Russia’s new climate plan justifies the use of natural gas as a “transition fuel” by referencing the controversial loophole that it pushed to have included in the COP28 pledge on shifting away from fossil fuels.

In a landmark agreement at the Dubai climate summit two years, governments agreed to call on each other to work on “transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems” as one of eight global efforts to fight climate change.

The hard-won agreement followed years of campaigning by climate activists and pro-climate action governments, and was hailed as “the beginning of the end” for the fossil fuel era by UN climate chief Simon Stiell.

But in a concession to some countries that were led by Russia – the world’s second-biggest gas producer, the COP28 agreement included a paragraph recognising that “transitional fuels can play a role in facilitating the energy transition while ensuring energy security”.

After it was agreed, Antigua and Barbuda negotiator Diann Black-Layne called it a “dangerous loophole” because natural gas is a fossil fuel “we need to transition away from”.

This year, all the signatories of the 2015 Paris Agreement are due to submit their emissions reduction targets up to 2035, and must say how their targets have “been informed by” the COP28 agreement.

Gas as “transition fuel”

Russia’s new climate plan says it is compatible with paragraph 28 of the COP28 agreement – which includes the language on transitioning away from fossil fuels – because Russia “continues to contribute to the global effort to reduce greenhouse gas emissions through national efforts to the greatest possible extent”.

It adds that the transition should be “based on independence and freedom of choice, the technological neutrality in designing the composition of energy mix and implementing climate policies in the energy sector”.

It then cites the COP28 language around transitional fuels to say Russia “uses natural gas as a transition fuel on the way towards a low-carbon economy” and gas “is the most environmentally friendly type of fuel among the types of conventional heat generation”.

While burning gas for power releases less emissions directly than burning coal, whether or not it emits less overall depends mostly on how much gas leaks as it is transported from where it is produced to where it is consumed, energy experts say.

Andreas Sieber, associate director of policy and campaigns at renewable energy advocacy group 350.org, said Russia was “wilfully misreading the global stocktake”.

“Rebranding methane-heavy, flare-ridden gas as a ‘transition fuel’ is spin, not science [which] props up a regime whose political economy runs on petro-rents and aggression,” Sieber told Climate Home News, adding “any credible transition runs on renewables and efficiency, not on Russia’s gas”.

Russian climate envoy Ruslan Edelgeriev told a UN climate summit last week the country’s commitment to reaching net zero by 2060 was firm and it “has moved from strategy to practical implementation”.

Russia is not the only government to play down the COP28 language on transitioning away from fossil fuels. Shortly after COP28, the Saudi energy minister said the agreement in Dubai was just an “a la carte menu” from which governments could choose.

And several African countries including Nigeria have set out plans to boost the use of fossil gas as a “transition fuel” in their updated Nationally Determined Contributions (NDCs).

“Unambitious” target

Russia’s plan aims to reduce emissions to 33%-35% below their 1990 levels by 2035. This adds to existing targets to cut emissions by 30% on 1990 levels by 2030 and reach net zero – when the country emits no more than it absorbs – by 2060.

Russia’s emissions dropped by a quarter after the Soviet Union collapsed in the 1990s, making percentage reductions on 1990 levels much more achievable. US President Donald Trump noted this in a recent UN speech, saying “Russia was given an old standard that was easy to meet – 1990 standard”.

Climate Action Tracker (CAT), a nonprofit which assesses governments’ climate plans and policies, said Russia’s new 2035 target “does not increase ambition beyond business as usual” because Russia’s current policies already put it on course to cut emissions 35% by 2035.

CAT said that is at odds with a Paris Agreement principle that targets should reflect the “highest possible ambition”. “Russia’s 2035 target not only fails to reflect highest ambition, but does not increase ambition at all”, CAT said in an analysis on its website.

Russia says the target is in line with the Paris Agreement’s goal to hold a temperature increase to 2C and pursue efforts to limit it to 1.5C. CAT said, however, that it was only compatible with warming of 4C or more.

Under its climate plan, Russia says it will cut overall emissions through gas, nuclear, hydropower, renewables, carbon capture and storage and hydrogen. It will also aim to reduce the emissions which come from producing coal and oil, by capturing and selling gas rather than burning it as a waste product and by detecting and fixing pipeline leaks.

CAT also accused Russia of taking too much credit in its carbon accounting for the emissions absorbed by its huge forests. UN guidelines say countries should only take credit for forests which they actively manage, giving governments discretion to decide which land falls into this category.

Russia claims it manages nearly two-thirds of its vast forests, a percentage CAT said was “inflated”. Other heavily forested nations such as Guyana – which claims to be “carbon negative” – have been criticised by climate campaigners for similarly large assumptions about how much forest they manage.

The post Russia justifies fossil gas use by citing contentious COP28 loophole appeared first on Climate Home News.

Russia justifies fossil gas use by citing contentious COP28 loophole

Climate Change

DeBriefed 6 February 2026: US secret climate panel ‘unlawful’ | China’s clean energy boon | Can humans reverse nature loss?

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s DeBriefed.

An essential guide to the week’s key developments relating to climate change.

This week

Secrets and layoffs

UNLAWFUL PANEL: A federal judge ruled that the US energy department “violated the law when secretary Chris Wright handpicked five researchers who rejected the scientific consensus on climate change to work in secret on a sweeping government report on global warming”, reported the New York Times. The newspaper explained that a 1972 law “does not allow agencies to recruit or rely on secret groups for the purposes of policymaking”. A Carbon Brief factcheck found more than 100 false or misleading claims in the report.

DARKNESS DESCENDS: The Washington Post reportedly sent layoff notices to “at least 14” of its climate journalists, as part of a wider move from the newspaper’s billionaire owner, Jeff Bezos, to eliminate 300 jobs at the publication, claimed Climate Colored Goggles. After the layoffs, the newspaper will have five journalists left on its award-winning climate desk, according to the substack run by a former climate reporter at the Los Angeles Times. It comes after CBS News laid off most of its climate team in October, it added.

WIND UNBLOCKED: Elsewhere, a separate federal ruling said that a wind project off the coast of New York state can continue, which now means that “all five offshore wind projects halted by the Trump administration in December can resume construction”, said Reuters. Bloomberg added that “Ørsted said it has spent $7bn on the development, which is 45% complete”.

Around the world

- CHANGING TIDES: The EU is “mulling a new strategy” in climate diplomacy after struggling to gather support for “faster, more ambitious action to cut planet-heating emissions” at last year’s UN climate summit COP30, reported Reuters.

- FINANCE ‘CUT’: The UK government is planning to cut climate finance by more than a fifth, from £11.6bn over the past five years to £9bn in the next five, according to the Guardian.

- BIG PLANS: India’s 2026 budget included a new $2.2bn funding push for carbon capture technologies, reported Carbon Brief. The budget also outlined support for renewables and the mining and processing of critical minerals.

- MOROCCO FLOODS: More than 140,000 people have been evacuated in Morocco as “heavy rainfall and water releases from overfilled dams led to flooding”, reported the Associated Press.

- CASHFLOW: “Flawed” economic models used by governments and financial bodies “ignor[e] shocks from extreme weather and climate tipping points”, posing the risk of a “global financial crash”, according to a Carbon Tracker report covered by the Guardian.

- HEATING UP: The International Olympic Committee is discussing options to hold future winter games earlier in the year “because of the effects of warmer temperatures”, said the Associated Press.

54%

The increase in new solar capacity installed in Africa over 2024-25 – the continent’s fastest growth on record, according to a Global Solar Council report covered by Bloomberg.

Latest climate research

- Arctic warming significantly postpones the retreat of the Afro-Asian summer monsoon, worsening autumn rainfall | Environmental Research Letters

- “Positive” images of heatwaves reduce the impact of messages about extreme heat, according to a survey of 4,000 US adults | Environmental Communication

- Greenland’s “peripheral” glaciers are projected to lose nearly one-fifth of their total area and almost one-third of their total volume by 2100 under a low-emissions scenario | The Cryosphere

(For more, see Carbon Brief’s in-depth daily summaries of the top climate news stories on Monday, Tuesday, Wednesday, Thursday and Friday.)

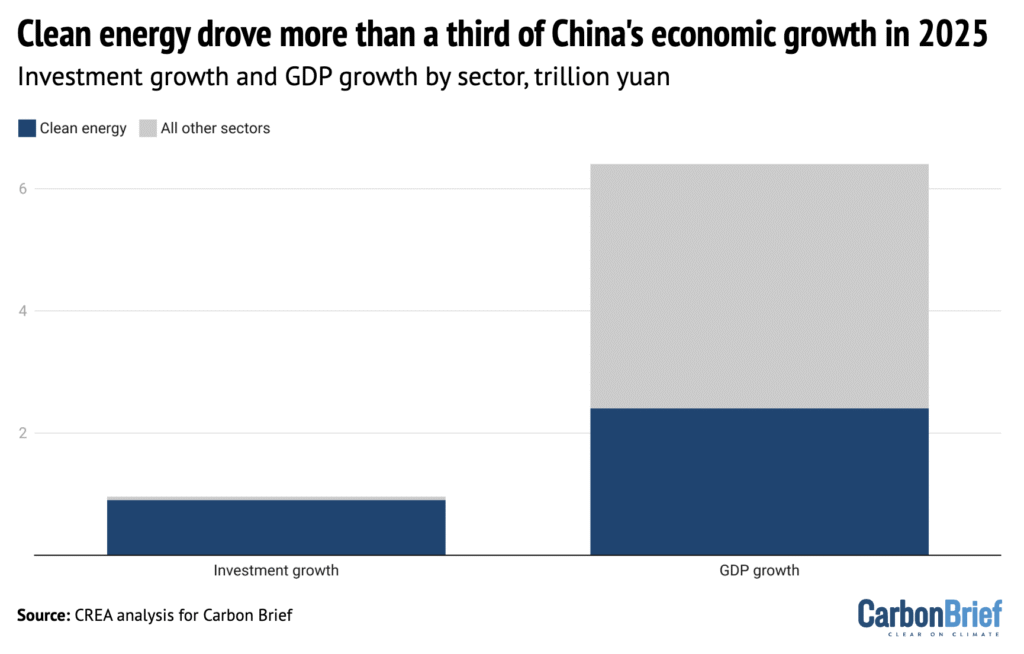

Captured

Solar power, electric vehicles and other clean-energy technologies drove more than a third of the growth in China’s economy in 2025 – and more than 90% of the rise in investment, according to new analysis for Carbon Brief (shown in blue above). Clean-energy sectors contributed a record 15.4tn yuan ($2.1tn) in 2025, some 11.4% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP) – comparable to the economies of Brazil or Canada, the analysis said.

Spotlight

Can humans reverse nature decline?

This week, Carbon Brief travelled to a UN event in Manchester, UK to speak to biodiversity scientists about the chances of reversing nature loss.

Officials from more than 150 countries arrived in Manchester this week to approve a new UN report on how nature underpins economic prosperity.

The meeting comes just four years before nations are due to meet a global target to halt and reverse biodiversity loss, agreed in 2022 under the landmark “Kunming-Montreal Global Biodiversity Framework” (GBF).

At the sidelines of the meeting, Carbon Brief spoke to a range of scientists about humanity’s chances of meeting the 2030 goal. Their answers have been edited for length and clarity.

Dr David Obura, ecologist and chair of Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES)

We can’t halt and reverse the decline of every ecosystem. But we can try to “bend the curve” or halt and reverse the drivers of decline. That’s the economic drivers, the indirect drivers and the values shifts we need to have. What the GBF aspires to do, in terms of halting and reversing biodiversity loss, we can put in place the enabling drivers for that by 2030, but we won’t be able to do it fast enough at this point to halt [the loss] of all ecosystems.

Dr Luthando Dziba, executive secretary of IPBES

Countries are due to report on progress by the end of February this year on their national strategies to the Convention on Biological Diversity [CBD]. Once we get that, coupled with a process that is ongoing within the CBD, which is called the global stocktake, I think that’s going to give insights on progress as to whether this is possible to achieve by 2030…Are we on the right trajectory? I think we are and hopefully we will continue to move towards the final destination of having halted biodiversity loss, but also of living in harmony with nature.

Prof Laura Pereira, scientist at the Global Change Institute at Wits University, South Africa

At the global level, I think it’s very unlikely that we’re going to achieve the overall goal of halting biodiversity loss by 2030. That being said, I think we will make substantial inroads towards achieving our longer term targets. There is a lot of hope, but we’ve also got to be very aware that we have not necessarily seen the transformative changes that are going to be needed to really reverse the impacts on biodiversity.

Dr David Cooper, chair of the UK’s Joint Nature Conservation Committee and former executive secretary of the Convention on Biological Diversity

It’s important to look at the GBF as a whole…I think it is possible to achieve those targets, or at least most of them, and to make substantial progress towards them. It is possible, still, to take action to put nature on a path to recovery. We’ll have to increasingly look at the drivers.

Prof Andrew Gonzalez, McGill University professor and co-chair of an IPBES biodiversity monitoring assessment

I think for many of the 23 targets across the GBF, it’s going to be challenging to hit those by 2030. I think we’re looking at a process that’s starting now in earnest as countries [implement steps and measure progress]…You have to align efforts for conserving nature, the economics of protecting nature [and] the social dimensions of that, and who benefits, whose rights are preserved and protected.

Neville Ash, director of the UN Environment Programme World Conservation Monitoring Centre

The ambitions in the 2030 targets are very high, so it’s going to be a stretch for many governments to make the actions necessary to achieve those targets, but even if we make all the actions in the next four years, it doesn’t mean we halt and reverse biodiversity loss by 2030. It means we put the action in place to enable that to happen in the future…The important thing at this stage is the urgent action to address the loss of biodiversity, with the result of that finding its way through by the ambition of 2050 of living in harmony with nature.

Prof Pam McElwee, Rutgers University professor and co-chair of an IPBES “nexus assessment” report

If you look at all of the available evidence, it’s pretty clear that we’re going to keep experiencing biodiversity decline. I mean, it’s fairly similar to the 1.5C climate target. We are not going to meet that either. But that doesn’t mean that you slow down the ambition…even though you recognise that we probably won’t meet that specific timebound target, that’s all the more reason to continue to do what we’re doing and, in fact, accelerate action.

Watch, read, listen

OIL IMPACTS: Gas flaring has risen in the Niger Delta since oil and gas major Shell sold its assets in the Nigerian “oil hub”, a Climate Home News investigation found.

LOW SNOW: The Washington Post explored how “climate change is making the Winter Olympics harder to host”.

CULTURE WARS: A Media Confidential podcast examined when climate coverage in the UK became “part of the culture wars”.

Coming up

- 2-8 February: 12th session of the Intergovernmental Science-Policy Platform on Biodiversity and Ecosystem Services (IPBES), Manchester, UK

- 8 February: Japanese general election

- 8 February: Portugal presidential election

- 11 February: Barbados general election

- 11-12 February: UN climate chief Simon Stiell due to speak in Istanbul, Turkey

Pick of the jobs

- UK Met Office, senior climate science communicator | Salary: £43,081-£46,728. Location: Exeter, UK

- Canadian Red Cross, programme officer, Indigenous operations – disaster risk reduction and climate change adaptation | Salary: $56,520-$60,053. Location: Manitoba, Canada

- Aldersgate Group, policy officer | Salary: £33,949-£39,253. Location: London (hybrid)

DeBriefed is edited by Daisy Dunne. Please send any tips or feedback to debriefed@carbonbrief.org.

This is an online version of Carbon Brief’s weekly DeBriefed email newsletter. Subscribe for free here.

The post DeBriefed 6 February 2026: US secret climate panel ‘unlawful’ | China’s clean energy boon | Can humans reverse nature loss? appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

China Briefing 5 February 2026: Clean energy’s share of economy | Record renewables | Thawing relations with UK

Welcome to Carbon Brief’s China Briefing.

China Briefing handpicks and explains the most important climate and energy stories from China over the past fortnight. Subscribe for free here.

Key developments

Solar and wind eclipsed coal

‘FIRST TIME IN HISTORY’: China’s total power capacity reached 3,890 gigawatts (GW) in 2025, according to a National Energy Administration (NEA) data release covered by industry news outlet International Energy Net. Of this, it said, solar capacity rose 35% to 1,200GW and wind capacity was up 23% to 640GW, while thermal capacity – which is mostly coal – grew 6% to just over 1,500GW. This marks the “first time in history” that wind and solar capacity has outranked coal capacity in China’s power mix, reported the state-run newspaper China Daily. China’s grid-related energy storage capacity exceeded 213GW in 2025, said state news agency Xinhua. Meanwhile, clean-energy industries “drove more than 90%” of investment growth and more than half of GDP growth last year, said the Guardian in its coverage of new analysis for Carbon Brief. (See more in the spotlight below.)

DAWN FOR SOLAR: Solar power capacity alone may outpace coal in 2026, according to projections by the China Electricity Council (CEC), reported business news outlet 21st Century Business Herald. It added that non-fossil sources could account for 63% of the power mix this year, with coal falling to 31%. Separately, the China Renewable Energy Society said that annual wind-power additions could grow by between 600-980GW over the next five years, with annual additions of 120GW expected until 2028, said industry news outlet China Energy Net. China Energy Net also published the full CEC report.

STATE MEDIA VOICE: Xinhua published several energy- and climate-related articles in a series on the 15th five-year plan. One said that becoming a low-carbon energy “powerhouse” will support decarbonisation efforts, strengthen industrial innovation and improve China’s “global competitive edge and standing”. Another stated that coal consumption is “expected” to peak around 2027, with continued “growth” in the power and chemicals sector, while oil has already peaked. A third noted that distributed energy systems better matched the “characteristics of renewable energy” than centralised ones, but warned against “blind” expansion and insufficient supporting infrastructure. Others in the series discussed biodiversity and environmental protection and recycling of clean-energy technology. Meanwhile, the communist party-affiliated People’s Daily said that oil will continue to play a “vital role” in China, even after demand peaks.

Starmer and Xi endorsed clean-energy cooperation

CLIMATE PARTNERSHIP: UK prime minister Keir Starmer and Chinese president Xi Jinping pledged in Beijing to deepen cooperation on “green energy”, reported finance news outlet Caixin. They also agreed to establish a “China-UK high-level climate and nature partnership”, said China Daily. Xi told Starmer that the two countries should “carry out joint research and industrial transformation” in new energy and low-carbon technologies, according to Xinhua. It also cited Xi as saying China “hopes” the UK will provide a “fair” business environment for Chinese companies.

-

Sign up to Carbon Brief’s free “China Briefing” email newsletter. All you need to know about the latest developments relating to China and climate change. Sent to your inbox every Thursday.

OCTOPUS OVERSEAS: During the visit, UK power-trading company Octopus Energy and Chinese energy services firm PCG Power announced they would be starting a new joint venture in China, named Bitong Energy, reported industry news outlet PV Magazine. The move “marks a notable direct entry” of a foreign company into China’s “tightly regulated electricity market”, said Caixin.

PUSH AND PULL: UK policymakers also visited Chinese clean-energy technology manufacturer Envision in Shanghai, reported finance news outlet Yicai. It quoted UK business secretary Peter Kyle emphasising that partnering with companies “like Envision” on sustainability is a “really important part of our future”, particularly in terms of job creation in the UK. Trade minister Chris Bryant told Radio Scotland Breakfast that the government will decide on Chinese wind turbine manufacturer Mingyang’s plans for a Scotland factory “soon”. Researchers at the thinktank Oxford Institute for Energy Studies wrote in a guest post for Carbon Brief that greater Chinese competition in Europe’s wind market could “help spur competition in Europe”, if localisation rules and “other guardrails” are applied.

More China news

- LIFE SUPPORT: China will update its coal capacity payment mechanism, which will raise thresholds for coal-fired power plants and expand to cover gas-fired power and pumped and new-energy storage, reported current affairs outlet China News.

- FRONTIER TECH: The world’s “largest compressed-air power storage plant” has begun operating in China, said Bloomberg.

- PARTNERSHIP A ‘MISTAKE’: The EU launched a “foreign subsidies” probe into Chinese wind turbine company Goldwind, said the Hong Kong-based South China Morning Post. EU climate chief Wopke Hoekstra said the bloc must resist China’s pull in clean technologies, according to Bloomberg.

- TRADE SPAT: The World Trade Organization “backed a complaint by China” that the US Inflation Reduction Act “discriminated against” Chinese cleantech exports, said Reuters.

- NEW RULES: China has set “new regulations” for the Waliguan Baseline Observatory, which provides “key scientific references for the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change”, said the People’s Daily.

Captured

New or reactivated proposals for coal-fired power plants in China totalled 161GW in 2025, according to a new report covered by Carbon Brief.

Spotlight

Clean energy drove China’s economic growth in 2025

New analysis for Carbon Brief finds that clean-energy sectors contributed the equivalent of $2.1tn to China’s economy last year, making it a key driver of growth. However, headwinds in 2026 could restrict growth going forward – especially for the solar sector.

Below is an excerpt from the article, which can be read in full on Carbon Brief’s website.

Solar power, electric vehicles (EVs) and other clean-energy technologies drove more than a third of the growth in China’s economy in 2025 – and more than 90% of the rise in investment.

Clean-energy sectors contributed a record 15.4tn yuan ($2.1tn) in 2025, some 11.4% of China’s gross domestic product (GDP)

Analysis shows that China’s clean-energy sectors nearly doubled in real value between 2022-25 and – if they were a country – would now be the 8th-largest economy in the world.

These investments in clean-energy manufacturing represent a large bet on the energy transition in China and overseas, creating an incentive for the government and enterprises to keep the boom going.

However, there is uncertainty about what will happen this year and beyond, particularly due to a new pricing system, worsening industrial “overcapacity” and trade tensions.

Outperforming the wider economy

China’s clean-energy economy continues to grow far more quickly than the wider economy, making an outsized contribution to annual growth.

Without these sectors, China’s GDP would have expanded by 3.5% in 2025 instead of the reported 5.0%, missing the target of “around 5%” growth by a wide margin.

Clean energy made a crucial contribution during a challenging year, when promoting economic growth was the foremost aim for policymakers.

In 2024, EVs and solar had been the largest growth drivers. In 2025, it was EVs and batteries, which delivered 44% of the economic impact and more than half of the growth of the clean-energy industries.

The next largest subsector was clean-power generation, transmission and storage, which made up 40% of the contribution to GDP and 30% of the growth in 2025.

Within the electricity sector, the largest drivers were growth in investment in wind and solar power generation capacity, along with growth in power output from solar and wind, followed by the exports of solar-power equipment and materials.

But investment in solar-panel supply chains, a major growth driver in 2022-23, continued to fall for the second year, as the government made efforts to rein in overcapacity and “irrational” price competition.

Headwinds for solar

Ongoing investment of hundreds of billions of dollars represents a gigantic bet on a continuing global energy transition.

However, developments next year and beyond are unclear, particularly for solar. A new pricing system for renewable power is creating uncertainty, while central government targets have been set far below current rates of clean-electricity additions.

Investment in solar-power generation and solar manufacturing declined in the second half of the year.

The reduction in the prices of clean-energy technology has been so dramatic that when the prices for GDP statistics are updated, the sectors’ contribution to real GDP – adjusted for inflation or, in this case deflation – will be revised down.

Nevertheless, the key economic role of the industry creates a strong motivation to keep the clean-energy boom going. A slowdown in the domestic market could also undermine efforts to stem overcapacity and inflame trade tensions by increasing pressure on exports to absorb supply.

Local governments and state-owned enterprises will also influence the outlook for the sector.

Provincial governments have a lot of leeway in implementing the new electricity markets and contracting systems for renewable power generation. The new five-year plans, to be published this year, will, therefore, be of major importance.

This spotlight was written for Carbon Brief by Lauri Myllyvirta, lead analyst at Centre for Research on Energy and Clean Air (CREA), and Belinda Schaepe, China policy analyst at CREA. CREA China analysts Qi Qin and Chengcheng Qiu contributed research.

Watch, read, listen

PROVINCE INFLUENCE: The Institute for Global Decarbonization Progress, a Beijing-based thinktank, published a report examining the climate-related statements in provincial recommendations for the 15th five-year plan.

‘PIVOT’?: The Outrage + Optimism podcast spoke with the University of Bath’s Dr Yixian Sun about whether China sees itself as a climate leader and what its role in climate negotiations could be going forward.

COOKING FOR CLEAN-TECH: Caixin covered rising demand for China’s “gutter oil” as companies “scramble” to decarbonise.

DON’T GO IT ALONE: China News broadcast the Chinese foreign ministry’s response to the withdrawal of the US from the Paris Agreement, with spokeswoman Mao Ning saying “no country can remain unaffected” by climate change.

$6.8tn

The current size of China’s green-finance economy, including loans, bonds and equity, according to Dr Ma Jun, the Institute of Finance and Sustainability’s president,in a report launch event attended by Carbon Brief. Dr Ma added that “green loans” make up 16% of all loans in China, with some areas seeing them take a 34% share.

New science

- China’s official emissions inventories have overestimated its hydrofluorocarbon emissions by an average of 117m tonnes of carbon dioxide equivalent (mtCO2e) every year since 2017 | Nature Geoscience

- “Intensified forest management efforts” in China from 2010 onwards have been linked to an acceleration in carbon absorption by plants and soils | Communications Earth and Environment

Recently published on WeChat

China Briefing is written by Anika Patel and edited by Simon Evans. Please send tips and feedback to china@carbonbrief.org

The post China Briefing 5 February 2026: Clean energy’s share of economy | Record renewables | Thawing relations with UK appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Climate Change

Congress rescues aid budget from Trump’s “evisceration” but climate misses out

Under pressure from Congress, President Donald Trump quietly signed into law a funding package that provides billions of dollars more in foreign assistance spending than he had originally wanted to for the fiscal year between October 2025 and September 2026.

The legislation allocates $50 billion, $9 billion less than the level agreed the previous year under President Biden but $19 billion more than Trump proposed, restoring health and humanitarian aid spending to near pre-Trump levels.

Democratic Senator Patty Murray, vice-chair of the committee on appropriations, said that “while including some programmatic funding cuts, the bill rejects the Trump administration’s evisceration of US foreign assistance programmes”.

But, with climate a divisive issue in the US, spending on dedicated climate programmes was largely absent. Clarence Edwards, executive director of E3G’s US office, told Climate Home News that “the era of large US government investment in climate policy is over, at least for the foreseeable future”.

The package ruled out any support for the Climate Investment Funds’ Clean Technology Fund, which supports low-carbon technologies in developing countries and had received $150 million from the US in the previous fiscal year.

The US also made no pledge to the Africa Development Fund (ADF) – a mechanism run by the African Development Bank that provides grants and low-interest loans to the poorest African nations. A government spokesperson told Reuters that decision reflected concerns that “like too many other institutions, the ADF has adopted a disproportionate focus on climate change, gender, and social issues”.

GEF spared from cuts

Trump did, however, agree to Congress’s request to make $150 million – more than last year – available for the Global Environment Facility (GEF), which tackles environmental issues like biodiversity loss, land degradation and climate change.

Edwards said that GEF funding “survived due to Congressional pushback and a refocus on non-climate priorities like biodiversity, plastics and ocean ecosystems, per US Treasury guidance”.

Congress also pressured Trump into giving $54 million to the Rome-based International Fund for Agricultural Development. Its goals include helping small-scale farmers adapt to climate change and reduce emissions.

Without any pressure from Congress, Trump approved tens of millions of dollars each for multilateral development banks in Asia, Africa and Europe and just over a billion dollars for the World Bank’s International Development Association, which funds development projects in the world’s poorest countries.

As most of these banks have climate programmes and goals, much of this money is likely to be spent on climate action. The largest lender, the World Bank, aims to devote 45% of its finance to climate programmes, although, as Climate Home News has reported, its definition of climate spending is considered too loose by some analysts.

The bill also earmarks $830 million – nearly triple what Trump originally wanted – for the Millennium Challenge Corporation, a George W. Bush-era institution that has increasingly backed climate-focussed projects like transmission lines to bring clean hydropower to cities in Nepal.

No funding boost for DFC

While Congress largely increased spending, it rejected Trump’s call for nearly $4 billion for the Development Finance Corporation (DFC), granting just under $1 billion instead – similar to previous years.

Under Biden, there had been a push to get the DFC to support clean energy projects. But the Trump administration ended DFC’s support for projects like South Africa’s clean energy transition.

At a recent board meeting, the DFC’s board – now dominated by Trump administration officials – approved US financial support for Chevron Mediterranean Limited, the developers of an Israeli gas field.

Kate DeAngelis, deputy director at Friends of the Earth US told Climate Home News it was good for the climate that Trump had not been able to boost the DFC’s budget. “DFC seems set up to focus mainly on the dirtiest deals without any focus on development,” she said.

US Congressional elections in November could lead to Democrats retaking control of one or both houses of Congress. Edwards said that “Democratic gains might restore funding [in the next fiscal year], while Republican holds would likely extend cuts”.

But he warned that “budgetary pressures and a murky economic environment don’t hold promise of increases in US funding for foreign assistance and climate programs, regardless of which party controls Congress”.

The post Congress rescues aid budget from Trump’s “evisceration” but climate misses out appeared first on Climate Home News.

Congress rescues aid budget from Trump’s “evisceration” but climate misses out

-

Greenhouse Gases6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change6 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Renewable Energy2 years ago

GAF Energy Completes Construction of Second Manufacturing Facility