At COP28 in Dubai, Carbon Brief’s Anika Patel spoke with Prof Pan Jiahua, vice-chair of the national expert panel on climate change of China, about his ideas for how to move to a zero-carbon future.

This interview covers a wide range of topics, including China’s stance on fossil fuels, the concept of an “ecological civilisation”, the usefulness of a global “loss-and-damage fund”, and prospects for distributed solar and power market reform in China. It is transcribed in full below, following a summary of key quotes.

China’s national expert committee on climate change, of which Prof Pan is vice-chair, is an advisory body under the national leaders group on climate change, energy-saving and emissions reduction.

He is also a member of the Chinese Academy of Social Sciences and director of its Research Center for Sustainable Development, as well as director of Beijing University of Technology’s Institute of Eco-Civilization Studies and a member of the China Carbon Neutral Fifty Forum.

- On the philosophy of ‘ecological civilisation’: “Human beings, for their own benefit – they ignored the benefit of nature. The welfare of nature. We expose nature, we deplete our natural resources…[Under ecological civilisation] the basic idea [is] that [if we can achieve] harmony with nature [and] harmony among our nations, then we can go long into the future.”

- On the success of UN climate summits: “COP is the only thing that [has lasted] over 30 years…We have different views, different arguments, different interests but, all in all, we’ve come a long way…we agreed the Paris targets – in 1990 nobody would believe that [was possible].”

- On the ‘loss-and-damage fund’: “Losses and damages should be compensated, but not in a way that we divert our energy and resources for [the sake of] compensation. We should use all our energy, resources, spirits – everything – for the zero-carbon transition.”

- On the ‘climate paradox’: “If you divert the limited resources for compensating losses and damages, then the zero-carbon transition would be delayed. And if you delay such a transition, there will be more and more losses and damages. I call this the climate paradox.”

- On tripling renewable energy: “Tripling renewable energy is not enough. Why are we only tripling? Why not more and more, the more the better. Because look at China – [we] doubled and doubled and doubled [our renewable energy] all the time. This year we doubled installed capacity over the last year. Why shouldn’t we do more than just tripling?”

- On replacing energy infrastructure: “Renewables would not require a huge amount of investment in infrastructure. Fossil fuels, coal electricity generation – the investment is very capital intensive…right? Waste of money.”

- On subsidies and industrial policy: “Like a plant – in the very beginning when it’s a seed then you need to take care of it. But when it grows and becomes mature, then it can stand on its own and be competitive.”

- On an alternative to a centralised electricity grid: “I use the term ‘prosumerism’. Production, consumption and storage all in one, right? You do not require a very capital intensive power grid.…And also, this is consumer sovereignty – when you have your own system, you have a say and then…you are not totally reliant on the power grid.”

- On western suspicion: “Why did China suddenly become number one in zero-carbon renewables? It’s simply because the United States and Europe used anti-dumping subsidies and section 301 investigations in 2010. Then the Chinese competitive products, solar panels, were not able to go to the world market, so we thought we should…install everything inside of China and immediately China became number one in the world. Now you see the United States and Europe again say ‘no, it’s [a question of] supply chain security’. Right? This is really self-conflicting. On one hand they say ‘climate security’, on the other they say their ‘own security’.”

- On phasing out fossil fuels: “We want to have everything competitive enough to phase out fossil fuels, through the market process. Not command and control.”

- On abating fossil fuels: “I think that abated fossil fuels is a false statement. Because abated is not compatible, they have no competitiveness. When you abate it, it is more expensive. You think the consumers are silly? They will simply vote for competitive[ly priced] electricity.”

- On the future of fossil fuels: “Fossil fuels are fossils. They are a thing of the past.”

- On the ‘global stocktake’ negotiations: “[We talk about] responsibility sharing, carbon emissions reduction. But everybody will say ‘No, I will not [accept] any limits. You want to limit me, I want to do more.’ This is human psychology, right?”

- On the challenges of power market reform: “Only the monopoly people will [call for] ‘reform’, and through reform they gain more power, they gain more monopoly. The prosumerism system will destroy such monopolies.”

- On the urgency of ‘global boiling’: “Global warming is not global warming, it’s global boiling…Renewables are good for welfare, for wellbeing, for growing the economy, for a better environment. It’s for everybody and for the future. Fossil fuels are not for the future.”

Carbon Brief: If you don’t mind, I’d like to jump straight in. I read a lot about your work on defining the concept of an ecological civilisation, which is a concept that’s not very well understood outside China. In your previous work, you’ve described it as realising harmony between humans and nature in contrast to industrial civilisation. Could you give an overview of what an ecological civilisation is and how this concept has evolved?

Pan Jiahua: Well, from [the beginning of] human civilisation, from primitive agrarian society, human beings have relied somewhat completely on nature. The ability to live more comfortably was very limited and then, with technological innovation and the industrial revolution, we have entered the new era: the industrial stage. A sort of industrial civilisation.

Under industrial civilisation, we have an ethical principle, which is utilitarian. Measurement of happiness in human beings – we would like to be happy – and how to measure happiness? Then the British philosophers, they invented the idea of utilitarianism, which means that, once you have some sort of self-interest, self-achievement or self-realisation, then you are happy. And then happy, you need some sort of measurement. That is utilitarianism, everything is useful, everything brings you benefits, then you would be happier, right? This is utilitarian. And then the measurement in economic terminology, that is utility right? Everything has a utility and then that brings happiness to human beings. So that is utilitarianism, and then when there is no utility, then there is nothing to bring you happiness.

So this is the philosophy, the ethical foundation or ethical principle. And let’s put it another way: because of this ethical principle, that means that everybody tries to optimise his own utility. At the same time, when he maximises his own utility, he tries to provide services to other people and then the social welfare, social wellbeing in total is further improved, right? So this is the whole idea of the industrial revolution and industrialisation, that everybody would benefit.

But now, because human beings, for their own benefit – they ignored the benefit of nature. The welfare of nature. We expose nature, we deplete our natural resources, you know? And then nature is depleted and nature is destroyed, damaged, lost. And then we found that: “Oh my god, this is not sustainable.” We need to change back our principle, and not be utilitarian. We need to have something in harmony with nature, right?

Now, when we talk about security, right? Under an industrial utilitarian principle, security just [means] your own security – like the United States, like Donald Trump saying “America first”. The others, they are nobody, just America first. Others are secondary or tertiary or not important at all, only the United States is the most important. Right? Let’s get a slogan ‘America First’, so the others are not important and now it is the same. They talk about national security, their own security. The others, they don’t care. Like Russia’s own security. The others’ security is not on their agenda, right? So this is utilitarianism, this is self-interest. [Under the concept of ecological civilisation], security is not only for one but for all, for everybody, for man and nature.

CB: And does this include energy security?

PJH: Of course, energy security is one of many securities. So we need to understand security through a new mentality. This mentality has security for all. All the securities are important and should be treated equally, not that one security is superior to the others, all securities are important, should be treated equally, right? So this is harmony between man and nature. That means that not only in the United States, Russia, China, other developing countries – they should be treated equally. Your security, Russian security, Chinese security, all the securities should be treated at a similar level, as equally important. So this is a harmonious society, a harmonious world, harmonious human beings. Otherwise just your own security, the others’ security, they are not secure, and then how can they be guaranteed?

So this is the logic, and then, human beings are part of society, we are part of [the community of life on] Earth. Human beings are all one race. We have so many other species. Other species should also be treated equally. Their security, the plants, the animals and all the other forms of life. They should be treated equally, their security, not only human beings’ security, the security of nature, security of better diversity. So, this is all the securities, man and nature in harmony, living in harmony with nature. This is the principle. This principle is different from utilitarianism. That means on Earth we all are one community, an Earth community, a life community, we share our own planet, we share our future, not only one nation, one race, but everybody – not only [the] current generation, but future generations as well. So this is the basic idea that [if we can achieve] harmony with nature [and] harmony among our nations, then we can go long into the future. Otherwise, there’s conflicts among our nations, conflicts among culture, and then conflicts between man and nature. And then we will not have a future.

CB: You’ve actually teed up my next question really well. Given these hopes for harmony between different countries and harmony between man and nature, do you see the seeds of harmony at COP28?

PJH: I think that COP is the only thing that [has lasted] over 30 years. In 1990, when the United Nations created the intergovernmental negotiation committee, which resulted in the UNFCCC – this was agreed in 1992, and then in 1994 it came into force. This is the only one that lasts so long. And we have different views, different arguments, different interests but, all in all, we’ve come a long way, and now we come together and we agreed the Paris targets – in 1990 nobody would believe that [was possible]. “Oh no, global warming, that’s not my business, that’s something the rich guys should do, not us poor guys.” Right? And then at Copenhagen, when the 2C target was included in the Copenhagen Accord, that was no success at all.

And then, only five or six years later in 2015, we successfully completed the Paris Agreement. Not only 2C but 1.5C as well. And now step by step we come to a consensus. 1.5C should be the target and all our efforts should be focused on complying with 1.5C, and that’s the target. I think that’s why, in the UK for COP26 in Glasgow, [we had] 1.5C and then last year, at COP27, 1.5C was reiterated and reaffirmed, and this year [2023] I think that we should have no dissenting voices, right? So this is a great achievement and that means that all human beings can reach a consensus and can go further and further continuously. In the past, we would take a step forward and then go backward. And now at the climate conferences, we always go forward and make progress all the time. So this is really great.

But now I do have a different view. That is the global stocktake. I think that this is necessary, but [within the] global stocktake there are quite a few that are on a set track – [will they] derail or progress?

One is the “loss-and-damage fund”. Some people say that, okay, the climate morale requires the most vulnerable nations to be compensated for climate damages and climate losses. When on the first sight, it is reasonable, it is based on climate morale because they are not at any fault [for climate change] and they are suffering, so they should be compensated. I have a different view. Losses and damages should be compensated, but not in a way that we divert our energy and resources for [the sake of] compensation. We should use all our energy, resources, spirits – everything – for the zero-carbon transition. Because if you divert the limited resources for compensating losses and damages, then the zero-carbon transition would be delayed. And if you delay such a transition, there will be more and more losses and damages. I call this the climate paradox. The paradox of climate and morale.

CB: So is it a battle between short-term and long-term thinking?

PJH: No, it’s not short-term and long-term. You know, the mentality is not right. The mentality is that the focus should be zero-carbon transition. Because if you spend your time, resources, energy, negotiating the losses and damages fund – who suffers and who should pay and how the resources should be allocated – this is a waste of resources and a waste of time. Instead, we should focus our attention on zero-carbon transformation. Everything should be zero-carbon. All the people, all the countries, all the parties, all the resources: zero-carbon. And then, in the future, we would minimise our losses and damages. Otherwise, we will divert limited resources and then we will not be able to concentrate our efforts on zero-carbon transformation. So this is the mentality. I think that [the purpose of the] loss and damages [should] not be for compensation but for zero-carbon transition, zero-carbon transformation, zero carbon development.

Now if we see zero-carbon development, it is high quality. For instance, solar energy. Instead of compensation for losses and damages, you install solar panels and then you have energy. That is well-being, that is income, that is ability to develop, instead of some sort of imaginary losses and damages. Right?

CB: A critic might say, firstly countries are pledging to triple global renewables – so there is still focus on mitigation – but they might also say that countries that are seeing their infrastructure destroyed, for example through conflict, have the opportunity to develop new low-carbon infrastructure.

PJH: This is wrong. For one thing, tripling renewable energy is not enough. Why are we only tripling? Why not more and more, the more the better. Because look at China – [we] doubled and doubled and doubled [our renewable energy] all the time. This year we doubled installed capacity over the last year. Why shouldn’t we do more than just tripling? Insufficient, not enough, we should do more and more and more and more, not only tripling, it is not enough.

And the second thing: when you talk about replacing energy infrastructure. Renewables would not require a huge amount of investment in infrastructure. Fossil fuels, coal electricity generation – the investment is very capital intensive. It would require investment of a huge amount of money for construction of the thermal power plants, it would require a huge amount of investment into the power grid and distribution. Right? Waste of money.

If you go to zero-carbon solar panels on top of your roof, you have your electricity. And then when it’s intermittent, you see [we have] power batteries, which are so cheap. You should go to China to have a look at power batteries – 20 years ago, who would have imagined that electric vehicles would be competitive. Even three years ago nobody [would have thought so]. And now you see, [they are] so competitive.

CB: That’s so true, in my Beijing apartment, we didn’t have solar panels, but we did have EV charging points.

PJH: Right? So that means the infrastructure, everything is under your own control, you will not be reliant on capitalists. So that is the difference, right? Infrastructure. That’s why I say the “loss-and-damages fund” does nothing. Just zero-carbon transition, zero-carbon energy, zero-carbon development, zero-carbon welfare, zero-carbon well-being.

CB: To take China as an example, do you think that there’s more public consciousness around zero-carbon development? EVs makes sense because they were subsidised until recently –

PJH: They’re not subsidised any more. But you’re right, in the past it was. Everything, at the very beginning, was. Just like how when new babies are born, you should take care of them. That’s true for everything new. That’s natural, like a plant – in the very beginning when it’s a seed then you need to take care of it. But when it grows and becomes mature, then it can stand on its own and be competitive.

CB: So then, from the consumer’s point of view, are people interested in solar panels on their rooftops, recycling, things like that?

I think that this [consumer-based approach] is comprehensive and is inclusive. Everybody can contribute, to zero-carbon, to plastics, to energy, right? If you reuse materials, then you will reduce emissions. You would delay the depletion of fossil fuels. Right? So this is one of the approaches. All approaches combined leads to consensus, which is a Chinese value.

Renewables are competitive, electrical vehicles are competitive and batteries have huge potential, and everybody has high expectations that these batteries would become more and more competitive, and then every household, every school can be an independent unit. I call it “prosumerism”. Production of solar and [wind] turbines fuels generation of electricity, that’s production right? And consumption is kitchen utensils, heat pumps, air conditioning, light, everything – consumption. And then you have your storage – power batteries, right? Because of the intermittency of solar, the challenges can be resolved through power battery storage.

So I use the term “prosumerism”. Production, consumption and storage all in one, right? You do not require a very capital intensive power grid. That’s very impressive. And also, this is consumer sovereignty – when you have your own system, you have a say and then…you are not totally reliant on the power grid. If [the grid operators] say something is wrong, then you have no control, if they increase the price, then you have to accept it, you have no argument, everything is under their control. With prosumerism, everything is under your own control. I call it consumer sovereignty.

So why should developing countries spend money and waste money on the power grid? Just [adopt] an independent prosumerist system.

CB: I think the EU and the US now recognise they need to catch up with China’s solar industry, and we see them recognising the benefits of nurturing their “baby” industries –

PJH: Let me tell you, the EU and the United States, they always say one thing and do another, they’re very contradictory. Why did China suddenly become number one in zero-carbon renewables? It’s simply because the United States and Europe used anti-dumping subsidies and section 301 investigations in 2010. Then the Chinese competitive products, solar panels, were not able to go to the world market, so we thought we should do everything ourselves – then suddenly we should install everything inside of China and immediately China became number one in the world. Now you see the United States and Europe again say “no, it’s [a question of] supply chain security”. Right? This is really self-conflicting. On one hand they say “climate security”, on the other they say their “own security”. They don’t care about others, they don’t care about the climate. Because Chinese products are the most competitive in the world. If they are competitive, then everybody gains the lowest cost for installation of solar and wind.

CB: That’s very valid from a consumer point of view. I think everyone recognises that China is growing its renewable capacity at such a high rate, but can it sustain that indefinitely? Or will renewable energy eventually plateau? And at what point will it plateau?

PJH: I think that this is a good question. You know, for everything we have a process of very, very slow progress and then, suddenly, we have acceleration and we go to maturity. Once you get to maturity, you do not [need as much support], because, [like] human beings…once you are big enough, you do not require too much to eat, you do not require more food, right?

It’s the same, when zero-carbon energy is sufficient to meet your demand, that is enough. You do not need to produce more for nothing, for wasting, right? So that answers your question, that is when we have sufficient capacity, then there’s no need to produce more for China. But we do have [to have] such capacity, [because] we need renewables. We do have to have new technologies, right? It’s progress for China.

Now I think that we are developing very fast, we want to have everything competitive enough to phase out fossil fuels, through the market process. Not command and control. Use market forces to phase out fossil fuels because now, you see solar electricity, wind electricity, it’s only a fraction of coal-fired electricity, that’s still competitive. And now the intermittency challenge is resolved through storage, because what we need is energy services. We do not require carbon dioxide. Carbon dioxide is nothing.

CB: To clarify, you’re not talking about phasing out unabated fossil fuels, you’re talking about phasing out all fossil fuels?

PJH: I think that abated fossil fuels is a false statement. Because abated is not compatible, they have no competitiveness. When you abate it, it is more expensive. You think the consumers are silly? They will simply vote for competitive[ly priced] electricity. Right? So, I think that abated fossil fuels is a false statement. It does not stand. You know what I mean?

It is really a silly statement. I’ll give you an example – gasoline automobiles. Nowadays in China, you see the young people, who cares to buy [gasoline vehicles]? You have no market at all, nobody cares, nobody buys. Purely electric vehicles – that’s the market. Gasoline vehicles, no matter if they are ‘abated’ or ‘unabated’ – nobody cares. This is one illustrative example. So, the [idea of] abated fossil fuels really is nonsense. Nonsense.

CB: You mean that both the idea of unabated and abated fossil fuels are nonsense?

PJH: Both. Zero-carbon renewables are so competitive. They simply bring more employment, more revenue, better health and wellbeing. Right? And they give zero-carbon emissions. There are multiple wins.

CB: We’ve seen reports of particularly local governments building more coal capacity, perhaps to boost local economic growth. What do you think it would take –

PJH: You are right. In all societies, different people and different groups have different interests. For fossil fuels, in the past they were so powerful. They want to keep their power, they want to keep their influence, they want to keep their monopoly. It’s understandable. I don’t care at all – “okay, you do it”. But the next day, you guys realised it was wrong.

So I don’t care at all, [even though] so many people say in China local governments and state power companies are investing a huge amount in coal power. Never mind. They will be phased out automatically through the market. As I said, it is not command and control [that will drive the energy transition]. It’s market forces. It’s market power. Believe in market power.

CB: I heard someone make the argument that, as China tried to control the impact that the Covid-19 outbreak had on the economy, that coal interest groups may have lost some of their power and ‘new energy’ interest groups may have gained some power. Would you agree?

PJH: Well, we really don’t need to worry about this. The coal and fossil fuels industries are very powerful – state-owned and state-dominated. Very powerful. But I think “Okay, you are powerful. But, the sooner solar is [widely adopted], everybody can do it themselves, then we do not have to rely on them. We can let them be.” No matter how powerful they are today, I have no confidence that they will continue to hold a monopoly in the future, like the automobile sector. You know, in China automobile companies were state-owned companies, and so powerful in the past.

Now the evidence shows that fossil fuels are fossils. They are a thing of the past, they have no future. That’s why I think the global stocktake at COP28, the direction is wrong. We say “Oh the emissions reduction gap.” The gap is nothing.

CB: So what language do you expect to see out of the global stocktake?

PJH: The current language is wrong. [We talk about] responsibility sharing, carbon emissions reduction. But everybody will say “No, I will not [accept] any limits. You want to limit me, I want to do more.” This is human psychology, right? And so you say “No limits, you just do what you can.”

Zero-carbon renewable energy will bring employment, growth of the economy, wellbeing and a better environment. One example is electric vehicles: 100 kilometres (km) of drive, in China’s case, requires 12 kilowatt-hours (kWh) of electricity. 1 kWh of electricity, if you use solar together with power storage, would cost four, or at most five, US cents. Only five cents. That means that, less than one dollar – maybe 60 cents – will give you 100km distance, right? Using gasoline costs 10 times more. Consumers have the choice, it’s as simple as that.

If everybody knows that, who would say “Oh I want more fossil fuels, I want more emissions”? Emissions [would be] nothing, nobody [would need to] care about emissions. So I think that we should go in the right direction. Renewables, zero-carbon, that’s the right direction. Renewables, power batteries, electric vehicles, heat pumps. All of these are [good] for development, for quality of growth, for quality of living. That is the right direction, instead of [focusing on] “limit, limit, reduction, reduction”. Psychologically, nobody would accept limits. So that’s the logic – for growth, for the environment, for better wellbeing, that’s the logic.

CB: Will this be accelerated by expected reforms to the power spot market?

PJH: The power spot market, that’s also what the monopoly people will say. Right? And then if we [adopt the] prosumerism system, there’s no need to reform, right? We have millions and billions of [sources for] prosumerism. One household is a prosumerist unit. The market has nothing to do with the individual prosumerist system. Right?

So only the monopoly people will [call for] “reform”, and through reform they gain more power, they gain more monopoly. The prosumerism system will destroy such monopolies. I have my own system, I consume the electricity I generate, I can have everything stored in my own battery and I drive my electric vehicle. I have an independent, self-sufficient system. With monopolies – like the oil companies – the price is so volatile, because they want it to be volatile, so they can monopolise more and they can control the price. Now with electric vehicles, the oil companies are not able to control the drivers. Reform has nothing to do with it.

CB: Moving towards a zero-carbon society?

PJH: Exactly, that’s why [we are advocating for] the prosumerism system…we are going to do it inside China and then we’re going to introduce it to the world. We see a zero-carbon energy prosumerism system as a solution to a carbon neutral world. And then, in the prosumerist system, all the oil companies, all the fossil fuels – they are nobody, they are nothing. Consumers, households, they won’t care [about the fate of these companies]. That’s the solution, instead of price reform – that’s really the wrong direction. I am very confident that we have a solution, that’s the zero-carbon prosumerism system.

CB: Thank you professor. And, for my last question: do you talk to your friends and family about climate change?

PJH: Of course! Global warming is not global warming, it’s global boiling. We cannot stand, our biodiversity cannot stand, our future will not be able to sustain. So we have a solution – that’s renewables, and just renewables. Renewables are good for welfare, for wellbeing, for growing the economy, for a better environment. It’s for everybody and for the future. Fossil fuels are not for the future.

The post The Carbon Brief Interview: Prof Pan Jiahua appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Pacific nations would be paid only thousands for deep sea mining, while mining companies set to make billions, new research reveals

SYDNEY/FIJI, Thursday 26 February 2026 — New independent research commissioned by Greenpeace International has revealed that Pacific Island states would receive mere thousands of dollars in payment from deep sea mining per year, placing the region as one of the most affected but worst-off beneficiaries in the world.

The research by legal professor Dr Harvey Mpoto Bombaka and development economist Dr Ben Tippet reveals that mechanisms proposed by the International Seabed Authority (ISA) for sharing any future revenues from deep sea mining would leave developing nations with meagre, token payments. Pacific Island nations would receive only USD $46,000 per year in the short term, then USD $241,000 per year in the medium term, averaging out to barely USD $382,000 per year for 28 years – an entire annual income for a nation that is less than some individual CEOs’ salaries. Mining companies would rake in over USD $13.5 billion per year, taking up to 98% of the revenues.

The analysis shows that under a scenario where six deep sea mining sites begin operating in the early 2030s, the revenues that states would actually receive are extraordinarily small. This is in contrast to the clear mandate of the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS), which requires mining to be carried out for the benefit of humankind as a whole.[1] The real beneficiaries, the research shows, would be, yet again, a handful of corporations in the Global North.

Head of Pacific at Greenpeace Australia Pacific Shiva Gounden, said:

“What the Pacific is being promised amounts to little more than scraps. The people of the Pacific would sacrifice the most and receive the least if deep sea mining goes ahead. We are being asked to trade in our spiritual and cultural connection to our oceans, and risk our livelihoods and food sources, for almost nothing in return.

“The deep sea mining industry has manipulated the Pacific and has lied to our people for too long, promising prosperity and jobs that simply do not exist. The wealthy CEOs and deep sea mining companies will pocket the cash while the people of the Pacific see no material benefits. The Pacific will not benefit from deep sea mining, and our sacrifice is too big to allow it to go ahead. The Pacific Ocean is not a commodity, and it is not for sale.”

Using proposals submitted by the ISA’s Finance Committee between 2022 and 2025, the returns to states barely register in national accounts. After administrative costs, institutional expenses, and compensation funds are deducted, little, if anything, remains to distribute [3].

Author Dr Harvey Mpoto Bombaka of the Centro Universitário de Brasília said:

“What’s described as global benefit-sharing based on equity and intergenerational justice increasingly looks like a framework for managing scarcity that would deliver almost no real benefits to anyone other than the deep sea mining industry. The structural limitations of the proposed mechanism would offer little more than symbolic returns to the rest of the world, particularly developing countries lacking technological and financial capacity.”

The ISA will meet in March for its first session of the year. Currently, 40 countries back a moratorium or precautionary pause on deep sea mining.

Gounden added: “The deep sea belongs to all humankind, and our people take great pride in being the custodians of our Pacific Ocean. Protecting this with everything we have is not only fair and responsible but what we see as our ancestral duty. The only equitable path is to leave the minerals where they are and stop deep sea mining before it starts.

“The decision on the future of the ocean must be a process that centres the rights and voices of Pacific communities as the traditional custodians. Clearly, deep sea mining will not benefit the Pacific, and the only sensible way forward is a moratorium.”

—ENDS—

Notes

[1] A key condition for governments to permit deep sea mining to start in the international seabed is that it ‘be carried out for the benefit of mankind as a whole’, particularly developing nations, according to international law (Article 136-140, 148, 150, and 160(2)(g), the UN Convention on the Law of the Sea).

For more information or to arrange an interview, please contact Kimberley Bernard on +61407 581 404 or kbernard@greenpeace.org

Climate Change

North Carolina Regulators Nix $1.2 Billion Federal Proposal to Dredge Wilmington Harbor

U.S. Army Corps of Engineers failed to explain how it would mitigate environmental harms, including PFAS contamination.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers can’t dredge 28 miles of the Wilmington Harbor as planned, after North Carolina environmental regulators determined the billion-dollar proposal would be inconsistent with the state’s coastal management policies.

North Carolina Regulators Nix $1.2 Billion Federal Proposal to Dredge Wilmington Harbor

Climate Change

Australia’s renewable energy opportunity

Australia has some of the largest areas of high volume, consistent solar and wind energy anywhere in the world. It is a natural advantage that many countries in our region and across Europe will envy as they ramp up their efforts to reduce carbon pollution.

Australia has an amazing opportunity to utilise this abundance of reliable energy not only to transform our own energy systems but also that of our neighbours – if we get the policy settings right.

We are, in fact, already seeing the benefits of renewable energy flowing into our electricity grids. With all the inflation pressures on our bank accounts it looks like electricity pricing may be one cost that could be turning a corner – largely thanks to cheap solar and wind energy.

Renewables are Bringing Down the Cost of Producing Electricity

Here at Greenpeace, while we think there are some important questions to ask about renewable energy, it is clear that solar and wind are certainly the cheapest energy options available.

In contrast, coal, oil and gas are not only big on pollution, they are also proving costlier as they struggle to cope with the changing nature of our electricity systems. Plus, fossil fuels are much more exposed to international price fluctuations – as we all experienced when our electricity bills rapidly rose following the Russian invasion of Ukraine.

Wouldn’t it be great if we instead had energy independence, sourced from an infinite supply of clean energy?

Solar and wind (backed by batteries) can do just that and the reality is that they are already out-competing the old guard of gas and coal simply because they are quicker and cheaper to deploy. Which is good news for electricity prices!

Although whether energy retailers are passing on those savings to customers is another question. Short answer: no, they’re not – but it is a bit complex.

Why are my electricity bills still high?

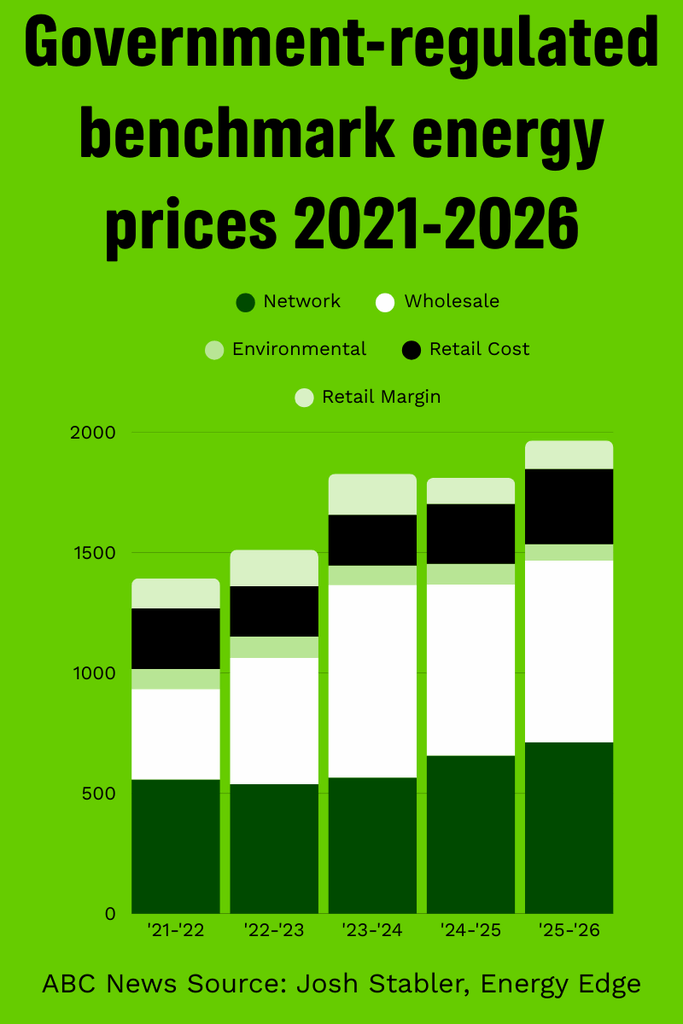

There are a number of elements that make up the final amount we see on our bills. The graph below shows the breakdown of energy costs covered by our bills.

You will see roughly a third (36.2% in 2025-26) of the cost goes to maintenance and build out of the electricity grid. This includes the transmission lines needed to connect to new renewable energy sites and to connect states so they can better share their energy resources. The ‘network’ costs have been increasing but so have other components of our bill, most notably the ‘wholesale’ cost of producing electricity.

Thankfully, the cost of producing the electricity is now starting to go down (thanks to renewables and batteries), but they are coming off record highs thanks to the exorbitant cost of gas and the unreliability of coal power stations that are old and no longer fit for purpose.

During high demand times (eg, when we all get home from work on a hot day and turn on the air conditioning) spot prices can quickly jump. Add to that a couple of coal power plants breaking down (as they increasingly do), and expensive gas fired power use spikes in the system. This can quickly cancel out any of the cost savings solar power may have created during the day when prices can actually go negative.

The good news is that this is exactly the problem batteries can solve. Batteries are great at soaking up the surplus supply of solar during the middle of the day, which creates a more efficient system, and then rapidly pumping out that power during the evening peak at a cheaper rate than gas.

How much have costs come down?

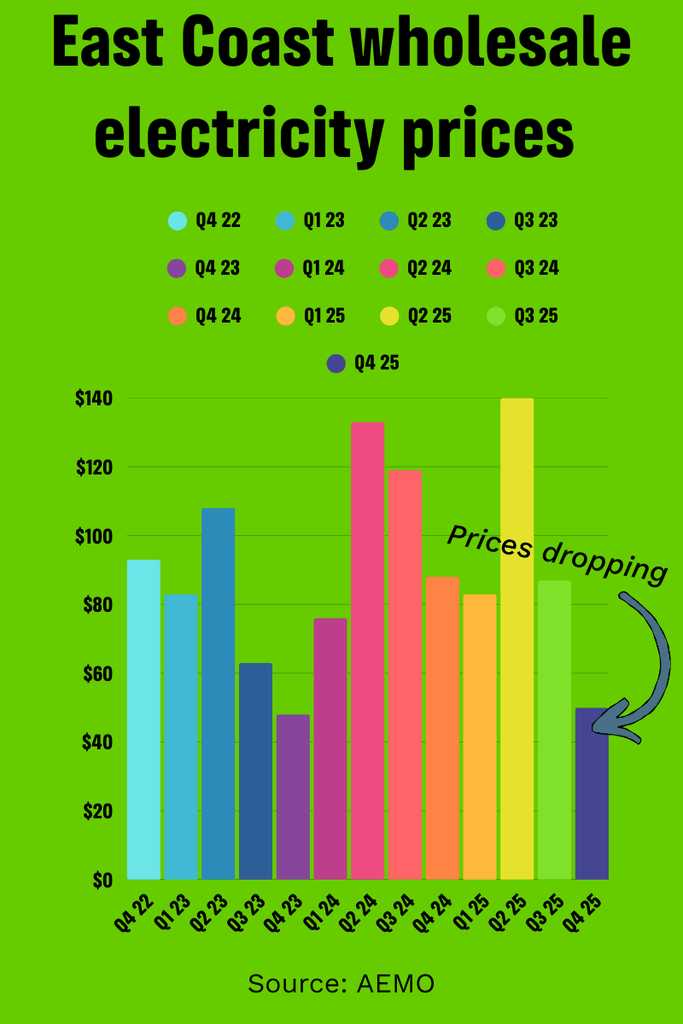

According to the Australian energy regulator (AEMO), wholesale electricity prices across the east coast have dropped by 44% when comparing prices in quarter 4 of 2025 to the same period in 2024.

AEMO directly attributes the change to the significant growth in wind (up 29%), solar (up 15%), and batteries (3,796 MW of new battery capacity added). This influx of cheap renewable energy has seen a corresponding decrease in the use of polluting fossil fuels to power the grid. Coal fired power dropped by 4.6% and gas fired power fell by a staggering 27%.

The same trend can be seen in the world’s largest standalone grid in WA where renewable energy and storage supplied a record 52.4% of the grid’s energy across the final 3 months of 2025. That is an impressive result given there is no interstate connection to borrow energy from and there is no hydroelectric power in the system.

As a result, WA has seen a 13% drop in wholesale electricity prices thanks to a 5.8% reduction in coal fired power and a 16.4% reduction in gas fired power.

Australian Households Lead the Way on Solar and Batteries

Despite all the attempts to discredit clean energy by Trump and other conservative politicians, Aussie households have long known the value of renewable energy. In fact, Australia now holds the title for the highest rate of solar energy per capita in the world.

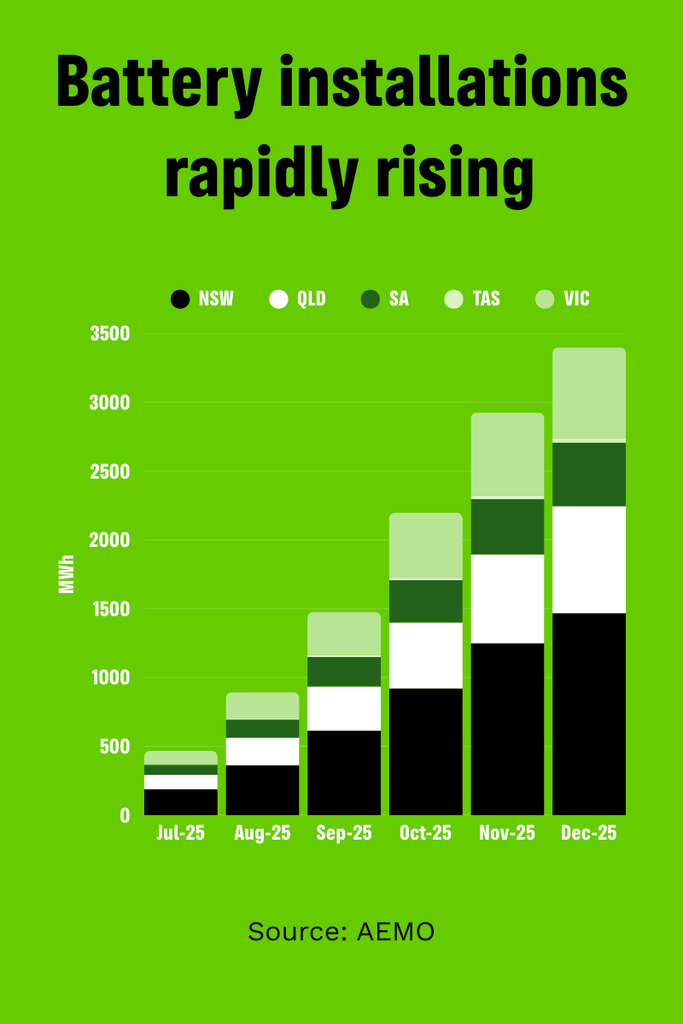

This is now being followed by the rapid takeup of household batteries with the Clean Energy Regulator being overwhelmed with interest in the Cheaper Home Batteries Program. They now expect to receive “around 175,000 valid battery applications corresponding to a total usable capacity of 3.9 GWh by the end of 2025.”’

All these extra batteries storing the surplus solar energy across our neighbourhoods during the day is not only creating drastic bill reductions for those households who are installing them, it is helping the whole grid. Which eventually will help everyone’s electricity bills.

If Australia as a whole follows the lead of suburban families by switching to cheap solar (plus wind) backed-up by batteries, it has an unparalleled opportunity to build its economy on the back of unlimited, local, clean energy harnessed from the sun and wind.

Powering our Future Economy

If there was ever something Australia has a natural advantage in, its sun and wind. But given the growing demand for electricity from data centres and the electrification of heavy industry, we are going to need more than just rooftop solar panels.

That’s where Australia has the potential, more than almost any other country, to become a renewable energy powerhouse and punch above our weight in the fight against climate change. See for example the unique opportunity to enter into the production and export of green iron.

While there is still quite a way to go before our electricity is fully sourced from solar and wind, we are well on the way. The clean energy charge is gathering pace – and our communities, oceans, wildlife and bank balances will be the better for it.

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits