In the midst of a record-breaking heatwave in Europe, the UK city of Exeter recently played host to the second international conference on “tipping points”.

The event was billed as a “call to action” to the “research community, policymakers and business to raise awareness and understanding of the importance of tipping points and to accelerate the required action”.

As human activity drives global temperatures to record highs, multiple parts of the Earth system are at risk of being pushed beyond thresholds that would see them shift irreversibly into a new state.

The conference also focused heavily on “positive tipping points”, where large-scale, self-propelling social change can reduce the impact of humans on the climate.

Hosted jointly by the Global Systems Institute at the University of Exeter, the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research and the Max Planck Institute of Geoanthropology, the conference was the second event dedicated to global tipping points, following the first in 2022.

A statement issued by conference convenors – and endorsed by hundreds of delegates – warned that the window for preventing tipping points is “rapidly closing”.

It called for “immediate, unprecedented action from policymakers worldwide and especially from leaders” at the forthcoming COP30 climate talks in Brazil.

The meeting was part of a week-long Exeter Climate Forum, which also included a separate Climate Conference and a series of community and business-focused events.

In this article, Carbon Brief draws together some of the key talking points, new research and ideas that emerged from the four-day event.

Climate tipping points

As he opened the conference, Prof Tim Lenton – director of the University of Exeter’s Global Systems Institute and one of three convenors of the event – introduced tipping points and set out the direction of the upcoming four days of talks.

He explained that tipping points are caused by “amplifying feedbacks” in a system becoming “self propelling”. He said these systems are “very hard to reverse and it could be quite abrupt”.

Lenton warned that since the last tipping points conference in 2022, global temperatures have risen, bringing many Earth system tipping points closer.

However, he told the conference that not all tipping points are harmful, distinguishing between a “bad tipping point in the climate or a positive one in societies and technologies”.

Lenton told the conference that “there is a compelling case that we could accelerate out of trouble”, adding that we could “lift [many people] out of harm” by focusing on positive tipping points.

Prof Johan Rockström, director of the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research (PIK) and joint convenor of the conference, talked about the importance of considering planetary boundaries in tipping-points research. This framework sets out nine interlinked thresholds that would ensure a “safe operating space for humanity”.

Rockström told the conference that using this “whole Earth approach” can highlight that thresholds for tipping points may be lower than when only considering climate change.

For example, he said the Amazon rainforest is at risk of crossing a tipping point that could trigger “dieback” at around 3-5C of global warming above pre-industrial levels. However, he said that “transgressing” other thresholds, such as deforestation and moisture levels, could cause the system to tip sooner.

Rockström also argued that Earth system risks have now reached the “global catastrophic” level – defined by the Global Challenges Foundation as an event or process that “would kill or seriously harm more than 10% of the human population”.

He said the collapse of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, the dieback of the Amazon rainforest and the shutdown of the Atlantic Meridional Overturning Circulation (AMOC) present the greatest risk, as they have a high severity of impact and probability of occurrence.

He closed by arguing that scientists need to better communicate the risks of tipping points to encourage more action.

Prof Ricarda Winkelmann, the third convenor of the conference and professor of climate system analysis at PIK, discussed tipping of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, which together hold enough ice to raise global sea levels by 65 metres.

Winkelmann encouraged the delegates to consider timescales. She described tipping of the ice sheets as “slow-onset systems”, but highlighted that they can also “undergo quick and abrupt changes”.

To demonstrate this, she played a video of “calving” from the Ilulissat glacier in western Greenland. This was the largest calving ever caught on camera, which saw chunks of ice up to 1,000-metres thick break off the main ice sheet, she said.

Winkelmann described a “time clash” between the long-term changes in biophysical systems and short-term changes in socioeconomic systems. She concluded:

“The choices and actions implemented in this decade really have impacts now and also for the next 1,000 years.”

Also in the opening plenary session, Dr Carlos Nobre, a former Earth system scientist at the University of São Paulo, discussed tipping in the Amazon rainforest.

He said that decades of “high-level deforestation and degradation” across the Amazon have resulted in “much less water recycling”, as well as droughts and forest fires, that are creating a “tremendous health problem” for people.

Nobre noted that higher levels of deforestation push down the temperature threshold at which the rainforest could tip from lush rainforest to dry savannah.

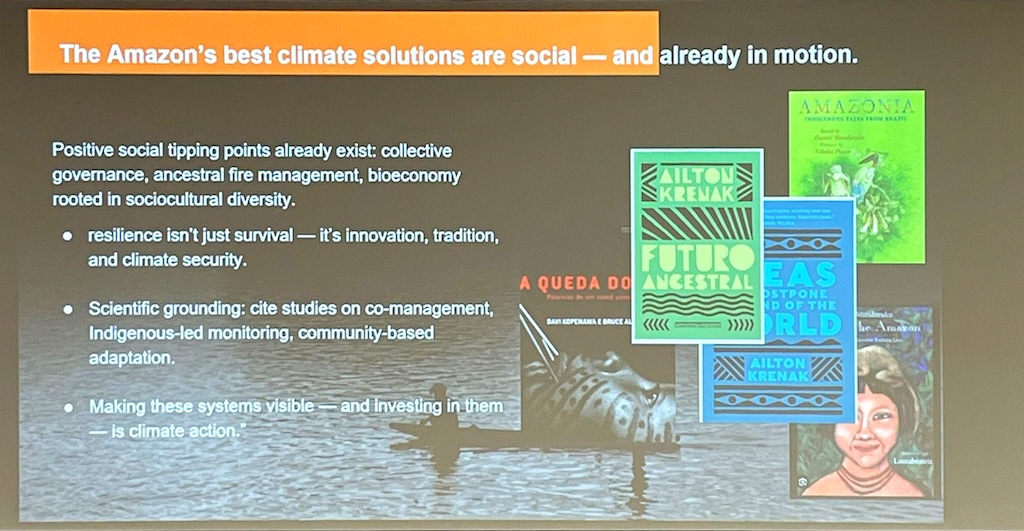

He also discussed “nature-based solutions” and the importance of combining scientific knowledge with Indigenous knowledge and local communities.

Dr David Obura, the founding director of CORDIO East Africa and chair of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), highlighted the importance of the IPBES framing, which emphasises the need to connect nature and people.

He flagged the state of the world’s coral reefs, telling delegates that, as of the end of last year, 44% of the 800 coral reef species studied by the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) are “threatened”.

Obura added that “ocean temperatures have shot up in the last few years”. However, he warned that looking at temperature alone is insufficient, arguing that there are other physical and socioeconomic factors that need to be understood.

In the panel discussion that followed, Nobre stressed the importance of the COP30 talks in Brazil this year “looking at solutions” to the changing climate. Obura said that humanity has “extracted wealth from nature into economic systems”, arguing that this money must “come back into nature”.

When asked why the risk of tipping points is not being discussed at the UN security council, Rockström flagged an “inability to handle timescales” and said that language around uncertainty allows politicians to “kick the can down the road”.

When asked about the media, Rockström said it is “unfortunate” that humanity is allowing a media landscape that “underplays risk” and allows only “soundbites” from scientists. He added that the “media has a huge responsibility” in the current framing of climate change.

However, Winkelmann said the media “can play an incredibly important role in moving things forward”.

Broader focus

While the central themes of the 2022 conference were the two main areas of climate tipping points and positive tipping points, the 2025 event took a broader focus that encompassed social systems and governance.

Prof Winkelmann told Carbon Brief that this reflected how the tipping points “community” is much larger now than it was three years ago:

“The community has grown a lot since [2022] and it especially also includes not just the scientific community, both on the biophysical side and the social side, but also a lot of people from policy, governance and business. So I think it is really brilliant to have this community here together, thinking about tipping dynamics and the impacts in this holistic approach.”

Lenton told Carbon Brief the conference was “bigger and more diverse” than the 2022 edition. This, he said, was likely due to “demand for knowledge of the subject”, alongside a wider range of “stakeholders, voices and actors” being engaged in discussions about tipping points.

While tipping points are well-defined in natural sciences, they are less so in the social sciences, Rockström told Carbon Brief:

“I would even argue that many social scientists – even some social scientists at this conference – are even uncomfortable in using the term social tipping point, or positive tipping point, and are much more academically grounded in defining ‘social transformations’, ‘social transitions’ or ‘social change’. I have a strong respect for that. It is really important to humbly recognise that the social sciences come at this with very different methods and theories.”

In a plenary session on social-ecological tipping points, Dr Patricia Pinho – deputy science director at the Amazon Environmental Research Institute (IPAM) – argued that “we can’t really model forest resilience if we ignore the people that are on the frontline”.

According to her presentation, “Indigenous and traditional communities are already experiencing and resisting socio-ecological tipping points”.

Global warming and land-use change have led to forest degradation in 36% of the region, Pinho said. Combined with increasing forest fires, heat and drought, communities are seeing impacts on “food security, health [and] loss of biodiversity”, she added:

“So what we are seeing is loss of identity, place, attachment. People are losing their relationship [with the Amazon] and livelihoods and culture.”

Another plenary considered the positive tipping points in “socio-technical systems”.

Among the talks, Simon Sharpe, former deputy director of the UK government’s COP26 unit and now managing director of the non-profit research group S-Curve Economics, outlined the progress towards positive tipping points in the sectors of power generation, road transport and steel production.

While the power-sector transition is “going quite well” and light road transport is already seeing electric vehicles (EVs) make up “20% of new car sales globally”, the steel transition is in its “very early stages”, Sharpe explained.

For the steel industry, the “tipping point that we have to cross is in terms of risk perception”, Sharpe said:

“You have to get to the point where industry feels that actually it’s no longer the ‘first-mover risk’ that is the biggest risk – it’s the ‘late-mover risk’ that’s the biggest risk.”

Sharpe argued that this was best achieved by a clean-steel subsidy, noting that “we’ve seen for the brief period where the US had its [Inflation Reduction Act] and was strongly subsidising clean industrial production”. He continued:

“That resulted in a big shift of industry lobbying in Japan and the EU, where all the steel companies suddenly said, ‘Oh, can we have clean-steel subsidies as well, please?’”

Focusing specifically on EVs, Dr Jean-Francois Mercure from the University of Exeter described his forthcoming study on the tipping point “that is unfolding now”.

This has been driven by a feedback loop between the falling cost of EVs and the rise in how many are being purchased, Mercure explained:

“The cost coming down helps people buy more electric vehicles; more electric vehicles [being bought] causes the cost to come down.”

While there is “exponential growth” in EV sales, Mercure showed how the sales market share in conventional cars has been “plunging” in “Germany, UK, France and especially China” since 2019:

“So we’re kind of saying, yes, the system has started to tip into this new electric vehicle regime.”

However, Mercure added, “it’s fragile” as it could be bogged down by policy reversals. He also noted that there are barriers, such as China’s dominance in producing batteries, which is “becoming problematic” and led to tariffs in the EU and US.

From the audience, Prof Joyeeta Gupta of the University of Amsterdam questioned whether EVs are seeing a “long-term” tipping point when the global south is considered:

“Electric cars are going up the global north, but the old petrol cars are going south. Basically, what you’re seeing is that when certain things improve in the global north, the older stuff just gets dumped on the global south.”

Governance

The conference also emphasised the importance of governance, with multiple breakout sessions and a plenary dedicated to the topic.

In one breakout session, author Herb Simmens explained that governance is a “system of rules, processes and practices by which public institutions are managed and controlled”, which aim to “establish how decisions are to be made, and then to ensure that those responsible for making them do so”.

He argued that setting out to limit tipping points should be considered policymaking, not governance. However, he said that strong global governance is needed in order to oversee the implementation of policies to stop global warming. He also added that local governance is needed in many instances – for example, to stop deforestation in the Amazon in order to prevent the rainforest from tipping.

Dr Manjana Milkoreit – a postdoctoral researcher at the University of Oslo – chaired a plenary session on governance. She told delegates that the 2023 tipping points report identifies “two major domains of governance involved” in managing global tipping points. These are “prevention” and “reorganisation”, she said.

Sandrine Dixson-Decleve, co-president of the not-for-profit Club of Rome, stressed the importance of discussing how to “integrate planetary emergency at the top level into constitutional law”. She concluded:

“If we can’t get the governance to work right now, we have to think about other types of governance frameworks at the local level, community level, that start to create the feedback loop all the way back up to the international level.”

Durwood Zaelke, founder and president of the Institute for Governance & Sustainable Development, highlighted the success of the Montreal Protocol – an agreement signed in 1987 by nearly 200 countries to limit emissions of “ozone-depleting substances” in an effort to stem the damage to the ozone layer.

He argued that governance on cutting emissions must be binding, as the Montreal Protocol was, rather than voluntary.

He also argued that cutting CO2 emissions is “essential, but a slow process” and advocated for more emphasis on cutting emissions of “short-lived super-pollutants”.

Prof Per Olsson, deputy science director at the Stockholm Resilience Centre, said there has been a “deeply problematic” backlash in the past five years, in the form of “political polarisation”, “war”, “democratic backsliding” and the “dehumanisation of people that think differently from you”. He warned that these “threaten to derail many processes”.

Oliver Morton is a senior editor at the Economist and serves on the board of trustees of the Degrees Initiative – a non-government organisation that focuses on promoting expertise on solar radiation management in the global south. (However, he said at the start of his talk that he was not speaking in these capacities.)

Morton argued for a greater emphasis on solar geoengineering in the tipping points community.

Morton told delegates that the lengthy 2023 global tipping points report featured only a few paragraphs on solar geoengineering, stating that the technology “might” help limit temperature rise, he said:

“I would really be interested in that ‘might’. But that’s not, in fact, what this community does. It’s not what people particularly seem to want to talk about.”

Morton noted that many delegates of the recent Arctic Repair Conference, which was held in Cambridge in June, were present at the tipping points conference, highlighting the “overlap” between the two fields.

He recognised the challenges with the governance of solar geoengineering, but added that there are challenges “for all governance”. He also emphasised that “everyone in the solar geoengineering community” says that the technology would “complement, not replace, mitigation”.

Morton emphasised the need for expertise on solar geoengineering in the global south. He concluded that “sidelining” research on geoengineering, which potentially could reduce harm, opens up the tipping-points community to criticism for not considering all options. He referred to this as “choice-editing”.

Finally, Prof Joyeeta Gupta, spoke about the divide between the global north and global south.

She said that she is working to introduce a global constitution “to try to understand how to regulate the public and private sector” and she invited the audience to participate by sending in submissions.

When asked whether the phrase “tipping points” has been watered down, Sandrine said that words like “regenerative” and “sustainable development” are overused and agreed that we “can’t keep playing with the language until it becomes nonsensical”. She called on conference delegates to come together to define key terms.

At a breakout session, Prof Karen Morrow, a professor of environmental law at Swansea University, explained that the legal system currently does not deal well with any issue at the planetary scale, as global problems cannot be reduced to a “nice, tidy jurisdictional issue”.

She said that the irreversibility of Earth system tipping points is “horriffic”. However, she noted that the language of uncertainty in science can make it hard to “find a foothold” legally, arguing that the irreversibility may help with this by providing more certainty.

She added that there are currently laws around “obligation to prevent harm”, but said that there are “not enough”, arguing that we need laws that dictate a “substantive restraint on human activities”.

Positive tipping points

A significant portion of the conference was dedicated to “positive tipping points” – described to Carbon Brief by Rockström as “social transformations” that generate “feedbacks that are self-enforcing”, making them difficult to reverse.

Examples of these social transformations that featured in plenaries and research sessions included the rapid rollout of EVs in Norway, tree-planting schemes in Uganda, investments in “regenerative” cotton farming and the falling costs and rising adoption of solar energy around the world.

In a breakout session, Dr Jean-Francois Mercure said the “positive tipping point narrative is good because it changes the policy narrative”. He explained:

“We used to have this narrative, which goes – ‘we tax [and] we price the externality because prices need to reflect costs’. This is demanding because it is politically difficult to tax and subsidies need to be justified. [That narrative says] we are pushing a thing that gets harder the more we do it – so there is a limit to climate action.

“This is not how it really works. When you look at the solar revolution, we had to push up to a certain point, after which it went off on its own. Electric vehicles, too. This [narrative] changes what policymakers need to do and think. They need to work to push over the initial hurdle.”

In a plenary session, Kate Raworth, an ecological economist at the University of Oxford, highlighted how a growing number of states, cities and regions around the world had adopted her “doughnut” theory of economics.

“Doughnut economics” is a framework which imagines a global economy which prioritises meeting the needs of people without overshooting planetary boundaries.

Raworth highlighted how more than 50 municipal governments had publicly adopted the framework since 2019 – and added there are “another 50 doing it behind the scenes”. She said that “peer-to-peer inspiration” has been a powerful force in driving momentum behind the framework’s popularity.

Jameela Mahmood, executive director of the Sunway Centre for Planetary Health at Sunway University in Kuala Lumpur, described how her organisation’s advocacy had led to the Malaysian government’s adoption of a planetary health framework in its forthcoming economic development plan. She also said planetary health would become a mandatory part of the nation’s undergraduate curriculum from 2026.

Túlio Andrare, chief strategy and alignment officer for the COP30 presidency, described the Brazilian government’s plans to convene a “global mutirão”, which encourages individuals, communities and organisations to make self-determined commitments to take actions to tackle climate change. (Mutirão is a word from the Indigenous Tupi-Guarani language family that refers to collective action). He said:

“The global mutirão is about inviting people to think about who they are and what they can offer. It is also about designing potential positive tipping points. Because if we have different initiatives that are self-organised, we can integrate those local initiatives in a global framework.”

In a separate plenary session on tipping points within food systems, Rune Baastrup, director of development at Democracy X, a private foundation focused on deliberate democracy, presented on a project to shift eating habits in Denmark.

The project, which he said is grounded in “sociological literature”, is to encourage a push towards plant-based eating from a local level, by funding and coordinating communal meals that citizens arrange for and with each other. Baastrup explained:

“It’s not about politicians going out pointing fingers at citizens. It is about citizens engaging and then mobilising each other – not necessarily because they want to save the world, but because they want to do interesting and cool things with their neighbours.”

According to Democracy X’s theory of change, reaching “one in 10 Danes” through this work would be enough to galvanise a “profoundly more deep green transition” in the Scandinavian country, Baastrup said.

In the same session, journalist and author George Monbiot said it was “questionable” whether the global food system could achieve a “positive tipping point”.

However, he said there were a number of actions that could be taken to create a food system which maintains high yields, reduces environmental impacts while remaining diversified and leaving space for nature restoration and recovery. He argued that these included: switching away from an animal-based diet to a plant-based diet; the embrace of perennial grain and arable crops; and production of food outside the farming system, including through precision fermentation.

Monbiot said the conversation around food systems was “going backwards”, pointing to the growing popularity of “simple living, grow-your-own soul food” tropes on social media:

“There is this complete confusion between what looks nice – between the bucolic, romantic, aesthetic and cottagecore that you can post up on Instagram – and what we actually need in order to intervene effectively in this huge Leviathan of a system which is going to crush us into dust.”

In his closing remarks, Lenton mused that the research community was on a quest to discover the “recipe” behind positive tipping points. He explained:

“We’re passionate as researchers to seek out the early opportunity signals that systems we want to get rid of might be able to get tipped out of.”

Having a toolkit for identifying the “generic” signals of when an incumbent system is showing signs of destabilising could guide efforts from activists, policymakers and investors to drive positive change for the planet, he said.

Lenton said upcoming research, set to be published in Sustainability Science, represented a “first attempt” at a methodology “for anyone who wants to ask whether a system has the potential for a positive tipping”. The methodology in question would also seek to answer the following questions, he said:

“If [a system] has [the potential to tip], how close is it? What factors would influence it? In particular, what could bring it forward? And then what actions could influence those factors to tip other systems?”

Lenton urged scientists at the conference to help him “refine and apply” the methodology. He also urged colleagues to keep “documenting” evidence of positive tipping over the years ahead. He explained:

“There is a theory of change here. We have got to enable each other to learn faster [and] to spread these initiatives better.”

New science

Modelling projects

Along with the main plenaries, the conference included around 50 breakout meetings, split between “research sessions” and “action workshops”.

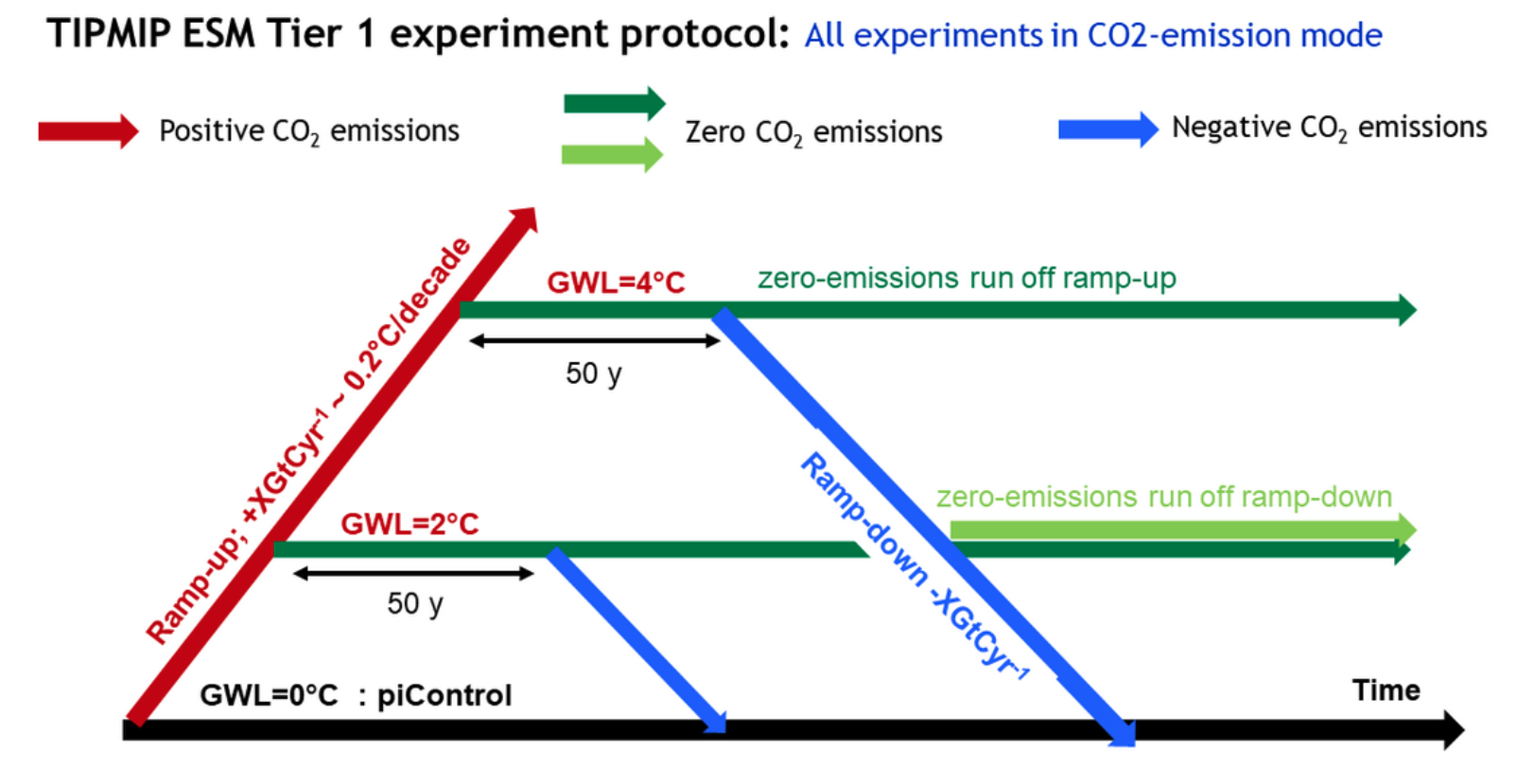

Among the new research being presented at these sessions were early results from the “TIPMIP” international modelling project.

Rockström told Carbon Brief the “biggest change” in tipping-points science since the first conference in 2022 is the launch of TIPMIP. He said:

“The most solid scientific basis in the IPCC are all the ‘MIPs’, the modelling comparison programmes. The biggest one is CMIP [the Coupled Model Intercomparison Project], which gives us the data and the scenarios to be able to deliver the Paris Agreement.

“Now, we finally have a MIP for tipping points – and the tipping point comparison community is here at the conference, as well as [scientists from] the big Earth system models. Big tipping modelling analysis [is underway] on AMOC risks, on the Amazon rainforest, on permafrost and the ice sheets. That is a major advancement.”

Dr Jeremy Walton, who leads the software engineering team for the UK Earth System Model at the Met Office Hadley Centre, kicked off one research session by unpacking the Earth system modelling “experiment protocol” within TIPMIP. This is a “framework for the modelling and investigation of climate overshoot and tipping points”, he explained, which sets out a consistent set of “idealised” – or simplified – experiments for scientists to conduct in order to build up a large dataset of results from lots of climate models.

The figure below illustrates these experiments, which include control runs with no global warming (black line), runs where warming is stabilised, such as at 2C or 4C (green lines) and further runs where warming is subsequently reduced via carbon removal (blue lines).

In all cases, warming first “ramps up” at a rate of 0.2C per decade “because that matches the observed rate in recent years”, Walton said.

Antarctica

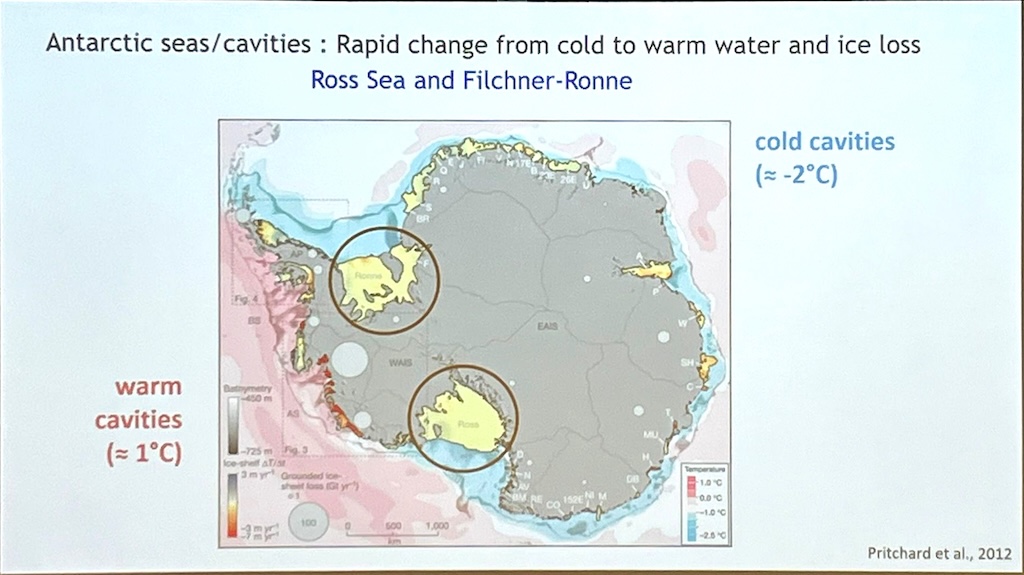

Prof Colin Jones from the University of Leeds presented some initial results from the idealised experiments for the Antarctic ice sheet, carried out by Dr Sophy Oliver of the National Oceanography Centre in Southampton.

The analysis focuses on the massive Ross and Filchner-Ronne ice shelves, which float on the ocean and hold back land ice behind them. At the moment, Jones explained, they are both “cold-water cavities”, in that the ocean water beneath the shelves is “below the freezing point of sea ice”. However, if they “tip” to “switch to being warm-water cavities, then there’s a risk for rapid loss of ice”, he said.

The switch happens because melting of Antarctic ice adds freshwater beneath the ice shelves. This reduces the “density barrier” between the cavity and warmer open ocean, said Jones, reaching a “sudden point where the salinity is sufficiently low that the density has changed and it allows open ocean water” to get into under the ice shelves.

Their model runs suggest that there is a “danger zone” for the Ross ice shelf of around 3.5-4C, Jones said:

“If you go more than 4C, it will always tip [in model runs]…If you stay below about 3C, it will never tip.”

For the Filchner-Ronne ice shelf, “it is basically the same mechanism, but it happens at a higher warming level”, noted Jones, with a “danger zone” around 5-5.5C.

Also focusing on Antarctica, Sacha Sinet from Utrecht University presented analysis on the interactions between AMOC and the polar ice sheets, with results suggesting that the loss of the Antarctic ice sheet could actually stabilise the AMOC and prevent it from collapsing.

Sinet’s research is currently being reviewed before potential publication.

Another study on Antarctica was published on the opening day of the tipping points conference. The research, led by Dr Alessadro Silvano from the National Oceanography Centre, uses satellite data to reveal a marked increase in surface salinity across the Southern Ocean since 2015, coinciding with a “dramatic decline” in Antarctic sea ice.

The findings suggest that the Southern Ocean “might have entered a new system”, Silvano said. He explained how he has been observing an increase in salinity in the top 100 metres of the ocean. This is “counterintuitive”, he said, as “you think the more melting of ice, then you should freshen the ocean instead”.

The increase is because the ocean is becoming “less stratified”, meaning that warm water – which is also more salty – is “able to reach the surface of the ocean more”, making is harder for sea ice to regrow. he explained:

“And this is circumpolar. So it’s happening everywhere you see the increase in salinity.”

This has the potential to drive a self-reinforcing feedback loop, Silvano wrote in an article for the Conversation:

“We may have passed a tipping point and entered a new state defined by persistent sea ice decline, sustained by a newly discovered feedback loop.”

When asked by an audience member whether solar geoengineering could help, Silvano noted: “The problem for Antarctica is that melting is driven by the ocean. You cannot stop warming in the ocean, so that, to me, is an impossible task.”

Ecological shifts

Away from Antarctica, Dr Bette Otto-Bliesner of the US National Center for Atmospheric Research introduced another “MIP” – the What If Modeling Intercomparison Project (WhatIfMIP), which aims to investigate the consequences of what happens if a tipping point is crossed.

In particular, the programme will look at the cascading effects of one tipping element on another, including Amazon dieback, shifts in boreal forests, AMOC collapse, permafrost loss and the collapse of the Greenland and West Antarctic ice sheets, Otto-Bliesner explained.

One area of focus will be on the potential implications of “Sahel greening”, Otto-Bliesner said:

“We don’t think the Sahara is going to green in the next few centuries. But there is a project in the Sahel region called the Great Green Wall Initiative, where they’re actually planting trees. They’ve already started this…So what are the consequences of that, in terms of precipitation, drought, but also…heatwaves?”

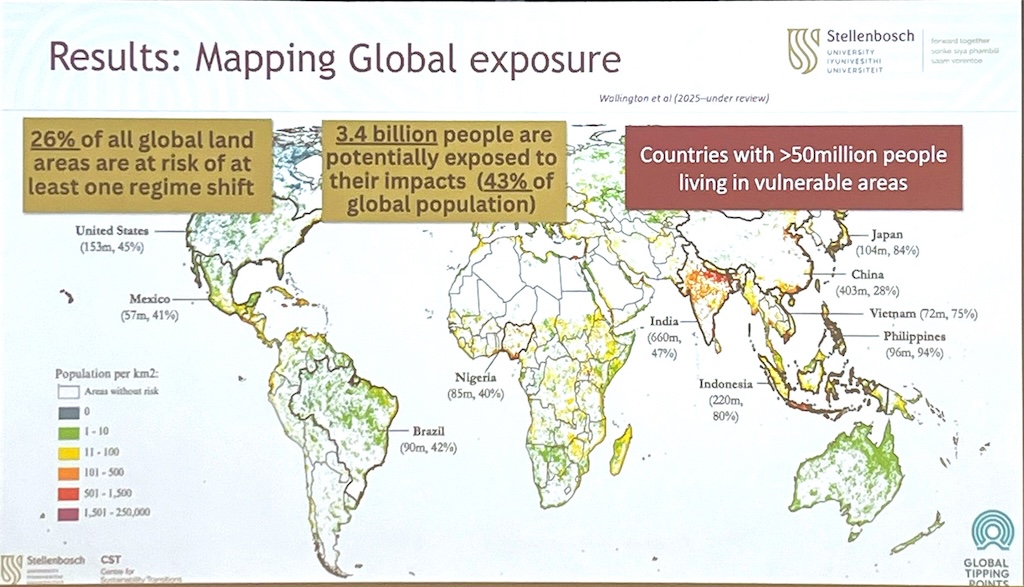

In another talk, Caroline Wallington – from the Centre for Sustainability Transitions at Stellenbosch University in South Africa – presented a global analysis of ecosystems and people at risk of 21 different ecological “regime shifts”.

The findings show that 26% of the global land area is at risk of at least one ecological shift, covering 3.4 billion people, or 43% of the global population.

Around 31% of corals are at risk of a regime shift, Wallington said, while 30% of tundra is at risk from a transition to boreal forest and 28% of tropical forests are at risk of tipping into savannah.

The regions of the world at highest risk include the south Pacific, south-east Asia and central America, Wallington noted. Some of the most populous countries in the world are at risk from these regime shifts, she added, including China, India, the US and Indonesia.

Paris limits

Dr Nico Wunderling, from the Center for Critical Computational Studies at Goethe University Frankfurt and the Potsdam Institute for Climate Impact Research, presented on how tipping point risks are affected by “overshooting” temperature goals, such as the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C limit.

His work indicates that “tipping risks are even non-negligible now at global warming levels of 1.3-1.5C”, while overshooting 2C would mean “entering a very high risk zone for climate tipping elements”.

Wunderling presented some early results – currently undergoing peer review – on how the risk of Amazon dieback depends on both the levels of warming and deforestation.

When only warming is considered, current pathways to 2.7-2.8C above pre-industrial levels “seem to still relatively keep the Amazon rainforest at a safe level”, he said. However, he added, when deforestation is included, tipping risks become much closer – “to levels that are well within the Paris Agreement, so about 1.5-2C”.

Wunderling recently wrote a Carbon Brief guest post on “cascading” tipping points, indicating that the “majority of interactions between tipping elements will lead to further destabilisation of the climate system”.

Where next?

In the closing plenary, Rockström confirmed that PIK would host a tipping points conference in Berlin in 2027.

He also revealed that plans were afoot to host a tipping points conference in 2026 in Malaysia, following discussions with Jameela Mahmood of the Sunway Centre for Planetary Health in Kuala Lumpur.

Rockström said this reflected the need to host the conference in the global south and the importance of “building momentum” around tipping point risks and opportunities.

He added that the Malaysia-hosted conference could be held “in connection” with the COP31 climate summit, should Australia’s bid to host the UN talks in 2026 prove successful.

Meanwhile, a second global tipping points report is earmarked for the latter half of 2025.

(Carbon Brief covered the first global tipping point report in 2023).

Lenton told Carbon Brief the upcoming report will be “tighter” than its predecessor and “major” on governance issues.

Explaining the rationale for giving governance top billing in the report, Lenton said:

“We want to lead on the things we need. We clearly need some improvements in governance and institutions to get on top of both the tipping point risks and, arguably, the opportunities. Everyone can see that – it has been repeated several times already at this meeting. So, it is important to be clear what differences [governance] makes and what different kinds of governance we are calling for.”

The report will also offer an “update on tipping point risks and opportunities”, Lenton said, and include three case studies looking at Earth system tipping points – the shutdown of AMOC, Amazon dieback and coral die-off. It will also feature one “localised” example of a glacier tipping point and its consequences.

The case studies are designed to provide “more specific and concrete guidance” on how to avoid tipping risks, according to Lenton.

In addition, Ricarda Winkelmann told Carbon Brief that she and her colleagues will be answering a “call on the scientific community to put together a robust risk assessment on tipping dynamics”. This will involve “creating a first global atlas of tipping financial risks”, she explained – in time to feed into the seventh assessment report (AR7) of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC).

Discussing AR7 with Carbon Brief, Rockström said he was “very disappointed” that, at a meeting last year, countries decided not to include a special report on tipping points in the IPCC’s AR7 cycle.

This happened because the topic “makes policymakers and some member countries around the world very uncomfortable”, Rockström said.

Despite the “illogical” decision, the AR7 assessment reports will “see much more tipping-point science”, added Rockström, “for the simple reason that we have TIPMIP [and] we have a much broader community now – it’s entering the mainstream of Earth system modelling”.

This is “so important” in order to narrow uncertainty ranges in projections of tipping points, Rockström argued:

“I am of the view that one reason why we’re not acting faster on the climate crisis – one of many reasons – one fundamental reason is that we in the scientific community are not able to communicate precision on risk.

“Science on tipping point risk is so important because so many actors are using the uncertainty ranges as an excuse for not acting. So, as long as the AMOC continues to have medium confidence, then you can go on forever kicking the can down the road.”

The Exeter meeting comes against a backdrop of cuts to climate science funding in the US, including to the budget of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA).

Lenton said the tipping-point community was “traumatised” by the developments – “especially [on behalf] of colleagues in the US” who had lost their jobs. He added:

“It is already influencing things. If we lose NOAA and we lose our state-of-the-art assessment of the state of the oceans – these are dangerous erosions of our ability to sense whether the Earth system is destabilising or not. This is a fundamental loss.”

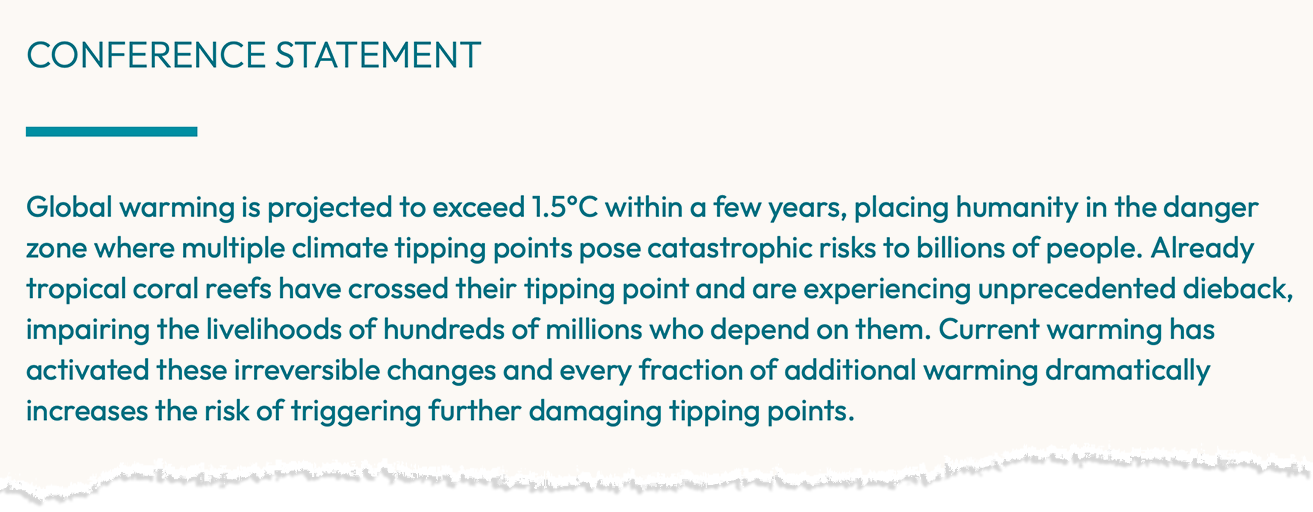

During the conference, the convenors drafted a conference statement, which they encouraged delegates to endorse.

With global warming approaching the Paris Agreement 1.5C limit, the statement warns that this places “humanity in the danger zone where multiple climate tipping points pose catastrophic risks to billions of people”.

It says that the “window for preventing these cascading climate dynamics is rapidly closing”, adding:

“We join the COP30 presidency in calling on governments to enact policies that help trigger positive tipping points in their economies and societies, which generate self-propelling change in technologies and behaviours towards zero emissions.”

The statement concludes by arguing that “decisive policy and civil society action” is needed for the world to “tip its trajectory from facing unmanageable climate tipping point risks to seizing positive tipping point opportunities”.

The post Tipping points: Window to avoid irreversible climate impacts is ‘rapidly closing’ appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Tipping points: Window to avoid irreversible climate impacts is ‘rapidly closing’

Greenhouse Gases

DeBriefed 6 February 2026: US secret climate panel ‘unlawful’ | China’s clean energy boon | Can humans reverse nature loss?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Secrets and layoffs

UNLAWFUL PANEL: A federal judge ruled that the US energy department “violated the law when secretary Chris Wright handpicked five researchers who rejected the scientific consensus on climate change to work in secret on a sweeping government report on global warming”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper explained that a 1972 law “does not allow agencies to recruit or rely on secret groups for the purposes of policymaking”. A Carbon Brief factcheck found more than 100 false or misleading claims in the report.

DARKNESS DESCENDS: The Washington Post reportedly sent layoff notices to “at least 14” of its climate journalists, as part of a wider move from the newspaper’s billionaire owner, Jeff Bezos, to eliminate 300 jobs at the publication, claimed Climate Colored Goggles. After the layoffs, the newspaper will have five journalists left on its award-winning climate desk, according to the substack run by a former climate reporter at the Los Angeles Times. It comes after CBS News laid off most of its climate team in October, it added.

WIND UNBLOCKED: Elsewhere, a separate federal ruling said that a wind project off the coast of New York state can continue, which now means that “all five offshore wind projects halted by the Trump administration in December can resume construction”, said Reuters. Bloomberg added that “Ørsted said it has spent $7bn on the development, which is 45% complete”.

Around the world

- CHANGING TIDES: The EU is “mulling a new strategy” in climate diplomacy after struggling to gather support for “faster, more ambitious action to cut planet-heating emissions” at last year’s UN climate summit COP30, reported Reuters.

- FINANCE ‘CUT’: The UK government is planning to cut climate finance by more than a fifth, from £11.6bn over the past five years to £9bn in the next five, according to the Guardian.

- BIG PLANS: India’s 2026 budget included a new $2.2bn funding push for carbon capture technologies, reported Carbon Brief. The budget also outlined support for renewables and the mining and processing of critical minerals.

- MOROCCO FLOODS: More than 140,000 people have been evacuated in Morocco as “heavy rainfall and water releases from overfilled dams led to flooding”, reported the Associated Press.

- CASHFLOW: “Flawed” economic models used by governments and financial bodies “ignor[e] shocks from extreme weather and climate tipping points”, posing the risk of a “global financial crash”, according to a Carbon Tracker report covered by the Guardian.

- HEATING UP: The International Olympic Committee is discussing options to hold future winter games earlier in the year “because of the effects of warmer temperatures”, said the Associated Press.

54%

The increase in new solar capacity installed in Africa over 2024-25 – the continent’s fastest growth on record, according to a Global Solar Council report covered by Bloomberg.

Latest climate research

- Arctic warming significantly postpones the retreat of the Afro-Asian summer monsoon, worsening autumn rainfall | Environmental Research Letters

- “Positive” images of heatwaves reduce the impact of messages about extreme heat, according to a survey of 4,000 US adults | Environmental Communication

- Greenland’s “peripheral” glaciers are projected to lose nearly one-fifth of their total area and almost one-third of their total volume by 2100 under a low-emissions scenario | The Cryosphere

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

Captured

Solar power, electric vehicles and other clean-energy technologies drove more than a third of the growth in China’s economy in 2025 – and more than 90% of the rise in investment, according to new analysis for Carbon Brief (shown in blue above). Clean-energy sectors contributed a record 15.4tn yuan ($2.1tn) in 2025, some 11.4% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) – comparable to the economies of Brazil or Canada, the analysis said.

Spotlight

Can humans reverse nature decline?

This week, Carbon Brief travelled to a UN event in Manchester, UK to speak to biodiversity scientists about the chances of reversing nature loss.

Officials from more than 150 countries arrived in Manchester this week to approve a new UN report on how nature underpins economic prosperity.

The meeting comes just four years before nations are due to meet a global target to halt and reverse biodiversity loss, agreed in 2022 under the landmark “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework” (GBF).

At the sidelines of the meeting, Carbon Brief spoke to a range of scientists about humanity’s chances of meeting the 2030 goal. Their answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Dr David Obura, ecologist and chair of Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)

We can’t halt and reverse the decline of every ecosystem. But we can try to “bend the curve” or halt and reverse the drivers of decline. That’s the economic drivers, the indirect drivers and the values shifts we need to have. What the GBF aspires to do, in terms of halting and reversing biodiversity loss, we can put in place the enabling drivers for that by 2030, but we won’t be able to do it fast enough at this point to halt [the loss] of all ecosystems.

Dr Luthando Dziba, executive secretary of IPBES

Countries are due to report on progress by the end of February this year on their national strategies to the Convention on Biological Diversity [CBD]. Once we get that, coupled with a process that is ongoing within the CBD, which is called the global stocktake, I think that’s going to give insights on progress as to whether this is possible to achieve by 2030…Are we on the right trajectory? I think we are and hopefully we will continue to move towards the final destination of having halted biodiversity loss, but also of living in harmony with nature.

Prof Laura Pereira, scientist at the Global Change Institute at Wits University, South Africa

At the global level, I think it’s very unlikely that we’re going to achieve the overall goal of halting biodiversity loss by 2030. That being said, I think we will make substantial inroads towards achieving our longer term targets. There is a lot of hope, but we’ve also got to be very aware that we have not necessarily seen the transformative changes that are going to be needed to really reverse the impacts on biodiversity.

Dr David Cooper, chair of the UK’s Joint Nature Conservation Committee and former executive secretary of the Convention on Biological Diversity

It’s important to look at the GBF as a whole…I think it is possible to achieve those targets, or at least most of them, and to make substantial progress towards them. It is possible, still, to take action to put nature on a path to recovery. We’ll have to increasingly look at the drivers.

Prof Andrew Gonzalez, McGill University professor and co-chair of an IPBES biodiversity monitoring assessment

I think for many of the 23 targets across the GBF, it’s going to be challenging to hit those by 2030. I think we’re looking at a process that’s starting now in earnest as countries [implement steps and measure progress]…You have to align efforts for conserving nature, the economics of protecting nature [and] the social dimensions of that, and who benefits, whose rights are preserved and protected.

Neville Ash, director of the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre

The ambitions in the 2030 targets are very high, so it’s going to be a stretch for many governments to make the actions necessary to achieve those targets, but even if we make all the actions in the next four years, it doesn’t mean we halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. It means we put the action in place to enable that to happen in the future…The important thing at this stage is the urgent action to address the loss of biodiversity, with the result of that finding its way through by the ambition of 2050 of living in harmony with nature.

Prof Pam McElwee, Rutgers University professor and co-chair of an IPBES “nexus assessment” report

If you look at all of the available evidence, it’s pretty clear that we’re going to keep experiencing biodiversity decline. I mean, it’s fairly similar to the 1.5C climate target. We are not going to meet that either. But that doesn’t mean that you slow down the ambition…even though you recognise that we probably won’t meet that specific timebound target, that’s all the more reason to continue to do what we’re doing and, in fact, accelerate action.

Watch, read, listen

OIL IMPACTS: Gas flaring has risen in the Niger Delta since oil and gas major Shell sold its assets in the Nigerian “oil hub”, a Climate Home News investigation found.

LOW SNOW: The Washington Post explored how “climate change is making the Winter Olympics harder to host”.

CULTURE WARS: A Media Confidential podcast examined when climate coverage in the UK became “part of the culture wars”.

Coming up

- 2-8 February: 12th session of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), Manchester, UK

- 8 February: Japanese general election

- 8 February: Portugal presidential election

- 11 February: Barbados general election

- 11-12 February: UN climate chief Simon Stiell due to speak in Istanbul, Turkey

Pick of the jobs

- UK Met Office, senior climate science communicator | Salary: £43,081-£46,728. Location: Exeter, UK

- Canadian Red Cross, programme officer, Indigenous operations – disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation | Salary: $56,520-$60,053. Location: Manitoba, Canada

- Aldersgate Group, policy officer | Salary: £33,949-£39,253. Location: London (hybrid)

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 6 February 2026: US secret climate panel ‘unlawful’ | China’s clean energy boon | Can humans reverse nature loss? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

China Briefing 5 February 2026: Clean energy’s share of economy | Record renewables | Thawing relations with UK

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s China Briefing.

China Briefing handpicks and explains the most important climate and energy stories from China over the past fortnight. Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Solar and wind eclipsed coal

‘FIRST TIME IN HISTORY’: China’s total power capacity reached 3,890 gigawatts (GW) in 2025, according to a National Energy Administration (NEA) data release covered by industry news outlet International Energy Net. Of this, it said, solar capacity rose 35% to 1,200GW and wind capacity was up 23% to 640GW, while thermal capacity – which is mostly coal – grew 6% to just over 1,500GW. This marks the “first time in history” that wind and solar capacity has outranked coal capacity in China’s power mix, reported the state-run newspaper China Daily. China’s grid-related energy storage capacity exceeded 213GW in 2025, said state news agency Xinhua. Meanwhile, clean-energy industries “drove more than 90%” of investment growth and more than half of GDP growth last year, said the Guardian in its coverage of new analysis for Carbon Brief. (See more in the spotlight below.)

DAWN FOR SOLAR: Solar power capacity alone may outpace coal in 2026, according to projections by the China Electricity Council (CEC), reported business news outlet 21st Century Business Herald. It added that non-fossil sources could account for 63% of the power mix this year, with coal falling to 31%. Separately, the China Renewable Energy Society said that annual wind-power additions could grow by between 600-980GW over the next five years, with annual additions of 120GW expected until 2028, said industry news outlet China Energy Net. China Energy Net also published the full CEC report.

STATE MEDIA VOICE: Xinhua published several energy- and climate-related articles in a series on the 15th five-year plan. One said that becoming a low-carbon energy “powerhouse” will support decarbonisation efforts, strengthen industrial innovation and improve China’s “global competitive edge and standing”. Another stated that coal consumption is “expected” to peak around 2027, with continued “growth” in the power and chemicals sector, while oil has already peaked. A third noted that distributed energy systems better matched the “characteristics of renewable energy” than centralised ones, but warned against “blind” expansion and insufficient supporting infrastructure. Others in the series discussed biodiversity and environmental protection and recycling of clean-energy technology. Meanwhile, the communist party-affiliated People’s Daily said that oil will continue to play a “vital role” in China, even after demand peaks.

Starmer and Xi endorsed clean-energy cooperation

CLIMATE PARTNERSHIP: UK prime minister Keir Starmer and Chinese president Xi Jinping pledged in Beijing to deepen cooperation on “green energy”, reported finance news outlet Caixin. They also agreed to establish a “China-UK high-level climate and nature partnership”, said China Daily. Xi told Starmer that the two countries should “carry out joint research and industrial transformation” in new energy and low-carbon technologies, according to Xinhua. It also cited Xi as saying China “hopes” the UK will provide a “fair” business environment for Chinese companies.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “China Briefing” email newsletter. All you need to know about the latest developments relating to China and climate change. Sent to your inbox every Thursday.

OCTOPUS OVERSEAS: During the visit, UK power-trading company Octopus Energy and Chinese energy services firm PCG Power announced they would be starting a new joint venture in China, named Bitong Energy, reported industry news outlet PV Magazine. The move “marks a notable direct entry” of a foreign company into China’s “tightly regulated electricity market”, said Caixin.

PUSH AND PULL: UK policymakers also visited Chinese clean-energy technology manufacturer Envision in Shanghai, reported finance news outlet Yicai. It quoted UK business secretary Peter Kyle emphasising that partnering with companies “like Envision” on sustainability is a “really important part of our future”, particularly in terms of job creation in the UK. Trade minister Chris Bryant told Radio Scotland Breakfast that the government will decide on Chinese wind turbine manufacturer Mingyang’s plans for a Scotland factory “soon”. Researchers at the thinktank Oxford Institute for Energy Studies wrote in a guest post for Carbon Brief that greater Chinese competition in Europe’s wind market could “help spur competition in Europe”, if localisation rules and “other guardrails” are applied.

More China news

- LIFE SUPPORT: China will update its coal capacity payment mechanism, which will raise thresholds for coal-fired power plants and expand to cover gas-fired power and pumped and new-energy storage, reported current affairs outlet China News.

- FRONTIER TECH: The world’s “largest compressed-air power storage plant” has begun operating in China, said Bloomberg.

- PARTNERSHIP A ‘MISTAKE’: The EU launched a “foreign subsidies” probe into Chinese wind turbine company Goldwind, said the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post. EU climate chief Wopke Hoekstra said the bloc must resist China’s pull in clean technologies, according to Bloomberg.

- TRADE SPAT: The World Trade Organization “backed a complaint by China” that the US Inflation Reduction Act “discriminated against” Chinese cleantech exports, said Reuters.

- NEW RULES: China has set “new regulations” for the Waliguan Baseline Observatory, which provides “key scientific references for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change”, said the People’s Daily.

Captured

New or reactivated proposals for coal-fired power plants in China totalled 161GW in 2025, according to a new report covered by Carbon Brief.

Spotlight

Clean energy drove China’s economic growth in 2025

New analysis for Carbon Brief finds that clean-energy sectors contributed the equivalent of $2.1tn to China’s economy last year, making it a key driver of growth. However, headwinds in 2026 could restrict growth going forward – especially for the solar sector.

Below is an excerpt from the article, which can be read in full on Carbon Brief’s website.

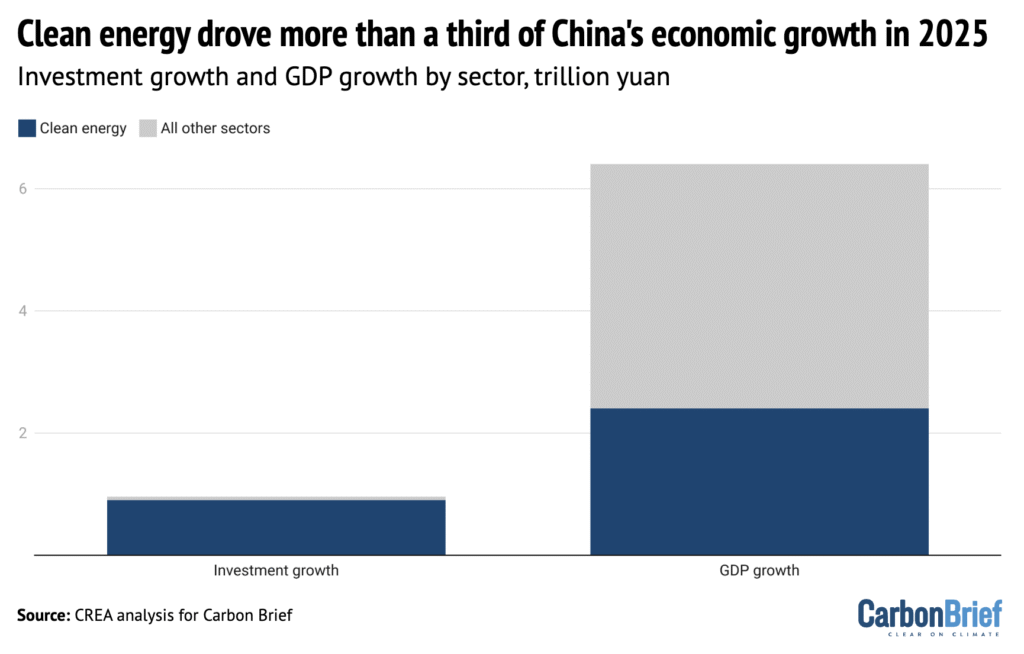

Solar power, electric vehicles (EVs) and other clean-energy technologies drove more than a third of the growth in China’s economy in 2025 – and more than 90% of the rise in investment.

Clean-energy sectors contributed a record 15.4tn yuan ($2.1tn) in 2025, some 11.4% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP)

Analysis shows that China’s clean-energy sectors nearly doubled in real value between 2022-25 and – if they were a country – would now be the 8th-largest economy in the world.

These investments in clean-energy manufacturing represent a large bet on the energy transition in China and overseas, creating an incentive for the government and enterprises to keep the boom going.

However, there is uncertainty about what will happen this year and beyond, particularly due to a new pricing system, worsening industrial “overcapacity” and trade tensions.

Outperforming the wider economy

China’s clean-energy economy continues to grow far more quickly than the wider economy, making an outsized contribution to annual growth.

Without these sectors, China’s GDP would have expanded by 3.5% in 2025 instead of the reported 5.0%, missing the target of “around 5%” growth by a wide margin.

Clean energy made a crucial contribution during a challenging year, when promoting economic growth was the foremost aim for policymakers.

In 2024, EVs and solar had been the largest growth drivers. In 2025, it was EVs and batteries, which delivered 44% of the economic impact and more than half of the growth of the clean-energy industries.

The next largest subsector was clean-power generation, transmission and storage, which made up 40% of the contribution to GDP and 30% of the growth in 2025.

Within the electricity sector, the largest drivers were growth in investment in wind and solar power generation capacity, along with growth in power output from solar and wind, followed by the exports of solar-power equipment and materials.

But investment in solar-panel supply chains, a major growth driver in 2022-23, continued to fall for the second year, as the government made efforts to rein in overcapacity and “irrational” price competition.

Headwinds for solar

Ongoing investment of hundreds of billions of dollars represents a gigantic bet on a continuing global energy transition.

However, developments next year and beyond are unclear, particularly for solar. A new pricing system for renewable power is creating uncertainty, while central government targets have been set far below current rates of clean-electricity additions.

Investment in solar-power generation and solar manufacturing declined in the second half of the year.

The reduction in the prices of clean-energy technology has been so dramatic that when the prices for GDP statistics are updated, the sectors’ contribution to real GDP – adjusted for inflation or, in this case deflation – will be revised down.

Nevertheless, the key economic role of the industry creates a strong motivation to keep the clean-energy boom going. A slowdown in the domestic market could also undermine efforts to stem overcapacity and inflame trade tensions by increasing pressure on exports to absorb supply.

Local governments and state-owned enterprises will also influence the outlook for the sector.

Provincial governments have a lot of leeway in implementing the new electricity markets and contracting systems for renewable power generation. The new five-year plans, to be published this year, will, therefore, be of major importance.

This spotlight was written for Carbon Brief by Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), and Belinda Schaepe, China policy analyst at CREA. CREA China analysts Qi Qin and Chengcheng Qiu contributed research.

Watch, read, listen

PROVINCE INFLUENCE: The Institute for Global Decarbonization Progress, a Beijing-based thinktank, published a report examining the climate-related statements in provincial recommendations for the 15th five-year plan.

‘PIVOT’?: The Outrage + Optimism podcast spoke with the University of Bath’s Dr Yixian Sun about whether China sees itself as a climate leader and what its role in climate negotiations could be going forward.

COOKING FOR CLEAN-TECH: Caixin covered rising demand for China’s “gutter oil” as companies “scramble” to decarbonise.

DON’T GO IT ALONE: China News broadcast the Chinese foreign ministry’s response to the withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement, with spokeswoman Mao Ning saying “no country can remain unaffected” by climate change.

$6.8tn

The current size of China’s green-finance economy, including loans, bonds and equity, according to Dr Ma Jun, the Institute of Finance and Sustainability’s president,in a report launch event attended by Carbon Brief. Dr Ma added that “green loans” make up 16% of all loans in China, with some areas seeing them take a 34% share.

New science

- China’s official emissions inventories have overestimated its hydrofluorocarbon emissions by an average of 117m tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (mtCO2e) every year since 2017 | Nature Geoscience

- “Intensified forest management efforts” in China from 2010 onwards have been linked to an acceleration in carbon absorption by plants and soils | Communications Earth and Environment

Recently published on WeChat

China Briefing is written by Anika Patel and edited by Simon Evans. Please send tips and feedback to china@carbonbrief.org

The post China Briefing 5 February 2026: Clean energy’s share of economy | Record renewables | Thawing relations with UK appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Greenhouse Gases

Analysis: Clean energy drove more than a third of China’s GDP growth in 2025

Solar power, electric vehicles (EVs) and other clean-energy technologies drove more than a third of the growth in China’s economy in 2025 – and more than 90% of the rise in investment.

Clean-energy sectors contributed a record 15.4tn yuan ($2.1tn) in 2025, some 11.4% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) – comparable to the economies of Brazil or Canada.

The new analysis for Carbon Brief, based on official figures, industry data and analyst reports, shows that China’s clean-energy sectors nearly doubled in real value between 2022-25 and – if they were a country – would now be the 8th-largest economy in the world.

Other key findings from the analysis include:

- Without clean-energy sectors, China would have missed its target for GDP growth of “around 5%”, expanding by 3.5% in 2025 instead of the reported 5.0%.

- Clean-energy industries are expanding much more quickly than China’s economy overall, with their annual growth rate accelerating from 12% in 2024 to 18% in 2025.

- The “new three” of EVs, batteries and solar continue to dominate the economic contribution of clean energy in China, generating two-thirds of the value added and attracting more than half of all investment in the sectors.

- China’s investments in clean energy reached 7.2tn yuan ($1.0tn) in 2025, roughly four times the still sizable $260bn put into fossil-fuel extraction and coal power.

- Exports of clean-energy technologies grew rapidly in 2025, but China’s domestic market still far exceeds the export market in value for Chinese firms.

These investments in clean-energy manufacturing represent a large bet on the energy transition in China and overseas, creating an incentive for the government and enterprises to keep the boom going.

However, there is uncertainty about what will happen this year and beyond, particularly for solar power, where growth has slowed in response to a new pricing system and where central government targets have been set far below the recent rate of expansion.

An ongoing slowdown could turn the sectors into a drag on GDP, while worsening industrial “overcapacity” and exacerbating trade tensions.

Yet, even if central government targets in the next five-year plan are modest, those from local governments and state-owned enterprises could still drive significant growth in clean energy.

This article updates analysis previously reported for 2023 and 2024.

Clean-energy sectors outperform wider economy

China’s clean-energy economy continues to grow far more quickly than the wider economy. This means that it is making an outsize contribution to annual economic growth.

The figure below shows that clean-energy technologies drove more than a third of the growth in China’s economy overall in 2025 and more than 90% of the net rise in investment.

In 2022, China’s clean-energy economy was worth an estimated 8.4tn yuan ($1.2tn). By 2025, the sectors had nearly doubled in value to 15.4tn yuan ($2.1tn).

This is comparable to the entire output of Brazil or Canada and positions the Chinese clean-energy industry as the 8th-largest economy in the world. Its value is roughly half the size of the economy of India – the world’s fourth largest – or of the US state of California.

The outperformance of the clean-energy sectors means that they are also claiming a rising share of China’s economy overall, as shown in the figure below.

This share has risen from 7.3% of China’s GDP in 2022 to 11.4% in 2025.

Without clean-energy sectors, China’s GDP would have expanded by 3.5% in 2025 instead of the reported 5.0%, missing the target of “around 5%” growth by a wide margin.

Clean energy thus made a crucial contribution during a challenging year, when promoting economic growth was the foremost aim for policymakers.

The table below includes a detailed breakdown by sector and activity.

| Sector | Activity | Value in 2025, CNY bln | Value in 2025, USD bln | Year-on-year growth | Growth contribution | Value contribution | Value in 2025, CNY trn | Value in 2024, CNY trn | Value in 2023, CNY trn | Value in 2022, CNY trn |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| EVs | Investment: manufacturing capacity | 1,643 | 228 | 18% | 10.4% | 10.7% | 1.6 | 1.4 | 1.2 | 0.9 |

| EVs | Investment: charging infrastructure | 192 | 27 | 58% | 2.9% | 1.2% | 0.192 | 0.122 | 0.1 | 0.08 |

| EVs | Production of vehicles | 3,940 | 548 | 29% | 36.4% | 25.6% | 3.94 | 3.065 | 2.26 | 1.65 |

| Batteries | Investment: battery manufacturing | 277 | 38 | 35% | 3.0% | 1.8% | 0.277 | 0.205 | 0.32 | 0.15 |

| Batteries | Exports: batteries | 724 | 101 | 51% | 10.1% | 4.7% | 0.724 | 0.48 | 0.46 | 0.34 |

| Solar power | Investment: power generation capacity | 1,182 | 164 | 15% | 6.3% | 7.7% | 1.182 | 1.031 | 0.808 | 0.34 |

| Solar power | Investment: manufacturing capacity | 506 | 70 | -23% | -6.5% | 3.3% | 0.506 | 0.662 | 0.95 | 0.51 |

| Solar power | Electricity generation | 491 | 68 | 33% | 5.1% | 3.2% | 0.491 | 0.369 | 0.26 | 0.19 |

| Solar power | Exports of components | 681 | 95 | 21% | 4.9% | 4.4% | 0.681 | 0.562 | 0.5 | 0.35 |

| Wind power | Investment: power generation capacity, onshore | 612 | 85 | 47% | 8.1% | 4.0% | 0.612 | 0.417 | 0.397 | 0.21 |

| Wind power | Investment: power generation capacity, offshore | 96 | 13 | 98% | 2.0% | 0.6% | 0.096 | 0.048 | 0.086 | 0.06 |

| Wind power | Electricity generation | 510 | 71 | 13% | 2.4% | 3.3% | 0.51 | 0.453 | 0.4 | 0.34 |

| Nuclear power | Investment: power generation capacity | 173 | 24 | 18% | 1.1% | 1.1% | 0.17 | 0.15 | 0.09 | 0.07 |

| Nuclear power | Electricity generation | 216 | 30 | 8% | 0.7% | 1.4% | 0.216 | 0.2 | 0.19 | 0.19 |

| Hydropower | Investment: power generation capacity | 54 | 7 | -7% | -0.2% | 0.3% | 0.05 | 0.06 | 0.06 | 0.06 |

| Hydropower | Electricity generation | 582 | 81 | 3% | 0.6% | 3.8% | 0.582 | 0.567 | 0.51 | 0.51 |

| Rail transportation | Investment | 902 | 125 | 6% | 2.1% | 5.8% | 0.902 | 0.851 | 0.764 | 0.714 |

| Rail transportation | Transport of passengers and goods | 1,020 | 142 | 3% | 1.3% | 6.6% | 1.02 | 0.99 | 0.964 | 0.694 |

| Electricity transmission | Investment: transmission capacity | 644 | 90 | 6% | 1.5% | 4.2% | 0.64 | 0.61 | 0.53 | 0.5 |

| Electricity transmission | Transmission of clean power | 52 | 7 | 14% | 0.3% | 0.3% | 0.052 | 0.046 | 0.04 | 0.04 |

| Energy storage | Investment: Pumped hydro | 53 | 7 | 5% | 0.1% | 0.3% | 0.05 | 0.05 | 0.04 | 0.03 |

| Energy storage | Investment: Grid-connected batteries | 232 | 32 | 52% | 3.3% | 1.5% | 0.232 | 0.152 | 0.08 | 0.02 |

| Energy storage | Investment: Electrolysers | 11 | 2 | 29% | 0.1% | 0.1% | 0.011 | 0.009 | 0 | 0 |

| Energy efficiency | Revenue: Energy service companies | 620 | 86 | 17% | 3.8% | 4.0% | 0.62 | 0.528003 | 0.52 | 0.45 |

| Total | Investments | 7,198 | 1001 | 15% | 38.2% | 46.7% | 7.20 | 6.28 | 6.00 | 4.11 |

| Total | Production of goods and services | 8,216 | 1,143 | 22% | 61.8% | 53.3% | 8.22 | 6.73 | 5.58 | 4.32 |

| Total | Total GDP contribution | 15,414 | 2144 | 18% | 100.0% | 100.0% | 15.41 | 13.01 | 11.58 | 8.42 |

EVs and batteries were the largest drivers of GDP growth

In 2024, EVs and solar had been the largest growth drivers. In 2025, it was EVs and batteries, which delivered 44% of the economic impact and more than half of the growth of the clean-energy industries. This was due to strong growth in both output and investment.

The contribution to nominal GDP growth – unadjusted for inflation – was even larger, as EV prices held up year-on-year while the economy as a whole suffered from deflation. Investment in battery manufacturing rebounded after a fall in 2024.

The major contribution of EVs and batteries is illustrated in the figure below, which shows both the overall size of the clean-energy economy and the sectors that added the most to the rise from year to year.

The next largest subsector was clean-power generation, transmission and storage, which made up 40% of the contribution to GDP and 30% of the growth in 2025.

Within the electricity sector, the largest drivers were growth in investment in wind and solar power generation capacity, along with growth in power output from solar and wind, followed by the exports of solar-power equipment and materials.

Investment in solar-panel supply chains, a major growth driver in 2022-23, continued to fall for the second year. This was in line with the government’s efforts to rein in overcapacity and “irrational” price competition in the sector.

Finally, rail transportation was responsible for 12% of the total economic output of the clean-energy sectors, but saw relatively muted growth year-on-year, with revenue up 3% and investment by 6%.

Note that the International Energy Agency (IEA) world energy investment report projected that China invested $627bn in clean energy in 2025, against $257bn in fossil fuels.

For the same sectors as the IEA report, this analysis puts the value of clean-energy investment in 2025 at a significantly more conservative $430bn. The higher figures in this analysis overall are therefore the result of wider sectoral coverage.

Electric vehicles and batteries

EVs and vehicle batteries were again the largest contributors to China’s clean-energy economy in 2025, making up an estimated 44% of value overall.

Of this total, the largest share of both total value and growth came from the production of battery EVs and plug-in hybrids, which expanded 29% year-on-year. This was followed by investment into EV manufacturing, which grew 18%, after slower growth rates in 2024.

Investment in battery manufacturing also rebounded after a drop in 2024, driven by new battery technology and strong demand from both domestic and international markets. Battery manufacturing investment grew by 35% year-on-year to 277bn yuan.

The share of electric vehicles (EVs) will have reached 12% of all vehicles on the road by the end of 2025, up from 9% a year earlier and less than 2% just five years ago.

The share of EVs in the sales of all new vehicles increased to 48%, from 41% in 2024, with passenger cars crossing the 50% threshold. In November, EV sales crossed the 60% mark in total sales and they continue to drive overall automotive sales growth, as shown below.

Electric trucks experienced a breakthrough as their market share rose from 8% in the first nine months of 2024 to 23% in the same period in 2025.

Policy support for EVs continues, for example, with a new policy aiming to nearly double charging infrastructure in the next three years.

Exports grew even faster than the domestic market, but the vast majority of EVs continue to be sold domestically. In 2025, China produced 16.6m EVs, rising 29% year-on-year. While exports accounted for only 21% or 3.4m EVs, they grew by 86% year-on-year. Top export destinations for Chinese EVs were western Europe, the Middle East and Latin America.

The value of batteries exported also grew rapidly by 41% year-on-year, becoming the third largest growth driver of the GDP. Battery exports largely went to western Europe, north America and south-east Asia.

In contrast with deflationary trends in the price of many clean-energy technologies, average EV prices have held up in 2025, with a slight increase in average price of new models, after discounts. This also means that the contribution of the EV industry to nominal GDP growth was even more significant, given that overall producer prices across the economy fell by 2.6%. Battery prices continued to drop.

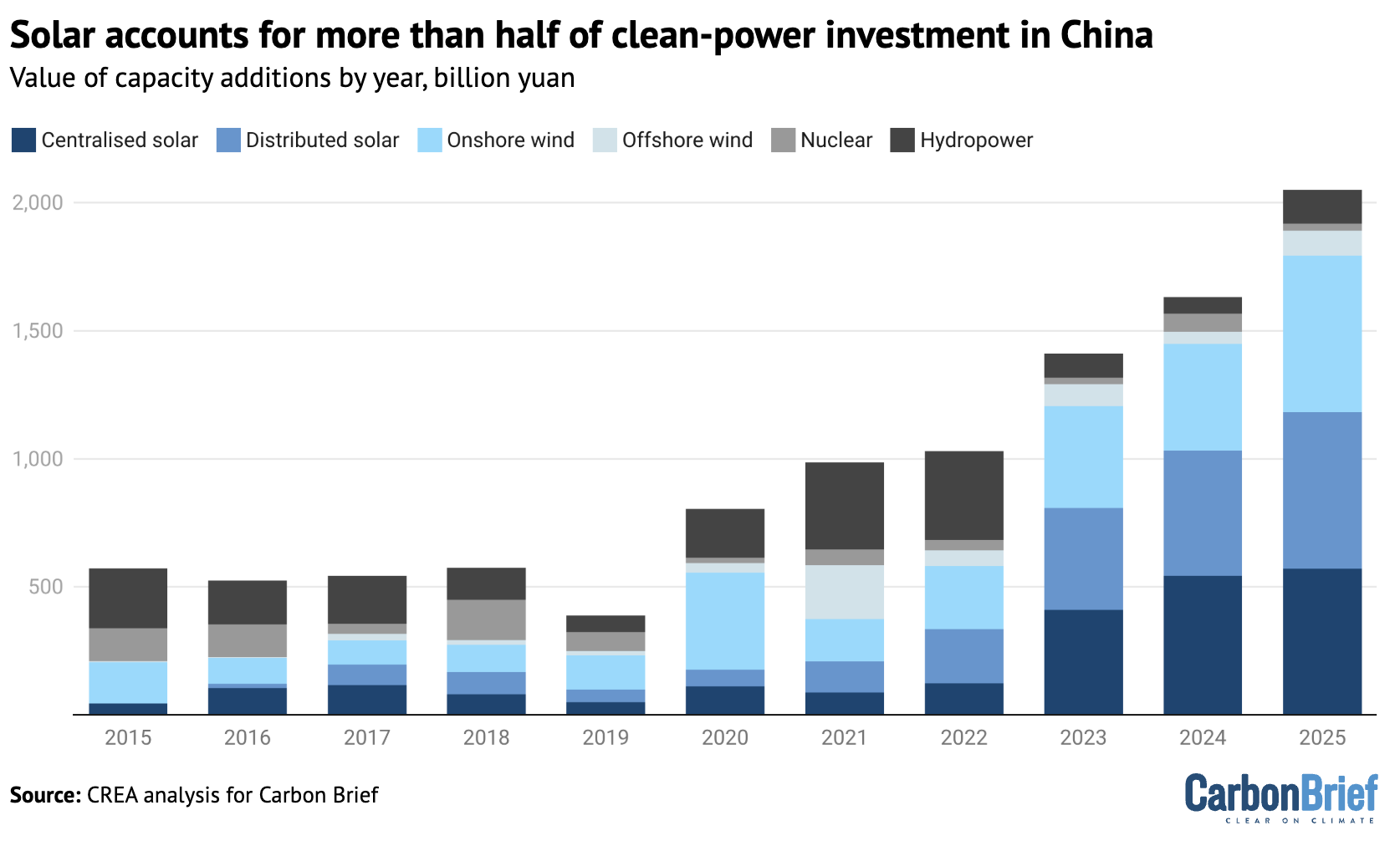

Clean-power generation

The solar power sector generated 19% of the total value of the clean-energy industries in 2025, adding 2.9tn yuan ($41bn) to the national economy.

Within this, investment in new solar power plants, at 1.2tn yuan ($160bn), was the largest driver, followed by the value of solar technology exports and by the value of the power generated from solar. Investment in manufacturing continued to fall after the wave of capacity additions in 2023, reaching 0.5tn yuan ($72bn), down 23% year-on-year.

In 2025, China achieved another new record of wind and solar capacity additions. The country installed a total of 315GW solar and 119GW wind capacity, adding more solar and two times as much wind as the rest of the world combined.

Clean energy accounted for 90% of investment in power generation, with solar alone covering 50% of that. As a result, non-fossil power made up 42% of total power generation, up from 39% in 2024.

However, a new pricing policy for new solar and wind projects and modest targets for capacity growth have created uncertainty about whether the boom will continue.

Under the new policy, new clean-power generation has to compete on price against existing coal power in markets that place it at a disadvantage in some key ways.

At the same time, the electricity markets themselves are still being introduced and developed, creating investment uncertainty.

Investment in solar power generation increased year-on-year by 15%, but experienced a strong stop-and-go cycle. Developers rushed to finish projects ahead of the new pricing policy coming into force in June and then again towards the end of the year to finalise projects ahead of the end of the current 14th five-year plan.

Investment in the solar sector as a whole was stable year-on-year, with the decline in manufacturing capacity investment balanced by continued growth in power generation capacity additions. This helped shore up the utilisation of manufacturing plants, in line with the government’s aim to reduce “disorderly” price competition.

By late 2025, China’s solar manufacturing capacity reached an estimated 1,200GW per year, well ahead of the global capacity additions of around 650GW in 2025. Manufacturers can now produce far more solar panels than the global market can absorb, with fierce competition leading to historically low profitability.

China’s policymakers have sought to address the issue since mid-2024, warning against “involution”, passing regulations and convening a sector-wide meeting to put pressure on the industry. This is starting to yield results, with losses narrowing in the third quarter of 2025.

The volume of exports of solar panels and components reached a record high in 2025, growing 19% year-on-year. In particular, exports of cells and wafers increased rapidly by 94% and 52%, while panel exports grew only by 4%.

This reflects the growing diversification of solar-supply chains in the face of tariffs and with more countries around the world building out solar panel manufacturing capacity. The nominal value of exports fell 8%, however, due to a fall in average prices and a shift to exporting upstream intermediate products instead of finished panels.

Hydropower, wind and nuclear were responsible for 15% of the total value of the clean-energy sectors in 2025, adding some 2.2tn yuan ($310bn) to China’s GDP in 2025.

Nearly two-thirds of this (1.3tn yuan, $180bn) came from the value of power generation from hydropower, wind and nuclear, with investment in new power generation projects contributing the rest.

Power generation grew 33% from solar, 13% from wind, 3% from hydropower and 8% from nuclear.

Within power generation investment, solar remained the largest segment by value – as shown in the figure below – but wind-power generation projects were the largest contributor to growth, overtaking solar for the first time since 2020.

In particular, offshore wind power capacity investment rebounded as expected, doubling in 2025 after a sharp drop in 2024.

Investment in nuclear projects continued to grow but remains smaller in total terms, at 17bn yuan. Investment in conventional hydropower continued to decline by 7%.

Electricity storage and grids

Electricity transmission and storage were responsible for 6% of the total value of the clean-energy sectors in 2025, accounting for 1.0 tn yuan ($140bn).

The most valuable sub-segment was investment in power grids, growing 6% in 2025 and reaching $90bn. This was followed by investment in energy storage, including pumped hydropower, grid-connected battery storage and hydrogen production.

Investment in grid-connected batteries saw the largest year-on-year growth, increasing by 50%, while investments in electrolysers also grew by 30%. The transmission of clean power increased an estimated 13%, due to rapid growth in clean-power generation.

China’s total electricity storage capacity reached more than 213GW, with battery storage capacity crossing 145GW and pumped hydro storage at 69GW. Some 66GW of battery storage capacity was added in 2025, up 52% year-on-year and accounting for more than 40% of global capacity additions.

Notably, capacity additions accelerated in the second half of the year, with 43GW added, compared with the first half, which saw 23GW of new capacity.

The battery storage market initially slowed after the renewable power pricing policy, which banned storage mandates after May, but this was quickly replaced by a “market-driven boom”. Provincial electricity spot markets, time-of-day tariffs and increasing curtailment of solar power all improved the economics of adding storage.

By the end of 2025, China’s top five solar manufacturers had all entered the battery storage market, making a shift in industry strategy.

Investment in pumped hydropower continued to increase, with 15GW of new capacity permitted in the first half of 2025 alone and 3GW entering operation.

Railways