, says the study.

Increasing events

To assess how CDHEs are changing, the researchers use daily reanalysis data to identify droughts and heatwaves events. (Reanalysis data combines past observations with climate models to create a historical climate record.) Then, using an algorithm, they analyse how these events overlap in both time and space.

The study covers the period from 1980 to 2023 and the world’s land surface, excluding polar regions where CDHEs are rare.

The research finds that the area of land affected by CDHEs has “increased substantially” since the early 2000s.

Heatwave-led events have been the main contributor to this increase, the study says, with their spatial extent rising 110% between 1980-2001 and 2002-23, compared to a 59% increase for drought-led events.

The map below shows the global distribution of CDHEs over 1980-2023. The charts show the percentage of the land surface affected by a heatwave-led CDHE (red) or a drought-led CDHE (yellow) in a given year (left) and relative increase in each CDHE type (right).

The study finds that CDHEs have occurred most frequently in northern South America, the southern US, eastern Europe, central Africa and south Asia.

Threshold passed

The authors explain that the increase in heatwave-led CDHEs is related to rising global temperatures, but that this does not tell the whole story.

In the earlier 22-year period of 1980-2001, the study finds that the spatial extent of heatwave-led CDHEs rises by 1.6% per 1C of global temperature rise. For the more-recent period of 2022-23, this increases “nearly eightfold” to 13.1%.

The change suggests that the rapid increase in the heatwave-led CDHEs occurred after the global average temperature “surpasse[d] a certain temperature threshold”, the paper says.

This threshold is an absolute global average temperature of 14.3C, the authors estimate (based on an 11-year average), which the world passed around the year 2000.

Investigating the recent surge in heatwave-leading CDHEs further, the researchers find a “regime shift” in land-atmosphere dynamics “toward a persistently intensified state after the late 1990s”.

In other words, the way that drier soils drive higher surface temperatures, and vice versa, is becoming stronger, resulting in more heatwave-led compound events.

Daily data

The research has some advantages over other previous studies, Yeh says. For instance, the new work uses daily estimations of CDHEs, compared to monthly data used in past research. This is “important for capturing the detailed occurrence” of these events, says Yeh.

He adds that another advantage of their study is that it distinguishes the sequence of droughts and heatwaves, which allows them to “better understand the differences” in the characteristics of CDHEs.

Dr Meryem Tanarhte is a climate scientist at the University Hassan II in Morocco, and Dr Ruth Cerezo Mota is a climatologist and a researcher at the National Autonomous University of Mexico. Both scientists, who were not involved in the study, agree that the daily estimations give a clearer picture of how CDHEs are changing.

Cerezo-Mota adds that another major contribution of the study is its global focus. She tells Carbon Brief that in some regions, such as Mexico and Africa, there is a lack of studies on CDHEs:

“Not because the events do not occur, but perhaps because [these regions] do not have all the data or the expertise to do so.”

However, she notes that the reanalysis data used by the study does have limitations with how it represents rainfall in some parts of the world.

Compound impacts

The study notes that if CDHEs continue to intensify – particularly events where heatwaves are the precursors – they could drive declining crop productivity, increased wildfire frequency and severe public health crises.

These impacts could be “much more rapid and severe as global warming continues”, Yeh tells Carbon Brief.

Tanarhte notes that these events can be forecasted up to 10 days ahead in many regions. Furthermore, she says, the strongest impacts can be prevented “through preparedness and adaptation”, including through “water management for agriculture, heatwave mitigation measures and wildfire mitigation”.

The study recommends reassessing current risk management strategies for these compound events. It also suggests incorporating the sequences of drought and heatwaves into compound event analysis frameworks “to enhance climate risk management”.

Cerezo-Mota says that it is clear that the world needs to be prepared for the increased occurrence of these events. She tells Carbon Brief:

“These [risk assessments and strategies] need to be carried out at the local level to understand the complexities of each region.”

The post Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Heatwaves driving recent ‘surge’ in compound drought and heat extremes

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits