A confused – and, at times, contradictory – story has emerged about precisely which countries and negotiating blocs were opposed to a much-discussed “roadmap” deal at COP30 on “transitioning away from fossil fuels”.

Carbon Brief has obtained a leaked copy of the 84-strong “informal list” of countries that, as a group, were characterised across multiple media reports as “blocking” the roadmap’s inclusion in the final “mutirão” deal across the second week of negotiations at the UN climate summit in Belém.

During the fraught closing hours of the summit, Carbon Brief understands that the Brazilian presidency told negotiators in a closed meeting that there was no prospect of reaching consensus on the roadmap’s inclusion, because there were “80 for and 80 against”.

However, Carbon Brief’s analysis of the list – which was drawn up informally by the presidency – shows that it contains a variety of contradictions and likely errors.

Among the issues identified by Carbon Brief is the fact that 14 countries are listed as both supporting and opposing the idea of including a fossil-fuel roadmap in the COP30 outcome.

In addition, the list of those said to have opposed a roadmap includes all 42 of the members of a negotiating group present in Belém – the least-developed countries (LDCs) – that has explicitly told Carbon Brief it did not oppose the idea.

Moreover, one particularly notable entry on the list, Turkey – which is co-president of COP31 – tells Carbon Brief that its inclusion is “wrong”.

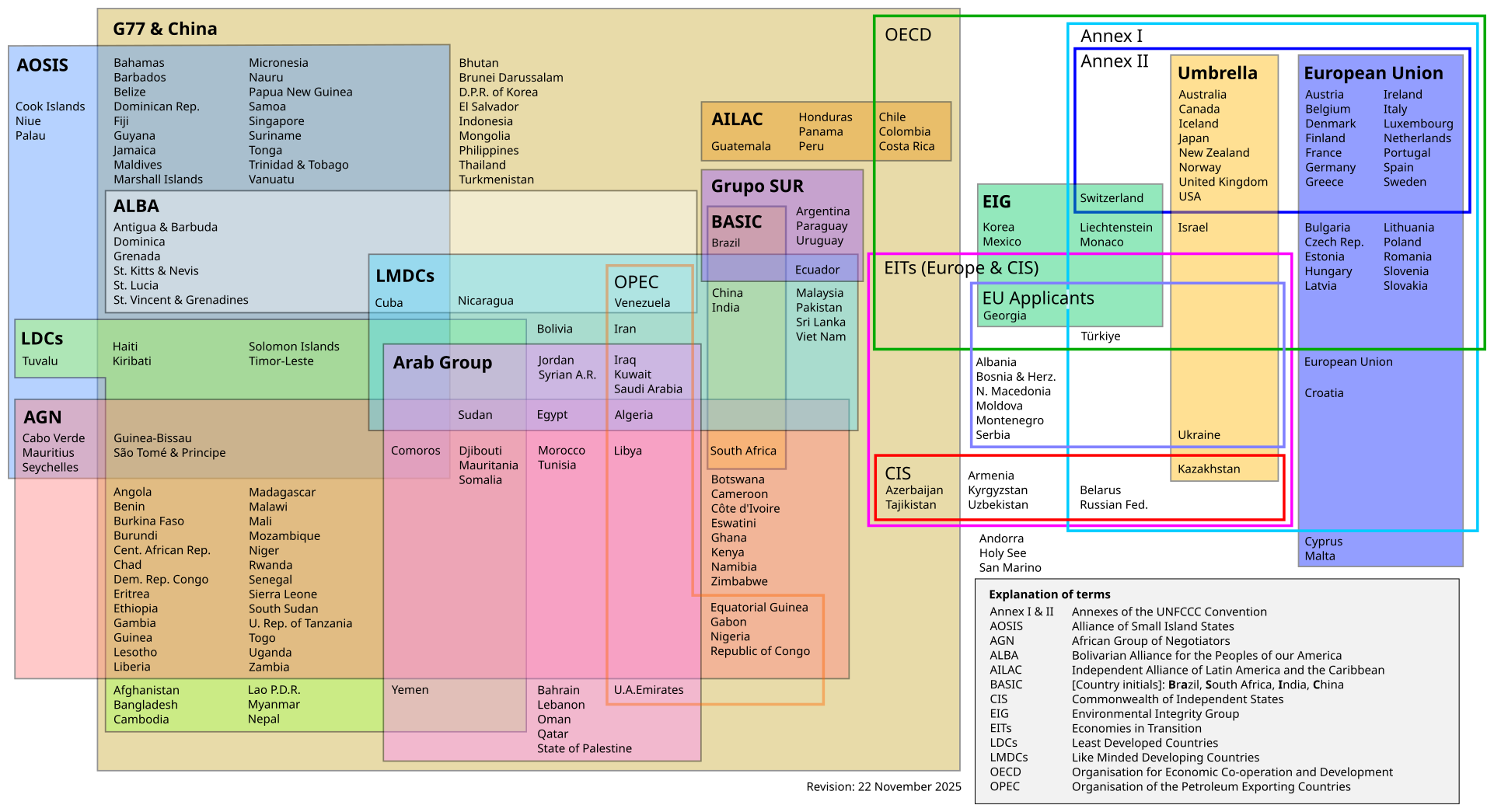

Negotiating blocs

COP28, held in Dubai in 2023, had finalised the first “global stocktake”, which called on all countries to contribute to global efforts, including a “transition away from fossil fuels”.

Since then, negotiations on how to take this forward have faltered, including at COP29 in Baku, Azerbaijan, where countries were unable to agree to include this fossil-fuel transition as part of existing or new processes under the UN climate regime.

Ahead of the start of COP30, Brazilian president Luiz Inácio Lula da Silva made a surprise call for “roadmaps” on fossil-fuel transition and deforestation.

While this idea was not on the official agenda for COP30, it had been under development for months ahead of the summit – and it became a key point of discussion in Belém.

Ultimately, however, it did not become part of the formal COP30 outcome, with the Brazilian presidency instead launching a process to draw up roadmaps under its own initiative.

This is because the COP makes decisions by consensus. The COP30 presidency insisted that there was no prospect of consensus being reached on a fossil-fuel roadmap, telling closed-door negotiations that there were “80 for and 80 against”.

The list of countries supporting a roadmap as part of the COP30 outcome was obtained by Carbon Brief during the talks. Until now, however, the list of those opposed to the idea had not been revealed.

Carbon Brief understands that this second list was drawn up informally by the Brazilian presidency after a meeting attended by representatives of around 50 nations. It was then filled out to the final total of 84 countries, based on membership of negotiating alliances.

The bulk of the list of countries opposing a roadmap – some 39 nations – is made up of two negotiating blocs that opposed the proposal for divergent reasons (see below). Some countries within these blocs also held different positions on why – or even whether – they opposed the roadmap being included in the COP30 deal.

These blocs are the 22-strong Arab group – chaired in Belém by Saudi Arabia – and the 25 members of the “like-minded developing countries” (LMDCs), chaired by India.

For decades within the UN climate negotiations, countries have sat within at least one negotiating bloc rather than act in isolation. At COP30, the UN says there were 16 “active groups”. (Since its invasion of Ukraine, Russia has not sat within any group.)

The inclusion on the “informal list” (shown in full below) of both the LMDCs and Arab group is accurate, as confirmed by the reporting of the International Institute for Sustainable Development’s Earth Negotiations Bulletin (ENB), which is the only organisation authorised to summarise what has happened in UN negotiations that are otherwise closed to the media.

Throughout the fortnight of the talks, both the LMDCs and Arab group were consistent – at times together – in their resistance to proscriptive wording and commitments within any part of the COP30 deal around transitioning away from fossil fuels.

But the reasons provided were nuanced and varied and cannot be characterised as meaning both blocs simply did not wish to undertake the transition – in fact, all countries under the Paris Agreement had already agreed to this in Dubai two years ago at COP28.

However, further analysis by Carbon Brief of the list shows that it also – mistakenly – includes all of the members of the LDCs, bar Afghanistan and Myanmar, which were not present at the talks. In total, the LDCs represented 42 nations in Belém, ranging from Bangladesh and Benin through to Tuvalu and Tanzania.

Some of the LDC nations had publicly backed a fossil-fuel roadmap.

‘Not correct’

Manjeet Dhakal, lead adviser to the LDC chair, tells Carbon Brief that it is “not correct” that the LDCs, as a bloc, opposed a fossil-fuel roadmap during the COP30 negotiations.

He says that the group’s expectations, made public before COP, clearly identified transitioning away from fossil fuels as an “urgent action” to keep the Paris Agreement’s 1.5C goal “within reach”. He adds:

“The LDC group has never blocked a fossil-fuel roadmap. [In fact], a few LDCs, including Nepal, have supported the idea.”

Dhakal’s statement highlights a further confusing feature of the informal list – 14 countries appear on both of the lists of supporters and opposers. This is possible because many countries sit within two or more negotiating blocs at UN climate talks.

For example, Kiribati, Solomon Islands and Tuvalu are members of both the “alliance of small island states” (AOSIS) and the LDCs.

As is the case with the “informal list” of opposers, the list of supporters (which was obtained by Carbon Brief during the talks) is primarily made up of negotiating alliances.

Specifically, it includes AOSIS, the “environmental integrity group” (EIG), the “independent association of Latin America and the Caribbean” (AILAC) and the European Union (EU).

In alphabetical order, the 14 countries on both lists are: Bahrain; Bulgaria; Comoros; Cuba; Czech Republic; Guinea-Bissau; Haiti; Hungary; Kiribati; Nepal; Sierra Leone; Solomon Islands; Timor-Leste; and Tuvalu.

This obvious anomaly acts to highlight the mistaken inclusion of the LDCs on the informal list of opposers.

The list includes 37 of the 54 nations within the Africa group, which was chaired by Tanzania in Belém.

But this also appears to be a function of the mistaken inclusion of the LDCs in the list, many of which sit within both blocs.

Confusion

An overview of the talks published by the Guardian this week reported:

“Though [Brazil’s COP30 president André Corrêa do Lago] told the Guardian [on 19 November] that the divide over the [roadmap] issue could be bridged, [he] kept insisting 80 countries were against the plan, though these figures were never substantiated. One negotiator told the Guardian: ‘We don’t understand where that number comes from.’

“A clue came when Richard Muyungi, the Tanzanian climate envoy who chairs the African group, told a closed meeting that all its 54 members aligned with the 22-member Arab Group on the issue. But several African countries told the Guardian this was not true and that they supported the phaseout – and Tanzania has a deal with Saudi Arabia to exploit its gas reserves.”

Adding to the confusion, the Guardian also said two of the most powerful members of the LMDCs were not opposed to a roadmap, reporting: “China, having demurred on the issue, indicated it would not stand in the way [of a roadmap]; India also did not object.”

Writing for Climate Home News, ActionAid USA’s Brandon Wu said:

“Between rich country intransigence and undemocratic processes, it’s understandable – and justifiable – that many developing countries, including most of the Africa group, are uncomfortable with the fossil-fuel roadmap being pushed for at COP30. It doesn’t mean they are all ‘blockers’ or want the world to burn, and characterising them as such is irresponsible.

“The core package of just transition, public finance – including for adaptation and loss and damage – and phasing out fossil fuels and deforestation is exactly that: a package. The latter simply will not happen, politically or practically, without the former.”

Carbon Brief understands that Nigeria was a vocal opponent of the roadmap’s inclusion in the mutirão deal during the final hours of the closed-door negotiations, but that does not equate to it opposing a transition away from fossil fuels. This is substantiated by the ENB summary:

“During the…closing plenary…Nigeria stressed that the transition away from fossil fuels should be conducted in a nationally determined way, respecting [common, but differentiated responsibilities and respective capabilities].”

The “informal list” of opposers also includes three EU members – Bulgaria, the Czech Republic and Hungary.

The EU – led politically at the talks by climate commissioner Wopke Hoekstra, but formally chaired by Denmark – was reportedly at the heart of efforts to land a deal that explicitly included a “roadmap” for transitioning away from fossil fuels.

Carbon Brief understands that, as part of the “informal intelligence gathering” used to compile the list, pre-existing positions on climate actions by nations were factored in rather than only counting positions expressed at Belém. For example, Hungary and the Czech Republic were reported to have been among those resisting the last-minute “hard-fought deal” by the EU on its 2040 climate target and latest Paris Agreement climate pledge.

(Note that EU members Poland and Italy did not join the list of countries supporting a fossil-fuel roadmap at COP30.)

The remaining individual nations on the informal list either have economies that are heavily dependent on fossil-fuel production (for example, Russia and Brunei Darussalam), or are, like the US, currently led by right-leaning governments resistant to climate action (for example, Argentina).

Turkey is a notable inclusion on the list because it was agreed in Belém that it will host next year’s COP31 in Antalya, but with Australia leading the negotiation process. In contrast, Australia is on the 85-strong list of roadmap supporters.

However, a spokesperson for Turkey’s delegation in Belem has told Carbon Brief that it did not oppose the roadmap at COP30 and its inclusion on the list is “wrong”.

Media characterisations

Some media reporting of the roadmap “blockers” sought to identify the key proponents.

For example, the Sunday Times said “the ‘axis of obstruction’ – Saudi Arabia, Russia and China – blocked the Belém roadmap”.

Agence France-Presse highlighted the views of a French minister who said: “Who are the biggest blockers? We all know them. They are the oil-producing countries, of course. Russia, India, Saudi Arabia. But they are joined by many emerging countries.”

Reuters quoted Vanuatu’s climate minister alleging that “Saudi Arabia was one of those opposed”.

The Financial Times said “a final agreement [was] blocked again and again by countries led by Saudi Arabia and Russia”.

Bloomberg said the roadmap faced “stiff opposition from Arab states and Russia”.

Media coverage in India and China has pushed back at the widespread portrayals of what many other outlets had described as the “blockers” of a fossil-fuel roadmap.

The Indian Express reported:

“India said it was not opposed to the mention of a fossil-fuel phaseout plan in the package, but it must be ensured that countries are not called to adhere to a uniform pathway for it.”

Separately, speaking on behalf of the LMDCs during the closing plenary at COP30, India had said: “Adaptation is a priority. Our regime is not mitigation centric.”

China Daily, a state-run newspaper that often reflects the government’s official policy positions, published a comment article this week stating:

“Over 80 countries insisted that the final deal must include a concrete plan to act on the previous commitment to move beyond coal, oil, and natural gas adopted at COP28…But many delegates from the global south disagreed, citing concerns about likely sudden economic contraction and heightened social instability. The summit thus ended without any agreement on this roadmap.

“Now that the conference is over, and emotions are no longer running high, all parties should look objectively at the potential solution proposed by China, which some international media outlets wrongly painted as an opponent to the roadmap.

“Addressing an event on the sidelines of the summit, Xia Yingxian, deputy head of China’s delegation to COP30, said the narrative on transitioning away from fossil fuels would find greater acceptance if it were framed differently, focusing more on the adoption of renewable energy sources.”

Speaking to Carbon Brief at COP30, Dr Osama Faqeeha, Saudi Arabia’s deputy environment minister, refused to be drawn on whether a fossil-fuel roadmap was a red line for his nation, but said:

“I think the issue is the emissions, it’s not the fuel. And our position is that we have to cut emissions regardless.”

Neither the Arab group nor the LMDCs responded to Carbon Brief’s invitation to comment on their inclusion on the list.

The Brazilian COP30 presidency did not respond at the time of publication.

While the fossil-fuel roadmap was not part of the formal COP30 outcome, the Brazilian presidency announced in the closing plenary that it would take the idea forward under its own initiative, drawing on an international conference hosted in Colombia next year.

Corrêa do Lago told the closing plenary:

“We know some of you had greater ambitions for some of the issues at hand…As president Lula said at the opening of this COP, we need roadmaps so that humanity, in a just and planned manner, can overcome its dependence on fossil fuels, halt and reverse deforestation and mobilise resources for these purposes.

“I, as president of COP30, will therefore create two roadmaps, one on halting and reverting deforestation, another to transitioning away from fossil fuels in a just, orderly and equitable manner. They will be led by science and they will be inclusive with the spirit of the mutirão.

“We will convene high level dialogues, gathering key international organisations, governments from both producing and consuming countries, industry workers, scholars, civil society and will report back to the COP. We will also benefit from the first international conference for the phase-out of fossil fuels, scheduled to take place in April in Colombia.”

Fossil-fuel roadmap

‘Supporters’

Both ‘supporter’ and ‘opposer’

‘Opposers’

Additional reporting by Daisy Dunne.

The post Revealed: Leak casts doubt on COP30’s ‘informal list’ of fossil-fuel roadmap opponents appeared first on Carbon Brief.

Revealed: Leak casts doubt on COP30’s ‘informal list’ of fossil-fuel roadmap opponents

Climate Change

The Iran War Is Making the Case for Renewable Energy, Experts Argue

As Brent crude approaches $100 a barrel, clean energy advocates say the Hormuz crisis is the latest proof that fossil fuel dependence leaves consumers at the mercy of distant wars.

The war between the United States, Israel and Iran has triggered the largest disruption to global oil supplies in the history of the modern oil market, with Brent crude prices currently hovering around $100 a barrel, sending economic shockwaves across Persian Gulf states, Asian countries and the U.S. with no clear endgame in sight.

The Iran War Is Making the Case for Renewable Energy, Experts Argue

Climate Change

Attacks on Middle East Desalination Plants Highlight Risks of Near-Total Dependence on ‘Fossil Fuel Water’

Destroying the facilities is a violation of international law that could cause a humanitarian crisis in the most water-scare region on Earth. Powering the plants with electricity from fossil fuels poses additional long-term threats.

Recent attacks in the Middle East on desalination plants, facilities that remove salt from seawater, raise the potential for a humanitarian crisis if the region’s freshwater production facilities are subjected to more widespread destruction. The attacks also underscore the region’s heavy reliance on an energy-intensive method of producing drinking water that is powered almost entirely by fossil fuels.

Climate Change

There’s Something in the Air in South Portland, Maine

Emissions test results are in on the city’s 120 petroleum storage tanks. One activist scientist says they are high enough “to merit serious attention,” while a Citgo spokesman says the company is taking residents’ concerns seriously and working with state regulators.

SOUTH PORTLAND—It’s one of Maine’s most desirable locations—home to a vibrant and diverse community, nearby beaches, and close proximity to Portland’s downtown. But for years, residents in South Portland have wondered: With 120 massive petroleum storage tanks dotting the shore and knitted into some neighborhoods here, is the air safe to breathe?

-

Greenhouse Gases7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Climate Change7 months ago

Guest post: Why China is still building new coal – and when it might stop

-

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago

Greenhouse Gases2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Bill Discounting Climate Change in Florida’s Energy Policy Awaits DeSantis’ Approval

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Spanish-language misinformation on renewable energy spreads online, report shows

-

Climate Change2 years ago

Climate Change2 years ago嘉宾来稿:满足中国增长的用电需求 光伏加储能“比新建煤电更实惠”

-

Climate Change Videos2 years ago

The toxic gas flares fuelling Nigeria’s climate change – BBC News

-

Carbon Footprint2 years ago

Carbon Footprint2 years agoUS SEC’s Climate Disclosure Rules Spur Renewed Interest in Carbon Credits