Welcome to Carbon Brief’s Cropped.

We handpick and explain the most important stories at the intersection of climate, land, food and nature over the past fortnight.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s fortnightly Cropped email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Amazon affairs

DRY SPELL: Climate change made last year’s agricultural drought in the Amazon around 30 times more likely to occur, according to a new rapid attribution study covered by Mongabay. The El Niño climate pattern “played a much smaller role” than many had assumed, the outlet said. World Weather Attribution scientists analysed data from the Amazon region between June and December last year, finding that both El Niño and climate change “contributed to reduced rainfall” during these months. But climate change “also led to high temperatures, significantly increasing water evaporation from plants and soils”, the outlet added. The report authors “predict that dry spells in the Amazon will become more frequent and harsher” under continued warming, Mongabay said.

CRIME COOPERATION: A $1.8m Amazon rainforest security centre will open in Manaus, Brazil in the coming months, Climate Home News reported. The centre is financed through the Amazon Fund and will “bring together Amazon nations in policing the rainforest, sharing intelligence and chasing criminals”, the outlet said. Climate Home News quoted Humberto Freire, head of the Brazil federal police’s environment and Amazon department, who said the centre will “fight drug trafficking and the smuggling of timber, fish and exotic animals, as well as deforestation and other environmental crimes”. It will also focus on illegal gold mining on Indigenous land, the outlet said.

LAND CONFLICT: Meanwhile, Brazil’s president, Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva, said the federal government will “help resolve” a land conflict between Indigenous people and farmers that led to the fatal shooting of a tribal leader, Reuters reported. Maria Fatima de Andrade was shot and killed after 200 land owners tried to “evict an Indigenous community” from a farm in the state of Bahia and take the land, which is claimed by the Pataxó tribe, the newswire said. Another leader was also shot and brought to hospital, Reuters said, noting that the incident “underlines years of tensions between Brazil’s Indigenous peoples and agricultural settlers over land rights”. The country’s minister for Indigenous peoples, Sonia Guajajara, said the attack was “unacceptable”, the newswire added.

Offsets scrutinised

EU BAN: Labelling products and services as “climate neutral” or “climate positive” based on the use of carbon offsets will be banned in the EU from 2026, the Guardian reported. Carbon offsets involve a polluting entity, such as an airline, paying for emissions to be reduced elsewhere, such as by preventing deforestation. Companies often use carbon-offsetting to make claims that their products are “net-zero” or “environmentally friendly”, but evidence – previously set out in detail by Carbon Brief – shows these can be exaggerated or misleading. On 17 January, members of the European parliament voted to outlaw the use of terms such as “environmentally friendly”, “natural”, “biodegradable”, “climate neutral” or “eco” without evidence. The European parliament also introduced a total ban on using carbon-offsetting to back up such claims, the Guardian reported. The NGO Carbon Market Watch called the move “a big step towards more honest commercial practices and more informed European consumers”.

GUYANA CREDITS: Elsewhere, the Financial Times reported on Guyana’s plans to generate $3bn from forest carbon offset schemes by the end of the decade. Forests currently cover 85% of the South American country’s land surface, the FT said, with the government estimating they could generate credits representing 19.5bn tonnes of CO2 – more than the annual emissions of China. However, offsetting plans could be put at risk by conflict with neighbouring Venezuela, which has threatened to annex more than half of Guyana’s territory, the FT said. It added that most of Guyana’s forests are in the mineral-rich region of Essequibo, “a tract of Amazon jungle that would be a prime target for Venezuelan loggers and miners in the event of a takeover”.

COOKSTOVE CONTROVERSY: Finally, Heatmap was among several publications covering a new study finding that carbon offset schemes using so-called “clean” cookstoves are “kind of bogus”. Clean cookstove schemes involve the distribution of more efficient cooking equipment, with the goal of cutting reliance on traditional fuels, such as firewood – leading to lower emissions. The study from researchers at the University of California, Berkeley, found that cookstove projects have generated, on average, nine times more carbon credits than they should have, Heatmap reported. The research was published in the journal Nature Sustainability.

Spotlight

French farmers and the far right

In this spotlight, Carbon Brief looks at the ongoing EU farmer protests and how far-right political groups could latch on to the outrage ahead of the European parliament elections in June.

Farmers have used tractors to blockade the streets of Berlin, Brussels and Bucharest in recent weeks. Farmers across the EU have been protesting against “competition from cheaper imports”, tightening environmental rules and rising production costs, according to Reuters.

This week, the French farmer protests escalated. Hundreds of tractors blocked off major roads into the country’s capital in what has been dubbed the “siege of Paris” by many media outlets, including BBC News. President Emmanuel Macron is “scrambling to end an escalating political and social crisis”, the Times said.

According to Le Monde, farmers are raising issues around “pesticides, free-trade agreements and wages”. France is an EU agricultural powerhouse, producing huge amounts of meat, dairy and wheat each year.

The nation’s newly appointed prime minister, Gabriel Attal, announced some concessions to farmers, including simplified technical procedures and a “progressive end to diesel fuel taxes for farm vehicles”, the Associated Press reported.

But the two main farmers’ unions said these measures did not go far enough and vowed to continue the protests.

The protests are the “first big test” of Attal’s leadership, Bloomberg noted. And, just months out from the European parliament elections, Euractiv said they are also the “first major political test for EU election candidates in France”.

Ahead of these elections, Politico said that right-wing parties in countries – such as France, Italy, the Netherlands and Germany – are “piggybacking on farmers’ noisy outrage”. Recent polling has suggested that there could be a “sharp turn to the right” in the June vote, Deutsche Welle reported.

Dr Gilles Ivaldi, a politics researcher at Sciences Po who has examined the far right in Europe, said that right-wing groups may use the farmer protests to “boost their electoral support” in France and elsewhere. He told Carbon Brief:

“What we see, particularly in France, is that the far right is seeking to capitalise on public discontent with the impact of the green transition, not only among farmers but also in social groups affected most by the economic cost of environmental policies.”

He said the French far right is “clearly trying to instrumentalise” the farmer protests to “mobilise against the government and the EU”. Sky News said the protests “are being seized upon by various groups”, including Marine Le Pen’s right-wing Rassemblement National party.

But Ivaldi noted that the far right’s EU election focus will mostly remain on topics such as immigration, the economy, the future of the EU and the bloc’s Green Deal. The “main factors” behind a potential right-wing surge will not come from agriculture alone. He added:

“Far-right parties are currently capitalising on the economic crisis and rise in prices, on the immigration issue, particularly growing concerns about the massive influx of refugees in Germany and, more broadly, the many anxieties caused by the war in Ukraine and geopolitical instability.”

News and views

LET’S EAT BALANCED’: A £4m advertising campaign aimed at convincing young people to eat more meat and dairy has been released in the UK, with support from the government, DeSmog reported. Timed to coincide with Veganuary (a popular challenge where people go vegan for January), the “Let’s Eat Balanced” campaign – voiced by British comedian Richard Ayoade – targets cinema screens, TVs, newspapers, social media channels and major supermarkets, DeSmog said. The campaign attempts to communicate the health benefits of eating meat and dairy, which “flies in the face of science”, experts told DeSmog. It was developed by the PR agency Ogilvy, which counts BP as a former client, and is run by the Agriculture and Horticulture Development Board, a UK government-appointed board funded by farmers’ levies.

AT SEA: Chile and Palau became the first countries to officially sign off on the High Seas Treaty, Euronews Green reported. Palau was the first to ratify the treaty governing the sustainable use and conservation of international waters since it was agreed last March, the outlet said. The Chilean senate “unanimously” voted in favour of ratification, which will become official “once it is published in the government’s official journal”. The outlet quoted Rebecca Hubbard, director of the High Seas Alliance, who said she hopes Palau “inspires” others to “redouble their efforts to ratify the treaty without delay so that it can enter force as soon as possible” once 60 nations sign off.

COLOMBIA FIRES: Colombia, due to host the biodiversity summit COP16 later this year, is currently battling intense fires in the mountains around the capital city of Bogotá, as dozens of other blazes have burned across the country, the New York Times reported. The president, Gustavo Petro, has declared a national disaster and asked for international help fighting the fires amid the country’s hottest January in three decades, according to the publication. It comes after the UN Convention on Biological Diversity announced that six cities in Colombia have expressed interest in hosting COP16. It is not yet clear if the fire emergency could affect Colombia’s ability to host the summit.

TAKE OFF: The world’s first plant using ethanol partly made with corn to produce “sustainable aviation fuel” opened in the US, Bloomberg reported. The $200m facility in Georgia plans to use the ethanol made from “American-grown corn, as well as from advanced technologies”, the outlet said. The facility’s opening spurred industry groups in Iowa – the US state that produces the most corn – to warn farmers and ethanol producers that they risk “missing out on the chance to significantly profit from the developing market for sustainable aviation fuel”, the outlet said. A 2022 study found that corn-based ethanol is likely more carbon-intensive overall than petrol, Reuters previously reported.

HUNT FOR POWER: Climate Home News investigated lithium mining in Zimbabwe, where Chinese companies have “flocked” to secure supplies of the lightweight metal, which is crucial for electric vehicle batteries. Lithium mining “brought the promise of jobs and a better life” for some, the piece outlined, but the country’s “poor progress on establishing robust resource governance” could prevent local communities from “seeing any of the benefits”. The country’s president, Emmerson Mnangagwa, “aspires to turn Zimbabwe into a battery manufacturing hub” to help “catapult the country into an upper-middle-income economy by 2030”, the outlet said.

CAMBODIA DEFORESTATION: A Mongabay investigation alleged that a vast forested wildlife sanctuary in Cambodia is being put at risk by mining concessions granted by the government to a “timber baron” who has previously been sanctioned over corruption in relation to natural resource extraction. In 2023, the Cambodian government announced a ban on extractive practices inside the Prey Lang Wildlife Sanctuary, a “sprawling carbon sink” home to 250,000 Indigenous peoples, according to Mongabay. However, the government made an exemption for companies that had already been awarded contracts, it added. This included the mining company of Try Pheap, “a powerful tycoon and adviser to the previous prime minister”, Mongabay said. Mongabay was unable to make contact with the Cambodian government or representatives of Try Pheap, despite repeated attempts.

Watch, read, listen

TREE GRIEF: Al Jazeera spoke to Palestinians who are grieving the loss of their olive trees, which have long been a symbol of the Palestinian spirit, amid Israel’s assault on Gaza.

HIT THE WAVES: The Climate Question, a BBC podcast, looked towards Northern Ireland and South Korea to see why tidal power is not more commonly used in renewable energy.

TINY WILD CAT: A long read by Mongabay explored how conservationists are working to save the guina, the Americas’ smallest wild cat species, native to Chile and Argentina.

‘BLACK MOSS’: The South China Morning Post examined the Chinese new year staple “fat choy” and how its overharvesting has turned parts of China “into desert”.

New science

Atmospheric CO2 emissions and ocean acidification from bottom-trawling

Frontiers in Marine Science

Bottom-trawling – the fishing practice where nets are scraped along the seabed – could have caused the release of up to 370m tonnes of CO2 between 1996 and 2020, a new study found. As well as being harmful for wildlife living near the bottom of the ocean, bottom-trawling disturbs carbon that was previously locked up for millenia, the researchers said. They used a combination of satellite data tracking fishing events and carbon cycling modelling to examine how bottom-trawling could cause CO2 emissions. The researchers also found that, in heavily trawled seas, the volume of carbon released is likely to be enough to drive ocean acidification – known to be harmful to a range of ocean wildlife, from coral reefs to fish.

Multi-decadal trends of low-clouds at the tropical montane cloud forests

Ecological Indicators

New research suggested that low-cloud cover is declining over tropical montane cloud forests because of climate change, posing an existential threat to these unique mountain ecosystems. The study used climate data to study changes to the proportion of sky covered by cloud cover and other climate variables in 521 tropical montane cloud forests across the world from 1997 to 2020. The researchers found that proportional cloud cover has declined at 70% of these sites, with cloud forests in central and South America and south-east Asia most affected. Decreases in cloud cover were associated with increases in surface temperature and decreases in soil moisture, “revealing that the tropical montane cloud forests’ climate is changing”, the researchers added.

Livestock increasingly drove global agricultural emissions growth from 1910-2015

Environmental Research Letters

Emissions from agriculture in 2015 were more than three times bigger than they were around one century prior, a study found. Scientists developed a dataset of global emissions from the agriculture sector across 10 time periods between 1910 and 2015. They found that agriculture emissions from livestock, soil management and fossil energy inputs “increased continuously” during this time by an overall factor of 3.5, with methane accounting for the majority of these emissions. The study said that reduced emissions intensity, especially for livestock, “partly counterbalanced” the overall rise in emissions to varying degrees. The researchers wrote that the findings “underscore the large potential of reducing livestock production and consumption for mitigating the climate impacts of agriculture”.

In the diary

- 6 February: European Commission to publish 2040 emissions-reduction target recommendations

- 12-17 February: Fourteenth meeting of the Conference of the Parties to the Convention on the Conservation of Migratory Species of Wild Animals | Samarkand, Uzbekistan

- 14 February: Indonesian general election

Cropped is researched and written by Dr Giuliana Viglione, Aruna Chandrasekhar, Daisy Dunne, Orla Dwyer and Yanine Quiroz. Please send tips and feedback to cropped@carbonbrief.org

The post Cropped 31 January 2024: French farmers and the far right; Amazon affairs; EU offsetting ban appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Cropped 31 January 2024: French farmers and the far right; Amazon affairs; EU offsetting ban

Climate Change

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

The country’s largest exporter of liquefied natural gas benefited from what critics say is a questionable IRS interpretation of tax credits.

Cheniere Energy, the largest producer and exporter of U.S. liquefied natural gas, received $370 million from the IRS in the first quarter of 2026, a payout that shipping experts, tax specialists and a U.S. senator say the company never should have received.

Cheniere Energy Received $370 Million IRS Windfall for Using LNG as ‘Alternative’ Fuel

Climate Change

DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Absolute State of the Union

‘DRILL, BABY’: US president Donald Trump “doubled down on his ‘drill, baby, drill’ agenda” in his State of the Union (SOTU) address, said the Los Angeles Times. He “tout[ed] his support of the fossil-fuel industry and renew[ed] his focus on electricity affordability”, reported the Financial Times. Trump also attacked the “green new scam”, noted Carbon Brief’s SOTU tracker.

COAL REPRIEVE: Earlier in the week, the Trump administration had watered down limits on mercury pollution from coal-fired power plants, reported the Financial Times. It remains “unclear” if this will be enough to prevent the decline of coal power, said Bloomberg, in the face of lower-cost gas and renewables. Reuters noted that US coal plants are “ageing”.

OIL STAY: The US Supreme Court agreed to hear arguments brought by the oil industry in a “major lawsuit”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper said the firms are attempting to head off dozens of other lawsuits at state level, relating to their role in global warming.

SHIP-SHILLING: The Trump administration is working to “kill” a global carbon levy on shipping “permanently”, reported Politico, after succeeding in delaying the measure late last year. The Guardian said US “bullying” could be “paying off”, after Panama signalled it was reversing its support for the levy in a proposal submitted to the UN shipping body.

Around the world

- RARE EARTHS: The governments of Brazil and India signed a deal on rare earths, said the Times of India, as well as agreeing to collaborate on renewable energy.

- HEAT ROLLBACK: German homes will be allowed to continue installing gas and oil heating, under watered-down government plans covered by Clean Energy Wire.

- BRAZIL FLOODS: At least 53 people died in floods in the state of Minas Gerais, after some areas saw 170mm of rain in a few hours, reported CNN Brasil.

- ITALY’S ATTACK: Italy is calling for the EU to “suspend” its emissions trading system (ETS) ahead of a review later this year, said Politico.

- COOKSTOVE CREDITS: The first-ever carbon credits under the Paris Agreement have been issued to a cookstove project in Myanmar, said Climate Home News.

- SAUDI SOLAR: Turkey has signed a “major” solar deal that will see Saudi firm ACWA building 2 gigawatts in the country, according to Agence France-Presse.

$467 billion

The profits made by five major oil firms since prices spiked following Russia’s invasion of Ukraine four years ago, according to a report by Global Witness covered by BusinessGreen.

Latest climate research

- Claims about the “fingerprint” of human-caused climate change, made in a recent US Department of Energy report, are “factually incorrect” | AGU Advances

- Large lakes in the Congo Basin are releasing carbon dioxide into the atmosphere from “immense ancient stores” | Nature Geoscience

- Shared Socioeconomic Pathways – scenarios used regularly in climate modelling – underrepresent “narratives explicitly centring on democratic principles such as participation, accountability and justice” | npj Climate Action

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

The constituency of Richard Tice MP, the climate-sceptic deputy leader of Reform UK, is the second-largest recipient of flood defence spending in England, according to new Carbon Brief analysis. Overall, the funding is disproportionately targeted at coastal and urban areas, many of which have Conservative or Liberal Democrat MPs.

Spotlight

Is there really a UK ‘greenlash’?

This week, after a historic Green Party byelection win, Carbon Brief looks at whether there really is a “greenlash” against climate policy in the UK.

Over the past year, the UK’s political consensus on climate change has been shattered.

Yet despite a sharp turn against climate action among right-wing politicians and right-leaning media outlets, UK public support for climate action remains strong.

Prof Federica Genovese, who studies climate politics at the University of Oxford, told Carbon Brief:

“The current ‘war’ on green policy is mostly driven by media and political elites, not by the public.”

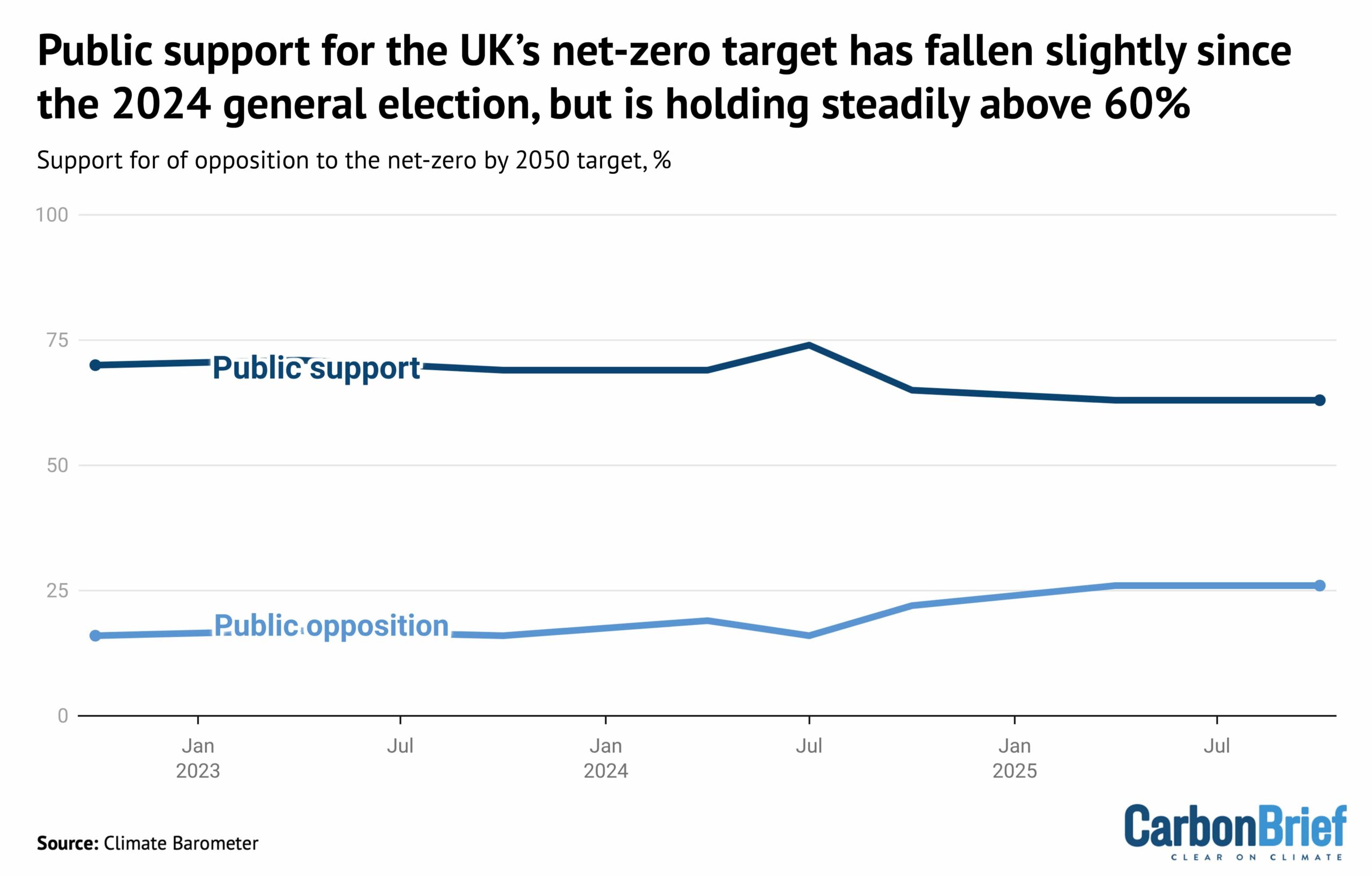

Indeed, there is still a greater than two-to-one majority among the UK public in favour of the country’s legally binding target to reach net-zero emissions by 2050, as shown below.

Steve Akehurst, director of public-opinion research initiative Persuasion UK, also noted the growing divide between the public and “elites”. He told Carbon Brief:

“The biggest movement is, without doubt, in media and elite opinion. There is a bit more polarisation and opposition [to climate action] among voters, but it’s typically no more than 20-25% and mostly confined within core Reform voters.”

Conservative gear shift

For decades, the UK had enjoyed strong, cross-party political support for climate action.

Lord Deben, the Conservative peer and former chair of the Climate Change Committee, told Carbon Brief that the UK’s landmark 2008 Climate Change Act had been born of this cross-party consensus, saying “all parties supported it”.

Since their landslide loss at the 2024 election, however, the Conservatives have turned against the UK’s target of net-zero emissions by 2050, which they legislated for in 2019.

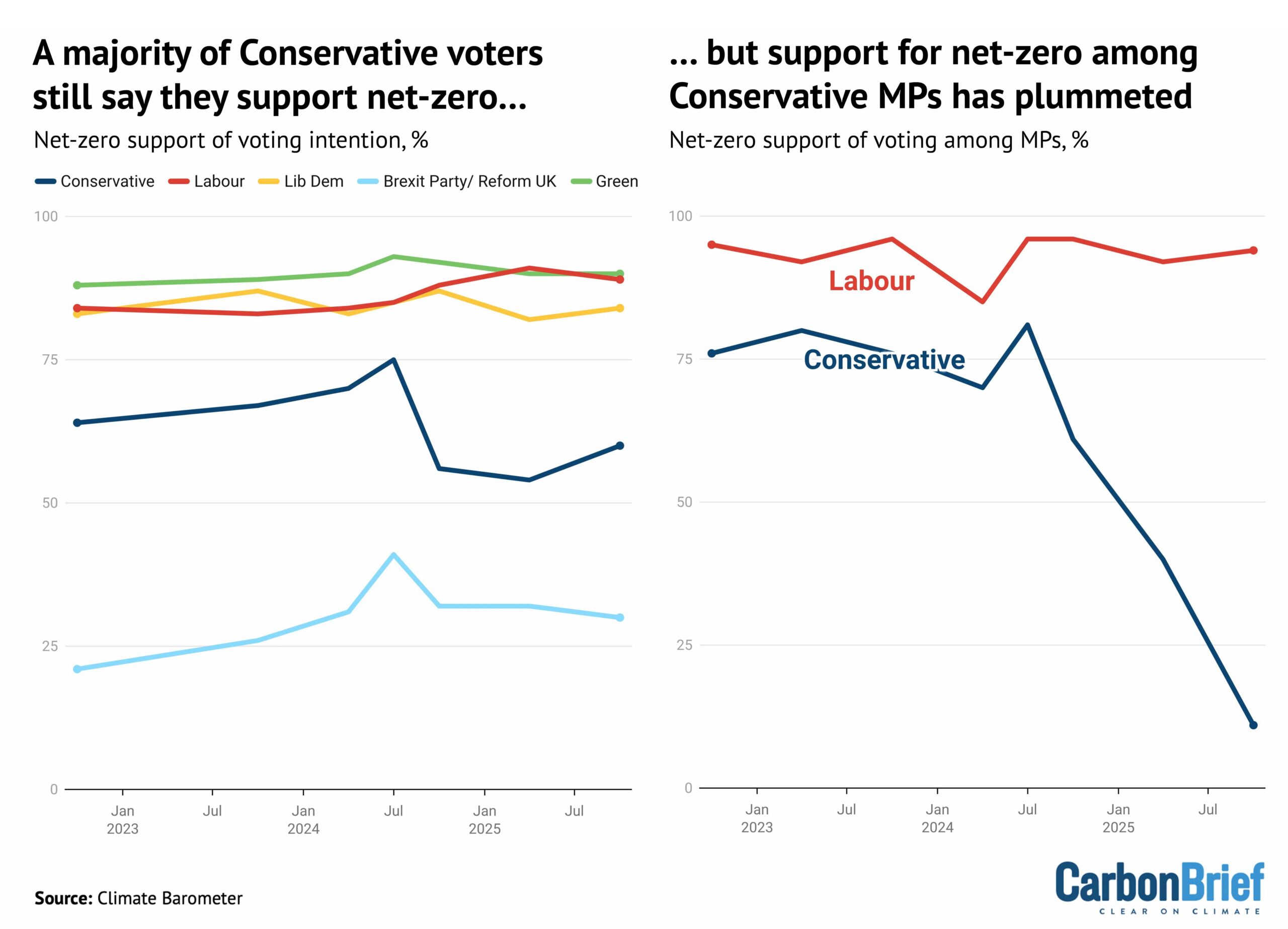

Curiously, while opposition to net-zero has surged among Conservative MPs, there is majority support for the target among those that plan to vote for the party, as shown below.

Dr Adam Corner, advisor to the Climate Barometer initiative that tracks public opinion on climate change, told Carbon Brief that those who currently plan to vote Reform are the only segment who “tend to be more opposed to net-zero goals”. He said:

“Despite the rise in hostile media coverage and the collapse of the political consensus, we find that public support for the net-zero by 2050 target is plateauing – not plummeting.”

Reform, which rejects the scientific evidence on global warming and campaigns against net-zero, has been leading the polls for a year. (However, it was comfortably beaten by the Greens in yesterday’s Gorton and Denton byelection.)

Corner acknowledged that “some of the anti-net zero noise…[is] showing up in our data”, adding:

“We see rising concerns about the near-term costs of policies and an uptick in people [falsely] attributing high energy bills to climate initiatives.”

But Akehurst said that, rather than a big fall in public support, there had been a drop in the “salience” of climate action:

“So many other issues [are] competing for their attention.”

UK newspapers published more editorials opposing climate action than supporting it for the first time on record in 2025, according to Carbon Brief analysis.

Global ‘greenlash’?

All of this sits against a challenging global backdrop, in which US president Donald Trump has been repeating climate-sceptic talking points and rolling back related policy.

At the same time, prominent figures have been calling for a change in climate strategy, sold variously as a “reset”, a “pivot”, as “realism”, or as “pragmatism”.

Genovese said that “far-right leaders have succeeded in the past 10 years in capturing net-zero as a poster child of things they are ‘fighting against’”.

She added that “much of this is fodder for conservative media and this whole ecosystem is essentially driving what we call the ‘greenlash’”.

Corner said the “disconnect” between elite views and the wider public “can create problems” – for example, “MPs consistently underestimate support for renewables”. He added:

“There is clearly a risk that the public starts to disengage too, if not enough positive voices are countering the negative ones.”

Watch, read, listen

TRUMP’S ‘PETROSTATE’: The US is becoming a “petrostate” that will be “sicker and poorer”, wrote Financial Times associate editor Rana Forohaar.

RHETORIC VS REALITY: Despite a “political mood [that] has darkened”, there is “more green stuff being installed than ever”, said New York Times columnist David Wallace-Wells.

CHINA’S ‘REVOLUTION’: The BBC’s Climate Question podcast reported from China on the “green energy revolution” taking place in the country.

Coming up

- 2-6 March: UN Food and Agriculture Organization regional conference for Latin America and Caribbean, Brasília

- 3 March: UK spring statement

- 4-11 March: China’s “two sessions”

- 5 March: Nepal elections

Pick of the jobs

- The Guardian, senior reporter, climate justice | Salary: $123,000-$135,000. Location: New York or Washington DC

- China-Global South Project, non-resident fellow, climate change | Salary: Up to $1,000 a month. Location: Remote

- University of East Anglia, PhD in mobilising community-based climate action through co-designed sports and wellbeing interventions | Salary: Stipend (unknown amount). Location: Norwich, UK

- TABLE and the University of São Paulo, Brazil, postdoctoral researcher in food system narratives | Salary: Unknown. Location: Pirassununga, Brazil

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 27 February 2026: Trump’s fossil-fuel talk | Modi-Lula rare-earth pact | Is there a UK ‘greenlash’? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

Seven Pacific island nations say they will demand heftier levies on global shipping emissions if opponents of a green deal for the industry succeed in reopening negotiations on the stalled accord.

The United States and Saudi Arabia persuaded countries not to grant final approval to the International Maritime Organization’s Net-Zero Framework (NZF) in October and they are now leading a drive for changes to the deal.

In a joint submission seen by Climate Home News, the seven climate-vulnerable Pacific countries said the framework was already a “fragile compromise”, and vowed to push for a universal levy on all ship emissions, as well as higher fees . The deal currently stipulates that fees will be charged when a vessel’s emissions exceed a certain level.

“For many countries, the NZF represents the absolute limit of what they can accept,” said the unpublished submission by Fiji, Kiribati, Vanuatu, Nauru, Palau, Tuvalu and the Solomon Islands.

The countries said a universal levy and higher charges on shipping would raise more funds to enable a “just and equitable transition leaving no country behind”. They added, however, that “despite its many shortcomings”, the framework should be adopted later this year.

US allies want exemption for ‘transition fuels’

The previous attempt to adopt the framework failed after governments narrowly voted to postpone it by a year. Ahead of the vote, the US threatened governments and their officials with sanctions, tariffs and visa restrictions – and President Donald Trump called the framework a “Green New Scam Tax on Shipping”.

Since then, Liberia – an African nation with a major low-tax shipping registry headquartered in the US state of Virginia – has proposed a new measure under which, rather than staying fixed under the NZF, ships’ emissions intensity targets change depending on “demonstrated uptake” of both “low-carbon and zero-carbon fuels”.

The proposal places stringent conditions on what fuels are taken into consideration when setting these targets, stressing that the low- and zero-carbon fuels should be “scalable”, not cost more than 15% more than standard marine fuels and should be available at “sufficient ports worldwide”.

This proposal would not “penalise transitional fuels” like natural gas and biofuels, they said. In the last decade, the US has built a host of large liquefied natural gas (LNG) export terminals, which the Trump administration is lobbying other countries to purchase from.

The draft motion, seen by Climate Home News, was co-sponsored by US ally Argentina and also by Panama, a shipping hub whose canal the US has threatened to annex. Both countries voted with the US to postpone the last vote on adopting the framework.

The IMO’s Panamanian head Arsenio Dominguez told reporters in January that changes to the framework were now possible.

“It is clear from what happened last year that we need to look into the concerns that have been expressed [and] … make sure that they are somehow addressed within the framework,” he said.

Patchwork of levies

While the European Union pushed firmly for the framework’s adoption, two of its shipping-reliant member states – Greece and Cyprus – abstained in October’s vote.

After a meeting between the Greek shipping minister and Saudi Arabia’s energy minister in January, Greece said a “common position” united Greece, Saudi Arabia and the US on the framework.

If the NZF or a similar instrument is not adopted, the IMO has warned that there will be a patchwork of differing regional levies on pollution – like the EU’s emissions trading system for ships visiting its ports – which will be complicated and expensive to comply with.

This would mean that only countries with their own levies and with lots of ships visiting their ports would raise funds, making it harder for other nations to fund green investments in their ports, seafarers and shipping companies. In contrast, under the NZF, revenues would be disbursed by the IMO to all nations based on set criteria.

Anais Rios, shipping policy officer from green campaign group Seas At Risk, told Climate Home News the proposal by the Pacific nations for a levy on all shipping emissions – not just those above a certain threshold – was “the most credible way to meet the IMO’s climate goals”.

“With geopolitics reframing climate policy, asking the IMO to reopen the discussion on the universal levy is the only way to decarbonise shipping whilst bringing revenue to manage impacts fairly,” Rios said.

“It is […] far stronger than the Net-Zero Framework that is currently on offer.”

The post Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen appeared first on Climate Home News.

Pacific nations want higher emissions charges if shipping talks reopen

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits